Abstract

Objectives

Research has shown that people with physical impairment report lower utilisation of preventive services. The aim of this study was to examine whether women with mobility impairments have lower odds of using mammography compared with women with no such impairment, and explore the factors that are associated with lower utilisation.

Sample and design

We performed secondary analysis, using logistic regressions, of deidentified cross-sectional data from the European Health Interview Survey, Wave 2. The sample included 9491 women from across the UK, 2697 of whom had mobility impairment. The survey method involved face-to-face and telephone interviews.

Outcome measures

Self-report of the last time a mammogram was undertaken.

Results

Adjusting for various demographic and socioeconomic variables, women with mobility impairment had 1.3 times (95% CI 0.70 to 0.92) lower odds of having a mammogram than women without mobility impairment. Concerning women with mobility impairment, married women had more than twice the odds of having a mammogram than women that had never been married (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.88). Women in Scotland had 1.5 times (95% CI 1.08 to 2.10) higher odds of undertaking the test than women in England. Women with upper secondary education had 1.4 times (95% CI 1.10 to 1.67) higher odds of undergoing the test than women with primary or lower secondary education. Also, women from higher quintiles (third and fifth quintiles) had higher odds of using mammography, with the women in the fifth quintile having 1.5 times (95% CI 1.02 to 2.15) higher odds than women from the first quintile.

Conclusions

In order to achieve equitable access to mammography for all women, it is important to acknowledge the barriers that impede women with mobility impairment from using the service. These barriers can refer to structural disadvantage, such as lower income and employment rate, transportation barriers, or previous negative experiences, among others.

Keywords: women with mobility impairment, mammography, preventive services, cancer screening, United Kingdom

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is based on a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling women.

We use various demographic and socioeconomic variables to investigate the association between these factors and mammography for women with mobility impairment in the UK.

Outcome measures were self-reported, which might have introduced response bias.

We cannot establish any causal links, due to the study’s cross-sectional design.

Introduction

Research has shown that people with physical impairment generally report worse access and utilisation of healthcare services, including preventive and screening services.1–5 Several studies have evidenced how access to some cancer screening services can be compromised due to the presence of pre-existing physical impairment.6–11 A recent study in the UK showed that disabled women—including women with physical limitations—report worse access to healthcare compared with any other group, perhaps illustrating how gender and disability intersect to create structural disadvantage for disabled women.3

There are several reasons that have been associated with lower utilisation of healthcare services by disabled people, and for women in particular. These include, among other reasons, inaccessible healthcare facilities and/or equipment, lack of appropriate parking, lack of social support, and financial constraints, and the intersection of all these factors with gender-based structural disadvantage.1 5 8 There are also several intangible barriers that negatively affect utilisation of healthcare services by disabled women; past negative experiences with healthcare professionals, being treated as low-priority patients, not being adequately informed, or having their impairments ignored, are some of the reasons women give for the low utilisation of services, including mammography.5 6

Mammography is an important screening tool for breast cancer.12 In well-resourced settings, which include most high-income countries, WHO’s position paper on mammography recommends population-based screening every 2 years for all women aged 50–69 years.12 Several countries, including the US, Norway, Denmark, and the UK, implement such national screening programmes.13–17 A Cochrane systematic review showed that the benefits of mortality decrease might be outweighed by overdiagnosis rates and higher rates of aggressive treatment, both of which were attributed to mammography.18 However, there is strong evidence showing that population-wide screening could lead to an increase of early-cancer diagnosis, with a concomitant decrease of late-stage diagnosis, hence leading to a mortality decrease.12 19

In the UK, women between the ages of 50 and 70 are invited to undertake a mammogram every 3 years, as part of a national screening programme by the National Health Service (NHS).20 While there are data available regarding women in England,21 little is known regarding mammography utilisation by women with physical impairment across the UK; it is not known whether there is a difference in the utilisation rates between women with and without any mobility impairment, nor which are some of the factors associated with these utilisation rates.

Most of the existing evidence suggests that disabled women have lower utilisation rates and worse access to mammography compared with non-disabled women.8 10 22–25 Transportation, quality of the experience and lack of appropriate information, are among the reasons given for this.6 26 Several of these studies are small-scale studies, which although they give important insights into the experiences of women as they navigate the healthcare system; they do not allow any conclusions regarding utilisation of preventive services at a population level. A recent large prospective study showed that disabled women in England have lower odds of having a mammogram compared with non-disabled women.21

In this article, we examine the utilisation of mammography by women with a lower limb mobility impairment in the UK. We use this term to refer to women who report difficulty or inability to walk or climb stairs, as per the available data from the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS, Wave 2). Our aim is to examine whether women with a lower limb mobility impairment have lower odds of using mammography compared with women with no such impairment, and explore the factors that are associated with lower utilisation.

This study seeks to add to the current body of evidence regarding utilisation of mammography by disabled women, by producing population-level evidence, and examining the association of a variety of demographic and socioeconomic factors—such as low income or lack of social support—with utilisation of mammography. This knowledge can inform policy and lead to the design of comprehensive support systems and target interventions that would enable real access to services, addressing the availability of services and their utilisation.

Methodology

Survey

We performed secondary analysis, using logistic regressions, of deidentified cross-sectional data from the EHIS, Wave 2. The EHIS collects health data of representative samples of population across European Union member states, providing thus the possibility to compare health indicators between countries. It is administered every 5 years.27

The survey consists of four modules: (1) demographic and socioeconomic variables, such as age, sex, marital status, employment, education, and so on; (2) variables on health status, for example, self-perceived general health, chronic conditions, accidents, functional limitations in daily activities, and so on; (3) variables on healthcare use, such as consultations, unmet healthcare needs, preventive services, and so on; and (4) health determinants, for instance, weight, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise, social support, and so on.28 The survey analyses 21 areas of health concerns and health-related behaviours, and 81 specific item questions. All measures are self-reported.29 For more information on the EHIS questionnaire, refer to the survey website.27 28

The UK did not participate in the first EHIS wave (2006–2009), but it did take part in the second wave. Data were collected for residents in private households, over 16 years of age, residing in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. For Great Britain, data were collected between April 2013 and March 2014 by the Office for National Statistics. Data for Northern Ireland were collected between April and September 2014 by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. In Great Britain, the survey was conducted as a follow-up to the Labour Force Survey; individuals who did not object in their final wave of contact, in the sampled households, completed the EHIS Wave 2 questionnaire. In Northern Ireland, a simple random sample of households on the Land and Property Services Agency property gazetteer was used. In total, the UK survey included 20 161 observations, a sample size which was much higher than the estimated minimum effective size for the country, which was 13 085.30

The interviews involved both face-to-face (20%) and telephone interviews (80%). For the face-to-face interviews, the interviewers conducted computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) using laptops at the address of the respondents, while for the telephone interviews, computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) were conducted. The CAPI and CATI questionnaires were generally similar, with only minor changes to account for the different mode of interviewing.30

The microdata did not contain any personal information, such as names or addresses, which would allow direct identification. In order to ensure confidentiality, a set of anonymisation rules was applied.31 Access to microdata is granted only for scientific purposes; we were granted access by the UK Data Service (www.ukdataservice.ac.uk).

Data and variables

There are two questions in the EHIS that measure mobile difficulty: (1) variable PL6, ‘Difficulty in walking half a km on level ground without the use of any aid’, and (2) variable PL7, ‘Difficulty in walking up or down 12 steps’. These two variables were merged into a new variable, called ‘mobility impairment’, with answers ‘without difficulty’ (women that answered that they had no difficulty in performing either tasks), and ‘with difficulty’ (women that replied that they had some difficulty in performing or were unable to do at least one of the tasks).

Our dependent variable, ‘up to date with mammography’, was recoded and was binary, that is, ‘Yes’ (included the answers ‘within the last 12 months’, ‘1 to less than 2 years’, and ‘2 to less than 3 years’) and ‘No’ (‘more than 3 years’ and ‘never’). This recoding was done according to the NHS guidelines on mammography.26 Previous research has also employed this variable, looking at women being up to date with mammography.10

In total, we had 9995 observations for women that answered the question on mammography. Since STATA, by default, performs listwise deletion and displays calculations that have non-missing values on all variables listed, our total sample size was 9491 observations (6794 observations for women without mobility impairment, and 2697 for women with mobility impairment). Since only a very small percentage of observations was deleted, we decided not to proceed to maximum likelihood or multiple imputation.32 The sample is representative of the target population (test results available on request).

The control variables included the following: (1) age: 20–49/50–69/70+ (while the target group is 50–69 years old women, the survey showed that almost 30% of women outside the target group have undertaken a mammogram); (2) civil status: never married/married/widowed/divorced; (3) region: England/Wales/ Scotland/Northern Ireland; (4) urbanisation: thinly populated area/moderate populated area/densely populated area; (5) education: primary and lower secondary/upper secondary/post secondary and tertiary, short/tertiary; (6) income quintiles (net monthly equivalised household income): first quintile/second quintile/third quintile/fourth quintile/fifth quintile; (7) employment: unemployed/employed/ inactive; (8) health self-assessment: bad (answers ‘bad’ and ‘very bad’)/fair (answer ‘fair’)/good (answers ‘good’ and ‘very good’); and (9) help from neighbours (how easy it is to get help from neighbours in case of need): difficult/possible/ easy.

All analyses were performed using STATA/MP V.14.2.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the design or conduct of this study. However, the research aim was informed by patients’ priorities, and experiences, as these were communicated through patient and public involvement in a previous study (the Challenges of Cancer and Disability Study, Tenovus TIG2017-05).

Results

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the study sample.

Table 1.

Comparison between women with and without mobility impairment

| Parameter | Women without mobility impairment (n=6794) |

Women with mobility impairment (n=2697) |

P value, χ2 test | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age groups | |||||

| 20–49 (n=3270) | 2919 | 43.0 | 351 | 13.0 | P<0.0001 |

| 50–69 (n=3971) | 2839 | 42.8 | 1132 | 42.0 | |

| 70+ (n=2250) | 1036 | 15.3 | 1214 | 45.1 | |

| Civil status | |||||

| Never married (n=1515) | 1259 | 18.5 | 256 | 9.5 | P<0.0001 |

| Married (n=5386) | 4097 | 60.3 | 1289 | 47.8 | |

| Widowed (n=1324) | 604 | 8.9 | 720 | 26.7 | |

| Divorced (n=1266) | 834 | 12.3 | 432 | 16.0 | |

| Region | |||||

| England (n=7895) | 5695 | 83.8 | 2200 | 81.6 | P<0.0001 |

| Wales (n=421) | 269 | 4.0 | 152 | 5.6 | |

| Scotland (n=822) | 596 | 8.8 | 226 | 8.4 | |

| Northern Ireland (n=353) | 234 | 3.4 | 119 | 4.4 | |

| Urbanisation | |||||

| Thinly populated are (n=1322) | 945 | 13.9 | 377 | 14.0 | P=0.992 |

| Moderate-populated area (n=2575) | 1842 | 27.1 | 733 | 27.2 | |

| Densely populated area (n=5594) | 4007 | 59.0 | 1587 | 58.8 | |

| Education | |||||

| Primary/lower secondary (n=3040) | 1699 | 25.0 | 1341 | 49.7 | P<0.0001 |

| Upper secondary (n=3223) | 2394 | 35.2 | 829 | 30.7 | |

| Post secondary/tertiary, short (n=1495) | 1156 | 17.0 | 339 | 12.6 | |

| Tertiary (n=1733) | 1545 | 22.7 | 188 | 7.0 | |

| Income quintiles | |||||

| First quintile (n=1962) | 1108 | 16.3 | 854 | 31.7 | P<0.0001 |

| Second quintile (n=2008) | 1336 | 19.7 | 672 | 24.9 | |

| Third quintile (n=1932) | 1352 | 19.9 | 580 | 21.5 | |

| Fourth quintile (n=1852) | 1493 | 22.0 | 359 | 13.3 | |

| Fifth quintile (n=1737) | 1505 | 22.2 | 232 | 8.6 | |

| Employment | |||||

| Unemployed (n=360) | 271 | 4.0 | 89 | 3.3 | P<0.0001 |

| Employed (n=4304) | 3836 | 56.5 | 468 | 17.4 | |

| Inactive (n=4827) | 2687 | 39.6 | 2140 | 79.4 | |

| Health self-assessment | |||||

| Bad (n=797) | 90 | 1.3 | 707 | 26.2 | P<0.0001 |

| Fair (n=1896) | 774 | 11.4 | 1122 | 41.6 | |

| Good (n=6798) | 5930 | 87.3 | 868 | 32.2 | |

| Help from neighbours | |||||

| Difficult (n=1312) | 805 | 11.9 | 507 | 18.8 | P<0.0001 |

| Possible (n=1923) | 1426 | 21.0 | 497 | 18.4 | |

| Easy (n=6256) | 4563 | 67.2 | 1693 | 62.8 | |

For more information on the variables, see the European Health Interview Survey Wave 2 methodological manual.28

Some of the points presented in table 1 are of particular interest. First, concerning education, about half of women with mobility impairment had only primary or lower secondary education, as opposed to only a quarter of women without any mobility impairment; a much higher percentage of women from the latter group had also attended tertiary education. Second, more women with mobility impairment (32%) belonged to the first income quintile than women with no mobility impairment (16%). Less than 9% of women from the former group belonged to the richest segment; this percentage was more than 22% for women without any mobility impairment. Third, the percentage of women with mobility impairment that were inactive was double (ie, almost 80%) than that of women without any mobility problems. All these points underline the structural disadvantage faced by women with mobility impairment in the UK: lower education and lower income, coupled with a much higher likelihood of being inactive in terms of employment.

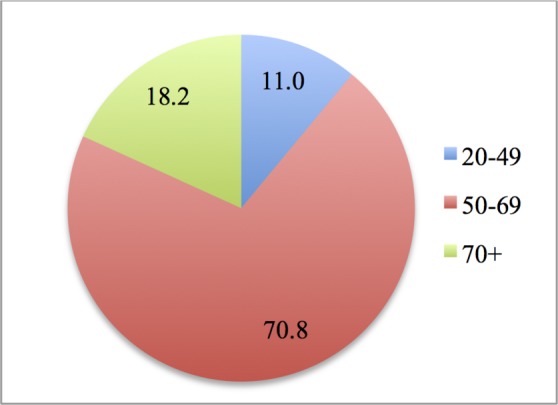

Figure 1 shows the percentage of women (total sample, including both women with and without mobility impairment) that have undertaken mammography, by age group.

Figure 1.

Women having undertaken mammography, by age group (%). Note: 4433 women in total.

As it can be seen in figure 1, 71% of all women who undertook mammography were in the target group, that is, 50–69 years of age. Almost 30% of all women that underwent the test were outside the target group. In certain parts of England, women younger than 50 and older than 70 years are invited for mammograms,33 while a systematic review has shown that women out of the target group also undergo mammography.18

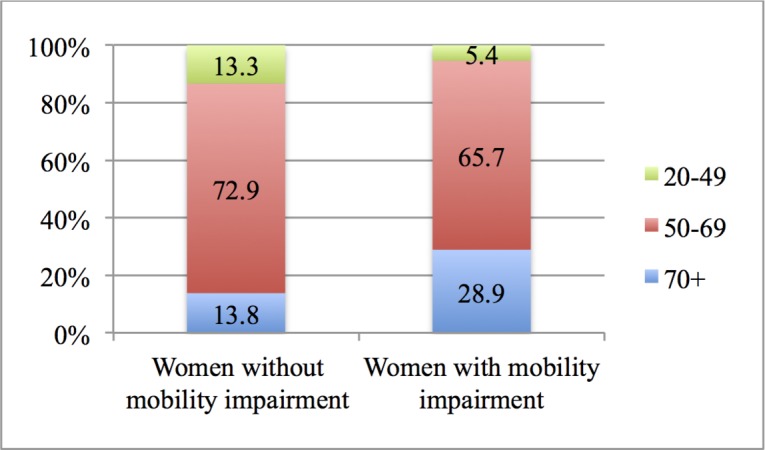

Figure 2 shows women with and without mobility impairments that have undertaken mammography, by age group.

Figure 2.

Women with and without mobility impairment having undertaken mammography, by age group (%). Note 1: 3145 women without mobility impairment and 1288 women with mobility impairment. Note 2: differences are statistically significant.

Figure 2 shows that almost 30% of women with mobility impairment that undertook mammography were 70+years old, that is, outside the target group; this percentage is less than half of that for women without mobility impairment.

We performed logistic regressions to see whether there was any difference in utilisation rates of mammography between women with and without mobility impairment in the UK, and to investigate the factors associated with such rates. The first logistic regression—which included all the variables of table 1—showed that women with mobility impairment had 1.3 times lower odds of undertaking a mammogram than women without mobility problems (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.92, P=0.002) (full results not presented here but available on request).

Next, table 2 presents possible factors associated with having a mammogram for women with mobility impairment in the UK. Model (1) presents age-adjusted ORs. Model (2) incorporates other demographic and socioeconomic variables, while Model (3) presents the fully adjusted ORs (includes all variables of table 1).

Table 2.

Factors associated with utilisation rates of mammography by women with mobility impairment in the UK

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age groups (20–49 as reference) | ||||||

| 50 – 69 | 11.57*** | 8.67 to 15.44 | 11.99*** | 8.78 to 16.38 | 12.12*** | 8.85 to 16.61 |

| 70+ | 1.69*** | 1.27 to 2.25 | 1.96*** | 1.39 to 2.75 | 1.94*** | 1.37 to 2.74 |

| Civil status (never married as reference) | ||||||

| Married | 2.05*** | 1.48 to 2.85 | 2.07*** | 1.49 to 2.88 | ||

| Widowed | 0.934 | 0.65 to 1.34 | 0.95 | 0.66 to 1.37 | ||

| Divorced | 1.44 | 1.00 to 2.08 | 1.46* | 1.01 to 2.12 | ||

| Regions (England as reference) | ||||||

| Wales | 1.00 | 0.68 to 1.48 | 1.01 | 0.68 to 1.49 | ||

| Scotland | 1.48* | 1.06 to 2.05 | 1.51* | 1.08 to 2.10 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 0.91 | 0.58 to 1.41 | 0.90 | 0.57 to 1.40 | ||

| Urbanisation (thinly populated as reference) | ||||||

| Intermediate-populated area | 0.89 | 0.67 to 1.19 | 0.90 | 0.67 to 1.20 | ||

| Densely populated area | 0.77 | 0.59 to 1.01 | 0.77 | 0.59 to 1.01 | ||

| Education (primary/lower secondary as reference) | ||||||

| Upper secondary | 1.33** | 1.08 to 1.64 | 1.36** | 1.10 to 1.67 | ||

| Post secondary and tertiary, short | 1.20 | 0.91 to 1.58 | 1.21 | 0.91 to 1.60 | ||

| Tertiary | 0.88 | 0.61 to 1.28 | 0.88 | 0.60 to 1.28 | ||

| Employment (unemployed as reference) | ||||||

| Employed | 0.94 | 0.54 to 1.66 | 0.93 | 0.53 to 1.63 | ||

| Inactive | 1.29 | 0.76 to 2.20 | 1.30 | 0.76 to 2.22 | ||

| Income (first quintile as reference) | ||||||

| Second quintile | 1.11 | 0.88 to 1.40 | 1.09 | 0.86 to 1.38 | ||

| Third quintile | 1.32* | 1.03 to 1.69 | 1.29** | 1.01 to 1.66 | ||

| Fourth quintile | 1.18 | 0.87 to 1.59 | 1.18 | 0.87 to 1.60 | ||

| Fifth quintile | 1.46* | 1.01 to 2.11 | 1.49** | 1.02 to 2.15 | ||

| Health self-assessment (bad as reference) | ||||||

| Fair | 1.14 | 0.91 to 1.42 | ||||

| Good | 1.11 | 0.87 to 1.42 | ||||

| Support from neighbours (difficult as reference) | ||||||

| Possible | 1.08 | 0.81 to 1.45 | ||||

| Easy | 1.07 | 0.85 to 1.35 | ||||

| Observations | 2790 | 2738 | 2697 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1636 | 0.1908 | 0.1923 | |||

| χ2 (21) | 631.29 | 722.80 | 718.04 | |||

| Prob>χ2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||

| McFadden R2 | 0.162 | 0.179 | 0.180 | |||

| Deviance | 3228.188 | 3066.311 | 3015.368 | |||

| AIC | 3234.188 | 3106.311 | 3063.368 | |||

| BIC | 3251.989 | 3224.610 | 3204.965 | |||

*P < 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001.

AIC, akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

Due to a higher McFadden R2, and lower deviance, and AIC and BIC values, Model (3) provided a better fit than the previous two models. There was no collinearity affecting the results, with mean variance inflation factor of 2.21.

As it can be seen in table 2, the target group for having a mammogram (ie, the 50–69 group) was the one with the highest odds of undertaking it: women in this age subgroup had 12 times higher odds of having this screening than women in the 20–49 subgroup. Regarding civil status, married women had more than twice the odds of having a mammogram than women that had never been married; divorced women had 1.5 times higher odds. Women with mobility impairment in Scotland had 1.5 times higher odds of having the mammogram than women in England. Women with upper secondary education had 1.4 times higher odds to have a mammogram than women with primary or lower secondary education. Also, women from higher income quintiles (third and fifth quintiles) had higher odds of undertaking the mammogram, with the women in the fifth quintile having 1.5 times higher odds than women from the first quintile.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether women with mobility impairment in the UK were less likely to be up to date with mammography compared with women with no mobility impairment, and explored some of the factors associated with lower utilisation. The results showed a statistically significant difference between women with and without mobility impairment, with women with mobility impairment having 1.3 times lower odds of undertaking a mammogram than women without mobility impairment. Furthermore, the results showed a positive association between married civil status, high income, educational attainment and living in Scotland, and being up to date with mammography.

One of the strengths of the study is that it is based on data from a nationally representative sample. It also adds to the body of literature by examining the association of several factors with mammography utilisation for women with mobility impairment, an issue that has been generally little explored, particularly in the UK.

One of the limitations of the study is that while we established associations between various factors and utilisation of mammography by women with mobility impairment, we cannot infer causality due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Another limitation of the study is that there is no information in the EHIS on the reasons that influence utilisation of mammography. Furthermore, the EHIS relies on self-reporting information, which leaves the instrument open to response bias; however, there is no relevant information on this aspect. Another limitation of the study is the way mobility impairment was defined, which potentially included women with only short-term impairment, together with women with longer term impairment; this might have had an impact on external validity.

The findings showed that women with mobility impairment had 1.3 lower odds of being up to date with mammography. This is consistent with previous research that shows that in the UK, there are long-standing inequalities between people’s cancer experiences.34 This finding is also consistent with research findings from a study in England.25 Bone et al performed an analysis of data from the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey.35 They analysed data from 71 793 patients with cancer and found evidence that patients with cancer with long-standing conditions in England, including people with physical conditions and disabilities, reported poorer care. These inequalities persisted even when controlling for other factors. Further to this, people with pre-existing disability diagnosed with cancer report low satisfaction and use of services.7 8 36 As Liu and Clark have shown, quality of the experience matters37; previous negative experiences with mammography might deter women with physical impairments from undertaking the test in the future.

The findings also showed that married women had higher odds of having a mammogram than women that had never been married. This result is in accordance with evidence demonstrating the protective role of married civil status.23 38 Indeed, married people tend to have more fixed residence, regular doctors, and fixed healthcare places, and therefore are more likely to be informed and accept preventive health services than unmarried people.38 They have also a stronger social network (for example, family members, relatives, and friends) that can offer them more emotional and practical support (for instance, transportation) to attend such screenings, as well as help them adopt healthier behaviours.

Our study also revealed that there are differences in the utilisation rates of mammography between women living in different regions in the UK, with women with mobility impairment living in Scotland having higher odds of undertaking the test than women in England. The reason behind this might be the usage of mobile screening units in Scotland, which appears to enable access to mammography for underserved populations.39

Furthermore, our study showed that women with mobility impairments with higher education had higher odds of having a mammogram than women with primary or lower secondary education. Women with mobility impairment that belonged to higher income quintiles had also higher odds of having a mammogram than women belonging to the first quintile. This result agrees with previous research that found that disabled women with higher education and an overall higher socioeconomic status were more likely to undertake preventive examinations.40 41 Educational attainment beyond upper secondary did not seem to have any further positive effect on the update of mammography.

These inequalities in the experiences of patients with cancer in the UK conflict with several of the recommendations of recent strategic documents, including ‘Achieving world-class cancer outcomes: a Strategy for England 2015–2020’ and the Cancer Delivery Plan for Wales.42 43 Both documents call for access to equitable care, achieving the best experience, and promoting delivery of cancer care responsive to individual needs.

Overall, taking into account the global demographic, epidemiological and socioeconomic changes—including ageing, urbanisation, reduction in morbidity and mortality rates, and increase in chronic diseases— it is essential that preventive health services are better promoted and reach all people, especially disadvantaged groups, such as disabled people, women and the poor. WHO position paper on mammography states that:

Population-based screening programmes identify and individually invite each person in the eligible population to attend each round of screening so that each person in the eligible population has an equal chance of benefiting from screening. (p. 23).12

This statement, however, overlooks the fact that not everyone has an equal chance of benefitting from screening; people with mobility impairment may, for example, face transportation barriers, which could stop them from accessing screening services, despite their availability. Women with mobility impairment, and disabilities in general, are further disadvantaged, as they also face structural disadvantage—in the form of lower education, lower income and greater poverty—than men, as shown in this study and supported by a body of existing research.44 45 In order to enhance the utilisation of mammography (and possibly the use of other preventive services), it is important to acknowledge the barriers that stop women from using the service and adopt measures that would lead to a more equitable utilisation. The wide adoption of mobile screening units might be a way to improve access for this population. This needs to be complemented by increased disability awareness for healthcare professionals, making them sensitive to addressing impairment-specific needs in order to achieve inclusive services for all.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Gill Tyrer for her contribution as a patient and public representative in a previous project (Tenovus, TIG2017-05), which offered the stimulus to explore barriers to cancer screening for this population.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors jointly conceived the final research question and aims and objectives, reviewed the literature, produced the analysis plan and carried out the analysis, and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix and dataset available from the UK Data Service upon request. https://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/catalogue/?sn=7881.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, et al. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J Public Health 2000;90:955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kroll T, Jones GC, Kehn M, et al. Barriers and strategies affecting the utilisation of primary preventive services for people with physical disabilities: a qualitative inquiry. Health Soc Care Community 2006;14:284–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakellariou D, Rotarou ES. Access to healthcare for men and women with disabilities in the UK: secondary analysis of cross-sectional data. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016614 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Popplewell NT, Rechel BP, Abel GA. How do adults with physical disability experience primary care? A nationwide cross-sectional survey of access among patients in England. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004714 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibson J, O’Connor R. Access to health care for disabled people: a systematic review. Social Care and Neurodisability 2010;1:21–31. 10.5042/scn.2010.0599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llewellyn G, Balandin S, Poulos A, et al. Disability and mammography screening: intangible barriers to participation. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33(19-20):1755–67. 10.3109/09638288.2010.546935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Angus J, Seto L, Barry N, et al. Access to cancer screening for women with mobility disabilities. J Cancer Educ 2012;27:75–82. 10.1007/s13187-011-0273-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peters K, Cotton A. Barriers to breast cancer screening in Australia: experiences of women with physical disabilities. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:563–72. 10.1111/jocn.12696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Devaney J, Seto L, Barry N, et al. Navigating healthcare: gateways to cancer screening. Disabil Soc 2009;24:739–51. 10.1080/09687590903160233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horner-Johnson W, Dobbertin K, Andresen EM, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities associated with disability severity. Womens Health Issues 2014;24:e147–53. 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, et al. Use of screening and preventive services among women with disabilities. Am J Med Qual 2001;16:135–44. 10.1177/106286060101600405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. WHO Position Paper On Mammography Screening. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weedon-Fekjær H, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ. Modern mammography screening and breast cancer mortality: population study. BMJ 2014;348:g3701 10.1136/bmj.g3701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1998–2005. 10.1056/NEJMoa1206809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Broeders M, Moss S, Nyström L, et al. The impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality in Europe: a review of observational studies. J Med Screen 2012;19(1_suppl):14–25. 10.1258/jms.2012.012078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jørgensen KJ, Zahl PH, Gøtzsche PC. Breast cancer mortality in organised mammography screening in Denmark: comparative study. BMJ 2010;340:c1241 10.1136/bmj.c1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rafia R, Brennan A, Madan J, et al. Modeling the Cost-Effectiveness of Alternative Upper Age Limits for Breast Cancer Screening in England and Wales. Value Health 2016;19:404–12. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD001877 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, et al. Efficacy of screening mammography. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1995;273:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Health Service. Breast cancer screening. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/breast-cancer-screening/ (accessed 29 May 2018).

- 21. Floud S, Barnes I, Verfürden M, et al. Disability and participation in breast and bowel cancer screening in England: a large prospective study. Br J Cancer 2017;117:1711–4. 10.1038/bjc.2017.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Todd A, Stuifbergen A. Breast cancer screening barriers and disability. Rehabil Nurs 2012;37:74–9. 10.1002/RNJ.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iezzoni LI, Kilbridge K, Park ER. Physical access barriers to care for diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women with mobility impairments. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:711–7. 10.1188/10.ONF.711-717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iezzoni LI, Park ER, Kilbridge KL. Implications of mobility impairment on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. J Womens Health 2011;20:45–52. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sakellariou D, Rotarou ES. Utilisation of cancer screening services by disabled women in Chile. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176270 10.1371/journal.pone.0176270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barr JK, Giannotti TE, Van Hoof TJ, et al. Understanding barriers to participation in mammography by women with disabilities. Am J Health Promot 2008;22:381–5. 10.4278/ajhp.22.6.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eurostat. European Health Interview Survey (EHIS). Description of the dataset. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-health-interview-survey (accessed 17 May 2018).

- 28. Eurostat. European Health Interview Survey (EHIS wave 2) Methodological manual. Eurostat Methodologies and Working Papers. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. 2013. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5926729/KS-RA-13-018-EN.PDF/26c7ea80-01d8-420e-bdc6-e9d5f6578e7c (accessed 23 Nov 2018).

- 29. Office for National Statistics. Health indicators for the United Kingdom and its constituent countries based on the 2013 to 2014 European Health Interview Survey, (Wave 2). 2015. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ (accessed 23 May 2018).

- 30. Office for National Statistics, Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. European Health Interview Survey: United Kingdom Data, Wave 2, 2013-2014. UK Data Service SN: 7881. 2016. https://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/catalogue/?sn=7881 (accessed 17 May 2018).

- 31. Eurostat. European Health Interview Survey (EHIS). Reference Metadata in Euro SDMX Metadata Structure (ESMS). 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/hlth_det_esms.htm#conf1472805901915 (accessed 20 May 2018).

- 32. Allison P. Listwise deletion: It’s NOT evil. Statistical Horizons. http://statisticalhorizons.com/listwise-deletion-its-not-evil (accessed 30 May 2018).

- 33. Cancer Research UK. Breast screening. 2017. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/breast-cancer/screening/breast-screening (accessed 24 Nov 2018).

- 34.Cardiff Welsh Government. All Party Parliamentary Group on Cancer. Report of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Cancer’s Inquiry into Inequalities in Cancer. 2009. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/Campaigns/InquiryintoInequalitiesReport.pdf (accessed 30 May 2018).

- 35. Bone A, McGrath-Lone L, Day S, et al. Inequalities in the care experiences of patients with cancer: analysis of data from the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey 2011-2012. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004567 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Merten JW, Pomeranz JL, King JL, et al. Barriers to cancer screening for people with disabilities: a literature review. Disabil Health J 2015;8:9–16. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu SY, Clark MA. Breast and cervical cancer screening practices among disabled women aged 40–75: does quality of the experience matter? J Womens Health 2008;7:1321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yen SM, Kung PT, Tsai WC. Factors associated with free adult preventive health care utilization among physically disabled people in Taiwan: nationwide population-based study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:610 10.1186/s12913-014-0610-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leung J, Macleod C, McLaughlin D, et al. Screening mammography uptake within Australia and Scotland in rural and urban populations. Prev Med Rep 2015;2:559–62. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hewitt M, Devesa SS, Breen N. Cervical cancer screening among U.S. women: analyses of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med 2004;39:270–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodríguez MA, Ward LM, Pérez-Stable EJ. Breast and cervical cancer screening: impact of health insurance status, ethnicity, and nativity of Latinas. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:235–41. 10.1370/afm.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Independent Cancer Taskforce. Achieving World-Class Cancer Outcomes: a Strategy for England 2015-2020. 2016. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-us/cancer-strategy-in-england (accessed 30 May 2018).

- 43. Welsh Government. Together for Health- Cancer Delivery Plan; A Delivery Plan up to 2016 for NHS Wales and its Partners. Cardiff: Welsh Government, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yeo R, Moore K. Including disabled people in poverty reduction work: “nothing about us, without us”. World Dev 2003;31:571–90. 10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00218-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pinto PC. Women, disability, and the right to health : Hobbs M, Rice C, Gender and Women’s Studies: Critical Terrain. Toronto: Women’s Press, 2018:465–79. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.