Abstract

Introduction

People often experience distress following stroke due to fundamental challenges to their identity.

Objectives

To evaluate (1) the acceptability of ‘HeART of Stroke’ (HoS), a community-based arts and health group intervention, to increase psychological well-being; and (2) the feasibility of a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Design

Two-centre, 24-month, parallel-arm RCT with qualitative and economic components. Randomisation was stratified by centre and stroke severity. Participant blinding was not possible. Outcome assessment blinding was attempted.

Setting

Community.

Participants

Community-dwelling adults ≤2 years poststroke recruited via hospital clinical teams/databases or community stroke/rehabilitation teams.

Interventions

Artist-facilitated arts and health group intervention (HoS) (ten 2-hour sessions over 14 weeks) plus usual care (UC) versus UC.

Outcomes

The outcomes were self-reported measures of well-being, mood, capability, health-related quality of life, self-esteem and self-concept (baseline and 5 months postrandomisation). Key feasibility parameters were gathered, data collection methods were piloted, and participant interviews (n=24) explored the acceptability of the intervention and study processes.

Results

Despite a low recruitment rate (14%; 95% CI 11% to 18%), 88% of the recruitment target was met, with 29 participants randomised to HoS and 27 to UC (57% male; mean (SD) age=70 (12.1) years; time since stroke=9 (6.1) months). Follow-up data were available for 47 of 56 (84%; 95% CI 72% to 91%). Completion rates for a study-specific resource use questionnaire were 79% and 68% (National Health Service and societal perspectives). Five people declined HoS postrandomisation; of the remaining 24 who attended, 83% attended ≥6 sessions. Preliminary effect sizes for candidate primary outcomes were in the direction of benefit for the HoS arm. Participants found study processes acceptable. The intervention cost an estimated £456 per person and was well-received (no intervention-related serious adverse events were reported).

Conclusions

Findings from this first community-based study of an arts and health intervention for people poststroke suggest a definitive RCT is feasible. Recruitment methods will be revised.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN99728983.

Keywords: stroke, identity, wellbeing, feasibility study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first feasibility study of a community-based arts and health group intervention to support well-being following a stroke.

Participants were recruited via both hospital and community clinical teams, enabling recruitment rate estimates for two different recruitment approaches.

The study incorporated mixed methods and a feasibility economic component.

The study only included short-term follow-up.

Findings will inform a definitive randomised controlled trial of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Introduction

Each year over 150 000 people in the UK experience a stroke,1 with one-third left with residual disabilities including paralysis on one side and cognitive and communication impairments.2 Qualitative meta-syntheses have highlighted that following a stroke, or other types of brain injury, people face fundamental emotional and existential challenges. They experience challenges to their sense of self and identity, and their current and future lives are filled with uncertainty.3 4 Emotional health and well-being following stroke have been highlighted as national priorities, featuring in the James Lind Alliance ‘top ten’ research priorities.5

Following a stroke people report a need to ‘get their lives back’. Failure to do so is associated with depression6 7 (with reported accumulative incidence of 39%–52% within 5 years of stroke7), loss of confidence,8 having difficulty in ‘feeling part of things’,9 loss of sense of self10 and becoming socially isolated.11 This creates long-term costs for the stroke survivor and family members,12 13 and for government, health and social services through reduced family employment and increased social and primary care needs.14 Left untreated, depression is associated with poorer functional outcomes15 and higher mortality.16 17

While there have been great improvements in stroke care, the stroke pathway for long-term support is still under-researched and under-developed. A Cochrane review indicated no evidence for pharmacotherapy in the prevention of poststroke depression, and only weak evidence for psychotherapeutic approaches.18 A more recent systematic review,19 that limited inclusion to participants without a diagnosis of depression at baseline, concluded that antidepressants may reduce the likelihood of depression developing poststroke, but that the optimal timing and duration of treatment were not clear. There is also evidence to suggest that pharmacological treatments can have modest benefits in the treatment of depression poststroke.20–23 However, antidepressants have side effects and may have undesirable interactions with other medications and/or comorbidities.20–23

While the evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for poststroke depression is inconclusive,20 two recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (motivational interviewing24 25 and a brief psychosocial behavioural intervention plus antidepressant26) demonstrated reductions in poststroke depression. However, these trials involved people early after stroke and excluded those with severe communication or cognitive problems. The CALM (Communication and Low Mood) trial27 of behavioural therapy demonstrated improved mood in patients with stroke with aphasia, and a feasibility study of behavioural activation is now under way using a broader sample of people with depression 3–60 months poststroke.28 A study of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for poststroke depression demonstrated no benefits over usual care or an attention control; however, the sample size was small.29

Around 20% of people experience clinical levels of anxiety following stroke.30 A recent Cochrane review highlighted the need for further rigorously conducted RCTs to assess pharmacological and psychological treatments for anxiety following stroke.30

A stepped approach to psychological support following stroke has been proposed in the UK31 (step 1: awareness, watching; step 2: low-intensity services, such as guided self-help; step 3: high-intensity services, such as CBT), but this system is still in its infancy.

Harrison et al32 concluded from qualitative research with service users that research is needed to test alternative options to formal psychological support. Ellis-Hill et al33 and Gracey et al34 have independently developed complementary theoretical models based on empirical evidence to understand the processes involved in re-establishing a positive sense of self and confidence in life following a stroke. The current research draws on two specific and related theoretical frameworks; namely, the life thread model33 and self-discrepancy theory.9 34 These highlight that following an acquired brain injury people often lose a sense of coherence of self and a sense of predictability in life. These existential losses can cause considerable anxiety and can lead to depression. Within neuropsychological rehabilitation, it is hypothesised that establishing a safe place where clients feel understood and supported can facilitate self-development.34 35 When carrying out embodied creative activities (such as art), people can reconnect their past, present and future selves, recreating meaningful narratives in their lives and new ways of ‘being in the world’,36 37 leading to improvements in mood and self-confidence.

There is increasing recognition of the importance of creative approaches in health provision; for example, in the UK we have seen the launch of a national Special Interest Group for Arts, Health and Wellbeing (now part of the Culture, Health and Well-being Alliance) supported by the Royal Society for Public Health38 and the All-Party Parliamentary Group enquiry into arts, health and well-being in the UK.39 Practical creative approaches offer new ways to explore experiences, especially those which are difficult to put into words.40 There is a growing body of evidence that art-based practices are of great benefit in supporting psychological and social recovery in health services39 and an emerging international agenda for ‘Arts for Health’ initiatives.41 An ongoing prospective observational study (2009–2016) of patients referred to an 8-week or 10-week ‘arts on referral’ programme in UK general practice (n=1297) found statistically significant improvements in well-being in those who completed their prescribed programme.42 Boyce et al’s43 critical review of the value of arts in healthcare highlighted that, although findings are promising, research to date has been relatively narrow both in scope (a focus on music) and methodological approach. They called for methodologically rigorous research that considers different art forms in a variety of healthcare settings and their cost-effectiveness.

In stroke, initial findings from exploratory studies of the effect of art on mood have been promising.44 45 To our knowledge, there are only two other RCTs of arts and health interventions in stroke, both of which took place in inpatient rehabilitation settings.46 47 Kongkasuwan et al’s study in Thailand involved 118 patients with stroke and compared ‘creative art therapy’ plus standard physiotherapy with physiotherapy only.46 The creative art therapy was delivered by art therapists twice a week over 4 weeks and included music, singing and meditation in addition to the creative art therapy activities. They found improvements favouring the intervention group post-treatment in measures of mood, cognition, physical functioning and quality of life. Morris et al’s47 48 UK randomised controlled feasibility study (n=81) compared an artist-delivered visual arts participation programme (up to eight sessions including individual and group delivery formats) with usual care. They concluded that the intervention was feasible to deliver and appeared to offer promise in the domains of emotional well-being and self-efficacy.

White et al49 highlighted that community participation and stroke-related disability are potentially modifiable risk factors affecting poststroke health-related quality of life and that interventions addressing these factors should be developed and tested. This feasibility study50 is the first to begin to systematically test an arts and health intervention (‘HeART of Stroke’ (HoS)) for people poststroke in a community setting.

Methods

Aims and objectives

The aims of the feasibility study were, first, to assess the acceptability of a 10-session community arts and health group intervention (‘HeART of Stroke’) for people following stroke, and second to evaluate the feasibility of conducting a definitive RCT to test its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness when added to usual care. The following were the specific objectives:

Assess the acceptability of key aspects of study design, randomisation and recruitment processes, and of the HoS group intervention.

Estimate recruitment and short-term retention rates.

Estimate HoS group attendance rates.

Assess the suitability of the outcome measures and feasibility of the assessment strategy.

Refine the selection of the outcome measures, in particular to help inform the selection of the primary outcome for the full-scale RCT.

Explore, qualitatively, individuals’ experiences of participating in the study and gather feedback about the intervention and outcome measures.

Collect data on the SDs of outcome measures to inform a sample size calculation for a larger trial and obtain preliminary estimates of effect size.

Refine the HoS group intervention and its delivery.

Explore differences in processes between the two study centres.

Identify, measure and value resources required to deliver the intervention in the community.

Develop and pilot data collection tools to measure resource use in the follow-up period to inform the design of a future within-trial economic evaluation, and estimate the cost of delivering HoS.

Study design

This was a two-centre, parallel-arm, randomised controlled feasibility study comparing the HoS group intervention plus usual care versus usual care alone (1:1 allocation ratio), with nested economic and qualitative components.

For reasons of efficiency and expediency, the end point of this feasibility study was 1 month postintervention, but a definitive trial would include up to 12 months of follow-up postintervention to capture the longer term health and economic impact of the HoS intervention. One month post-treatment was chosen as the study end point rather than the end of treatment (1) because some of the outcome measures include items with 4-week recall periods (eg, Short-Form 36 (SF-36)) and (2) to reduce the likelihood of capturing transient disappointment about the group coming to an end in those who attended a HoS group.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were involved in the initiation and design of the study, the development of the funding application, the design of the HoS intervention, the selection of relevant outcome measures and the design of study materials. During the research, in addition to RC, a grant holder, who attended all steering group and dissemination meetings, we formed patient and public involvement groups in each centre. There were five patient and public involvement members in Bournemouth (four involved in the study at any one time). Members came from the local voluntary ‘Different Strokes’ group, the Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals (RBCH) NHS Foundation Trust stroke ward patient and public involvement group, and via word of mouth from these members. Four members were several years following their stroke and one person was a caregiver. There were three patient and public involvement members in Cambridgeshire: one was identified through a previous research role and two were identified through community organisations (Stroke Association and National Health Service (NHS) community services). All were several years poststroke.

As planned, patient and public involvement members were involved in three of the five study management group meetings. A newsletter kept patient and public involvement members updated with study progress. Members contributed to the study in many ways, including providing feedback about outcome measures, providing opportunities for the researchers to run through/practise aspects of the study protocol, helping to identify a suitable venue for the intervention, providing ideas on how to enhance recruitment, contributing to plain English summaries, and supporting the exhibition of artwork and other dissemination activities. Examples of dissemination activities undertaken include a workshop at the UK Stroke Forum codelivered by a study participant with two members of the research team (CL-R and CE-H), local newspaper coverage and articles in magazines.

Methods

Details of our methods are published in our protocol paper.50 We aimed to recruit a sample of 64 people (32 per centre in two blocks of 16). This would have provided an estimate of the recruitment rate with a precision of ±6% (assuming a recruitment rate of 30%) and a questionnaire return rate with a precision of ±10% (assuming a questionnaire return rate of 80%). Reporting of this feasibility study follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 extension for randomised pilot and feasibility trials.51

Participants

Participants were adults living in the community up to 2 years poststroke. This time point was chosen as the peak incidence and greatest severity of depression commonly occur between 6 months and 2 years following stroke.52 Participants also had physical or cognitive symptoms from stroke at 5 days poststroke. Severity of stroke and cognitive impairment are risk factors for the development of poststroke depression.53 People who have fully recovered physically and cognitively within this short time point may be less likely to benefit from the intervention. Exclusion criteria included severe receptive aphasia, cognitive levels that would preclude completion of outcome measures even with support, currently receiving a psychiatric or clinical psychology intervention, living in a residential or nursing home, and requiring assistance with toilet needs (because the arts and health practitioners were not trained to support transfers).

Identification, screening and recruitment

Bournemouth Centre, UK (RBCH NHS Foundation Trust)

Potential participants, identified by clinical research network staff at the RBCH NHS Foundation Trust, were either sent or given an invitation letter, ‘Key Facts’ page and reply slip and asked to return a prepaid reply slip if they were interested in participating. The study research assistant contacted those who expressed an interest and answered any queries or questions (via telephone, or face-to-face if the person had a communication disability). If they were still interested in taking part, they were sent or given a set of participant information sheets.

In an attempt to improve recruitment, we revised the invitation and reminder letters partway through the study via an approved substantial amendment to the NHS Research Ethics Committee. Our patient and public involvement partners and clinical colleagues in the stroke research team at RBCH provided feedback to enhance the appeal and readability of the information via a more accessible and engaging style.

Cambridgeshire Centre, UK (Cambridgeshire Community Services NHS Trust)

Clinical staff from the community stroke and neurorehabilitation teams identified potential participants in the community. In addition to the invitation letter described above, a ‘consent to contact’ approach was used whereby consent to be contacted by the Cambridgeshire centre research assistant was sought. A member of the clinical team obtained this consent during a face-to-face consultation or verbally over the phone. If the individual remained interested, the research assistant gave or sent them a set of participant information sheets.

Informed consent process

For individuals interested in taking part, the local research assistant arranged to visit the person at home within 1 month prior to the start of the HoS group. This provided an opportunity to answer any remaining questions the individual had about the study. If the person still fulfilled the eligibility criteria (a screening checklist was used) and still wished to take part, they were asked to complete and sign a consent form and complete the baseline assessment.

Randomisation

The web-based randomisation system was created by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit at Plymouth University in conjunction with the study statistician. Participants were allocated to the HoS intervention plus usual care or usual care in a 1:1 ratio using minimisation to balance the numbers allocated to each arm with stratification by recruitment centre and stroke severity (Rivermead Motor Assessment-gross function subscale score ≤6 (‘mild’) vs ≥7 (‘moderate/severe’)).54 The study research assistants in each centre logged onto the system using a unique username and password. They were able to randomise participants individually or in batches. Randomisation of individuals was used to ‘top up’ the two trial arms if any further participants were recruited before the HoS intervention groups started.

Blinding

The nature of the intervention meant that it was not possible to blind participants and artist facilitators to group allocation. At follow-up, when support was required to complete outcome measures, this was provided by assessors blind to group allocation.

HoS group intervention

The HoS intervention is described in detail in the published protocol.50 In summary, it comprised ten 2-hour arts and health practitioner-led group sessions held in community venues over 14 weeks. Sessions were held in the mornings (10:30–12:30) with a refreshment break. Sessions 1–3 included introductions and initial exploration. During sessions 4–7 participants were encouraged to develop their own creative practice within the sessions and at home. In sessions 8–10 links with local arts and health practitioners were made and potential plans for an exhibition of the participants’ work discussed.

Key aspects of the group were the opportunity to be creative and the safe group atmosphere. At each group, the arts and health practitioners encouraged members to (1) explore the materials provided and arts techniques shared; (2) explore their senses and support others’ explorations; (3) be non-judgemental of self/others; (4) follow and respond to their own interests; and (5) develop a sense of play/improvisation. The arts and health practitioners prepared resources (including paints, drawing materials, clay, textiles and mixed-media) in response to the group members’ individual and collective creative interests and skills. The group was offered ‘stimulus’ pieces such as books, poems, images, music and film, and members were encouraged to share their own pieces of interest with the group.

Examples of artwork produced can be seen in figure 1 and figure 2.

Figure 1.

Drawing by FB.

Figure 2.

Painting by MDBD.

Following each session, the arts and health practitioner briefly documented observations and reflected further to inform the selection of materials and activity for the next session. Practitioners also provided participants with sketchbooks and/or paper and other arts materials to support their emerging interests between sessions.

The rationale of HoS is to provide a safe space through the medium of arts in which group members have the opportunity to reconnect with their internal selves through their senses and embodied knowing and connect with, and support, others. This was a face-to-face group intervention, with self-directed individual art activity opportunities between meetings. Standardisation was linked with the context and setting rather than specified activities carried out by the practitioners and participants as this was expected to vary due to the creative nature of the activity. For example, standardisation included the groups taking place in a non-medical setting, so that the arts and health practitioners could create and hold a safe space in which participants felt able to express themselves creatively. The focus was the person not their stroke. The artists responded to and followed the interests of each participant, rather than solely ‘teaching’ arts skills.

Facilitators and venues

The groups were facilitated by arts and health practitioners, with at least 5 years’ arts and health practice experience, who were able to support groups, create and hold a safe space, and who were willing and able to support arts practice where participants took the lead in their own discovery and exploration. Currently in the UK, arts and health practitioners are not required to undertake specific training but characteristically develop their practice within NHS initiatives working alongside experienced artist mentors or with respected ‘Arts on Prescription’ organisations. One arts and health practitioner led both groups in Bournemouth (CL-R) and two led one group each in Cambridgeshire. They had access to expertise in stroke (CE-H) and clinical psychology (FG). For the purposes of the project, a researcher was also present on site, if needed. The researcher supported study administration aspects (such as travel expenses for participants) and participant completion of a scale (Doosje et al’s Social Identification self-report scale) assessing group fit/sense of belonging.55

In Bournemouth the HoS groups (iterations 1 and 2) were held in a church hall, and in Cambridgeshire they were held either in a room in a community hospital site on the edge of Cambridge city used by Headway Cambridgeshire (a local brain injury charity) (iteration 3) or a community centre in a very rural north Cambridgeshire town (iteration 4). All venues had disabled access/toilet facilities, access to water and a sink, and tea/coffee-making facilities and could accommodate up to eight participants (potentially with wheelchairs) around a table. There were storage facilities (although limited) in Cambridgeshire but none in the Bournemouth venue. Transport was provided for those unable to make their own way to the venue.

Usual care

In Bournemouth, support is provided by the Early Supported Discharge multidisciplinary team for 2–6 weeks after leaving hospital and then medical care via the general practitioner (GP), with a referral to the stroke coordinator. People with complex medical conditions are seen by stroke consultants as hospital outpatients. Ongoing rehabilitation needs are met by rehabilitation teams and day hospital service provision in some areas. In Cambridgeshire, medical care is delivered via the GP and people with complex medical conditions are seen by stroke consultants as hospital outpatients. At the time of the study all could access support from the Stroke Association ‘Information, Advice and Support Coordinator’ and may have received additional therapy or support via one of three locality-based neurorehabilitation teams. Participants in both arms of the trial received usual care, and usual care was not affected by involvement in the trial.

Descriptors and proposed outcome measures

Demographic/descriptor variables and stroke-related information

At baseline the local research assistant collected information during a home visit about age, sex, marital status, educational qualifications, ethnicity, household composition, employment situation, comorbidities, medication, type of stroke, stroke side, time since stroke, mobility (Rivermead Motor Assessment-gross function subscale),54 upper limb impairment (Motricity Index),56 communication ability (Boston Severity Rating Scale)57 and cognitive ability (Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised; ACE-R).58

Outcome measures

The outcome measures (see below) were self-reported and presented in a booklet in a large font (pt 14). At baseline, outcome measures were administered face-to-face by a research assistant in participants’ homes. At approximately 5 months postrandomisation (1 month post-HoS intervention), outcome measures were administered by post, or if needed, with face-to-face or telephone support from a blinded assessor (one in each centre). At the end of the questionnaire booklet, there was a question that asked whether participants had received any support from others to complete it, with the following response options possible: none, researcher on phone, researcher at house, family member/friend. Participants were asked not to disclose their allocation arm to the blinded assessors. In each centre the blinded assessors were asked to guess participants’ treatment allocation.

In line with the feasibility objectives of this study, three outcome measures were included for consideration as potential candidates for the primary outcome in a subsequent full trial:

Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS).59

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).60

ICEpop CAPability measure for adults (ICECAP-A).61

In addition, the following outcome measures were included as potential secondary outcomes:

Serious adverse events and adverse events

Serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events (AEs) were closely monitored, documented and reported as described in the study protocol.50

Process measures

Doosje et al’s Social Identification self-report scale55 was used to measure ‘sense of belonging’ by participants in the HoS group at the end of the first, fifth and final sessions.

Identifying, measuring and valuing resource use

Resources required to deliver the HoS intervention were recorded for each session on forms completed by the artist facilitators. These included artists’ preparation time, travel time to and from the venue, time spent delivering the intervention, equipment and materials used, number of participants attending the sessions, and venue hire costs. Resources were valued using local estimates provided by the experienced artists delivering HoS. Artist facilitators’ time was valued at the fixed fee of £120 per session (to cover travel, preparation and delivery costs), with an additional £25 fee for materials and £8 for refreshments. Venue hire costs in Bournemouth (iterations 1 and 2) were £40 per session, and in Cambridgeshire £100 per session (iteration 3) and £25 per session (iteration 4). We envisage the roll-out of the HoS intervention would follow a similar model whereby the healthcare provider would pay the artist facilitators a fixed delivery fee. Participant travel costs to attend sessions were recorded and are reported.

Resources required to deliver usual care in both arms were collected via a bespoke telephone-administered resource use questionnaire that asked about resources used in the period following randomisation. Participants were posted the questionnaire in advance of the telephone interview and were offered face-to-face support to complete it, if required. The questionnaire included hospital visits and admissions, use of community and social services, time off work and social activities, informal care, other sources of support, expenses incurred and medications. As service users advised us that it would be difficult to distinguish between stroke-related resource use and resource use related to comorbidities, the questionnaire asked respondents to report resources related to all their healthcare needs. We assume that, in a definitive RCT, any differences between arms would result from the HoS intervention effect. To improve completion rates,65 participants were provided with a resource use log to record healthcare visits prospectively, if they wished. Resources were valued using Curtis and Burns’ Unit Costs of Health and Social Care66 and the 2015 Department of Health NHS reference costs.67 Private expenses were self-reported. Hours of informal care and time off work and social activities were valued using the Office for National Statistics (2015) average weekly earnings.68

Qualitative descriptive interviews

Face-to-face interviews with 12 people (8 intervention; 4 usual care) were undertaken in people’s homes across both centres by CE-H on two occasions: (1) postrandomisation but before the HoS intervention was delivered; and (2) at study end after all outcome measures had been completed. Purposive sampling was used to capture variations that might influence perceptions, including age, sex, communication disability and severity of stroke. The preintervention topics included why the person decided to take part in the overall study, their views on the recruitment and initial assessment process, and (intervention group only) expectations in terms of the HoS group intervention. The postintervention topics included views on the study and outcome assessment processes and the acceptability of completing outcomes at 1-year follow-up in the context of a hypothetical future trial. Intervention participants were also asked about their experiences of the group, the venues and their ability/willingness to pay their own transport costs to attend HoS.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS V.23.0 and STATA V.14. The person undertaking the analysis was blind to allocation and group assignment was coded using 0 and 1. As this was a feasibility study, analyses were primarily descriptive and focused on baseline participant characteristics and the estimation of key feasibility parameters.69 Estimates of recruitment, retention and questionnaire completion rates are presented with 95% CIs. Intervention attendance rates are described.

Preliminary estimates of effect size with 95% CIs are presented for the three candidate primary outcomes to inform the plausibility of the effect sizes used in future sample size calculations. Participants were analysed in the group they were randomised to, and we attempted to collect outcome measure data from everyone randomised. Missing data were assumed to be missing completely at random and no imputation methods were used. Analysis of covariance was used to estimate the effect size for each outcome variable at follow-up, adjusting for centre and the respective baseline values. Although stroke severity was a stratification variable in the randomisation, we have not adjusted for it in the analysis because of the very small number with severe stroke. In the future trial we would also take into account clustering effects resulting from the group-based nature of the HoS intervention.70 We have not taken into account clustering in the analysis presented here because (1) this is a feasibility study where the aim is not to obtain precise estimates of effect size, and (2) there were just 56 participants (29 receiving the HoS intervention) and only a small number of clusters (n=4), making it difficult to adjust for clustering. A consequence is that widths of the 95% CIs are likely to be underestimated. Standardised effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were obtained by dividing effect sizes by pooled baseline SD.

Economic analysis

We report completion rates for the resource use categories. A preliminary estimate of the cost of delivering the HoS intervention was derived using macro-level costings. We also report artist facilitator time to deliver the intervention at the micro-level and participant travel expenses incurred attending the HoS sessions.

We further report resource use units and costs per category per trial arm, for an indication of cost drivers for the intervention from the health and social care perspective. We derived capability index scores for the ICECAP-A71 and applied UK preference-based tariffs to the Short Form-6 Dimensions (SF6-D) to derive quality adjusted life years (QALYs).72

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative analysis consisted of two aspects: (1) a content analysis73 of participants’ views of the research processes, which is presented in this paper; and (2) a thematic analysis74 of participants’ expectations and experiences of the HoS group, which will be reported separately.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. For the content analysis CE-H read each transcript and for each one noted responses to the specific questions relating to the research processes; such as recruitment, screening and the administration of outcome measures, as well as the acceptability of the venue, the intervention and potential willingness to pay for the intervention (latter three, intervention group only). These specific responses were then collated across participants by CE-H.

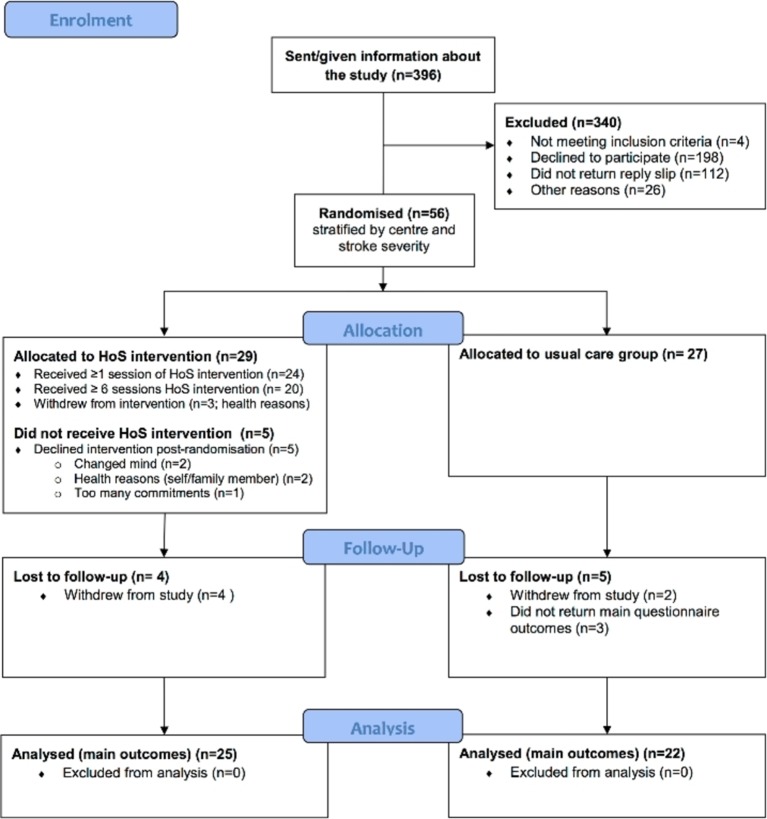

Study procedures, recruitment and retention rates

Fifty-six people were randomised (88% of our original target of 64) (see figure 3). Nearly two-thirds of the sample were male, the mean age of the sample was 70 (SD 12.1) years, and the mean time since stroke was 9 (SD 6.1) months. Approximately 80% of participants had had an ischaemic stroke. Seventy per cent of the sample was retired (see table 1). One participant who had had their stroke outside the 2-year poststroke inclusion time window (32 months poststroke) was erroneously recruited into the study. We included this participant’s data in the analysis.

Figure 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. HoS, HeART of Stroke.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and demographic descriptives for the sample

| Descriptors | Usual care (n=27) |

HeART of Stroke (n=29) |

Entire cohort (n=56) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| female; male | 7 (26); 20 (74) | 17 (59); 12 (41) | 24 (43); 32 (57) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) range | 67.4 (12.83) 39–88 | 72.0 (11.22) 27–87 | 69.8 (12.13) 27–88 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White English | 25 (93) | 23 (79) | 48 (86) |

| White other British | 1 (4) | 5 (17) | 6 (11) |

| Mixed-white and Asian | 1 (4) | – | 1 (2) |

| Black or black British-African | – | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Time since stroke (months), median (IQR) range* | 7 (5) 2–19 | 7 (7) 1–32 | 7 (5) 1–32 |

| Stroke type, n (%) | |||

| Ischaemic/thrombotic | 6 (22) | 5 (17) | 11 (20) |

| Ischaemic/embolic | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Haemorrhagic/intracerebral | 2 (7) | 2 (7) | 4 (7) |

| Haemorrhagic/subarachnoid | – | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Ischaemic/type unknown | 13 (48) | 16 (55) | 29 (52) |

| Haemorrhagic/type unknown | 4 (15) | 3 (10) | 7 (13) |

| Type unknown | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Stroke severity (Rivermead Motor Assessment - gross function subscale), n (%) | |||

| Total score ≤6 | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | 3 (5) |

| Total score ≥7 | 26 (96) | 27 (93) | 53 (95) |

| Stroke side, n (%) | |||

| Left | 11 (42) | 15 (52) | 26 (47) |

| Right | 13 (50) | 11 (38) | 24 (44) |

| Both sides | 1 (4) | 3 (10) | 4 (7) |

| Not applicable | 1 (4) | – | 1 (2) |

| Missing | 1 | – | 1 |

| Centre, n (%) | |||

| Bournemouth | 16 (59) | 17 (59) | 33 (59) |

| Cambridgeshire | 11 (41) | 12 (41) | 23 (41) |

| Level of education (highest qualification), n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 3 (12) | 8 (30) | 11 (21) |

| One or more General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) or equivalent | 4 (16) | 4 (15) | 8 (15) |

| One or more General Certificate of Education (GCE) A- (Advanced) level or equivalent | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 6 (12) |

| First degree or higher | 1 (4) | 5 (19) | 6 (12) |

| Other | 12 (48) | 9 (33) | 21 (40) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Prestroke employment status, n (%) | |||

| Retired | 14 (52) | 25 (86) | 39 (70) |

| Full-time employment | 3 (11) | 1 (3) | 4 (7) |

| Part-time employment | 3 (11) | 1 (3) | 4 (7) |

| Self-employed | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | 3 (5) |

| Other (unemployed; home maker) | 5 (19) | 1 (3) | 6 (11) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 4 (15) | 3 (10) | 7 (13) |

| Married/cohabiting | 17 (63) | 13 (45) | 30 (54) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (11) | 3 (10) | 6 (11) |

| Widowed | 3 (11) | 10 (34) | 13 (23) |

| Household composition, n (%) | |||

| Living alone | 9 (33) | 13 (45) | 22 (39) |

| Living with others | 18 (67) | 15 (52) | 33 (59) |

| Sheltered housing | – | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Taking medication for mood, n (%) | |||

| No | 21 (78) | 24 (86) | 45 (82) |

| Yes | 6 (22) | 4 (14) | 10 (18) |

| Missing | – | 1 | 1 |

| Communication difficulties†, n (%) | |||

| No | 18 (67) | 12 (41) | 30 (54) |

| Yes | 9 (33) | 17 (59) | 26 (46) |

| Motricity Index total score‡, median (IQR), n | 100 (27) 12–100, 27 | 84 (29) 1–100, 29 | 84.5 (27) 1-100, 56 |

*Although the inclusion criterion for the study was ≤24 months poststroke, we erroneously recruited one participant at 32 months poststroke and this participant’s data are included in the analysis.

†Boston Severity Rating Scale.

‡For one case there was a missing value for one item and this was replaced by the mean.

Participants were enrolled into the study between August 2014 and April 2015 and the final follow-up occurred in December 2015. The recruitment rate across both centres was 14% (95% CI 11% to 17%). In Bournemouth, an acute hospital setting, the recruitment rate was 11% (95% CI 8% to 14%), and in Cambridgeshire, a community setting, it was 28% (95% CI 19% to 38%).

In total, information about the study was given or sent to 396 people (313 in Bournemouth and 83 in Cambridgeshire). Of these, 198 people declined participation, 112 did not return the reply slip, 4 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 26 were excluded for ‘other reasons’ (see figure 3).

Six participants (11%) withdrew from both the study and follow-up data collection and three participants (5%) did not return the main outcome measures at follow-up. For two of the three proposed potential primary outcomes (HADS and ICECAP-A), 47 of 56 (84% (95% CI 73% to 92%)) of the randomised participants had complete baseline and follow-up data, and 46 of 56 (82% (95% CI 70% to 91%)) had complete baseline and follow-up data for the WEMWBS.

Reasons for non-participation

Of 198 people declining participation, 89 gave reasons, the most common ones related to not being interested/feeling the intervention “wasn’t for them” (n=27) and health reasons (n=14).

Delivery, attendance rates and group size

Five participants allocated to the HoS arm declined the intervention postrandomisation (see CONSORT diagram for reasons). Of the 29 participants randomised to the HoS intervention, 20 (69% (95% CI 51% to 84%)) attended 6 or more of the 10 sessions.

Two HoS groups were delivered in Bournemouth (iterations 1 and 2) and two in Cambridgeshire (iterations 3 and 4). The timing of the HoS sessions deviated slightly from that specified in the original protocol in three of the four iterations due to venue availability and the timing of public holidays. The planned group size was six to eight participants, and this target was mostly met in iterations 1–3 with 73% (22/30) of the delivered sessions including six or more people. In iteration 4, due to time pressures (the grant coming to an end), only 11 people were randomised, with 6 allocated to the intervention. There were two dropouts before the group commenced and one person withdrew after the first session, meaning that 90% of sessions included three people or fewer. A summary of attendance at the HoS groups broken down by centre and session is presented in online supplementary table S1. Seventy-two per cent of the participants randomised to the HoS arm attended the final session (session 10) of the HoS group intervention.

bmjopen-2017-021098supp001.pdf (51.3KB, pdf)

Self-reported ratings on the domains of Doosje et al’s Social Identification self-report scale (measuring ‘sense of belonging’)55 increased across sessions and remained high in the final session (see online supplementary table S2).

Support requirements for HoS group members

At the Cambridgeshire centre, one of the artist facilitators discussed a HoS group member’s cognitive needs with FG (clinical psychology). Subsequently, several adaptations were identified and implemented, such as providing a small sketchpad when needing to wait for additional support and providing instructions one step at a time.

Suitability of the outcome measures and feasibility of the assessment strategy

The ACE-R was originally designed as a screening tool for dementia and provides a single overall total score, with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning. It relies heavily on language abilities, meaning that people with aphasia can perform poorly on domains such as memory because of language impairments.75 It did not prove suitable for our sample, of whom nearly half (46%) had some degree of language difficulty. For this reason we have not presented the baseline descriptive data for the ACE-R as we do not feel they provide an accurate summary of the sample’s cognitive abilities given that some of the domains rely on verbal fluency and expression.

Overall, participants found the self-reported outcome measures acceptable and were able to complete them, sometimes requiring support. However, several participants noted to the blinded assessors that they had found the HISDS-III difficult to complete (in terms of understanding the meaning of some of the bipolar adjective pairs and also in understanding the response format of the scale). These difficulties were reflected in some of the polarised response patterns obtained and corroborated by the blinded assessors’ experiences. For these reasons we have not presented these data.

Missing questionnaire data were followed up via telephone by a research assistant (baseline) or blinded assessor (follow-up) at each centre. Levels of missing data were very low—overall, 99.8% of the questionnaire items comprising the candidate primary outcomes were completed (1809/1815 items at baseline and 1550/1551 items at follow-up) by those who provided outcomes (at baseline n=55 and follow-up n=47).

Support requirements to complete outcomes

At follow-up, the self-report questionnaire booklets were administered via post by default, but face-to-face support was provided if required/requested. Fifty-eight per cent of those with follow-up data (26/45, data for 2 cases missing) reported that they completed the questionnaire booklet with no support, 8 (18%) received support from the blinded assessor in the home, 10 (22%) received support from family and friends, and 1 (2%) received telephone support from the blinded assessor.

Possible primary outcomes

In table 2 we present descriptives for the possible primary outcomes (WEMWBS, HADS-anxiety subscale (HADS-A), HADS-depression subscale (HADS-D), ICECAP-A), and descriptives for all other outcomes gathered are presented in online supplementary table S3.

Table 2.

Descriptives and preliminary estimates of effect size for potential primary outcomes

| Outcome measure | Baseline, n=56 | Mean difference (95% CI) |

Post, n=47 | Standardised effect size (Cohen’s d)* |

| Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (potential range 14–70, higher scores greater well-being) | ||||

| UC mean (SD) n | 49.1 (10.29) 26 | 48.0 (8.20) 22 | ||

| HoS mean (SD) n | 48.4 (9.18) 29 | 48.4 (10.28) 25 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (unadjusted) | 2.25 (−2.83 to 7.32) | 0.23 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (adjusted for centre and baseline score) | 1.14 (−3.42 to 5.70) | 0.12 | ||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-anxiety subscale (potential range 0–21 each subscale, higher scores greater anxiety) | ||||

| UC mean (SD) n | 7.0 (3.83) 27 | 7.0 (4.13) 22 | ||

| HoS mean (SD) n | 7.3 (4.21) 29 | 6.3 (3.74) 25 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (unadjusted) | −0.47 (−2.48 to 1.54) | −0.12 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (adjusted for centre and baseline score) | −0.55 (−2.39 to 1.28) | −0.14 | ||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-depression subscale (potential range 0–21 each subscale, higher scores greater depression) | ||||

| UC mean (SD) n | 5.0 (2.74) 27 | 6.1 (3.33) 22 | ||

| HoS mean (SD) n | 6.1 (3.75) 29 | 6.0 (4.18) 25 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (unadjusted) | −1.82 (−3.42 to −0.22) | −0.56 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (adjusted for centre and baseline score) | −1.46 (−3.12 to 0.21) | −0.45 | ||

| ICECAP-A tariff (potential range 0–1, higher scores greater capability) | ||||

| UC mean (SD) n | 0.81 (0.14) 26 | 0.78 (0.15) 22 | ||

| HoS mean (SD) n | 0.77 (0.16) 29 | 0.76 (0.22) 25 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (unadjusted) | 0.05 (−0.03 to 0.13) | 0.33 | ||

| Mean difference (95% CI) in change from baseline (adjusted for centre and baseline score) | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.12) | 0.26 | ||

Where high scores indicate better outcomes, positive effect sizes suggest benefit for the HoS arm.

Where low scores indicate better outcomes, negative effect sizes suggest benefit for the HoS arm.

*Effect sizes based on complete cases.

HoS, HeART of Stroke; ICECAP-A, ICEpop CAPability measure for adults; UC, usual care.

Completion of resource use questionnaire

The resource use questionnaire was completed by 50 of 56 participants (89%): 25 of 29 patients in the HoS arm and 25 of 27 patients in the usual care arm. Of these, 33 (66%) were administered over the telephone, 16 (32%) face-to-face at home and 1 (2%) via the post. Although not included in the original study protocol, duration data were logged in the Bournemouth centre, with the 19 telephone interviews lasting 23 min (SD=10) on average and the 8 face-to-face administrations in the home lasting 38 min (SD=13) on average.

Completion rates of resource use categories were high and similar between the two study arms (table 3). The least completed category was community-based services, such as primary care visits (see table 3), with 90% complete data for this category (both trial arms combined). Seventy-nine per cent complete data (out of the full sample) are available for an economic analysis from the health and social care perspective.

Table 3.

Completeness of resource use data

| Complete data (n) | % of questionnaires filled in (n=25) | % of sample (n=29) |

Complete data (n) | % of questionnaires filled in (n=25) | % of sample (n=27) |

|

| Intervention | Usual care | |||||

| Health and social care | ||||||

| Outpatient visits | 25 | 100 | 86 | 25 | 100 | 93 |

| Inpatient visits | 25 | 100 | 86 | 25 | 100 | 93 |

| Community-based services | 21 | 84 | 72 | 24 | 96 | 89 |

| Personal social services | 25 | 100 | 86 | 24 | 96 | 89 |

| Total health and social care | 21 | 84 | 72 | 23 | 92 | 85 |

| Further resource use collected | ||||||

| Time off work | 25 | 100 | 86 | 23 | 92 | 85 |

| Time off normal activities | 25 | 100 | 86 | 25 | 100 | 93 |

| Hours of help per week | 21 | 84 | 72 | 24 | 96 | 89 |

| Private therapies used | 25 | 100 | 86 | 25 | 100 | 93 |

| Charity/support group contacts | 25 | 100 | 86 | 25 | 100 | 93 |

Assessor allocation guesses

At the Cambridgeshire centre, due to a delay in receiving approval for patient access for the blinded assessor, the unblinded research assistant administered follow-up outcomes to six participants. Overall 50 of 56 participants (Cambridgeshire=23; Bournemouth=27) completed questionnaire outcome measures and/or telephone resource use questionnaires at follow-up. In Cambridgeshire, the blinded assessor correctly guessed allocation on 9 of 17 (53%) occasions (p=1.00 using the exact binomial test to compare with expected percentage of 50%). (NB: The six outcome assessment occasions in Cambridgeshire that were not undertaken by a blinded assessor are excluded.) In Bournemouth, the blinded assessor correctly guessed allocation on 24 of 27 (89%) occasions (p<0.001). Thus overall the blinded assessors correctly guessed allocation on 33 of 44 (75% (95% CI 61% to 85%)) occasions (p=0.001).

SAEs and AEs

Five SAEs were reported during the study period. None was deemed related to the intervention. These included admissions to hospital for bunion removal, facial weakness and vomiting, atrial fibrillation, pneumonia, and a transient ischaemic attack.

Five AEs were noted. None was deemed related to the intervention. Four people attended the emergency department but were not admitted (water retention, fall at home, fall in the road, anxiety). One person sustained a minor injury to their arm at home.

Cost of delivering the HoS intervention

The cost of delivering the HoS intervention was £1960 in Bournemouth and £2530 in Cambridgeshire, reflecting higher venue hire costs in Cambridgeshire (see table 4). On average, six participants attended the two HoS iterations held in Bournemouth and four attended the two HoS iterations held in Cambridgeshire. The HoS intervention would cost the healthcare payer, on average, £327 per participant in Bournemouth and £657 in Cambridgeshire. The cost could be as low as £245 per participant at a full capacity of 8 people.

Table 4.

HeART of Stroke (HoS) delivery costs

| Cost of delivering HoS | Bournemouth | Cambridgeshire |

| Costs for 10 sessions | ||

| Artist fee | £1200 | £1200 |

| Venue cost | £430 | £1000 |

| Materials cost | £330 | £330 |

| Total | £1960 | £2530 |

| Mean number of participants per session | 6.0 | 3.9 |

| Cost of HoS per participant (based on mean attendance) | £327 | £657 |

| Cost of HoS per participant at capacity (eight attendees) | £245 | £316 |

| Reporting micro-level resource use to deliver HoS | ||

| Artist time (in mean hours) | ||

| Session duration | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Preparation time | 20.0 | 10.6 |

| Travel time | 15.0 | 15.6 |

| Total intervention time | 55.0 | 46.7 |

| Participant travel costs | £1021 | £658 |

Health-related quality of life gain, resource use and costs

Table 5 reports the QALY gains from baseline and resource use and costs for the HoS and usual care arms. Potential cost drivers for the intervention are inpatient and outpatient appointments and contacts with a social worker.

Table 5.

Outcomes resource use and cost of delivering care in both arms

| HoS intervention | Usual care | |||||||||||

| n | Users (n) | Mean use | SD | Mean cost | SD | n | Users (n) | Mean use | SD | Mean cost | SD | |

| Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| QALYs gained (Short Form - 6 Dimensions (SF-6D) | 22 | – | 0.18 | 0.03 | – | – | 21 | – | 0.17 | 0.02 | – | – |

| Inpatient and A&E | ||||||||||||

| Inpatient admissions | 25 | 3 | 0.9 | 3.0 | £49 | £136 | 25 | 3 | 0.7 | 2.8 | £96 | £308 |

| Accident & Emergency or hospital admissions | 25 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | £22 | £53 | 25 | 6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | £34 | £61 |

| Outpatient appointments | ||||||||||||

| Stroke rehabilitation | 25 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | £10 | £50 | 25 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | £20 | £69 |

| Physiotherapy | 25 | 3 | 0.3 | 1.2 | £6 | £23 | 25 | 4 | 1.0 | 2.9 | £20 | £56 |

| Occupational therapy | 25 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | £1 | £4 | 25 | 3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | £3 | £9 |

| Speech and language therapy | 25 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | £4 | £16 | 25 | 2 | 0.4 | 1.6 | £7 | £30 |

| Psychologist | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | £0 | £0 | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | £0 | £0 |

| Dietitian | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | £0 | £0 | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | £0 | £0 |

| Other outpatient appointments | 25 | 14 | 1.2 | 1.5 | £140 | £210 | 25 | 13 | 2.0 | 3.2 | £196 | £393 |

| Community-based services | ||||||||||||

| GP contacts | 24 | 17 | 1.9 | 1.5 | £92 | £79 | 25 | 18 | 1.6 | 2.0 | £72 | £83 |

| GP nurse contacts | 25 | 11 | 1.6 | 3.0 | £22 | £44 | 25 | 16 | 2.0 | 3.1 | £26 | £40 |

| Physiotherapy contacts | 25 | 3 | 0.3 | 1.2 | £6 | £23 | 25 | 2 | 0.9 | 3.7 | £19 | £78 |

| Speech and Language Therapy contacts | 24 | 3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | £25 | £82 | 25 | 3 | 1.1 | 3.5 | £94 | £308 |

| Occupational therapy at home | 25 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | £5 | £25 | 25 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | £7 | £27 |

| Repeat prescriptions from GP | 23 | 16 | 4.0 | 5.6 | £5 | £7 | 24 | 18 | 4.0 | 4.3 | £5 | £5 |

| Other community-based appointments | 21 | 2 | 0.4 | 1.4 | £25 | £77 | 24 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.6 | £28 | £143 |

| Personal social services | ||||||||||||

| Home care worker contacts | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | £0 | £0 | 24 | 2 | 0.9 | 3.4 | £11 | £41 |

| Social worker contacts (hours) | 25 | 2 | 0.4 | 1.6 | £28 | £127 | 25 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | £24 | £72 |

| Food at home services (meals) | 25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | £0 | £0 | 25 | 1 | 0.6 | 3.2 | £4 | £21 |

GP, general practitioner; HoS, HeART of Stroke; QALY, quality adjusted life year; n, number of participants reporting; Users (n), number of participants who reported and used the resource.

Acceptability of study processes and intervention logistics

All 12 people who were purposively sampled for interview (8 intervention, 4 usual care) were interviewed on two occasions (male=7, female=5; mean age=70 years (range 51–83 years); mean time since stroke=7 months (range 4–12 months); mean interview duration 40 min (range 10–65 min)). Most had had a mild and one a moderately disabling stroke. Nine had an affected arm and five had speech difficulties. Participants were positive about the study processes and reported finding the screening and baseline measures easy to complete with the support provided (“not too bad”, or “no trouble, it was quite straightforward”). One person commented negatively on the cognitive assessment as her husband who lived with dementia had had to complete it in the past. Participants found the outcome measures and resource use questionnaire acceptable (“it was all right, yeah”; “no problems, no problems at all”). Some people valued receiving the resource use log to complete as they went along saying “it was helpful to do it beforehand”, or using the paper versions of questionnaires that were sent in advance to supplement telephone interviews saying it was not a problem due to “the fact that I had it in front of me as well”. One person noted they would have liked more opportunities for open answers on the questionnaires so they could provide some explanations about their responses. All interviewees would have been happy to complete outcome measures at 4 and 12 months follow-up, if asked.

Timing of sessions (held in the morning) and session duration (2 hours) were acceptable. While the venues were found to be satisfactory, a few people mentioned that they would have liked access to a café where they could meet following the HoS sessions. Participants in Bournemouth were willing to pay up to £10 per session for transport if required. As all but one interviewee in Cambridgeshire drove to sessions (it was a much more rural setting than Bournemouth) and were happy to do so, transport costs were not discussed during the interviews. The one interviewee who used transport in Cambridgeshire only attended one session due to health issues (unrelated to stroke). Findings related to expectations and experiences of taking part in the groups will be reported elsewhere.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first study to formally test the feasibility of an arts and health intervention for people poststroke in the community. While there are two other RCTs of arts and health interventions in stroke,46–48 both of these involved inpatients in a rehabilitation setting rather than people living in the community. One involved a creative art intervention that, unlike HoS, was highly prescribed, making direct comparisons difficult.

Attendance at the HoS intervention groups was high. The majority of people who took part in the HoS groups highly valued them, with many reporting increased confidence both within and outside the groups. The numbers who declined the intervention were similar to those reported in the Morris et al study.47 48 Study retention was good (with follow-up data available for 84% of participants) and high data completion rates (>80% for the candidate primary outcome measures).

The structured breaks between the HoS sessions were potentially instrumental in encouraging participants to continue artwork outside the group. The links created with local arts and health practitioners led to some participants continuing more independent creative practice after the research ended. Important practical considerations include ensuring that venues are on public or community transport routes, have free and disabled car parking facilities, heating/air conditioning and drink-making facilities. In the full multicentre trial, to maximise recruitment and be as inclusive as possible, transport will be provided, if required.

The included outcome measures were mostly acceptable (but see the Limitations: implications for a future trial section), with some participants requiring support to complete them. The possible primary outcome measures for the future trial (WEMWBS, HADS-D, HADS-A, ICECAP-A) all demonstrated change in the direction of benefit for the HoS arm. In Morris et al’s randomised controlled feasibility study of a visual arts participation intervention for inpatients with stroke, a quality of life scale was initially suggested as the likely primary outcome for a future trial. However, their findings suggested that a measure of emotional well-being (the Positive and Negative Affect Scale) would be a more relevant primary outcome measure. Similarly, in the current study a measure of emotional well-being (HADS-D) is being considered as the primary outcome for a subsequent definitive trial and, with medium standardised effect sizes, it is likely that such a trial would be feasibly sized.

We have used novel dissemination methods such as making a short film involving people who attended the HoS groups in Bournemouth, and holding an art exhibition in both Bournemouth and Cambridgeshire to showcase the creations of the HoS group members.

Limitations: implications for a future trial

We did not quite reach our original recruitment target and the overall recruitment rate was low (although not unlike that reported in another community-based study76). In the current study, the recruitment rate in the community setting (28%) was higher than that via hospitals (11%). This might be because in Cambridgeshire recruitment was undertaken by clinicians working in the community who often had a long-standing relationship with their clients. In contrast, at Bournemouth and Christchurch hospitals, while some potential participants were known to and approached directly by the research nurses, others were identified from clinical databases and sent study information in the post.

The most common reason for people declining participation in the current study was because they felt the intervention “wasn’t for them”. Similarly Morris et al48 reported that the majority of people who declined participation in their feasibility study of a visual arts participation programme did so because they were ambivalent about art participation. Modifying the description of the HoS intervention, such as referring to it as ‘an opportunity to reconnect with and gain confidence in everyday life’, rather than calling it an arts intervention could be one way to enhance recruitment. Morris et al suggested that provision of taster sessions may be another means of improving study enrolment,48 although we note a risk of jeopardising equipoise or increasing the likelihood of resentful demoralisation. Additionally, we could extend the eligibility criteria by providing additional support so that those who require support with toileting needs could attend, although this would have cost implications. Finally, we could also expand the recruitment strategy to include primary care. We will continue to consult with service users and stakeholders to seek their advice on ways of increasing recruitment rates and how best to convey the essence of the intervention to people.

The resource use data obtained in this feasibility study provide insights into the main potential cost drivers for the intervention, meaning that we can refine and shorten the resource use questionnaire for the definitive trial. While administering the resource use questionnaire by telephone resulted in high levels of data completeness, maintaining assessor blinding at follow-up proved challenging, particularly in the Bournemouth centre. To try to increase the success of assessor blinding, we will add instructions on the printed versions of the outcome measures that emphasise the importance of not disclosing allocation group and will reword the question in the resource use questionnaire that asks about contacts with charities, social or activity groups. We will also seek patient and public involvement advice about how we can best convey the message not to disclose allocation at the start of the telephone resource use interview, and based on this will create a standard script. We will provide training for the blinded assessors.

Some participants reported finding the HISDS-III difficult to complete. For these reasons we would not include this outcome in a future trial. The ACE-R also proved problematic due to its reliance on language abilities. It will be important to identify a more appropriate way to evaluate specific domains of cognitive functioning for the future trial. One possibility is the Oxford Cognitive Screen,75 which has been designed specifically with a stroke population in mind and is purportedly inclusive for individuals with aphasia and neglect.

Only short-term follow-up was included in this feasibility study. However, a future definitive study would include a longer term 12-month follow-up.

The idea for the HoS intervention originated from a stroke survivor (and coauthor) (RC) who had identified a gap in service provision. Since then, arts and health approaches are beginning to be recognised by policy makers as a useful way to support the health and well-being of communities.39 With NHS pressures and difficulties of accessing formal services,77 our relatively low-cost intervention (which could be as low as £245 per person if delivered at full capacity) offers potential to form part of a comprehensive long-term support pathway to reduce the likelihood of depression following a stroke and increase community access and participation. As we look ahead to a future definitive trial, it will be important to draw on implementation science expertise and to consult with key stakeholders. This will help us to ensure that the HoS intervention, if found to be effective and cost-effective, can be rolled out within existing health service and social care structures and is designed in such a way so as to facilitate its rapid adoption and implementation into practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study sponsor, the Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals (RBCH) NHS Foundation Trust. We would like to acknowledge the Stroke Research Network Rehabilitation Clinical Subgroup for supporting our initial development work and the Research Design Service (South West) for providing invaluable advice on study design, methodology and grantsmanship. We would like to thank Elliot Carter from the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit at Plymouth University for designing and implementing a bespoke web-based randomisation system. We would like to thank the patient and public involvement group and Dr Catherine Ford for providing key input into aspects of study design, outcome measures and study materials. We would also like to thank Dr Susan Hunter, Professor Fiona Jones and Catherine Ovington for agreeing to be members of the Study Steering group. We would like to thank the Stroke Research team at RBCH and the Community Neurorehabilitation teams in Cambridgeshire for their invaluable help with recruitment. We would like to thank all the participants who took part and for their contributions to dissemination activities, including a video, press releases and interviews, art exhibitions held in each centre, and a workshop at the UK National Stroke Forum, and FB and MDBD for the images of their work. Finally we would like to acknowledge and extend our thanks to the National Institute for Health Research, which funded this study through the Research for Patient Benefit programme.

Footnotes

Contributors: CE-H and ST are equal contributors and joint first authors. CE-H (Chief Investigator), FG (Principal Investigator, Cambridge Centre), CL-R and RC were involved in the conception of the study, and CE-H, ST and FG led the design. CE-H, with ST and FG, led the writing of initial grant application and protocol. DJ and FG advised on clinical aspects related to the grant application. PT designed and led the statistical component of the study. EMRM designed and led the economic evaluation, supported by TP. KTG and FR advised on the qualitative aspects. MG and SN refined aspects of the draft protocol. MG coordinated the study on a day-to-day basis. CT and AW organised and administered the blinded assessments. ST and CE-H produced an initial draft of the manuscript. FG, MG, PT and EMRM contributed to the draft and all authors critically reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0212-27054). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. This study is included in the National Institute of Health Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN) portfolio. We were awarded funding from the NIHR-SRN Rehabilitation Clinical Subgroup to bring the research team together and prepare the grant application. FG was supported by NIHR Flexibility and Sustainability Funding via Cambridgeshire Primary Care Trust R&D Department.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Exeter NRES Committee (REC Ref 13/SW/0136) on 30 July 2013. Local research and development approval was granted by the Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust on 6 May 2014. This Trust is the study sponsor. Local research and development approval was granted by Cambridgeshire Community Services NHS Trust on 29 May 2014.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Data sharing statement: Requests for de-identified data should be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Townsend N, Wickramasinghe K, Bhatnagar P, et al. Coronary heart disease statistics. A compendium of health statistics. 2012 Edn. London: British Heart Foundation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health. National stroke strategy. London: Department of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salter K, Hellings C, Foley N, et al. The experience of living with stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:595–602. 10.2340/16501977-0238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hole E, Stubbs B, Roskell C, et al. The patient’s experience of the psychosocial process that influences identity following stroke rehabilitation: a metaethnography. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:1–13. 10.1155/2014/349151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pollock A, St George B, Fenton M, et al. Top ten research priorities relating to life after stroke. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:209 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70029-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Wolfe CD, et al. Natural history, predictors and outcomes of depression after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:14–21. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hackett ML, Pickles K. Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke 2014;9:1017–25. 10.1111/ijs.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cant R. Rehabilitation following a stroke: a participant perspective. Disabil Rehabil 1997;19:297–304. 10.3109/09638289709166542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gracey F, Palmer S, Rous B, et al. "Feeling part of things": personal construction of self after brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2008;18:627–50. 10.1080/09602010802041238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ellis-Hill CS, Horn S. Change in identity and self-concept: a new theoretical approach to recovery following a stroke. Clin Rehabil 2000;14:279–87. 10.1191/026921500671231410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haslam C, Holme A, Haslam SA, et al. Maintaining group memberships: social identity continuity predicts well-being after stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2008;18:671–91. 10.1080/09602010701643449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bulley C, Shiels J, Wilkie K, et al. Carer experiences of life after stroke - a qualitative analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:1406–13. 10.3109/09638280903531238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rigby H, Gubitz G, Eskes G, et al. Caring for stroke survivors: baseline and 1-year determinants of caregiver burden. Int J Stroke 2009;4:152–8. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saka O, McGuire A, Wolfe C. Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing 2009;38:27–32. 10.1093/ageing/afn281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gainotti G, Antonucci G, Marra C, et al. Relation between depression after stroke, antidepressant therapy, and functional recovery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:258–61. 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pohjasvaara T, Vataja R, Leppävuori A, et al. Depression is an independent predictor of poor long-term functional outcome post-stroke. Eur J Neurol 2001;8:315–9. 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bartoli F, Lillia N, Lax A, et al. Depression after stroke and risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke Res Treat 2013;2013:1–11. 10.1155/2013/862978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hackett ML, Anderson CS, House A, et al. Interventions for preventing depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(3):CD003689 10.1002/14651858.CD003689.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salter KL, Foley NC, Zhu L, et al. Prevention of poststroke depression: does prophylactic pharmacotherapy work? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:1243–51. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hackett ML, Anderson CS, House A, et al. Cochrane Stroke Group. Interventions for treating depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;241 Suppl 1:CD003437 10.1002/14651858.CD003437.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-Stroke Depression: A Review. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:221–31 http://doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Villa RF, Ferrari F, Moretti A. Post-stroke depression: Mechanisms and pharmacological treatment. Pharmacol Ther 2018;184:30289–9. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deng L, Sun X, Qiu S, et al. Interventions for management of post-stroke depression: A Bayesian network meta-analysis of 23 randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep 2017;7:16466 10.1038/s41598-017-16663-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watkins CL, Auton MF, Deans CF, et al. Motivational interviewing early after acute stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2007;38:1004–9. 10.1161/01.STR.0000258114.28006.d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watkins CL, Wathan JV, Leathley MJ, et al. The 12-month effects of early motivational interviewing after acute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2011;42:1956–61. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.602227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell PH, Veith RC, Becker KJ, et al. Brief psychosocial–behavioral intervention with antidepressant reduces poststroke depression significantly more than usual care with antidepressant. Stroke 2009;40:3073–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.549808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomas SA, Walker MF, Macniven JA, et al. Communication and Low Mood (CALM): a randomized controlled trial of behavioural therapy for stroke patients with aphasia. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:398–408. 10.1177/0269215512462227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thomas SA, Coates E, das Nair R, et al. Behavioural Activation Therapy for Depression after Stroke (BEADS): a study protocol for a feasibility randomised controlled pilot trial of a psychological intervention for post-stroke depression. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:45 10.1186/s40814-016-0072-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lincoln NB, Flannaghan T. Cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for depression following stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2003;34:111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Knapp P, Campbell Burton CA, Holmes J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;5:CD008860 10.1002/14651858.CD008860.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kneebone II. Stepped psychological care after stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:1836–43. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1107764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harrison M, Ryan T, Gardiner C, et al. Psychological and emotional needs, assessment, and support post-stroke: a multi-perspective qualitative study. Top Stroke Rehabil 2017;24:119–25. 10.1080/10749357.2016.1196908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ellis-Hill C, Payne S, Ward C. Using stroke to explore the life thread model: an alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:150–9. 10.1080/09638280701195462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gracey F, Evans JJ, Malley D. Capturing process and outcome in complex rehabilitation interventions: A "Y-shaped" model. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2009;19:867–90. 10.1080/09602010903027763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilson BA, Gracey F, Evans JJ, et al. ; Neuropsychological rehabilitation. Theory, models, therapy and outcome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Todres L. Being with that: the relevance of embodied understanding for practice. Qual Health Res 2008;18:1566–73. 10.1177/1049732308324249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eilertsen G, Kirkevold M, Bjørk IT. Recovering from a stroke: a longitudinal, qualitative study of older Norwegian women. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:2004–13. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stickley T, Parr H, Atkinson S, et al. Arts, health & wellbeing: reflections on a national seminar series and building a UK research network. Arts Health 2017;9:14–25. 10.1080/17533015.2016.1166142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. All-party parliamentary group on arts, health and wellbeing. The Arts for Health and Wellbeing: Creative Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murray M, Gray R. Health psychology and the arts: a conversation. J Health Psychol 2008;13:147–53. 10.1177/1359105307086704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roe B. Arts for health initiatives: an emerging international agenda and evidence base for older populations. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:1–3. 10.1111/jan.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crone DM, Sumner RC, Baker CM, et al. ’Artlift' arts-on-referral intervention in UK primary care: updated findings from an ongoing observational study. Eur J Public Health 2018;28:404–9. 10.1093/eurpub/cky021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boyce M, Bungay H, Munn-Giddings C, et al. The impact of the arts in healthcare on patients and service users: A critical review. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26:458–73. 10.1111/hsc.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]