Abstract

Introduction

Empathy is crucial to the fundamental aim and achievement of nursing and midwifery goals. Researchers agree on the positive role empathy plays in interpersonal relationships when providing healthcare. Models of good communication have been developed to assist nurses, midwives and doctors to improve their ability to communicate with patients. This study investigated the effect of a 2-day communication skills training (CST) on nursing and midwifery students’ empathy in a randomised controlled trial.

Methods

The two groups had a baseline data collection at the same time. The intervention group had a CST, followed by post-test on day 3. The control group had post-test on day 4 just before their CST. The empathy outcome was measured with Jefferson Scales of Empathy-Health Professions Student version. Both groups had a follow-up test at the same time 6 months after the CST.

Results

In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in the scores of empathy between the groups F(1, 171)=0.18, p=0.675. The intervention group had baseline T1 (M=109.8, SD=9.8, d=0.160), and post-test T2 (M=111.9, SD=9.0, d=0.201), whereas the control group had baseline T1 (M=107.9, SD=11.46, d=0.160), and post-test T2 (M=110.0, SD=11.0, d=0.201). Baseline data were collected on 15 June 2013.

Conclusions

This study has shown that empathy may not be enhanced within a short period after CST.

Keywords: empathy, nursing education, midwifery, randomised controlled trial, Ghana

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used nursing and midwifery students who were actively involved. The use of various methods like group discussions, roleplays, videos, short presentations and brainstorming sessions in the delivery of the communication skills training was a also a positive development, since such methods take care of individual differences.

There was allocation concealment to the researcher, research assistants and the participants.

The empathy measure used was Jefferson Scales of Empathy-Health Professions Student version has good construct validity and criterion-related validity which has been reported.

A limitation of this study is the generalisation of the results to other healthcare professionals. As a self-report outcome, results of this study cannot be generalised beyond the characteristics of this sample.

Confounding factors can also limit the generalisability of this study; the study could not control for interaction between the groups during the period of the study. This could lead to the problem of contamination between the groups (ie, those in the intervention group talking to those in the control group after their training session days).

Introduction

Empathy is crucial to the fundamental aim and achievement of nursing and midwifery goals.1 Within the nursing and midwifery field, such skills are considered indicative of best practice.2 It has also been stressed that empathy is a necessary factor in the provision of quality nursing care.3 Researchers agree on the positive role empathy plays in interpersonal relationships when providing healthcare.4 5

Models of good communication have been developed to assist nurses, midwives and doctors to improve their ability to communicate with patients.6–12 A health maintenance organisation (Kaiser Permanente in the USA) developed the Four Habits Model, which they have used for more than 20 years and is an effective programme for clinical communication.6 7 The model has been anchored into four habits: ‘invest in the beginning (Habit I), elicit patients’ perspective (Habit II), demonstrate empathy (Habit III), and invest in the end (Habit IV)’.6 7 The habits from this theory was the basis of the communication skills training (CST) that was developed and used for this study. The other theoretical model called the Person-Centred Nursing Framework (PCNF)13 was an essential component of the CST. Emphasis was made on PCNF necessary care processes of working with the patients beliefs and values, engagement, shared decision making, having sympathetic presence and providing holistic care.13

Objective

To investigate the effect of a 2-day CST on nursing and midwifery students’ (NMS) empathy in a randomised controlled trial.

Methodology

Design and sample

This study was a 2 (intervention condition, between) x 3 (time, repeated) design in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted at Tamale Nurses and Midwives College Ghana. The sample consisted of nursing students (n=181) and midwifery students (n=49).

Power analysis

The sample size of the participants was based on a power analysis. Relationship have been shown between training interventions and improved communication skills, measured with Roter Interaction Analysis System, with an effect size between medium and high.14 Fixing the effect size medium (d=0.25), using a two-tailed significance test (p=0.05), a sample size of 197 resulted in an acceptable power coefficient of 0.95.15 The sample size was computed using G*Power software.15 16

Informed consent

Informed consent was not written and participants were told that taking part in the CST and answering the questionnaires meant their consent and an agreement to any publication from it. Participants were informed of the objectives of the study but not in detail such that they would know that the study wants to determine their empathy level, but were also given opportunity to ask questions to enable them to decide to take part in this study. Participants were informed that they could refuse to take part in the research at any time without having to face any consequence.

Patient and public involvement

Participants in this study were NMS and patients were not involved. The students as well as their tutors were involved in the design of the CST guide.

Criteria of inclusion and exclusion

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in box 1.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Nursing and midwifery students (NMS) in their second year at Tamale Nursing and Midwifery College.

NMS whose ages were above 18 years.

NMS in Tamale Nursing and Midwifery College who were available for follow-up data collection after 6 months.

Exclusion criteria

NMS who were not studying at Tamale Nursing and Midwifery College.

NMS whose ages were below 18 years.

NMS in Tamale Nursing and Midwifery College who were not available for follow-up data collection after 6 months.

Randomisation

There was allocation concealment to the researcher, research assistants and the participants. The researcher (MA) and research assistants conducted this by allowing participants to pick numbers written on papers, which had been randomly shuffled in a box. NMS were separated before random assignment to ensure that both professions were approximately equally represented in the groups. Therefore, participants were randomly assigned to either intervention group or a control group.

Procedure

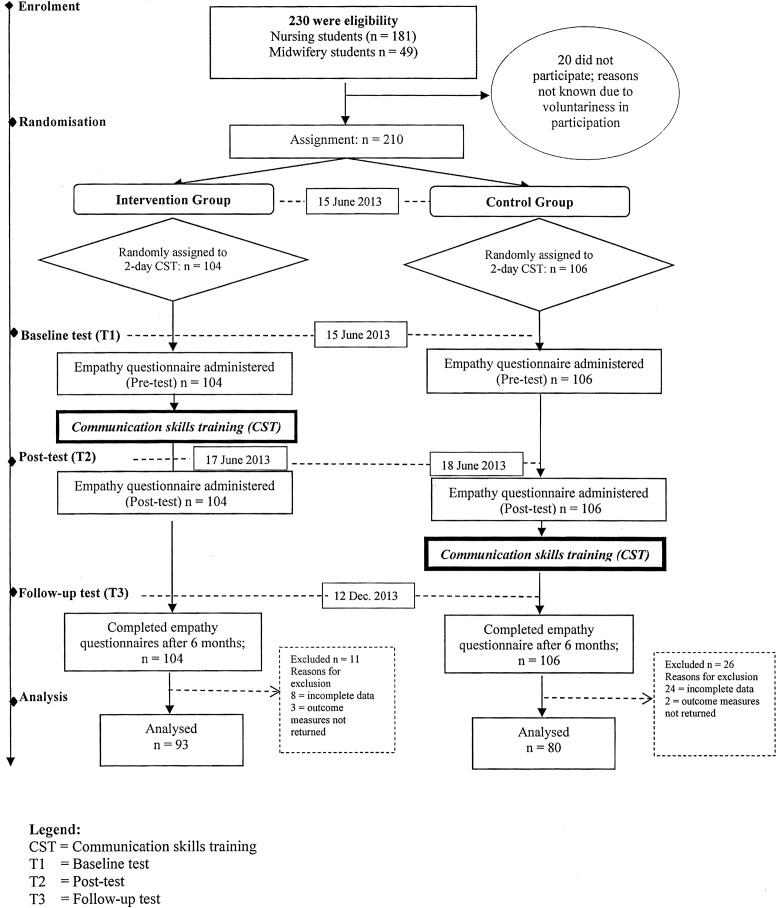

The two groups had a baseline data collection (T1) at the same time. The intervention group had a CST, followed by post-test (T2) on day 3. The control group had post-test (T2) on day 4 just before their CST. The CST for both groups were the same. The tutors were aware of the training and data collection for the intervention and control group; however, the intervention and control groups were not aware. The outcome was measured with Jefferson Scales of Empathy-Health Professions Student version (JSE HPS version).17 Both groups had a follow-up test (T3) at the same time 6 months after the CST (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing enrolment, randomisation, communication skills training and data collection.

Outcome measure

The outcome was empathy measured with JSE HPS version.4 JSE HPS version was in English. This questionnaire was administered in English. This is because the students are very fluent in English. They are taught in English from primary school because English is the official language in Ghana, and they practice in English. There are different versions of the JSE. The versions are comparable in content. Slight changes are made in the words such that the text will be suitable for the planned health professionals. JSE HPS version17 has 20 items in a Likert-type format from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). It has 10 negatively worded items. The negatively worded items were items 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 18 and 19.17

The scoring of the questionnaire was according to the scoring algorithm of JSE. According to JSE, ‘a respondent must answer at least 16 (80%) of the 20 items; otherwise the form should be regarded as incomplete and excluded from the data analysis. If a respondent fails to answer 4 or fewer items, the missing values should be replaced with the mean score calculated from the items the respondent completed’.17 To score the questionnaire, the negatively worded items were reversed scored (from 1 [strongly agree] to 7 [strongly disagree]), while the other items are directly scored on their Likert weights from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total score was the sum of all item scores. The higher the total empathy scores, the higher the empathic behavioural orientation. The maximum total score for each participant is 140 and the minimum score is 20. Higher total scores indicate higher empathy, whereas lower total scores indicate lower empathy.17 According to the owners of JSE, it takes 5–10 min to complete, although they do not endorse a time limit for completing it.17

Psychometric properties

Construct validity and criterion-related validity of the JSE HPS version have been reported.18 Hojat et al17 have reported that internal consistency reliability of this version was 0.89 for medical students and 0.87 for house officers. Hojat et al4 has reported a test-retest reliability for the JSE HPS version as 0.65 (p<0.01). In their report, they said it was relatively low in magnitude, but acceptable for that kind of instrument considering the time interval between the test.4

Data analysis

Analysis of variance was used to test the hypothesis that there were statistically significant differences between the two groups at three time points. A Shapiro-Wilk’s test (p<0.05)19 20 and a visual inspection of their histograms showed variable scores were approximately normally distributed. I have included the results as supplementary file in the form of principal component analysis, χ2 test, independent t-test and Scree plot (see online supplementary tables 1–3 and figure 1).

A significance level of p<0.05 was planned. However, because several independent analyses (5) were performed on the data, the significance level of p<0.05 was adjusted to p<0.01 in interpreting the results using Bonferroni correction.21 ‘The Bonferroni correction is an adjustment made to p values when several dependent or independent statistical tests are being performed simultaneously on a single data set’.21 In this study, Bonferroni correction was computed by taking the critical p value (α) and divided it by the several dependent analyses (0.05/5) resulting in p<0.01. All data were analysed using SPSS.

Communication skills training

The author (MA), who was the main trainer, designed and developed the training guide using ‘Four Habits Model’22 and PCNF.13

Subsequently, the researcher trained a cotrainer (AAM) who assisted in the CST as well as in the data collection. The data was analysed by the author (MA) without blinding. The trainers used various methods to deliver the training. The methods were small group discussions, brainstorming, personal experience from participants, group reports, roleplaying, questions and answers, videos and summaries. Therefore, the training was on shared agenda. This approach made it possible for participants to share their previous training knowledge and ideas.

At the end of the training, participants were provided with photocopies of some relevant material as well as useful reference books and literature that will enable nurses and midwives to learn effective communication with patients.

Results

Demographic data

Participants (n=173) were made of intervention group (n=93) and control group (n=80). The demographic data are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Characteristics | Intervention group | Control group |

| (n=93) | (n=80) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age | ||

| >18 years | 5 (6) | 1 (1) |

| 19–21 years | 42 (45) | 32 (40) |

| 22–24 years | 41 (44) | 45 (57) |

| 25–27 years | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| 28–30 years | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| 31 years and above | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 68 (73) | 44 (55) |

| Male | 25 (27) | 36 (45) |

| Specialty | ||

| Nursing student | 62 (67) | 69 (86) |

| Midwifery students | 31 (33) | 11 (14) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 2 (2) | 9 (11) |

| Unmarried | 90 (97) | 70 (88) |

| Divorced | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 51 (55) | 30 (38) |

| Islam | 40 (43) | 48 (60) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Number of children | ||

| No child | 92 (99) | 72 (90) |

| One child | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Two children | 0 (0) | 4 (5) |

| Three children | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Four children and above | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Akan | 11 (12) | 5 (6) |

| Dagomba | 28 (30) | 34 (43) |

| Ewe | 2 (2) | 5 (6) |

| Fanti | 6 (6) | 3 (4) |

| Frafra (Grunsi) | 10 (12) | 2 (2) |

| Ga-Adangme | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Gonja | 8 (9) | 3 (4) |

| Kotokoli | 0 (0) | 3 (4 |

| Basare/Bisa | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Kasina/Bulsa | 0 (0) | 3 (4) |

| Dagati/Sisala | 5 (5) | 4 (5) |

| Other tribes | 20 (21) | 16 (20) |

| Academic writing and communication (AWC) | ||

| None | 10 (11) | 13 (16) |

| One week | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Two weeks | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Three weeks | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| One month | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Two months | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Three months | 3 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Four months (one semester) | 70 (75) | 57 (71) |

| Two semesters | 5 (6) | 6 (8) |

| Three semesters | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Four semesters | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Above four semesters | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

n=sample size in a particular group.

Descriptive statistics

The scores showed that there were slight increases in the intervention group from baseline T1 (M=109.8, SD=9.8, d=0.160) to post-test T2 (M=111.9, SD=9.0, d=0.201) as compared with the control group from baseline T1 (M=107.9, SD=11.5, d=0.160) to post-test T2 (M=110.0, SD=11.0, d=0.201) (table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of empathy

| Time | Group | N=173 | 95% CI for Cohen’s d | ||||

| n | M | SD | Cohen’s d | Lower | Upper | ||

| Baseline (T1) | Intervention | 93 | 109.8 | 9.8 | 0.160 | −0.139 | 0.458 |

| Control | 80 | 107.9 | 11.5 | ||||

| Post-test (T2) | Intervention | 93 | 111.9 | 9.0 | 0.201 | −0.098 | 0.499 |

| Control | 80 | 110.0 | 11.0 | ||||

| Follow-up (T3) | Intervention | 93 | 109.4 | 10.4 | −0.252 | −0.551 | 0.048 |

| Control | 80 | 111.9 | 8.3 | ||||

N, total sample size; n, group sample size; M, mean score.

Inferential statistics

This study showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the scores of empathy between the groups F(1, 171)=0.18, p=0.675 (table 3).

Table 3.

Inferential statistics empathy

| Source | Type III SS | df | MS | F | Sig. |

| Intercept | 6 259 179.09 | 1 | 6 259 179.09 | 55 379.73 | 0.000 |

| Group | 19.91 | 1 | 19.91 | .18 | 0.675 |

| Error | 19 326.92 | 171 | 113.02 |

Significance level p<0.01.

Measurement is by time point.

Transformed variable is by average.

Effect of the communication skills training, the empathy scores, and the demographic variables.

df, degrees of freedom; F, statistic; MS, mean square; Sig, significance level; SS, sum of squares.

In this study, there was no statistically significant effect between CST, the demographic variables of age, marital status, specialisation, ethnicity and religion as well as academic writing and communication (table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of the communication skills training, the empathy scores and the demographic variables

| Source | Type III SS | df | MS | F | Sig. |

| Intercept | 35 145.96 | 1 | 35 145.96 | 321.61 | 0.000 |

| Group*gender | 738.51 | 2 | 369.25 | 3.38 | 0.037 |

| Group*age | 431.25 | 2 | 215.63 | 1.97 | 0.142 |

| Group*marital status | 72.00 | 2 | 36.00 | 0.33 | 0.720 |

| Group*specialisation | 241.87 | 2 | 120.94 | 1.11 | 0.333 |

| Group*religion | 219.32 | 2 | 109.66 | 1.00 | 0.369 |

| Group*ethnicity | 440.74 | 2 | 220.37 | 2.02 | 0.137 |

| Group*AWC | 69.25 | 2 | 34.63 | 0.32 | 0.729 |

| Error | 17 266.55 | 158 | 109.28 |

Significance level p<0.01.

Measurement is by time point.

Transformed variable is by average.

AWC, academic writing and communication; df, degrees of freedom; F, statistic; MS, mean square; Sig., significance level; SS, sum of squares.

Discussions

In this study, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups F(1, 171)=0.18, p=0.675 (table 3). The findings from this study are in contrast to the findings from a similar study that showed enhancement of empathy in nurses.23–26 For example, a study reported that nursing students empathy moderately increased in scores (M=88.63; SD=8.93).23 24 Further in contrast, another study found statistically significant effect in empathy scores following a training.25

Research has shown that there are a number of studies that doubt the effectiveness of empathy training programmes in nursing education and rather reported stability in empathy.27–35 A study by La Monica et al30 did not find improvement in empathy outcomes. In a related study, they found stability in empathy after a short-term education (M=20.7–22.6; SD=3.0–5.0).31 In another research, it was reported that empathy was stable.32

Research has demonstrated that there is a relationship between empathy and demographic variables of gender, education and experience. In this study, there were no statistically significant differences in empathy and the demographic variables of gender, age, marital status, specialisation, religion, number of children and ethnicity between the both groups. The findings from this study are inconsistent with other studies where females empathy scores are reported to be higher than male empathy scores.23–25 36–42 For example, a study has demonstrated statistical significance in female empathy than male empathy (p<0.001).24 In addition, women were reported to show increase in mean empathy score than male colleagues (M=5.55, SD=0.46 and M=5.35, SD=0.55,39 respectively).

This has further been buttressed in another study where the mean female empathy score (M=110.8; SD=11.7) was reportedly higher than that of male empathy score (M=105.3; SD=13.5; p=0.0001; d=0.44).25 In contrast, there have been reports of stability in empathy between women and men.42

Despite the above evidence of empathy in some nursing research in the short term following empathy training, there have been some doubts on empathy follow-up research.37 43 44 In this study, empathy did not show any statistically significant difference between the groups in a follow-up after 6 months. This study is consistent with another study that found nursing empathy after training did not improve after five times measurement (F(1, 29)=3.91, p<0.06).43 This doubt in follow-up has also been reported in an earlier study by Daniels et al.45

In contrast, another study found empathy increased 3 months after CST.44 However, another study reported decreases in empathy as students advance through their nursing programme.46

It has also been found by some researchers that there is a positive correlation between nursing students empathy and patient outcomes.47–50 Yu and Kirk,51 in a systematic review of measurement of empathy in nursing research, indicated that in eight appraisal researches, there was enhancement of empathy levels of students but that it was unclear if such enhancement was sustainable.

The results from this study confirm previous studies findings on nursing and midwifery training that empathy cannot be enhanced in a short period following CST.31–35 42 43 With this similar finding, there is a need for further studies to determine the effectiveness of CST in enhancing NMS empathy.

Most of the studies have focused on empathy levels of nurses, differences in empathy, relationship between empathy and demographics variables.51 However, there are limited studies in the area of empathy in NMS. There are varied studies and the results from the previous studies show low,45 47 moderately enhanced23 52 and high levels23 34 52–56 of self-reported nurses’ empathy. Other findings on nursing and midwifery training have contradicted this current study by indicating that empathy can be enhanced with training.24 25 41 However, some studies have found that NMS empathy actually decreases after training.46 57 Other variables like age, gender, education and religion have been considered in research.23

Despite the fact that some studies have focused on empathy training among healthcare professionals including NMS in other countries, there are no known studies in Ghana. This study will therefore add to the literature on how best to enhance CST.

Conclusions

This study has shown that empathy may not be enhanced within a short period after CST. The participants were made aware of empathy being an outcome of this study and since JES is self-reported, it may have impacted their self-report. Selection bias may have impacted the lack of significance. It is possible that participants that volunteered were more empathetic compared with baseline and JES is self-reported. More so, the 2-day training time was not enough and that could have accounted for no enhancement of empathy.

This is the first RCT using CST in a nursing and midwifery school in Ghana. A study of this nature may better be evaluated by multicentre location in RCT across several regions. This may offer a much better comparison.

In this study, the women outnumbered the men both in the intervention and control. This is a limitation in the sense that women turn to be empathetic than men. Also, 99% of participants were either Christians or Muslims, as one is aware that religion teaches its members to be empathetic towards one another and this could have an effect on the outcome of this study.

Despite the limitations and strengths of this current study, the following recommendations are made for future studies. This CST had used a 2-day training period. A longer training period could have offered a better comparison. It does look like participants did not have the opportunity to read and reflect on the 2-day training before the post-test. This study used one location and a multicentre location in RCT across several nursing and midwifery schools probably could provide better outcomes.

This study explored the effect of CST post-test and 6 months post-training; however, a long-term examination could have been very useful. Further studies exploring the longer-term impact of the CST in other healthcare professionals and multi-location using cluster sampling may be beneficial. There is a need for additional studies to find out which aspects of CST for NMS will enhance empathy.

bmjopen-2018-023666supp001.pdf (52.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023666supp002.pdf (32.4KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author (MA) wishes to thank the research assistant (AAM), management of Tamale Nursing and Midwifery college and the nursing and midwifery students for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA designed, undertook data collection, data integrity, accuracy of the analyses and writing of this article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Research and Monitoring Department of Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale – Ghana, gave Ethical approval for this study on 5th May 2013. The approval number is TTH/R6M/SR/13/12.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (extra data are available by emailing mustaph@uds.edu.gh).

Author note: MA is a lecturer at the University for Development Studies, School of Allied Health Sciences, Tamale - Ghana.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Reynolds WJ, Scott B. Do nurses and other professional helpers normally display much empathy? J Adv Nurs 2000;31:226–34. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCabe C, Timmins F. Communication skills for nursing practice. Palgrave Macmillan 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reynolds WJ, Scott B, Jessiman WC. Empathy has not been measured in clients’ terms or effectively taught: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 1999;30:1177–85. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, et al. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1563–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alligood MR. Chapter 17: Rethinking Empathy in Nursing Education: Shifting to a Developmental View. Annu Rev Nurs Educ 2015. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P3-842569171.html (accessed 2 Feb 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frankel RM, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. J Med Pract Manage 2001;16:184–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns 2005;58:4–12. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roter DL. Physician/patient communication: transmission of information and patient effects. Md State Med J 1983;32:260–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roter DL. Patient question asking in physician-patient interaction. Health Psychol 1984;3:395–409. 10.1037/0278-6133.3.5.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 587: Effective patient-physician communication. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:389–93. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000443279.14017.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rogers CR. Client-centred therapy: its current practice, implications and theory. Houghton Mifflin 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Egan G. The skilled helper: a problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping. Cengage Learning 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred Nursing: Theory and Practice: Wiley, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roter D, Hall J, Kern D, et al. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ em. 1975. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7677554 (accessed 1 Jan 2015). [PubMed]

- 15. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149–60. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Universität Düsseldorf: G*Power. http://www.gpower.hhu.de/ (accessed 3 Sep 2018).

- 17. Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas 2001;61:349–65. 10.1177/00131640121971158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krupat E, Frankel R, Stein T, et al. The Four Habits Coding Scheme: validation of an instrument to assess clinicians’ communication behavior. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:38–45. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965;52:591–611. 10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Razali NM, Wah YB. Power comparisons of shapiro-wilk, kolmogorov-smirnov, lilliefors and anderson-darling tests. J Stat Model Anal 2011;2:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995;310:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gulbrandsen P, Krupat E, Benth JS, et al. ‘Four Habits’ goes abroad: report from a pilot study in Norway. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:388–93. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bailey S. Levels of empathy of critical care nurses. Aust Crit Care 1996;9:121–7. 10.1016/S1036-7314(96)70369-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ouzouni C, Nakakis K. An exploratory study of student nurses’ empathy. Health Sci J 2012;6:534. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cutcliffe JR, Cassedy P. The development of empathy in students on a short, skills based counselling course: a pilot study. Nurse Educ Today 1999;19:250–7. 10.1016/S0260-6917(99)80011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bas-Sarmiento P, Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Baena-Baños M, et al. Efficacy of empathy training in nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today 2017;59:59–65. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moore PM, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M, et al. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:CD003751 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okaya K. Reliance between a patient and a nurse. Nurs Today 1995;10:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alligood MR. Empathy: the importance of recognizing two types. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1992;30:14–17. 10.3928/0279-3695-19920301-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. La Monica EL, Wolf RM, Madea AR, et al. Empathy and nursing care outcomes. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 1987;1:197–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reynolds WJ, Presly AS. A study of empathy in student nurses. Nurse Educ Today 1988;8:123–30. 10.1016/0260-6917(88)90029-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hodges SA. An experiment in the development of empathy in student nurses. J Adv Nurs 1991;16:1296–300. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams B, Brown T, Boyle M, et al. Levels of empathy in undergraduate emergency health, nursing, and midwifery students: a longitudinal study. Adv Med Educ Pract 2014;5:299–306. 10.2147/AMEP.S66681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pålsson MB, Hallberg IR, Norberg A, et al. Burnout, empathy and sense of coherence among Swedish district nurses before and after systematic clinical supervision. Scand J Caring Sci 1996;10:19–26. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1996.tb00305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lauder W, Reynolds W, Smith A, et al. A comparison of therapeutic commitment, role support, role competency and empathy in three cohorts of nursing students. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2002;9:483–91. 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, et al. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1434–8. 10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, et al. Empathy in medical students as related to academic performance, clinical competence and gender. Med Educ 2002;36:522–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kataoka HU, Koide N, Hojat M, et al. Measurement and correlates of empathy among female Japanese physicians. BMC Med Educ 2012;12:48 10.1186/1472-6920-12-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Empathy in UK medical students: differences by gender, medical year and specialty interest. Educ Prim Care 2011;22:297–303. 10.1080/14739879.2011.11494022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. SAGE 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Williams B, Brown T, McKenna L, et al. Empathy levels among health professional students: a cross-sectional study at two universities in Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract 2014;5:107–13. 10.2147/AMEP.S57569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kliszcz J, Nowicka-Sauer K, Trzeciak B, et al. Empathy in health care providers–validation study of the Polish version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. Adv Med Sci 2006;51:219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Evans GW, Wilt DL, Alligood MR, et al. Empathy: a study of two types. Issues Ment Health Nurs 1998;19:453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yates P, Hart G, Clinton M, et al. Exploring empathy as a variable in the evaluation of professional development programs for palliative care nurses. Cancer Nurs 1998;21:402–10. 10.1097/00002820-199812000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Daniels TG, Denny A, Andrews D. Using microcounseling to teach RN nursing students skills of therapeutic communication. J Nurs Educ 1988;27:246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Enduring impact of communication skills training: results of a 12-month follow-up. Br J Cancer 2003;89:1445–9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reid-Ponte P. Distress in cancer patients and primary nurses’ empathy skills. Cancer Nurs 1992;15:283–92. 10.1097/00002820-199208000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Murphy PA, Forrester DA, Price DM, et al. Empathy of intensive care nurses and critical care family needs assessment. Heart Lung 1992;21:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Olson JK. Relationships between nurse-expressed empathy, patient-perceived empathy and patient distress. Image J Nurs Sch 1995;27:317–22. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1995.tb00895.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Olson J, Hanchett E. Nurse-expressed empathy, patient outcomes, and development of a middle-range theory. Image J Nurs Sch 1997;29:71–6. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu J, Kirk M. Measurement of empathy in nursing research: systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2008;64:440–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04831.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Watt-Watson J, Garfinkel P, Gallop R, et al. The impact of nurses’ empathic responses on patients’ pain management in acute care. Nurs Res 2000;49:191–200. 10.1097/00006199-200007000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aström S, Nilsson M, Norberg A, et al. Empathy, experience of burnout and attitudes towards demented patients among nursing staff in geriatric care. J Adv Nurs 1990;15:1236–44. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01738.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aström S, Nilsson M, Norberg A, et al. Staff burnout in dementia care–relations to empathy and attitudes. Int J Nurs Stud 1991;28:65–75. 10.1016/0020-7489(91)90051-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Warner RS. Nurses’ empathy and patients’ satisfaction with nursing care. J N Y State Nurses Assoc 1992;23:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kuremyr D, Kihlgren M, Norberg A, et al. Emotional experiences, empathy and burnout among staff caring for demented patients at a collective living unit and a nursing home. J Adv Nurs 1994;19:670–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kazanowski MK, Bennett LA. Engendering Empathy in Baccalaureate Nursing Students.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023666supp001.pdf (52.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023666supp002.pdf (32.4KB, pdf)