Abstract

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) including permanent paraplegia constitutes a common complication after repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. The staged-repair concept promises to provide protection by inducing arteriogenesis so that the collateral network can provide a robust blood supply to the spinal cord after intervention. Minimally invasive staged segmental artery coil embolisation (MIS2ACE) has been proved recently to be a feasible enhanced approach to staged repair.

Methods and analysis

This randomised controlled trial uses a multicentre, multinational, parallel group design, where 500 patients will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to standard aneurysm repair or to MIS2ACE in 1–3 sessions followed by repair. Before randomisation, physicians document whether open or endovascular repair is planned. The primary endpoint is successful aneurysm repair without substantial SCI 30 days after aneurysm repair. Secondary endpoints include any form of SCI, mortality (up to 1 year), length of stay in the intensive care unit, costs and quality-adjusted life years. A generalised linear mixed model will be used with the logit link function and randomisation arm, mode of repair (open or endovascular repair), the Crawford type and the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (euroSCORE) II as fixed effects and the centre as a random effect. Safety endpoints include kidney failure, respiratory failure and embolic events (also from debris). A qualitative study will explore patient perceptions.

Ethics and dissemination

This trial has been approved by the lead Ethics Committee from the University of Leipzig (435/17-ek) and will be reviewed by each of the Ethics Committees at the trial sites. A dedicated project is coordinating communication and dissemination of the trial.

Trial registration number

Keywords: thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms, taaa, spinal cord injury, sci, segmental artery coil embolization, misace

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a particularly large multicentre randomised controlled trial in aortic surgery addressing a fundamental issue in thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

The trial includes open and endovascular repair.

It provides important 1-year data on spinal cord injury and mortality.

Paraplegia Prevention in Aortic Aneurysm Repair by Thoracoabdominal Staging looks at potential reductions in bleeding complications and endoleaks.

Because of the nature of the intervention, it cannot be blinded.

Introduction

This publication describes the study design and protocol of a clinical trial on Paraplegia Prevention in Aortic Aneurysm Repair by Thoracoabdominal Staging (‘PAPAartis’) and follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) recommendations very closely.1 2

Background

Aortic aneurysms are permanent and localised dilations of particular portions of the aorta that grow unpredictably but with a mean estimated rate of about two millimetres per year3 and remain asymptomatic for long periods of time. Based on the aneurysm localisation, one can distinguish between thoracic, abdominal and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (TAAAs). The latter are complex and generally categorised according to the Crawford classification (types I–IV), based on the anatomic extent of the aneurysm.4–6

A study comparing a historic cohort to a matched treated population showed that the dismal 5-year survival rate of 13% given the natural course of the disease could be increased to 61% with open surgical repair.7 Although successful aortic repair cures the disease, both open and endovascular modalities can result in paraplegia from spinal cord ischaemia, and mortality is high. This particularly affects patients with aneurysms extending from the thoracic to the abdominal aorta and thus involving many segmental arteries (SAs) supplying the spinal cord. It has been assumed that paraplegia in open repair arises primarily due to temporary interruption of spinal cord blood supply during the operative procedure with a duration sufficient to damage cell bodies and nerve tracts in the spinal cord irreversibly. In endovascular repair, the chronic occlusion of several SAs (as well as the temporary compromising of internal iliac blood supply during the procedure) induces paraplegia with a comparable incidence.8 Various adjunctive perioperative neuroprotective strategies, such as motor/somatosensory evoked potential monitoring, meticulous perioperative blood pressure management, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage and even local spinal cord cooling, have been introduced to minimise ischaemic spinal cord injury (SCI).9 These methods have achieved a notable decrease in the incidence of paraplegia and paraparesis, but it remains high with an incidence of up to 20% for Crawford type II aneurysms.10

Rationale

Members of the study team have found that the deliberate staged occlusion of SAs leading to the paraspinous collateral network and finally supplying the spinal cord can trigger arterial collateralisation, thus stabilising blood supply to the spinal cord from alternate inflow sources and potentially preventing ischaemia.11–16 This approach was devised after years of research that included recognition of the body’s ability to tolerate SA sacrifice17 given haemodynamic stability18 19 along with the identification of the paraspinous arterial collateral network itself.12 16 One means of occluding arteries in the clinical setting has been termed ‘minimally invasive staged segmental artery coil embolisation’ (MIS²ACE), which was proved feasible in 2015.20 A consecutive case series of over 50 patients lends credence to its safety.21 This is thus the ideal time to carry out such a trial, where the need to test efficacy, effectiveness and safety are paramount but before it has gained acceptance despite lack of evidence.

Objectives

The primary objective of the PAPAartis trial is to test the hypothesis that MIS²ACE can greatly reduce the incidence of ischaemic SCI and mortality compared with standard open surgical or endovascular thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair alone.

Trial design

PAPAartis is a multinational, open-label, randomised controlled trial. It has two parallel groups with equal allocation, and the primary endpoint is to be tested in a superiority framework.

Methods and analysis

Study setting

To demonstrate the efficacy of MIS²ACE while minimising risks, we chose participating sites with great expertise in the treatment of TAAA and tried to create a balance between those specialising in open and those in endovascular repair. The trial is jointly funded by the European Union as part of the Horizon 2020 programme and by the German Research Foundation, resulting in sites exclusively in Europe and with a strong emphasis on Germany. The recruiting sites (n=29) at commencement of the trial come from Austria (n=2), France (n=2), Germany (n=16), Italy (n=2), the Netherlands (n=1), Poland (n=2), Sweden (n=2), Switzerland (n=1) and the UK (n=1). In addition, Denmark provides an independent radiological core unit, Spain heads projects on health economics and patient satisfaction, the USA provides expert advice and Scotland heads a project on communication and dissemination. Patient recruitment will begin imminently and is planned to last 2 years.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

TAAA, Crawford type II or III (verified by radiological core unit).

Planned open or endovascular repair of aneurysm within 4 months.

≥18 years old.

The inclusion criteria are chosen to select a high risk (Crawford type II and III) population amenable to MIS²ACE therapy.

Key exclusion criteria

Complicated (sub)acute type B aortic dissection (but all chronic type B dissections will be included).

Ruptured and urgent aneurysm (emergencies).

Untreated aortic arch aneurysm (patients with a previous successful aortic arch aneurysm repair may be included independent of technique used).

Bilaterally occluded iliac arteries or chronic total occlusion of left subclavian artery.

Preoperative neurological deficits or spinal cord dysfunction

Major untreated cardiopulmonary disease.

Life expectancy of less than 1 year.

High risk for SA embolism (‘shaggy’ aorta).

Severe contrast agent allergy and severe reduction in glomerular filtration rate.

The first two exclusion criteria were chosen since patients should not be subjected to additional risk as a result of the waiting time in the MIS²ACE arm before TAAA repair can be performed. The third exclusion criterion was chosen since these patients have considerable risk unrelated to the focus of the trial. Exclusion criterion 4 was chosen, since sufficient blood supply after MIS²ACE cannot be guaranteed, and the prior occlusion implies that no additional treatment options are available in this anatomic region.

Intervention

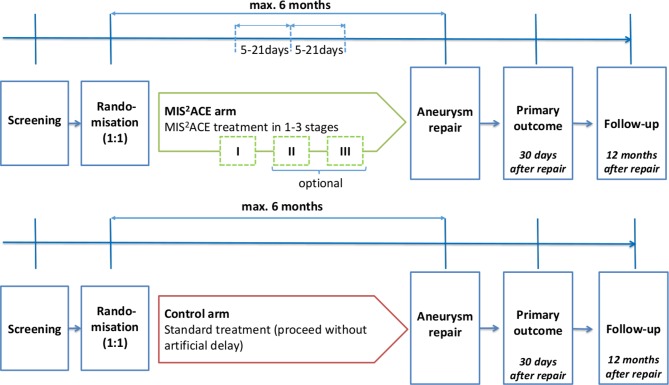

An overview of the trial is provided in figure 1. The treating physicians choose the mode of repair, after which the patient is randomised to the interventional or the control arm.

Figure 1.

Schematic portrayal of the participant timeline and visit schedule for the PAPAartis trial. MIS2ACE, minimally invasive staged segmental artery coil embolisation; PAPAartis, Paraplegia Prevention in Aortic Aneurysm Repair by Thoracoabdominal Staging.

In the interventional arm (MIS²ACE), SAs will be occluded in one to three sessions some weeks before the aneurysm repair. Target SAs for coil/plug deployment will be identified considering the extent of the planned repair and individual SA anatomy. The occlusion of up to seven SAs will be performed in a single session and conducted through a peripheral artery access (eg, the common femoral artery) in local anaesthesia. Local anaesthesia is important so that patients can provide immediate feedback regarding potential neurological symptoms. Selected SAs will be catheterised (eg, with a 5F catheter or 2.7F microcatheter). Microcoils or vascular plugs will be used for the occlusion itself, not however particles, which could cause unwanted microembolisms to the spinal cord directly. This will be performed in the proximal SA to ensure that the collateral network itself is not affected. The procedure may be done without spinal fluid drainage, but this is left at the discretion of the centre. The length of the procedure, the amount of contrast dye and the dose of radiation will be documented exactly. The recommended interval between sessions is 21 days, with a strict safety minimum of 5 days.11 Experts in endovascular catheterisation in small vessels (eg, cardiovascular surgeons, interventionalists, endovascular surgeons, interventional radiologists and paediatric cardiologists) will perform MIS²ACE. It is essential to maintain blood pressure above 140 mm Hg, but for patients with hypertension, it is imperative that the postoperative pressure should not fall below their individual preoperative systolic blood pressure during and after the procedure (invasive monitoring), ideally for at least 2 days. Antihypertensive drugs have to be adjusted accordingly. Therefore, the patient should stay in the Intermediate Care Unit (IMCU) for at least 48 hours, preferably longer. Reduction or even interruption of oral antihypertensive medication and use of low-dose vasopressors may be used and are preferable to volume therapy, which increases central venous pressure and thereby also CSF pressure.

In the control arm, treatment will be according to the optimal state-of-the art procedures at the local site. This ensures a real-world comparison in which the control arm is as strong as possible.

As the trial proceeds, statistical monitoring and concomitant projects may identify need for revisions to the intervention. These alterations will then be adopted with protocol amendments to optimise patient safety.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is successful treatment of the aneurysm. We define ‘success’ as: (A) the patient is alive and without substantial SCI 30 days after treatment and (B) the aneurysm did not rupture and was excluded within 6 months of randomisation.

Patients who have not been treated within 6 months of randomisation will be treated as failures to ensure that success/failure is defined for all randomised patients. This facilitates the intention-to-treat analysis (see below) and reduces the amount of missing data. During recruitment, the Trial Steering Committee will ensure that time lapse alone leads only very rarely to failure; otherwise, this criterion will be reworked. The definition of success pertaining to mortality and SCI will be assessed 30 days after TAAA repair, and ‘substantial SCI’ means that the patient is unable to stand without assistance and is defined using the modified Tarlov scale22 (see below) and assessed by a board certified neurologist whenever possible:

0: no lower extremity movement.

1 : lower extremity motion without gravity.

2: lower extremity motion against gravity.

3: able to stand with assistance.

4: able to walk with assistance.

5: normal.

A training video describing this scale is provided for study personnel.

Treatment success for open repair is defined by complete resection and graft replacement in the absence of major related complications.

Secondary endpoints

For secondary endpoints, treatment success will be assessed and based on follow-up CT/MR images. Treatment success for endovascular repair is defined based on the position paper of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and the European Society of Cardiology, in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions23 and takes into account upcoming guideline papers. Failure is defined as substantial progression of the aneurysm sac (>3 mm) or the presence of major related complications (eg, type I/III endoleaks). Completion angiography and/or follow-up MRI/CT from patients with endovascular repair will be conducted as part of clinical routine and will be sent to Copenhagen for assessment.

Note: the point in time ‘1 year’ refers to 1 year after TAAA repair. If patients retained in the full analysis set have not had a repair, then ‘30 days after TAAA repair’ and ‘at 1 year’ will be treated as 30 days and 1 year after randomisation.

Substantial SCI at 30 days after TAAA repair and at 1 year.

SCI according to the modified Tarlov scale from TAAA repair treatment to 1 year.

All-cause mortality at 30 days and 1 year after TAAA repair.

Length of stay in intensive care unit and intermediate care unit after TAAA repair.

Subgroup analyses for open repair and endovascular repair separately.

Reoperation for bleeding and drainage volumes in the first 24 hours and use of blood products (only for open repair).

Cross-clamping times during open surgery.

Residual aneurysm sac perfusion, that is, type II endoleaks (only for endovascular repair).

Health-related quality of life will be collected using the WHOQOL-BREF24 and the EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L instruments.25 Hospital and other healthcare resource use will be collected. Healthcare costs, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) over 1 year will be calculated.26

Safety endpoints

Beyond adverse event (AE)/serious adverse event (SAE) reporting and descriptive statistics on radiation exposure, the following issues will receive special attention: acute kidney injury (AKI), respiratory failure and embolic events (also from debris). AKI is defined using the major adverse kidney events (MAKE) criteria,27 comparing baseline to the time-point of the primary outcome, where we note that the nature of the trial and logistics of the visits preclude the use of MAKE at precisely 90 days (MAKE90). We also record new dialysis separately and deterioration in chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage by at least two stages. AKI and CKD will be distinguished. Having identified particular safety risks in the trial aids us in collecting appropriate data, assessing and reporting these harms, as recommended by SPIRIT.1 2 We do not use these to define stopping criteria however, which is left at the discretion of the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC).

Participant timeline

Please refer to figure 1 for details of the visit schedule and participant timeline.

Sample size and recruitment

Estimates of effect size are difficult for several reasons. Foremost, there are large discrepancies between outcome rates quoted in the literature. Moreover, the impact of recent improvements in techniques on outcomes cannot yet be quantified accurately, and finally, the effect size depends on the improvement due to the trial intervention which, in turn, depends on anatomy, postrepair management and other complex factors. Taking a random effects model of the data from large recent publications for open10 28–30 and endovascular repair,31–33 one finds an estimated incidence of 18% (95% prediction interval 15% to 23%) for open repair and a very uncertain 24% (2% to 79%) for endovascular repair. The prediction interval as opposed to the CI provides the correct bounds for what can be expected in the trial.34 The resources and time available to the study allow for the recruitment of 500 patients. Assuming success rates of 80% in the control arm and 90% in the intervention arm and using a group-sequential design35 with two interim analyses, this then implies a power of just over 87%.36 The definitions of the primary endpoint and the full analysis set imply that only very few dropouts are to be expected for this analysis and that compliance will not be a problem. The severity of the therapy and recovery times mean that loss to follow-up is not expected to be a major factor.

The planned recruitment is between 8 and 9 patients per site per year. This is roughly half the number of patients that meet the inclusion criteria. However, slow recruitment plagues many trials and mitigation strategies have already been developed. A list of interested recruitment sites (n>10) is being collected to expand the consortium. Statistical monitoring will be used to identify reasons for screened patients not being included in the trial so that minor and clinically justified amendments to the trial protocol can address these issues, for example, through adjustments to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, a newsletter including recruitment by site will be distributed at regular intervals to spawn healthy competition among the team members.

Randomisation

Patients will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention and control arms with a random number generator. Randomisation will be performed online at the recruitment centres with a tool prepared and hosted by the Clinical Trial Centre Leipzig.

Some of the centres are expected to recruit a very small number of patients, meaning that block randomisation stratified by centre is unfeasible. Although minimisation schemes could be used to attain roughly balanced allocation of patients, even at the centre level, there is controversy about the methods needed to analyse such trials. To avoid potential complexities in analysis, we have thus opted for a very simple randomisation scheme, knowing that small imbalances in the number of patients per arm are to be expected.

Selected data collection methods

Neurological examinations will be performed by board certified neurologists whenever possible. If such an examination is made on discharge and no signs of impairment are found, then verification that this holds at 30 days is only required by telephone. Any signs of impairment necessitate a full examination at 30 days however.

If the assessment of Crawford classification or successful treatment carried out by the radiological unit in Copenhagen should disagree with the treating physician’s opinion, the blinded independent endpoint committee will make the final decision. The definition of success does not necessarily require that the MRI/CT be made within 6 months of randomisation. Later verification of success is acceptable.

Data management

The EDC tool SecuTrial, developed and distributed by interActive Systems GmbH, is used for creation of the study database. Data entry uses electronic case report form (eCRF) data entry masks, and data changes are tracked automatically including date, time and person who entered/changed information (audit trail). Major corrections or major missing data have to be explained.

The information entered into the eCRF by the investigator or an authorised member of the study team is systematically checked for completeness, consistency and plausibility by routines implemented in the database, such that discrepancies can be dealt with at data entry. Errors and warnings are listed in a validation report and can be resolved at any time during the data entry process. On completion of data entry, the site staff flags the eCRF pages as ‘data entry completed’.

Throughout the study, a backup of all data is made daily. Unauthorised access to patient data is prevented by the access concept of the study database, which is based on strict file system permission.

At the end of the study, once the database is complete and accurate, the database will be locked. Subsequent changes to the database are possible only by joint written agreement between coordinating investigator, trial statistician and data manager.

Statistical methods

Analysis sets

If patients retract informed consent before any procedure is performed (repair or SA occlusion), they will be excluded from the primary analysis, since we expect some control arm patients to be dissatisfied with their assigned treatment, retract consent and seek MIS²ACE outside of the trial. Including them would be anticonservative. The full analysis set (FAS) includes all randomised patients that have had a session for occluding SAs (intervention arm) or have had a repair procedure (conventional arm). Randomised patients whose aneurysm ruptures or who die from any cause will be included in the FAS, irrespective of the above stipulations.

If a sufficiently large number of patients violate the trial protocol, particularly regarding the trial intervention, then a per-protocol analysis will be performed using the set of patients that conformed to the major terms in the protocol. A precise definition of the per protocol set will be provided in the statistical analysis plan.

Patients are generally analysed regarding safety according to treatment received. In our case, an undue delay between randomisation and treatment is a risk factor, meaning that such patients will be included in the safety analyses even if they have not yet received treatment.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis is an intention-to-treat analysis based on the FAS and makes use of a generalised linear mixed model with the logit link function. The success/failure of treatment will be the dependent variable. The assigned randomisation arm, mode of repair (open or endovascular repair), the Crawford type and the euroSCORE II are fixed effects, and the centre will be treated as a random effect. The euroSCORE II already takes age, sex and other relevant factors into account. The interaction term between the randomisation arm and the other fixed effects will only be included if evidence for a strong interaction effect are seen, since this would otherwise lead to a substantial loss of power.37 38 As a supplementary analysis, an analogous mixed model will be performed with a unity link function to provide estimates and confidence intervals for absolute risk differences.

The definitions of the full analysis set and the primary endpoint are chosen so that almost no missing data are expected. If success cannot be ascertained with certainty, the patient will be treated as a failure. Sensitivity analyses will be used to gauge the effect of missing data on the estimates and conclusions drawn.

Interim analyses are planned 30 days after 50% of patients (n=250) and 75% (n=375) have been treated for the aneurysm. The primary endpoint will be analysed, and randomisation can be terminated for efficacy if a p value of 0.0030 (first interim analysis) or 0.018 (second interim analysis) is reached. The p value for demonstrating efficacy in the final analysis is 0.044.

Analysis of binary secondary outcomes will be treated on the same footing as the primary analysis. Mortality at 30 days will be treated as binary as opposed to time to event, since prolonging life in the postoperative phase for a matter of days is not considered clinically relevant. Subgroup analyses of the two Crawford types and of the two modes of repair will be presented in the form of contingency tables. Mixed model Cox regression with covariates euroSCOREII, Crawford type and mode of repair will be used for 1-year mortality with randomisation arm as the independent variable of interest and centre as a random effect. If the assumption of proportional hazards is violated substantially, a logistic regression will be used. Kaplan-Meier curves will be used to represent the data.

In explorative analyses, the number of patent SAs and the number occluded will be taken into account with respect to SCI and mortality. The anatomical position of the SAs may also be used.

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) time and IMCM time will be analysed with a linear mixed effects model with the same fixed and random effects as in the primary analysis and may be log transformed if warranted. Reoperation for bleeding and type II endoleaks will be presented for the subgroups of patients treated with open or endovascular repair, respectively.

Descriptive statistics will be used for further safety outcomes along with ORs according to treatment received, as appropriate.

Total mean cost per patient over 1 year will be estimated by multiplying healthcare resource use collected in the trial by unit costs from the country health system.39 QALYs will be calculated in each treatment group using the EQ-5D-5L value set.40 The ICER will be calculated and will inform whether MIS²ACE is cost-effective on average for patients with TAAA Crawford type II or III. Bootstrap methods will be used to characterise uncertainty.26

Further details will be provided in a statistical analysis plan.

Statistical monitoring

The trial conduct will be closely supervised by means of central and statistical monitoring. The objectives are: (A) to detect safety relevant signals as soon as possible, (B) to detect non-compliance and relevant protocol violations and to prevent their future occurrence by prompt reaction, (C) to prevent missing visits or measurements by prompt reminders and (D) to explore means of improving on the MIS2ACE procedure.

Statistical and central monitoring will start immediately after inclusion of the first patient. The relevant reports and descriptive statistics will be updated and discussed at the regular meetings of the Leipzig study team. Problems and abnormalities will be presented at regular intervals to the coordinating investigator.

On-site monitoring

A risk-based monitoring strategy will be implemented as required by International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) E6 (Chapter 5.0) According to the risk analysis, treatment delivery parameters, adverse events, follow-up information, data transmission and protection and informed consent documents comprise risk-bearing trial aspects and will be monitored.

Prior to recruitment, each participating centre will receive a site initiation visit, during which the trial protocol (if necessary) and the eCRFs will be reviewed with centre staff and any necessary training will be provided. During the study, trial monitors will maintain regular contact with trial centre staff (by telephone/fax/email/post) to track the progress of the trial, respond to any problems and provide general assistance and support.

The first regular monitoring visit at a site will take place after the randomisation of the site’s first patient to check protocol compliance and to prevent further systematic errors due to misunderstandings. Trial site visits will take place on a regular basis. The frequency of monitoring visits will depend on the trial site’s recruitment rate as well as on potential problems detected during previous on-site visits or by central monitoring.

Prior to every scheduled on-site visit, the monitor will receive summaries of the site’s patient data already documented in the database and if applicable with data indicating possible protocol deviations or inconsistencies. During the visits, the monitor will: (A) check informed consent forms of all patients enrolled, (B) perform source data verification of key data in a random sample of at least 20% of the site’s patients, (C) perform targeted source data verification for patients with possible deviations, (D) discuss open queries raised by data management or drug safety personnel, (E) check essential parts of the investigator site file, (F) check source data for AEs or SAEs, which have not been properly reported in the CRF/eCRF and (G) check for major Good Clinical Practice (GCP) breaches and/or protocol violations.

Harms

Safety endpoints related directly to MIS2ACE include kidney failure, respiratory failure and embolic events (also from debris). These endpoints will be listed according to treatment received with a breakdown according to the number of MIS2ACE sessions. In addition, data on radiation exposure will be collected and presented descriptively.

Patient and public involvement

The trial protocol was developed in part by physicians with years of experience in treating patients with TAAA. Their experience indicated that paraplegia is the greatest concern that patients have when deliberating on whether to be treated and was thus chosen along with mortality for the primary outcome. A qualitative study will recruit about 30 patients after surgical wound healing for one-on-one in-depth interviews in different sites of the trial. Purposive sampling will be used to select information-rich cases to be interviewed, according to criteria of clinical outcome, age, gender and other patient social variables as social class or ethnicity. The finalisation of the data collection process will be determined following the principle of theoretical saturation. Interviews will take place with an experienced qualitative researcher in the patient’s own language in a mutually convenient, private, comfortable place. A literature review will be conducted to broadly inform the interview guide, though patients will be encouraged to speak freely. The goal is for the patient to express in his or her own words the impact on their life of diagnosis and treatment and look at changes that occur in quality of life, family, work, lifestyle and social environment from an ethnographic standpoint. The interviews will be recorded and transcribed literally. Summative content analysis will be performed using NVivo software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Patients and the public have not yet been involved directly in the trial.

Ethics and dissemination

Approval and registration

The Federal Office for Radiation Protection in Germany has also approved the additional radiation use in the intervention group (Z5-22462/2 – 2017–073). The trial has been registered with clinicaltrials.gov. Amendments to the protocol will be reviewed by Ethics Committees. Informed consent will be obtained before collecting any patient data and patient information.

External boards

A DMC has been established to oversee patient safety and data quality in the trial. It consists of three members with expertise in aortic surgery, neurology and medical statistics. The DMC charter states that its role is to ‘safeguard the interests of trial participants, assess the safety and efficacy of the interventions during the trial, and assist and advise the trial steering committee to protect the validity and credibility of the trial. In order to do this, the DMC evaluates the results of the regular reports and their influence on the risk assessment for the patients as well as for the integrity of the trial. The DMC gives its recommendations at regular intervals as to whether the continuation of the trial is justifiable’. Only the trial statistician and the DMC members will have access to the interim analyses until the end of the trial. At the inaugural meeting, the members of the DMC will be asked to discuss whether SAEs related to the MIS2ACE procedure should be sent to them without delay.

An expert advisory board consisting of four international experts on TAAA repair provides the active trial members with independent advice regarding trial design and conduct. It meets with leading members of the consortium on an annual basis and is kept abreast of the trial’s progress.

Dissemination

One project partner (MODUS Research and Innovation, Edinburgh, Scotland) has a project dedicated to communication and dissemination. Key channels, tools and target audiences for dissemination and use of project results will be identified in a communication and dissemination plan. The dissemination activities will be twofold: basic communication about the project to the public and specific dissemination to four target communities. One objective of the dissemination plan will be to support the project partners with the clinical recruitment. The other objective will be to reach out to wide audiences outside the project consortium at national, European and international levels (medical and health professionals, academics, medical and biomedical industries, policy makers, EU regulators [eg, the European Medicines Agency], patients groups, health non-governmental organisations, civil societies, scientific and lay media). The dissemination vehicles will be seminars, medical conferences and publications and project partners’ individual communication streams. Dissemination material may include a project leaflet, newsletter, press releases and a trial website.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DP: study conception and design, statistical methods and sample size calculations and writing and reviewing of the manuscript. MC, TK, GM, KvA and JH: study design with particular focus on cardiovascular endpoints and reviewing of the manuscript. LL: study design with particular focus on radiological methods and reviewing of the manuscript. PN and KP: study design, ethics, data management and writing and reviewing of the manuscript. JP: study design with particular focus on neurological methods and endpoints and reviewing of the manuscript. DME: study design with particular focus on health economics and patient satisfaction and reviewing of the manuscript. NR-A: study design for portion on qualitative patient satisfaction and reviewing of the manuscript. CDE: research that lay foundation for trial, initial study conception, study design and writing and reviewing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement 733203 and from the German Research Foundation under grant number ET 127/2-1.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The trial protocol and the informed consent form have been reviewed and approved by the lead Ethics Committee from the University of Leipzig (435/17-ek) and will be reviewed by each of the Ethics Committees at the trial sites.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elefteriades JA. Natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysms: indications for surgery, and surgical versus nonsurgical risks. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:S1877–S1880. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04147-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crawford ES, Crawford JL, Safi HJ, et al. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms: preoperative and intraoperative factors determining immediate and long-term results of operations in 605 patients. J Vasc Surg 1986;3:389–404. 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elefteriades JA. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: reading the enemy’s playbook. Curr Probl Cardiol 2008;33:203–77. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frederick JR, Woo YJ. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2012;1:277–85. 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.09.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller CC, Porat EE, Estrera AL, et al. Number needed to treat: analyzing of the effectiveness of thoracoabdominal aortic repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2004;28:154–7. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greenberg RK, Lu Q, Roselli EE, et al. Contemporary analysis of descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: a comparison of endovascular and open techniques. Circulation 2008;118:808–17. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Etz CD, Weigang E, Hartert M, et al. Contemporary spinal cord protection during thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic surgery and endovascular aortic repair: a position paper of the vascular domain of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;47:943–57. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conrad MF, Crawford RS, Davison JK, et al. Thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: a 20-year perspective. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:S856–S861. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Etz CD, Homann TM, Plestis KA, et al. Spinal cord perfusion after extensive segmental artery sacrifice: can paraplegia be prevented? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:643–8. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Etz CD, Kari FA, Mueller CS, et al. The collateral network concept: remodeling of the arterial collateral network after experimental segmental artery sacrifice. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:1029–36. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zoli S, Etz CD, Roder F, et al. Experimental two-stage simulated repair of extensive thoracoabdominal aneurysms reduces paraplegia risk. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:722–9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luehr M, Salameh A, Haunschild J, et al. Minimally invasive segmental artery coil embolization for preconditioning of the spinal cord collateral network before one-stage descending and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Innovations 2014;9:60–5. 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geisbüsch S, Stefanovic A, Koruth JS, et al. Endovascular coil embolization of segmental arteries prevents paraplegia after subsequent thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: an experimental model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:220–7. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Etz CD, Kari FA, Mueller CS, et al. The collateral network concept: a reassessment of the anatomy of spinal cord perfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:1020–8. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Etz CD, Halstead JC, Spielvogel D, et al. Thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: is reimplantation of spinal cord arteries a waste of time? Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:1670–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Etz CD, Homann TM, Luehr M, et al. Spinal cord blood flow and ischemic injury after experimental sacrifice of thoracic and abdominal segmental arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:1030–8. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Etz CD, Luehr M, Kari FA, et al. Paraplegia after extensive thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: does critical spinal cord ischemia occur postoperatively? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;135:324–30. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Etz CD, Debus ES, Mohr FW, et al. First-in-man endovascular preconditioning of the paraspinal collateral network by segmental artery coil embolization to prevent ischemic spinal cord injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;149:1074–9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Branzan D, Etz CD, Moche M, et al. Ischaemic preconditioning of the spinal cord to prevent spinal cord ischaemia during endovascular repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm: first clinical experience. EuroIntervention 2018;14:828–35. 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chiesa R, Melissano G, Marrocco-Trischitta MM, et al. Spinal cord ischemia after elective stent-graft repair of the thoracic aorta. J Vasc Surg 2005;42:11–17. 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grabenwöger M, Alfonso F, Bachet J, et al. Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) for the treatment of aortic diseases: a position statement from the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;42:17–24. 10.1093/ejcts/ezs107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol Med 1998;28:551–8. 10.1017/S0033291798006667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1717–27. 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II-An ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health 2015;18:161–72. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Billings FT, Shaw AD. Clinical trial endpoints in acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract 2014;127:89–93. 10.1159/000363725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fehrenbacher JW, Siderys H, Terry C, et al. Early and late results of descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm open repair with deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;140(6 Suppl):S154–S160. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zoli S, Roder F, Etz CD, et al. Predicting the risk of paraplegia after thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:1237–45. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, Preventza O, et al. Outcomes of 3309 thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repairs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:1323–38. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katsargyris A, Oikonomou K, Kouvelos G, et al. Spinal cord ischemia after endovascular repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms with fenestrated and branched stent grafts. J Vasc Surg 2015;62:1450–6. 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.07.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bisdas T, Panuccio G, Sugimoto M, et al. Risk factors for spinal cord ischemia after endovascular repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2015;61:1408–16. 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dias NV, Sonesson B, Kristmundsson T, et al. Short-term outcome of spinal cord ischemia after endovascular repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015;49:403–9. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 2011;342:d549 10.1136/bmj.d549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 1979;35:549–56. 10.2307/2530245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hintze J. Pass. 11 Kaysville, Utah, USA: NCSS, LLC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aitkin M. The Analysis of Unbalanced Cross-Classifications. J R Stat Soc Ser A 1978;141:195 10.2307/2344453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nelder JA. A Reformulation of Linear Models. J R Stat Soc Ser A 1977;140:48 10.2307/2344517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stenberg K, Lauer JA, Gkountouras G, et al. Econometric estimation of WHO-CHOICE country-specific costs for inpatient and outpatient health service delivery. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2018;16:11 10.1186/s12962-018-0095-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM, Greiner W. German Value Set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics 2018;36:663–74. 10.1007/s40273-018-0615-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.