Abstract

Background

Polyploidization is a common event in the evolutionary history of angiosperms, and there will be some changes in the genomes of plants other than a simple genomic doubling after polyploidization. Allotetraploid Brassica napus and its diploid progenitors (B. rapa and B. oleracea) are a good group for studying the problems associated with polyploidization. On the other hand, the EIN3/EIL gene family is an important gene family in plants, all members of which are key genes in the ethylene signaling pathway. Until now, the EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus and its diploid progenitors have been largely unknown, so it is necessary to comprehensively identify and analyze this gene family.

Results

In this study, 13, 7 and 7 EIN3/EIL genes were identified in B. napus (2n = 4x = 38, AnCn), B. rapa (2n = 2x = 20, Ar) and B. oleracea (2n = 2x = 18, Co). All of the identified EIN3/EIL proteins were divided into 3 clades and further divided into 8 sub-clades. Ka/Ks analysis showed that all identified EIN3/EIL genes underwent purifying selection after the duplication events. Moreover, gene structure analysis showed that some EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus acquired introns during polyploidization, and homolog expression bias analysis showed that B. napus was biased towards its diploid progenitor B. rapa. The promoters of the EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus contained more cis-acting elements, which were mainly involved in endosperm gene expression and light responsiveness, than its diploid progenitors. Thus, B. napus might have potential advantages in some biological aspects.

Conclusions

The results indicated allotetraploid B. napus might have potential advantages in some biological aspects. Moreover, our results can increase the understanding of the evolution of the EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus, and provided more reference for future research about polyploidization.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12870-019-1716-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: EIN3/EIL gene family, Cis-element, Introns, Allotetraploid, Brassica napus, Polyploidization

Background

Polyploidization is widely recognized as an important mechanism for the formation of species in angiosperms [1–4]. Newly formed polyploids might experience rapid homolog loss, the alteration of gene expression patterns, genome restructuring post-polyploidization and other changes [5], which might vary greatly in different polyploids [6]. In addition, some gene families will also undergo changes during polyploidization, such as expansion of the gene family [7].

The ethylene-insensitive 3 (EIN3)/ethylene-insensitive 3-like (EIL) gene family is a small transcription factor gene family in higher plants [8, 9]. The EIN3/EIL genes participate in ethylene signal transduction by activating downstream ethylene response genes [10, 11]. Ethylene (ET), an important gaseous plant hormone, is involved in some important physiological processes that regulate the growth, development and senescence of plants [12]. In addition, ethylene can act as a signal molecule to regulate the expression of some genes [13]. Thus, the EIN3/EIL gene family plays an important role in plants. EIN3/EIL proteins are characterized by two structural features. One feature is that their N-terminal amino acid sequences are highly conserved with several significant structural features [14] and these sequences, except for the first ~ 80 amino acid residues, are also essential for the activity of proteins [15, 16]. The other feature is that their C-terminal sequences are less conserved than their N-terminal sequences. For instance, in some plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana [14] and mung bean [13], the poly-asparagine or poly-glutamine region widely exists in the C-terminal sequences of EIN3/EIL proteins, but such features are not found in other plants, such as tobacco [17].

The functions and characteristics of some EIN3/EIL genes have been well studied in several plants, such as A. thaliana and tobacco. EIN3 regulates the expression of its downstream gene ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1 (ERF1) and it is also involved in the transcriptional regulation initiated by ethylene in Arabidopsis [14, 15]. EIL3 (or SLIM1) functions as the central transcriptional regulator of sulfur response and metabolism in Arabidopsis [18, 19]. NtEIL2, the homolog of AtSLIM1, directly regulates the expression of some genes induced by sulfur starvation by binding to the UP9C promoter in tabacco [20]. All of the above findings have shown that EIN3/EIL proteins have a complex relationship with the ethylene and sulfur signaling pathways.

Brassica napus, a typical allotetraploid of the Brassica genus, is the third largest oil crop planted worldwide. B. napus (2n = 4x = 38, AnCn) was formed ~ 7500 years ago by natural hybridization and polyploidization of B. rapa (2n = 20, Ar) and B. oleracea (2n = 18, Co). In recent years, the whole genomes of B. rapa (Chiifu-401-42), B. oleracea (capitata-02-12) and B. napus (Darmor-bzh) have been sequenced and assembled [21–23]. The purpose of this study was to improve our understanding of the EIN3/EIL gene family in allotetraploid B. napus and to explore the changes in this gene family during the formation of B. napus. Some methods were used in this study, including gene structure analysis, chromosomal localization analysis, phylogenetic trees analysis, synteny and duplicated genes analysis, promoter analysis and expression profiles analysis.

Results

Identification and chromosomal localization of EIN3/EIL genes

The BLASTp program in the BRAD database was used to identify EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus and its diploid progenitors (B. rapa and B. oleracea), and the query sequences were six EIN3/EIL protein sequences in A. thaliana from TAIR database. All alternative protein sequences were confirmed by CD-search in NCBI, and the domain ID was pfam04873. Finally, 7, 7 and 13 genes were identified as EIN3/EIL genes in B. rapa, B. oleracea and B. napus, respectively. These identified EIN3/EIL genes were named from BrEIL1 to BrEIL4b in B. rapa, BoEIL1 to BoEIL4b in B. oleracea and BnCEIN3 to BnAEIL4d in B. napus (Table 1). The last letter in these names represented the homologous relationship with the EIN3/EIL genes in A. thaliana, with ‘a’ meaning the highest homology, followed by ‘b’ and so on. The letters A and C, following ‘Bn’, represented the An and Cn sub-genomes, respectively, in gene names of B. napus.

Table 1.

The information of EIN3/EILs in B. napus and its diploid progenitors with their Arabidopsis orthologs

| Gene name | BRAD ID | Chromosome | Strand | Block | CDs (bp) | Orthologous gene | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Start | End | ||||||

| BrEIL1 | Bra000528 | A03 | 11,612,582 | 11,614,297 | + | I | 1716 | AT2G27050 |

| BrEIL2 | Bra002358 | A10 | 10,160,414 | 10,161,946 | – | R | 1533 | AT5G21120 |

| BrEIL3a | Bra015970 | A07 | 23,293,714 | 23,295,723 | – | E | 1764 | AT1G73730 |

| BrEIL3b | Bra003831 | A07 | 18,534,952 | 18,536,782 | + | E | 1659 | AT1G73730 |

| BrEIL3c | Bra008110 | A02 | 12,192,159 | 12,193,778 | – | E | 1620 | AT1G73730 |

| BrEIL4a | Bra028601 | A02 | 1,519,950 | 1,521,317 | + | R | 1368 | AT5G10120 |

| BrEIL4b | Bra006050 | A03 | 1,762,948 | 1,764,210 | + | R | 990 | AT5G10120 |

| BoEIL1 | Bol032895 | C06 | 5,998,916 | 6,000,631 | + | I | 1716 | AT2G27050 |

| BoEIL2a | Bol036088 | C02 | 5,947,506 | 5,949,050 | + | R | 1545 | AT5G21120 |

| BoEIL2b | Bol035762 | C09 | 29,569,796 | 29,571,388 | – | R | 1593 | AT5G21120 |

| BoEIL3a | Bol026238 | C06 | 3,515,537 | 3,517,637 | + | E | 1758 | AT1G73730 |

| BoEIL3b | Bol039991 | C06 | 33,246,791 | 33,248,491 | + | E | 1701 | AT1G73730 |

| BoEIL4a | Bol024640 | C02 | 2,716,756 | 2,718,117 | + | R | 1362 | AT5G10120 |

| BoEIL4b | Bol008759 | C03 | 1,888,488 | 1,889,829 | + | R | 1074 | AT5G10120 |

| BnCEIN3 | BnaC01g32460D | chrC01 | 31,744,455 | 31,747,102 | + | F | 1764 | AT3G20770 |

| BnCEIL1a | BnaC03g26570D | chrC03 | 15,142,985 | 15,145,564 | + | I | 1692 | AT2G27050 |

| BnAEIL1b | BnaA03g22560D | chrA03 | 10,717,296 | 10,719,627 | + | I | 1713 | AT2G27050 |

| BnAEIL2a | BnaA10g14470D | chrA10 | 11,504,970 | 11,506,502 | – | R | 1500 | AT5G21120 |

| BnCEIL2b | BnaCnng35080D | chrCnn_random | 33,278,634 | 33,280,328 | – | R | 1530 | AT5G21120 |

| BnAEIL3a | BnaA07g39030D | chrA07_random | 1,960,115 | 1,962,709 | – | E | 1764 | AT1G73730 |

| BnCEIL3b | BnaC06g34570D | chrC06 | 33,988,588 | 33,991,257 | – | E | 1758 | AT1G73730 |

| BnCEIL3c | BnaC06g23450D | chrC06 | 25,297,162 | 25,299,268 | + | E | 1698 | AT1G73730 |

| BnAEIL3d | BnaA02g16550D | chrA02 | 9,876,349 | 9,880,706 | – | E | 1749 | AT1G73730 |

| BnCEIL4a | BnaC02g00520D | chrC02 | 216,092 | 217,453 | – | R | 1362 | AT5G10120 |

| BnAEIL4b | BnaA02g00350D | chrA02 | 129,692 | 131,059 | + | R | 1368 | AT5G10120 |

| BnCEIL4c | BnaC03g04150D | chrC03 | 1,999,482 | 2,000,328 | + | R | 579 | AT5G10120 |

| BnAEIL4d | BnaA03g02810D | chrA03 | 1,359,358 | 1,360,620 | + | R | 990 | AT5G10120 |

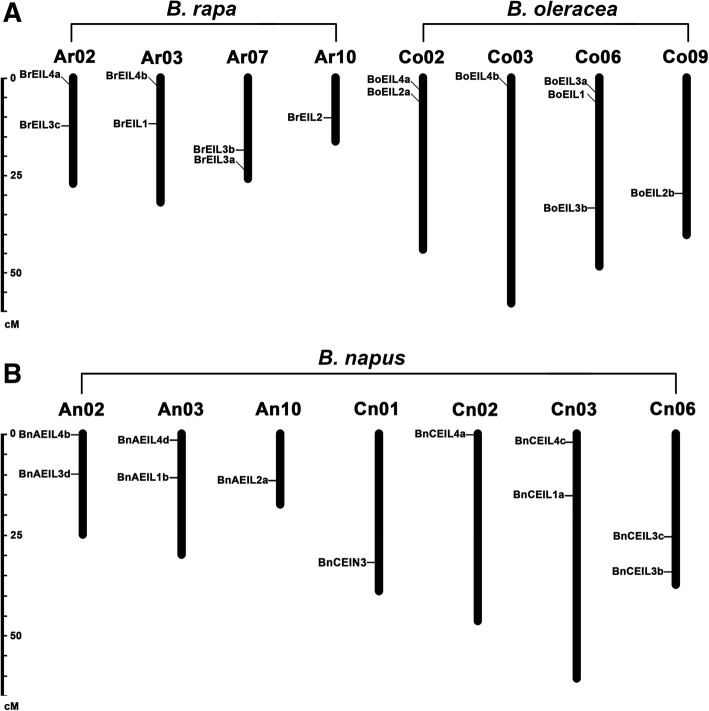

The physical locations of identified EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors were drafted to corresponding chromosomes by the MapInspector tool. Twenty-five out of twenty-seven EIN3/EIL genes could be mapped to assembled chromosomes (Fig. 1), and the other two genes (BnCEIL2b & BnAEIL3a) were located on unassembled scaffolds. Seven EIN3/EIL genes were located on four chromosomes (Ar02, Ar03, Ar07 and Ar10) in the A genome in B. rapa, only five genes were on three chromosomes (An02, An03 and An10) in the A sub-genome in B. napus. Comparing the gene distribution of the A sub-genome in B. napus with the A genome in B. rapa, the genes on the corresponding chromosomes not only were homologous genes, but they also had the same relative positions, except for the Ar07 chromosomes, two EIN3/EIL genes on which might have been lost during the formation of B. napus or due to incomplete assembly of this chromosomes. Moreover, comparing the gene distribution of the C sub-genome in B. napus with the C genome in B. oleracea, only a few EIN3/EIL genes maintained their relative positions on the corresponding chromosomes. In addition, a total of 8 homologous gene pairs (such as BrEIL4a & BnAEIL4b, BrEIL3c & BnAEIL3d) maintained their relative position on chromosomes during the formation of B. napus. Therefore, the A sub-genome of B. napus might be more stable than the C sub-genome during the process of hybridization and polyploidization.

Fig. 1.

Chromosome distribution of EIN3/EILs in B. rapa, B. oleracea (a) and B. napus (b). Genes located in unassembled scaffolds were not shown in this figure. The number of chromosomes was marked at the top of each chromosome, and the scale on the left is in megabases (Mb)

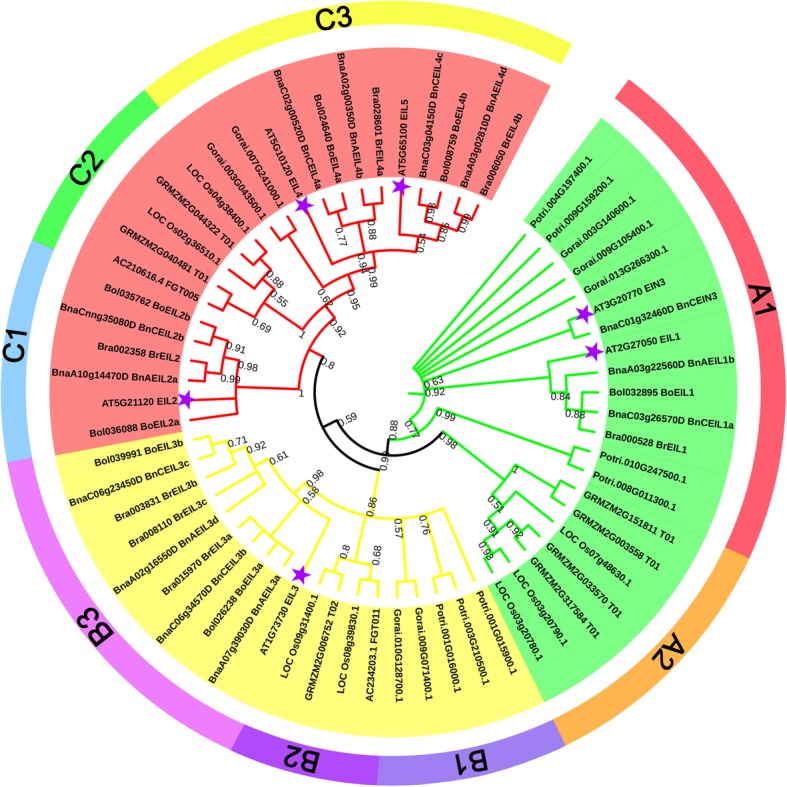

Phylogenetic analysis of EIN3/EIL proteins

A total of 63 EIN3/EIL protein sequences from 8 different species were used as reference sequences to construct the phylogenetic tree, including 6 (Arabidopsis), 7 (B. rapa), 7 (B. oleracea), 13 (B. napus), 7 (Oryza sativa), 7 (Populus trichocarpa), 7 (Gossypium raimondii) and 9 (Zea mays) members (Fig. 2). These 63 EIN3/EIL proteins were obviously divided into three clades, designated as A, B and C, which contained 8 sub-clades (A1, A2, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2 and C3). Clade A contained EIN3 and EIL1 proteins, clade B contained EIL3 proteins, and clade C consisted of EIL2, EIL4 and EIL5 proteins. The EIN3/EIL proteins in monocots and dicots were clustered in different sub-clades in this phylogenetic tree, e.g., EIN3/EIL proteins in monocots (Zea mays and Oryza sativa) were clustered in the A2, B2 and C1 sub-clades, while EIN3/EIL proteins in dicots were clustered in the remaining sub-clades. Clade A had 21 EIN3/EIL proteins, clade B had 19 proteins, and clade C had 23 proteins, so the EIN3/EIL genes were evenly classified into three clades.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of EIN3/EIL proteins in 8 species. The tree was constructed using MEGA7.0 with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The prefixes Bra, Bol, Bna, Potri, AT, LOC, GRMZM/AC, and Gorai stand for B. rapa, B. oleracea, B. napus, Populus trichocarp, Arabidopsis, Oryza sativa, Zea mays and Gossypium raimondii, respectively. The inner circle is marked in green, yellow and red representing the Clade A, Clade B, and Clade C, respectively. Each clade was divided into sub-clades, and marked in different colors on the outer circle. Only bootstrap values greater than 50% were displayed. The purple stars represented the EIN3/EIL genes in Arabidopsis

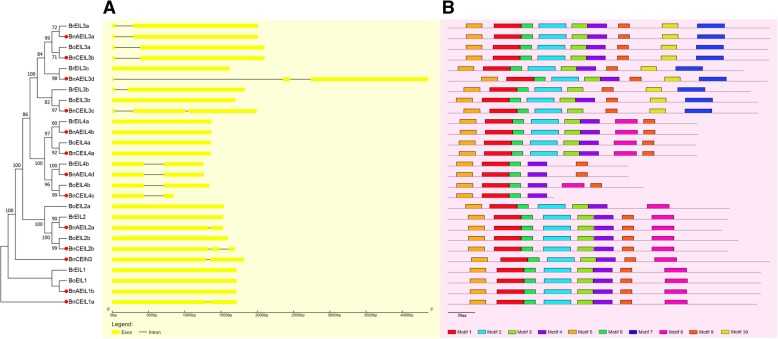

Gene structure analysis of EIN3/EIL genes

The diversity of gene structure is the main resource for the evolution of multigene families [24–26]. To explore the structural diversity of identified EIN3/EIL genes, the exon-intron structure of these genes was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 3a, twelve EIN3/EIL genes did not contain any introns, such as BrEIL3c, BoEIL3b, and BnAEIL4b. Twelve genes contained only one intron, such as BrEIL3a, BoEIL3a and BnCEIL3b, whereas the remaining three genes (BnAEIL3d, BnCEIL3c and BnCEIL2b) contained two introns. Since all genes containing two introns were genes in the allotetraploid B. napus, it was speculated that some members of the EIN3/EIL gene family acquired additional introns during the polyploidization process. To further analyze whether the gene structure of EIN3/EIL genes has altered during the process of polyploidization, 11 pairs of genes (Table 2) with the closest genetic distance were selected for further comparative analysis. Among these genes, four pairs of genes had different gene structures, and three of them had acquired two introns in the EIN3/EIL genes of the allotetraploid, such as BnAEIL3d, BnCEIL3c and BnCEIL2b, while the other pair of genes had obtained one intron (BnAEIL2a). In addition, although a pair of genes (BoEIL4b & BnCEIL4c) had an identical gene structure, BnCEIL4c apparently lost part of its second exon compared to the corresponding gene in diploid B. oleracea. These results suggest that intron/exon acquisition or loss events have happened during the evolution of the EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus, which might explain the functional divergence of the homologous EIN3/EIL genes.

Fig. 3.

Characterizations of the identified EIN3/EIL genes, including gene structure (a) and conserved motif location (b). The EIN3/EIL genes in allotetraploid B. napus were marked by the red circle

Table 2.

Information about EIN3/EIL gene pairs with potential direct evolutionary relationships

| Clade | EIN3/EIL genes in diploid progenitors | EIN3/EIL genes in allotetraploid B. napus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | The number of exons | Gene name | The number of exons | |

| A1 sub-clade | BoEIL1 | 1 | BnAEIL1b | 1 |

| B3 sub-clade | BrEIL3a | 2 | BnAEIL3a | 2 |

| BoEIL3a | 2 | BnCEIL3b | 2 | |

| BrEIL3c | 1 | BnAEIL3d | 3 | |

| BoEIL3b | 1 | BnCEIL3c | 3 | |

| C1 sub-clade | BrEIL2 | 1 | BnAEIL2a | 2 |

| BoEIL2b | 1 | BnCEIL2b | 3 | |

| C3 sub-clade | BrEIL4a | 1 | BnAEIL4b | 1 |

| BoEIL4a | 1 | BnCEIL4a | 1 | |

| BrEIL4b | 2 | BnAEIL4d | 2 | |

| BoEIL4b | 2 | BnCEIL4c | 2 | |

Next, the MEME server was used to find some conserved motifs in EIN3/EIL proteins (Fig. 3b). As a result, ten most conserved motifs were identified, in which motifs 1, 5 and 6 were present in all EIN3/EIL proteins. According to a previous study, motifs 1, 6, 3 and 4 might constitute a conserved domain of EIN3/EILs [27]. Remarkably, all proteins in clade B contained a unique motif 7, suggesting that this motif might have a special function that distinguished the function of these proteins from other EIN3/EIL proteins. Moreover, most of the closely related EIN3/EILs exhibited similar motif compositions, such as BrEIL3a & BnAEIL3a, BrEIL4a & BnAEIL4b, and BrEIL2 & BnAEIL2a, indicating the functions between them might be extremely similar.

Conserved amino acid and characteristic analysis of EIN3/EIL proteins

To further evaluate the identity of the EIN3/EIL protein sequences of B. napus and its diploid progenitors, all sequences were aligned together and similar or identical residues were shaded in different colors (Fig. 4). Different from the highly conservative N-terminal sequences of the EIN3/EIL proteins, C-terminal sequences did not show significant similarity, suggesting that these sequences were the major sources of the variations of EIN3/EIL members. The N-terminal sequences of all EIN3/EIL proteins in Arabidopsis exhibit some structural features, such as acidic N-terminal amino acids, basic amino acid clusters and a proline-rich domain [14]. In this study, four structural features were identified and refined in the EIN3/EIL proteins of B. napus and its diploid progenitors: 1) a highly acidic region (AR) at the N-terminus; 2) five conserved basic regions (BRI-V); 3) a proline-rich region (PR); and 4) a poly-Asp/Gln (Q/D) region (Fig. 4). In detail, the N-terminal AR mainly includes many Asp (D) and Glu (E) residues. Five BRs, including Arg (R), Lys (K) and His (H) residues, were scattered in the first part of the EIN3/EIL proteins. And the Pro (P) residue in the PR was very conserved except in four proteins (BrEIL4b, BnAEIL4d, BoEIL4b and BnCEIL4c). Regions rich in acidic amino acids, proline and glutamine are common transcriptional activation domains in some plants [14, 28]. Therefore, the amino acid composition of the first half of the EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its diploid progenitors demonstrated their roles in transcriptional activation.

Fig. 4.

Sequence alignment of all identified EIN3/EIL genes. Sequences were aligned by ClustalX, and identical or similar residues were shaded as colors. Red rectangle covers the structural features. AR: acidic region; BRI-V: basic region I-V; PR: proline-rich region; ploy Q/D: poly Asp/Gln region

As shown in Table 3, the length of identified EIN3/EIL proteins ranged from 192 (BnCEIL4c) to 587 (BnCEIN3 & BnAEIL3a) amino acids in B. napus. Additionally, the physical and chemical properties of all 27 EIN3/EIL proteins were analyzed online (Table 3), including molecular weight (MW), theoretical pI, instability index (II), aliphatic index and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY). The predicted MWs were between 22.17 kDa (BnCEIL4c) and 66.60 kDa (BnCEIN3) in B. napus. By calculation, the average number of amino acids in B. napus (498) was lower than that in its diploid progenitors (509), and the MW in B. napus (56.58 kDa) was also lower than that in its diploid progenitors (57.76 kDa). This indicated that members of the EIN3/EIL gene family might have lost partial amino acid sequences in B. napus during the process of polyploidization. All EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its diploid progenitors had an instability index greater than 40, indicating that they were all unstable proteins. All EIN3/EIL proteins were confirmed as hydrophilic proteins with the negative GRAVY values. Among all EIN3/EIL proteins, the shortest domain was 155 amino acids, such as in BnCEIL4c, BnAEIL4d, and the longest was 584 amino acids, such as in BrEIL3a and BnAEIL3a. The tertiary structure of all EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its diploid progenitors was predicted using the homology modeling method (SWISS-MODEL) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Results showed that the EIN3/EIL proteins mainly matched two templates. One was the three-dimensional structure of the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of AtEIN3 protein (SMTL ID: 4zds.1), which is composed of six α-helices and five short helical turns [29]. The other was the three-dimensional structure of the DBD of AtEIL3 (SMTL ID: 1wij.1), which is composed of 5 α-helices [8].

Table 3.

The predicated protein information of EIN3/EILs in B. napus and its diploid progenitors

| Gene name | No. of amino acids | Domin location | Mol. Wt (kDa) | Isoelectric point (pI) | Instability index (II) | Aliphatic index | Grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrEIL1 | 571 | 48–297 | 65.06 | 5.8 | 56.57 | 62.61 | −0.714 |

| BrEIL2 | 510 | 49–299 | 58.07 | 6.88 | 53.57 | 53.55 | −0.93 |

| BrEIL3a | 587 | 4–587 | 65.97 | 5.16 | 62.17 | 65.6 | −0.861 |

| BrEIL3b | 552 | 4–552 | 62.53 | 5.29 | 60.82 | 66.9 | −0.878 |

| BrEIL3c | 539 | 1–539 | 60.80 | 5.43 | 58.6 | 67.12 | −0.815 |

| BrEIL4a | 455 | 30–274 | 51.77 | 4.99 | 61.1 | 66.24 | −0.82 |

| BrEIL4b | 329 | 24–178 | 38.10 | 4.97 | 70.26 | 58.66 | −0.903 |

| BoEIL1 | 571 | 48–297 | 65.27 | 5.96 | 56.26 | 63.29 | −0.696 |

| BoEIL2a | 514 | 40–288 | 58.33 | 6.34 | 50.28 | 65.06 | −0.788 |

| BoEIL2b | 530 | 49–299 | 60.42 | 6.27 | 53.55 | 52.81 | −0.964 |

| BoEIL3a | 585 | 4–585 | 65.73 | 5.2 | 62.25 | 64.82 | −0.869 |

| BoEIL3b | 566 | 1–566 | 64.23 | 5.39 | 64.92 | 65.62 | −0.924 |

| BoEIL4a | 453 | 28–272 | 51.37 | 5.02 | 56.92 | 66.31 | −0.787 |

| BoEIL4b | 357 | 24–178 | 41.05 | 4.88 | 73.27 | 58.43 | −0.89 |

| BnCEIN3 | 587 | 51–303 | 66.60 | 5.38 | 48.8 | 62.4 | −0.726 |

| BnCEIL1a | 563 | 48–297 | 64.38 | 5.73 | 56.39 | 62.98 | −0.702 |

| BnAEIL1b | 570 | 48–297 | 64.98 | 5.92 | 54.21 | 62.72 | −0.716 |

| BnAEIL2a | 499 | 49–299 | 56.78 | 6.88 | 53.22 | 53.95 | −0.911 |

| BnCEIL2b | 509 | 49–299 | 57.92 | 6.22 | 52.47 | 53.28 | −0.942 |

| BnAEIL3a | 587 | 4–587 | 66.04 | 5.16 | 61.39 | 64.28 | −0.874 |

| BnCEIL3b | 585 | 4–585 | 65.73 | 5.2 | 62.25 | 64.82 | −0.869 |

| BnCEIL3c | 565 | 4–565 | 63.90 | 5.25 | 62.55 | 66.94 | −0.889 |

| BnAEIL3d | 582 | 34–582 | 65.87 | 5.46 | 55.32 | 69.19 | −0.744 |

| BnCEIL4a | 453 | 28–272 | 51.41 | 4.98 | 58.22 | 66.11 | −0.786 |

| BnAEIL4b | 455 | 30–274 | 51.72 | 5.02 | 61.53 | 66.02 | −0.821 |

| BnCEIL4c | 192 | 24–178 | 22.17 | 8.75 | 79.13 | 76.72 | −0.769 |

| BnAEIL4d | 329 | 24–178 | 38.10 | 4.97 | 70.26 | 58.66 | −0.903 |

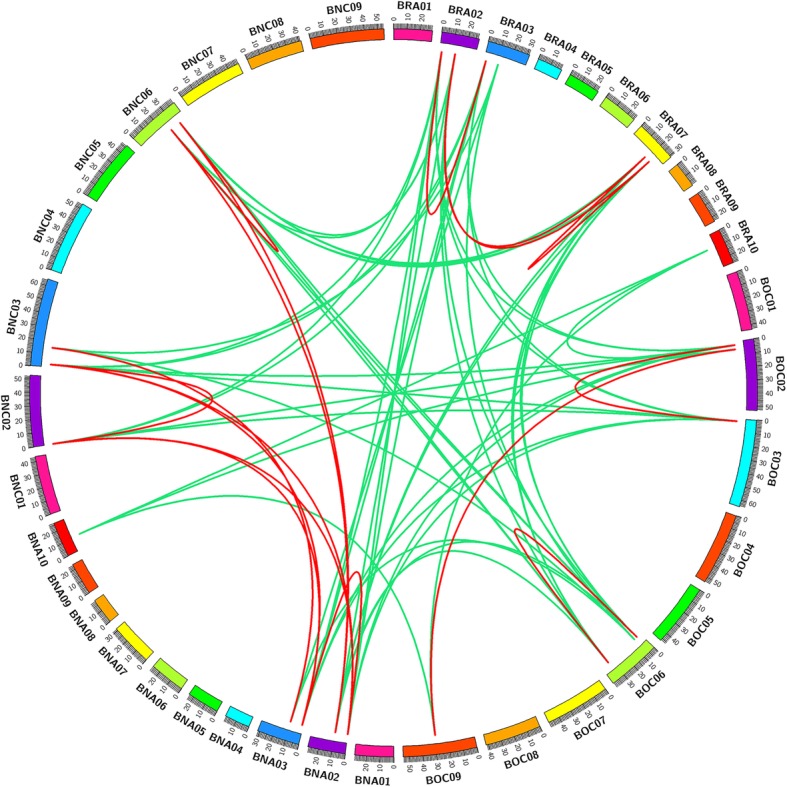

Synteny and duplicated gene analysis of EIN3/EIL genes

The synteny relationship of EIN3/EIL genes was analyzed using the genome information from B. napus (An and Cn) and its diploid progenitors (Ar and Co) with the syntenic information from the BRAD database. A total of 17 pairs of EIN3/EIL syntenic paralogs and 51 pairs of syntenic orthologs were found in these genomes (Fig. 5). Ten pairs of syntenic paralogs were observed in B. napus, and each pair of syntenic EIN3/EIL genes corresponded to a homologous gene in Arabidopsis. For example, a pair of syntenic paralogs (BnCEIL1a and BnAEIL1b) were located on Cn03 and An03 chromosomes, respectively, and all of them exhibited high sequence similarities with AtEIL1 (AT2G27050). Moreover, compared with the number of syntenic orthologous EIN3/EIL genes of B. rapa and B. oleracea, 20 orthologous genes were observed between B. rapa and B. napus, and 18 between B. oleracea and B. napus. In addition, 13 pairs of syntenic orthologous genes were found in B. rapa and B. oleracea, only 7 pairs were found in the two sub-genomes of B. napus, indicating that some of the syntenic EIN3/EIL genes might be lost during the process of polyploidization.

Fig. 5.

Genome-wide synteny analysis for EIN3/EIL genes among B. napus and its diploid progenitors. BRA01–10 and BOC01–09 represented chromosomes in B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively. BNA01–10 and BNC01–09 represented chromosomes in the An and Cn sub-genomes in B. napus, respectively. All identified EIN3/EIL genes were mapped onto corresponding chromosomes. Green lines linked the syntenic orthologs and red lines linked the syntenic paralogs

Most duplicated genes have been silenced for millions of years, with only a few surviving and further undergoing intense purifying selection after duplication events [30]. To obtain more insight into whether selective pressure was associated with the EIN3/EIL genes after duplication events, the non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous substitution (Ks) values were calculated for the 10 identified duplicated gene pairs (Table 4). According to the ratio of Ka and Ks, the selection pressure for duplicated genes can be presumed. The value of Ka/Ks = 1 indicates that genes were undergoing neutral selection, Ka/Ks > 1 means that genes were selected positively, and Ka/Ks < 1 shows that genes undergoing purifying selection [31]. As shown in Table 4, the Ka/Ks values from all 10 gene pairs were less than 1, indicating that the EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus and its diploid progenitors has undergone purifying selection pressure after the duplication events.

Table 4.

The Ka and Ks values of duplicated EIN3/EIL gene pairs

| Duplicated gene pairs | Ks | Ka | Ka/Ks | Duplication type | Types of selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrEIL3a-BrEIL3c | 0.449 | 0.082 | 0.183 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BrEIL3a-BrEIL3b | 0.397 | 0.076 | 0.192 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BoEIL3a-BoEIL3b | 0.435 | 0.071 | 0.163 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnCEIL1a-BnAEIL1b | 0.072 | 0.015 | 0.215 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnAEIL2a-BnCEIL2b | 0.074 | 0.019 | 0.260 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnAEIL3a-BnCEIL3b | 0.118 | 0.015 | 0.130 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnAEIL3a-BnCEIL3c | 0.396 | 0.077 | 0.193 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnCEIL3b-BnCEIL3c | 0.441 | 0.076 | 0.173 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnCEIL3c-BnAEIL3d | 0.441 | 0.102 | 0.232 | Segmental | Purify selection |

| BnCEIL4a-BnAEIL4b | 0.137 | 0.012 | 0.089 | Segmental | Purify selection |

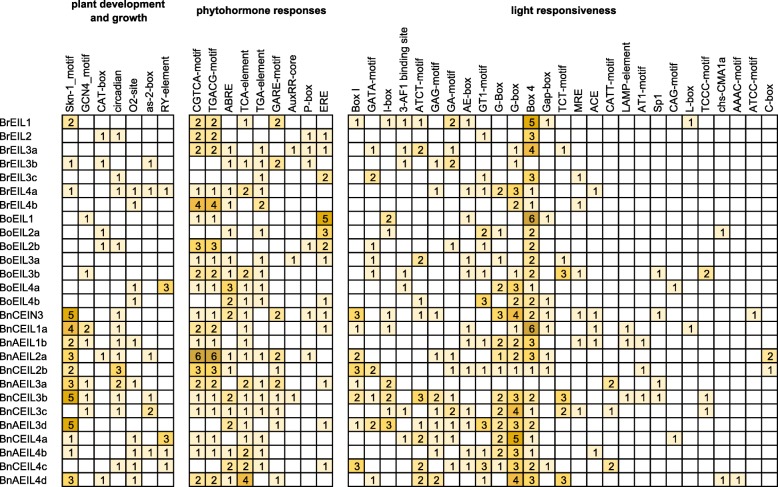

Analysis of cis-acting elements in the promoters of EIN3/EIL genes

The presence of different cis-acting elements in promoters of genes might imply that the functions of these genes were different. To explore the cis-acting elements in the promoters of EIN3/EIL genes, a 1.5 kb genomic sequence upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) in each gene was extracted and then searched in the PlantCARE database [32]. As shown in Fig. 6, the cis-acting elements responsible for plant development and growth, phytohormone responses and light responsiveness in the promoters of all EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors were identified and counted. Seven cis-acting elements were associated with plant development and growth and two of them (Skn-1_motif and GCN4_motif) [33] were involved in endosperm gene expression. Most (84.6%) promoters of EIN3/EIL genes contained a Skn-1_motif in the allotetraploid B. napus, while few promoters of EIN3/EIL genes contained Skn-1_motif in the diploid B. rapa and B. oleracea. CAT-box [34], a cis-acting regulatory element related to meristem expression, were found in some EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors. The circadian control element, circadian [35], was also found in many promoters of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus, such as BnCEIL2b and BnAEIL3a. The remaining cis-acting elements associated with plant development and growth were zein metabolism regulatory elements (O2-site) and the as-2-box and RY-element [36], which are specific for shoot and seed development.

Fig. 6.

Cis-acting elements on promoters of all identified EIN3/EIL genes

For phytohormone response-related cis-acting regulatory elements, CGTCA-motif and TGACG-motif [37] involved in the MeJA-responsiveness were identified at the EIN3/EIL gene promoters in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors. Auxin-responsive elements (TGA-element and AuxRR-core) [38] and gibberellin-responsive elements (GARE-motif and P-box) [39] were also found in some EIN3/EIL gene promoters. ABRE [40] and TCA-element, which are related to the abscisic acid and salicylic acid responsiveness, respectively, were found in most EIN3/EIL gene promoters. ERE, an ethylene-responsive element, was also present in some EIN3/EIL gene promoters. Moreover, BoEIL1 had the largest number (5) of EREs in its promoter. A total of 27 elements were associated with light responsiveness in the promoters of all identified EIN3/EIL genes, such as Box 4, G-box and GT1-motif. It was worth noting that most of the cis-regulatory elements observed in the identified EIN3/EIL gene promoters in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors were primarily associated with light responsiveness.

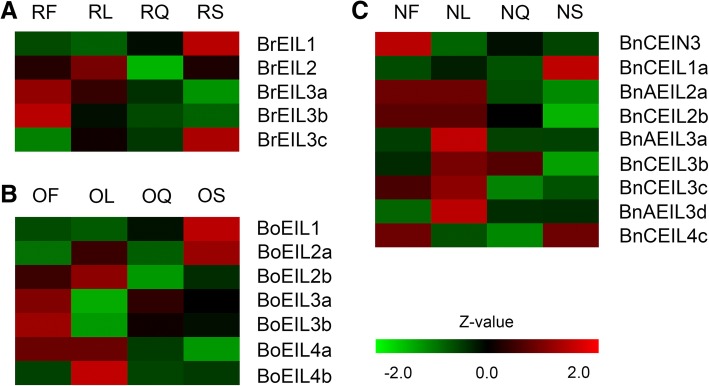

Gene expression pattern analysis of EIN3/EIL genes

To further understand the expression of all identified EIN3/EIL genes and their potential biological functions, their expression patterns in four major tissues (leaves, stems, flowers and siliques) were investigated based on our RNA-seq data (Additional file 2: Table S1). Overall, the expression of all EIN3/EIL genes were not tissue-specific in these four tissues, indicating that they might play roles in all these tissues (Fig. 7). As shown in Additional file 2: Table S1, a total of 6 EIN3/EIL genes were not expressed in selected tissues. Among them, BrEIL4a and BrEIL4b were not expressed in all four tissues in B. rapa, and 4 genes (BnAEIL1b, BnCEIL4a, BnAEIL4b and BnAEIL4d) were not expressed in B. napus. As seen in Fig. 7, homologous genes of EIL1 showed markedly high expression in stems of both B. napus and its two diploid progenitors. Furthermore, the homologous genes of EIL3 had relatively high expression levels in leaves of B. napus, but expressed lower in its two diploid progenitors, which indicated that EIL3 might play a more important role in leaves of B. napus after hybridization and polyploidization.

Fig. 7.

Expression patterns of identified EIN3/EILs in stems, leaves, flowers and siliques. a The expression patterns of EIN3/EILs in B. rapa. b The expression patterns of EIN3/EILs in B. oleracea. c The expression patterns of EIN3/EILs in B. napus

To investigate whether the expression patterns of all EIN3/EIL genes in four tissues changed in the allotetraploid B. napus and its two diploid progenitors during evolutionary process, the previously mentioned eleven gene pairs (Table 2) that might have an evolutionary relationship were analyzed for their expression patterns. The FPKM (fragments per kilobase million) values of these gene pairs were shown in Table 5. By comparison, the gene pairs in the C3 sub-clade were highly conserved both in terms of gene structure and gene expression pattern. Specifically, all four gene pairs in the C3 sub-clade had the same gene structure, and the expression patterns of the three gene pairs were consistent. Moreover, there was a gene pair (BoEIL1 and BnAEIL1b) that changed greatly in expression pattern. BoEIL1 was highly expressed in all four tissues in B. oleracea, but BnAEIL1b was not expressed in the four tissues in B. napus. This suggested that this gene might have undergone functional changes during the process of polyploidization. There was also a significant change in the expression of BrEIL3a and BnAEIL3a in leaves. BrEIL3a was highly expressed in leaves of B. oleracea, but BnAEIL3a was not expressed in leaves of B. napus, indicating that this gene no longer plays an important role in the leaves of B. napus.

Table 5.

The expression patterns of EIN3/EIL gene pairs with potential direct evolutionary relationships

| Clade | Gene pairs with evolutionary relationship | Flowers_FPKM | Leaves_FPKM | Siliques_FPKM | Stems_FPKM | Gene structurea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 sub-clade | BoEIL1 | 28.80 | 27.85 | 32.86 | 50.47 | S |

| BnAEIL1b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| B3 sub-clade | BrEIL3a | 11.38 | 9.53 | 7.79 | 6.19 | S |

| BnAEIL3a | 5.37 | 0.00 | 4.87 | 5.02 | ||

| BoEIL3a | 19.85 | 8.06 | 15.98 | 14.05 | S | |

| BnCEIL3b | 5.36 | 5.62 | 5.56 | 5.16 | ||

| BrEIL3c | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0 | D | |

| BnAEIL3d | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.47 | ||

| BoEIL3b | 9.75 | 3.84 | 6.78 | 6.23 | D | |

| BnCEIL3c | 3.74 | 4.39 | 1.93 | 2.38 | ||

| C1 sub-clade | BrEIL2 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.12 | D |

| BnAEIL2a | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.16 | ||

| BoEIL2b | 0.02 | 0 | 1.30 | 0.06 | D | |

| BnCEIL2b | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.15 | ||

| C3 sub-clade | BrEIL4a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | S |

| BnAEIL4b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| BoEIL4a | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.05 | S | |

| BnCEIL4a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| BrEIL4b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | S | |

| BnAEIL4d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| BoEIL4b | 0.76 | 0.13 | 1.11 | 0.67 | S | |

| BnCEIL4c | 0 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0 |

aGene structure was used to show whether the gene pairs had the same intron/exon structure. S represented they have same gene structure and D represented they have different gene structure

To further explore the bias in expression of EIN3/EIL genes in the four tissues of the allotetraploid B. napus, we analyzed the expression of EIL2, EIL3 and EIL4 based on FPKM values. An interesting phenomenon was that the expression of these three genes was biased towards the diploid progenitor B. rapa in all four tissues of B. napus.

Discussion

Polyploidization is a common event in the evolutionary history of various species [41], and polyploidy is prevalent in plants, especially in angiosperms [42]. After polyploidization, plants obtain more than one set of genomes with a series of genomic changes other than a simple addition. The group of B. napus and its diploid progenitors (B. rapa and B. oleracea) is applicable for studying the polyploidization. Moreover, the EIN3/EIL gene family is an important gene family and EIN3/EIL genes affect the growth and development of plants by participating in the ethylene signal transduction process [10, 11]. Previous studies on the EIN3/EIL gene family have been conducted in poplar and Rosaceae plants [27, 43], whereas there have been no reports on this family in Brassica. Therefore, we identified and analyzed the EIN3/EIL gene family in the allotetraploid B. napus and its diploid progenitors to insight into the evolution of this gene family during the natural formation of B. napus.

EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus acquired introns during polyploidization

Introns are non-coding sequences that interrupt the coding regions of genes in eukaryotes. Moreover, introns are prominent markers of eukaryotic protein-coding genes [44–46] and are critical components for genome adaptation to environmental challenges [47]. In this study, some EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus acquired introns. Statistical analysis showed that only one (EIL3) of the six (16.7%) EIN3/EIL genes in Arabidopsis contained an intron, and the remaining five genes had no introns. 42.9 and 28.6% of EIN3/EIL genes contained introns in B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively. However, up to 77% of the EIN3/EIL genes contained introns in B. napus, which might bring some benefits to B. napus. Introns may retain mutational disturbances, thereby buffering the coding exons from mutations and protecting exons to make genes more conserved in evolution [48, 49]. Moreover, the presence of introns has some distinct advantages for organisms [48, 50]. First, introns can increase protein diversity by alternative splicing or exon shunting [51–53]. Second, introns can regulate gene expression [52], and some introns named intron-mediated enhancement (IME) can also promote gene expression [54]. Third, introns can produce non-coding RNAs to participate in some regulatory processes [55]. In addition, introns can increase the function of proteins by obtaining functional domains, thereby increasing the versatility of proteins [49]. Finally, introns play key roles in some biological processes, such as transcriptional coupling, splicing and mRNA export [56]. Of course, the relatively large number of introns in the EIN3/EIL gene family of B. napus might bring these advantages to the organism, but this hypothesis needs further study.

Homolog expression of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus is biased towards its diploid progenitor B. rapa

B. napus, a young allotetraploid, formed only ~ 7500 years ago by the natural hybridization and polyploidization of B. rapa and B. oleracea [22]. Whole-genome sequencing of B. napus and its diploid progenitors also provided us with a valuable opportunity to explore how the gene families or sub-genomes were affected in young polyploids. In the current study, there was no large-scale gene loss in the EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus. Lower gene loss rates are generally thought to promote the wide spread of polyploids in the early stages of their formation and contribute to their fast diversification [23, 42, 57, 58]. In fact, the chromosomal DNA and gene loss rate can reach 15% during the first generation of some artificial/synthetic tetraploids [59, 60].

The homolog expression of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus was biased towards its diploid progenitor B. rapa. On the one hand, the distribution of EIN3/EIL genes on the A genome in B. rapa and the A sub-genome in B. napus was identical, except for the Ar07-An07 chromosomes (Fig. 1). Only a few EIN3/EIL genes maintained their number and relative position on the C genome in B. oleracea and the C sub-genome in B. napus. On the other hand, the expression bias analysis showed that all three genes that could be analyzed (EIL2, EIL3 and EIL4) were biased towards B. rapa in the four tissues (leaves, stems, flowers and siliques).

The promoter of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus contains more cis-acting elements than its diploid progenitors

Cis-acting elements of the gene promoter regions control the gene responses in the organism and constitute the basic functional link between the complex regulatory networks of genes [61]. Cis-acting elements involve extensive biological functions, such as plant growth and development and hormone responses. Different genes have various classes of cis-acting elements to exert different biological functions. The EIN3/EIL gene promoter region is rich in cis-acting elements in poplar, and two of them (CAAT-box and TATA-box) are present in all EIL genes [43]. These two elements are common cis-acting elements in the promoter region of eukaryotic genes, where the CAAT-box forms the binding site for RNA transcription factors and regulates the frequency of gene expression [62], and another TATA-box contains the binding site of general transcription factors or histones and involved in the transcription process along with its binding factor [63]. In this study, these two cis-acting elements were also present in all EIN3/EIL gene promoters in B. napus and its diploid progenitors. In addition, as shown in Fig. 6, the cis-acting elements of EIL3/EIL gene promoters were divided into three categories (plant development and growth, phytohormone responses and light responsiveness) according to the biological processes. Interestingly, the total number of cis-acting elements in the EIN3/EIL gene promoters of B. napus (373) was far more than the sum of the elements in its diploid progenitors (235). Further analysis revealed that the number of elements involved in the phytohormone responses in EIN3/EIL gene promoters of B. napus (99) was similar to the sum of the elements in its diploid progenitors (95). Therefore, the quantitative difference mainly exists in cis-acting elements related to plant development and growth and light responsiveness. Furthermore, the total number of cis-elements involved in plant development and growth in the EIN3/EIL promoters of B. napus was 2.9 times that in the diploid progenitors, and the number of light responsiveness elements was 1.8 times that in the diploid progenitors. Two cis-elements showed significant differences, namely skn_1 motif and Box I. Specifically, there were 34 skn_1 motifs and 16 Box I in the EIN3/EIL gene promoters of B. napus, but there were only 4 skn_1 motifs and 1 Box I in the two diploid progenitors. The skn_1 motif is a cis-acting regulatory element required for endosperm gene expression, and Box I is a light-responsive element. Therefore, the increased number of cis-elements in EIN3/EIL gene promoters of B. napus might enhance their functions in endosperm gene expression and light responsiveness.

Conclusions

In this study, 13, 7 and 7 EIN3/EIL genes were identified in allotetraploid B. napus, the An genome donor B. rapa and the Cn genome donor B. oleracea, respectively. After analysis, many members of EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus acquired introns during polyploidization, which might bring some advantages to the organism. Moreover, the EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus is biased towards its diploid progenitor B. rapa rather than B. oleracea, from the two aspects of gene localization and gene expression. In addition, the promoter of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus contains more cis-acting elements than its diploid progenitors, which might enhance their functions in endosperm gene expression and light responsiveness. In short, our results indicated allotetraploid B. napus might have potential advantages in some biological aspects, and these results can increase the understanding of the evolution of the EIN3/EIL gene family in B. napus, therefore provided more reference for future research about polyploidization.

Methods

Plant materials

The seeds of the tetraploid B. napus (cv. Darmor) and its diploid progenitors B. rapa (cv. Chiifu) and B. oleracea (cv. Jinzaosheng) were obtained from the Oil Crops Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China. These materials were grown under natural conditions in Wuhan, China, and inflorescences were bagged to prevent pollen contamination before blossom. Young leaves, inflorescence stems, blooming flowers and siliques (10DAP, Days after Pollination) of 6-months materials were simultaneously and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen for later use.

Identification of EIN3/EIL genes

The genome data of B. napus and its two diploid progenitors, B. rapa and B. oleracea, were obtained from the BRAD database (http://brassicadB.org/brad/) [64]. Six EIN3/EIL protein sequences from A. thaliana, acquired from the TAIR database (http://www.arabidopsis.org/), were used as queries to perform BLASTp searches (E-value <1e-5) with all proteins from these three species. To identify the EIN3/EIL genes in three Brassica genomes accurately, all putative protein sequences were confirmed by searching for the EIN3/EIL domain (pfam04873) using CD-search in the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd) [65]. In this study, only proteins containing the complete EIN3/EIL domain were considered EIN3/EIL proteins. Finally, the identified EIN3/EIL genes were manually named according to their homologous relationships with the EIN3/EIL genes in A. thaliana. EIN3/EILs in Oryza sativa, Zea mays, Gossypium raimondii and Populus trichocarpa were identified using the same methods as described above, and the genome data of all these species were obtained from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html).

Chromosome location and gene structure analysis

The location information of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors was collected from the BRAD database, and their physical positions were drafted to the corresponding chromosomes by the software MapInspector. The exon/intron structures of EIN3/EIL genes were analyzed using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) 2.0 (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn//index.php) [66].

Conserved motif and characteristic analysis

Conserved motifs in EIN3/EIL proteins were investigated by online MEME server (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) [67], with the max motif number as 10 and the other parameters as default values. Moreover, the physico-chemical characteristics of EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors were calculated by the online ProtParam tool of ExPASy (http://weB.expasy.org/protparam/) [68], including sequence length, molecular weight (MW), theoretical isoelectric point (pI), instability index (II), aliphatic index and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY). The tertiary structure of EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its diploid progenitors was predicted using the homology modeling method (SWISS-MODEL, https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org).

Phylogenetic relationship analysis

The EIN3/EIL protein sequences in 6 dicots (B. rapa, B. oleracea, B. napus, A. thaliana, Gossypium raimondii and Populus trichocarpa) and 2 monocots (Oryza sativa and Zea mays) were aligned using ClustalX. Subsequently, phylogenetic relationships were presumed by analyzing a Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree that was constructed by MEGA 7.0.26 [69] with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Finally, the online Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL, http://itol.embl.de/) [70] was used to decorate this phylogenetic tree.

Gene duplication and syntenic analysis

Duplicated EIN3/EIL genes were identified by BLASTn using their coding sequences (CDSs). The two criteria were (a) coverage of sequence length > 80% and (b) identity of aligned regions > 80% [71]. DnaSP software (version 5.10.01) was used to calculate the synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) substitution rates of duplicated EIN3/EIL gene pairs [72]. Then, evolutionary constraint (Ka/Ks) was calculated to analyze the selective pressure. The syntenic genes of EIN3/EILs in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors were found in the BRAD database, and Circos software was applied to express the syntenic relationship between them [73].

Promoter sequences and gene expression analysis

The promoter sequences, which were the 1500 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of the EIN3/EIL genes, were acquired from the BRAD database, and the cis-elements in the promoters were analyzed using the Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Element (PlantCARE) server (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) [32]. Plant materials were collected for transcriptome sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq X-Ten platform. To determine the expression patterns of EIN3/EIL genes in B. napus and its two diploid progenitors, RNA-seq data of four major tissues (stems, leaves, flowers and siliques) were analyzed. FPKM values were used to represent the gene expression levels. FPKM values were normalized by Z-values, and Z-values were calculated by the following formula. . The heatmap of gene expression was generated using Multi Experiment Viewer (MeV; version 4.9.0) software.

Additional files

Figure S1. The predicted tertiary structure of all EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its diploid progenitors. The predicted structure of BnCEIN3 (A). The predicted structure of BnAEIL1b, BnCEIL1a, BoEIL1 and BrEIL1 (B). The predicted structure of BnCEIL2b and BoEIL2b (C). The predicted structure of BnAEIL2a (D). The predicted structure of BoEIL2a (E). The predicted structure of BrEIL2 (F). The predicted structure of BnAEIL3d, BoEIL3b and BrEIL3c (G). The predicted structure of BnCEIL3b and BoEIL3a (H). The predicted structure of BnCEIL3c (I). The predicted structure of BrEIL3b (J). The predicted structure of BnAEIL4b, BnCEIL4a and BoEIL4a (K). The predicted structure of BnAEIL4d and BrEIL4b (L). The predicted structure of BoEIL4b (M). The predicted structure of BnAEIL3a and BrEIL3a (N). The predicted structure of BnCEIL4c (O). The predicted structure of BrEIL4a (P). (TIF 6803 kb)

Table S1. The FPKM values of identified EIN3/EIL genes in four major tissues of B. napus and its diploid progenitors (B. rapa and B. oleracea). (XLSX 15 kb)

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570539, 31370258).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article and the additional files.

Abbreviations

- A. thaliana

Arabidopsis thaliana

- AR

Acidic region

- B. napus

Brassica napus

- B. oleracea

Brassica oleracea

- B. rapa

Brassica rapa

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- BRI-V

Basic regions I-V

- DBD

DNA-binding domain

- EIN3/EIL

Ethylene-insensitive 3/ethylene-insensitive 3-like

- ERF1

ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1

- ET

Ethylene

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase million

- GRAVY

Grand average of hydropathicity

- II

Instability index

- IME

Intron-mediated enhancement

- Ka

Non-synonymous substitution

- Ks

Synonymous substitution

- ML

Maximum Likelihood

- MW

Molecular weight

- PR

Proline-rich region

- Q/D

Asp/Gln

- TSS

Transcription start site

Authors’ contributions

JW and ML conceived and designed the study. ML performed the bioinformatics analyses. ML wrote the manuscript. XW provided the experimental materials. ML, RW and ZL were responsible for planting materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mengdi Li, Email: mengdili@whu.edu.cn.

Ruihua Wang, Email: wangruihua@whu.edu.cn.

Ziwei Liang, Email: liangziwei@whu.edu.cn.

Xiaoming Wu, Email: wuxm@oilcrops.cn.

Jianbo Wang, Email: jbwang@whu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Stebbins GL., Jr Types of polyploids; their classification and significance. Adv Genet. 1947;1:403–429. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otto SP, Whitton J. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:401–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soltis PS, Soltis DE. The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:561–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayrose I, Barker MS, Otto SP. Probabilistic models of chromosome number evolution and the inference of polyploidy. Syst Biol. 2010;59:132–144. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soltis PS, Marchant DB, Van de Peer Y, Soltis DE. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;35:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soltis DE, Visger CJ, Marchant DB, Soltis PS. Polyploidy: pitfalls and paths to a paradigm. Am J Bot. 2016;103:1146–1166. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z, Gong Q, Qin W, Yang Z, Cheng Y, Lu L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of WOX genes in upland cotton and their expression pattern under different stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:113. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamasaki K, Kigawa T, Inoue M, Yamasaki T, Yabuki T, Aoki M, et al. Solution structure of the major DNA-binding domain of Arabidopsis thaliana ethylene-insensitive3-like3. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wawrzynska A, Sirko A. To control and to be controlled: understanding the Arabidopsis SLIM1 function in sulfur deficiency through comprehensive investigation of the EIL protein family. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:575. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YF, Etheridge N, Schaller GE. Ethylene signal transduction. Ann Bot. 2005;95:901–915. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Z, Zhong S, Grierson D. Recent advances in ethylene research. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:3311–3336. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abeles FB, Morgan PW, Saltveit ME., Jr . Ethylene in plant biology. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Kim WT. Molecular and biochemical characterization of VR-EILs encoding mung bean ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE proteins. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1475–1488. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao Q, Rothenberg M, Solano R, Roman G, Terzaghi W, Ecker JR. Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell. 1997;89:1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3703–3714. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. Cloning and DNA-binding properties of a tobacco Ethylene-Insensitive3 (EIN3) homolog. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:960–967. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.4.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieu I, Mariani C, Weterings K. Expression analysis of five tobacco EIN3 family members in relation to tissue-specific ethylene responses. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:2239–2244. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo H, Ecker JR. The ethylene signaling pathway: new insights. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maruyama-Nakashita A, Nakamura Y, Tohge T, Saito K, Takahashi H. Arabidopsis SLIM1 is a central transcriptional regulator of plant sulfur response and metabolism. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3235–3251. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wawrzynska A, Lewandowska M, Sirko A. Nicotiana tabacum EIL2 directly regulates expression of at least one tobacco gene induced by Sulphur starvation. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:889–900. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Wang H, Wang J, Sun R, Wu J, Liu S, et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalhoub B, Denoeud F, Liu S, Parkin IA, Tang H, Wang X, et al. Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, Liu Y, Yang X, Tong C, Edwards D, Parkin IA, et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3930. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercereau-Puijalon O, Barale JC, Bischoff E. Three multigene families in Plasmodium parasites: facts and questions. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1323–1344. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao Y, Han Y, Meng D, Li D, Jin Q, Lin Y, et al. Structural, evolutionary and functional analysis of the class III peroxidase gene family in Chinese pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1874. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellicer J, Hidalgo O, Dodsworth S, Leitch IJ. Genome size diversity and its impact on the evolution of land plants. Genes (Basel) 2018;9:88. doi: 10.3390/genes9020088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y, Han Y, Meng D, Li D, Jin Q, Lin Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis suggests high level of microsynteny and purifying selection affect the evolution of EIN3/EIL family in Rosaceae. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3400. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwechheimer C, Smith C, Bevan MW. The activities of acidic and glutamine-rich transcriptional activation domains in plant cells: design of modular transcription factors for high-level expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:195–204. doi: 10.1023/A:1005990321918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song J, Zhu C, Zhang X, Wen X, Liu L, Peng J, et al. Biochemical and structural insights into the mechanism of DNA recognition by Arabidopsis ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang J, Wang F, Hou X-L, Wang Z, Huang Z-N. Genome-wide fractionation and identification of WRKY transcription factors in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) reveals collinearity and their expression patterns under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2014;32:781–795. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0672-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lescot M, Dehais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharyya J, Chowdhury AH, Ray S, Jha JK, Das S, Gayen S, et al. Native polyubiquitin promoter of rice provides increased constitutive expression in stable transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang LF, Li WF, Han SY, Yang WH, Qi LW. cDNA cloning, genomic organization and expression analysis during somatic embryogenesis of the translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) gene from Japanese larch (Larix leptolepis) Gene. 2013;529:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson SL, Teakle GR, Martino-Catt SJ, Kay SA. Circadian clock- and phytochrome-regulated transcription is conferred by a 78 bp cis-acting domain of the Arabidopsis CAB2 promoter. Plant J. 1994;6:457–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.6040457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bobb AJ, Chern MS, Bustos MM. Conserved RY-repeats mediate transactivation of seed-specific promoters by the developmental regulator PvALF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:641–647. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.3.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rouster J, Leah R, Mundy J, Cameron-Mills V. Identification of a methyl jasmonate-responsive region in the promoter of a lipoxygenase 1 gene expressed in barley grain. Plant J. 1997;11:513–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11030513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1963–1971. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JK, Cao J, Wu R. Regulation and interaction of multiple protein factors with the proximal promoter regions of a rice high pI alpha-amylase gene. Mol Gen Genomics. 1992;232:383–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00266241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen Q, Ho TH. Functional dissection of an abscisic acid (ABA)-inducible gene reveals two independent ABA-responsive complexes each containing a G-box and a novel cis-acting element. Plant Cell. 1995;7:295–307. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgess DJ. Evolution: Polyploid gains. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:196. doi: 10.1038/nrg3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, et al. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature. 2011;473:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature09916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Filiz E, Vatansever R, Ozyigit II, Uras ME, Sen U, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of EIL gene family in woody plant representative poplar (Populus trichocarpa) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;627:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamond AI. Running rings around RNA. Nature. 1999;397:655–656. doi: 10.1038/17697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roy SW, Gilbert W. Rates of intron loss and gain: implications for early eukaryotic evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5773–5778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500383102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Trelles F, Tarrio R, Ayala FJ. Origins and evolution of spliceosomal introns. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:47–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeffares DC, Penkett CJ, Bahler J. Rapidly regulated genes are intron poor. Trends Genet. 2008;24:375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jo BS, Choi SS. Introns: the functional benefits of introns in genomes. Genomics Inform. 2015;13:112–118. doi: 10.5808/GI.2015.13.4.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukherjee D, Saha D, Acharya D, Mukherjee A, Chakraborty S, Ghosh TC. The role of introns in the conservation of the metabolic genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genomics. 2018;110:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chorev M, Carmel L. The function of introns. Front Genet. 2012;3:55. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalsotra A, Cooper TA. Functional consequences of developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:715–729. doi: 10.1038/nrg3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang YF, Zhu T, Niu DK. Association of intron loss with high mutation rate in Arabidopsis: implications for genome size evolution. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:723–733. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorlova O, Fedorov A, Logothetis C, Amos C, Gorlov I. Genes with a large intronic burden show greater evolutionary conservation on the protein level. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mascarenhas D, Mettler IJ, Pierce DA, Lowe HW. Intron-mediated enhancement of heterologous gene expression in maize. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:913–920. doi: 10.1007/BF00039430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ying SY, Lin SL. Intronic microRNAs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paterson AH, Wendel JF, Gundlach H, Guo H, Jenkins J, Jin D, et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature. 2012;492:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature11798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodhouse MR, Cheng F, Pires JC, Lisch D, Freeling M, Wang X. Origin, inheritance, and gene regulatory consequences of genome dominance in polyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5283–5288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402475111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ozkan H, Levy AA, Feldman M. Allopolyploidy-induced rapid genome evolution in the wheat (Aegilops-Triticum) group. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1735–1747. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.8.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozkan H, Levy AA, Feldman M. Rapid differentiation of homeologous chromosomes in newly-formed allopolyploid wheat. Isr J Plsnt Sci. 2002;50:S65–S76. doi: 10.1560/E282-PV55-G4XT-DRWJ. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nuruzzaman M, Sharoni AM, Satoh K, Kumar A, Leung H, Kikuchi S. Comparative transcriptome profiles of the WRKY gene family under control, hormone-treated, and drought conditions in near-isogenic rice lines reveal differential, tissue specific gene activation. J Plant Physiol. 2014;171:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laloum T, De Mita S, Gamas P, Baudin M, Niebel A. CCAAT-box binding transcription factors in plants: Y so many? Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bae SH, Han HW, Moon J. Functional analysis of the molecular interactions of TATA box-containing genes and essential genes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng F, Liu S, Wu J, Fang L, Sun S, Liu B, et al. BRAD, the genetics and genomics database for Brassica plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;5:D200–d203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu B, Jin J, Guo A-Y, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Artimo P, Jonnalagedda M, Arnold K, Baratin D, Csardi G, de Castro E, et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W597–W603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kong X, Lv W, Jiang S, Zhang D, Cai G, Pan J, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in maize. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:433. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The predicted tertiary structure of all EIN3/EIL proteins in B. napus and its diploid progenitors. The predicted structure of BnCEIN3 (A). The predicted structure of BnAEIL1b, BnCEIL1a, BoEIL1 and BrEIL1 (B). The predicted structure of BnCEIL2b and BoEIL2b (C). The predicted structure of BnAEIL2a (D). The predicted structure of BoEIL2a (E). The predicted structure of BrEIL2 (F). The predicted structure of BnAEIL3d, BoEIL3b and BrEIL3c (G). The predicted structure of BnCEIL3b and BoEIL3a (H). The predicted structure of BnCEIL3c (I). The predicted structure of BrEIL3b (J). The predicted structure of BnAEIL4b, BnCEIL4a and BoEIL4a (K). The predicted structure of BnAEIL4d and BrEIL4b (L). The predicted structure of BoEIL4b (M). The predicted structure of BnAEIL3a and BrEIL3a (N). The predicted structure of BnCEIL4c (O). The predicted structure of BrEIL4a (P). (TIF 6803 kb)

Table S1. The FPKM values of identified EIN3/EIL genes in four major tissues of B. napus and its diploid progenitors (B. rapa and B. oleracea). (XLSX 15 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article and the additional files.