Abstract

Objective

To evaluate if perceived barriers to accessing mental healthcare (MHC) among individuals with symptoms of depression are associated with their socio-economic position (SEP).

Design

Cross-sectional questionnaire-based population survey from the Lolland-Falster Health Study (LOFUS) 2016–17 of 5076 participants.

Participants

The study included 372 individuals, with positive scores for depression according to the Major Depression Inventory (MDI), participating in LOFUS.

Interventions

A set of five questions on perceived barriers to accessing professional care for mental health problem was posed to individuals with symptoms of depression (MDI score >20).

Outcomes

The association between SEP (as measured by educational attainment, employment status and financial strain) and five different types of barriers to accessing MHC were analysed in separate multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for gender and age.

Results

A total of 314 out of 372 (84%) completed the survey questions and reported experiencing barriers to MHC access. Worry about expenses related to seeking or continuing MHC was a considerable barrier for 30% of the individuals responding and, as such, the greatest problem among the five types of barriers. 22% perceived Stigma as a barrier to accessing MHC, but there was no association between perceived Stigma and SEP. Transportation was not only the barrier of least concern for individuals in general but also the issue with the greatest and most consistent socio-economic disparity (OR 2.99, 95% CI 1.19 to 7.52) for the lowest vs highest educational groups and, likewise, concerning Expenses (OR 2.77, 95% CI 1.34 to 5.76) for the same groups.

Conclusion

Issues associated with Expenses and Transport were more frequently perceived as barriers to accessing MHC for people in low SEP compared with people in high SEP. Stigma showed no association with SEP.

Informed written consent was obtained. Region Zealand’s Ethical Committee on Health Research (SJ-421) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (REG-24–2015) approved the study.

Keywords: mental health, organisation of health services, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study is that it is a population study in a socio-economically-deprived area.

It combines data on present depression scores and socio-economic position (SEP) with proportions of perceived barriers to accessing mental healthcare (MHC) services.

The study was done with patient participation.

A limitation of this study is that the questions used to assess barriers to accessing MHC are not standardised.

There was a potential overlap in the questions between transportation barriers and expense barriers related to seeking or continuing MHC services.

Introduction

Major depressive disorders (MDD) rank third among leading causes of years lived with disability in high-income countries as MDD is common and has an early onset.1 Mental health problems in early age can have a profound impact on educational achievements,2 on income3 and on later unemployment.4 Additionally, a diagnosis of depression is associated with a substantially shorter life expectancy.5

In spite of this, not all people suffering from depression are treated. In a Norwegian survey study, only 12% of respondents with symptoms of depression had ever sought help,6 and a Canadian study found that 40% with symptoms of depression or anxiety perceived an unmet need for care.7 Generally, treatment of patients suffering from depression is insufficient even in high-income countries, as only one in five receives adequate treatment.8

Depressive disorders are closely associated with socio-economic position (SEP). A dose–response relationship has been found between income, as well as education, and incidence, prevalence and persistence of depression.9 Likewise, studies have found that negative socio-economic changes increase the risk of incidence of mental disorders, particularly mood disorders,10 and financial strain in itself is associated with depressive disorder.11 12

Thus, people in low SEP may have a higher need for mental healthcare (MHC) due to increased incidence and prevalence of depression. A recent study found predictors of need for highly-specialised MDD care to be depression severity, younger age at onset, prior poor treatment response, psychiatric comorbidity, somatic comorbidity, childhood trauma, psychosocial impairment, older age and a socio-economically disadvantaged status.13 Although people in low SEP have an increased need for MHC, it is not evident that they use more specialised care. Some studies have found access to specialist care to be based on clinical need with little inequity in SEP,14–16 whereas others report disparity in specialised MHC as psychologists or psychiatrists are not provided equally to persons in low SEP according to need7 17–19 or that higher SEP is associated with more usage of specialised MHC.20 21

The background for initiating the present study was that healthcare statistics (unpublished) in 2013 revealed a significant disparity, as 20% fewer individuals in the most socio-economically deprived municipality in Denmark (Lolland) had been in contact with outpatient MHC (psychologist, private or public psychiatry) than was expected for the population size (unpublished). Several reasons may account for this discrepancy between the expected higher need in a deprived area and the actual use of MHC services, one of them being perceptions of barriers that affect the patients’ choices or preferences, which we aimed to address in this study.

The study objective was to evaluate if perceived barriers to accessing MHC differ across individuals with symptoms of depression according to SEP. We, thereby, expected to gain valuable knowledge for addressing inequality in the use of MHC services.

Method

Study design

The study was conducted as a cross-sectional questionnaire-based population survey.

Setting

The Danish healthcare system is tax-funded and free at delivery for both primary and secondary care; for adults, dental care and psychotherapy are only partly subsidised.22 The general practitioner (GP) fulfils a gatekeeper function, as specialised care is free only after GP referral. Psychotherapy by a psychologist is partly subsidised only for patients referred by a GP for specific conditions: reaction to specific traumatic events, moderate depression and, specifically for citizens between 18 and 38 years, moderate anxiety disorders. In 2014, the out-of-pocket cost to individuals partly subsidised at the time of service was equivalent to 52€ for the first consultation and 44€ for the following sessions.23

Study population and data sources

The Lolland-Falster Health Study (LOFUS) is a publicly funded population survey conducted in the two remote municipalities of Lolland and Guldborgsund, located in a socio-economically deprived area of Denmark that is a 1½−2-hour drive south from the capital Copenhagen. In the 2017 national ranking of all 98 municipalities, these two were ranked the most deprived and the eighth most deprived municipalities.24 Together, the municipalities comprised 103 000 citizens, 50% being 50 years of age or older25 in 2017. The study aims to enrol 25 000 participants of all ages and is conducted from 2016 to 2020. Participants are randomly selected by civil registration number,26 invited by mail and re-invited by phone. The study covers several health areas: mental health, health literacy, social issues, genetics, kidney, ear nose & throat problems and more. Beyond questionnaire responses, LOFUS data contains blood samples and biometrics. The study is described in detail elsewhere.27 The present study relies on responses to the questionnaire from adults, with data drawn from LOFUS at the end of 2017, while data collection was still ongoing.

The subjects included in this study are respondents with symptoms of depression. All respondents who scored >20 on the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) were posed the specific questions on perceived barriers to seeking help for mental health problems, which are described below.

Independent variables

Major Depression Inventory

As part of the LOFUS questionnaire, the respondents filled out the MDI. The MDI is based on the 12-item Likert Scale and has been found to have an adequate internal and external validity for defining different stages of depression.28 The MDI is based on the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depressive disorder,29 with scores ranging from 0 to 50. We used the sum score after excluding the lowest score on question 8 or 9 and, likewise, the lowest score on item 11 or 12, which measured increased/decreased restlessness and increased/decreased appetite, respectively.30 Mild depression is indicated by scores from 21 to 25, moderate depression from 26 to 30 and severe depression by scores from 31 to 50.31 If more than two items were missing in the MDI, the score was categorised as missing.32

Socio-economic position

SEP was measured by employment status, educational attainment and financial strain. Usually income status is included as measure of SEP but information on income was not an item in the questionnaire. Financial strain is not the optimal measurement of SEP; however, it has been found to be associated with depressive and/or anxiety disorder, above the effect of income and to be negatively, but not strongly, correlated with income (r = −0.41, p<0.001).11

Employment status was gathered using 14 different items in the questionnaire. Respondents over the age of 67 were categorised as retired, unless they were employed. The categories of employment were reduced to four in the analyses: Working (employee; self-employed; combined employee and self-employed; military; secondary school pupil; post-secondary student; apprentice; house-wife/husband); Temporary not working (unemployed; rehabilitation; sickness leave 3 months or more); Retired (retired due to age; disability benefit; early retirement); and Other (other).

Educational attainment was measured and classified as follows: No post-secondary education (if the respondent did not complete any post-secondary education); 1–3 years post-secondary education (for vocational or academy/professional graduates of 1–3 years); 3+ post-secondary education (for baccalaureate matriculants who completed 3–4 years); and Academic (for those who completed graduate study of ≥5 years).

The questionnaire gathered responses concerning financial strain with the following question: How often within the last 12 months have you had problems paying your bills? With possible answers: Never; Few months; Approximately half the months in the year; Every month. In the analysis, the categories were reduced to three to gain power, merging Approximately half the months in the year and Every month into one category.

Extrinsic variables

Socio-demographic variables included were gender, age, marital status and cohabitation.

Questions on self-perceived general health (SRH) were provided to respondents with a five-point Likert Scale from Very good to Very bad. In addition, the presence of a Long-standing health problem was posed as a binary question and General activity limitation was gauged in three grades from Severely limited to Not at all. These questions were adopted from the European Health Status Module.33

The questionnaire included inquiries regarding past and present medical problems; specifically related to mental health status, the respondents were asked if they presently suffered or had ever suffered from anxiety disorder and/or depression.

Dependent variables

We developed a short list of questions to be included in the LOFUS questionnaire for respondents who scored positive for symptoms of depression. The questions were inspired by the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation questionnaire by Sara Clement et al.34 Their questionnaire contains 30 items, which was too many to include in the LOFUS study (see online supplementary table 1). The number of questions was reduced and grouped to cover the individual abilities in approaching care as described by Levesque et al35: ability to perceive; ability to seek; ability to reach; ability to pay; and ability to engage (see further description in the online supplementary material, figure 1). A preliminary question on whether considering seeking care had ever been a problem was prompted before the five questions related to the abilities/perceived barriers:

bmjopen-2018-023844supp001.pdf (310.8KB, pdf)

Have any of the reasons listed below prevented, delayed or discouraged you from getting or continuing professional care for a mental health problem?

It has had an impact, that I. .

… have been unsure what to do to get professional care. (termed Knowledge in the following).

… have been concerned for what others might think, say or do. (termed Stigma).

… have had difficulty with transport or travelling for treatment. (termed Transport).

… have not been able to afford the expenses that followed. (termed Expense).

… have had bad experiences with professional care for mental health problems. (termed Experience).

These questions are Not Relevant for me/I do not want to answer.

Answers to question 1–5 were listed in four grades ranging from Not at all to A lot; question six was binary.

In a preliminary form, the questions were evaluated for content validity in a focus-group interview of a group of ten patients and relatives of psychiatric patients (the Panel of Relatives and Patients of Psychiatry Services in Region Zealand) in December 2014. The group found the themes relevant and the questions understandable. They offered some suggestions for rephrasing, which were subsequently followed. The same panel commented on the preliminary results of the study in December 2017.

Statistical analysis

For respondents with symptoms of depression, we estimated the association between SEP and the outcome variables (five types of barriers to MHC: Knowledge; Stigma; Transport; Expense; Experience) in separate multivariable logistic regression models after excluding respondents replying Not relevant. Likewise, we performed the same analyses with the three grades of depression (mild, moderate and severe) and depression score uncategorised (MDI score) as independent variables, which are presented as online supplementary material. The SEP categories were Employment status, Education, and Financial strain. Working, Post-secondary education, and No economic distress were used as reference categories.

The logistic regression models were adjusted for age (18–59 vs 60+) and gender, in addition to the variables studied in the univariate (crude) analysis.

The significance level used was 5% throughout, and all reported CIs were 95%. All statistical analyses were done in Stata 15 (Statacrop, V.1, 2017).

Patient and public involvement

The study objectives were discussed with the members of the Panel of Relatives and Patients of Psychiatry Services in Region Zealand along with the validation of the questions in December 2014. The preliminary results were discussed with the group again in December 2017. The final results were distributed to the group in February 2018 along with an invitation for additional comments. One member of the patient panel responded to the invitation and provided additional comments/discussion. Comments from patients are included in the discussion.

The published article will also be distributed to the patient panel.

Results

Sampling from Lolland-Falster Health Study

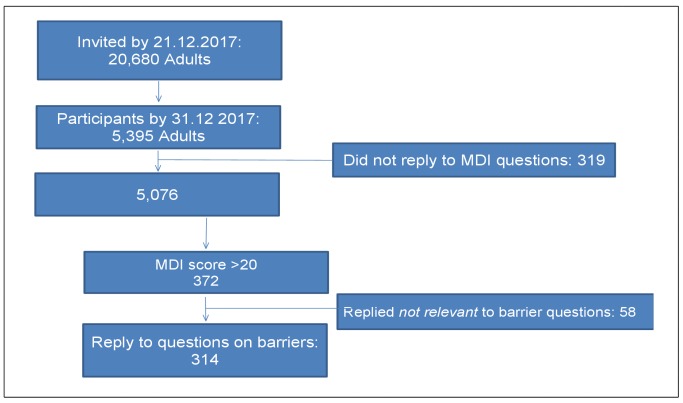

By 21 December 2017, a total of 20 680 adults (age 18+) had been invited to the LOFUS study. By 31 December 2017, a total of 5395 adults had replied to the questionnaire. A total of 319 respondents did not reply on the MDI score element or failed to fill in more than two answers in the test, leaving 5076, of whom 372 (7.3%) reported symptoms of depression and, thus, were prompted the questions on perceived barriers to seeking MHC. Fifty eight replied that the questions were not relevant or would not answer them; thus 314 individuals with a n MDI score >20 were included in the analyses of SEP and perceived barriers (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sampling flowchart. MDI, Major Depressive Inventory.

The total sample consisted of 53% women; 64.5% of the respondents were married, and 80.7% were cohabitating. For the total group, the mean age was 55.7 and the median age was 57.4; for individuals scoring in the depressed range on the MDI, the mean age was 50.2 and the median was 51.4 years.

Compared with the total sample, the respondents reporting symptoms of depression were younger, and more likely to be living alone and unmarried (table 1). They were also more likely to have no post-secondary education, to be temporarily out of work (of whom 33% had symptoms), and to experience more frequent financial strain. Furthermore, their health indicators included: lower self-rated health; more reports of limited physical functioning; more reports of long lasting disease; and former anxiety or depression diagnoses; and more reports to be currently in pharmacological treatment for these disorders.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample and respondents with symptoms of depression (Major Depressive Inventory (MDI) >20)

| Total sample | MDI score >20 | |||||

| Men | Women | Total | % | N | % | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–29 | 198 | 212 | 410 | 8.1 | 55 | 13.4 |

| 30–39 | 180 | 250 | 430 | 8.5 | 41 | 9.5 |

| 40–49 | 357 | 443 | 800 | 15.8 | 82 | 10.3 |

| 50–59 | 519 | 681 | 1200 | 23.6 | 84 | 7.0 |

| 60–69 | 632 | 666 | 1298 | 25.6 | 63 | 4.9 |

| 70–79 | 396 | 371 | 767 | 15.1 | 41 | 5.3 |

| 80+ | 95 | 76 | 171 | 3.4 | 6 | 3.5 |

| Sum | 2377 | 2699 | 5076 | 372 | 7.3 | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1538 | 1708 | 3246 | 64.5 | 181 | 5.6 |

| Partnership | 73 | 108 | 181 | 3.6 | 15 | 8.3 |

| Separated | 12 | 9 | 21 | 0.4 | 5 | 23.8 |

| Divorced | 169 | 195 | 364 | 7.2 | 31 | 8.5 |

| Widower | 59 | 164 | 223 | 4.4 | 11 | 4.9 |

| Not married | 509 | 487 | 996 | 19.8 | 122 | 12.2 |

| Cohabitating | ||||||

| Yes | 1917 | 2141 | 4058 | 80.7 | 248 | 6.1 |

| Secondary schooling | ||||||

| Studying | 20 | 34 | 54 | 1.1 | 5 | 9.3 |

| <8 years | 290 | 203 | 493 | 9.7 | 35 | 7.1 |

| 8–9 years | 610 | 401 | 1011 | 19.9 | 87 | 8.6 |

| 10–11 years | 751 | 913 | 1664 | 32.8 | 112 | 6.7 |

| High school | 522 | 896 | 1418 | 27.9 | 89 | 6.3 |

| Other/foreign | 163 | 215 | 378 | 7.4 | 38 | 10.1 |

| Post-secondary education | ||||||

| No post-secondary | 415 | 529 | 944 | 18.6 | 112 | 11.9 |

| 1–3 years post-secondary | 1307 | 1238 | 2545 | 50.1 | 172 | 6.8 |

| 3+years post-secondary | 495 | 784 | 1279 | 25.2 | 63 | 4.9 |

| Other | 143 | 122 | 265 | 5.2 | 21 | 7.9 |

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Work/study | 1417 | 1526 | 2943 | 58.0 | 167 | 5.7 |

| Temporarily no work | 68 | 121 | 189 | 3.7 | 63 | 33.3 |

| Retired | 843 | 966 | 1809 | 35.6 | 115 | 6.4 |

| Other | 47 | 77 | 124 | 2.4 | 27 | 21.8 |

| Financial strain | ||||||

| Not at all | 2136 | 2404 | 4540 | 89.4 | 275 | 6.1 |

| Few months | 175 | 213 | 388 | 7.6 | 60 | 15.5 |

| Half the months | 23 | 22 | 45 | 0.9 | 13 | 28.9 |

| Every month | 25 | 32 | 57 | 1.1 | 19 | 33.3 |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Very good | 306 | 328 | 634 | 12.5 | 7 | 1.1 |

| Good | 1348 | 1524 | 2872 | 56.6 | 83 | 2.9 |

| Fair | 616 | 697 | 1313 | 25.9 | 181 | 13.8 |

| Bad | 89 | 137 | 226 | 4.5 | 90 | 39.8 |

| Very bad | 12 | 6 | 18 | 0.4 | 9 | 50.0 |

| General activity limitation | ||||||

| Not limited at all | 1561 | 1630 | 3191 | 63.2 | 114 | 3.6 |

| Limited but not severely | 672 | 906 | 1578 | 31.3 | 166 | 10.5 |

| Severely limited | 132 | 146 | 278 | 5.5 | 88 | 31.7 |

| Long-standing illness. Yes | 1052 | 1200 | 2252 | 44.7 | 244 | 10.8 |

| Anxiety, now or earlier. Yes | 110 | 223 | 333 | 6.6 | 111 | 33.3 |

| Depression, now or earlier. Yes | 145 | 230 | 375 | 7.4 | 138 | 36.8 |

| Medication anxiety. Yes | 71 | 119 | 190 | 3.8 | 65 | 34.2 |

| Medication antidepressants. Yes | 85 | 173 | 258 | 5.1 | 66 | 25.6 |

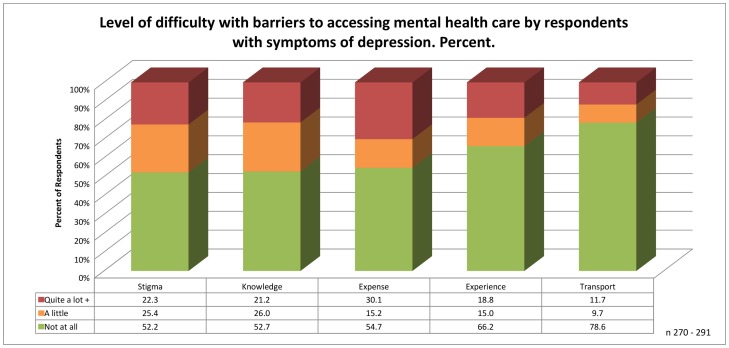

Of those responding to the questions, more than half perceived no problems at all in accessing professional care, least of all Transport.

Among those who did have concerns about accessing or continuing professional MHC, Expense was the most common problem, as 30.1% indicated expenses had prevented, deterred or delayed them either Quite a lot or A lot (both responses aggregated in the ‘Quite a lot + category in figure 2). Likewise, the second most common concern was related to Stigma, phrased in the questionnaire as ‘what others might think, say or do’, which was a serious concern for 22.3%; approximately the same proportion (21.2%) had concerns related to Knowledge, or how to find help for MHC. Transport was not a problem for 78.6%, with only 11.7% reporting that it negatively affected access.

Figure 2.

Responses on perceived barriers to accessing mental health care (MHC), proportions.

Perceived barriers to accessing healthcare by SEP are shown in table 2 (crude numbers are shown in online supplementary table 2). Perceptions of Stigma did not show any significant difference across the socio-economic groups, however measured. Lack of Knowledge was a significant problem for respondents without Post-secondary education compared with those who had completed some Post-secondary education (adjusted OR 2.26 95% CI 1.1 to 4.6) and for respondents with occasional (Few months), but not regular, Financial strain when compared with those with no Financial strain. Low SEP, as measured by educational level and Financial strain, was associated with perceived barriers concerning Transport and Expense; whereas low SEP measured by employment status alone was associated with concerns related to Transport. The retired respondents were more likely to perceive bad Experience with MHC services as a barrier to seeking or continuing MHC compared with respondents who were working. Transport showed the greatest disparity across the socio-economic groups.

Table 2.

Adjusted OR for perceived barriers for accessing mental health care (MHC) by three indicators of Socio-economic position (SEP)

| Employment status | Education | Financial strain | |||||||||

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | n | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | n | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | n | |||

| Stigma | |||||||||||

| Working | 1 | 291 | 3+ years | 1 | 290 | Not at all | 289 | ||||

| Temporarily not working | 0.9201 | 0.4880 to 1.735 | 1–3 years | 1.087 | 0.5740 to 2.058 | Few months | 0.8994 | 0.4841 to 1.671 | |||

| Retired | 0.6808 | 0.3420 to 1.356 | No post-secondary | 1.166 | 0.5833 to 2.332 | Half the time+ | 1.749 | 0.6933 to 4.410 | |||

| Other | 0.3815 | 0.1431 to 1.017 | Other | 0.6699 | 0.1969 to 2.279 | ||||||

| Knowledge | |||||||||||

| Working | 1 | 292 | 3+ years | 1 | 291 | Not at all | 1 | 290 | |||

| Temporarily not working | 1.204 | 0.6390 to 2.268 | 1–3 years | 1.597 | 0.8309 to 3.070 | Few months | 2.515 | 1.335 to 4.739 | |||

| Retired | 0.5003 | 0.2480 to 1.009 | No post-secondary | 2.263 | 1.115 to 4.592 | Half the time+ | 2.372 | 0.9404 to 5.985 | |||

| Other | 0.5004 | 0.1884 to 1.329 | Other | 4.752 | 1.297 to 17.412 | ||||||

| Expense | |||||||||||

| Working | 1 | 289 | 3+ years | 1 | 288 | Not at all | 289 | ||||

| Temporarily not working | 1.700 | 0.8911 to 3.323 | 1–3 years | 1.835 | 0.9324 to 3.612 | Few months | 4.268 | 2.172 to 8.385 | |||

| Retired | 1.537 | 0.7451 to 3.171 | No post-secondary | 2.773 | 1.336 to 5.757 | Half the time+ | 9.623 | 2.708 to 34.194 | |||

| Other | 0.7456 | 0.2822 to 1.970 | Other | 2.031 | 0.5762 to 7.156 | ||||||

| Experience | |||||||||||

| Working | 1 | 287 | 3+ years | 1 | 286 | Not at all | 1 | 286 | |||

| Temporarily not working | 0.9581 | 0.4820 to 1.905 | 1–3 years | 1.043 | 0.5392 to 2.019 | Few months | 1.152 | 0.5999 to 2.212 | |||

| Retired | 2.143 | 1.024 to 4.485 | No post-secondary | 0.6435 | 0.3073 to 1.347 | Half the time+ | 2.385 | 0.9685 to 5.874 | |||

| Other | 1.531 | 0.5932 to 3.952 | Other | 0.7503 | 0.2024 to 2.781 | ||||||

| Transport | |||||||||||

| Working | 1 | 290 | 3+ years | 1 | 289 | Not at all | 288 | ||||

| Temporarily not working | 3.184 | 1.463 to 6.931 | 1–3 years | 1.603 | 0.6502 to 3.954 | Few months | 1.746 | 0.8392 to 3.634 | |||

| Retired | 4.442 | 1.900 to 10.384 | No post-secondary | 2.988 | 1.187 to 7.518 | Half the time+ | 9.889 | 3.745 to 26.113 | |||

| Other | 2.169 | 0.6948 to 6.773 | Other | 1.019 | 0.1835 to 5.659 | ||||||

Adjusted for: gender; age ±60; 95% CI, significant results are marked in bold.

SEP showed no association with any of the barriers or with years of schooling (not shown). Using depression as an independent variable, we found that severity of depression (both, measured as a categorical variable and a score) was associated with perceived barriers in relation to Expense and Transport, but not associated with any other perceived barriers (see online supplementary material table 3).

Discussion

Principal findings

In this study of perceived barriers to accessing MHC by respondents with present symptoms of depression, we found that almost 1/3 of the respondents indicated that Expense related to accessing MHC was a considerable barrier; this perception was more prevalent among individuals without Post-secondary education and individuals experiencing Financial strain. Transport presented the least prevalent barrier in general; but on the other hand, transportation also presented the greatest and most consistent socio-economic disparity across all measurements of SEP. Transport and Expenses associated with accessing MHC were a problem for disadvantaged individuals.

Stigma was an issue of concern for 22% of the respondents but did not vary significantly according to SEP, whereas Lack of knowledge about how to get help was a significantly greater problem for individuals without Post-secondary education as compared with individuals with Post-secondary education.

Lack of knowledge about how get to help and bad experience were perceived as a problem for 1/5 of the individuals overall as well.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A strength of this study was its use of information from a population study from a deprived area in combination with data on present depression score, information on SEP and perceived barriers to accessing MHC; by this design we were able determine the significance of different barriers to access for potential MHC patients in a deprived area. We are not aware of similar studies.

A limitation in our study was that the items used as dependable variables were not fully validated; validation would be preferred in order to compare to other studies. The Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation - version 3 (BACE-3), at 30 questions, was too extensive to use in the LOFUS study, which already consisted of close to 100 questions; this was also the reasoning behind our focus on five central concepts of barriers to access. The external validity of the questions is supported by the use of generally accepted and validated concepts of abilities and as such is comparable to other studies. The content validity was tested by the panel of patients and patients’ relatives and the questions found to be sound, but in retrospect, might not measure the concept of self-efficacy very well. We used the answer Not relevant/Do not want to reply as an indicator that the individual preferred to handle problems without help. It would have been prudent, however, to ask a more direct question about perceptions of need for care; it is possible that some individuals did not find the question relevant because while they experienced mental health issues, they did not perceive a need for further care. We found no correlation between the answer to the question of relevance and SEP, except for retired respondents, who tended to state Not relevant less frequently, compared with respondents Working (not shown).

Another limitation was that the question about transport was not clearly separated from the question about perceived barriers in relation to Expenses, as it was not specified whether Expenses included transportation-related expenses. Thus, we have no clear determination whether Transport as a barrier is primarily a logistical or an economical barrier, or some combination thereof.

Comparison with other studies

The total sample contained more respondents in the age group 50–69 and fewer in the younger and older age groups compared with the study population; additionally, as compared with the background population, the LOFUS sample is over represented by individuals with +3 years post-secondary education vs No post-secondary education by almost 3:1 according to the general population statistics drawn from Statistics Denmark.25 For the total sample, questions on SRH were rated higher in the sample than the national levels36 even though long-lasting illness was more prevalent in the sample (44.7% compared with a national rate of 35.6%)36; the rate of respondents with severely limited physical functioning was close to the national proportions.37 The group with symptoms of depression had scores well below the national levels in all health-related variables. The total sample may over-represent the middle-aged to older part of the population, an issue seen in national surveys too.38

7.3% had symptoms of depression when the summed MDI score was used, which is a considerably higher rate than found by any other survey in Denmark; however, a recent national survey reported that 7.0% adults suffer from depressed mood, including 7.8% in the region of Zealand.36 Eurostat reported a prevalence of 6.3% adults with depressive symptoms and 3% with major depression symptoms in Denmark.39 In the present study, 225 respondents reported both a core symptom of depression Most of the time or more and a summed MDI score >20, equivalent to an MDD prevalence of 4.4%. A comparable study by Ellervik et al found 2.5% with a summed MDI score >25; we found 3.8%.40 The present data is a sub-sample from a population survey in a deprived area, which could explain the high rate of depression symptoms found.

We found perceived Stigma to be of Quite a lot or A lot of concern for 20% of the respondents. This corresponds with findings in a systematic review, where overall 20%–25% respondents in 44 studies reported Stigma as a barrier to accessing MHC services.41 Stigma showed no association to SEP in our data. We have not been able to verify this in other studies except for one Canadian study, which likewise found no association between years of education and experiencing Stigma in MHC. However, they did find perceived Stigma more prevalent among respondents not working.42 In the Panel of Relatives and Patients of Psychiatry Services of Region Zealand, it was said that patients with mental disorders, and their relatives, pull the curtains together when they meet with each other privately, and that patients are indeed concerned with what others might think.

One in five respondents experienced Knowledge as a barrier and had doubts about what to do to get professional help. With free access to a GP in Denmark, and the GP universally understood to be the gatekeeper for referrals, this is puzzling. Among respondents with symptoms of depression, 138 reported former or present depression, and 35 of them (25%) still answered that they experienced Knowledge to be a barrier Quite a lot or A lot of the time. Of those with symptoms of depression and presently taking antidepressant medication, 8 (12%) had doubts about what to do to get help. This could be due to the nature of the disease, but we did not find support for this, as we found no association to Knowledge with the severity of symptoms of depression. However, a Canadian study on perceived unmet need by respondents with symptoms of anxiety or depression found high symptom scores were associated with a higher degree of unmet need,7 and not knowing how or where to get help was the most reported reason. The Panel of Relatives and Patients of Psychiatry Services of Region Zealand was not very surprised by this finding: despite free access to a GP, one individual reported that he could not get a family GP, but had to meet changing doctors in a regional clinic (due to lack of GPs in the area). Another mentioned that the waiting time for an appointment with a GP could be weeks (due to lack of GPs).

It could be argued that older people may be more reluctant to use MHC and feel more stigmatised by the need for psychotherapy.43 44 We did not find support for this as the Retired group did not differ in perception of Stigma from employed persons. Likewise, older retired persons might be less willing to pay for the expenses associated with treatment, but we did not find support for this either, as Expense was not a significant barrier for the Retired group compared with the Working group.

Use of MHC is sensitive to cost,45 and especially so for persons in low SEP.46 This corresponds with our findings that Expenses associated with MHC were considered a common barrier for seeking help and the concern of almost 1/3 of our respondents, and by two to five-fold more by respondents without Post-secondary education or in Financial strain. This knowledge is important when research has shown that Financial strain is strongly associated with higher odds for depression11 and for prescription of anti-depressants.47 A German study found that even with free access to a psychologist, these services are used less by people in low SEP,19 which could be explained in part by our findings; people without Post-secondary education may have less knowledge of how to access professional MHC, thus leading to lower usage of available services.

Experience with earlier MHC treatment made retired respondents more reluctant to seek MHC as compared with the working population. This may not necessarily be due to bad experiences with healthcare professionals, though stigmatisation can be a problem in health services too48; reports of past experience as a barrier could also indicate bad experience with side-effects from a medication. Our study was not designed to capture or explore this nuance. Retired individuals are more likely to have more experience with healthcare, and this group includes people receiving early retirement pensions, which could indicate a chronic illness leading to early retirement and thus more opportunities for more bad experiences. The patient panel questioned the respondents’ experience with MHC, since the rates of bad past experiences were so low, with one remarking: ‘Those who are really feeling bad have not participated in this survey’. For the panel, bad experience was a common deterrent to MHC, which may indicate an important area of future study.

Transport was perceived to be a greater problem by persons in low SEP compared with individuals in high SEP. This aligns well with our previous findings of the impact of distance and SEP on MHC use by patients in antidepressant treatment.21 However, the question was not well distinguished from the question on expenses. Difficulty with transport or travelling includes the time spent to reach services and coordinate with other obligations – taking care of family duties or take time off at work etc. Reliance on infrequent or inadequate public transportation could also be a reason for answering positively to this question, but the study was not designed to capture information regarding public vs private transportation; for example, the patient panel was surprised that transport was a minor issue for the respondents, since it was viewed by them to be both time-consuming and expensive.

Meaning of the study and possible explanations and implication for policy-makers

The study aimed to evaluate if perceived barriers to accessing MHC differ across individuals with symptoms of depression according to their SEP. The answer in this study is quite clear: lack of Post-secondary education was linked to greater perceived barriers to MHC and expenses are considered a barrier to MHC for those with No post-secondary education and in Financial strain. Low mental health literacy, defined as knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid in their recognition, management and prevention,49 could be a part of the explanation, since low mental health literacy is also associated with low SEP.50 Thus, empowering the community to take action for better mental health literacy51 can lead to increased help-seeking by individuals in low SEP. In Denmark, two programmes on improving mental health literacy exist: Mental Health First Aid52 and the ABC mental health initiative,53 both adopted from Australia. An approach directed more specifically toward deprived areas within such programmes might improve SEP equity in MHC treatment.

Addressing barriers and easing access for the deprived is obviously necessary. Lack of Post-secondary education is associated with greater perception of barriers to MHC, in addition to an increased prevalence of mood disorders. Clearly, our results showed that Expense is a barrier for people in low SEP, but as found in the German study,19 people in low SEP use psychologists less frequently even with free access. Psychotherapy is associated with the ability to engage, which in itself could be more difficult if an individual struggles with social and economic problems on top of mental ones. In order to address these related barriers, the deprived and depressed probably have additional needs beyond medication and psychotherapy, such as social supports and social/domestic/workplace intervention.

In a future study it could be interesting to investigate the association between depression score, perceived barriers and use of MHC for a period after the score. Future research could also investigate which experiences cause retired respondents with symptoms of depression to hesitate to access MHC. Further improvements and validation of a short-form questionnaire as the present could be beneficial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

With acknowledgement to the Panel of Relatives and Patients of Psychiatry Services of Region Zealand for contributing to validate the questions on perceived barriers and commenting on the outcomes, with special gratitude to Anja Bang. We thank LOFUS for providing the data and Randi Jepsen for kind support. We also thank the Health Research Foundation of Region Zealand for financial support and particularly former head nurse Tove Kjærbo for initiating the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AP conceived the research and developed and validated the questions on barriers supervised by AH. AP wrote the first draft of the manuscript assisted by LHH. AH, ES and FBW contributed to the data analysis, interpretation of results and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The study has been supported by an unrestricted grant (No 15-000342) from the Health Research Foundation of Region Zealand.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study, along with the Lolland-Falster Health Study, was approved by Region Zealand’s Ethical Committee on Health Research (SJ-421) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (REG- 24 – 2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elovainio M, Pulkki-Råback L, Jokela M, et al. Socioeconomic status and the development of depressive symptoms from childhood to adulthood: a longitudinal analysis across 27 years of follow-up in the Young Finns study. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:923–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asselmann E, Wittchen HU, Lieb R, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical, and functional long-term outcomes in adolescents and young adults with mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018;137:6–17. 10.1111/acps.12792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thielen K, Nygaard E, Andersen I, et al. Employment consequences of depressive symptoms and work demands individually and combined. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:34–9. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord 2016;193:203–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roness A, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Help-seeking behaviour in patients with anxiety disorder and depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:51–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dezetter A, Duhoux A, Menear M, et al. Reasons and determinants for perceiving unmet needs for mental health in primary care in Quebec. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:284–93. 10.1177/070674371506000607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:119–24. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.188078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:98–112. 10.1093/aje/kwf182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barbaglia MG, ten Have M, Dorsselaer S, et al. Negative socioeconomic changes and mental disorders: a longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:55–62. 10.1136/jech-2014-204184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dijkstra-Kersten SM, Biesheuvel-Leliefeld KE, van der Wouden JC, et al. Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:660–5. 10.1136/jech-2014-205088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahnquist J, Wamala SP. Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. the Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health 2011;11:788 10.1186/1471-2458-11-788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Krugten FC, Kaddouri M, Goorden M, et al. Indicators of patients with major depressive disorder in need of highly specialized care: A systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171659 10.1371/journal.pone.0171659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glozier N, Davenport T, Hickie IB. Identification and management of depression in Australian primary care and access to specialist mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:1247–51. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dey M, Jorm AF. Social determinants of mental health service utilization in Switzerland. Int J Public Health 2017;62:85–93. 10.1007/s00038-016-0898-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boerema AM, Ten Have M, Kleiboer A, et al. Demographic and need factors of early, delayed and no mental health care use in major depression: a prospective study. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:367 10.1186/s12888-017-1531-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vasiliadis HM, Tempier R, Lesage A, et al. General practice and mental health care: determinants of outpatient service use. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:468–76. 10.1177/070674370905400708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hansen AH, Høye A. Gender differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient specialist services in Tromsø, Norway are dependent on age: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:477 10.1186/s12913-015-1146-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Epping J, Muschik D, Geyer S. Social inequalities in the utilization of outpatient psychotherapy: analyses of registry data from German statutory health insurance. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:147–644. 10.1186/s12939-017-0644-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evans-Lacko S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med 2018;48:1–12. 10.1017/S0033291717003336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Packness A, Waldorff FB, Christensen RD, et al. Impact of socioeconomic position and distance on mental health care utilization: a nationwide Danish follow-up study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:1405–13. 10.1007/s00127-017-1437-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pedersen KM, Andersen JS, Søndergaard J. General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25(Suppl 1):S34–8. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Larsen A. Psykologbehandling [Treatment by psychologist]. 2014. www.sundhed.dk/borger/sygdomme-a-aa/sociale-ydelser/sociale-ydelser/behandling/psykologbehandling/

- 24. Ministry of Economics- and Interior. Key figures of municipalities [Public Database]: www.noegletal.dk, 2018.

- 25. Statistics Denmark. StatBank Denmark [Public Database]: www.statistikbanken.dk, 2015.

- 26. Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jepsen R, Egholm CL, Brodersen J, et al. Lolland-Falster Health Study: study protocol for a household-based prospective cohort study. Scand J Public Health 2018:140349481879961 10.1177/1403494818799613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, et al. The internal and external validity of the Major Depression Inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med 2003;33:351–6. 10.1017/S0033291702006724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization; The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bech P, Rasmussen NA, Olsen LR, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the Major Depression Inventory, using the Present State Examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord 2001;66(2-3):159–64. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00309-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bech P, Timmerby N, Martiny K, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) as depression severity scale using the LEAD (Longitudinal Expert Assessment of All Data) as index of validity. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:190 10.1186/s12888-015-0529-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bech P. Clinical Psychometrics. 1st edn Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012:153–53. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eurostat. European Health Interview Survey (EHIS wave 2). Methodological manual. Methodologies and Working papers. Luxembourg: European Union, 2013:1–202. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clement S, Brohan E, Jeffery D, et al. Development and psychometric properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:36 10.1186/1471-244X-12-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:18 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jensen HD, Ekholm M, Christensen AI. Health of the Danes - The National Health Profile. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen NBoH, 2018:1–134. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnsen NFD, Michelsen S, Juel K. Health profile of adults with impaired or reduced physical functioning. København: Syddansk Universitet, 2014:1–134. [Google Scholar]

- 38. National Board of Health. Mental Healt of Adult Danes. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39. European Union. 2018. Eurostat. European Commission:Luxenburg.

- 40. Ellervik C, Kvetny J, Christensen KS, et al. Prevalence of depression, quality of life and antidepressant treatment in the Danish General Suburban Population Study. Nord J Psychiatry 2014;68:507–12. 10.3109/08039488.2013.877074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med 2015;45:11–27. 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, et al. Perceived Stigma among Recipients of Mental Health Care in the General Canadian Population. Can J Psychiatry 2016;61:480–8. 10.1177/0706743716639928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, et al. Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;18:531–43. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. ten Have M, de Graaf R, Ormel J, et al. Are attitudes towards mental health help-seeking associated with service use? Results from the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:153–63. 10.1007/s00127-009-0050-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sevilla-Dedieu C, Kovess-Masfety V, Gilbert F, et al. Mental health care and out-of-pocket expenditures in Europe: results from the ESEMeD project. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2011;14:95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kiil A, Houlberg K. How does copayment for health care services affect demand, health and redistribution? A systematic review of the empirical evidence from 1990 to 2011. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:813–28. 10.1007/s10198-013-0526-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ahnquist J, Wamala SP. Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. The Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health 2011;11:788 10.1186/1471-2458-11-788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mood Disorders Society of Canada. 2007. Stigma and discrimination - as expressed by mental health professionals.

- 49. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust 1997;166:182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dunn KI, Goldney RD, Grande ED, et al. Quantification and examination of depression-related mental health literacy. J Eval Clin Pract 2009;15:650–3. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol 2012;67:231–43. 10.1037/a0025957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jensen KB, Morthorst BR, Vendsborg PB, et al. Effectiveness of mental health first aid training in Denmark: a randomized trial in waitlist design. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2016;51:597–606. 10.1007/s00127-016-1176-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Koushede V. Act-Belong-Comit: National Institute of Public Health. 2018. http://www.si-folkesundhed.dk/Forskning/Befolkningens%20sundhedstilstand/Mental%20sundhed/ABC%20for%20mental%20sundhed.aspx?lang=en

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Ministry of Economics- and Interior. Key figures of municipalities [Public Database]: www.noegletal.dk, 2018.

- European Union. 2018. Eurostat. European Commission:Luxenburg.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023844supp001.pdf (310.8KB, pdf)