Abstract

Objective

Morphine is frequently used in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) due to its analgesic effect, it being recommended in the main cardiology guidelines in Europe and the USA. However, controversy exists regarding its routine use due to potential safety concerns. We conducted a systematic review of randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies to synthesise the available evidence.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and trial registries.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

We included RCTs and observational studies evaluating the impact of morphine in cardiovascular outcomes or platelet reactivity measures.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were screened, extracted and appraised by two independent reviewers. The data were pooled results using a random-effects model. Outcomes included in-hospital mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), platelet reactivity (using VerifyNow) and bleeding, reported as relative risk (RR) with 95% CI. We assessed the confidence in the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework. We followed the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Results

Five RCTs and 12 observational studies were included, enrolling 69 993 participants. Pooled results showed an increased risk of in-hospital mortality (RR 1.45 [95% CI 1.10 to 1.91], low GRADE confidence), MACE (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.45) and an increased platelet reactivity at 1 and 2 hours (59.37 platelet reactivity units [PRU], 95% CI 36.04 to 82.71; 68.28 PRU, 95% CI 37.01 to 99.55, high GRADE confidence) associated with morphine. We found no significant difference in the risk of bleeding. We found no differences in subgroup analyses based on study design and ACS subtype.

Conclusions

Morphine was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and MACE but the high risk of bias leads to low result confidence. There is high confidence that morphine decreases the antiplatelet effect of P2Y12 inhibitors.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016036357.

Keywords: morphine, acute coronary syndrome, platelet reactivity, meta-analysis, systematic review, stemi

Strengths and limitations.

We assessed data from both randomised trials and observational studies.

The risk of bias across most observational studies is high, which raises concerns in pooling data with the far smaller randomised trials.

To reduce the impact of the potential bias, before meta-analysis we adjusted the within-study variance–covariance matrix of observational studies at a critical risk of bias using a precision correction, a weight factor that provides more conservative pooled estimates.

Key data were not adequately reported across many of the included studies.

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to appraise the available evidence.

Introduction

Worldwide, cardiovascular events are the leading cause of death.1 The burden of disease will likely remain high2 3 as the incidence of cardiovascular events is expected to continue increasing.4

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors), anticoagulants and coronary revascularisation are the mainstay in the early treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and their use likely improves prognosis.5–7 In both Europe and the USA, morphine, a potent analgesic that is a competitive agonist of μ-receptors in the central nervous system and smooth muscle, is recommended for pain control in the ACS setting.7 However, the activation of opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus decreases gut motility and secretion, inhibiting the activation of P2Y12 inhibitors by decreasing their absorption and bioavailability.8 There is conflict regarding the possibility that morphine interferes with P2Y12 inhibitors in the achievement of an adequate antithrombotic milieu,7 9 10 which may decrease the efficaciousness of antiplatelet drugs, if these are given concurrently with morphine. We conducted a systematic review of randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies to evaluate the safety of morphine use in ACS, hypothesising that we would find a clinically meaningful result.

Methods

This systematic review followed the reporting principles of Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.11 12Patients and public were not involved in this review.

Eligibility criteria

We considered longitudinal studies (ie, RCTs and observational studies) evaluating the impact of morphine in cardiovascular outcomes or platelet reactivity measures. The target population was patients with ACS, which can be either ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST elevated acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS).13 Studies had to evaluate morphine (irrespective of the administration route or dose) against placebo, control (no intervention arm) or any other analgesic non-opioid drug.

Primary outcomes were in-hospital mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), as defined by the PLATO trial (cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal MI or non-fatal stroke).14 Secondary outcomes comprised additional safety outcomes, as defined within the included studies (as reported in the original studies, including morphine-related adverse events such as bleeding, nausea/emesis, bradycardia, hypotension and respiratory insufficiency) and platelet reactivity (a pharmacodynamic outcome, sought through the VerifyNow method, which is the most widely used assay to evaluate platelet reactivity and shows a stronger correlation with MACE in ACS than other methods, namely multiple electrode aggregometry (MEA)/Multiplate10 15). VerifyNow is a blood test that measures platelet reactivity by the rate and extent of light changes in whole blood as platelets aggregate, and therefore measures platelet response to major antiplatelet agents.16

Information sources and search method

Potentially eligible studies were identified through an electronic search of CENTRAL (Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and clinicaltrials.gov from inception to November 2018 (online supplementary material). No language restrictions were applied. We cross-checked reference lists of reports for potential additional studies.

bmjopen-2018-025232supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Study selection and data collection process

Two reviewers (GSD and either FBR or ANF) independently screened the titles and abstracts yielded by the search and assessed the full texts of the selected studies to determine the appropriateness for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer (DC) serving as final arbitrator. The reasons for exclusion were recorded at the full-text screening stage.

Two reviewers (ANF and GSD) extracted study data following a pre-established data collection form. Data from studies’ plots were retrieved through Plot Digitizer V.2.6.8. When studies presented different estimates of the outcome of interest, we extracted the most precise or adjusted measures.

Risk of bias was independently evaluated by two authors (GSD and ANF) using different tools according to study design. For RCTs, we used the Cochrane risk of bias tool, where domains were qualitatively classified as at high, unclear or low risk of bias.17 The overall risk of bias for each RCT was divided as high or low risk, with high risk being those RCTs in which at least one domain was assessed at a high risk of bias, or more than three domains were had a rating of unclear. For observational studies we used the ROBINS-I tool, assessing the following domains: confounding, selection of participants, classification of intervention, deviations from intervention, missing data, measurement of outcome and selection of reported results.18 These domains were qualitatively classified as at critical, serious, moderate or low risk of bias. The overall risk of bias for each observational study was divided as critical or non-critical, following ROBINS-I criteria. Risk of bias graphs was derived from these tools.

Statistical analysis

We used OpenMetaAnalyst19 and Review Manager20 for statistical analysis and to derive forest plots. We used a random-effects model to pool data owing to the anticipated heterogeneity in the included trials, in particular differences in study design. We reported pooled dichotomous data using risk ratios (RRs) and continuous data the mean difference (MD), reporting 95% CIs and corresponding p values for both. Heterogeneity was assessed using I.2 21 We present effect estimates as RR because relative estimates are more similar across studies with different designs, populations and lengths of follow-up than absolute effects.22 When raw data or RR was unavailable, we used the HR or OR provided the estimate was small.23 24 Preplanned subgroup analyses considering study design (RCTs and observational studies) and ACS type were conducted. A sensitivity analysis was also performed, in which RCTs at high risk of bias and observational studies at critical risk of bias were excluded from the analysis. Reporting bias was performed through funnel plot examination and statistical methods providing that a sufficient number of studies were included.25

When observational studies were assessed as having a critical risk of bias, we adjusted the within-study variance–covariance matrix using a precision correction of 0.1 that will provide more conservative pooled estimates.26 27 This conservative weight factor was based on expert-based clinical grounds.

We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment and Evaluation (GRADE) framework to report the overall quality of evidence. The certainty in the evidence for each outcome was graded as high, moderate, low or very low.28

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this review.

Results

Included studies

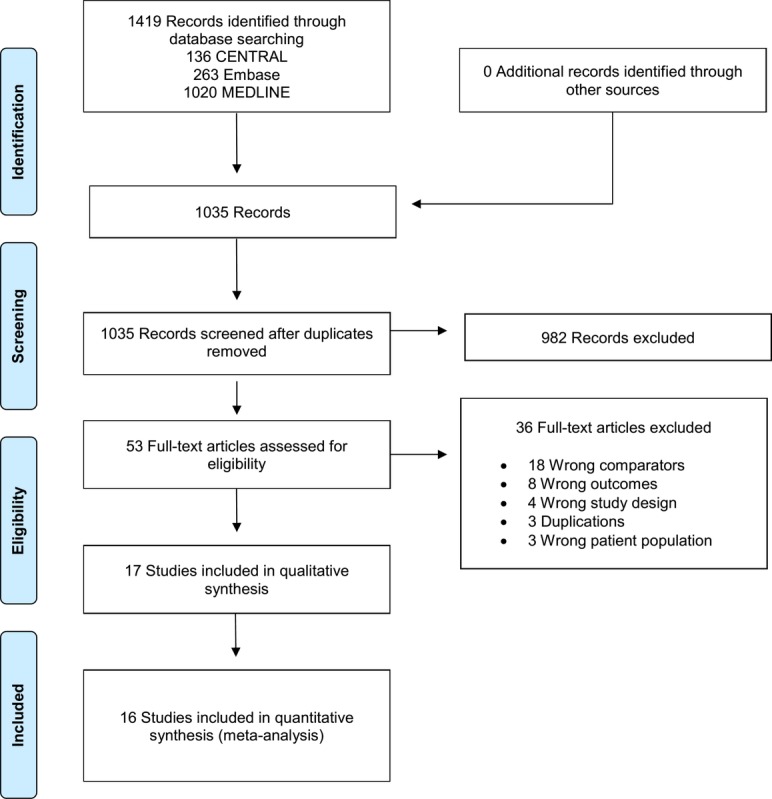

The search returned 1419 records, resulting in 1035 records after removing all duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 53 articles were assessed for full-text screening, with 17 being included for qualitative and quantitative syntheses, 5 being RCTs29–33 and 12 being observational studies.10 34–44 We did not retrieve any unpublished study (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

The characteristics of the included studies can be seen in table 1 and table 2. Study publication dates ranged from 1969 to 2018, with sample sizes between 12 and 57 039 participants. The largest study, Meine et al,34 a retrospective cohort study, accounted for 81% of the participants in this review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the randomised controlled trials

| Study | Location | Mean follow-up | Patients | Antiplatelet medication used | Morphine characteristics | Comparator | N (total) | Mean age | Primary outcome |

| Bressan et al31 | Single centre, Italy | 24 hours | Patients with AMI, chest pain and symptoms<6 hour | None | 10 mg IM single dose | Indoprofen | 40 | 54 | Assessment of analgesic effect of indoprofen in AMI patients |

| Everts et al29

(MEMO Study) |

Single centre, Sweden | 6 months | Patients admitted to the coronary care unit because of symptoms of suspected AMI | None | 2–7.5 mg IV, single to multiple doses | Metoprolol | 265 | 66.6 | Assessment of analgesic effect of metoprolol in suspected or definitive AMI patients |

| Kubica et al30

(IMPRESSION Study) |

Single centre, Poland | Hospital stay | Patient with the diagnosis of STEMI or NSTEMI | Aspirin and ticagrelor | 5 mg IV single dose | Placebo | 70 | 61.6 | Assess the influence of morphine on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ticagrelor and its active metabolite |

| Lapostolle et al32 (ATLANTIC–Morphine) | Multicentre | 30 days | STEMI | Aspirin and ticagrelor | NR | Placebo | 1862 | 60.8 | TIMI Flow Grade 3 of culprit vessel at initial angiography and ST-segment elevation resolution Pre-PCI≥70% (coprimary outcomes) |

| Thomas et al33 | Single centre, UK | 24 hours | STEMI | Aspirin and prasugrel | 5 mg IV single dose | Placebo | 12 | 64 | VerifyNow platelet reactivity |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NR, not reported; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the non-randomised studies

| Study | Location, study design | Follow-up (years) | Patients | Antiplatelet medication used | Morphine characteristics | Comparator | N | Mean age (SD) | Outcome measures | Ascertainment | Outcome adjustments for confounders | |

| Drug use | Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Bellandi et al36 | Italy, Greece, prospective | 2 | STEMI patients undergoing PPCI and receiving either prasugrel or ticagrelor | NR | 6±3 mg, no additional information | No intervention | 182 | 64 (13) | Myocardial reperfusion by early ST-segment resolution | According to the physician’s decision | Operator blinded to morphine use | NR |

| Bonin et al41 | France, retrospective | 1 | STEMI | NR | NR | No intervention | 969 | 60 (13) | MACE | According to the physician’s decision | NR | Adjusted for baseline patient clinical risk factors |

| Danchin et al42 | France, retrospective | 1 | STEMI | DAPT NR |

NR | No intervention | 3548 | 63 (12) | All-cause mortality | According to the physician’s decision | NR | NR |

| Farag et al43 | UK, prospective single centre | 30 days | STEMI | DAPT

|

5–10 mg IV | No intervention | 300 | 64 (13) | MACE and major bleeding | According to the physician’s decision | NR | NR |

| Franchi et al45 | USA, posthoc analysis of RCT | 1 | STEMI patients undergoing PPCI | Aspirin and ticagrelor | NR | No intervention | 46 | 59 | Asses the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics of escalating doses of ticagrelor | According to the physician’s decision | VerifyNow and VASP assays | Baseline Platelet reactivity unit values |

| Grendahl and Hansteen38 |

Norway, prospective | NR | Uncomplicated AMI<48 hour of symptoms | NR | 150 mg IV single dose | Placebo | 20 | NR | Assess the circulatory effects of morphine | NR | NR | NR |

| Johnson et al40 | UK, posthoc analysis | 1.5 | STEMI | Aspirin and prasugrel | NR | No intervention | 106 | 61.1 (11.7) | Platelet reactivity | According to the physician’s decision | Multiplate assay | NR |

| McCarthy et al44 | USA, retrospective | Hospital stay | STEMI and NSTE-ACS | Insufficient detail | NR | No intervention | 3027 | 62 (12) | Mortality | According to the physician’s decision | NR | Adjusted for baseline patient clinical risk factors and interventions used |

| Meine et al34 | USA, retrospective | 2.5 | NSTEMI | Insufficient detail | IV, no additional information | No intervention | 57 039 | 68 | Assess in-hospital death, recurrent myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock | According to the physician’s decision | CRUSADE database | Adjusted for baseline patient clinical risk factors, for provider and hospital characteristics |

| Puymirat et al35 | France, Retrospective | 2 months | STEMI patients with symptoms<48 hour | · 50% Aspirin · 71% Clopidogrel · 8% Prasugrel |

NR | No intervention | 2438 | 63 | Assess practices for myocardial infarction management in ‘real llife’ and with medium and long-term outcomes | According to the physician’s decision | FAST-MI 2010 database | Adjusted for baseline characteristics of the patients |

| Siller-Matula et al39 | Austria, prospective | 2 | STEMI patients treated with in-hospital loading dose of prasugrel | Aspirin and prasugrel | 5–15 mg IV single dose | No intervention | 32 | 60 (11) | Assess if abciximab is a bridging therapy to achieve adequate levels of platelet inhibition | NR | Multiplate | NR |

| Silvain et al10 (ATLANTIC study) | International, posthoc analysis of RCT | 14 hours | STEMI | Aspirin and ticagrelor | NR | No intervention | 37 | 56.2 (10.2) | Assess coronary reperfusion prior to percutaneous coronary interven- tion with prehospital or in-hospital ticagrelor 180 mg loading dose | NR | VerifyNow assay | NR |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; IV, intravenous; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; NR, not reported; NSTE-ACS, non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; RCT, randomised controlled trial; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; VASP, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein.

Morphine administration was variable across the included studies, with six of the observational studies10 34 35 40 42 45 not reporting information regarding dose and number or mode of administration. Among RCTs, morphine administration was intravenous or intramuscular at a dose between 2 and 10 mg, either in single or multiple administrations. The forms of antiplatelet therapy used across studies were varied, and firm conclusions cannot be made.

Risk of bias

We judged two of the five RCTs to be at a high overall risk of bias, one31 due to having unclear risk of bias in all but one domain, and the other29 due to a high risk of performance and attrition bias. All observational studies were at risk of bias due to confounding, and all but one36 were at moderate risk of selection of study results. Grendahl and Hansteen38 was additionally at moderate risk of bias due to measurement of outcome. Overall, two observational studies were at critical risk of bias,34 35 seven were at serious risk of bias36 38 39 and three were at a moderate risk of bias10 37 40 (online supplementary material).

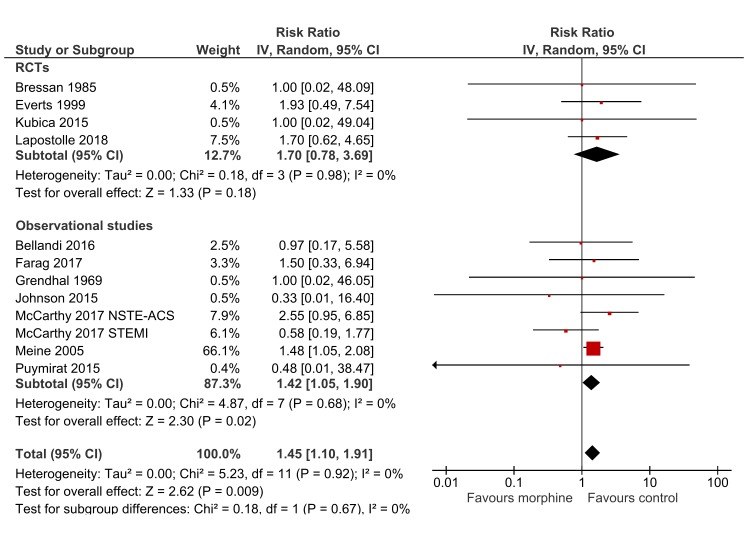

In-hospital mortality

Four RCTs (n=2237) and seven observational studies (n=63 112) contributed with data for this outcome. Adjusted pooled results showed an increased risk of in-hospital mortality in the morphine group (RR 1.45; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.91; I2=0%; figure 2). Subgroup analysis based on study design (p=0.67 for interaction; figure 2) and ACS subtype (STEMI RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.57 to 1.94; I2=0%; NSTE-ACS RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.14; I2=0% and p=0.25 for interaction) were both non-significant. Sensitivity analysis by excluding studies at critical risk of bias showed no differences between morphine and control (RR 1.41; 95% CI 0.87 to 2.27; I2=0%; n=5872 participants). The GRADE confidence in this estimate is low.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of in-hospital mortality according to morphine use, subgroups according to study design. IV, inverse variance; NSTE-ACS, non-ST elevated acute coronary syndrome; RCT, randomised controlled trials; STEMI, ST-elevated myocardial infarction.

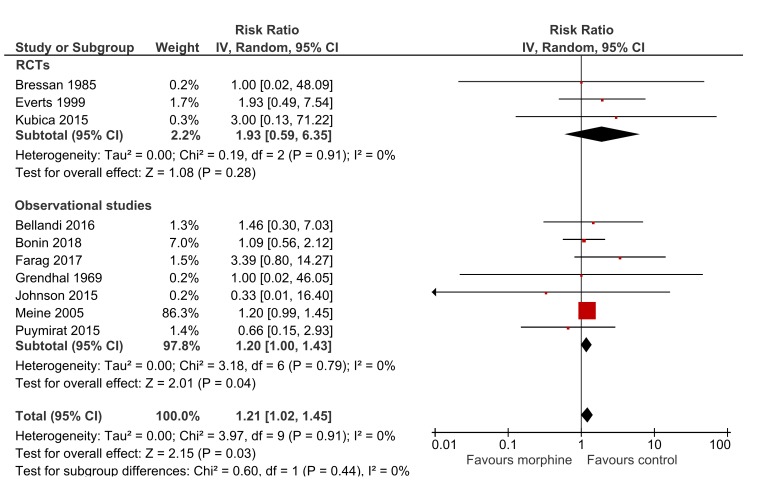

MACE

Three RCTs (n=375) and seven observational studies (n=61 054) contributed with data for this outcome. Adjusted pooled results showed an increased risk of MACE in the morphine group (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.45; I2=0%; figure 3). Subgroup analysis based on study design (p=0.44 for interaction; figure 3) and ACS subtype (STEMI RR 1.20; 95% CI 0.71 to 2.03; I2=0%; NSTE-ACS RR 1.21; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.46; I2=0% and p=0.98 for interaction) were both non-significant. Sensitivity analysis by excluding studies at critical risk of bias showed no differences between morphine and control (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.30; I2=0%; n=1952). The GRADE confidence in this estimate is low.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events) according to morphine use, subgroups according to study design. IV, inverse variance; RCTs, randomised controlled trails.

Bleeding

One RCT (n=70) and two observational studies (n=482) contributed with data for major bleeding, while three RCTs (n=375) and three observational studies (n=57 647) contributed with data for minor bleeding. No differences were found between morphine and control in the risk of either major (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.12; I2=0%) or minor (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.12; I2=40%) bleeding (online supplementary material). Subgroup analysis based on study design and ACS subtype were both non-significant (major bleeding: p=0.85 and p=0.85 for interaction, respectively; minor bleeding: p=0.20 and p=0.20 for interaction, respectively). The GRADE confidence in these estimates is low for major bleeding and very low for minor bleeding.

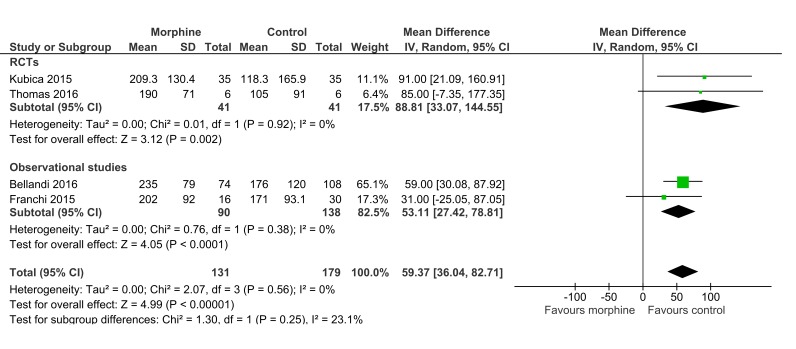

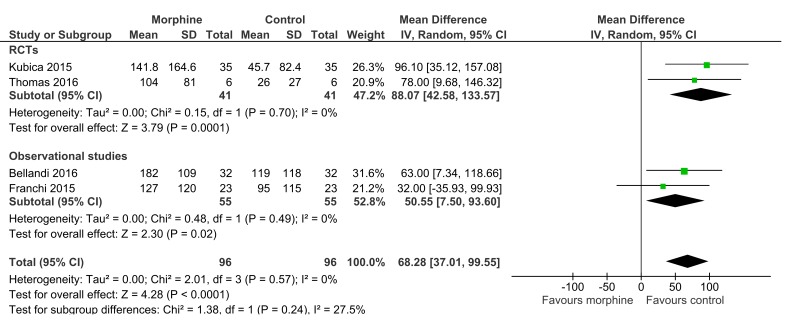

Platelet reactivity

We present data from 1 and 2 hours after morphine administration, as these are likely to be the most clinically meaningful timepoints. Two RCT (n=82) and two observational studies (n=228) contributed with data for this outcome. One hour after administration, morphine was associated with increased platelet reactivity, with an MD of 59.37 platelet reactivity units (PRU) (95% CI 36.04 to 82.71; I2=23%; figure 4). Two hours after administration, morphine remained associated with increased platelet reactivity (MD 68.28 PRU, 95% CI 37.01 to 99.55; I2=28%; figure 5). Subgroup analysis based on study design and ACS subtype were both non-significant at both timepoints (p=0.25 for interaction for both timepoints; p=0.24 for interaction for both timepoints, respectively). The GRADE confidence is high for this outcome at both timepoints.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of platelet reactivity at 1 hour postmorphine administration, using the VerifyNow method, subgroups according to study design. IV, inverse variance; RCTs, randomised controlled trails.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of platelet reactivity at 2 hours postmorphine administration, using the VerifyNow method, subgroups according to study design. IV, inverse variance; RCTs, randomised controlled trails.

We additionally pooled results using the three trials that reported results using the MEA method.30 39 40 These results were consistent with those using the VerifyNow method at both 1 hour (MD 27.80, 95% CI 16.03 to 39.57, I2=24%) and 2 hours after morphine administration (MD 19.99, 95% CI 1.52 to 38.46, I2=82%).

Additional outcomes

We found no differences associated with morphine use, namely regarding the risk of cardiogenic shock (RR 1.48; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.18; I2=0%), heart failure (RR 1.17; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.51; I2=33%), hypotension (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.74; I2=5%), nausea/emesis (RR 1.84; 95% CI 0.80 to 4.23; I2=44%), respiratory insufficiency (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.31 to 1.91; I2=0%) or stent thrombosis (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.92; I2=0%) (online supplementary material).

Discussion

Our main findings were as follows: (1) morphine was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and MACE; however, high risk of bias led to low confidence in the results; (2) morphine decreased the antiplatelet effect of P2Y12 inhibitors in the first hours of ACS, and the risk of bias associated with this objective measure was considered to be low.

Despite the widespread use of morphine in chest pain and anxiety relief in patients with ACS, conflicting data about its clinical impact has recently come to light.30 The activation of opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus decreases gut motility and secretion, inhibiting the activation of drugs whose action is directed at the P2Y12 protein and decreasing its absorption and bioavailability. Moreover, morphine is also known for its proemetic and antiperistaltic effects, which can further contribute to the decreased absorption of antiplatelet drugs.

This systematic review was planned and designed to evaluate the safety outcomes associated with morphine use in ACS. Pooled data RCTs and observational studies showed that treatment with morphine in patients with ACS is associated with a significant increase risk of in-hospital mortality, MACE and platelet reactivity.

We found that morphine decreased the antiplatelet effect of P2Y12 inhibitors in the first hours of ACS. The clinical significance of this increase is uncertain, as the magnitude of this change is less than the difference between ticagrelor and clopidogrel in ACS,46 but appears to be at least twice as large as the impact of esomeprazole on the pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel.47 This effect of morphine ceases to be relevant at around the 8 hour mark.36 This may contribute to a delay in the onset of acute medical treatment, a greater prothrombotic milieu and more myocardial damage in patients with ACS. What is more, the analgesic effect of morphine followed by a decreased sympathetic response of the patient, without directly reversing the cause of ACS, may lead physicians to underestimate the severity of the underlying disease and to postpone the referral to an invasive revascularisation procedure. All the above-mentioned reasons may contribute towards the increased risk of in-hospital mortality and MACE related to the use of morphine. In clinical practice, other opioid analgesic drug such as fentanyl can be used, and a recent trial showed that fentanyl treatment in ACS increased platelet reactivity compared with no treatment. Although this suggests a possible class-effect of opioids on antiplatelet drugs, the evidence is sparse and requires further investigation before firm conclusions can be made.48

Unexpectedly, we did not find an increased risk of nausea/emesis associated with morphine. This raises the likelihood that the reduction of gut secretion and motility is the core effect through which morphine decreases the activation of P2Y12 drugs.

With regard to platelet reactivity, we believe that the magnitude of the difference found supports a change in clinical practice, moving away from a recommendation to use morphine in ACS to recommending not using it routinely. The strength of this recommendation may be controversial due to the nature of the trials used and the other outcomes in this review not being statistically significant.

An important concern when combining randomised and observational data is the extent to which the participants and clinical setting are sufficiently similar to justify their pooling. On this account, the results of this review are robust since we found low heterogeneity across the outcomes of interest and the fact that none of the subgroup analyses comparing RCTs versus observational studies were statistically significant. Further proof of the consistency of the results is that no subgroup analysis showed a difference between STEMI and NSTE-ACS. However, due to concerns over risk of bias across studies, we assessed the certainty in the evidence as low, despite there being little concern regarding inconsistency, indirectness or lack of statistical power.

The key limitation of this review comes from the key limitation of most observational research, namely confounding. In a conservative approach, we attempted to minimise the impact of observational studies and their bias in the estimates by applying a correction factor previously used in other meta-analysis.26 27 Nevertheless, we must recognise that this adjustment is artificial and limits our results. Another limitation regards the possible differences in the doses and route of administration of morphine that were not available in most of the included studies.

Physicians may administer morphine to patients with more severe forms of chest pain, which may correspond to a more severe underlying ACS. This means that the increased risk of negative clinical outcomes could come as a result of patients being given morphine, or, alternatively, from the fact that morphine is usually reserved for the sickest patients. Because the included observational studies were substantially larger than the RCTs, including them in the meta-analysis could increase the risk of producing a biased result with an undue degree of statistical precision. To minimise this risk, we used methods to decrease the weight given to the largest and most biased studies, providing a more conservative estimate based on the available evidence. In doing so, we have produced the first and only systematic review to date that evaluates this highly relevant clinical question.

Conclusions

This systematic review raises concern about the use of morphine in patients with ACS and challenge the current clinical recommendations for its use in ACS. Most data come from studies at high risk of bias when evaluating the true effect of morphine in this setting. As such, a low-bias, adequately powered RCT designed to evaluate this question would be of significant scientific and clinical value. However, there is high certainty that morphine decreased the antiplatelet effect of P2Y12 inhibitors in the first hours of ACS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

UID/BIM/50005/2019, project funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT)/ Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (MCTES) through Fundos do Orçamento de Estado.

Footnotes

Contributors: DC and GSD conceived the idea for the protocol and made the main contribution to planning and preparation of timelines for its completion. DC and GSD planned the data extraction and statistical analysis, as well as of risk of bias, quality of evidence and completeness of reporting assessments. GSD designed the tables and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was then reviewed and amended by ANF, DC, FBR, FP, JC and JJF. All authors then approved the final written manuscript. DC is the guarantor for the work.

Funding: UID/BIM/50005/2019, project funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT)/ Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (MCTES) through Fundos do Orçamento de Estado.

Competing interests: JJF received speaker and consultant fees from Abbott, Bial GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal, Lundbeck, Merck-Serono, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, TEVA, and Solvay. FJP received speaker and consultant fees from Astra Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi and Sankyo Zeneca. All remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No unpublished data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Organization. WH. Cardiovascular Diseases. 2017. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/ (accessed 10 Oct 2017).

- 2. Wilkins E, Wilson L, Wickramasinghe K, et al. European cardiovascular disease statistics. Brussels: European Heart Network, 20172017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:e46–e215. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanchis-Gomar F, Perez-Quilis C, Leischik R, et al. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:256 10.21037/atm.2016.06.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI Focused Update on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1235–50. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal 2017. (published Online First: 10 Sep 2017). 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holzer P. Opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. Regul Pept 2009;155(1-3):11–17. 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giannopoulos G, Deftereos S, Kolokathis F, et al. P2Y12 Receptor antagonists and morphine: A dangerous liaison?. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Silvain J, Storey RF, Cayla G, et al. P2Y12 receptor inhibition and effect of morphine in patients undergoing primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The PRIVATE-ATLANTIC study. Thromb Haemost 2016;116:369–78. 10.1160/TH15-12-0944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1045–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Larsen PD, Holley AS, Sasse A, et al. Comparison of Multiplate and VerifyNow platelet function tests in predicting clinical outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Thromb Res 2017;152:14–19. 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Werkum JW, Harmsze AM, Elsenberg EH, et al. The use of the VerifyNow system to monitor antiplatelet therapy: a review of the current evidence. Platelets 2008;19:479–88. 10.1080/09537100802317918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins JPT AD, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies : Higgins JPT CR, Chandler J, Cumpston MS, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 520. Cochrane, 2017. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (updated Jun 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wallace BC, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, et al. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. 2012;49:15 10.18637/jss.v049.i05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dolan K, Martens HC, Schuurman PR, et al. Automatic noise-level detection for extra-cellular micro-electrode recordings. Med Biol Eng Comput 2009;47:791–800. 10.1007/s11517-009-0494-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deeks JJ. Issues in the selection of a summary statistic for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med 2002;21:1575–600. 10.1002/sim.1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Caldeira D, Alarcão J, Vaz-Carneiro A, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e4260 10.1136/bmj.e4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marques RP, Duarte GS, Sterrantino C, et al. Triplet (FOLFOXIRI) versus doublet (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) backbone chemotherapy as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2017;118:54–62. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sterne JAC EM, Moher D, Boutron I. Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases : Higgins JPT CR, Chandler J, Cumpston MS, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 520. Cochrane, 2017. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (updated Jun 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Veroniki AA, Rios P, Cogo E, et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs for neurological development in children exposed during pregnancy and breast feeding: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017248 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Efthimiou O, Mavridis D, Debray TP, et al. Combining randomized and non-randomized evidence in network meta-analysis. Stat Med 2017;36:1210–26. 10.1002/sim.7223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schünemann HJ OA, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, et al. Chapter 11: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the confidence in or quality of the evidence : Higgins JPT CR, Chandler J, Cumpston MS, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 520. Cochrane, 2017. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (updated June 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Everts B, Karlson B, Abdon NJ, et al. A comparison of metoprolol and morphine in the treatment of chest pain in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction--the MEMO study. J Intern Med 1999;245:133–41. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kubica J, Kubica A, Jilma B, et al. Impact of morphine on antiplatelet effects of oral P2Y12 receptor inhibitors. Int J Cardiol 2016;215:201–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bressan MA, Costantini M, Klersy C, et al. Analgesic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: a comparison between indoprofen and morphine by a double-blind randomized pilot study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1985;23:668–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lapostolle F, Van’t Hof AW, Hamm CW, et al. morphine and ticagrelor interaction in primary percutaneous coronary intervention in st-segment elevation myocardial infarction: ATLANTIC-Morphine. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2018:1–11. 10.1007/s40256-018-0305-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas MR, Morton AC, Hossain R, et al. Morphine delays the onset of action of prasugrel in patients with prior history of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost 2016;116:96–102. 10.1160/TH16-02-0102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meine TJ, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Association of intravenous morphine use and outcomes in acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. Am Heart J 2005;149:1043–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Puymirat E, Lamhaut L, Bonnet N, et al. Correlates of pre-hospital morphine use in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients and its association with in-hospital outcomes and long-term mortality: the FAST-MI (French Registry of Acute ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction) programme. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1063–71. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bellandi B, Zocchi C, Xanthopoulou I, et al. Morphine use and myocardial reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary PCI. Int J Cardiol 2016;221:567–71. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Franchi F, Rollini F, Cho JR, et al. Impact of escalating loading dose regimens of ticagrelor in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Results of a prospective randomized pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic investigation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:1457–67. 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grendahl H, Hansteen V. The effect of morphine on blood pressure and cardiac output in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Acta Med Scand 1969;186:515–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siller-Matula JM, Specht S, Kubica J, et al. Abciximab as a bridging strategy to overcome morphine-prasugrel interaction in STEMI patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;82:1343–50. 10.1111/bcp.13053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnson TW, Mumford AD, Scott LJ, et al. A study of platelet inhibition, using a ’point of care' platelet function test, following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-Elevation myocardial infarction [PINPOINT-PPCI]. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144984 10.1371/journal.pone.0144984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bonin M, Mewton N, Roubille F, et al. effect and safety of morphine use in acute anterior st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e006833 10.1161/JAHA.117.006833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Danchin N, Puymirat E, Cayla G, et al. One-year survival after st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction in relation with prehospital administration of dual antiplatelet therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11:e007241 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Farag M, Spinthakis N, Srinivasan M, et al. Morphine Analgesia Pre-PPCI Is associated with prothrombotic state, reduced spontaneous reperfusion and greater infarct size. Thromb Haemost 2018;118:601–12. 10.1055/s-0038-1629896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McCarthy CP, Bhambhani V, Pomerantsev E, et al. In-hospital outcomes in invasively managed acute myocardial infarction patients who receive morphine. J Interv Cardiol 2018;31:150–8. 10.1111/joic.12464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Franchi F, Rollini F, Cho JR, et al. Impact of morphine on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of ticagrelor in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:A1751–A51. 10.1016/S0735-1097(15)61751-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lhermusier T, Lipinski MJ, Tantry US, et al. Meta-analysis of direct and indirect comparison of ticagrelor and prasugrel effects on platelet reactivity. Am J Cardiol 2015;115:716–23. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fernando H, Bassler N, Habersberger J, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study to determine the effects of esomeprazole on inhibition of platelet function by clopidogrel. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:1582–9. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ibrahim K, Shah R, Goli RR, et al. Fentanyl delays the platelet inhibition effects of oral ticagrelor: full report of the pacify randomized clinical trial. Thromb Haemost 2018;118:1409–18. 10.1055/s-0038-1666862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025232supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)