Abstract

Introduction

The global burden of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is steadily increasing. Experimental studies have demonstrated that a novel hormone secreted by bone cells, osteocalcin (OC), can stimulate beta-cell proliferation and improve insulin sensitivity in mice. Observational studies in humans have investigated the relationship between OC and metabolic parameters, and T2DM. Importantly, few studies have reported on the undercarboxylated form of OC (ucOC), which is the putative active form of OC suggested to affect glucose metabolism.

Objectives

We will conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to: (1) compare the levels of serum OC and ucOC between T2DM and normal glucose-tolerant controls (NGC); (2) investigate the risk ratios between serum OC and ucOC, and T2DM; (3) determine the correlation coefficient between OC and ucOC and fasting insulin levels, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance, haemoglobin A1c and fasting glucose levels and (4) explore potential sources of between-study heterogeneity. The secondary objective is to compare the serum OC and ucOC between pre-diabetes (PD) and NGC and between T2DM and PD.

hods and analysis

This study will report items in line with the guidelines outlined in preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology. We will include observational studies (cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies) and intervention studies with baseline data. Three databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCOPUS) will be searched from inception until July 2018 without language restrictions. Two reviewers will independently screen the titles and abstracts and conduct a full-text assessment to identify eligible studies. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus with a third reviewer. The risk of bias assessment will be conducted by two reviewers independently based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Potential sources of between-study heterogeneity will be tested using meta-regression/subgroup analyses. Contour-enhanced funnel plots and Egger’s test will be used to identify potential publication bias.

Ethics and dissemination

Formal ethical approval is not required. We will disseminate the results to a peer-reviewed publication and conference presentation.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017073127.

Keywords: osteocalcin, type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review will propose a sensitive search strategy to include more eligible observational studies (cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies) than previous meta-analyses.

The review will assess and synthesise data on both forms of osteocalcin (OC; total OC and undercarboxylated OC [ucOC]), potentially being more relevant to the endocrine function in humans.

The design of the review considers the early to late stages of diabetes, which will indicate whether the relationship between OC and impaired glucose metabolism is altered during progressively poorer glucose control.

Sources of heterogeneity will be explored using meta-regression/subgroup analyses.

The main limitation of the current study is only including observational studies (cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies).

Introduction

The disease burden attributed to diabetes is high. Currently, around 425 million people have diabetes, with 90% of these having type 2 diabetes (T2DM).1 It is estimated that by 2045, this figure will have increased to 629 million people.1 Patients with T2DM present increased levels of glucose than people with normal glycaemic metabolism. Also, those patients have increased risks of other complications, such as heart attacks, strokes, diabetic retinopathy and renal disease.2

Correspondingly, several organs become the targets to treat, prevent or predict diabetes, such as pancreatic beta cells, muscle, liver, adipose tissue, kidney, the gastrointestinal tract or the brain.3 Interestingly, a recent study has identified a new potential tissue to treat diabetes: the skeleton and bone. Increasing numbers of osteokines secreted by skeleton and bone exhibit regulatory function in glucose metabolism.3

Osteocalcin (OC) is an osteoblast-secreted protein that plays a role in the communication between the skeleton and glucose homeostasis. There are two forms of OC: undercarboxylated osteocalcin (ucOC) and carboxylated osteocalcin (cOC).4 cOC contributes to the extracellular bone matrix, while ucOC is likely the active form of OC in the circulation.5 Both cOC and ucOC are present in the circulation, and their combined amount is referred to as total osteocalcin (TOC).5 TOC is considered a marker of bone turnover.6

A potential endocrine function of OC was first suggested in 2007. Lee et al and Ferron et al reported OC-mediated glucose homeostasis via stimulating beta-cell proliferation and adiponectin secretion in mice.7 8 The endocrine actions of OC involve increasing insulin synthesis and secretion by beta-cells and improved insulin sensitivity by promoting adiponectin secretion in adipocytes.7 8 The high-fat diet experimental study revealed that bone could become insulin resistant by inhibiting the activation of OC.9 However, reported associations between OC and T2DM in humans have yielded conflicting results.10–13 Lerchbaum et al reported that high OC level was associated with reduced risk of developing T2DM in a population-based study (OR, 0.57; 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.70).14 In a cross-sectional study of patients with poorly controlled T2DM, Achemlal et al reported that serum levels of OC were significantly lower in T2DM compared with age-matched controls,15 while Bao et al observed that increased serum levels of OC were associated with improved glucose control.16 Yeap et al found that both TOC and ucOC were associated with reduced risk of diabetes in a cohort of community-dwelling elderly men (OR, 0.60; 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.72 for TOC, and OR, 0.55; 95% CI: 0.47 to 0.64 for ucOC).17 In contrast, a case-control study conducted by Zwakenberg et al with 1635 participants indicated a lack of association between TOC/ucOC and the risk of T2DM (OR, 0.97; 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.36 for TOC, and OR, 0.88; 95% CI: 0.61 to 1.27 for ucOC).18

Two previously published systematic reviews/meta-analyses reported decreased serum levels of TOC in people with T2DM compared with controls in 2015. However, these reviews only found a small number of published studies and did not investigate ucOC.19–21 The mean differences in T2DM compared with normal glucose tolerance controls from the three reviews showed similar results (−3.31 ng/mL (−4.04, –2.57) from Kunutsor et al; −2.87 ng/mL (−3.76,–1.98) from Liu C et al and −2.51 ng/mL (−3.01,–2.01) from Hygum et al).19–21 Both of the reviews by Kunutsor et al and Liu C et al only found a small number (n=4) of cohort studies.19 20 In addition, studies reporting the associations between ucOC and glucose homeostasis in T2DM have not been adequately meta-analysed.20

An increasing number of epidemiological studies have been continuously published in the recent 3 years following two systematic reviews/meta-analyses in 2015, signalling a need for up-to-date systematic review/meta-analysis. In 2017, Takashi et al showed that ucOC could predict insulin secretion in patients with T2DM.22 They conducted the study in 41 Japanese patients with T2DM with a mean age of about 59 years22 The result showed a correlation between ucOC and homeostatic model assessment of beta-cell function (r=0.36, P=0.011).22 In a cross-sectional study of 69 volunteers, OC was found to be suppressed with insulin resistance, regardless of obesity or fat mass at significantly lower levels shown in controls compared with T2DM or insulin resistant obesity.23 However, only a few interventional studies/clinical trials were found in our scope search in MEDLINE (online appendix 1). Only three clinical studies were conducted after 2015 and might be eligible for inclusion in the present review.24–26 Ghiraldini et al designed a clinical trial in 32 T2DM patients and 19 patients without diabetes. Baseline data indicated that OC levels were higher in systematically healthy patients than those with better-controlled T2DM while poorly controlled T2DM patients had the highest OC levels.26

bmjopen-2018-023918supp001.pdf (205.8KB, pdf)

Some observational studies have reported decreased OC concentrations in pre-diabetics (PD) compared with normal glucose tolerance controls, while Aoki et al indicated an increase in OC concentration during the early stage of diabetes.27–29 Therefore, conducting meta-analyses comparing the OC levels between PD and normal glucose controls and comparing OC levels between T2DM and PD may contribute to the investigation between OC and glucose homeostasis in patients with diabetes.

Another unsolved issue in the previously published meta-analyses is the high between-study heterogeneity. Previous reviews explored different sources of heterogeneity with modest success.19 20 Starup-Linde et al conducted subgroup analysis according to sex, age and menopausal status in women.30 Liu C et al attempted to explain the heterogeneity by sex and OC assay methods.20 Kunutsor et al conducted subgroup analyses according to study design and degree of confounders of risk estimates.19 Hygum et al performed a meta-regression analysis to investigate the extent to which heterogeneity was explained by haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels.21

Therefore, the present systematic review/meta-analysis will use a more comprehensive search strategy to identify more prospective studies, thereby increasing the statistical power. Second, we will search for studies reporting the association between ucOC and glucose metabolism. Third, we will identify studies comparing the OC concentrations between PD and normal glucose controls, and between T2DM and PD. Lastly, by systematically exploring potential sources of heterogeneity we may explain previous conflicting findings.

Objectives

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to: (1) compare the levels of serum OC and ucOC between T2DM and normal glucose-tolerant controls (NGC); (2) investigate the risk ratios between serum OC and ucOC, and T2DM; (3) determine the correlation coefficient between OC and ucOC, and fasting insulin levels, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), HbA1c and fasting glucose levels (FPG) and (4) explore potential sources of between-study heterogeneity. The secondary objective is to compare the serum OC and ucOC between PD and NGC, and between T2DM and PD.

Methods and analysis

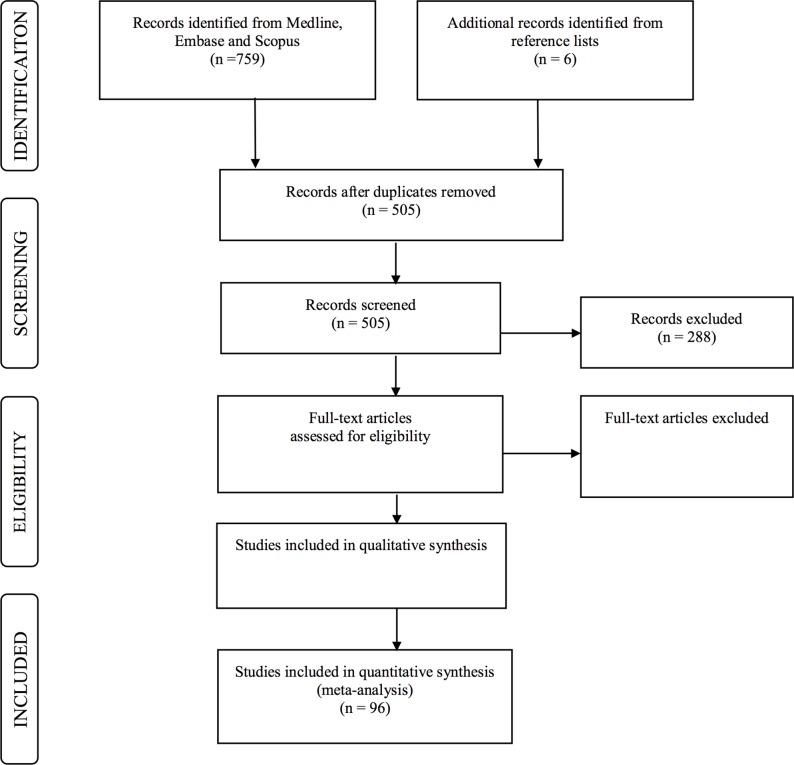

We designed this systematic review and meta-analysis in adherence to the guidelines of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) and meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE).31 32 The process of the proposed protocol is shown in figure 1, and the PRISMA checklist shown in online appendix 2.

Figure 1.

The process of the proposed protocol.

bmjopen-2018-023918supp002.pdf (348.3KB, pdf)

Patients and public involvement statement

There is no patient or public involved in this systematic review/meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria for studies included in the review

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants

Participants should be adult humans (older than 18 years old), with T2DM at the baseline or developed T2DM afterwards; not have any conditions that can affect bone metabolism or with medications that affect bone metabolism; and could be on anti-diabetic treatment.

Exclude:

Children or adolescents (younger than 18 years), and pregnant or lactating women due to altered bone turnover marker levels.

Patients with a disease that either affects bone metabolism or glucose metabolism.

Patients with type 1 diabetes and/or gestational diabetes as they are pathophysiologically different from patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Patients with Cushing’s disease or Cushing’s syndrome as they have disordered metabolism.

Patients with hormonal disorders. For instance, growth-hormone deficiency or excess.

Patients with hyperparathyroidism or hypoparathyroidism or other diseases that affect thyroid function due to increased osteocalcin (OC) levels and changes in metabolism.

Patients with liver dysfunction (alanine transaminase level >3 times upper limit of normal).

- Patients with impaired kidney function as described below:

- Chronic renal disease patients with glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min·1.73 m2 at stage four or five, or

- Chronic renal disease patients with serum creatinine level over 2.07 mg/dL, or renal osteodystrophy, or kidney transplant as 21%–50% of kidney transplant recipients may develop secondary hyperparathyroidism after kidney transplantation or when treated with dialysis or hemodialysis.

Patients with Paget’s disease as they have disordered bone metabolism.

Patients with osteomalacia as it is a severe bone disease and affects bone metabolism.

Patients with cancer or tumours. For example, bone cancer metastases could affect bone turnover marker levels.

Patients with HIV infection.

Patients with sepsis as they have disordered immune response caused by infections.

- Patients on medications that affect bone metabolism:

- Antiresorptive or anabolic therapy for osteoporosis and selective oestrogen receptor modulators (such as bisphosphonates, alendronate, etidronate, raloxifene, denosumab and teriparatide).

- Oestrogen replacement therapy.

- Glucocorticoids and thiazide diuretics.

Patients treated with surgery that directly affects hormone or thyroid function (ie, thyroidectomy, oophorectomy and hysterectomy).

Note:

We include intervention studies that reported baseline data of OC and T2DM. Accordingly, we will eliminate observational studies with more than 20% of the cohort taking above non-eligible therapy.

We included T2DM with diabetic medications, but they will be assessed using subgroup analysis by medication status. Anti-diabetic medications that affect OC/ucOC levels include insulin therapy, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and thiazolidinediones.

Study types

Observational studies are eligible for inclusion: cohort studies (both prospective and retrospective cohort studies), case-control studies and cross-sectional studies, reporting eligible exposure(s) and outcome(s).

We will exclude reviews, commentaries, short surveys, case reports, and letters.

Interventional studies (including randomised controlled trials) will be used if they provide eligible cross-sectional data at the baseline before intervention.

Exposure(s)

OC levels are identified from ELISA, electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, immunoradiometric assay, radioimmunoassay and hydroxylapatite binding assay. The standard unit for OC is ng/mL; thus, other presented groups for OC (eg, nmol/L) will be converted to ng/mL.

Measures of OC

Total serum OC levels (ng/mL).

ucOC levels (ng/mL).

OC categorised as low (reference) and high groups. Tertile, quartile or quantile are the common categories used for classifying different levels of TOC or ucOC.

Outcome(s)

Measures of T2DM

Diabetes status categorised as T2DM disease or normal controls (reference).

As some studies may categorise diabetes states as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), NIDDM will be used and presented as T2DM.

Exclude type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes as they are pathophysiologically different compared with T2DM.

Secondary outcome(s)

Impaired glucose tolerance/impaired fasting glucose: that is the pre-diabetic state with a higher risk of developing T2DM.

HbA1c levels categorised as T2DM, PD and healthy controls (reference) by HbA1c rates over 6.5%, between 5.7% and 6.5%, and below 5.7%, respectively.

Fasting plasma glucose levels categorised as diabetes, PD and healthy controls (reference) by FPG levels over 126 mg/dL, between 100 and 126 mg/dL, and below 100 mg/dL, respectively.

Study design

Search strategies

A comprehensive literature search within MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCOPUS databases will be conducted to source all possible relevant studies for the present review. There is no language restriction, and non-English articles will be translated when possible and evaluated for eligibility. There is no time restriction. We may include conference proceedings and abstracts if necessary. We will further conduct reference list searches of each available paper. If duplicate publications of the same study are retrieved, the most relevant and up to date paper with more complete data will be included. The detailed search strategy is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Detailed search strategy in databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCOPUS

| MEDLINE (Ovid SP) | EMBASE (Ovid SP) | SCOPUS |

|

|

(KEY (’osteocalcin') OR KEY (’bone AND gla AND protein') OR KEY (’bone AND turnover AND markers')) AND (KEY (’diabetes AND mellitus') OR KEY (’hemoglobin AND a1c') OR KEY (’fasting AND plasma AND glucose')) AND KEY (’human') AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, ‘ar’)) |

Process for selecting studies

One author will set-up the search strategy and store the search results in Endnote X7. The search strategy and recorded search results will then be checked by another investigator. Two or more independent investigators will perform the abstract screening (to remove duplicate records of the same report and to include eligible articles), and full-text assessment (to acquire full-texts of available studies and to construct citation lists of eligible items). If a discrepancy arises, the disagreement will be discussed with investigators by email or face-to-face meetings before reaching a final decision.

Data extraction

Two authors will independently extract data from studies that are eligible for full-text assessment. If any discrepancy arises, a third reviewer will examine the data. All extracted data will be saved in an Excel spreadsheet.

Eligible extracted items: author and publication year, study design, study base, sample size, sex and postmenopausal status in females, age, ethnicity, country, OC assay methods, obesity measurements (body mass index or waist circumference), duration of diabetes, anti-diabetic medications status, vitamin K supplementation/anti-vitamin K drugs, vitamin D supplementation, TOC/ucOC levels in groups, any risk estimate between TOC/ucOC and T2DM, any association between TOC/ucOC and HbA1c and/or FPG in T2DM, any association between TOC/ucOC and PD and/or impaired glucose tolerance/impaired fasting glucose, any association between TOC/ucOC and standard glucose controls, and any association between TOC/ucOC and HOMA-IR or HOMA-beta in T2DM.

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality will be assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Cohort and case-control studies can be assessed by three main parts in the NOS: selection, comparability and outcome/exposure.33 The maximum score is nine points.33 A higher score indicates better methodological quality of the individual study.33 Cross-sectional studies can be assessed using the modified NOS.34 The maximum score is 10 points for the modified NOS, representing the highest quality.34 The quality assessment template can be found in the supplementary materials (online appendix 3).

bmjopen-2018-023918supp003.pdf (442.8KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Mean differences with 95% CI will be calculated between T2DM and NGC, between PD and NGT, and between T2DM and PD. Estimates of effect size will be expressed as relative risk with 95% CI for cohort studies and OR with 95% CI for case-control and cross-sectional studies. OR is expressed as one increased SD of OC to the risk of developing T2DM. Papers reporting other forms of OR will be translated to per increased SD of OC if a logistic regression model is used. Pearson’s correlation coefficient will be analysed by investigating the relationships between TOC or ucOC and fasting insulin levels. Studies that only have medians and ranges or IQRs will be transformed to means and SD.35 36 Furthermore, log-transformed data will be converted to raw statistics before subjecting to analyses.37 We will assess publication bias of mean differences and risk estimates by visual inspection of the funnel plots38 39 Egger’s test will be used to assess the publication bias when there is a large number of studies.38 We will evaluate heterogeneity employing the I2 statistic by study ID which quantifies inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta-analysis.40 I2 represents the degree of heterogeneity. I2 thresholds of 0%–40%, 30%–60%, 50%–90% and 75%–100% indicate possibilities of low, moderate, substantial and considerable heterogeneity, respectively.40 It is suggested to use Rstudio for conducting meta-analyses (V.1.1.419-2009-2019; RStudio). The ‘metafor’ package will be used to perform meta-regression analyses, meta-bias analyses and for assessing heterogeneities.41 Each p value of <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Meta-regression/subgroup analysis

Meta-regression analysis and subgroup analysis will be applied to assess the sources of heterogeneity. Meta-regression will be used for continuous factors such as age, sample size and proportion of postmenopausal women. We will use subgroup analyses to identify potential sources of clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity for categorical variables. We will also generate mix-effect models to evaluate the influence of multiple factors on the effect size. Random-effects models will be used, and p values of <0.01 will be considered statistically significant for subgroup analyses. Pre-planned subgroup analyses to explore statistical heterogeneity will include stratification by:

Subgroups based on study design.

Subgroups based on age.

Subgroups based on sex. In addition, a subset based on menopausal status will be assessed among females.

Subgroups based on ethnicity or race.

Subgroups based on diabetic status (normal, PD, T2DM).

Subgroups based on anti-diabetic medication status in T2DM.

Subgroups based on obesity measurements (body mass index/waist circumference).

Subgroups based on OC assay methods.

Subgroups based on fasting measures and spot measures.

Subgroups based on vitamin K supplementation/anti-vitamin K drugs or vitamin D supplementation if data are available.

Publication bias and confidence in cumulative evidence

Publication bias assessment is based on graphical test (funnel plots) and Egger’s and Begg’s tests.38 39 The asymmetry of the funnel plot suggests a higher risk of publication bias and vice versa.38 Statistically, Egger’s and Begg’s tests will be conducted using RStudio.

We will provide assurance of the quality of our results by applying the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool. We will also present an evidence profile summary using GRADEpro software (http://ims.cochrane.org/gradepro). The quality checklist includes the following items: risk of bias assessment, consistency of results, directness of evidence and precision of the results.

Discussion

The current systematic review/meta-analysis constitutes an update and improvement to the current literature in several ways. First, we will provide more evidence compared with previous investigations in analysing the potential role/s OC plays in T2DM by increasing the number of eligible studies included in our up-to-date analysis. Second, we will investigate the sources of heterogeneity, explicitly by an increase in the number of factors such as age, sex, postmenopausal status in women, study design, ethnicity or regions, OC assays and medications on T2DM. This comprehensive analysis of heterogeneity may uncover the factor(s) responsible for the differences among already published studies. Third, we will produce a report not only on TOC levels, but also on ucOC levels. By including investigations on ucOC, we can determine the endocrine roles of both OC and ucOC in humans, if any. In addition, investigating the relationship in a subgroup of patients with PD will provide more details regarding the influence of OC (or ucOC) on glucose levels in a progressive T2DM status. The major limitation of this review is that we will only be including observational studies as there is insufficient evidence from clinical trials, which will restrict study results in specific analyses. According to the search results for clinical studies, if there are any eligible interventional studies, we will include them but only use the baseline data in which case we will regard those studies as cross-sectional studies. Despite this disadvantage, there are still a large number of studies that could be used to pool a quantitative analysis and provide evidence according to concerns with heterogeneity. Our review will contribute to public health and clinical research for further investigations regarding the gap in the current literature.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study concept and design. YHL led the writing of the manuscript and is the primary designer of the protocol under the guidance of AP. TBS, JL, KB and AP conceived the conceptual ideas presented in the manuscript. YHL and XYL collected the data for screening. YHL, XYL, JL, KB, TBS and AP revised the protocol critically. All authors read and approved the revised version and final supported versions.

Funding: Armando Teixeira-Pinto is partially supported by the NHMRC Program Grant BeatCKD [APP1092957].

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The present study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal when completed. If appropriate, we will present novelty findings at a relevant conference.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes ATLAS - 8th edition. 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/across-the-globe.html (Cited 2 Aug 2018). [PubMed]

- 2. World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes-Isbn. 2016;978:88 http://www.who.int/about/licensing/%5Cnhttp://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. mei LD, Mosialou I, min LJ. Bone: Another potential target to treat, prevent and predict diabetes. Diabetes, Obes Metab. 2018;20:1817–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Price PA. Gla-containing proteins of bone. Connect Tissue Res 1989;21(1-4):51–60. 10.3109/03008208909049995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wei J, Karsenty G. An overview of the metabolic functions of osteocalcin. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2015;13:180–5. 10.1007/s11914-015-0267-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown JP, Albert C, Nassar BA, et al. Bone turnover markers in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Biochem 2009;42:929–42. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 2007;130:456–69. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferron M, Hinoi E, Karsenty G, et al. Osteocalcin differentially regulates beta cell and adipocyte gene expression and affects the development of metabolic diseases in wild-type mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:5266–70. 10.1073/pnas.0711119105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wei J, Ferron M, Clarke CJ, et al. Bone-specific insulin resistance disrupts whole-body glucose homeostasis via decreased osteocalcin activation. J Clin Invest 2014;124:1781–93. 10.1172/JCI72323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hinoi E, Gao N, Jung DY, et al. The sympathetic tone mediates leptin’s inhibition of insulin secretion by modulating osteocalcin bioactivity. J Cell Biol 2008;183:1235–42. 10.1083/jcb.200809113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iki M, Tamaki J, Fujita Y, et al. Serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin levels are inversely associated with glycemic status and insulin resistance in an elderly Japanese male population: Fujiwara-kyo Osteoporosis Risk in Men (FORMEN) Study. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:761–70. 10.1007/s00198-011-1600-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levinger I, Zebaze R, Jerums G, et al. The effect of acute exercise on undercarboxylated osteocalcin in obese men. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:1621–6. 10.1007/s00198-010-1370-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brennan-Speranza TC, Conigrave AD. Osteocalcin: an osteoblast-derived polypeptide hormone that modulates whole body energy metabolism. Calcif Tissue Int 2015;96:1–10. 10.1007/s00223-014-9931-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lerchbaum E, Schwetz V, Nauck M, et al. Lower bone turnover markers in metabolic syndrome and diabetes: the population-based Study of Health in Pomerania. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015;25:458–63. 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Achemlal L, Tellal S, Rkiouak F, et al. Bone metabolism in male patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Rheumatol 2005;24:493–6. 10.1007/s10067-004-1070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bao YQ, Zhou M, Zhou J, et al. Relationship between serum osteocalcin and glycaemic variability in Type 2 diabetes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2011;38:50–4. 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05463.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yeap BB, Alfonso H, Chubb SA, et al. Higher serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin and other bone turnover markers are associated with reduced diabetes risk and lower estradiol concentrations in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:63–71. 10.1210/jc.2014-3019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zwakenberg SR, Gundberg CM, Spijkerman AM, et al. Osteocalcin is not associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes: findings from the EPIC-NL study. PLoS One 2015;10:1–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kunutsor SK, Apekey TA, Laukkanen JA. Association of serum total osteocalcin with type 2 diabetes and intermediate metabolic phenotypes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational evidence. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:599–614. 10.1007/s10654-015-0058-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu C, Wo J, Zhao Q, et al. Association between serum total osteocalcin level and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Horm Metab Res 2015;47:813–9. 10.1055/s-0035-1564134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hygum K, Starup-Linde J, Harsløf T, et al. a state of low bone turnover-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 2017;176:R137–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takashi Y, Koga M, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin can predict insulin secretion ability in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2017;8:471–4. 10.1111/jdi.12601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tonks KT, White CP, Center JR, et al. Bone turnover is suppressed in insulin resistance, independent of adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:1112–21. 10.1210/jc.2016-3282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu C, Jiang D. High glucose-induced LIF suppresses osteoblast differentiation via regulating STAT3/SOCS3 signaling. Cytokine 2017;91:132–9. 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lasco A, Morabito N, Basile G, et al. Denosumab inhibition of RANKL and insulin resistance in postmenopausal women with Osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2016;98:123–8. 10.1007/s00223-015-0075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ghiraldini B, Conte A, Casarin RC, et al. Influence of glycemic control on peri-implant bone healing: 12-month outcomes of local release of bone-related factors and implant stabilization in type 2 diabetics. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2016;18:801–9. 10.1111/cid.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iglesias P, Arrieta F, Piñera M, et al. Serum concentrations of osteocalcin, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and beta-CrossLaps in obese subjects with varying degrees of glucose tolerance. Clin Endocrinol 2011;75:184–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aoki A, Muneyuki T, Yoshida M, et al. Circulating osteocalcin is increased in early-stage diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;92:181–6. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liang Y, Tan A, Liang D, et al. Low osteocalcin level is a risk factor for impaired glucose metabolism in a Chinese male population. J Diabetes Investig 2016;7:522–8. 10.1111/jdi.12439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Starup-Linde J, Eriksen SA, Lykkeboe S, et al. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in diabetes patients–a meta-analysis, and a methodological study on the effects of glucose on bone markers. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1697–708. 10.1007/s00198-014-2676-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wells GA, Shea B, O’connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Canada: Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147601 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:1–13. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Higgins JP, White IR, Anzures-Cabrera J. Meta-analysis of skewed data: combining results reported on log-transformed or raw scales. Stat Med 2008;27:6072–92. 10.1002/sim.3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marcon E, Hérault B. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 2015;36 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023918supp001.pdf (205.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023918supp002.pdf (348.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023918supp003.pdf (442.8KB, pdf)