Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the prevalence and distribution in the comorbidity of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among the adult population in Bangladesh by measures of socioeconomic status (SES).

Design

This was a cross-sectional study.

Setting

This study used Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011 data.

Participants

Total 8763 individuals aged ≥35 years were included.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN) and overweight/obesity. The study further assesses factors (in particular SES) associated with these comorbidities (DM, HTN and overweight/obesity).

Results

Of 8763 adults, 12% had DM, 27% HTN and 22% were overweight/obese (body mass index ≥23 kg/m2). Just over 1% of the sample had all three conditions, 3% had both DM and HTN, 3% DM and overweight/obesity and 7% HTN and overweight/obesity. DM, HTN and overweight/obesity were more prevalent those who had higher education, were non-manual workers, were in the richer to richest SES and lived in urban settings. Individuals in higher SES groups were also more likely to suffer from comorbidities. In the multivariable analysis, it was found that individual belonging to the richest wealth quintile had the highest odds of having HTN (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.49, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.72), DM (AOR 1.63, 95% CI 1.25 to 2.14) and overweight/obesity (AOR 4.3, 95% CI 3.32 to 5.57).

Conclusions

In contrast to more affluent countries, individuals with NCDs risk factors and comorbidities are more common in higher SES individuals. Public health approaches must consider this social patterning in tackling NCDs in the country.

Keywords: overweight, diabetes, hypertension, non-communicable disease, socioeconomic status, Bangladesh

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The biggest strength of the study is that it used a large dataset nationally representative of the Bangladesh population, collected using measures that have been designed and validated through previous data collections in the country.

Data collection included clinical measures of blood pressure, blood glucose concentration, body weight and height collected by a health technician.

The main weakness of the study is that it is cross-sectional in nature, meaning that only associations can be inferred and causality cannot be determined.

Introduction

According to the Global Burden of Disease report, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death worldwide1–3 and that 80% of this NCDs mortality actually occurs in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).4–6 Similarly, the 2014 NCDs global status report showed that of 58 million deaths that occurred globally in 2012, 38 million—almost two-thirds—were due to NCDs, with these deaths most due to the four most common NCDs: cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic lung diseases.7 In addition, the report showed that more than 40% of these deaths (16 million) occurred were in individuals under the age of 70 years, often referred to as premature deaths.7 Deaths at younger ages may be a greater demonstration of its burden, as many consider them preventable. It is alarming, therefore, that the majority of premature deaths (82%) occur in LMICs, with this problem likely to increase if appropriate preventative actions are not taken at a population level.

Like many LMICs, Bangladesh is undergoing rapid urbanisation with changing patterns of diseases among the population,8 9 with some suggesting that the country is at an advanced phase of the third stage of the epidemiological transition, with deaths from NCDs expected to increase rapidly in the coming years.10 This increasing mortality from NCDs in the country is supported by high prevalence of the medical risk factors associated with NCDs. A recent WHO STEPS survey in Bangladesh reported that 21% of the population had hypertension (HTN), 26% were overweight and 5% had documented DM.11

These high prevalence figures raise concerns of comorbidity, in which individuals suffer from more than one of the risk factors at a time, with this thought to be highly predictive of end point diseases, disability and death.12 There is evidence of comorbidity risk for factors including obesity, DM and HTN, predominantly coming from industrialised countries13–15 and LMICs16–18; however, evidence on NCDs comorbidity scants in Bangladesh. This is important as the patterning of NCDs is not uniform across countries of different income classification, with a higher prevalence of some NCDs risk factors, such as DM, found in higher socioeconomic groups in many studies in LMICs, contradicting those from higher income countries.19

With the development of a double burden from both overnutrition and undernutrition in these LMICs, understanding comorbidity and their correlates is important if we are to develop NCDs preventative policies contextualised for these countries. Despite the availability of nationwide survey data in Bangladesh, the prevalence, and in particular, the comorbidity of NCDs medical risk factors remains unmapped. This understanding of the burden and patterning of NCDs and their risk factors is important if Bangladesh is able to meet the Sustainable Development Goals target of reducing premature death from NCDs by one-third by 2030.20

This study used 2011 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) data to estimate the prevalence and pattern of NCDs risk factors and comorbidity among the general population aged 35 years and older, as well as determining their sociodemographic patterning and possible predictors of comorbidity.

Methods

Study design

This study used data from the 2011 BDHS. The 2011 BDHS is a cross-sectional nationally representative survey that was conducted between July and December 2011 through the collaboration of the National Institute of Population Research and Training, ICF International (USA), and Mitra and Associates. Participants in the BDHS were selected using probability sampling based on a two-stage cluster sample of households, and stratified by rural and urban areas in the seven administrative regions of Bangladesh. The detailed protocol and methods have been published previously.21 In brief, 17 500 households were surveyed, of which one in three households were randomly selected for biomarker measurement (blood glucose, blood pressure). All men and women age 35 years and above were eligible for the biomarker measures, with these collected from a final sample of 8835 individuals (male: 4524, female: 4311)22. We included 8763 cases in our analytical sample, after excluding cases with missing values.

Measurements of outcomes

A data collection team, including a health technician, measured blood pressure, blood glucose concentration, body weight and height using standard methods.21 DM was defined as a fasting blood glucose (FBG) level greater than or equal to 7.0 mmol/L or self-reported DM medication use23. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). We used Asian-specific BMI cut-offs to define underweight as ≥18.5 kg/m2 and overweight and obese (higher BMI) as ≥23 kg/m2.24 HTN was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg or self-reported antihypertensive medication use during the survey.21 We then categorised comorbidity into four groups such as respondents having DM and HTN (group A), DM and overweight/obesity(group B), HTN and overweight/obesity (group C) and group D in which individuals had all three conditions (DM, HTN and overweight/obesity).

Sociodemographic factors

We categorised age as older (defined as 56 years and above) and younger (35–55 years).25 Education status was characterised into four levels: (1) no education and preschool education, (2) primary, (3) secondary and (4) college or higher. We categorised occupation as manual or non-manual worker and used principal component analysis to determine a wealth index was as described in the BDHS 2011 report.21 Place of residence (urban and rural) and sex (male and female) were also included as important factors.

Statistical analysis

HTN, DM, overweight/obesity and all possible combinations of the comorbidity conditions were the main outcomes of interest. For analysis purposes, all outcomes were dichotomised into persons with or without the risk factor. Sex, age, education, occupation, wealth index and place of residence were included in analysis as independent variables. We calculated the weighted prevalence of DM, HTN, overweight/obesity through percentage in the sample and used modified Poisson regression (PR) models with robust error variance to calculate prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CI for DM, HTN and overweight. These analyses were adjusted for cluster and sample weight and were done using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM, Released 2012.). We also calculated the power to assess whether the existing sample size is enough for performing the multivariable regression models. The variables sex, age, education, occupation are control variables and not of primary research interest. The variable wealth index is our primary interest to assess the association with the joint estimates of NCDs. We have converted the log (PR) to calculate the effect size by the formula d=log (PR)×(√3/π). The primary research hypothesis was to test the wealth index from poorer to richest groups with the joint estimate of NCDs in the regression equation. We have considered the power 0.90, level of significance 0.05, calculated effect size from PR and then we get the estimated sample size for each model of each outcome which covers the existing sample size of our analysis. We have performed the power analysis using G*Power software. The authors followed the guidelines outlined in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement in writing the manuscript (online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2018-025538supp001.pdf (642.2KB, pdf)

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the study.

Findings

The study population (n=8763) comprised 51% males, around 56% were 56 years of age or older, 62% reported no education, 25% were in manual employment and 76% lived in rural locations (table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population

| Variables | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4480 | 51.13 |

| Female | 4283 | 48.87 |

| Age | ||

| Younger | 3603 | 55.77 |

| Older | 2858 | 44.23 |

| Education | ||

| College or higher | 592 | 6.75 |

| Secondary | 1129 | 12.88 |

| Primary | 1634 | 18.64 |

| No education, preschool | 5409 | 61.72 |

| Occupation | ||

| Manual | 2142 | 24.89 |

| Non-manual | 6464 | 75.11 |

| Wealth index | ||

| Poorest | 1696 | 19.36 |

| Poorer | 1671 | 19.06 |

| Middle | 1692 | 19.31 |

| Richer | 1784 | 20.35 |

| Richest | 1921 | 21.92 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Rural | 6623 | 75.58 |

| Urban | 2140 | 24.42 |

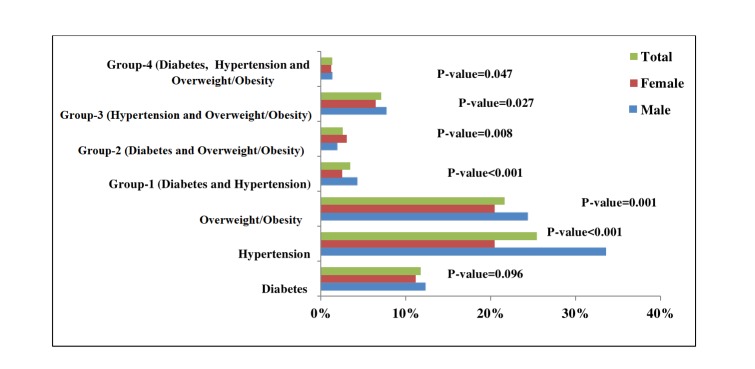

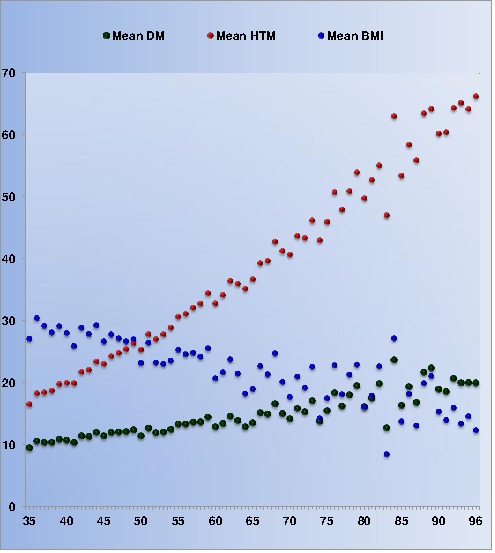

Among the sample, 12% had DM, 27% had HTN and 22% were classified as overweight/obesity (BMI ≥23 kg/m2). The probability of having DM and HTN increased by increasing age group, while the probability of being overweight/obesity was higher in the younger age group (figure 1). Prevalence of all these conditions was higher among males than females. The prevalence of group A (DM and HTN, n=270) and group B (DM and overweight/obesity, n=191) comorbidities was 3%, while 7% of the sample had group C comorbidity (HTN and overweight/obesity t, n=513). One per cent) of the sample had all three conditions (DM, HTN and overweight/obesity=104). Prevalence of all groups of comorbidity was higher in males than females, except for group B (DM and overweight/obesity) (figure 2). The prevalence of individual conditions and all comorbidities was higher among older individuals, those with a ‘college or higher’ education, ‘non-manual’ workers, people in the richest quintile for wealth index and those living in urban environments (table 2).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot between age with blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and BMI. BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, overweight and comorbidity by sex among Bangladeshi adults.

Table 2.

Weighted prevalence of individual conditions and comorbidities by characteristics

| Variables | Diabetes (%, 95% CI) |

Hypertension (%, 95% CI) |

Overweight/Obesity (%, 95% CI) |

Group-A (%, 95% CI) (diabetes and hypertension) |

Group-B (%, 95% CI) (diabetes and overweight/obesity) |

Group-C (%, 95% CI) (hypertension and overweight/obesity) |

Group-D (%, 95% CI) (diabetes, hypertension and overweight/obesity |

| Age | |||||||

| Younger | 10.2 (9 to 11.5) | 19.2 (17.4 to 21.1) | 24.6 (22.7 to 26.5) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.9) | 3.5 (2.8 to 4.4) | 8.5 (7.4 to 9.8) | 1.4 (1 to 2) |

| Older | 14.7 (12.9 to 16.7) | 38.7 (36.3 to 41.2) | 18 (16.2 to 20) | 5 (4.1 to 6.1) | 3.3 (2.5 to 4.3) | 10.1 (8.8 to 11.5) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.2) |

| Education | |||||||

| Higher | 22 (18.7 to 25.8) | 33.1 (29.4 to 37) | 53.9 (49 to 58.8) | 7.7 (5.6 to 10.6) | 8.6 (6.4 to 11.4) | 17.5 (14.5 to 21) | 4.3 (2.8 to 6.5) |

| Secondary | 13.3 (11.4 to 15.4) | 27.5 (24.9 to 30.3) | 29.7 (26.4 to 33.2) | 4.8 (3.7 to 6.1) | 3.6 (2.6 to 4.8) | 7.8 (6.3 to 9.8) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9) |

| Primary | 11.6 (10.2 to 13.3) | 23.6 (21.4 to 25.9) | 21 (18.6 to 23.6) | 3.2 (2.5 to 4.3) | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.4) | 7.1 (5.8 to 8.5) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) |

| No education, preschool | 9.5 (8.3 to 10.8) | 28 (26.1 to 30) | 13.3 (11.9 to 15) | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.1) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.8) | 5.2 (4.4 to 6.1) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Occupation | |||||||

| Manual | 6.8 (5.6 to 8.2) | 14.4 (12.7 to 16.3) | 10.5 (9.2 to 12.1) | 1 (0.6 to 1.6) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) | 2.7 (2 to 3.5) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) |

| Non-manual | 13.4 (12.3 to 14.6) | 31.5 (29.8 to 33.1) | 27.7 (25.8 to 29.6) | 4.3 (3.7 to 5) | 3.2 (2.6 to 3.9) | 8.8 (7.9 to 9.8) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) |

| Wealth index | |||||||

| Poorest | 8.4 (6.9 to 10.2) | 20.6 (18.3 to 23.1) | 6.6 (5.2 to 8.5) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.4) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.3) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.1) |

| Poorer | 8.1 (6.4 to 10.2) | 22.6 (20 to 25.4) | 10.4 (8.6 to 12.7) | 1.7 (1 to 2.8) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.2) | 2.9 (2.1 to 4) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.9) |

| Middle | 8.2 (6.7 to 9.9) | 24.2 (21.9 to 26.6) | 14.6 (12.3 to 17.2) | 2 (1.3 to 2.9) | 1 (0.5 to 1.8) | 3.4 (2.5 to 4.7) | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.1) |

| Richer | 11.8 (9.9 to 14) | 28.8 (26.4 to 31.3) | 27.8 (24.7 to 31.1) | 3.5 (2.6 to 4.7) | 2.5 (1.8 to 3.5) | 9.3 (7.9 to 11) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) |

| Richest | 20.8 (18.6 to 23.3) | 38.6 (36.3 to 41.1) | 47.9 (44.8 to 51) | 8.3 (6.8 to 10) | 8 (6.5 to 9.8) | 17.6 (15.6 to 19.7) | 4.3 (3.2 to 5.7) |

| Place of residence | |||||||

| Urban | 16.5 (14.6 to 18.5) | 33.3 (31.1 to 35.5) | 37.4 (34.3 to 40.7) | 6 (4.9 to 7.3) | 5.5 (4.4 to 6.8) | 12.9 (11.3 to 14.6) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.2) |

| Rural | 10.3 (9.3 to 11.3) | 25.3 (23.5 to 27.1) | 17.1 (15.6 to 18.6) | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.3) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) | 5.4 (4.7 to 6.3) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) |

The PR, from modified Poison regression models, of HTN, DM and overweight/obesity was significantly higher among those who had completed higher education, those living in urban areas, non-manual workers and those in the richer to richest socioeconomic status (SES). Although there were no sex disparities for DM, HTN and overweight/obesity were higher among males. Overweight/obesity was the only condition that was significantly higher among younger participants (table 3).

Table 3.

Modified Poisson regression models showing prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs for diabetes, hypertension and overweight/obesity by demographic characteristics among Bangladeshi adults

| Variables | Diabetes | Hypertension | Overweight/obesity |

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.89 (0.74 to 1.08) | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.65)* | 0.7 (0.62 to 0.79)* |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Age† | |||

| Older | 1.48 (1.26 to 1.73)* | 1.72 (1.56 to 1.88)* | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.83)* |

| Younger | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Education | |||

| College or higher | 1.71 (1.32 to 2.23)* | 1.36 (1.15 to 1.61)* | 2.11 (1.79 to 2.5)* |

| Secondary | 1.16 (0.92 to 1.48) | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.28) | 1.56 (1.34 to 1.83)* |

| Primary | 1.21 (0.99 to 1.48) | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.08) | 1.29 (1.12 to 1.5)* |

| No education, preschool | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Occupation | |||

| Non-manual‡ | 1.54 (1.24 to 1.91)* | 1.46 (1.28 to 1.68)* | 1.62 (1.39 to 1.90)* |

| Manual | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Wealth index | |||

| Richest | 1.63 (1.25 to 2.14)* | 1.49 (1.29 to 1.72)* | 4.3 (3.32 to 5.57)* |

| Richer | 1.04 (0.79 to 1.35) | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.42)* | 3.07 (2.39 to 3.95)* |

| Middle | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.03) | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.21) | 1.8 (1.38 to 2.36)* |

| Poorer | 0.94 (0.71 to 1.24) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.16) | 1.45 (1.09 to 1.92)* |

| Poorest | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | 1.1 (0.92 to 1.32) | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.15) | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.21) |

| Rural | Ref | Ref | Ref |

In univariate PR models, those in the richest quintile of wealth index had the highest PR for all comorbidity groups. These differences remained significant in all models in a stepwise process (online supplementary file 2). In final models, once controlling for sex, age, education, occupation and urbanisation, those in the richest quintile were 2.3 times as likely to have DM and HTN, 4.8 times as likely to have DM and overweight/obesity, 4.9 times as likely to have HTN and overweight/obesity and 4.0 times as likely to have all three comorbidities, than those in the poorest quintile. In these final models, non-manual workers were also significantly more likely than manual workers to have all comorbidity groups. Sex differences were lost on controlling for other factor for all comorbidities groups, except Group C (HTN and overweight/obesity), for which females were 1.4 times as likely to experience both. Older participants were significantly more likely to have group A comorbidity (DM and HTN) DM and Group D (all comorbidities) (table 4).

Table 4.

Modified stepwise Poisson regression models showing prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CI for comorbidities by demographic characteristics among Bangladeshi adults

| Model | Group-A (diabetes and hypertension) |

Group-B (diabetes and overweight/obesity) |

Group-C (hypertension and overweight/obesity) |

Group-D (diabetes, hypertension and overweight/obesity) |

| Model-1 (Wealth index) | ||||

| Wealth index | ||||

| Richest | 3.94 (2.42 to 6.41)* | 9.69 (4.84 to 19.4)* | 6.83 (4.66 to 10)* | 8.67 (3.65 to 20.56)* |

| Richer | 1.52 (0.88 to 2.61) | 3.39 (1.61 to 7.16)* | 3.78 (2.53 to 5.64)* | 2.44 (0.95 to 6.31) |

| Middle | 0.9 (0.47 to 1.71) | 1.63 (0.69 to 3.81) | 1.3 (0.81 to 2.07) | 1.17 (0.37 to 3.7) |

| Poorer | 0.9 (0.47 to 1.73) | 0.81 (0.31 to 2.16) | 1.13 (0.7 to 1.84) | 0.79 (0.24 to 2.64) |

| Poorest | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Model-6 (Wealth index+sex+age+education+occupation+place of residence) | ||||

| Wealth index | ||||

| Richest | 2.32 (1.32 to 4.1)* | 4.84 (2.26 to 10.4)* | 4.85 (3.25 to 7.24)* | 3.99 (1.58 to 10.11)* |

| Richer | 1.12 (0.66 to 1.91) | 2.22 (1.02 to 4.8) | 3.03 (2.04 to 4.49) | 1.59 (0.65 to 3.92) |

| Middle | 0.74 (0.39 to 1.38) | 1.23 (0.54 to 2.82) | 1.1 (0.69 to 1.75) | 0.9 (0.31 to 2.64) |

| Poorer | 0.78 (0.41 to 1.48) | 0.71 (0.27 to 1.88) | 1.06 (0.65 to 1.7) | 0.7 (0.22 to 2.24) |

| Poorest | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 0.67 (0.35 to 1.31) | 0.91 (0.47 to 1.78) | 1.44 (1.06 to 1.96)* | 1.05 (0.46 to 2.36) |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Age | ||||

| Older | 2.17 (1.58 to 2.99)* | 0.87 (0.62 to 1.21) | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.35) | 1.61 (1.05 to 2.49)* |

| Younger | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Education | ||||

| College or higher | 1.38 (0.85 to 2.25) | 1.53 (0.93 to 2.5) | 1.09 (0.82 to 1.45) | 1.4 (0.74 to 2.63) |

| Secondary | 1.06 (0.68 to 1.65) | 1.33 (0.8 to 2.19) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.2) | 1.24 (0.65 to 2.38) |

| Primary | 1.03 (0.69 to 1.53) | 1.42 (0.89 to 2.26) | 1.18 (0.93 to 1.5) | 1.25 (0.69 to 2.28) |

| No education, preschool | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Occupational | ||||

| Non-manual | 3.27 (1.94 to 5.52)* | 4.22 (2.26 to 7.9)* | 3.04 (2.19 to 4.22)* | 3.69 (1.63 to 8.36)* |

| Manual | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 1.33 (0.9 to 1.95) | 1.17 (0.8 to 1.72) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) | 1.72 (0.99 to 3.01) |

| Rural | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

*Statistical significance at p<0.05.

bmjopen-2018-025538supp002.pdf (238.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

This is the first study in Bangladesh that investigated individual and comorbid conditions using a nationally representative sample. We found that within the Bangladesh adult population, aged more than 35 years, the prevalence of DM was 12%, HTN 27% and overweight/obesity 22%. DM, HTN and overweight/obesity were comparatively higher in males than females. More than 14% of the sample also had more than one condition, with 1.3% exhibiting all three. We also found that individual prevalence and comorbidity were higher in those of a higher SES. Once controlling for several confounders, those in the richest quintile of wealth index were significantly more likely than those in the poorest quintile to exhibit comorbidities.

These findings demonstrate an alarming burden of NCDs within Bangladesh, with the rapid growth of overweight in the country becoming a particular public health concern.26–28 As with many other developing countries, Bangladesh is experiencing a nutritional transition and increases in gross domestic product, which have been associated with multiple shifts in food intake and reduced physical activity.29

Although to the authors knowledge, this is the first study on the prevalence of NCDs risk factor comorbidity in Bangladesh using a nationally representative sample, a previous study had found an association between anthropometric indices such as BMI, waist circumference, waist:hip ratio and cardiometabolic risk indicators (FBG, SBP and DBP).30 A further study in four geographical regions, including Bangladesh, reported that every SD higher of BMI was associated with 1.65 and 1.60 times higher probability of DM and 1.42 and 1.28 times higher probability of HTN, for men and women, respectively.31 Other studies have also found that HTN is a common comorbid condition in DM and vice versa,32 while there is considerable evidence for an increased prevalence of HTN in diabetic persons from other populations.33 34

In the current study, overweight/obesity and DM risk were greater among young people which is consistent with a similar study conducted in Indonesia.35 DM, HTN and overweight/obesity were more prevalent in non-manual labour compared with manual labour, which was similar to findings from a study in Barbados.36 However, the present study found males were more likely to suffer comorbidities than females, contradicting findings from previous studies.37 38 We also found that the prevalence of individual conditions (DM, HTN and overweight/obesity) along with the comorbidity of them was higher in urban areas compared with rural, which is consistent with a number of studies conducted in LMICs, including Bangladesh23 32 39–42

Within our study, we found a higher prevalence of individual conditions and comorbidities in higher socioeconomic groups. These findings conflict with trends reported by previous studies conducted in higher income countries.43 44 However, another multicountry study reported that comorbidity was more prevalent among the poor and less educated in low-income countries.45 However, these findings were based on self-reported diagnosis, which may introduce concerns of report and recall bias. Previous research in INDEPTH Asian sites has reported inverse associations between comorbidity and markers of SES.46

The main implications of the present study are the increased burden of NCDs within Bangladesh, along with other LMICs, and the patterning of more than one risk factor within individuals in the population. In contrast to findings from high-income countries, prevalence of individual risk factors and comorbidities was higher in higher SES groups. This points to differences between countries in the population-level determinants of NCDs and highlights that context-specific interventions must be developed to counter them. As a first step, it is important that countries collect and analyse high-quality health data to allow them to develop and target interventions.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of the study were the large nationally representative sample and the collection of blood pressure, blood glucose concentration, body weight and height measurements by health technicians follow standard methods, including biomarker analysis, along with validated measures of SES. The main weakness of the study is the cross-sectional nature, meaning that only associations can be inferred and causality cannot be determined. In addition, although clinical measures of DM, HTN and overweight/obesity were taken, no measurements of blood lipids were taken in the survey, meaning that metabolic syndrome could not be investigated. Waist and hip circumference were also not collected, limiting the analysis that could be performed. Finally, although the study was reported to be representative, only participants 35 years or older had measured anthropometry and biomarkers meaning that the findings reflect this population of adults in the country.

Conclusion

In contrast to more affluent countries, individuals of higher SES in Bangladesh are more likely to exhibit NCDs risk factors and comorbidities than individuals from lower SES status. It is important that we identify the patterning of these conditions within countries if we are to develop effective public health approaches contextualised to the population. This can be done through improved monitoring and surveillance of NCDs, linked to primary care programmes. Such approaches also need policy and system changes, supported by ‘political will’, societal and community support.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank MEASURE DHS for permission to use data from the 2011 Bangladesh DHS. The authors are also grateful to Mehedi Hasan, University of Queensland, Australia.

Footnotes

Contributors: TB, NT, SKD and AAM conceptualised the study. TB, NT, SKD, RDG and AAM designed the study and acquired the data. TB, MSI and MRI conducted the data analysis. TB, NT, MSI, MRI, SKD and AAM interpreted the data. TB, NT and RDG prepared the first draft. TB, NT, SKD and AAM participated in critical revision of the manuscript and contributed to its intellectual improvement. All authors went through the final draft and approved it for submission.

Funding: The authors have not received a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The authors are alone responsible for the integrity and accuracy of data analysis and the writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: BDHS 2011 received ethical approval from ICF Macro Institutional Review Board, Maryland, USA and National Research Ethics Committee of Bangladesh Medical Research Council (BMRC), Dhaka, Bangladesh. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all survey participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset of BDHS 2011 is available at the Demographic and Health Surveys Programme. Extra data is available which is available on request at http://dhsprogram-com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-349.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett D, Bisanzio D, Deribew A, et al. Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1084–150. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31833-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011:161. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abegunde DO, Mathers CD, Adam T, et al. The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007;370:1929–38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61696-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JT, Hamid F, Pati S, et al. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: cross sectional analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127199 10.1371/journal.pone.0127199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015:280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Streatfield PK, Karar ZA. Population challenges for Bangladesh in the coming decades. J Health Popul Nutr 2008;26:261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, ICF International. Bangladesh Urban Health Survey 2013. Dhaka, Bangladesh, Calverton, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahsan KZ, Alam MN, Streatfield PK, et al. Has Bangladesh Entered the Fourth Stage of the Epidemiologic Transition? Proceedings of the International seminar on Mortality: Past, Present and Future, the University of Campinas, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zaman MM, Bhuiyan MR, Karim MN, et al. Clustering of non-communicable diseases risk factors in Bangladeshi adults: An analysis of STEPS survey 2013. BMC Public Health 2015;15:659 10.1186/s12889-015-1938-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, et al. Managing comorbidities in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:95 10.2147/COPD.S54473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roberts KC, Rao DP, Bennett TL, et al. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease multimorbidity and associated determinants in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2015;35:87–94. 10.24095/hpcdp.35.6.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang J, Ma JJ, Liu J, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Comorbidities among Hypertensive Patients in China. Int J Med Sci 2017;14:201–12. 10.7150/ijms.16974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurst C, Thinkhamrop B, Tran HT. The association between hypertension comorbidity and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes patients: a nationwide cross-sectional study in Thailand. Diabetes Metab J 2015;39:395–404. 10.4093/dmj.2015.39.5.395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marak B, Kaur P, Rao SR, et al. Non-communicable disease comorbidities and risk factors among tuberculosis patients, Meghalaya, India. Indian J Tuberc 2016;63:123–5 10.1016/j.ijtb.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pandey AR, Karki KB, Mehata S, et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Comorbid Diabetes and Hypertension in Nepal: Evidence from Non Communicable Disease Risk Factors STEPS Survey Nepal 2013. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2015;13:20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mendenhall E, Norris SA, Shidhaye R, et al. Depression and type 2 diabetes in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:276–85. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Allen L, Williams J, Townsend N, et al. Socioeconomic status and non-communicable disease behavioural risk factors in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e277–e89. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30058-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Varghese C. Reducing premature mortality from non‐communicable diseases, including for people with severe mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2017;16:45–7. 10.1002/wps.20376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011, Preliminary Report. Dhaka, Bangladesh, Calverton, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Biswas T, Islam MS, Linton N. Socio-economic inequality of chronic non-communicable diseases in Bangladesh. PloS One 2016;11:e0167140 10.1371/journal.pone.0167140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Akter S, Rahman MM, Abe SK, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes and their risk factors among Bangladeshi adults: a nationwide survey. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:204–13A. 10.2471/BLT.13.128371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ke-You G, Da-Wei F. The magnitude and trends of under-and over-nutrition in Asian countries. Biomed Environ Sci 2001;14:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rahman M, Williams G, Al Mamun A. Hypertension and diabetes prevalence among adults with moderately increased BMI (23· 0–24· 9 kg/m 2): findings from a nationwide survey in Bangladesh . Public Health Nutr 2017:1–8. 10.1017/S1368980016003566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Biswas T, Uddin MJ, Mamun AA, et al. Increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi women of reproductive age: Findings from 2004 to 2014. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181080 10.1371/journal.pone.0181080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoque ME, Hasan MT, Rahman M, et al. Double burden of underweight and overweight among Bangladeshi adults differs between men and women: evidence from a nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutr 2017;20:2183–91. 10.1186/s13104-015-1377-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biswas T, Garnett SP, Pervin S, et al. The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi adults: Data from a national survey. PloS One 2017;12:e0177395 10.1371/journal.pone.0177395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dietz WH. Double-duty solutions for the double burden of malnutrition. Lancet 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32479-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bhowmik B, Afsana F, Ahmed T, et al. Obesity and associated type 2 diabetes and hypertension in factory workers of Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pradeepa R. The rising burden of diabetes and hypertension in southeast asian and african regions: need for effective strategies for prevention and control in primary health care settings. Int J Hypertens 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sola A, Chinyere O, Stephen A, et al. Hypertension prevalence in an urban and rural area of Nigeria. J Med Sci 2013;4:149–54. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berraho M, El Achhab Y, Benslimane A, et al. Hypertension and type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study in Morocco (EPIDIAM Study). Pan Afr Med J 2012;11 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hashemizadeh H, Sarvelayati D. Hypertension and type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study in hospitalized patients in Quchan, Iran. Iran J Diabetes Obesity 2013;5:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hussain MA, Huxley RR, Al Mamun A, et al. Multimorbidity prevalence and pattern in Indonesian adults: an exploratory study using national survey data. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009810 10.1186/1471-2458-12-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Howitt C, Hambleton IR, Rose AM et al. Social distribution of diabetes, hypertension and related risk factors in Barbados: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008869 10.1186/s41043-017-0101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pearson TA. Education and income: double-edged swords in the epidemiologic transition of cardiovascular disease. Ethn Dis 2003;13:S2–158. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Agborsangaya CB, Lau D, Lahtinen M, et al. Multimorbidity prevalence and patterns across socioeconomic determinants: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2012;12:201 10.1186/1471-2458-12-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rahman M, Williams G, Al Mamun A. Gender differences in hypertension awareness, antihypertensive use and blood pressure control in Bangladeshi adults: findings from a national cross-sectional survey. J Health Popul Nutr 2017;36:23 10.1186/s12872-016-0197-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li G, Hu H, Dong Z, et al. Urban and suburban differences in hypertension trends and self-care: Three population-based cross-sectional studies from 2005-2011. PloS One 2015;10:e0117999 10.1371/journal.pone.0117999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dhungana RR, Pandey AR, Bista B, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of hypertension: a community-based cross-sectional study in municipalities of Kathmandu, Nepal. Int J Hypertens 2016;2016 10.1155/2016/1656938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chowdhury MAB, Uddin MJ, Haque MR, et al. Hypertension among adults in Bangladesh: evidence from a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:22 10.1186/s12872-016-0197-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Connolly V, Unwin N, Sherriff P, et al. Diabetes prevalence and socioeconomic status: a population based study showing increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in deprived areas. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:173–7. 10.1136/jech.54.3.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Glover JD, Hetzel DM, Tennant SK. The socioeconomic gradient and chronic illness and associated risk factors in Australia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy 2004;1:8 10.1186/1743-8462-1-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Mendis S, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: results from the World Health Survey. BMC Public Health 2012;12:474 10.1186/1471-2458-12-474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Van Minh H, Ng N, Juvekar S, et al. Self-reported prevalence of chronic diseases and their relation to selected sociodemographic variables: a study in INDEPTH Asian sites, 2005. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025538supp001.pdf (642.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025538supp002.pdf (238.6KB, pdf)