Abstract

Objectives

Interest in linking patients with unmet social needs to area-level resources, such as food pantries and employment centres in one’s ZIP code, is growing. However, whether the presence of these resources is associated with better health outcomes is unclear. We sought to determine if area-level resources, defined as organisations that assist individuals with meeting health-related social needs, are associated with lower levels of cardiometabolic risk factors.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

Data were collected in a primary care network in eastern Massachusetts in 2015.

Participants and primary and secondary outcome measures

123 355 participants were included. The primary outcome was body mass index (BMI). The secondary outcomes were systolic blood pressure (SBP), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). All participants were included in BMI analyses. Participants with hypertension were included in SBP analyses. Participants with an indication for cholesterol lowering were included in LDL analyses and participants with diabetes mellitus were included in HbA1c analyses. We used a random forest-based machine-learning algorithm to identify types of resources associated with study outcomes. We then tested the association of ZIP-level selected resource types (three for BMI, two each for SBP and HbA1c analyses and one for LDL analyses) with these outcomes, using multilevel models to account for individual-level, clinic-level and other area-level factors.

Results

Resources associated with lower BMI included more food resources (−0.08 kg/m2 per additional resource, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.03 kg/m2), employment resources (−0.05 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.11 to −0.002 kg/m2) and nutrition resources (−0.07 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.01 kg/m2). No area resources were associated with differences in SBP, LDL or HbA1c.

Conclusions

Access to specific local resources is associated with better BMI. Efforts to link patients to area resources, and to improve the resources landscape within communities, may help reduce BMI and improve population health.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, food insecurity, health disparities, socioeconomic status

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Extensive individual-level and area-level data.

Innovative machine learning methods to overcome issues of collinearity and avoid multiple testing.

Use hierarchical linear modelling to account for data structure.

Cross-sectional study.

No information on use of resources.

Cardiometabolic disease remains the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in the USA.1 Though better control of cardiometabolic risk factors could substantially reduce this morbidity and mortality, individuals with low socioeconomic status (SES) are less likely to achieve recommended goals.2 Among the reasons for this are patient-reported health-related social needs, including food insecurity, housing instability and lack of transportation. These health-related social needs have been associated with higher levels of important cardiometabolic risk factors including increased body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), even after adjusting for factors like race/ethnicity, income and education.3–8 Proposed mechanisms linking health-related social needs to cardiometabolic risk factors include reduced dietary quality, cost-related medication underuse, reduced cognitive ‘bandwidth’ to attend to health and disruptions in clinical care.9–11

Healthcare systems are increasingly interested in working with community partners to help link their patients to local resources, such as food pantries or housing agencies, to help meet health-related social needs.12–16 This approach is exemplified by the Accountable Health Communities initiative from the Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which involves screening for adverse social circumstances and linking those who screen positive to community resources.17 However, there remain significant gaps in knowledge regarding such approaches. Critically, healthcare systems need to know which organisations to partner with, and potentially what types of resources to invest in.18 The specific resources that best address a particular health-related need may not be straightforward. For example, a food pantry could help alleviate food insecurity, but so could employment.

To help address these issues, and inform further interventions, we sought to study associations between area resources and cardiometabolic risk factors in a large primary care network. Our goal was to understand which resource types were associated with improved levels of BMI, SBP, LDL and HbA1c, and to determine whether area resources had stronger associations with cardiometabolic risk factors for conditions that are less amenable to clinical management.

Methods

Setting and study sample

Data for this study came from two primary sources: an asset mapping of community resources and electronic health records. The asset mapping came from the HelpSteps database, a comprehensive asset mapping of area resources in eastern Massachusetts.19 The clinical records came from a primary care network in eastern Massachusetts, a network of 18 primary care practices, including hospital-based, academic and community health centre sites. All adult (age ≥18 years) primary care patients seen between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2015 were included. Data were current on 31 December 2015. The most recent patient address was geocoded for the study. Patients without available addresses were excluded—prior work has shown that only 0.15% of patients in this cohort could not be geocoded.20

The Partners Healthcare Human Research Committee approved this analysis, which entailed use of secondary data without patient contact (Protocol Number: 2017P000964).

Patient and public involvement

The study research question was developed in reference to patient priorities regarding the incorporation of neighbourhood factors that promote health into population health management. Patients were not involved in the design of the study or in recruitment. We plan to disseminate study results via open-access publication.

Area resources

HelpSteps (www.helpsteps.com) is a web and mobile screening and referral system for social needs. Originally launched in 2010, the system uses a database of social services throughout the greater Boston area to connect families to appropriate services. The database is maintained in collaboration between Boston Children’s Hospital and the Mayor’s Health Line at the Boston Public Health Commission. Every agency is contacted at least once per year to maintain the accuracy of the data and to grow the database. HelpSteps contains information on area resources across 16 non-mutually exclusive domains: health, housing, food employment, violence, safety, substance abuse, mental health, education, parenting, nutrition, after school, sexual health, transportation, diabetes and care transitions. An example of organisations that would be in the food domain are food pantries. The employment domain would consist of job placement or job training services. And the nutrition domain would include organisations that provide food counselling. Agencies providing multiple resources could be included in more than one domain. Because individual-level data for this study came from 2015, we used information from HelpSteps that was current as of 2015. For this study, ‘area resources’ are defined as the number of organisations found in the HelpSteps database providing assistance for a given domain and within a given geographic area.

After geocoding the addresses for both individuals and the area resource organisation, we created counts, for each individual, of how many resources for each domain were within the same geographic area as they were. We did this at four geographic levels in roughly increasing order of size: census tract (using US Census 2010 boundaries), ZIP code tabulation area (which we refer to throughout this paper as ‘ZIP’ level, owing to common use of the term, again using US Census 2010 boundaries), ‘neighbourhood’ (eg, Allston, Roxbury, a designation based on Boston city planning that may better capture actual movement patterns) and county.

Clinical outcomes

To assess clinical outcomes, we calculated the mean of all values recorded in 2015 from individual’s electronic health record for the following measurements: BMI (in kg/m2), SBP (in mm Hg), LDL cholesterol (in mg/dL) and HbA1c (%). All values were obtained in the process of usual care.

Covariates

To account for possible confounding of the association between area resources and health outcomes, we collected the following variables from the electronic health record: age (years), gender (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic or Asian/other/multi), education (less than high school diploma, high school diploma [including General Educational Development certificate] or greater than high school diploma), insurance (commercial, Medicare, Medicaid [including dual-eligibles] and uninsured/self-pay), number of clinic visits in 2015, primary language (English vs other), connectedness to their primary care clinic using previously validated algorithm21 and comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity score, and individual indicators of depression, hypertension, coronary heart disease, osteoarthritis and diabetes). To account for area-level differences from factors other than resources, we used data from the US Census’ American Community Survey (5-year estimates 2010–2015) and the USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas: median household income, percent living in poverty, ‘food desert’ status (low income, low food access census tract at 1/2 mile in urban areas and 10 miles in rural areas), unemployment rate, proportion of the area population living in group quarters (eg, those living in a nursing facility unlikely to be exposed to area-level conditions), vehicle access and housing segregation.22 23

Statistical analysis

In this study, we wanted to evaluate the relationship between many resources types and cardiometabolic risk factors. A secondary goal of our study was to help understand the relationship that specific geographic levels and resource types had with clinical outcomes. Because the nested structure of our data violate the statistical independence assumption that underlies parametric, regression-based variable selection approaches (such as forward, backward or stepwise selection), and to avoid multiple hypothesis testing that may lead to the identification of spurious associations, we employed a non-parametric machine learning technique called variable selecting using random forest (VSURF) to screen through variables in the derivation set.24 25 This was done using a derivation data set, which consisted of a random partition of the entire data set. Finally, we used multilevel modelling in the test set (not used in the derivation stage) to test a small number of candidate variables identified by VSURF as being most important to explaining variations in the derivation set. VSRUF is described in more detail in technical online supplementary appendix and efigure 1.

bmjopen-2018-025281supp001.pdf (1,016KB, pdf)

Multilevel modelling

In the test data set, we fit multilevel linear mixed models to test the association between variables identified in the VSURF step and the outcome of interest. The BMI model included all study participants. The SBP model included those with a diagnosis of hypertension. The LDL model included those with common diagnoses (hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure) where LDL lowering is most beneficial. The HbA1c models included those with a diagnosis of diabetes. The models used fixed effects to adjust for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, insurance, number of clinic visits, language, clinic connectedness, comorbidity and census tract level median household income, poverty rates, ‘food desert’ status, unemployment, numbers living in group quarters, vehicle access and segregation. To account for clustering within practices, we included a practice-level random effects term. To account for area-level clustering, we used a ZIP-level random effects term. These were fit as crossed effects models (ie, we did not nest practices within ZIP codes) to allow for the fact that patients are often seen in practices outside of their ZIP code of residence.

Falsification tests

To reduce the possibility that observed associations due to other unmeasured characteristics of the area, rather than the specific area resource tested, we also conducted falsification analyses. To do this, we used the same modelling approach as above, but tested for the association between area afterschool resources for children and the outcome of interest. Our reasoning was that, since there was unlikely to be any direct effect of afterschool resources for children on adult BMI, any observed association would reflect unmeasured area characteristics not appropriately adjusted for in our model (such as high levels of civic engagement or community organisation, or other beneficial resources).

Variations in clinical management

To help explore whether variations in the intensity of clinical management could explain whether community resources were associated with health outcomes, we also used the above modelling approach to test whether area resources were associated with SBP in those without a diagnosis of hypertension. The primary care network in the study has a quality improvement programme that emphasises the importance of SBP, LDL and HbA1c control in appropriate clinical populations. Since BMI (in any population) and SBP control in those without a diagnosis of hypertension are not included in these programmes, we reasoned that area resources may be more important when clinicians are not intensively attempting to impact an outcome. We focused on BMI and SBP among those without hypertension for this because BMI and SBP are routinely measured at all practice visits for all patients.

Because of its mechanistically plausible relationship with BMI, we used the association between ZIP-level food resources and BMI as the primary outcome, with secondary analyses being the associations between other VSURF selected area resources and clinical outcomes.

Robustness checks

In addition to the main analyses, we conducted a series of robustness checks that examined whether different specifications of resources in the area (eg, resources per capita or resources per capita living in poverty) or different functional forms (eg, including polynomial terms or using splines) would alter the observed associations between area-level resources and outcomes. We also conducted analyses restricted to those with indicators of lower SES (high school diploma or lower educational attainment, living in a ZIP where >15% of individuals are in poverty) to ensure the results were applicable to those most likely to use the resources studied.

A p value of <0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. Analyses were conducted in SAS V.9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA), Stata 14 (College Station, Texas, USA) and R V.3.3.4 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Overall, 123 355 participants were included in the study. All participants were eligible for BMI analyses. Based on inclusion criteria, 43 509 were included in the hypertension analyses, 46 940 were included in the LDL analyses and 13 127 were included in the diabetes analyses. Demographic characteristics of the overall sample are presented in table 1. Demographic characteristics of the samples used in the hypertension, LDL cholesterol and diabetes analyses are presented in online supplementary eTables 1–3. Overall, the mean age was 52.4 (SD 16.9) years, the sample was 41.5% men, 82.1% non-Hispanic white, 5.8% non-Hispanic black and 6.5% Hispanic. The median number of years participants followed in our network was 9 (IQR 3, 10), and the median number change of address per year followed was 0.1 (IQR 0.1, 0.25), suggesting that participants resided at their current address for the majority of their time in our network.

Table 1.

Demographics of study sample

| n=123 355 | |

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Age | 52.42 (16.89) |

| Male | 51 665 (41.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian/Multi/Other | 6880 (5.6) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7203 (5.8) |

| Hispanic | 8039 (6.5) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 101 233 (82.1) |

| Education | |

| College or > | 56 302 (45.6) |

| High school diploma | 36 572 (29.6) |

| Less than high school diploma | 18 051 (14.6) |

| Unknown/Declined | 12 430 (10.1) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 75 787 (61.4) |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 8602 (7.0) |

| Medicaid | 20 934 (17.0) |

| Medicare | 17 911 (14.5) |

| Self-pay | 121 (0.1) |

| English is primary anguage | 112 720 (91.4) |

| History of hypertension | 43 509 (35.3) |

| History of coronary heart disease | 9275 (7.5) |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 13 127 (10.6) |

| History of depression | 10 300 (8.3) |

| History of osteoarthritis | 23 707 (19.2) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.72 (2.23) |

| Clinic visits | 6.57 (5.77) |

| Clinic connectedness | |

| Connected to specific physician | 80 345 (65.1) |

| Connected to specific practice | 34 018 (27.6) |

| Other | 8992 (7.3) |

| Lives in urban area | 91 095 (96.4) |

| ZIP-level unemployment rate, % | 4.71 (1.60) |

| ZIP-level median household Income, $ | 82 309.16 (31758.79) |

| ZIP-level poverty rate, % | 8.70 (6.72) |

| ZIP-level segregation* | 69.51 (21.05) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.84 (6.24) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 124.36 (14.96) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 110.83 (39.95) |

| Haemoglobin A1c, % | 5.94 (1.22) |

*Segregation index is a dissimilarity measure of the extent to which groups other than non-Hispanic whites are distributed like non-Hispanic whites. 0 represents complete integration and 100 represents complete segregation.

LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

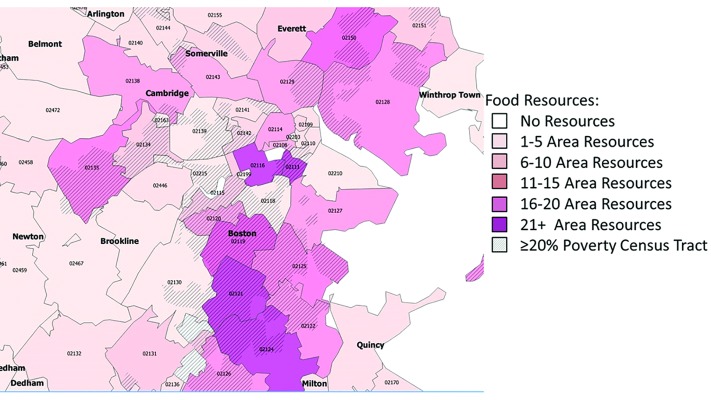

In general, individuals living in areas with more resources had lower educational attainment and higher rates of Medicaid insurance coverage (online supplementary eTable 4). Maps depicting the distribution of the resources are presented in figure 1 and online supplementary eFigures 2–3.

Figure 1.

Food resource density by ZIP.

The mean BMI in the sample was 27.8 (SD 6.2) kg/m2. In the hypertension analyses, the mean BP was 131.6 (SD 15.8) mm Hg. In the LDL analyses, the mean LDL was 102.9 (SD 39.8) mg/dL, and in the diabetes analyses the mean HbA1c was 7.1 (SD 1.5)%.

Among geographic levels assessed, all resources selected were at the ZIP level (table 2). For the BMI analyses, the selected resources were ZIP-level food resources, ZIP-level employment resources and ZIP-level nutrition resources. For hypertension analyses, the selected resources were ZIP housing and ZIP nutrition resources. For LDL analyses, the only selected resource was ZIP nutrition resources. For diabetes analyses, the selected resources were ZIP mental health and ZIP substance use resources.

Table 2.

Distribution of the number of resources in the selected resource categories

| Resource* | Minimum | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | 90th percentile | 95th percentile | Maximum |

| BMI Analyses | |||||||

| Food | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 27 |

| Employment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 18 | 33 |

| Nutrition | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 21 |

| Hypertension analyses | |||||||

| Housing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 23 |

| Nutrition | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 21 |

| LDL analyses | |||||||

| Nutrition | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 21 |

| Diabetes analyses | |||||||

| Mental health | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 21 |

| Substance use resources | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 23 |

*All resources assessed at ZIP level; table represents counts of each resource type.

BMI, body mass index; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

For the BMI analyses, we tested the association between selected resources and BMI, adjusting for the factors described in the statistical analysis section, and accounting for clustering at the clinic and ZIP level with multilevel linear mixed models. We found that resources associated with lower BMI included more food resources (−0.08 kg/m2 per additional resource, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.03 kg/m2, p=0.001), employment resources (−0.05 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.11 to −0.002 kg/m2, p=0.04) and nutrition resources (−0.07 kg/m2, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.01 kg/m2, p=0.02) (full models for these and all robustness checks in online supplementary eappendix table 5-16). Table 3 compares mean BMI and obesity prevalence at selected numbers of resources, adjusted for the other factors in the model. For example, the mean BMI in neighbourhoods with the median (0) number of food resources was 27.8 kg/m2, while the mean BMI in neighbourhoods in the 75th percentile (three resources) was 27.5 kg/m2 and the 90th percentile (eight resources) was 27.1 kg/m2. Falsification tests found the expected lack of association between afterschool resources and BMI (p=0.67).

Table 3.

Estimated BMI, in kg/m2, by resource level

| ZIP-level food resources | |

| 50th percentile | 27.78 |

| 75th percentile | 27.53 |

| 90th percentile | 27.11 |

| 95th percentile | 26.85 |

| ZIP-level employment resources | |

| 50th percentile | 27.78 |

| 75th percentile | 27.56 |

| 90th percentile | 27.07 |

| 95th percentile | 26.80 |

| ZIP-level nutrition resources | |

| 50th percentile | 27.75 |

| 75th percentile | 27.54 |

| 90th percentile | 27.32 |

| 95th percentile | 26.89 |

Estimates created using least-squares means from fitted multilevel models. The models used fixed effects to adjust for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, insurance, number of clinic visits, language, clinic connectedness, comorbidity and census tract level median household income, poverty rates, ‘food desert’ status, unemployment, numbers living in group quarters, vehicle access and segregation. To account for clustering within practices, we included a practice-level random effects term. To account for area-level clustering, we used a ZIP-level random effects term. These were fit as crossed effects models (ie, we did not nest practices within ZIP codes) to allow for the fact that patients are often seen in practices outside of their ZIP code of residence.

BMI, body mass index.

Robustness checks found that our results did not vary substantially with other specifications of area-level resources (online supplementary eTables 5–7).

In the hypertension analyses, neither housing resources (−0.05 mm Hg per additional resource, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.06 mm Hg, p=0.41) nor nutrition resources (0.01 mm Hg, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.16 mm Hg, p=0.87) were associated with SBP after adjustment for individual-level and area-level characteristics. In LDL analyses, nutrition resources (0.10 mg/dL per additional resource, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.55 mg/dL, p=0.67) were not associated with LDL cholesterol in adjusted models. In diabetes analyses, neither substance abuse resources (−0.003% per additional resource, 95% CI −0.03% to 0.02%, p=0.86) nor mental health resources were associated with HbA1c (−0.003%, 95% CI −0.03% to 0.02%, p=0.76).

In analyses looking at SBP among those without a diagnosis of hypertension (ie, those with no reason for clinical management of blood pressure), food resources were associated with lower SBP in linear mixed models adjusted for the same factors as above (−0.08 mm Hg per additional resource, 95% CI −0.15 to −0.01 mm Hg, p=0.03). Mean SBP was approximately 1 mm Hg lower at the 95th percentile (118.9 mm Hg) of food resources compared with the 50th percentile (119.8 mm Hg).

Full models for all analyses are presented in online supplementary eTables 8–16.

Discussion

This study assessed the relationship among area resources and cardiometabolic risk factors. We found that increasing numbers of food, employment and nutrition resources was associated with lower BMI and lower SBP among those without hypertension. The magnitude of the difference was meaningful at the population level, as the 0.7 kg/m2 difference in BMI between individuals in a well-resourced versus poorly resourced ZIP is similar to the 0.6 increase kg/m2 in BMI in the overall US population from 2006 to 2016.26

Conversely, we found that area resources were not associated with SBP among those with hypertension, LDL cholesterol among those with an indication for LDL lowering or haemoglobin A1c among those with diabetes. This suggests that the relationship between area resources and cardiometabolic risk factors may vary based on whether these factors are targets of intensive clinical management.

This study enhances our knowledge regarding the association of area-level factors and cardiometabolic risk factors. Prior studies have consistently found that adverse area-level factors, such as poverty, are associated with increased cardiometabolic risk, even when adjusting for individual-level factors, such as income.2 27–29 However, we did not know whether the presence of area resources that might plausibly support health, such as food and nutrition resources, would be associated with lower cardiometabolic risk.

The positive and negative associations between community resources and cardiometabolic risk factors may have important public health implications. The association between increased area resources and lower BMI suggests that efforts to help link patients to community resources, and to help improve the resources landscape within communities, may be a successful strategy for improving population health, particularly for risk factors such as BMI where clinical management may not be prioritised.13 14 30 This is reinforced by the finding that SBP, among those without hypertension, is lower in those living in areas with more resources. Since SBP does not come under clinical management for those without hypertension, this finding supports the potential for area resources to impact population health, and is consistent with guidelines that recommend lifestyle, rather than pharmacological, approaches to prehypertension treatment.31 Future work in this area should investigate whether interventions that link individuals to area resources show clinical benefits.

Our finding should be interpreted in light of several limitations. We did not have access to data regarding use of the resources. This means that we do not know whether individuals made use of the resources in their community. In light of this, the association between ZIP-level resources and outcomes could be viewed analogously to an ‘encouragement design’ intervention. This means that the association estimated in this study is likely different than the association that would be estimated if analysing those who were known to use the resource. That association is clearly of policy interest, and should be examined in future work. While we adjusted for several individual-level and area-level SES indicators in order to capture the multidimensional nature of SES and, thus, reduce confounding, it is possible that residual confounding, owing to unmeasured characteristics, exists, which would tend to reduce the observed associations between area resources and outcomes. Additional unmeasured covariates that could affect the observed associations include local culture, and the quality of the resources available. Devising methodology to determine the quality of the services provided to help meet health-related social needs is pressing, and will be an important direction for future investigation. Next, our study was cross-sectional, and thus we cannot establish time ordering between the exposure and the cardiometabolic outcomes. However, we think it is less likely that lower BMI would drive individuals into areas with more resources than vice versa, as areas with higher resources tended to have other adverse features, such as lower income and higher poverty, which are likely more salient considerations for those choosing where to live. Finally, because of the relatively high residential stability within this primary care population, we only examined the association between current area of residence and the study outcomes. However, for those who do move, this could lead to misclassification, which would tend to bias results to the null. These limitations are balanced by several strengths. We had access to a detailed mapping of area resources, along with detailed individual-level health information. Further, in addition to the multilevel framework we used, the use of falsification tests demonstrated that unadjusted area-level factors are not likely to explain the observed results.

In summary, ZIP-level food, employment and nutrition resources were associated with BMI differences that were clinically meaningfully and statistically significant. Further, the association between area resources and cardiometabolic risk factors differed based on the specific risk factor. Investing in area resources and linkage programmes may be an important way to help reduce cardiometabolic risk for vulnerable individuals, especially for situations not under intensive clinical management.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SAB conducted the data analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and is the guarantor of the article. SAB, EWF and SJA conceived the study. GR assisted with data analysis. SB, AV and GR contributed to interpretation of results and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual context. All authors (SAB, SB, AV, GR, EWF, and SJA) read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers DP2MD010478 (SB), U54MD010724 (SB), and K23DK109200 (SAB).

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Statistical code will be available concurrent with publication from http://saberkowitz.web.unc.edu/statistical-code/. Owing to privacy concerns, study data cannot be made publicly available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths and mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm (Accessed 19th Mar 2018).

- 2. Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2015;132:873–98. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berkowitz SA, Baggett TP, Wexler DJ, et al. Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3093–9. 10.2337/dc13-0570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:257–65. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz TSZ, Meigs JB, et al. Trends in food insecurity for adults with cardiometabolic disease in the United States: 2005-2012. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179172 10.1371/journal.pone.0179172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr 2010;140:304–10. 10.3945/jn.109.112573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baer TE, Scherer EA, Richmond TK, et al. Food insecurity, weight status, and perceived nutritional and exercise barriers in an urban youth population. Clin Pediatr 2018;57:152–60. 10.1177/0009922817693301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morales ME, Berkowitz SA. The relationship between food insecurity, dietary patterns, and obesity. Curr Nutr Rep 2016;5:54–60. 10.1007/s13668-016-0153-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:6–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1000072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med 2014;127:303–10. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keene DE, Guo M, Murillo S. "That wasn’t really a place to worry about diabetes": housing access and diabetes self-management among low-income adults. Soc Sci Med 2018;197:71–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hassan A, Blood EA, Pikcilingis A, et al. Youths' health-related social problems: concerns often overlooked during the medical visit. J Adolesc Health 2013;53:265–71. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hassan A, Scherer EA, Pikcilingis A, et al. Improving social determinants of health: effectiveness of a web-based intervention. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:822–31. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, et al. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:244–52. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:719–29. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e162521 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, et al. Accountable health communities-addressing social needs through medicare and medicaid. N Engl J Med 2016;374:8–11. 10.1056/NEJMp1512532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bauer SR, Monuteaux MC, Fleegler EW. Geographic disparities in access to agencies providing income-related social services. J Urban Health 2015;92:853–63. 10.1007/s11524-015-9971-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fleegler E J, Bottino C, Pikcilingis A, et al. Referral system collaboration between public health and medical systems: a population health case report. Natl Acad Med Perspect Popul Health Case Rep 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, et al. Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: results from a primary care network. Health Serv Res 2015;50:398–417. 10.1111/1475-6773.12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atlas SJ, Grant RW, Ferris TG, et al. Patient-physician connectedness and quality of primary care. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:325–35. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-5-200903030-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. USDA. USDA Food access research atlas documentation. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation/ (Accessed 11th Aug 2017).

- 23. Napierala J, Denton N. Measuring Residential Segregation With the ACS: how the margin of error affects the dissimilarity index. Demography 2017;54:285–309. 10.1007/s13524-016-0545-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Genuer R, Poggi J-M, Tuleau-Malot C. Variable selection using random forests. Pattern Recognit Lett 2010;31:2225–36. 10.1016/j.patrec.2010.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Genuer R, Poggi J-M, Tuleau-Malot C. VSURF: an r package for variable selection using random forests. R J 2015;7:19–33. 10.32614/RJ-2015-018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1377–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomas AJ, Eberly LE, Davey Smith G, et al. Race/ethnicity, income, major risk factors, and cardiovascular disease mortality. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1417–23. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1783–9. 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kelli HM, Hammadah M, Ahmed H, et al. Association between living in food deserts and cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:e003532 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135:e296–304. 10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a Report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:1269–324. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025281supp001.pdf (1,016KB, pdf)