Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether ETS-related gene (ERG) expression can be used as a biomarker to predict biochemical recurrence and prostate cancer-specific death in patients with high Gleason grade prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) as monotherapy.

Methods

A multicentre retrospective cohort study identifying 149 patients treated with primary ADT for metastatic or non-metastatic prostate cancer with Gleason score 8–10 between 1999 and 2006. Patients planned for adjuvant radiotherapy at diagnosis were excluded. Age at diagnosis, ethnicity, prostate-specific antigen and Charlson-comorbidity score were recorded. Prostatic tissue acquired at biopsy or transurethral resection surgery was assessed for immunohistochemical expression of ERG. Failure of ADT defined as prostate specific antigen nadir +2. Vital status and death certification data determined using the UK National Cancer Registry. Primary outcome measures were overall survival (OS) and prostate cancer specific survival (CSS). Secondary outcome was biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS).

Results

The median OS of our cohort was 60.2 months (CI 52.0 to 68.3). ERG expression observed in 51/149 cases (34%). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis showed no significant association between ERG expression and OS (p=0.41), CSS (p=0.92) and BRFS (p=0.31). Cox regression analysis showed Gleason score (p=0.003) and metastatic status (p<1×10-5) to be the only significant predictors of prostate CSS.

Conclusions

No significant association was found between ERG status and any of our outcome measures. Despite a limited sample size, our results suggest that ERG does not appear to be a useful biomarker in predicting response to ADT in patients with high risk prostate cancer.

Keywords: prostate disease, cancer genetics, therapeutics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This observational study consists of a large cohort of solely high-risk cancers treated with initial androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) as monotherapy with subsequent vital status determination through a UK national death certification registry.

The association between ETS-related gene (ERG) expression and oncological survival is explored for the first time in patients on ADT as monotherapy.

Our study population is of limited sample size. Accuracy of results may be reduced from lack of covariates gained through retrospective data collection.

Determination of ERG status is limited to immunohistochemical detection of the protein without classification of its mutation at a genomic level.

Introduction

The development of castration resistance is a major clinical hurdle in patients with advanced prostate cancer and is taken as a marker of impending mortality. Early identification of patients who develop castrate resistant prostate cancer can be clinically useful in enabling early aggressive treatment and therefore in reducing cancer-related deaths.

A recurrent gene fusion event involving the 3’ end of ERG (ETS-related gene) to 5’ TMPRSS2 (transmembrane protease, serine 2)1 is one of the most frequently occurring genetic aberrations in prostate cancer2 but its prognostic value is still being explored.3 A meta-analysis evaluating the role of TMPRSS2:ERG fusion protein in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy found no association with biochemical recurrence or lethal disease.4

Given that TMPRSS2:ERG is androgen regulated,5 its association with oncological outcomes in patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is possible. ERG expression inversely correlates with the levels of androgen receptor protein in the cell and may exert a selective pressure for the development of a castrate-resistant state.6 Furthermore, androgen-regulated ERG expression appears to persist following the development of castration resistance.7

In vivo validation of ERG’s metastatic influence has been controversial. Scheble VJ et al had shown a greater proportion of castration resistant metastatic prostate cancer driven by ERG negative tumours,8 while Perner S et al had observed a greater predilection to metastases in fusion positive foci.9

The aim of this study is to explore a possible association between ERG expression status and oncological outcomes in high grade and advanced prostate cancer patients treated by ADT as monotherapy. The primary end points are overall survival (OS) and prostate cancer specific survival (CSS). The secondary end point is biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS).

Patients, materials and methods

Data collection, study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were identified from the pathology databases at two large neighbouring hospitals, Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust in London, UK, between January 1999 and August 2006. All patients treated with primary ADT were included in the study. Those were identified among patients with a total Gleason score of 8–10. For each patient, the initial assigned treatment was identified using electronic and paper records. Patients with both metastatic and non-metastatic disease were included in the study. Clinical data collected included the age at diagnosis, the assigned treatment at diagnosis, ethnicity (Caucasian, Afro-Caribbean, or other), Charlson comorbidity score,10 date of diagnosis, total modified International Society of Urologic Pathology 2005 Gleason Score, radiological evidence of metastasis at diagnosis, history of previous prostate cancer treatment, and serial prostate specific antigen (PSA) values (ng/mL). Patients were excluded from the study for any missing data, if they did not receive ADT or were planned to receive other adjuvant therapies such as radiotherapy. Data on unplanned adjuvant therapy following ADT were not collected due to incomplete follow-up data. The primary end points were OS and CSS. The secondary end point was BRFS.

Vital status and death certification data

Patient vital status data were retrieved from the National Cancer Registry in Public Health England.11 Following institutional approval, unique patient National Health Service numbers were linked to vital status, dates of death and ICD-10 codes on the immediate cause of death (cause 1a), other diseases or conditions leading to 1a (causes 1b and 1 c), underlying cause of death and other significant conditions not directly related to death (cause 2).12 A prostate cancer death was defined as any death stating ‘Prostate Cancer’ in any of causes 1a, 1b, 1 c or an underlying cause. Biochemical recurrence was defined as an increase of more than 2 ng/mL from the PSA nadir value with censoring on the date when PSA rose more than 2 ng/mL above nadir.13

Prostate cancer sample collection, tissue processing and immunohistochemical staining

Prior to retrieval of archived prostate tissue samples, available H&E-stained slides were examined by two consultant histopathologists to select one tissue block for each patient based on the largest cancer volume. Specimen numbers were used to retrieve the corresponding paraffin-embedded blocks from the archives, and 3 µm sections were cut from each block using the Rotary Microtome HM 32S. Immunohistochemistry was performed in batches using the Ventana BenchMark ULTRA IHC/ISH automated stainer (Ventana Medical Systems). Deparaffinisation of the sections was carried by warming up the slides at 72°C in Ventana EZ Prep solution. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using the Ventana inhibition kit and antigen retrieval was carried out by incubating the slides in Cell Conditioning solution-1 and subsequently heating at 100°C for 8 min, then 100 µL of Anti-ERG (EPR3864) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody was applied on each slide for 32 min. Visualisation was performed using anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labelled secondary antibody and 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) chromogen (Roche/Ventana Ultra View DAB kit). The slides were washed and counterstained with Ventana Haematoxylin and Ventana Bluing Solution.

The IHC nuclear reactivity for ERG protein expression in the vascular endothelial cells was used as positive internal controls.14 Tests were repeated when endothelial cells failed to stain with ERG antibody (see supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2018-025161supp001.pdf (918.8KB, pdf)

H-scoring

Semiquantitative IHC analysis of ERG expression was conducted by the H-scoring system.14 Percentages of prostate cancer cells with positive and negative nuclear ERG staining were assessed at high magnification for each sample by two consultant histopathologists. The H-score was calculated as: 3× percentage cells with strong ERG expression +2× percentage of cells with intermediate ERG expression +1× percentage of cells with weak ERG expression.15 The total H-score per sample therefore ranged from 0 to 300. H-scores were classified as negative (0–50), weakly positive (51–100), moderately positive (101–200) or strongly positive (201–300) (see online supplementary figure 2).

Validation of antibody clone against an alternative anti-ERG antibody

Alternative ERG staining was carried out on selected cancer tissue samples using an alternative monoclonal ERG antibody (clone 9FY, ab139431). The results are depicted on the photomicrographs shown in supplementary figure 3.

Statistical methods

OS and CSS were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate analysis of survival was performed using the log-rank method. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to assess OS, CSS and BRFS with adjustments for ERG expression, age, ethnicity, Gleason score, PSA, presence of metastasis at presentation and Charlson comorbidity score. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS V.22, Graphpad Prism V.5.0 and Microsoft Excel software.

Patient and public involvement

No patients and public persons were involved in the commencement of this research.

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 527 patients with high Gleason score prostate cancer were diagnosed on biopsy, of which 169 patients were assigned to primary ADT as monotherapy. Exclusion of patients was due to tissue samples being unavailable (n=4), lack of vital status data output from the National Cancer Registry (n=4) or one or more missing clinical parameters (n=12). Complete data were available for 149 patients which formed the study population.

Mean follow-up was 46.5 (±25.2) months. Fifty-nine patients (40%) had metastatic disease at presentation. The clinical characteristics of the cohort are shown in (table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population stratified by ERG expression status (p values obtained by χ2 or *t-tests)

| ERG negative | % | ERG positive | % | P value | |

| (n=98) | (n=51) | ||||

| Mean age (±SD), years | 72.3 (±8.3) | 75.5 (±8.6) | 0.03* | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 51 | 52 | 37 | 73 | 0.04 |

| Afro-Caribbean | 41 | 42 | 11 | 22 | |

| Other | 6 | 6 | 3 | 6 | |

| Gleason score | |||||

| 8 | 22 | 52 | 13 | 25 | 0.88 |

| 9 | 71 | 42 | 36 | 71 | |

| 10 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| PSA (±SD), ng/mL | 1378 (±10849) | 283 (±1203) | 0.48* | ||

| <10.00 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0.38 |

| 10–19 | 17 | 18 | 7 | 14 | |

| 20–49 | 24 | 25 | 18 | 36 | |

| 50–99 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 20 | |

| ≥100 | 39 | 40 | 11 | 22 | |

| Metastasis | |||||

| No | 60 | 61 | 30 | 59 | 0.78 |

| Yes | 38 | 39 | 21 | 41 | |

| Charlson comorbidity | |||||

| 0 | 43 | 44 | 25 | 49 | 0.05 |

| 1 | 30 | 31 | 6 | 12 | |

| 2 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 22 | |

| ≥3 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 18 | |

| Follow-up (±SD), months | 47.9 (±25.5) | 43.7 (±24.9) | 0.34 | ||

| Deaths | |||||

| All causes | 46 | 47 | 28 | 55 | 0.39 |

| Prostate cancer specific | 29 | 30 | 17 | 33 | 0.71 |

ERG, ETS-related gene; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

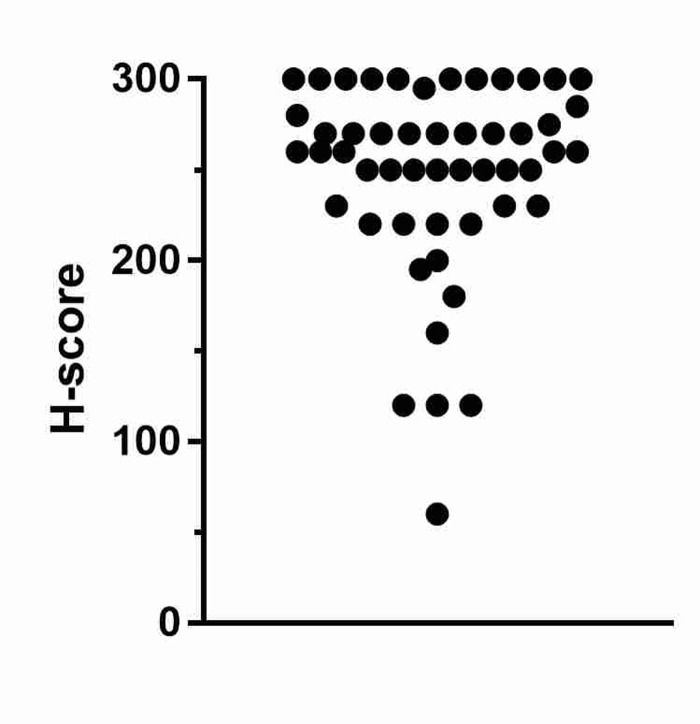

ERG expression was observed in 51 cases (34%), of which nearly all demonstrated strong ERG expression (92%) (figure 1), (intensity distribution of ERG staining shown in supplementary figure 4). No ERG expression was found in incidental benign acini within samples. ERG positivity was associated with older age, and Caucasian ethnicity (when compared with Afro-Carribean and Other ethnic groups), but not Gleason score, initial PSA level, or presence of metastatic disease at presentation (table 1).

Figure 1.

H-score distribution of ERG positive cases. 47/51 (92%) had a strongly positive H-score. ERG, ETS-related gene.

National Cancer Registry-linked oncological survival outcomes following primary androgen deprivation therapy in metastatic and non-metastatic high Gleason-grade prostate cancer

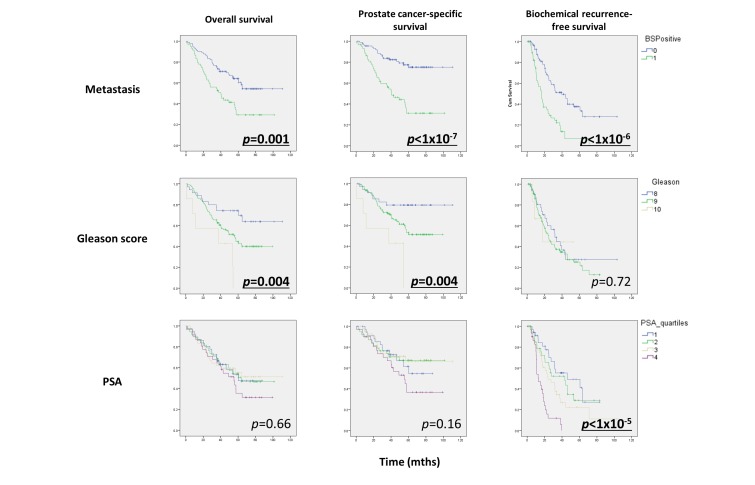

The National Cancer Registry was used to determine the vital status and death certification details for each patient. Seventy-five patients (50%) had died during follow-up, of whom 55 had died as a result of prostate cancer. Median OS for the cohort was 60.2 months. OS, CSS and BRFS for the cohort are shown (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Oncological outcomes of high-risk prostate cancer following primary androgen deprivation therapy. Significant associations shown in bold. BSPositive, bone scan positive.

Presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis significantly affected OS (p=0.001), CSS (p<1×10-7) and BRFS (p<1×10-6). Gleason score significantly affected OS (p=0.004) and CSS (p=0.004) but not BRFS (p=072). PSA at presentation only affected BRFS (p=1×10-5). Those associations were calculated using log-rank analysis.

Association of ETS-related gene expression and oncological outcomes in high risk cases treated by primary androgen deprivation therapy

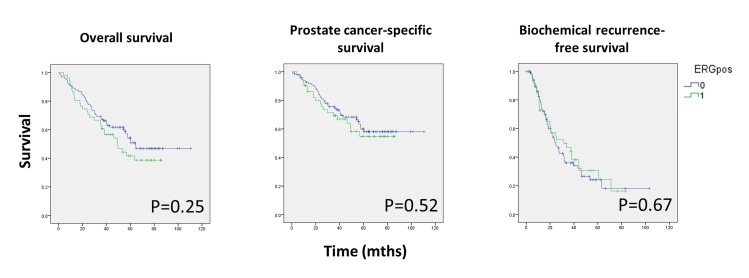

Log-rank analysis was first conducted to determine whether ERG expression predicted oncological outcomes in the high-risk cohort stratified by ERG expression status (figure 3). No statistically significant association was observed between ERG expression and OS, CSS or BRFS.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by ERG expression status for OS, CSS and BRFS.

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to determine independent predictors of oncological outcomes. Mutual adjustments were made for ERG expression, age, ethnicity, Gleason score, PSA, presence of metastasis at presentation and Charlson comorbidity (table 2). The presence of metastatic disease was significantly associated with OS (HR 2.60, 95% CI 1.54 to 4.40), CSS (HR 4.51, 95% CI 2.36 to 8.60) and BRFS (HR 3.15, 95% CI 1.93 to 5.16). Total Gleason score was significantly associated with OS (Gleason 9; HR 2.33, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.53 and Gleason 10; HR 5.81, 95% CI 2.04 to 16.52, reference group Gleason 8) and CSS (Gleason 9; HR 2.56, 95% CI 1.13 to 5.83 and Gleason 10; HR 6.45, 95% CI 2.04 to 16.52, reference group Gleason 8) but not BRFS. Age was significantly associated with OS only. We found no statistically significant association between ERG expression and OS, CSS or BRFS. The results did not change when ERG expression status was replaced with the H-score (results not shown).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis of ERG expression with other known oncological outcome parameters

| P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||

| ERG expression | 0.41 | 1.24 | 0.74 | 2.05 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 0.57 | 1.87 | 0.31 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 1.27 |

| Age | 0.02 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.19 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Caucasian (ref) | 0.75 | 0.98 | 0.44 | |||||||||

| Afro-Caribbean | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.53 | 1.53 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 1.75 | 0.52 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 1.38 |

| Other | 0.57 | 1.35 | 0.47 | 3.86 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 4.10 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 1.59 |

| Gleason score | ||||||||||||

| 8 (ref) | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.79 | |||||||||

| 9 | 0.01 | 2.33 | 1.20 | 4.53 | 0.02 | 2.56 | 1.13 | 5.83 | 0.50 | 1.20 | 0.71 | 2.01 |

| 10 | <0.001 | 5.81 | 2.04 | 16.52 | <0.01 | 6.45 | 1.92 | 21.71 | 0.73 | 1.24 | 0.35 | 4.38 |

| PSA | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Metastasis | <0.001 | 2.60 | 1.54 | 4.40 | <1×10-5 | 4.51 | 2.36 | 8.60 | <1×10-5 | 3.15 | 1.93 | 5.16 |

| Charlson comorbidity | ||||||||||||

| 0 (ref) | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.83 | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.19 | 1.52 | 0.81 | 2.87 | 0.85 | 1.08 | 0.50 | 2.35 | 0.56 | 1.18 | 0.68 | 2.07 |

| 2 | 0.06 | 1.81 | 0.97 | 3.39 | 0.67 | 1.18 | 0.56 | 2.47 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.49 | 1.67 |

| ≥3 | 0.09 | 2.00 | 0.89 | 4.47 | 0.12 | 2.17 | 0.81 | 5.84 | 0.51 | 1.29 | 0.60 | 2.75 |

Reference groups are indicated for categorical variables.

BRFS, biochemical recurrence-free survival; CSS, cancer specific survival; ERG, ETS related gene; OS, overall survival; PSA, prostate specific antigen.

Discussion

In this cohort, we examined the association of ERG expression with survival endpoints in patients treated by primary ADT. Following multivariate analysis, we found no association of ERG expression with OS, CSS or BRFS (table 2). Advances in planned adjuvant treatments for high-risk prostate cancer such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy confounds the assessment of biomarkers in patients receiving ADT in more recent cohorts. Linkage of clinical data was made with the National Cancer Registry which provided an up-to-date vital status on all patients residing in England.

ERG is commonly described as an oncogene although its ubiquitous expression in endothelial and haematopoietic stem cells suggest an essential role in angiogenesis, endothelial cell function and haematopoiesis.16 17 Since the discovery of the ERG and androgen regulated TMPRSS2 genetic fusion in prostate cancer,1 its role as a sensitive and prevalent marker for prostate cancer has been shown to be highly replicable.4 Recent whole genome sequencing studies have revealed it to be the most frequent genetic aberration in prostate cancer within the entire genome.2 Its high prevalence among all grades of disease4 18–21 however, supports its significance to be a marker of cancer per se rather than a marker for prognosis. ERG overexpression in animal models produces prostate intraepithelial neoplasia but not invasive cancer, suggesting it to be an early event in the natural history of prostate cancer.22

Androgen receptor is known to play a role in the development of castrate resistance in prostate cancer5 and its levels have been shown to correlate with ERG expression.6 To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have looked into the possible association of primary ADT on ERG positive cancer with varying conclusions.23–25 Similar to the findings of our study, Berg et al suggest no association between ERG expression and the development of castrate resistance in patients treated with primary ADT.24 Huang et al had shown that combined ERG and androgen receptor status was significant in its association with a worsened survival in prostate cancer.23 However, sole expression of ERG had not conferred worsened survival outcomes in patients with prostate cancer. Graff et al suggest a protective benefit in managing ERG positive prostate cancer with ADT.25

Our study is the largest cohort of solely high-risk cancers homogeneously treated with initial ADT as planned monotherapy with subsequent high-quality vital status determination through a national registry.

In organ confined prostate cancer, ERG expression and its association with clinical outcomes has been the subject of numerous studies with conflicting outcomes.3 26 A meta-analysis describing ERG fusion positive cancer and its associated outcomes in postprostatectomy showed ERG fusion events to be associated with a higher clinical stage at diagnosis of T3 over T2 with a risk ratio of 1.23, yet no association was found for cancer specific survival or disease recurrence.4

Although we used IHC to estimate TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion status, studies have shown very high concordance between more accurate fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques.27–30 The reproducibility of the technique was assessed using an additional antibody clone, as well as determining technical success for each sample using endothelial cell expression as internal controls (supplementary figures 1 and 3). The prevalence (34%) of ERG expression is in line with previous studies.4 The association between Caucasian ethnicity and ERG expression agrees with a previous study evaluating TMPRSS2:ERG fusion events.31 Higher age was significantly associated with ERG expression in our cohort (p=0.03), in contrast to other studies that showed a higher proportional expression in the younger men32 or no correlation at all.4 14 It is possible that this is an association seen only in high grade prostate cancer cases.

Limitations

The retrospective nature of the study had resulted in a reduction in the collection of other covariates such as stage at diagnosis.4

Moreover, a subset of patients within the cohort received unplanned adjuvant therapy in addition to androgen deprivation monotherapy which may have influenced the OS. This was not assessed as a covariate due to the heterogeneous nature of the treatment and small patient numbers.

Patients who did not have a complete dataset were excluded from the study although this had represented a small proportion of patients (20/169). In addition, despite being the largest cohort of patients solely treated with primary ADT, the sample size remains small reducing the power of this study population.

Both quantitative33 and qualitative differences in the ERG mutation have been implicated in prognostication of prostate cancer. Patients with cancer cells exhibiting an aberration consisting of both a duplication and deletion of the 5’ end of ERG (known as 2+ ‘Edel’) were predisposed to a poorer disease specific survival.34 35 In this context, the use of IHC was a limitation as it cannot detect the genomic fusion quantitatively or qualitatively but only isolated expression of the ERG protein.7 27 It is important to note that the H score does not provide a quantitative measurement of the ERG aberration.27 With this knowledge at hand, subclassifications of ERG mutations when assessing prognostic indicators is recommended in future clinical studies. IHC may be controversial as a detection method of the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene. Sung JY et al expressed caution to its use for its false positive rate36while Gsponer and colleagues identified a subgroup of ERG genetic alterations that are undetectable at a protein level.37

Conclusion

While ERG expression is known to be strongly associated with oncogenesis, we show that ERG expression did not predict oncological survival in prostate cancer patients treated with ADT. Our findings are in line with other studies showing a lack of association between ERG expression and prostate cancer treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HY led the study design, analysed data and was involved in revision, drafting and approval of the final manuscript. MR was involved in sample and data collection, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. AC and DA were both involved in analysis of the prostate cancer tissue. HM, MY and PD provided critical review of the study design and manuscript. All authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional approval was granted prior to the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Due to the confidential nature of our data which may identify individuals, even following anonymisation, we have chosen not to make our data publicly available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science 2005;310:644–8. 10.1126/science.1117679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fraser M, Sabelnykova VY, Yamaguchi TN, et al. Genomic hallmarks of localized, non-indolent prostate cancer. Nature 2017;541:359–64. 10.1038/nature20788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sreenath TL, Dobi A, Petrovics G, et al. Oncogenic activation of ERG: A predominant mechanism in prostate cancer. J Carcinog 2011;10:37 10.4103/1477-3163.91122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pettersson A, Graff RE, Bauer SR, et al. The TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangement, ERG expression, and prostate cancer outcomes: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:1497–509. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clinckemalie L, Spans L, Dubois V, et al. Androgen regulation of the TMPRSS2 gene and the effect of a SNP in an androgen response element. Mol Endocrinol 2013;27:2028–40. 10.1210/me.2013-1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu J, Yu J, Mani RS, et al. An integrated network of androgen receptor, polycomb, and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 2010;17:443–54. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Attard G, Swennenhuis JF, Olmos D, et al. Characterization of ERG, AR and PTEN gene status in circulating tumor cells from patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2009;69:2912–8. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scheble VJ, Scharf G, Braun M, et al. ERG rearrangement in local recurrences compared to distant metastases of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Virchows Arch 2012;461:157–62. 10.1007/s00428-012-1270-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perner S, Svensson MA, Hossain RR, et al. ERG rearrangement metastasis patterns in locally advanced prostate cancer. Urology 2010;75:762–7. 10.1016/j.urology.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, et al. An electronic application for rapidly calculating Charlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer 2004;4:94 10.1186/1471-2407-4-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NCRAS. The National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/national-cancer-registration-and-analysis-service-ncras (Cited 10 November 2015).

- 12. Office of National Statistics. Guidance for doctors completing Medical Certificates of Cause of Death in England and Wales. 2010. http://www.gro.gov.uk/images/medcert_july_2010.pdf (Cited 15 Nov 2015).

- 13. Roach M, Hanks G, Thames H, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: Recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:965–74. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoogland AM, Jenster G, van Weerden WM, et al. ERG immunohistochemistry is not predictive for PSA recurrence, local recurrence or overall survival after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Mod Pathol 2012;25:471–9. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kraus JA, Dabbs DJ, Beriwal S, et al. Semi-quantitative immunohistochemical assay versus oncotype DX(®) qRT-PCR assay for estrogen and progesterone receptors: an independent quality assurance study. Mod Pathol 2012;25:869–76. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wagner W, Ansorge A, Wirkner U, et al. Molecular evidence for stem cell function of the slow-dividing fraction among human hematopoietic progenitor cells by genome-wide analysis. Blood 2004;104:675–86. 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Birdsey GM, Dryden NH, Amsellem V, et al. Transcription factor Erg regulates angiogenesis and endothelial apoptosis through VE-cadherin. Blood 2008;111:3498–506. 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Shen R, et al. Comprehensive assessment of TMPRSS2 and ETS family gene aberrations in clinically localized prostate cancer. Mod Pathol 2007;20:538–44. 10.1038/modpathol.3800769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Font-Tello A, Juanpere N, de Muga S, et al. Association of ERG and TMPRSS2-ERG with grade, stage, and prognosis of prostate cancer is dependent on their expression levels. Prostate 2015;75:1216–26. 10.1002/pros.23004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bismar TA, Dolph M, Teng LH, et al. ERG protein expression reflects hormonal treatment response and is associated with Gleason score and prostate cancer specific mortality. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:538–46. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leinonen KA, Saramäki OR, Furusato B, et al. Loss of PTEN is associated with aggressive behavior in ERG-positive prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013;22:2333–44. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0333-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tomlins SA, Laxman B, Varambally S, et al. Role of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Neoplasia 2008;10:177–IN9. 10.1593/neo.07822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang KC, Alshalalfa M, Hegazy SA, et al. The prognostic significance of combined ERG and androgen receptor expression in patients with prostate cancer managed by androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer Biol Ther 2014;15:1120–8. 10.4161/cbt.29689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berg KD, Røder MA, Thomsen FB, et al. The predictive value of ERG protein expression for development of castration-resistant prostate cancer in hormone-naïve advanced prostate cancer treated with primary androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate 2015;75:1499–509. 10.1002/pros.23026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graff RE, Pettersson A, Lis RT, et al. The TMPRSS2:ERG fusion and response to androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Prostate 2015;75:897–906. 10.1002/pros.22973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adamo P, Ladomery MR. The oncogene ERG: a key factor in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2016;35:403–414. 10.1038/onc.2015.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaux A, Albadine R, Toubaji A, et al. Immunohistochemistry for ERG expression as a surrogate for TMPRSS2-ERG fusion detection in prostatic adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1014–20. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821e8761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schelling LA, Williamson SR, Zhang S, et al. Frequent TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangement in prostatic small cell carcinoma detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization: the superiority of fluorescence in situ hybridization over ERG immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol 2013;44:2227–33. 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Falzarano SM, Zhou M, Carver P, et al. ERG gene rearrangement status in prostate cancer detected by immunohistochemistry. Virchows Arch 2011;459:441–7. 10.1007/s00428-011-1128-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park K, Tomlins SA, Mudaliar KM, et al. Antibody-based detection of ERG rearrangement-positive prostate cancer. Neoplasia 2010;12:590–8. 10.1593/neo.10726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Magi-Galluzzi C, Tsusuki T, Elson P, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prevalence and class are significantly different in prostate cancer of Caucasian, African-American and Japanese patients. Prostate 2011;71:489–97. 10.1002/pros.21265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schaefer G, Mosquera JM, Ramoner R, et al. Distinct ERG rearrangement prevalence in prostate cancer: higher frequency in young age and in low PSA prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2013;16:132–8. 10.1038/pcan.2013.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. FitzGerald LM, Agalliu I, Johnson K, et al. Association of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion with clinical characteristics and outcomes: results from a population-based study of prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2008;8:1 10.1186/1471-2407-8-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Attard G, Clark J, Ambroisine L, et al. Duplication of the fusion of TMPRSS2 to ERG sequences identifies fatal human prostate cancer. Oncogene 2008;27:253–63. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Yu J, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2-ETS gene aberrations in androgen-independent metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2008;68:3584–90. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sung JY, Jeon HG, Jeong BC, et al. Correlation of ERG immunohistochemistry with molecular detection of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. J Clin Pathol 2016;69:586–92. 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gsponer JR, Braun M, Scheble VJ, et al. ERG rearrangement and protein expression in the progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2014;17:126–31. 10.1038/pcan.2013.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025161supp001.pdf (918.8KB, pdf)