Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services across 31 Sub-Saharan African countries.

Design, setting and participants

We analysed the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (2010–2016) data collected from married women aged 15–49 years. We used four DHS measures related to women’s autonomy: attitude towards domestic violence, attitude towards sexual violence, decision making on spending of household income made by the women solely or jointly with husbands and decision making on major household purchases made by the women solely or jointly with husbands. We used multiple logistic regression analyses to examine the association between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services adjusted for five potential confounders: place of residence, age at birth of the last child, household wealth, educational attainment and working status. Adjusted ORs (aORs) and 95% CI were used to produce the forest plots.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the utilisation of ≥4 antenatal care visits and delivery by skilled birth attendants (SBA).

Results

Pooled results for all 31 countries (194 883 women) combined showed weak statistically significant associations between all four measures of women’s autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services (aORs ranged from 1.07 to 1.15). The strongest associations were in the Southern African region. For example, the aOR for women who made decisions on household income solely or jointly with husbands in relation to the use of SBAs in the Southern African region was 1.44 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.70). Paradoxically, there were three countries where women with higher autonomy on some measures were less likely to use maternal healthcare services. For example, the aOR in Senegal for women who made decisions on major household purchases solely or jointly with husbands in relation to the use of SBAs (aOR=0.74 95% CI 0.59 to 0.94).

Conclusion

Our results revealed a weak relationship between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services. More research is needed to understand why these associations are not stronger.

Keywords: antenatal care, autonomy, sub-Saharan Africa, empowerment, skilled birth attendants, maternal health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used nationally representative Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) datasets from 31 Sub- Saharan African countries.

We used four separate measures of women’s autonomy.

DHS data are cross-sectional, and so the direct relationship between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services cannot be determined with certainty.

Introduction

Maternal mortality, measured as maternal mortality ratio (MMR), remains a major concern despite the decline globally from 385 to 216 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births between 1990 and 2015.1 Sixty-six per cent of all maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).1 This is of concern if SSA is to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 3 target of fewer than 70 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births by 2030.1 The leading causes of maternal deaths in SSA are abortion, haemorrhage, hypertension, obstructed labour and sepsis.2 Increasing the utilisation of antenatal care (ANC) and skilled birth attendants (SBA) could help reduce the high number of maternal deaths in SSA.3–7

A better understanding of the relationship between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services may contribute to reducing maternal deaths in SSA. However, examining women’s autonomy is not without challenges, especially disagreements related to its measurement and definition.8–11 Similar to several other studies conducted in developing countries, in this study, we assessed women’s autonomy using four measures included in Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) questionnaires.8–11 Some scholars have used the terms ‘autonomy’ and ‘empowerment’ interchangeably while others have argued that the two words differ.12–16 In this study, we use the term ’autonomy' to indicate women’s ability to make an independent decision, to manipulate the environment and control resources, as well as to engage and hold accountable institutions.17–20

Most of the studies that have examined the relationship between women’s autonomy and women’s health were conducted in South and South-East Asia.14 15 18 21–23 These studies have found that women’s autonomy is essential for the utilisation of maternal healthcare services and women’s well-being. However, a recent review by Osamor and Grady found few relevant studies from SSA, making it difficult to know if these results apply there.10 24–28 The aim of our study was to examine the association between four measures of women’s autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services across 31 SSA countries using DHS data collected during 2010–2016.

Methods

Data source

Data from DHS surveys were used. This study is restricted to married women aged 15–49 years at the time the DHS surveys were conducted. DHS surveys are standardised cross-sectional data sets that are publicly available. Data are collected by the National Statistics Agencies in collaboration with the United States Agency for International Development.29

Sampling methods

DHS surveys use probability sampling methods to produce representative national samples of women aged 15–49 years. The sample results are weighted to ensure the results are relevant to each country.30 DHS surveys collect information on a wide range of topics using mainly identical questionnaires in all countries.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

From the 49 SSA countries, we selected the 31 countries that had had DHS data collected during 2010–2016. We divided the 31 countries into four regions, as used by the Global Burden of Disease Study2: Central Africa (Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo and Gabon); Eastern Africa (Burundi, Comoros, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia); Southern Africa (Lesotho, Namibia, and Zimbabwe); and Western Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo). Note that South Africa was excluded as its latest DHS was conducted in 1992. We restricted our analysis to the most recent child born in the 5 years preceding each survey to improve the accuracy of recall of use of maternal healthcare services.

Study variables

Outcome variables

We examined two outcome measures: utilisation of at least four ANC visits (≥4 ANC) and delivery of the last child by SBA. The utilisation of SBA included births attended by doctors, midwives and village midwives; non-utilisation included births attended by traditional birth attendants, family members and other relatives.31 The utilisation of ANC services was based on mothers who had at least four ANC visits as recommended by the WHO.5 There was no data on the time of each ANC visit. Primary outcome measures took a binary form: women with the recommended four or more ANC services were assigned ‘1’, and women who reported less than the four recommended ANC services were assigned ‘0’. Delivery with any SBA was categorised as‘1’, and delivery without SBA was categorised as ‘0’.

Explanatory variables

We used four DHS indicators related to women’s autonomy in two areas: women’s attitudes to sexual and domestic violence32–38 and participation in decision-making (solely or jointly with the husband) on spending of household income and major household purchases.9 10 39–41

Attitude to sexual violence was measured based on responses to a question that asked if beating a wife by a husband for refusing sexual intercourse with him is acceptable. We coded a woman with a score of 1 if she responded ‘no’ (positive association with autonomy) and 0 if she responded ‘yes’ (agreement). Attitude to domestic violence was based on responses of women to four DHS questions asking whether a husband was justified in beating his wife if she goes out without telling him; neglects the children; argues with him; or burns the food. We coded a woman with a score of 1 if she responded with ’no' to all four DHS questions (positive association with empowered) and 0 if she responded ‘yes’ (agreement) to any question.

Autonomy about household income was based on a question on spending of household income. Autonomy concerning decision-making on major household purchases was based on a question regarding who decides on major household purchases. We coded the answers to these two questions as 1 (positive association with autonomy) if a woman chooses solely or jointly with the husband and 0 if the husband alone or someone else makes the decision.

Potential confounding factors

We adjusted for five potential confounding factors based on previous literature in low-income and middle-income countries: place of residence (urban/rural),42–45 mother’s age at birth,46 mother’s educational attainment,26 46 47 household wealth index26 46–48 and mother’s working status.46 47

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses involved frequency tabulations of all selected socio-economic and demographic characteristics of women in each country (descriptive analysis). Then, logistic regression modelling was done to assess the associations between autonomy measures and outcome measures (≥4 ANC and SBA) using generalised linear latent and mixed models with the logit link and binomial family that adjusts for DHS clustering and sampling weights.49

Our analysis was conducted in four stages where data were entered progressively into the model to assess associations with the study outcomes. In model 1, we conducted logistic regression models with each measure of autonomy and each outcome variable (≥4 ANC and SBA). In the second stage, to avoid collinearity, the socio-economic factors (mother’s education, household wealth index and mother’s working status) were entered into model 1 to examine their association with the study outcomes (model 2). In the third stage, individual-level factors (place of residence, mother’s age at birth) were added to model 2 to form model 3. Last, the primary explanatory variables (autonomy) were added to model 3 to form the final model 4. As all five potential confounders were significant at p values <0·05, they were retained in the final model.

Adjusted ORs and 95% CI were used to measure the level of association between the four explanatory autonomy variables and the two outcome variables in each of the 31 studied countries. The ‘metan’ function in STATA was used to produce the forest plots of aORs and 95% CIs in individual countries for all 31 countries combined, and for countries in each of the four SSA regions. All analyses and plots were performed using STATA V.14.2.50

Patient and public involvement

We had no contact with any patients or the public for this study as we used publicly accessible data previously collected for National Demographic and Health Surveys.

Results

Table 1 shows socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the women in our sample (n=194 883). There was considerable variation among the 31 countries. Ninety-two per cent of women surveyed in Burundi lived in rural areas compared with just 14% surveyed in Gabon. The percentage of women who gave birth to their first child at age 12–17 years was highest in Ethiopia (62%) and lowest in Rwanda (6%). The percentage of surveyed women with no education was highest in Burkina Faso (83%) and lowest in Lesotho and Zimbabwe (1%). The percentage of surveyed women who were unemployed was highest in Niger (77%) and lowest in Rwanda (14%). The three countries with the highest percentage of surveyed women having at least primary education were all in the Southern African region: Lesotho (99%), Namibia (92%) and Zimbabwe (99%).

Table 1.

Socio-economic and demographic characteristics of surveyed married women aged 15–49 years living with their male partners

| Sub-Saharan African regions (n=31) | Country (year of DHS) | Residency | Age at first childbirth | Educational attainment | Work status | |||||||

| Urban | Rural | 30+ | 24–29 | 18–23 | 12–17 | No education | Primary | Secondary or higher | Not working | Working | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| West (15) | Benin (2011–2012) | 3350 (40.1) | 5021 (59.9) | 238 (2.8) | 13 960 (16.7) | 4299 (51.4) | 2439 (29.14) | 6032 (72.1) | 1372 (16.4) | 966 (11.5) | 2577 (30.8) | 5794 (69.2) |

| Burkina Faso (2010) | 1826 (18.1) | 8307 (81.9) | 80 (0.8) | 675 (6.7) | 6031 (59.5) | 3347 (33.03) | 8454 (83.5) | 1113 (11.0) | 561 (5.5) | 2246 (22.2) | 7886 (77.8) | |

| Cameroon (2011) | 2824 (43.2) | 3709 (56.8) | 71 (1.1) | 584 (8.9) | 3227 (49.4) | 2651 (40.57) | 1922 (29.4) | 2488 (38.1) | 2123 (32.5) | 2023 (31.0) | 4510 (69.0) | |

| Chad (2014–2015) | 1910 (18.7) | 8319 (81.3) | 68 (0.7) | 545 (5.3) | 3987 (38.9) | 5629 (55.03) | 6807 (66.5) | 2383 (23.3) | 1040 (10.2) | 5766 (56.4) | 4453 (43.6) | |

| Cote d’Ivoire (2011–2012) | 1640 (37.9) | 2677 (62.0) | 48 (1.1) | 396 (9.2) | 2134 (49.4) | 1739 (40.3) | 2858 (66.2) | 1052 (24.4) | 407 (9.4) | 1210 (28.0) | 3107 (72.0) | |

| Gambia 2013) | 2355 (48.2) | 2536 (51.9) | 79 (1.6) | 619 (12.7) | 2574 (52.6) | 1618 (33.1) | 2960 (60.5) | 678 (13.9) | 1252 (25.6) | 2555 (52.3) | 2335 (47.8) | |

| Ghana (2014) | 1576 (45.8) | 1870 (54.3) | 168 (4.9) | 716 (20.8) | 1789 (51.9) | 772 (22.4) | 985 (28.6) | 642 (18.6) | 1819 (52.8) | 649 (18.8) | 2797 (81.2) | |

| Guinea (2012) | 1175 (25.8) | 3377 (74.2) | 59 (1.3) | 359 (7.9) | 1849 (40.6) | 2286 (50.2) | 3605 (79.2) | 536 (11.8) | 411 (9.0) | 902 (19.8) | 3650 (80.2) | |

| Liberia (2013) | 1763 (50.6) | 1721 (49.4) | 30.70 (0.9) | 271 (7.8) | 1722 (49.5) | 1459 (41.9) | 1575 (45.2) | 999.90 (28.7) | 908 (26.1) | 1377 (39.5) | 2106 (60.5) | |

| Mali (2012–2013) | 1284 (19.6) | 5269 (80.4) | 109 (1.7) | 594 (9.1) | 2998 (45.7) | 2852 (43.5) | 5460 (83.3) | 579 (8.8) | 515 (7.9) | 3691 (56.3) | 2863 (43.7) | |

| Niger (2012) | 1089 (13.9) | 6718 (86.1) | 57 (0.7) | 508 (6.5) | 3348 (43.0) | 3872 (49.7) | 6634 (85.1) | 785 (10.1) | 380 (4.9) | 6002 (76.9) | 1804 (23.1) | |

| Nigeria (2013) | 6830 (35.2) | 12 567 (64.8) | 543 (2.8) | 2646 (13.6) | 8525 (44.0) | 7683 (39.6) | 9575 (49.4) | 3679 (19.0) | 6143 (31.7) | 6067 (31.3) | 13 311 (68.7) | |

| Senegal (2010–2011) | 1468 (36.5) | 2555 (63.5) | 96 (2.4) | 558 (13.9) | 2241 (55.7) | 1128 (28.0) | 2719 (67.6) | 838 (20.8) | 467 (11.6) | 2225 (55.3) | 1799 (44.7) | |

| Sierra Leone (2013) | 1704 (23.4) | 5571 (76.6) | 110 (1.5) | 777 (10.7) | 3435 (47.2) | 2950 (40.6) | 5287 (72.7) | 1017 (14.0) | 970 (13.3) | 1641 (22.6) | 5626 (77.4) | |

| Togo (2013–2014) | 1602 (36.2) | 2824 (63.8) | 132 (3.0) | 720 (16.3) | 2523 (57.0) | 1050 (23.7) | 1789 (40.4) | 1608 (36.3) | 1030 (23.3) | 849 (19.2) | 3577 (80.8) | |

| East (10) | Burundi (2010) | 359 (8.0) | 4146 (92.0) | 77 (1.7) | 716 (15.9) | 3071 (68.2) | 640 (14.2) | 2361 (52.4) | 1863 (41.4) | 282 (6.3) | 818 (18.2) | 3687 (81.8) |

| Comoros (2012) | 555 (28.6) | 1385 (71.4) | 139 (7.1) | 405 (20.9) | 830 (42.8) | 567 (29.2) | 841 (43.5) | 482 (24.9) | 611 (31.6) | 1171 (60.5) | 764 (39.5) | |

| Ethiopia (2016) | 882 (12.4) | 6227 (87.6) | 52 (0.7) | 363 (5.2) | 2223 (31.7) | 4379 (62.4) | 4508 (63.4) | 1995 (28.1) | 605 (8.5) | 5138 (72.3) | 1971 (27.7) | |

| Kenya (2014) | 4481 (38.1) | 7284 (61.9) | 154 (1.3) | 1429 (12.2) | 6822 (58.0) | 3359 (28.6) | 1251 (10.6) | 64 160 (54.5) | 4099 (34.8) | 1972 (35.3) | 3611 (64.7) | |

| Malawi (2015–2016) | 1608 (14.4) | 9572 (85.6) | 72 (0.6) | 569 (5.1) | 6549 (58.6) | 3990 (35.7) | 1404 (12.6) | 7389 (66.1) | 2387 (21.4) | 3814 (34.1) | 7366 (65.9) | |

| Mozambique (2015) | 800 (26.0) | 2282 (74.0) | 46 (1.5) | 170 (5.6) | 995 (32.6) | 1837 (60.3) | 884 (28.7) | 1710 (55.5) | 480 (15.9) | 1877 (60.9) | 1206 (39.1) | |

| Rwanda (2014–2015) | 794 (16.4) | 4050 (83.6) | 161 (3.3) | 1262 (26.1) | 3107 (64.1) | 313 (6.5) | 717 (14.8) | 3513 (72.5) | 614 (12.7) | 672 (13.9) | 4172 (86.1) | |

| Tanzania (2015–2016) | 1571 (27.6) | 4115 (72.4) | 79 (1.4) | 528 (9.3) | 3401 (59.9) | 1675 (29.5) | 1168 (20.5) | 3695 (65.0) | 824 (14.5) | 1283 (22.6) | 4403 (77.4) | |

| Uganda (2016) | 1834 (22.2) | 6422 (77.8) | 136 (1.7) | 592 (7.2) | 3709 (45.2) | 3773 (46.0) | 890 (10.8) | 4975 (60.3) | 2392 (29.0) | 1746 (21.1) | 6510 (78.9) | |

| Zambia (2013–2014) | 2694 (36.3) | 4730 (63.7) | 60 (0.8) | 420 (5.7) | 4070 (54.8) | 2875 (38.7) | 813 (11.0) | 4170 (56.2) | 2435 (32.8) | 3397 (45.8) | 4026 (54.2) | |

| Central (3) | Congo, Rep. (2011–2012) | 2764 (62.1) | 1690 (38.0) | 83 (1.9) | 469 (10.5) | 2317 (52.0) | 1586 (35.6) | 319 (7.2) | 1307 (29.3) | 2829 (63.5) | 1288 (28.9) | 3166 (71.1) |

| DRC (2013–2014) | 2867 (30.7) | 6469 (69.3) | 126 (1.3) | 925 (9.9) | 5179 (55.5) | 3104 (33.3) | 1762 (18.9) | 4035 (43.2) | 3539 (37.9) | 2277 (24.4) | 7058 (75.6) | |

| Gabon (2012) | 2199 (85.6) | 371 (14.4) | 74 (2.9) | 294 (11.4) | 1261 (49.1) | 941 (36.6) | 230 (9.0) | 639 (24.9) | 1700 (66.2) | 1338 (52.1) | 1228 (47.9) | |

| Southern (3) | Lesotho (2014) | 574 (28.6) | 1434 (71.4) | 58 (2.9) | 243 (12.1) | 1364 (67.9) | 343 (17.1) | 20 (1.0) | 902 (44.9) | 1086 (54.1) | 1318 (65.6) | 690 (34.4) |

| Namibia (2013) | 944 (53.4) | 826 (46.7) | 81 (4.6) | 324 (18.3) | 934 (52.8) | 431 (24.4) | 136 (7.7) | 442 (25.0) | 1192 (67.4) | 967 (54.7) | 801 (45.3) | |

| Zimbabwe (2015) | 1355 (32.1) | 2864 (67.9) | 42.60 (1.0) | 393 (9.3) | 2688 (63.7) | 1095 (26.0) | 51 (1.22) | 1304 (30.9) | 2864 (67.9) | 2478 (58.8) | 1740 (41.3) | |

Data from Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in 31 sub-Saharan Africa countries, (2010–2016).

DHS, Demographic and Health Surveys.

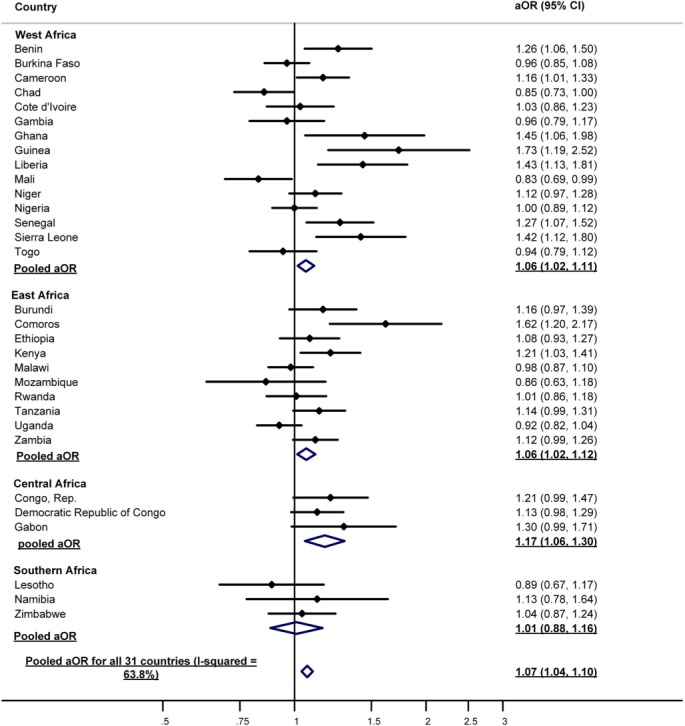

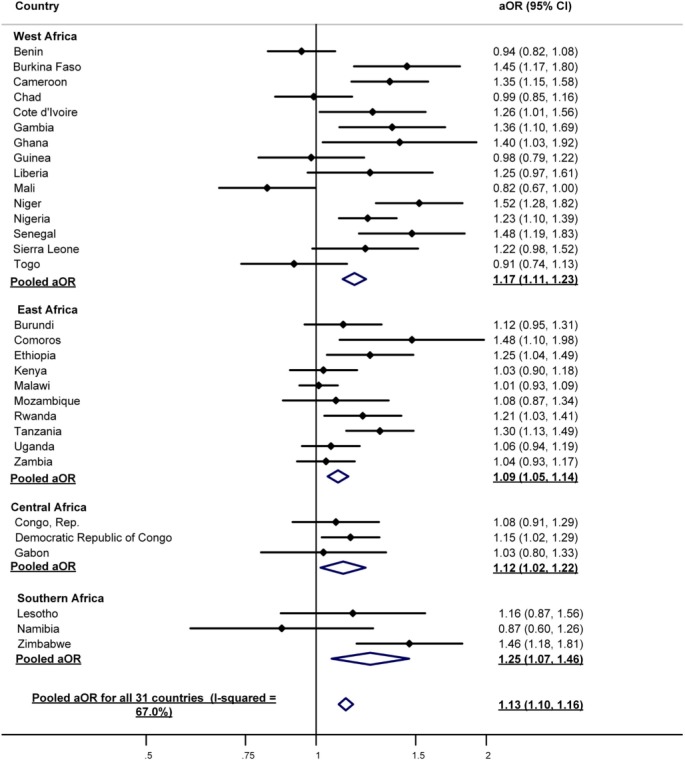

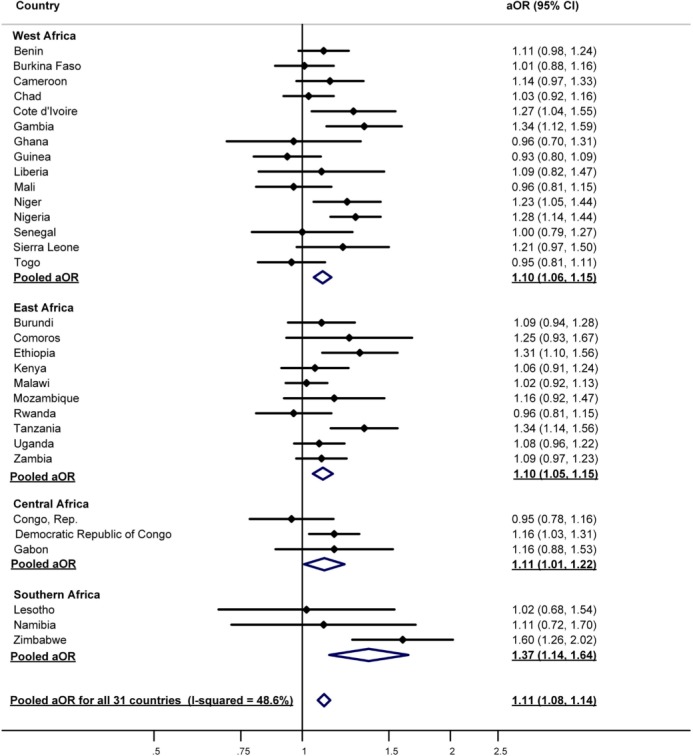

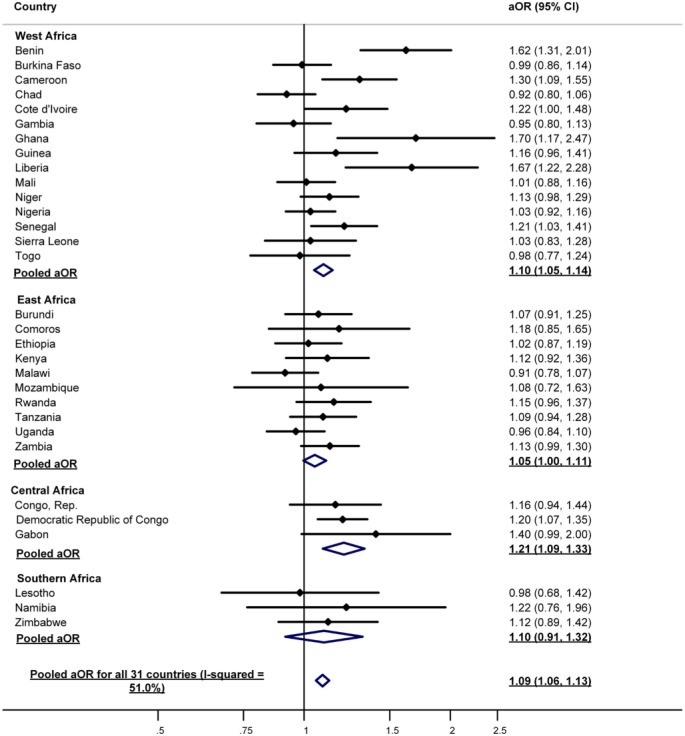

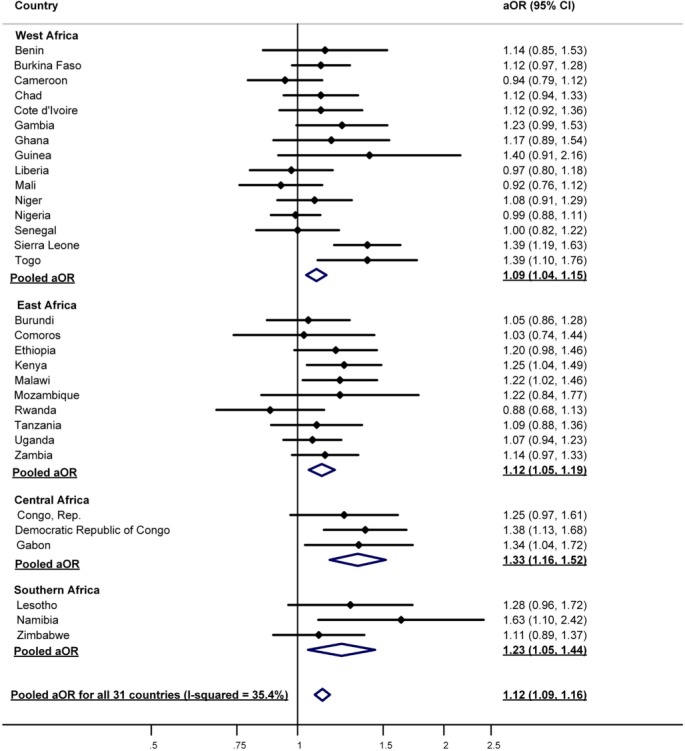

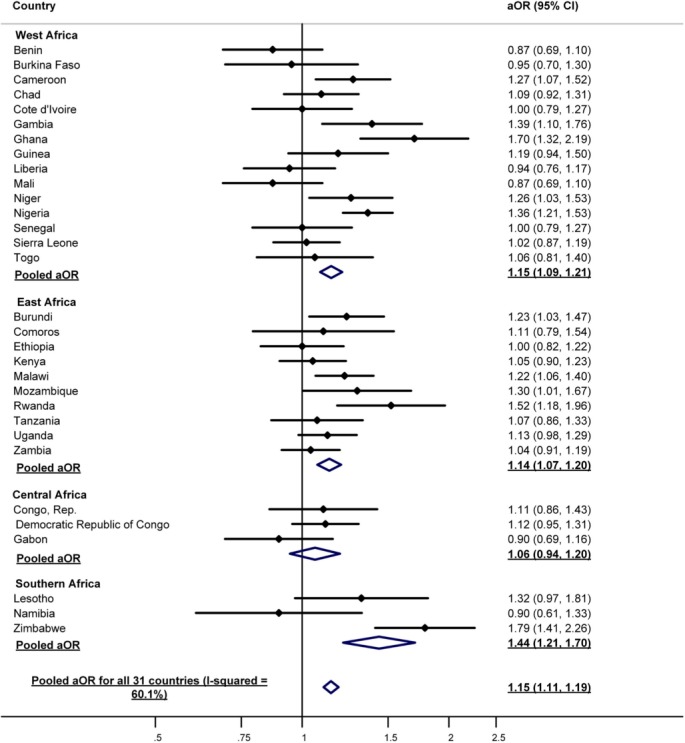

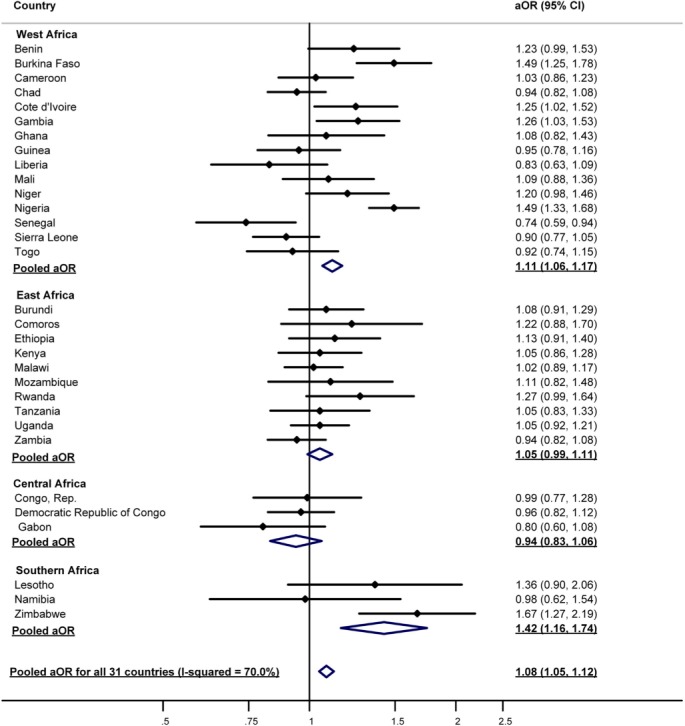

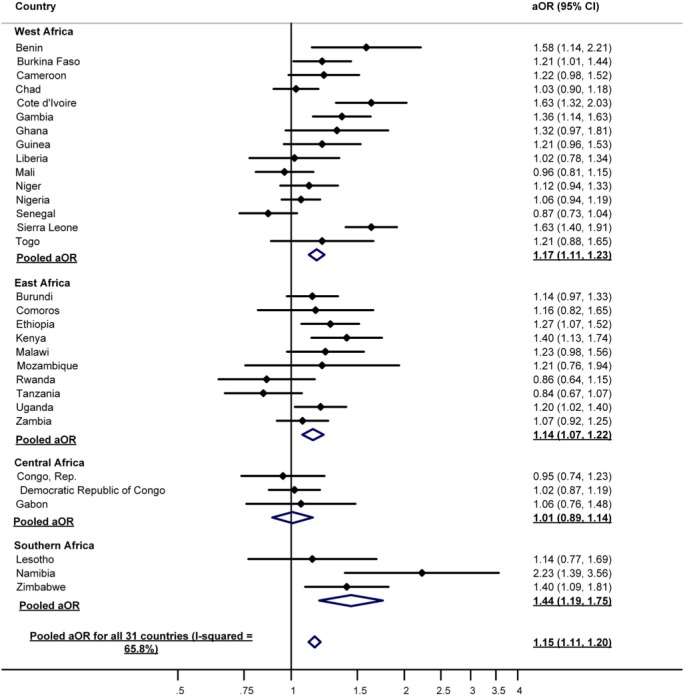

Figures 1–4 (≥4 ANC) and figures 5–8 (SBA) summarise the meta-analysis results (aORs and 95% CI) for all 31 countries combined, as well as for regions and individual countries (after adjusting for the five potential confounders). Pooled results for all 31 countries (194 883 women) combined showed weak statistically significant associations between all four measures of women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal services. Associations were strongest in the Southern African region (figures 1–8).

Figure 1.

The association between women’s autonomy (opposing domestic violence) and utilisation of ≥4 antenatal care visits in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

Figure 2.

The association between women’s autonomy (decisions making on spending of household income) and utilisation of ≥4 antenatal care visits in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

Figure 3.

The association between women’s autonomy (decision making on major household purchases) and utilisation of ≥4 antenatal care visits in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

Figure 4.

The association between women’s autonomy (opposing sexual violence) and utilisation of ≥4 antenatal care (ANC) visits in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016

Figure 5.

The association between women’s autonomy (opposing domestic violence) and utilisation of skilled birth attendants in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

Figure 6.

The association between women’s autonomy (decisions making on spending of household income) and utilisation of skilled birth attendants in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

Figure 7.

The association between women’s autonomy (decision-making on major household purchases) and utilisation of skilled birth attendant in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

Figure 8.

The association between women’s autonomy (opposing sexual violence) and utilisation of the skilled birth attendant in 31 Sub-Saharan African countries, 2010–2016.

The pooled aORs and 95% CIs for all 31 SSA countries and utilisation of ≥4 ANC visits were: (1) for opposing domestic violence (aOR=1.07 95% CI 1.04 to 1.10); (2) for decision-making on major household income (aOR=1.13 95% CI 1.10 to 1.16); (3) for decision-making on major household purchases (aOR=1.11 95% CI 1.08 to 1.14); and (4) for opposing sexual violence (aOR=1.09 95% CI 1.06 to 1.13).

The pooled aORs and 95% CI for all 31 SSA countries and utilisation of SBA visits were: (1) for opposing domestic violence (aOR=1.12 95% CI 1.09 to 1.16); (2) for decision-making on major household income (aOR=1.15 95% CI 1.11 to 1.19); (3) for decision-making on major household purchases (aOR=1.08 95% CI 1.05 to 1.12); and (4) for opposing sexual violence (aOR=1.15 95% CI 1.1 to 1.20).

Interestingly, our country-level analyses showed that in three countries (Chad, Mali and Senegal), women with higher autonomy were less likely to use maternal healthcare services. Women with higher autonomy about domestic violence were less likely to use ≥4 ANC in Chad (aOR=0.85, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.00) and Mali (aOR=0.83, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.99) (figure 1). Women who made decisions on household income were less likely to use ≥4 ANC in Mali (aOR=0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.00) (figure 2). Women who made decisions on major household purchases were less likely to use SBAs in Senegal (aOR=0.74, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.94) (figure 7).

Discussion

Our pooled results for all 31 countries showed weak, although statistically significant associations between women’s autonomy and use of both ≥4 ANC and SBAs. The exception was the Southern African region where three measures of women’s autonomy were relatively strongly associated with the use of maternal healthcare services. Surprisingly, the country-level analyses suggested that in Chad, Mali and Senegal, women with higher autonomy on some measures were less likely to use maternal healthcare services.

Although our combined pooled results for all 31 countries show that women’s autonomy is associated with the use of maternal healthcare services in SSA, this association was weak, suggesting that many factors other than women’s autonomy affect the use of maternal healthcare services. In a study similar to ours, Ahmed et al51 used DHS data to investigate the autonomy and utilisation of ≥4 ANC and SBA in 31 developing countries, including 21 SSA counties. They found weaker associations between women’s autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services in SSA than in other parts of the world. For example, the pooled aORs for autonomy and ≥4 ANC was 1.52 for all 31 countries and 1.29 in the 21 SSA countries.51 Note that we used slightly different DHS measures of autonomy to Ahmed et al. We used women’s attitudes to violence as well as women’s participation in decisions (finance and major household purchases), while Ahmed et al only examined women’s autonomy about decisions. The paper by Ahmed et al51 was published in 2010 so they used older DHS data than we did.

Basedmainly on studies in Asia, women’s autonomy is considered a crucial contributor to their utilisation of maternal healthcare services. For example, women’s autonomy has consistently been shown to be associated with the utilisation of ANC and SBA in southern and northern India,9 14 in Nepal and Indonesia where women’s financial autonomy has been found to be associated with their utilisation of maternal healthcare service.22 23

Three measures of women’s autonomy were relatively strongly related to the use of maternal healthcare services in the Southern African region. Women who made decisions on household income, opposed sexual violence and who made decisions on major household purchases were nearly 50% more likely to use both ≥4 ANC and SBA.

Weaker associations in other African regions are unlikely to be explained by differences in women’s education or household wealth, as we adjusted for these variables. The explanation is probably related to differences in economic development and culture across countries in SSA.51–53 A qualitative study in Zambia found that factors leading to delivery at home rather than at a clinic included: lack of female autonomy, the influence of husbands and parents, perceived low quality of clinic-based services and positive attitudes towards traditional birth attendants.28 Jayachandran showed that the level of female autonomy tended to be higher in countries with higher gross domestic product per capita.53 Economic development is also associated with better education for men and women and higher quality health services.

One unexpected finding in our study is that women with higher autonomy on some measures in Chad, Mali and Senegal were less likely to use either ≥4 ANC or SBA than women with less autonomy. These results are consistent with some previous research in Malawi and Mali.25 54 In a study in Malawi, it was found that women with higher autonomy were less likely to be accompanied by their male partners to ANC services.25 In Mali, Upadhyay and colleagues found that women who had higher autonomy towards sexual violence tended to have more children, perhaps because higher fertility is regarded as a sign of autonomy.54 55 Another explanation for the inverse associations that we observed might be that more empowered women in Chad, Mali and Senegal might be more likely to successfully refuse to use maternal healthcare services that they perceive to be inadequate.56–60

The strengths of our study are that we used nationally representative DHS surveys from countries across SSA in addition to utilisation of four separate measures of female autonomy. One of the limitations is that DHS surveys are cross-sectional studies where autonomy is measured after the relevant pregnancy has occurred. Longitudinal studies measuring women’s autonomy before pregnancy and then following women through to the end of the pregnancy, assessing utilisation of maternal healthcare services, would provide higher quality evidence about the causal relationship between autonomy and ≥4 ANC and SBA. Also, we did not study as separate variables the four recommended ANC timings—first visit 8–12 weeks, second visit 24–26 weeks, third visit 32 weeks and the fourth visit 36–38 weeks.5 Another limitation is the measurement of autonomy. Despite many definitions and measures of women’s autonomy, no measure can capture its true complex meaning.10 19 22 24 46 Women’s autonomy remains a multifaceted concept which varies between cultures and societies, even within the same country.8 54 Poor measurements of autonomy may explain why we found such weak associations between autonomy and use of maternal healthcare services. The DHS provides useful indicators of autonomy for comparison across countries, but further in-depth research into cultural differences concerning the meaning of autonomy is needed for a better understanding of women’s autonomy and its association with maternal healthcare.

Conclusion

The overall goal of this study was to examine the association between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services—≥4 ANC visits and delivery by SBA—across 31 SSA countries. We found weak associations at both regional and country level. The exception was the Southern Africa region where associations between women’s autonomy and the utilisation of maternal healthcare services were reasonably strong. Further research on women’s autonomy is needed in SSA to inform gender and health policies concerning utilisation of maternal healthcare services. Moreover, additional research is required into the inverse associations between some countries where women with higher autonomy on some measures were less likely to use maternal healthcare services.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The concept was initiated by CC, who also collected the data, produced the tables, figures and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the study design and review of the manuscript with vital input from KEA and RGC. KEA contributed significantly to the statistical analyses. JN provided critical contributions to the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study is based on publicly available DHS data. CC was granted access to the data by the MEASURE DHS/ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data used in this study are freely accessible to the public at the DHS website https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. . Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2016;387:462–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, et al. . Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:980–1004. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Maternal mortality at the end of a decade: signs of progress? Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:561–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. UNFPA. Maternal health thematic fund annual report 2014: Surging towards the 2015 deadline. Washington DC: UNFPA, 2015. http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MHTF%20annual%20report%20for%20WEB_0.pdf (accessed 11 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO. Antenatal care. Geneva: WHO int, 2016. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/publications/aonsectionIII_2.pdf (accessed 7 July 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alam N, Hajizadeh M, Dumont A, et al. . Inequalities in maternal health care utilization in sub-Saharan African countries: a multiyear and multi-country analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120922 10.1371/journal.pone.0120922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ronsmans C, Etard JF, Walraven G, et al. . Maternal mortality and access to obstetric services in West Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2003;8:940–8. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kishor S, Subaiya L. Understanding womens empowerment: a comparative analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data. Maryland: Macro International, 2008. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR20/CR20.pdf (accessed 10 June 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mistry R, Galal O, Lu M. “Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: a contextual analysis”. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:926–33. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woldemicael G. Do women with higher autonomy seek more maternal health care? Evidence from Eritrea and Ethiopia. Health Care Women Int 2010;31:599–620. 10.1080/07399331003599555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haque M, Islam TM, Tareque MI, et al. . Women empowerment or autonomy: A comparative view in Bangladesh context. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 2011;8:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oppenheim Mason K. The impact of women’s social position on fertility in developing countries. Sociol Forum 1987;2:718–45. 10.1007/BF01124382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bott S, Jejeebhoy SJ. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in South Asia: an overview of findings from the 2000 Mumbai conference. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bloom SS, Wypij D, Das Gupta M. Dimensions of women’s autonomy and the influence on maternal health care utilization in a north Indian city. Demography 2001;38:67–78. 10.1353/dem.2001.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kabeer N. Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment Discussing Women’s Empowerment-Theory and Practice. Stockholm: Sida Studies No. 3. Novum Grafiska AB, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malhotra A, Shuler S, Boender C. Measuring women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. Washington DC: Work Bank, 2002. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGENDER/Resources/MalhotraSchulerBoender.pdf (accessed 28 April 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dyson T, Moore M. On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Popul Dev Rev 1983;9:35–60. 10.2307/1972894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Basu AM. Culture, the status of women and demographic behaviour: illustrated with the case of India. London: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kabeer N, McFadden P, Arnfred S, et al. . Discussing women’s empowerment - theory and practice. Stockholm: Sida Studies No3, 2001. http://www.sida.se/contentassets/51142018c739462db123fc0ad6383c4d/discussing-womens-empowerment-theory-and-practice_1626.pdf (accessed 17 Sep 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jejeebhoy SJ, Sathar ZA. Women’s Autonomy in India and Pakistan: The Influence of Religion and Region. Popul Dev Rev 2001;27:687–712. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00687.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mason KO, Smith HL. Husbands’ versus wives’ fertility goals and use of contraception: the influence of gender context in five Asian countries. Demography 2000;37:299–311. 10.2307/2648043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Furuta M, Salway S. Women’s position within the household as a determinant of maternal health care use in Nepal. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2006;32:017–27. 10.1363/3201706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beegle K, Frankenberg E, Thomas D. Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal and delivery care in Indonesia. Stud Fam Plann 2001;32:130–46. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shimamoto K, Gipson JD. The relationship of women’s status and empowerment with skilled birth attendant use in Senegal and Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:154 10.1186/s12884-015-0591-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jennings L, Na M, Cherewick M, et al. . Women’s empowerment and male involvement in antenatal care: analyses of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in selected African countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:297 10.1186/1471-2393-14-297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fotso JC, Ezeh AC, Essendi H. Maternal health in resource-poor urban settings: how does women’s autonomy influence the utilization of obstetric care services? Reprod Health 2009;6:9 10.1186/1742-4755-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osamor PE, Grady C. Women’s autonomy in health care decision-making in developing countries: a synthesis of the literature. Int J Womens Health 2016;8:191 10.2147/IJWH.S105483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sialubanje C, Massar K, Hamer DH, et al. . Reasons for home delivery and use of traditional birth attendants in rural Zambia: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:216 10.1186/s12884-015-0652-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DHS Program. Data collection. https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/data-collection.cfm (accessed 29 Sep 2018).

- 30. Rutstein SO, Rojas G. Guide to DHS statistics. Maryland: Macro International, 2006. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacy778.pdf (accessed 29 July 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Graham WJ, Bell JS, Bullough CH. Can skilled attendance at delivery reduce maternal mortality in developing countries? Studies Health Serv Organ Policy 2001;17:97–130. [Google Scholar]

- 32. García-Moreno C. Responding to sexual violence in conflict. Lancet 2014;383:2023–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60963-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. United Nations. Women Spotlight on Sustainable Development Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. 2017. http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/multimedia/2017/7/infographic-spotlight-on-sdg-5 (accessed 10 Sep 2017).

- 34. United Nations Population Information Network. UN Population Division, and UNFPA. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), 1994. http://www.un.org/popin/icpd/conference/offeng/poa.html (accessed 10 Sep 2017).

- 35. Corroon M, Speizer IS, Fotso JC, et al. . The role of gender empowerment on reproductive health outcomes in urban Nigeria. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:307–15. 10.1007/s10995-013-1266-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Horn R, Puffer ES, Roesch E, et al. . Women’s perceptions of effects of war on intimate partner violence and gender roles in two post-conflict West African Countries: consequences and unexpected opportunities. Confl Health 2014;8:12 10.1186/1752-1505-8-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hatcher AM, Woollett N, Pallitto CC, et al. . Bidirectional links between HIV and intimate partner violence in pregnancy: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:19233 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flach C, Leese M, Heron J, et al. . Antenatal domestic violence, maternal mental health and subsequent child behaviour: a cohort study. BJOG 2011;118:1383–91. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joharifard S, Rulisa S, Niyonkuru F, et al. . Prevalence and predictors of giving birth in health facilities in Bugesera District, Rwanda. BMC Public Health 2012;12:1049 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nigatu D, Gebremariam A, Abera M, et al. . Factors associated with women’s autonomy regarding maternal and child health care utilization in Bale Zone: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2014;14:79 10.1186/1472-6874-14-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamiya Y. Women’s autonomy and reproductive health care utilisation: empirical evidence from Tajikistan. Health Policy 2011;102:304–13. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sambo LG, Kirigia JM, Ki-Zerbo G. Perceptions and viewpoints on proceedings of the fifteenth assembly of heads of state and government of the African Union debate on maternal, newborn and child health and development, 25-27 July 2010, Kampala, Uganda. BMC Proc 2011;5:S1 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S5-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zakane SA, Gustafsson LL, Tomson G, et al. . Guidelines for maternal and neonatal “point of care”: needs of and attitudes towards a computerized clinical decision support system in rural Burkina Faso. Int J Med Inform 2014;83:459–69. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crowe S, Utley M, Costello A, et al. . How many births in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will not be attended by a skilled birth attendant between 2011 and 2015? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:4 10.1186/1471-2393-12-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kalule-Sabiti I, Amoateng AY, Ngake M. The effect of socio-demographic factors on the utilization of maternal health care services in Uganda. Afr Pop Stud 2014;28:515–25. 10.11564/28-1-504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:34 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Singh K, Bloom S, Haney E, et al. . Gender equality and childbirth in a health facility: Nigeria and MDG5. Afr J Reprod Health 2012;16:122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chi PC, Bulage P, Urdal H, et al. . A qualitative study exploring the determinants of maternal health service uptake in post-conflict Burundi and Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:18 10.1186/s12884-015-0449-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. Texas: STATA press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, et al. . Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One 2010;5:e11190 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Obeidat RF. How Can Women in Developing Countries Make Autonomous Health Care Decisions? Womens Health International 2016;2:116116 10.19104/whi.2016.116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jayachandran S. The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Economics 2015;7:63–88. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Upadhyay UD, Karasek D. Women’s empowerment and ideal family size: an examination of DHS empowerment measures in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2012;38:078–89. 10.1363/3807812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dyer SJ. The value of children in African countries: insights from studies on infertility. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2007;28:69–77. 10.1080/01674820701409959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chol C, Hunter C, Debru B, et al. . Stakeholders’ perspectives on facilitators of and barriers to the utilisation of and access to maternal health services in Eritrea: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:35 10.1186/s12884-018-1665-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Miller S, Cordero M, Coleman AL, et al. . Quality of care in institutionalized deliveries: the paradox of the Dominican Republic. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;82:89–103. 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00148-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas TN, Gausman J, Lattof SR, et al. . Improved maternal health since the ICPD: 20 years of progress. Contraception 2014;90(6 Suppl):S32–8. 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. More NS, Bapat U, Das S, et al. . Community mobilization in Mumbai slums to improve perinatal care and outcomes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001257 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kruk ME, Leslie HH, Verguet S, et al. . Quality of basic maternal care functions in health facilities of five African countries: an analysis of national health system surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e845–e855. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30180-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.