Abstract

Objectives

Recent guideline changes for cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention medication have resulted in calls to implement shared decision-making rather than arbitrary treatment thresholds. Less attention has been paid to existing tools that could facilitate this. Decision aids are well-established tools that enable shared decision-making and have been shown to improve CVD prevention adherence. However, it is unknown how many CVD decision aids are publicly available for patients online, what their quality is like and whether they are suitable for patients with lower health literacy, for whom the burden of CVD is greatest. This study aimed to identify and evaluate all English language, publicly available online CVD prevention decision aids.

Design

Systematic review of public websites in August to November 2016 using an environmental scan methodology, with updated evaluation in April 2018. The decision aids were evaluated based on: (1) suitability for low health literacy populations (understandability, actionability and readability); and (2) International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS).

Primary outcome measures

Understandability and actionability using the validated Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printed Materials (PEMAT-P scale), readability using Gunning–Fog and Flesch–Kincaid indices and quality using IPDAS V.3 and V.4.

Results

A total of 25 unique decision aids were identified. On the PEMAT-P scale, the decision aids scored well on understandability (mean 87%) but not on actionability (mean 61%). Readability was also higher than recommended levels (mean Gunning–Fog index=10.1; suitable for grade 10 students). Four decision aids met criteria to be considered a decision aid (ie, met IPDAS qualifying criteria) and one sufficiently minimised major bias (ie, met IPDAS certification criteria).

Conclusions

Publicly available CVD prevention decision aids are not suitable for low literacy populations and only one met international standards for certification. Given that patients with lower health literacy are at increased risk of CVD, this urgently needs to be addressed.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, decision support, decision aid, prevention, shared decision making, health literacy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First systematic search to identify and evaluate freely available online CVD decision aids using the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS), the most credible and internationally recognised measure for evaluating patient decision aids.

Patient decision aids were evaluated using the multiple versions of IPDAS as well as the validated Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printed Materials measure relating to health literacy, extracted independently by two reviewers where discrepancies were resolved via discussion to reduce bias.

Google results are not replicable due to the changing nature of the search algorithm and websites; but using known repositories may assist researchers and clinicians to conduct similar searches.

We did not assess the accuracy of the information provided by these decision aids.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention is a key issue for primary care, as one of the most common problems managed in general practice1 and the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in developed nations.2 Clinical guidelines recommend lifestyle interventions with the addition of medication to lower blood pressure and/or cholesterol if CVD risk becomes high.3–5 However, recent guideline changes for CVD prevention medication have increasingly lowered the threshold for treatment: statin initiation has reduced from 20% absolute CVD risk over 10 years down to 10% in the UK and 7.5% in the USA6 7; and the latest US hypertension guidelines recommend a very low threshold of 130 mm Hg for blood pressure medication.8 These changes have led to wide debate in leading medical journals (eg, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet), with calls to implement shared decision-making based on both benefits and harms as well as patient preferences, rather than arbitrary treatment thresholds for CVD prevention.6–10

Shared decision-making is important in this context, because there are many ways to reduce risk and weighing up the benefits and harms of different options is dependent on individual preferences.7 9 For example, a 60-year-old female smoker with elevated blood pressure (130/80 mm Hg) and cholesterol (5/1.8 total/high-density lipoprotein mmol/L) will have a 10% chance of a CVD event in the next 10 years based on the Framingham model (see http://chd.bestsciencemedicine.com/calc2.html for risk and intervention estimates using different models). She may prefer to avoid the side effects and costs of medication and focus on changing her lifestyle,11 which could reduce her risk to 6% if she quit smoking, or 7% if she adopted a Mediterranean diet or increased her physical activity to high levels. Alternatively, she may be unwilling or unable to make these changes,11 and would prefer to reduce her risk to 7% with either low-moderate intensity statins12 or blood pressure lowering medication.13 Although these options have different relative risk reduction benefits, when the baseline CVD risk is only 10% the absolute benefit is very similar, so patient preferences must be taken into account.

Little attention has been paid to existing tools that could facilitate shared decision-making in this context. Decision aids are well established as an effective tool to help patients engage in shared decision-making about their health. International standards have been developed to ensure they provide evidence-based, unbiased information about benefits and harms, using multiple formats to enhance patient understanding (available at http://ipdas.ohri.ca/using.html).14 15 The latest Cochrane review on this topic found 105 RCTs evaluating decision aids, with positive effects on knowledge about options, value clarification and feelings of being better informed.16Patient decision aids for CVD prevention have been shown to improve uptake and self-reported adherence to preventive interventions17; however not all decision aids have reported similar effects on adherence. The Statin Choice decision aid aimed at CVD prevention in diabetes did not report similar adherence to statins but did report that patients accurately perceived their risk for heart attack.18

The availability of high quality, understandable health information is particularly important considering the burden of CVD is greater for people with low health literacy. This means they do not have adequate skills to access, understand or use resources to manage their own health. The majority of the general population falls into this category, and this is associated with less regular healthcare access, lower uptake of prevention services, poorer self-management, greater medication errors, worse CVD outcomes and increased all-cause mortality.19–21 It is therefore important to consider the needs of patients with low health literacy skills when developing online shared decision-making tools, which are likely to be accessed with little support from health professionals.

This study aimed to systematically review the online environment for patient decision aids relating to primary CVD prevention, and evaluate their quality based on international patient decision aid standards and health literacy criteria.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Decision aids were considered if they met all inclusion criteria: (1) focus on primary prevention (ie, not secondary prevention or treatment for established CVD), (2) provides information about blood pressure medication, cholesterol lowering medication and/or aspirin, (3) freely available, and (4) written in English. Exclusion criteria included: (1) could not be viewed due to technical problems after two attempts, (2) developed by a company with a vested interest in medication (eg, pharmaceutical) or (3) targeted at health professionals or clinicians.

Search methods

An environmental scan can be described as an efficient and organised means to collect specific information on a given topic/institution that is pertinent to its internal workings and external influences/surrounding.22 Part of the process involves a purposive approach to a search from which the search is then exploded. For this study, we identified known online decision aid repositories (see table 1) as the most likely sources to contain relevant information pertinent to this study. Our second source was from Google Australia.

Table 1.

List of known decision aid repositories

Two independent searchers (PP and RZ) were instructed to reset their cache in their web browsers before each Google search to minimise the effect of Google search optimisation. The final search terms after piloting included 11 for CVD/medication and 2 for decision aids. The lead researchers (CB, LT) and the two independent searchers agreed on 11 specific terms for CVD/medication: cardiovascular disease, heart disease, stroke, heart attack, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypercholesterolaemia, aspirin, blood pressure medication, cholesterol medication and statin, and two specific terms for decision aids: decision aid and decision support (see online supplementary appendix table A1 for search strategy). Additional terms were pilot tested before settling on the final list. A single CVD/medication term and a single decision aids term were combined for each search, resulting in 22 unique Google searches. The first 50 results for each unique Google search were exported (not including web advertisements), providing a pool of 1100 results to be title scanned for each searcher (2200 results in total). Scanning the first 100 search results for the first few searches found no additional resources after the first 50 results, so the cut-off of 50 was retained.

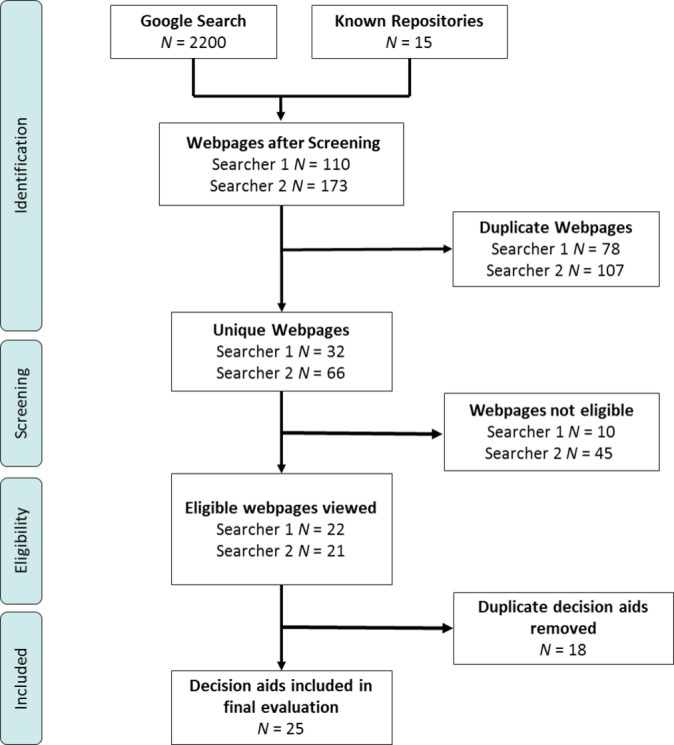

The two independent searchers conducted this search as part of a Master of Public Health degree capstone unit during August to November 2016. In March 2017, an independent rater (CB) reconciled these search results at the earliest stage feasible (see figure 1), and the original searchers completed any missing ratings for the final data set. Only websites that were still working when the third independent rater reconciled the lists were included. Duplicates were considered either as identical web addresses or identical PDFs.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis flow diagram of searcher results (searcher 1 PP, searcher 2 RZ).

Evaluation and data extraction

The two independent searchers rated the content of each decision aid using a validated tool to assess whether printed materials are suitable for people with low health literacy, the Patient Education Material Evaluation Tool for Print Materials (PEMAT-P).23 PEMAT-P includes two subscales: (1) understandability, which is a measure of how well a person is able to process and explain the key message of the material; and (2) actionability, which is a measure of how well a person is able to identify what to do based on the information presented. Items were rated on a binary scale (Yes/No) with some items provided a ‘Not Applicable’ option. Final understandability and actionability scores were calculated as a percentage of ‘Yes’ ratings for all items not including ‘not applicable’ ratings; higher percentages indicate better understandability or actionability. Intraclass correlations were calculated using SPSS V.25. For the two independent searchers, the intraclass correlation for final understandability scores was 0.51 and for actionability scores was 0.48. Conflicts for individual PEMAT-P items were therefore resolved by the third rater (MF, after discussion with CB) to finalise the PEMAT-P score for each individual decision aid. A threshold of 70% was used to determine whether the decision aid was understandable or actionable.21

Readability

Each decision aid’s readability was measured using the Gunning–Fog index, which is an index that estimates the formal years of (US) education an individual needs to understand the text.24 Scores range from 0 to 20 which corresponds to the US grade level that the text should be easily understood by, for example, a score of 6 would indicated the test should be easily understood by those educated to the sixth grade level in the US schooling system. The Flesch–Kincaid Reading Ease score was also calculated with higher scores indicating greater ease of comprehension. Scores range from 0 to 100 where a score of about 70–80 is the equivalent to school grade 7.25 The intraclass correlation between two independent ratings was high (Gunning–Fog Index was 0.91 and Flesch–Kincaid was 0.94) so the average of the two scores were used as the final index.

International Patient Decision Aids Standards checklist

The two independent researchers (PP and RZ) each completed a checklist based on version 3 of the International Patient Decision Aids Standards instrument (IPDASi) items, with discrepancies resolved by a third rater (MF, after discussion with CB). IPDASi V.3 has three domains: criteria used to be defined as a patient decision aid (seven items), criteria to lower risk of making a biased decision (nine items), other criteria indicating quality (thirteen items). Criteria used to be defined as a patient decision aid were rated on a yes/no scale and the other two domains were rated on a four-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree). In addition, two independent raters (PP and MF) used the IPDASi-Short Form (IPDASi-SF) to assess the same decision aids on a quantitative scale.14 Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). Total scores are calculated by the sum of all items and then converted into a value out of 100. Higher values indicate closer agreement with meeting the criteria of a decision aid. The IPDASi-SF is a shortened version of the third iteration of the IPDAS. The short form has demonstrated a 0.87 Pearson’s r correlation with the IPDASi 47-item version.14 In April 2018, the evaluation was repeated by two researchers (CB and MF) using IPDAS V.4, an updated version of IPDAS V.3 that reclassified the items into three domains with some revised wording and had collapsed some items into one. The new domains were qualifying, certification and quality. Qualifying criteria, if all met, identify the material as a decision aid. Certification criteria are those deemed essential to avoid harmful bias and all six criteria need to be met (ie, scored 3 or more) for the decision aid to be considered certified. Quality criteria on the other hand were items considered desirable but not essential to avoid harmful bias. All decision aids in the original evaluation were still publicly available at this time. Qualifying criteria are measured on a binary yes/no scale and certification and quality criteria are measured on a four-point Likert scale. To qualify as a decision aid, all six qualifying criteria must be met. To be certified as a decision aid, all six certifying criteria must score at least 3. Agreement for the qualifying items ranged from 64% to 100% and the average intraclass correlation coefficient between independent ratings for quality and certifying items were 0.16 and 0.34, respectively. Questions relating to screening tests were not used.

Patient and public involvement

The development of this research question was informed by the IPDAS, which has involved an extensive consultation process over many years to produce health decision-making tools that are useful and effective for patients. This study did not recruit patients or members of the public, so they were not specifically involved.

Results

The search of 15 known repositories and 2200 Google search results yielded 25 unique CVD prevention decision aids (see figure 1). Table 2 details the overall evaluation of the decision aids; and table 3 presents scores by individual decision aid. Online supplementary appendix table A2 provides the full IPDAS checklist item results and web archive URLs for the included decision aid webpages.

Table 2.

Evaluation for included decisions aids (n=25)

| Decision aid evaluation | ||

| Intervention options | Count (%) | |

| Medication | ||

| Cholesterol lowering | 14 (56) | |

| Blood pressure lowering | 5 (20) | |

| Aspirin | 8 (32) | |

| Lifestyle * | ||

| Any lifestyle change included | 7 (28) | |

| Quit smoking | 3 (12) | |

| Improve diet | 2 (8) | |

| Increase physical activity | 2 (8) | |

| Lose weight | 2 (8) | |

| IPDAS† | Median | Min–Max |

| V.3 | ||

| Criteria used to be defined as a patient DA | 5 or 71% | 3–6 or 43%–86% |

| Criteria to lower risk of making a biased decision | 33% | 11%–86% |

| Other criteria indicating quality | 82% | 0%–100% |

| V.4 | ||

| Qualifying criteria met (six items, yes or no) | 5 or 83% | 2–6 or 33%–100% |

| Certification criteria met (six items, score ≥3/4) | 3 or 50% | 1–6 or 17%–100% |

| Quality criteria met (23 items, score ≥3/4) | 7 or 30% | 1–12 or 4%–52% |

| Health literacy evaluation | Mean (SD) |

| PEMAT-P | |

| Understandability | 87 (7.1)‡ |

| Actionability | 61 (24.6)‡ |

| Readability | |

| Gunning–Fog | 9.9 (1.9) |

| Flesch–Kincaid | 61.8 (10.3) |

*Lifestyle changes will be less than the total sum of its subcategories as one decision aid may have multiple options.

†Percentages for the criteria to lower the risk of making a biased decision and criteria for indicating quality in IPDAS V.3 do not have counts because these items have an N/A response option, so using raw counts would not be an appropriate comparison.

‡These are mean and SD percentage values.

DA, decision aid; IPDAS, International Patient Decision Aids Standards; PEMAT-P, Patient Education Material Evaluation Tool for Print Materials.

Table 3.

Individual evaluation of included decision aids (n=25)

| ID | Patient Education Material Evaluation Tool for Print Materials ratings | International Patient Decision Aids Standards ratings | Readability ratings | |||

| Understandability (0–100) |

Actionability (0–100) |

V3-SF overall score (0–100) |

V4 quality criteria rated ≥3 (23 items) |

Gunning Fog (0–20) |

Flesch reading ease (0–100) |

|

| DA_01 | 94.1 | 66.7 | 60.9 | 10 | 8.3 | 63.9 |

| DA_02 | 93.8 | 83.3 | 72.7 | 9 | 9.9 | 63.7 |

| DA_03 | 92.9 | 71.4 | 81.3 | 11 | 7.8 | 73.9 |

| DA_04 | 92.9 | 71.4 | 81.3 | 12 | 8.8 | 70.9 |

| DA_05 | 92.9 | 71.4 | 81.3 | 6 | 8.5 | 65.4 |

| DA_06 | 85.7 | 60.0 | 51.6 | 4 | 8.0 | 69.7 |

| DA_07 | 92.9 | 16.7 | 64.8 | 7 | 10.9 | 55.4 |

| DA_08 | 85.7 | 20.0 | 64.8 | 7 | 9.7 | 63.4 |

| DA_09 | 82.4 | 66.7 | 65.6 | 9 | 10.3 | 59.4 |

| DA_10 | 75.0 | 60.0 | 46.1 | 1 | 11.8 | 46.1 |

| DA_11 | 76.9 | 60.0 | 46.9 | 2 | 11.1 | 48.6 |

| DA_12 | 88.2 | 83.3 | 61.7 | 7 | 7.2 | 76.0 |

| DA_13 | 88.2 | 83.3 | 61.7 | 7 | 7.2 | 75.7 |

| DA_14 | 88.2 | 83.3 | 61.7 | 7 | 7.1 | 76.3 |

| DA_15 | 81.3 | 33.3 | 63.3 | 7 | 11.1 | 63.4 |

| DA_16 | 81.3 | 33.3 | 63.3 | 7 | 11.1 | 62.3 |

| DA_17 | 81.3 | 33.3 | 63.3 | 7 | 11.4 | 61.9 |

| DA_18 | 73.3 | 60.0 | 71.9 | 10 | 13.7 | 37.1 |

| DA_19 | 80.0 | 60.0 | 71.9 | 11 | 13.2 | 40.4 |

| DA_20 | 94.1 | 100.0 | 69.5 | 9 | 11.8 | 56.7 |

| DA_21 | 81.3 | 33.3 | 69.5 | 8 | 11.4 | 63.0 |

| DA_22 | 87.5 | 20.0 | 65.6 | 7 | 11.6 | 57.8 |

| DA_23 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 78.9 | 6 | 9.0 | 66.9 |

| DA_24 | 94.1 | 80.0 | 41.4 | 3 | 7.7 | 66.5 |

| DA_25 | 94.1 | 80.0 | 53.1 | 6 | 10.0 | 60.5 |

Evaluation of the quality of the decision aids

For the version 3 IPDASi-SF (short form) scale, the Pearson’s r correlation between the two raters was 0.76 and the mean (SD) score was 64.56 (10.80) out of a maximum 100. For the version 3 IPDAS evaluation (see online supplementary appendix table A3 for individual scoring per item for each decision aid), none of the decision aids met all qualifying criteria to be defined as a patient decision aid and the median was 71% (5 out of 7 criteria met). None of the decision aids met all criteria to lower the risk of making a biased decision, and the median was 33%. None of the decision aids met all criteria to indicate quality, and the median was 85%. For the version 4 IPDAS evaluation (see online supplementary appendix table A4 for individual scoring per item for each decision aid), four decision aids met the criteria to qualify for a decision aid and the median was 83% (5 out of 6 criteria met) ranging from 2 to 6. One decision aid scored 3 or above on all six items to certified as a decision aid and the median was 50% (3 out of 6 items) ranging from 1 to 6. The median quality criteria that scored 3 or above was 30% (7 out of 23 criteria) ranging from 1 to 12 items.

A central component of decision aids is to present all options, risks and benefits in a balanced and unbiased way, with visual representation of numerical information. Nineteen decision aids provided only one intervention option (73%), whereas the remaining six provided 2–7 different options (27%). The presentation of harms versus benefits in icon arrays was highly variable. Icon arrays are graphic representations to show abstract probabilities as more concrete frequencies (eg, 2%=2 coloured dots out of 100 black dots), and are considered best practice for risk communication.26 Of the 12 decision aids that used icon arrays, 5 (42%) presented only benefits in icon arrays and 7 (58%) presented benefits and harms in icon arrays. Of the seven that presented benefits and harms in icon arrays, four (57%) combined benefits and harms in one icon array and three (43%) separated them. Of the four that combined benefits and harms in one icon array, one (25%) separated the benefits and harms and three (75%) overlapped the benefits and harms.

Evaluation of suitability for low health literacy populations

For the PEMAT-P evaluation, the decision aids generally scored well on understandability but lower on actionability. The average understandability score was 87% (SD=7.1%) and actionability was 61% (SD=24.6%). For readability, the average Gunning–Fog index was 9.9 (SD=1.9) and Flesch–Kincaid was 61.8 (SD=10.3), indicating that a US school grade of 9 is required to understand the information. The Pearson’s r correlation between understandability and readability was −0.60 for Gunning–Fog and 0.59 for Flesch–Kincaid.

Discussion

Principal findings

This review found 25 CVD prevention decision aids available to the public online, with the majority of them focussing on a single medication as the primary line of prevention against a potential future CVD event. Overall, the decision aids were very understandable but only had moderate actionability and a high readability level beyond the health literacy level of the general population. Most people would therefore have difficulty taking action based on the information in these decision aids, even though their primary purpose is to help the decision-making process. Of particular concern is that only 1 of the 25 decision aids met the most recent international criteria for certification, but the short form scores and quality checklist were reasonably high indicating decent quality overall. This means many decision aids would only require minor additions to reach certification standards; but the issues for low health literate patients would remain.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strengths of this study include a systematic review and evaluation process with multiple independent searchers/raters. The main limitation is the replicability of conducting a systematic search using online search engines like Google. The dynamic nature of the web with constant variation in website content and metadata means that no search is perfectly replicable even though the cache was cleared between search terms. However, the methods used are likely to have captured the most common and popular search results, since many duplicates were removed between the two searchers. Additional decision aids could have been found by a different searcher, search engine or geographical location and in other languages, which could produce different findings about the overall suitability for low health literate patients. However, this paper provides a list of known repositories of decision aids, including the primary source of IPDAS-assessed decision aids, to guide future researchers. This may improve the consistency of current and future findings. It also highlights the need for a central reputable location for decision aids that consumers could be referred to rather than search for their own.

Comparison to other research

The methods and findings of this study are comparable to two other environmental scans of prenatal decision aids, which also identified issues with presenting unbiased information about both benefits and harms.27 28 Other studies using PEMAT-P for patient education materials have found poor results (CVD decision aids in this study: 87% and 61%; CVD risk calculators: 64% and 19%; online heart failure websites: 56% and 35%; printed lifestyle information for chronic kidney disease: 52% and 37%; for PEMAT-P understandability and actionability scores, respectively).29–31 The IPDAS criteria for decision aid development may have led to higher quality patient education materials, but there is still room for improvement on actionability and readability levels.

Implications and future research

CVD prevention decision aids could be improved to better meet quality criteria and make them suitable for low health literacy populations. In particular, this needs to include: (1) a basic explanation of what CVD is and what CVD risk means, since the mechanism for how this leads to events like heart attack and stroke was rarely explained; (2) inclusion of both medication and lifestyle intervention options to enable a fully informed choice, as there tended to be a focus on single medication options; (3) balanced presentation of risks and benefits using visual communication aids such as icon arrays, since few decision aids used best practice risk communication strategies in an equal way for both the benefit and harm of options (eg, reduced chance of CVD event versus chance of side effects); and (4) more support for what actions to take based on the decision made.26

Several IPDAS items required substantial discussion between raters to decide on the best way to apply them consistently, indicating that further work is needed to provide a reliable tool for certifying decision aids. For example, decision aids that compared a single medication option versus doing nothing were easier to rate highly on balanced presentation than those with multiple options, even though the latter enables a more fully informed choice. In addition, the items did not cover: (1) health literate design issues (eg, use of white space, images that are consistent with text and clear direction for next steps); (2) assessment of the accuracy of the information provided (eg, whether the risks and benefits presented were based on the latest systematic review, if available); (3) ease of access for the intended audience, particularly for low health literacy populations; or (4) how effective the decision aid was, even when an evaluation had been conducted. Work on these issues is ongoing, with particular attention in the US following legislative changes to certify decision aids.32 The IPDAS criteria were more reliable when used by raters who were more familiar with decision aids at a later stage of the project, suggesting a need for structured training in using IPDAS rating scales.

Conclusion

To meet the needs of the general population who are likely to have low health literacy, CVD prevention decision aids need to improve actionability and readability, and better address basic certifying criteria such as explaining CVD and ensure that all options are presented in an unbiased way with visual support for benefits and harms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pauline Ledermann for assistance with calculating the readability scores.

Footnotes

Contributors: CB contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, data analysis and interpretation and drafting the manuscript. PP and RZ contributed to the methodology, data collection and revising the manuscript. MAF contributed to the data analysis and revising the manuscript. LT contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology and revising the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (Vanguard Grant 101326), the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and Therapeutic Guidelines (TGL/RACGP Research Grant TGL16b).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Website URLs containing the CVD Decision Aids are available in Supplementary Files. Descriptive and evaluative data are also available within Supplementary Files.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Cooke G, Valenti L, Glasziou P, et al. Common general practice presentations and publication frequency. Aust Fam Physician 2013;42:65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance (NVDPA). Guidelines for the assessment of absolute cardiovascular disease risk: Approved by the National Health and Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- 4. JBS3 Board. Joint British Societies’ consensus recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (JBS3). Heart 2014;100:ii1–67. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129:S49–73. 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Editorial. Statins for millions more? Lancet 2014;383:669–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldacre B. Statins are a mess: we need better data, and shared decision making. BMJ 2014;348:g3306.25134141 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, Qaseem A. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Hypertension limbo: balancing benefits, harms, and patient preferences before we lower the bar on blood pressure. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:369 10.7326/M17-3293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Montori VM, Brito JP, Ting HH. Patient-centered and practical application of new high cholesterol guidelines to prevent cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2014;311:465–6. 10.1001/jama.2014.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Redberg RF, Katz MH. Statins for primary prevention: the debate is intense, but the data are weak. JAMA 2016;316:1979–81. 10.1001/jama.2016.15085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonner C, Jansen J, McKinn S, et al. How do general practitioners and patients make decisions about cardiovascular disease risk? Health Psychol 2015;34:253–61. 10.1037/hea0000122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sundstrom J, Arima H, Woodward M, et al. Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet 2014;384:591–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61212-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;104:Cd004816 10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elwyn G, O’Connor AM, Bennett C, et al. Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument (IPDASi). PLoS One 2009;4:e4705 10.1371/journal.pone.0004705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, et al. Toward Minimum Standards for Certifying Patient Decision Aids: A Modified Delphi Consensus Process. Med Decis Making 2014;34:699–710. 10.1177/0272989X13501721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD001431 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheridan SL, Draeger LB, Pignone MP, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve use and adherence to effective coronary heart disease prevention strategies. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:331 10.1186/1472-6963-11-331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mann DM, Ponieman D, Montori VM, et al. The Statin Choice decision aid in primary care: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80:138–40. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adams RJ, Appleton SL, Hill CL, et al. Risks associated with low functional health literacy in an Australian population. Med J Aust 2009;191:530–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:97–107. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watkins I, Xie B. eHealth literacy interventions for older adults: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e225 10.2196/jmir.3318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Graham P, Evitts T, Thomas-MacLean R. Environmental scans: how useful are they for primary care research? Can Fam Physician 2008;54:1022–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:395–403. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gunning R. The technique of clear writing, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol 1948;32:221–33. 10.1037/h0057532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Trevena LJ, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Edwards A, et al. Presenting quantitative information about decision outcomes: a risk communication primer for patient decision aid developers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:S7 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leiva Portocarrero ME, Garvelink MM, Becerra Perez MM, et al. Decision aids that support decisions about prenatal testing for Down syndrome: an environmental scan. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2015;15:76 10.1186/s12911-015-0199-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donnelly KZ, Thompson R. Medical versus surgical methods of early abortion: protocol for a systematic review and environmental scan of patient decision aids. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007966 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cajita MI, Rodney T, Xu J, et al. Quality and health literacy demand of online heart failure information. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017;32:156–64. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morony S, Flynn M, McCaffery KJ, et al. Readability of Written Materials for CKD Patients: A Systematic Review. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:842–50. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bonner C, Fajardo MA, Hui S, et al. Clinical validity, understandability, and actionability of online cardiovascular disease risk calculators: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e29 10.2196/jmir.8538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pope TM, Lessler D. Revolutionizing informed consent: empowering patients with certified decision aids. Patient 2017;10:537–9. 10.1007/s40271-017-0230-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.