Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to determine whether regional analgesia with intrathecal morphine (ITM) in an enhanced recovery programme (enhanced recovery after surgery [ERAS]) gives a shorter hospital stay with good pain relief and equal health-related quality of life (QoL) to epidural analgesia (EDA) in women after midline laparotomy for proven or assumed gynaecological malignancies.

Design

An open-label, randomised, single-centre study.

Setting

A tertiary referral Swedish university hospital.

Participants

Eighty women, 18–70 years of age, American Society of Anesthesiologists I and II, admitted consecutively to the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Interventions

The women were allocated (1:1) to either the standard analgesic method at the clinic (EDA) or the experimental treatment (ITM). An ERAS protocol with standardised perioperative routines and standardised general anaesthesia were applied. The EDA or ITM started immediately preoperatively. The ITM group received morphine, clonidine and bupivacaine intrathecally; the EDA group had an epidural infusion of bupivacaine, adrenalin and fentanyl.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary endpoint was length of hospital stay (LOS). Secondary endpoints were QoL and pain assessments.

Results

LOS was statistically significantly shorter for the ITM group compared with the EDA group (median [IQR]3.3 [1.5–56.3] vs 4.3 [2.2–43.2] days; p=0.01). No differences were observed in pain assessment or QoL. The ITM group used postoperatively the first week significantly less opioids than the EDA group (median (IQR) 20 mg (14–35 mg) vs 81 mg (67–101 mg); p<0.0001). No serious adverse events were attributed to ITM or EDA.

Conclusions

Compared with EDA, ITM is simpler to administer and manage, is associated with shorter hospital stay and reduces opioid consumption postoperatively with an equally good QoL. ITM is effective as postoperative analgesia in gynaecological cancer surgery.

Trial registration number

NCT02026687; Results.

Keywords: regional analgesia, gynecological malignancy, laparotomy, opioid consumption, quality improvement

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study evaluates quality improvement on postoperative recovery after gynaecological cancer surgery in an enhanced recovery after surgery setting.

The study is an open randomised controlled trial.

The experimental treatment (intrathecal morphine) was compared with the standard care of postoperative analgesia (epidural analgesic) used in our setting.

The objective was to compare the two analgesic methods in a clinical relevant multimodal context, not to find the appropriate doses or types of analgesic agent for each method.

Introduction

Pain is an important component in the assessment of health-related quality of life (QoL). Besides the human suffering, insufficiently treated postoperative pain complicates mobilisation, increases the risk for complications and might prolong hospitalisation.

Regional analgesia with epidural analgesia (EDA) in abdominal surgery is recommended in most enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols for use both during surgery and postoperatively.1 2 Single-dose intrathecal morphine provides good analgesia during the first postoperative days after abdominal cancer surgery,3–6 and improves the recovery after hysterectomy for benign conditions.7 8 An additional analgesic effect can be obtained by adding the α-adrenergic agonist clonidine intrathecally.4 9 10 In surgery for malignant gynaecological diseases, intrathecal morphine has been less described, although Kara et al11 in 2012 reported reduced morphine consumption and no increase in side effects. A few randomised studies have compared single-dose intrathecal morphine with continuous EDA after major abdominal surgery, showing disputed results concerning pain relief and hospital stay.12–14

Based on the potential benefits of intrathecal morphine as an effective and technically simple applied postoperative analgesic, we designed this randomised study to compare the effects of a single-dose intrathecal combined morphine and clonidine (ITM) with the standard of care in the hospital using EDA in an ERAS programme for abdominal surgery for proven or assumed gynaecological malignant tumours.

The aim of the study was to determine whether ITM, when compared with EDA in an ERAS programme, shortens hospital stay with a similar patient experienced QoL.

Material and methods

We conducted an open-label, randomised, controlled, single-centre study in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines.15 From March 2014 to January 2016, all women who were admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden due to a proven or assumed gynaecological abdominal malignancy were eligible for the study. Women 18 to 70 years, with WHO performance status <2, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score <3 and speaking Swedish fluently were included. Exclusion criteria were contraindications against regional analgesia, physical or psychiatric disability and surgery where pain could not be expected to be controlled by the regional analgesia. Oral and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

At the preoperative visit, the women were allocated to ITM and EDA, 1:1, from a computer-generated randomisation code,16 using sealed opaque envelopes. The participant was informed about the allocation.

Surgery was conducted through a midline laparotomy with the preoperative intention to obtain macroscopically radical tumour resection. If this was not possible, the tumour burden was either to be reduced to the minimal residual tumour (less than 1 cm in size) or samples were to be obtained, preferably by salpingo-oophorectomy, in order to establish the histopathological diagnosis. Board-certified gynaecological oncologists performed the surgery. The surgical technique used was at the discretion of the surgeon.

All women received thrombosis prophylaxis (tinzaparin 4500 anti-Xa IE subcutaneously) once daily for 28 days beginning the evening before the surgery, and prophylactic antibiotics (1.5 g cefuroxime and 1.0 g metronidazole intravenously as a single dose) before surgery starts.

All women received a standardised premedication with paracetamol 1995 mg. The allocated intervention of regional analgesic was applied prior to commencing the general anaesthesia. The experimental treatment group (the ITM) had an intrathecal combination of a single-dose isobar bupivacaine 15 mg, morphine 0.2 mg and clonidine 75 µg, preferably through a 25G spinal needle. The EDA group had the standard EDA regime used in the hospital. The EDA was performed by a low thoracic puncture. The epidural infusion was started after induction of the general anaesthesia but before surgery by a bolus dose of fentanyl 50–100 µg and a bolus from a mixture of bupivacaine 2.4 mg/mL, adrenalin 2.4 µg/mL and fentanyl 1.8 µg/mL. The same mixture was used as a continuous infusion, typically 4–8 mL/hour, throughout surgery.

General anaesthesia was standardised in both groups: induction with fentanyl and propofol, intubation facilitated with rocuronium and maintenance with sevoflurane. Fentanyl and rocuronium were repeated if needed. All patients had a gastric tube and an indwelling urinary catheter. The gastric tube was removed before waking up the patient. Local anaesthetic (40 mL bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL) was injected prefascially and subcutaneously in the abdominal wall in the area of the skin incision.

After the initial monitoring at the postoperative care unit, the postoperative pain management including surveillance of possible opioid side effects and neurological complications took place at the gynaecological ward and followed the routines outlined by the Swedish Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care.17

The women in the ITM group received oral paracetamol 1330 mg and diclofenac 50 mg, both three times daily started on the day of surgery. Oxycodone 10–20 mg twice daily was added on the first postoperative day.

For the EDA group, a continuous epidural infusion of a mixture of bupivacain 1 mg/mL+adrenalin 2 µg/mL+fentanyl 2 µg/mL including the possibility of additional patient-controlled bolus doses was started postoperatively at the postoperative care unit and continued until the morning of the third postoperative day. The infusion rate, normally 4–8 mL/hour, and bolus doses, normally 2 mL, were decided on by the responsible physician. The patients also had oral paracetamol 1330 mg three times daily, starting on the day of surgery. Oral oxycodone 10–20 mg twice daily and diclofenac 50 mg three times daily were added in the morning of the third postoperative day before removal of the epidural catheter according to the guidelines.17

Rescue opioids were the same for both groups; intravenous morphine, 0.5–1 mg, intravenou or oxycodone 5 mg orally was given if needed. In case of obvious pain relieving failure with the ITM or EDA, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine was started.

To quantify the amount of non-opioid analgesics given, the defined daily dose (DDD) methodology was used.18 All opioids, independent of administration route and including the ITM and the EDA, were converted to an equivalent intravenous morphine dose.19 20

A numerical rating scale (NRS) of 0–10 was used to assess the pain three times daily (08:00, 16:00, 23:00) at rest and at mobilisation, that is, when moving out of bed, raising both legs when in bed or when giving a strong cough.

The standardised criteria for discharge were: the patient was mobilised, tolerated a normal diet, had sufficient pain relief with oral analgesics (NRS ≤4), showed no signs of mechanical bowel obstruction and had voided spontaneously with less than 150 mL residual urine. If the last criterion was not met, the woman went home with the catheter, which was removed policlinically. The discharge criteria were checked twice daily. The decision on discharge was made according to the medical criteria but could be prolonged by social or other practical, personal conditions. Both the de facto hospital length of stay (LOS) and the LOS until the discharge criteria were met were calculated.

The research nurse had telephone contact with the participants the day after discharge and then once a week until 6 weeks postoperatively. Adverse events were registered and graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.21 The study was completed after the 6-week contact.

The QoL was assessed by two commonly used validated generic QoL forms. The EuroQol 5-dimension (EQ-5D) form was completed preoperatively, daily during the first week after surgery then once weekly until the 6-week postoperative visit.22 The Short Form–36 Health Survey (SF-36) form was completed preoperatively (baseline) and 6 weeks postoperatively.23

Trial outcomes

The primary endpoint was the de facto duration of hospital stay (LOS). Secondary outcome measurers were QoL and pain assessments. As secondary post hoc outcomes, we also registered the analgesic consumption, time to meet standardised discharge criteria, proportion of women discharged on the third postoperative day and adverse events.

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the study design or conduct of the study. By assessing QoL as part of the protocol, the patients reported a surrogate measure of the burden of the intervention.

Statistics

Sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome endpoint. From our earlier studies on abdominal hysterectomy using ITM in an ERAS setting,7 the SD for LOS was 0.75 days. Providing that the minimum clinical relevant difference in hospital stay between the groups was 0.5 days, each group should consist of 40 women including a 10% dropout rate in order to show statistical significance at a 5% level (two-sided test) with an 80% power.

Data are presented as median (IQR), mean and (95% CI) or number (percent). χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyse categorical data and Mann-Whitney U-tests and Wilcoxon matched pair tests for continuous data.

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse data measured on more occasions. When p≤0.10 in the analysis of the main effect between groups in the repeated measures ANOVA, the pairwise associations between groups on each single occasion of measurement were analysed using the Bonferroni post hoc test.

The significance level was set at p<0.05. The statistical tests were two-tailed. All analyses were carried out according to intention-to-treat principles using Statistica V.13.2 (Dell Software, 5 Polaris Way, Aliso Viejo, California, USA).

Results

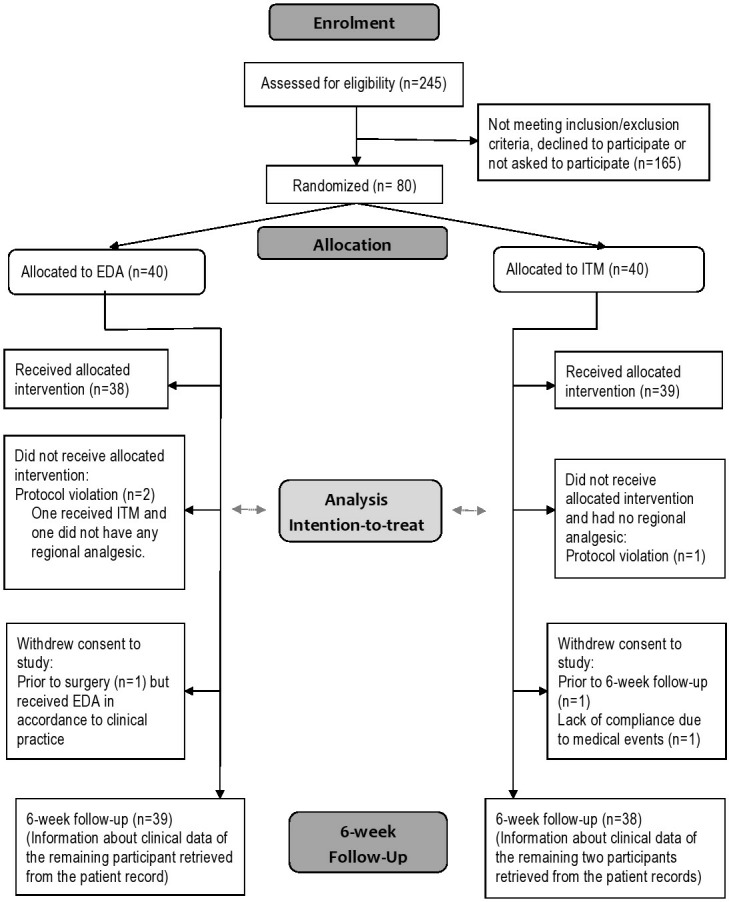

The description of the selection and the randomisation of the study population are presented in figure 1. Forty women were chosen to receive EDA and 40 to receive ITM. One woman in each group did not receive any regional analgesia and one woman had ITM instead of EDA based on a mistake by the attending anaesthesiologist.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart of participants in the study. EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia.

The descriptive and demographic data are shown in table 1. The clinical, surgical and anaesthesiological data are presented descriptively in table 2. None of the differences between the two treatment groups were considered to be of clinical significance.

Table 1.

Descriptive and demographic data of the study population

| EDA group n=40 |

ITM group n=40 |

|

| Age (years) | 59.0 (51.5–66.0) | 58.5 (54.0–62.5) |

| <50 years | 7 (17.5%) | 6 (15%) |

| 50–60 years | 16 (40%) | 20 (50%) |

| >60 years | 17 (42.5%) | 14 (35%) |

| Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) | 28.5 (24.7–31.2) | 27.8 (23.4–31.2) |

| BMI <25 kg/m2 | 11 (27.5%) | 13 (32.5%) |

| BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 15 (37.5%) | 15 (37.5%) |

| BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2 | 9 (22.5%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| BMI ≥35 kg/m2 | 5 (12.5%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| Parity | 2.0 (0–5) | 2.0 (0–4) |

| Smokers | 5 (12.5%) | 4 (10%) |

| Previous laparotomy | 17 (42.5%) | 17 (42.5%) |

| ASA classification | ||

| Class I | 15 (37.5%) | 15 (37.5%) |

| Class II | 25 (62.5%) | 25 (62.5%) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (10%) | 4 (10%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 (32.5%) | 12 (30%) |

| Pulmonary disease | 4 (10%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| Mild psychiatric disease | 6 (12.5%) | 4 (10%) |

| Previous malignancy | 4 (10%) | 2 (5%) |

| Current medication | ||

| Antidepressant/sedative | 8 (20%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| Analgesics | 7 (17.5%) | 12 (30%) |

| Indication for surgery | ||

| Proven/assumed gynecological malignancy | 16/24 (40%/60%) | 18/22 (45%/55%) |

Figures denote median and (IQR) or number and (percent).

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists risk classification; EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia.

Table 2.

Clinical surgical and anesthesiological data

| EDA group n=40 |

ITM group n=40 |

|

| Operation time (minutes) | 116 (80–151.5) | 139 (99.5–169) |

| Estimated per-operative blood loss (ml) | 100 (50–275) | 200 (50–250) |

| Extent of skin incision from superior edge of symphysis pubis to: | ||

| Umbilicus | 6 (15%) | 2 (5%) |

| Between umbilicus and processus xiphoideus | 17 (42.5%) | 21 (52.5%) |

| Processus xiphoideus | 17 (42.5%) | 17 (42.5%) |

| Extent of surgery* (no. of women) | ||

| Category I | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (2.5%) |

| Category II | 8 (20%) | 2 (5%) |

| Category III | 17 (42.5%) | 18 (45%) |

| Category IV | 8 (20%) | 14 (35%) |

| Category V | 6 (15%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| Tumour status at end of surgery (no. of women): | ||

| Macroscopically radical | 17 (63%) | 25 (76%) |

| Minimal disease | 3 (11%) | 5 (15%) |

| Bulky disease | 7 (26%) | 3 (9%) |

| Histopathological diagnosis: malignant/benign | 27/13 (67.5/32.5%) | 33/7 (82.5/17.5%) |

| Ovarian/fallopian tube/peritoneal cancer | 13 (32.5%) | 18 (45%) |

| Ovarian borderline cancer | 5 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Uterus carcinoma or sarcoma | 7 (17.5%) | 13 (32.5%) |

| Cervical cancer | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Appendix or sigmoideum cancer | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (5%) |

| Benign ovarian or uterine tumour | 13 (32.5%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| CAD at discharge (no. of women) | 3 (7.7%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| Premedication | ||

| Paracetamol (DDD) | 0.67 (0.44–0.67)) | 0.67 (0.67–0.67) |

| Morphine (mg) | 0 (0–0.75) | 0 (0–0) |

| Antiemetic, medication (no. of women) | 16 (57%) | 12 (43%) |

| Antiemetic, acupressure band (no. of women) | 22 (47%) | 25 (53%) |

| Anaesthetic drugs: | ||

| Propofol (mg) | 200 (160–240) | 200 (160–260) |

| Rocuronium bromid (mg) | 50 (40–60) | 50 (40–62.5) |

| Equivalent morphine dose (mg) | 30.5 (27.3–41.3) | 45.0 (40.0–50.0) |

| Paracetamol (mg) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Vasoactive treatment during anaesthesia | ||

| Ephedrine (mg) | 20 (7.5–25) | 20 (15–25) |

| Phenylephrine (μg) | 0 (0–1062) | 0 (0–1440) |

| Norepinephrine (μg) | 0 (0–21) | 0 (0–130) |

| Atropine (mg) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0.5) |

| Anaesthesia time (minutes) | 177.5 (142.5–202.5) | 200 (155–240) |

| Lowest body temperature during surgery (oC) | 35.7 (35.5–36.1) | 35.6 (35.4–35.9) |

| Body temperature at end of surgery (oC) | 36.1 (35.9–36.4) | 36.1 (35.7–36.3) |

| Time in PACU (hours) | 4.6 (4.2–5.6) | 5.7 (4.0–8.1) |

Figures denote number and (percent) or median and (IQR).

*Categories of extent of surgery: Category I, diagnostic surgery; Category II, resection of gynecologic organs only; Category III, resection of gynecologic organs, omentectomy and ±appendectomy; Category IV, as Category III+pelvic and/or paraaortic lymphadenectomy; Category V, as Category III±pelvic and/or paraaortic lymphadenectomy +resection of abdominal visceral organs.

CAD, transurethral or supra pubic indwelling catheter; DDD, defined daily dose; EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia; PACU, post anaesthesia care unit.

In 20%, the final diagnosis postoperatively was benign, most often showing a benign ovarian tumour or a large uterine fibroid. The benign diseases were evenly distributed between the two groups.

The LOS was statistically significantly shorter for the ITM group compared with the EDA group (median [IQR] 3.3 [3.1–4.8] vs 4.3 [3.4–5.2] days; p=0.01). The time to meet standardised discharge criteria was significantly shorter in the ITM group compared with the EDA group (median [IQR] 3.0 [2.5–3.5] vs 4.0 [3.5–4.5] days; p<0.001). Significantly more women in the ITM group were discharged from the hospital on the third day (25 women [62.5%] in the ITM group vs 12 [30%] in the EDA group, p=0.004).

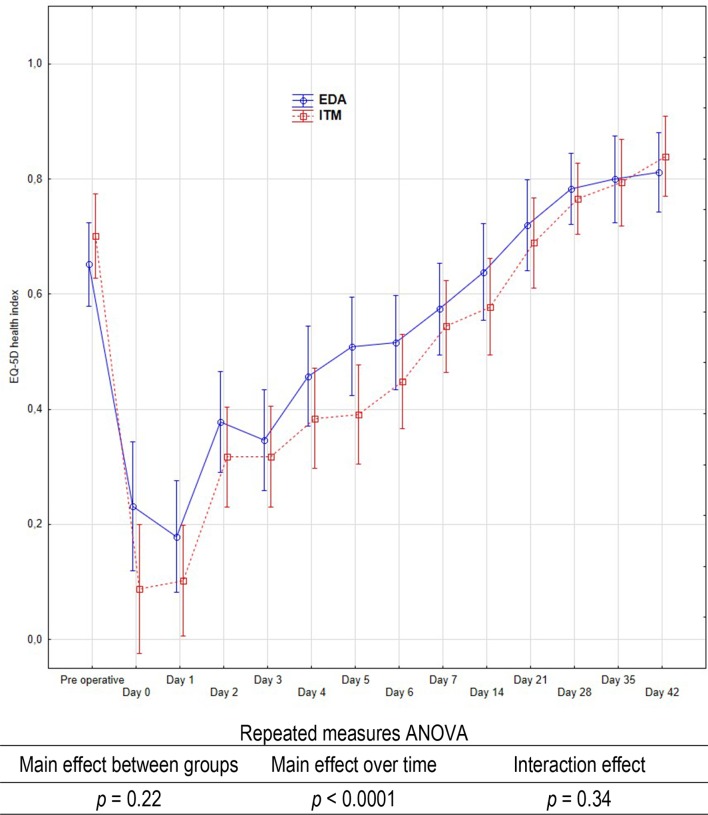

The QoL parameters as measured by the EQ-5D, day-by-day, presented no statistically significant difference in health index between the two groups (figure 2). Neither did the SF-36 show any statistically significant differences in the difference of baseline and 42 days assessments in any of the subscales or summary scores between the groups (table 3). The role physical and the physical component summary score had not recovered to baseline level in either of the two groups after 6 weeks, whereas the mental health and the mental component summary score showed a significant improvement after 6 weeks compared with the baseline assessment in the ITM group.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the EuroQol 5-dimension (EQ-5D) weighted health state index in relation to occasion of measurement. Plots represent means and bars represent 95% CI. Result of the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) from day 0–42 assessment is presented. No significant differences were observed in the EQ-5D health index between the two groups preoperatively. EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia.

Table 3.

SF-36 subscales and summary scores

| SF-36 subscales | Time lapse | Day 42 - Baseline | |||||

| Baseline | Day 42 | EDA | ITM | EDA vs ITM | |||

| EDA | ITM | EDA | ITM | P value* | P value* | P value† | |

| Physical functioning | 85 (63–95) | 80 (65–95) | 80 (65–95) | 83 (68–90) | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.69 |

| Role physical | 38 (0–100) | 63 (0–100) | 0 (0–13) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 | <0.0001 | 0.16 |

| Bodily pain | 51 (37–100) | 62 (47–84) | 58 (42–74) | 74 (52–84) | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| General health | 75 (57–85) | 72 (55–81) | 70(47–87) | 72 (59–81) | 0.10 | 0.65 | 0.10 |

| Vitality | 53 (40–75) | 53 (43–70) | 45 (33–68) | 55 (43–70) | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.20 |

| Social functioning | 75 (50–100) | 75 (56–81) | 75 (50–88) | 75 (50–75) | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.09 |

| Role emotional | 100 (0–100) | 100 (0–100) | 83 (0–100) | 100 (33–100) | 0.65 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Mental health | 76 (60–84) | 70 (60–80) | 78 (66–84) | 80 (66–86) | 0.54 | <0.01 | 0.13 |

| Physical component summary score | 44 (34–53) | 45 (34–53) | 39 (3444) | 38 (35–42) | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.41 |

| Mental component summary score | 46 (35–52) | 46 (35–51) | 49 (34–53) | 51 (39–55) | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

A high score represents a better health-related quality of life.

Figures indicate median (IQR).

No significant differences were observed in the subscales between the two groups at baseline (Mann-Whitney U-test).

*Wilcoxon matched pair tests.

†Mann-Whitney U test.

EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia; SF-36, Short Form–36 Health Survey.

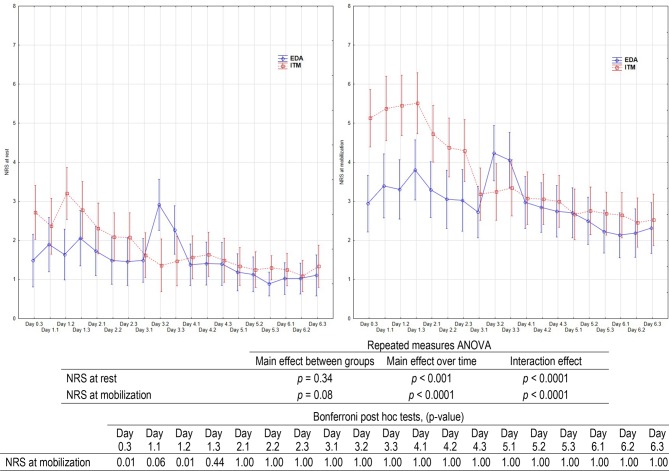

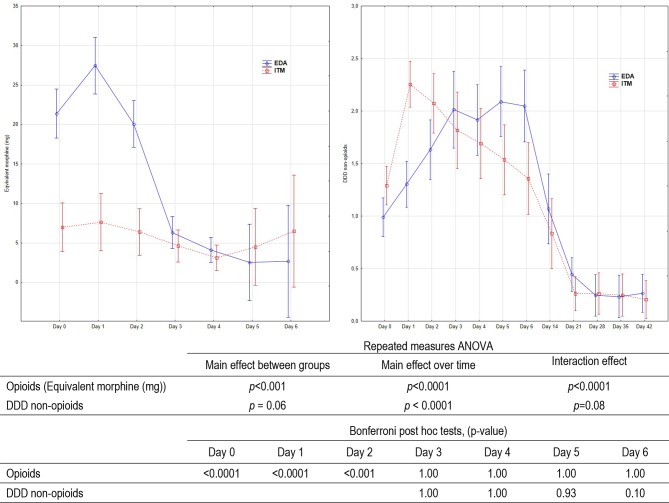

There was no significant difference in the overall assessment of pain (NRS) between the groups (figure 3). The two groups showed different patterns in the NRS ratings as indicated by the significant interaction effects. The post hoc tests showed that the NRS ratings were significantly higher in the ITM group during the first 2 days at mobilisation, whereas the EDA group scored significantly higher both at rest and at mobilisation on day 3 when the EDA catheter was removed. The ITM group had a significantly lower total consumption of opioids than the EDA group whereas the use of non-opioids was similar in the two groups (figure 4). The comparison of the non-opioids first started on day 3 when the protocol allowed equal administration of per oral analgesics for the EDA and ITM groups. Postoperatively, during day 0 to day 6 the total consumption of opioids were median (IQR) 20 mg (14–35 mg) in the ITM group compared with 81 mg (67–101 mg) in the EDA group (p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Assessment of pain by means of a 10 graded numeric rating scale (NRS) at rest and at mobilisation. Plots represent means and bars represent 95% CI. Results of the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc tests from day 0 to the day 6 are shown in the table below the diagrams. Assessments done from the evening of surgery and three times daily. Days 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3, respectively, represent the measurements performed in the morning, the afternoon and the evening on day 1. EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia.

Figure 4.

Consumption of analgesics after surgery in relation to occasion of measurement. Plots represent means and bars represent 95% CI. Results of the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc tests from day 0 to the day 6 assessment for equivalent morphine given and for day 3 to day 42 for defined daily dose (DDD) non-opioids are presented in the table below the diagram. EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia.

The EDA failed in four women (10%) and ITM analgesia in one (2.5%). These women had either a new EDA in the postanaesthesia care or received patient-controlled morphine intravenously. One accidental dural puncture occurred in the EDA group. No postdural puncture headache or anaesthesiological adverse effects were observed in either of the groups. The perioperative adverse events graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification in the two groups did not differ significantly (p=0.31) as shown in table 4.

Table 4.

The Clavien-Dindo classification of adverse events (contracted form) within the study period of 6 weeks

| EDA group (n=40) | ITM group (n=40) | |

| No complications | 19 (47.5) | 19 (47.5) |

| Grade I | 13 (32.5) | 8 (20.0) |

| Grade II | 6 (15.0) | 6 (15.0) |

| Grade III | 1 (2.5) | 6 (15.0) |

| Grade IV | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) |

Figures denote number and (percent).

Grade I: Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacological treatment or surgical, endoscopic and radiological interventions. Allowed therapeutic regimens are: drugs as antiemetics, antipyretics, analgetics, diuretics and electrolytes and physiotherapy. This grade also includes wound infections opened at the bedside.

Grade II: Requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than such allowed for grade I complications. Blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition are also included.

Grade III: Requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention

Grade IV: Life-threatening complication requiring intermediate care/intensive care unit management

P=0.31; χ2 for trends (df=4).

EDA, epidural analgesia; ITM, intrathecal morphine analgesia.

Discussion

The study showed that a single dose of intrathecal morphine used as postoperative analgesia compared with epidural analgesia gives advantages in abdominal gynaecological cancer surgery in regard to the length of hospital stay, the time to meet the standardised discharge criteria and lower consumption of opioids postoperatively. A substantially higher proportion of women with ITM was discharged on the third postoperative day with an evenly reported health-related QoL and assessment of pain as women with EDA. A key point of an ERAS protocol is simplicity and a single intrathecal injection is simpler than a continuous epidural requiring ongoing management and monitoring. We regard ITM as a quality improvement from the perspective of both the patients and the healthcare.

The strengths of this trial are the randomised design, the unanimous ERAS and postoperative surveillance of the patients in the gynaecological ward, the assessment of pain at rest and during mobilisation and the active use of rescue analgesics on demand. For obvious reasons, the interventions could not be blinded for the participants or the staff. This might be a source of bias, but we believe that the potential influence of such bias will be limited and unavoidable in the study design used. A limitation for generalisation of the results is the single-centre design. The ERAS concept is well established in daily clinical work and therefore the results can only be generalised to facilities with similar clinical standards and only to units that manage patients with regional analgesia. The two methods of regional analgesia may not be comparable in giving potentially equivalent analgesia with the dosage and preparation used. However, our objective was to compare the two analgesic methods in a clinical context, not to find the appropriate doses or types of analgesic agent for each method. Therefore, we selected conventional doses of the medications.

The use of intrathecal opioids requires close monitoring of sedation and respiratory rate for 12 hours. The nurses on the gynaecological ward were educated regarding complications after ITM with special regard to late respiratory depression and the surveillance followed strict national recommendations. Intrathecal morphine is used in approximately two-thirds of Swedish gynaecological units in connection with abdominal hysterectomy having a continued observation on the regular gynaecological ward after an initial period of 2–6 hours in a postoperative care unit.24 The intrathecal morphine dose 0.2 mg was chosen with the purpose of giving adequate analgesia at a risk of respiratory depression that equals systemic opioid analgesia.25 Following abdominal hysterectomy, there is no benefit from increasing the morphine dose over 0.2 mg.26 The α-agonist clonidine possesses an antinociceptive effect from receptors located in the central nervous system. The addition of clonidine to intrathecal opioids further prolongs postoperative analgesia.10

The de facto duration of hospital stay was shorter in the ITM group. A reduction of hospital stay with 1 day has clinical relevance for both the patient and the healthcare system. A similar short LOS has recently been reported from other ERAS programmes for gynaecological cancer.27–29 Wijk et al27 used an analgesic regimen based on oral paracetamol and diclofenac and over 90% of the patients did not need systemic opioids from the day after surgery. Like our study, they used standardised discharge criteria. It is important to analyse when discharge criteria are fulfilled, as they are robust and generalisable. The length of hospital stay is often influenced by context-specific social factors.

In this study, we compared two multimodal analgesic regimens considered clinically relevant. For that reason, we aimed to make each regimen as optimal as possible. As a consequence, there were differences in non-opioids as well as opioid regimens until the epidural catheter was removed. Only rescue opioids were equal for both groups. Thus, the aim was not to compare the intrathecal and the epidural routes per se.

Multimodal analgesic regime minimising opioid use has been shown to enhance recovery.2 30 ITM has become a well-documented component in several ERAS protocols29 31–34 and a protocol for a systematic review of ITM in abdominal and thoracic surgery patients has recently been published.35 Despite the higher rating of NRS at mobilisation during the first few days in the ITM group, the consumption of opioids was nearly three times lower in the same time period compared with the EDA group, and the QoL index did not differ between the groups. This may imply that the women in the ITM group were as satisfied as the EDA group with their pain management, and the difference in NRS rating at mobilisation was less clinically significant. The study included only ASA class I–II patients. For patients with more severe comorbidity, the EDA regimen could be favourable as it offers a better early analgesia that especially patients at risk for complications could benefit from. A study on abdominal hysterectomy for endometrial cancer showed that women without EDA ceased opioid analgesia earlier than those women who had an EDA,36 indicating a possible overuse of opioids in EDA. An earlier removal of the EDA catheter, for example after 48 hours, is a possible development of the EDA regimen. Prior to this trial, the standard praxis in our department was removal of the EDA catheter on the third day. Consequently, we studied the ITM against this regime. The difference in DDD of non-opioids seen until the third postoperative day was due to the protocol demand and the clinical routine in the hospital that diclofenac was not allowed in the EDA group until the EDA catheter was removed. The uneven use of diclofenac in the groups during the first three postoperative days may be seen as a weakness of the study. However, the DDD of non-opioids raised from day 1 to day 3 in the EDA group by using diclofenac in some patients against the study protocol and the clinical routines in the department. It is therefore less likely that the difference in DDD of non-opioids can explain the significant difference in opioids. In spite of the addition of diclofenac and consequently an increased DDD on the third postoperative day, the women in the EDA group rated the NRS at rest and at mobilisation higher than the ITM women. Our EDA regimen, including complementary analgesics, was obviously not optimal in preventing breakthrough pain in connection with terminating the epidural infusion. The opioid sparing effect of ITM has been demonstrated in a study analysing the first 48 postoperative hours.37 Our study might indicate an even longer benefit.

In order to increase the patient-oriented focus on recovery, we used two generic QoL forms to assess the patient-reported outcome of the health status. The EQ-5D was used to determine the short-term recovery day-by-day, whereas the SF-36 was used for a longer-term assessment. The short-term recovery in QoL did not seem to differ between the two regimes but at the longer term, the ITM seemed to give more pronounced advantages than EDA in the recovery of the mental health. The clinical importance of this remains unclear and merits further exploration. To the best of our knowledge, there is no condition-specific patient-reported outcome form for our patient group. Although there is no evidence of content validity for the EQ-5D or SF-36 for the specific patient group in this study, they are widely used and allow comparisons with population norms. A new form of the EQ-5D, the 5-level version (EQ-5D-5L), has been developed with the aim to better capture smaller health changes.38 At the time of the study, there was no Swedish value set available for EQ-5D-5L.

Severe complications after EDA and ITM are rare but still the indication for the regional analgesia should always be considered individually. In this trial, no severe complications attributed to the regional analgesia occurred and the adverse events seemed to be equally distributed between the groups. However, the trial was not powered to detect a statistical difference in adverse events.

In conclusion, ITM given in an ERAS programme seems to be safe, simple to administer and effective as postoperative analgesia and gives quality advantages concerning the postoperative recovery in gynaecological abdominal cancer surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research nurses Åsa Rydmark Kersley, Linda Shosholli and Gunilla Gagnö are thanked for their invaluable dedicated work and support during the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: PK, NBW and LN designed and conducted the study. PK performed the statistically analyses. PK, OB, NBW and LN undertook the initial interpretation of the data, which was followed by discussions with all the authors. PK, OB and LN drafted the initial version of the manuscript, followed by a critical revision process for intellectual content involving all authors. All authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript before submission. All authors agree to be accountable for the accuracy of any part of the work.

Funding: The study was supported financially by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine (SLS-404711), the Medical Research Council of South-east Sweden (FORSS-8685), Linköping University and the Region Östergötland (LIO-356191, LIO-441781).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Board of Linköping University (D.nr. 2013/185-31, approval date 29 August 2013), the Swedish Medical Products Agency (Eu-nr. 2013-001873-25; D.nr. 5.1-2013-50334, approval date 1 August 2013) and monitored by an independent monitor.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are avaiable on request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Nygren J, Thacker J, Carli F, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr 2012;31:801–16. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feldheiser A, Aziz O, Baldini G, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) for gastrointestinal surgery, part 2: consensus statement for anaesthesia practice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016;60:289–334. 10.1111/aas.12651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devys JM, Mora A, Plaud B, et al. Intrathecal + PCA morphine improves analgesia during the first 24 hr after major abdominal surgery compared to PCA alone. Can J Anaesth 2003;50:355–61. 10.1007/BF03021032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrieu G, Roth B, Ousmane L, et al. The efficacy of intrathecal morphine with or without clonidine for postoperative analgesia after radical prostatectomy. Anesth Analg 2009;108:1954–7. 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a30182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakowska M, Docherty E, Linscott D, et al. A change in practice from epidural to intrathecal morphine analgesia for hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery. World J Surg 2009;33:1802–8. 10.1007/s00268-009-0131-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bujedo BM, Santos SG, Azpiazu AU. A review of epidural and intrathecal opioids used in the management of postoperative pain. J Opioid Manag 2012;8:177–92. 10.5055/jom.2012.0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borendal Wodlin N, Nilsson L, Kjølhede P. GASPI study group. The impact of mode of anaesthesia on postoperative recovery from fast-track abdominal hysterectomy: a randomised clinical trial. BJOG 2011;118:299–308. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kroon UB, Rådström M, Hjelthe C, et al. Fast-track hysterectomy: a randomised, controlled study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010;151:203–7. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Engelman E, Marsala C. Efficacy of adding clonidine to intrathecal morphine in acute postoperative pain: meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:21–7. 10.1093/bja/aes344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sites BD, Beach M, Biggs R, et al. Intrathecal clonidine added to a bupivacaine-morphine spinal anesthetic improves postoperative analgesia for total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2003;96:1083–8. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000055651.24073.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kara I, Apiliogullari S, Oc B, et al. The effects of intrathecal morphine on patient-controlled analgesia, morphine consumption, postoperative pain and satisfaction scores in patients undergoing gynaecological oncological surgery. J Int Med Res 2012;40:666–72. 10.1177/147323001204000229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Pietri L, Siniscalchi A, Reggiani A, et al. The use of intrathecal morphine for postoperative pain relief after liver resection: a comparison with epidural analgesia. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1157–63. 10.1213/01.ane.0000198567.85040.ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koea JB, Young Y, Gunn K. Fast track liver resection: the effect of a comprehensive care package and analgesia with single dose intrathecal morphine with gabapentin or continuous epidural analgesia. HPB Surgery 2009;2009:1–8. 10.1155/2009/271986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vercauteren M, Vereecken K, La Malfa M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of analgesia after Caesarean section. A comparison of intrathecal morphine and epidural PCA. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002;46:85–9. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Good Clinical Practice. International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. http://ichgcp.net/ (Accessed 28 Apr 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Allocation. Simple Interactive Statistical Analysis. http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/ (Accessed 28 Apr 2018).

- 17. Svensk Förening för Anestesi och Intensivvård. Postoperative analgesia (In Swedish). https://sfai.se/riktlinje/medicinska-rad-och-riktlinjer/anestesi/postoperativ-smartlindring/ (Accessed 28 Apr 2018).

- 18. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index. 2017. Available online at https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (Accessed 28 Apr 2018).

- 19. Loper KA, Ready LB, Downey M, et al. Epidural and intravenous fentanyl infusions are clinically equivalent after knee surgery. Anesth Analg 1990;70:72–5. 10.1213/00000539-199001000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e58–68. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70040-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications. A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:206–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey--I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1349–58. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00125-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hein A, Gillis-Haegerstrand C, Jakobsson JG. Neuraxial opioids as analgesia in labour, caesarean section and hysterectomy: a questionnaire survey in Sweden. F1000Res 2017;6:133 10.12688/f1000research.10705.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gehling M, Tryba M. Risks and side-effects of intrathecal morphine combined with spinal anaesthesia: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2009;64:643–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05817.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hein A, Rösblad P, Gillis-Haegerstrand C, et al. Low dose intrathecal morphine effects on post-hysterectomy pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012;56:102–9. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wijk L, Franzén K, Ljungqvist O, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in abdominal hysterectomies for malignant versus benign disease. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2016;81:461–7. 10.1159/000443396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carter J. Fast-track surgery in gynaecology and gynaecologic oncology: a review of a rolling clinical audit. ISRN Surg 2012;2012:1–19. 10.5402/2012/368014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dickson EL, Stockwell E, Geller MA, et al. Enhanced recovery program and length of stay after laparotomy on a gynecologic oncology service: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:355–62. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nelson G, Altman AD, Nick A, et al. Guidelines for postoperative care in gynecologic/oncology surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations--Part II. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:323–32. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khalil A, Ganesh S, Hughes C, et al. Evaluation of the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in living liver donors. Clin Transplant 2018;32:e13342 10.1111/ctr.13342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koning MV, Teunissen AJW, van der Harst E, et al. Intrathecal morphine for laparoscopic segmental colonic resection as part of an enhanced recovery protocol: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018;43:166–73. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Helander EM, Webb MP, Bias M, et al. Use of regional anesthesia techniques: analysis of institutional enhanced recovery after surgery protocols for colorectal surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2017;27:898–902. 10.1089/lap.2017.0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Virlos I, Clements D, Beynon J, et al. Short-term outcomes with intrathecal versus epidural analgesia in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2010;97:1401–6. 10.1002/bjs.7127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pitre L, Garbee D, Tipton J, et al. Effects of preoperative intrathecal morphine on postoperative intravenous morphine dosage: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2018;16:867–70. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Belavy D, Janda M, Baker J, et al. Epidural analgesia is associated with an increased incidence of postoperative complications in patients requiring an abdominal hysterectomy for early stage endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2013;131:423–9. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Massicotte L, Chalaoui KD, Beaulieu D, et al. Comparison of spinal anesthesia with general anesthesia on morphine requirement after abdominal hysterectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:641–7. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life: An EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ 2018;27:7–22. 10.1002/hec.3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.