Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs are being used worldwide in consumer products and industrial applications.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs are being used worldwide in consumer products and industrial applications.

Abstract

Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs are being used worldwide in consumer products and industrial applications. Based on predefined pathways, this study synthesized and characterized the nanostructures of ZnO NPs. The genotoxic effects of these nanomaterials were evaluated using a short-term in vivo bioassay, the somatic mutation and recombination test (SMART) in Drosophila melanogaster. In addition, a systems biology approach was used to search for known and predicted interaction networks between ZnO and proteins. The results observed in this study after in vivo exposure indicate that ZnO NPs are genotoxic and that homologous recombination (HR) was the main mechanism inducing loss of heterozygosis in the somatic cells of D. melanogaster. The results of in silico analysis indicated that ZnO is associated with the nuclear factor-kappa-beta (NFKB) protein family. In accordance with this model, ZnO exposure decreases the levels of NFKB inhibitory protein in the cell, consequently increasing NFKB dimers in the nucleus and inducing DNA double strand breaks (DSB) repair via HR. This excess level of HR can be observed in the SMART results. Assessing the mutagenic/recombinagenic effect of nanomaterials is essential in the development of strategies to protect human and environmental integrity.

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology has a wide spectrum of applications in various sectors, such as energy production and in the electronics, food, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, optical, remediation, and miscellaneous materials industries. However, this wide application range varies due to the involvement of different areas of knowledge, including chemistry, physics, engineering, pharmaceutics, biology, and medicine. For this reason, nanotechnology is characterized as a multidisciplinary field. With the increasing stimulus to the development, production, and large-scale application of nanomaterials, the industry has focused on making new nanoparticles, which have been tested and used in a range of products, leading to increased human exposure to nanomaterials and the dispersion of nanoparticles in the environment.1–3

Zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles are being used worldwide in consumer products and industrial applications. ZnO NPs have a high refractive index and brightness, and are regularly used as whitening pigments. The specific properties of ZnO NPs are interesting in terms of the development of commercial products such as paints and bleaching agents in food products. Due to their structure, suspensions of ZnO NPs are widely used in cosmetics, skin care, and sun protection products.4

Research has focused on the cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of ZnO NPs in eukaryotic cells.5,6 Sharma et al.7 investigated the genotoxic potential of ZnO NPs in human liver cells HepG2 using the comet assay. The results pointed to the relationship between genotoxicity and exposure time. Also, ZnO NPs delayed the development of Danio rerio embryos, causing tissue damage and decreasing survival and hatching. Using different aquatic organisms, another study discussed the toxic effects of exposure to ZnO NPs on Vibrio fischeri, Daphnia magna, and Tamnocephalus platyuru.8 Although the mechanisms behind the properties of ZnO NPs are not fully understood, it was shown that ZnO NPs could increase the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing genotoxicity and cell death.7,9 Therefore, in order to determine the real effects of ZnO NPs on organisms, in vivo studies are necessary because the complexity of living organisms (various interactions, hormonal and enzymatic effects, and repair mechanisms) will influence the response to the compound being evaluated. Importantly, the results of these in vivo studies should be complemented with cell tests.

The present study evaluated the genotoxicity of ZnO NPs using the somatic mutation and recombination test (SMART) in the somatic cells of Drosophila melanogaster.10 The test affords to investigate the loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of marker genes expressed as somatic mutation and recombination after the exposure of third-instar larvae to ZnO NPs. Due to the homology of genetic sequences, D. melanogaster, the fruit fly, is the invertebrate model organism that is most closely related to humans.11 The high sensitivity to toxic substances makes D. melanogaster an excellent model organism for the assessment of NP toxicity,12,13 which is why it is used as a replacement for vertebrate species in toxicity assays.14 In addition, we used a systems biology approach in order to detect the known and predicted interaction networks between ZnO and proteins.

2. Materials and methods

Nanoparticle synthesis and structural characterization

The raw materials in this experiment were all of laboratory grade. The process of preparing nanoparticles (NPs) from collagen–metal interactions (sol–gel protein method) can be divided into three stages, which are illustrated as follows:15

i Solution preparation. Collagen (2.5 g) is dissolved in water (40 mL) (Milli-Q) on a hotplate at 45 °C with vigorous stirring over 30 min, then zinc nitrate (1 g) is gradually added to the solution, and the mixture is stirred for 20 min.

ii Drying. The solution was dried at 60 °C for 48 h.

iii Decomposition. The resin was then calcined for 3 h at 250 °C and ground. The powder is calcined for 6 h at 550 °C in order to obtain the NPs.

The structural characterization of powders was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Bragg–Brentano geometry in a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer operating with Cu-Kα radiation (1.54 Å) at 40 kV and 20 mA. The 2θ angle was scanned with 0.02° of steps and 5 s of integration time from 25° to 80°. Crystallite size was estimated using Scherrer's formula and Williamson–Hall analysis.16

Nanoparticles were solubilized in distilled water and sonicated to avoid aggregation.

The somatic mutation and recombination test (SMART) in Drosophila melanogaster

Two versions of the SMART were used: (i) standard (ST) cross: flr3/TM3, BdS females to mwh/mwh males and (ii) high bioactivation (HB) cross: ORR/ORR; flr3/TM3, BdS females to mwh/mwh males. Eggs from these two crosses were collected over 8 h on a standard medium enriched with baker's yeast supplemented with sucrose. After three days, the larvae were washed out of the vials and used for the treatments. Chronic treatments (48 h until pupation) were performed by adding equal batches of larvae (72 ± 4 h) from the ST and HB crosses to vials containing 1.5 g of Drosophila Instant Medium (Carolina Biological Supply Company, Burlington, NC, USA) plus 5 mL of fresh solutions of ZnO NP concentrations (0.075–2.4 mg mL–1) previously diluted in distilled water. In order to analyze the toxicity of ZnO NPs we performed a survival test, in which batches of 100 larvae were treated with different concentrations (0.075–2.4 mg mL–1) of NPs. The number of surviving flies was counted and the NP concentrations should allow at least 50% of survival to qualify for the genotoxicity assay. The NPs were tested in triplicate in two independent experiments. A negative control was always included.

Approximately 10–12 days after the treatment, the emerging adult flies were collected and conserved in 70% ethanol. The ST and HB crosses produced two types of progeny that were distinguished phenotypically based on the Bds marker: (i) trans-heterozygous flies for the recessive wing-cell markers multiple wing hair (mwh) and flare (flr3) and (ii) heterozygous flies for a balancer chromosome with large inversions on chromosome 3 (TM3). Wings of five females and five males of the two phenotypes were mounted on slides and scored under a microscope at 400× magnification for the occurrence of spots. Induced LOH in the marker-heterozygous genotype leads to two types of mutant clones: (i) single spots, either mwh or flr3, which result from point mutation, chromosome aberration and/or somatic recombination, and (ii) twin spots, consisting of both mwh and flr3 sub-clones, which originate exclusively from somatic recombination.10 In flies with the balancer-heterozygous genotype, mwh spots reflect predominantly somatic point mutation and chromosome aberration, since somatic recombination involving the balancer chromosome and its structurally normal homologue is a nonviable event. By comparing the frequencies of these two genotypes it was possible to quantify the recombinagenic and mutagenic activities of ZnO NPs.17

The frequency of each type of spot (small single, large single or twin) and the total frequency of spots per fly for each treatment were compared pair-wise with the frequency of the negative concurrent control (distilled water) using the Kastenbaum–Bowman test (P < 0.05).18 Because of the weak expression of the flr3 marker in small clones and its lethality in large clones of mutant cells, only the mwh clones (mwh single and mwh twin spots) were used to calculate clone formation frequencies per 105 cells (n/NC). These values are then employed to estimate the contribution of recombination (R) and mutation (M) to the incidence of total mutant spots per fly in trans-heterozygous genotypes, according to the formulae: R = 1 – [(n/NC in mwh/TM3 flies)/(n/NC in mwh/flr3 flies)] × 100 and M = 100 – R. The mwh clone frequency per fly makes it possible to estimate the induction frequency per cell and per cell division. An appropriate estimation of induction frequency is obtained when the mwh clones per fly frequency is divided by the number of cells (48 800) present in both wings. We used 48 800 (24 400 per wing) instead of 60 000 cells (2 × 30 000—considering both wings), because not every cell in a wing is examined in screening for wing spots; there are ∼24 400 cells in the wing area inspected for spots.19

Systems biology analysis

In order to search for the known and predicted interactions between chemicals and proteins as well as proteins and proteins, online search tools STITCH 5.020 [; http://stitch.embl.de/] and STRING 10.021 [; http://string-db.org/] were used, respectively. In these two online search tools, the interaction network between zinc oxide (ZnO) and proteins was downloaded based on the following parameters: no more than 50 interactions, a high confidence score (0.400), and a network depth equal to 2. All of the active prediction methods were enabled, excluding text mining. A search for Homo sapiens and D. melanogaster as model organisms was carried out in STITCH 5.0, but no prediction about ZnO and D. melanogaster proteins is available. Then, the different networks generated from these screening for H. sapiens were imported and combined employing the union function of the Cytoscape 3.422 plugin Merge Network. Based on network topology, modules/clusters (densely connected regions) that suggest functional protein complexes were analyzed with the Cytoscape 3.4 plugin Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE).23 For this, the parameters used were: loops included; degree cutoff 2; deletion of single connected nodes from cluster (haircut option enabled); expansion of cluster by one neighbor shell allowed (fluff option enabled); node density cutoff 0.1; node score cutoff 0.2; kcore 2; and maximum depth of network 100. Gene ontology (GO) (concepts/classes used to describe the gene function) in the clusters generated from MCODE was analyzed by Cytoscape 3.4 plugin Biological Network Gene Ontology (BiNGO).24 The degree of functional enrichment for a given cluster and category was quantitatively computed (P value) by hypergeometric distribution, and multiple test correction was also assessed by applying the false discovery rate (FDR) algorithm25 which was fully implemented using the BiNGO software with a significance level of P < 0.05. Next, node centrality analysis was computed using Cytoscape 3.4 plugin Centiscape 2.126 to identify which nodes (proteins) have a central position within the networks. Centralities implemented were degree and betweenness to undirected networks, nodes with a relatively higher degree were termed hubs, and nodes with higher betweenness were named bottlenecks. Hub nodes interact with many other nodes in the network and thus often occupy central positions in the network. By contrast, a bottleneck node does not necessarily have many interactions, but it has a high degree of betweenness centrality, meaning that it will often be a linker between different clusters.27,28 Therefore, a node hub-bottleneck (N-HB) can be considered a key regulator of biological processes and essential for the successful transfer of information through the network, where N-HB perturbations are more likely to cause network fragmentation.

3. Results

Characterization of ZnO NPs

The XRD pattern of ZnO NPs is shown in Fig. 1. Well-defined and broader diffraction peaks, all corresponding to the characteristic crystallographic planes of standard polycrystalline ZnO with a hexagonal wurtzite phase, were detected (JCPDS: 36-1451). Broadening of the peaks indicated the nanocrystalline nature of ZnO particles. The value of the mean crystallite size, obtained from the different models, was estimated to be 27 ± 2 nm in diameter.

Fig. 1. X-ray powder diffractogram of ZnO NPs. The characteristic diffracted directions (planes in the Miller indices) are indexed.

The images were obtained by TEM (JEM 1200 EXll) and analyzed using the ImageJ 1.46r software. The TEM image showed irregular-shaped particles with rounded edges and an average size of 86.73 ± 43.46 nm (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B shows the particle size distribution of the sample used in the study. The particle size distribution was estimated from the analysis of the images obtained by TEM for 170 randomly drawn particles. The diagram shows that the particle size ranged from 30 to 200 nm, with particles between 50 and 80 nm predominating.

Fig. 2. A typical TEM image of ZnO NPs (A). Size frequency of ZnO NPs as observed from the TEM image (B).

Genotoxicity of ZnO NPs

The results of the survival test demonstrated that ZnO NP concentrations of 1.8 and 2.4 mg mL–1 induced more than 50% of toxicity to third instar larvae of D. melanogaster (Fig. 3). Thus, the concentrations used in the genotoxicity tests ranged from 0.075 to 1.2 mg mL–1.

Fig. 3. Survival percentage after the exposure of third instar larvae of D. melanogaster to different concentrations (0.075–2.4 mg mL–1) of ZnO NPs. NC = negative control.

Tables 1 and 2 show the results of chronic exposure of ST and HB larvae to ZnO NPs. Frequencies of different classes of spots, small single, large, twin, and total spots are shown. The frequency values of mutant spots after the exposure of ST and HB larvae to distilled water (negative control) were similar to the values obtained in previous studies using the SMART.29,30 In addition, positive control (urethane 20 mM) induced significant increases in the frequencies of all spot categories, and the values for the HB cross were significantly higher when compared with the values observed for the ST cross. In the cases of positive statistical diagnosis, the (mwh/TM3) flies were also scored to measure the contribution of mutagenic and recombinagenic events to the final genotoxicity.

Table 1. Fly spot data obtained after the exposure of trans (mwh/flr3) and balancer heterozygous (mwh/TM3) larvae of standard (ST) cross of D. melanogaster to ZnO NPs.

| Genotypes | Treatments (mg mL–1) | No. of flies (N) | Spots per fly (number of spots)/statistical diagnosis

a

|

Spots with mwh clone c (n) | Frequency of clone formation per 105 cells e (control corrected) d , f | Recombination g (%) | Mutation g (%) | |||

| Small single spots b (1–2 cell) (m = 2) | Large single spots b (>2 cell) (m = 5) | Twin spots (m = 5) | Total spots (m = 2) | |||||||

| mwh/flr3 | PC | 10 | 6.50(65)+ | 1.00(10)+ | 0.30(03) i | 7.80(78)+ | 73 | 14.34 [12.95] | ||

| NC | 60 | 0.78(47) | 0.02(01) | 0.02(01) | 0.82(49) | 43 | 1.47 | |||

| 0.075 | 60 | 0.61(37)– | 0.17(10)+ | 0.03(02) i | 0.82(49)– | 48 | 1.64 [0.17] | |||

| 0.15 | 60 | 0.70(42)– | 0.18(11)+ | 0.03(02) i | 0.92(55)– | 53 | 1.81 [0.34] | |||

| 0.3 | 60 | 1.48(89)+ | 0.08(05) i | 0.00(00) i | 1.57(94)+ | 91 | 3.11 [1.64] | 97.50 | 2.50 | |

| 0.6 | 60 | 1.30(78)+ | 0.10(06) i | 0.02(01) i | 1.42(85)+ | 85 | 2.90 [1.43] | 91.43 | 8.57 | |

| 1.2 | 60 | 2.00(120)+ | 0.02(01) i | 0.00(00) i | 2.02(121)+ | 118 | 4.03 [2.56] | 100.00 | 0.00 | |

| mwh/TM3 | NC | 50 | 0.30(15) | 0.00(00) i | h | 0.30(15) | 15 | 0.61 | ||

| 0.3 | 50 | 0.32(16) i | 0.00(00) i | 0.32(16) i | 16 | 0.66 [0.04] | ||||

| 0.6 | 50 | 0.36(18) i | 0.00(00) i | 0.36(18) i | 18 | 0.74 [0.12] | ||||

| 1.2 | 50 | 0.28(14)– | 0.02(01) i | 0.30(15)– | 15 | 0.61 [0.00] | ||||

aStatistical diagnosis according to Frei and Wurgler:31 +: positive; i: inconclusive; –negative; M: multiplication factor. Significance levels α = β = 0.05.

bIncluding individual rare flr3 spots.

cConsidering mwh spots of single mwh and twin spots.

dNumbers between keys are induction frequencies corrected for spontaneous incidence estimated from negative controls.

eFor the calculation see Andrade et al.19

f C = 48 800, i.e., the approximate number of cells examined per fly.

gThe percentage of recombination (R) was calculated according to Frei and Würgler:17R = 1 – [(n/NC × in flies mwh/TM3)/(n/NC × in flies mwh/flr3)] × 100. Control corrected frequencies were used for these calculations.

hOnly mwh single spots can be observed in mwh/TM3 heterozygotes as the balancer chromosome TM3 does not carry the flr3 mutation. NC – negative control, PC – positive control, urethane 20 mM.

Table 2. Fly spot data obtained after the exposure of trans-heterozygous (mwh/flr3) larvae of high bioactivation (HB) cross of D. melanogaster to ZnO NPs.

| Genotype | Treatments (mg mL–1) | No. of flies (N) | Spots per fly (number of spots)/statistical diagnosis

a

|

Spots with mwh clone c (n) | Frequency of clone formation per 105 cells e (control corrected) d , f | |||

| Small single spots b (1–2 cell) (m = 2) | Large single spots b (>2 cell) (m = 5) | Twin spots (m = 5) | Total spots (m = 2) | |||||

| mwh/flr3 | PC | 10 | 20.0(200)+ | 9.0(90)+ | 4.50(45)+ | 33.50(335)+ | 320 | 65.57 (63.44) |

| NC | 50 | 0.78(39) | 0.12(06) | 0.06(03) i | 0.96(48) | 46 | 1.89 | |

| 0.075 | 50 | 0.68(34)– | 0.10(05) i | 0.06(03) i | 0.84(42)– | 40 | 1.64 [–0.25] | |

| 0.15 | 50 | 0.84(42)– | 0.10(05) i | 0.04(02) i | 0.98(49)– | 48 | 1.97 [0.08] | |

| 0.3 | 50 | 0.68(34)– | 0.02(01)– | 0.00(00) - | 0.70(35)– | 35 | 1.43 [–0.45] | |

| 0.6 | 50 | 0.90(45)– | 0.12(06) i | 0.02(01) i | 1.04(52)– | 50 | 2.05 [0.16] | |

| 1.2 | 50 | 0.72(36)– | 0.10(05) i | 0.08(04) i | 0.90(45)– | 44 | 1.80 [–0.08] | |

aStatistical diagnosis according to Frei and Wurgler:31 +: positive; i: inconclusive; –negative; M: multiplication factor. Significance levels α = β = 0.05.

bIncluding individual rare flr3 spots.

cConsidering mwh spots of single mwh and twin spots.

dNumbers between keys are induction frequencies corrected for spontaneous incidence estimated from negative controls.

eFor the calculation, see Andrade et al.19

f C = 48 800, i.e., the approximate number of cells examined per fly. NC – negative control. PC – positive control, urethane 20 mM.

Considering the trans-heterozygous (mwh/flr3) genotype in the ST cross, the three top concentrations of ZnO NPs used (0.3, 0.6, and 1.2 mg mL–1) induced significant differences in the total spot frequencies, compared to the negative control group. This difference reflects the positive results observed in the small single spots category. No positive diagnosis was observed in the balancer heterozygous flies after exposure to ZnO NPs. Additionally, recombination events were the main mechanism inducing lesions in ST larvae exposed to ZnO NPs. The percentage of recombination after exposure to ZnO NP concentrations of 0.3, 0.6 and 1.2 mg mL–1 was 97.5, 91.4 and 100%, respectively. The HB cross results showed no positive results in the total spot category (Table 2).

In silico analysis of ZnO

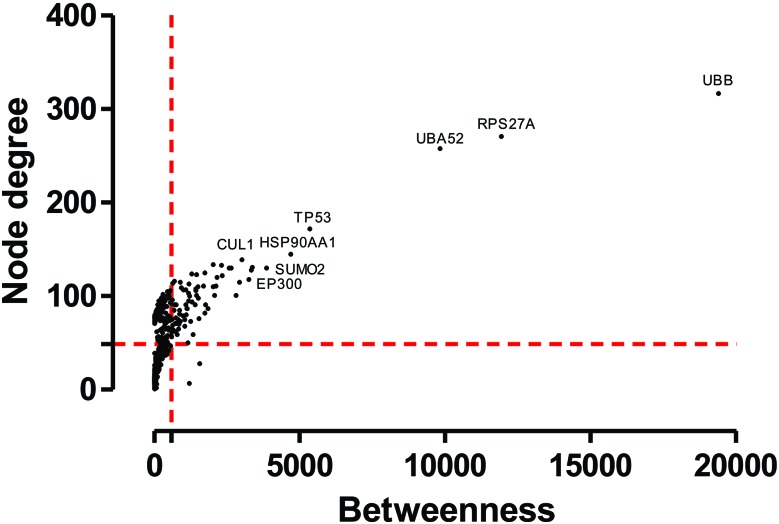

For the purposes of building a protein interaction network with ZnO, online search tools with available data about the physical and functional interactions between different human proteins and small compounds were used, resulting in a network composed of 591 nodes and 14 538 edges (Fig. 4). The presence of clusters was evaluated to determine the network substructure with densely connected nodes and to elucidate the functionality of the protein groups. Modularity analyses afforded to visualize ten clusters above the cutoff score (data not shown). Next, GO analysis was carried out for all clusters, and it identified the biological processes associated with these protein modules (data not shown). Cluster 1 had the highest score (Table 3), presenting key biological processes such as: the ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, proteolysis involved in the cellular protein catabolic process, response to the DNA damage stimulus, signal transmission via the phosphorylation event, positive regulation of the I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB cascade, and response to oxidative stress and double-strand break repair. In this study, node degree and betweenness were the two centrality parameters analyzed. This analysis enabled checking of the proteins that make up the most relevant network (hub-bottlenecks). By applying the centrality plugin, it was possible to detect N-HB nodes; consequently, the major HB was identified in the network (Fig. 5). Among these HB nodes, the main proteins involved in ubiquitination mechanisms such as UBC, UBB, RPS27A, UBA52, SUMO2 and CUL1 (; http://www.genecards.org) were identified. Another key HB protein is NFKBIA, which is linked directly to ZnO, NFKB1 and NFKB2 (Fig. 4). These proteins of the NF-kappa-B complex are associated with cluster 1 bioprocesses (Table 3).

Fig. 4. The chemical–protein interacting network of zinc oxide with proteins of Homo sapiens. Zinc oxide is represented by dark grey nodes.

Table 3. Specific gene ontology classes derived from protein–protein interactions observed in cluster 1.

| GO biological process category | GO number | P-Value | Corrected P-value* | k a | f b | Proteins |

| Ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 6511 | 1.70 × 10–102 | 1.20 × 10–99 | 124 | 280 | UBE2D2; UBE2D3; CCNF; UBE2D1; UBE3A; FBXO22; PARK2; UBE2L3; PSMD8; CDC20; PSMD9; NUB1; PSMD6; PSMD7; PSMD4; PSMD5; CDH1; PSMD2; PSMD3; PSMD1; FBXO6; BTRC; FBXO7; SKP1; USP8; USP7; ANAPC7; FBXW7; FBXW11; FBXO2; USP2; UBE2E1; FBXO11; RBX1; CDC34; PSME3; PSME1; PSME2; ANAPC5; RBCK1; SQSTM1; PSMD10; CUL7; PSMD12; VCP; TSG101; PSMD11; CUL5; PSMD14; UBA6; PSMD13; CUL3; CUL2; CUL1; ANAPC11; CCNB1; C6; UBR5; HSPA5; UBE2B; SMURF1; UBE2C; CYLD; NPLOC4; UBE2S; MDM2; CDK1; UBE2N; FBXL5; UBE2 K; UBXN1; FAF1; ARRB2; UCHL1; HC3; USP47; RAD23A; UCHL3; RAD23B; UCHL5; DDB1; PSMA5; PSMA6; PSMA3; PSMA4; PSMA1; PSMA2; BIRC2; USP14; USP15; NEDD8; RCHY1; RNF4; PSMA7; PSMA8; PSMB6; PSMB7; PPP2CB; PSMB4; FZR1; PSMB5; PSMB2; PSMB3; PSMB1; USP1; BUB3; USP25; MAP3K1; USP9X; AMFR; WWP2; UBE2G2; CUL4A; PSMC5; ITCH; PSMC6; PSMC3; PSMC4; PSMC1; NEDD4; PSMC2; STUB1; TRIM32; CUL4B; |

| Proteolysis involved in cellular protein catabolic process | 51603 | 2.67 × 10–100 | 1.15 × 10–97 | 128 | 314 | UBE2D2; UBE2D3; CCNF; UBE2D1; UBE3A; FBXO22; PARK2; UBE2L3; PSMD8; CDC20; PSMD9; NUB1; PSMD6; PSMD7; PSMD4; PSMD5; CDH1; PSMD2; PSMD3; PSMD1; FBXO6; BTRC; FBXO7; SKP1; USP8; USP7; ANAPC7; FBXW7; FBXW11; FBXO2; USP2; UBE2E1; FBXO11; RBX1; CDC34; PSME3; PSME1; PSME2; ANAPC5; RBCK1; SQSTM1; PSMD10; CUL7; PSMD12; VCP; TSG101; PSMD11; CUL5; PSMD14; UBA6; PSMD13; CUL3; CUL2; CUL1; ANAPC11; CCNB1; C6; UBR5; HSPA5; UBE2B; SMURF1; UBE2C; NFKB1; CYLD; NPLOC4; UBE2S; MDM2; CDK1; UBE2N; FBXL5; UBE2 K; UBXN1; FAF1; ARRB2; UCHL1; CASP8; HC3; USP47; RAD23A; UCHL3; RAD23B; UCHL5; DDB1; PSMA5; PSMA6; PSMA3; PSMA4; PSMA1; PSMA2; TRAF6; BIRC2; USP14; USP15; NEDD8; RCHY1; RNF4; PSMA7; RELA; PSMA8; PSMB6; PSMB7; PPP2CB; PSMB4; FZR1; PSMB5; PSMB2; PSMB3; PSMB1; USP1; BUB3; USP25; MAP3K1; USP9X; AMFR; WWP2; UBE2G2; CUL4A; PSMC5; ITCH; PSMC6; PSMC3; PSMC4; PSMC1; NEDD4; PSMC2; STUB1; TRIM32; CUL4B |

| Response to a DNA damage stimulus | 6974 | 3.02 × 10–16 | 8.77 × 10–15 | 54 | 396 | CDKN1A; MCM7; UBE2D3; BRCA1; SUMO1; PTTG1; CCND1; CDH1; CASP3; CHEK1; UIMC1; FBXO6; IKBKG; TP63; POLH; PARP1; H2AFX; RAD23A; CSNK1E; RAD23B; RBX1; RNF168; DDB1; CCNA2; FANCD2; CRY2; UBE2V2; CRY1; TP53; VCP; PCNA; XIAP; BRCC3; FOXO3; ATXN3; FZR1; UBR5; RPS3; MAPK1; MAP2K6; FANCI; XRCC6; UBE2B; XRCC5; PLK1; PML; SOD1; CUL4A; BCL3; CDK1; UBE2N;RAD18; CUL4B; TP73 |

| Signal transmission via the phosphorylation event | 23014 | 2.42 × 10–15 | 6.38 × 10–14 | 50 | 362 | IRS1; LRRK2; FAF1; IKBKB; TBK1;PPP2R1A; AKT1; EP300; IKBKG; PRKACA; MAP3K7; MAP2K4; CHUK; TSC2; TRAF2; TGFBR1; IRF3; TRAF6;STAMBP; BIRC7; PSMD10; CXCR4; NLK;STK4; EGFR; MALT1; STK3; PPP2CA; MAPK9; MAPK8; MKNK1; MAPK1; RIPK1; MAP2K7; MAP2K6; MAP4K4; SMAD1;MAP3K1; STAT1; STAT3; MAPK14; SOD1; NFKBIA; MAPK11; PINK1; RPS6KB1; BCL3; PKN1; TAB1; MYD88 |

| Protein amino acid phosphorylation | 6468 | 1.27 × 10–13 | 2.67 × 10–12 | 67 | 653 | GSK3B; CDKN1A;GSK3A; LRRK2; ILK; IGF1R; IKBKB; TBK1; TRIM28; CHEK1; AKT1; PRKACA; MAP3K7; MAP2K3; MAP2K4; PRKCI; CSNK2A1; CHUK; RIPK2; PDPK1; CSNK1E; TGFBR1; MAPKAPK3; LCK; BIRC7; SGK1; RAF1; MET; ROCK1; CTBP1; CXCR4; NLK; STK4; PRKCZ; EGFR; AURKB; STK3; AURKA; MAPK9; MAPK8; MKNK1; ERBB2; MAPK1; RIPK1; MAP2K7;PAK2; MAP2K6; MAP4K4; SMAD2; SMAD1; MAP3K1; STAT1; PLK1; EIF2AK2; MAPK14; PML; MTOR; SMAD7; SOD1; MAPK11; PINK1; CDK6; RPS6KB1;CDK4; CDK2; CDK1; PKN1 |

| Positive regulation of the I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB cascade | 43123 | 3.76 × 10–10 | 5.80 × 10–9 | 22 | 115 | RNF31; CHUK; RIPK2; CFLAR; PARK2; MALT1; RHOA; RELA; TNFRSF1A; PPP5C; PINK1; MAVS; TBK1; CASP8; TRAF6; UBE2N; RIPK1; TAB2; RBCK1; MAP3K7; MYD88; BIRC2; |

| Nuclear import | 51170 | 3.39 × 10–8 | 4.15 × 10–7 | 16 | 78 | JUN; ZFYVE9; RPL23; HTT; TSC2; CBLB; PML; NFKBIA; BCL3; CRY2; AKT1; MAPK1; HNRNPA1; RPL17; TP53; KPNB1 |

| Double-strand break repair | 6302 | 2.83 × 10–6 | 2.53 × 10–5 | 12 | 61 | RNF168; XRCC6; VCP; XRCC5; UIMC1; H2AFX; UBE2V2; UBE2N; BRCC3; BRCA1; TP53; SOD1 |

| Response to oxidative stress | 6979 | 8.59 × 10–5 | 5.52 × 10–4 | 19 | 184 | JUN; CHUK; DUSP1; STAT1; LRRK2; FOS; HIF1A; EGFR; PML; RELA; SOD1; FOSL1; PPP2CB; CASP6; PRDX1; CDK1; EP300; PRKACA; SNCA |

aTotal number of proteins found in the network that belong to a specific GO.

bTotal number of proteins belonging to a specific GO.

Fig. 5. Centrality analysis of proteins and ZnO interaction networks. Dashed lines represent the threshold value calculated for each centrality. Proteins and chemicals are represented by circular dots. Only proteins with a high bottleneck and node degree score are indicated.

4. Discussion

The results observed in this study indicate that ZnO NPs are genotoxic in the somatic cells of D. melanogaster, in flies with basal constitutive levels of cytochrome P-450 metabolizing enzymes. The sensitivity of D. melanogaster in nanotoxicology has been previously demonstrated.12,32,33 The genotoxicity of ZnO NPs has been widely demonstrated in vitro in different cell lines.5,34,35 Nevertheless, there is a lack of information regarding the genotoxicity of ZnO NPs in vivo. Reis et al.36 assessed the mutagenicity of two ZnO sources, amorphous crystals and nanoparticles, in the SMART. The authors demonstrated that amorphous ZnO and ZnO NPs were not mutagenic in the ST cross. Nevertheless, marker trans-heterozygous individuals from the HB cross treated with amorphous ZnO (6.25 mM) and ZnO NPs (12.50 mM) displayed a significantly high number of mutant spots, compared with the negative control. Our results demonstrated that ZnO NPs were genotoxic only in the ST cross. These controversial findings could be explained by the differences in the route of synthesis as well as in the structure and morphology of ZnO NPs. Thus, in our study ZnO NPs were synthesized using the sol–gel protein method and presented irregularly shaped particles with rounded-out edges and an average size of 86.73. On the other hand, in the study by Reis et al.,36 ZnO NPs were synthesized using a precipitation method and hexagonal-shaped particles were obtained, with some agglomerates and a mean size of 20 nm. The differences in the route of synthesis and shape of ZnO NPs could result in different genotoxic responses.

In this study, ZnO NPs were genotoxic to trans-heterozygous flies of the ST cross, but not to the HB cross. Differences in the results observed in the two crosses could be related to the high levels of cytochrome P-450 metabolizing enzymes in the HB cross, which could contribute to the detoxification of ZnO NPs before they can damage DNA of proliferative cells of D. melanogaster. The HB cross has a higher level of CYP6A2 than the ST cross.37 Since positive statistical diagnosis was observed in trans-heterozygous flies of the ST cross, the balancer heterozygous (mwh/TM3) flies were also scored, which afforded to quantify the contribution of mutagenic and recombinagenic events to the final genotoxicity observed.

Thus, we demonstrated that the genetic toxicity observed in this study was associated with a high frequency of homologous somatic recombination (HR) events, which means that HR is the basic cause of the mutant clone inductions observed in the SMART. HR is one of the main processes of genetic changes involved in the genesis and progression of cancer, occurring more frequently in proliferative cells.38

The induction of oxidative stress by the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been widely discussed in the specialized literature, and seems to be the main mechanism responsible for the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity associated with metallic-based nanomaterials.39 In fact, ZnO NPs increased intracellular ROS levels, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death.9,40 Sharma et al.6 demonstrated that oxidative stress could mediate genotoxicity in human epidermal cells after exposure to ZnO NPs. The production of ROS is directly correlated with the induction of DNA strand breaks,41 which could explain the high frequency of HR observed in this study.

The genotoxicity of ZnO NPs was recently revised by Scherzad et al.42 According to the authors there is still limited information regarding the genotoxic potential of ZnO NPs. In this context, the results obtained in our investigation contribute to the characterization of the genotoxic profile of ZnO NPs. To our knowledge this is the first study to quantify the contribution of HR and mutational events to the genotoxicity induced by ZnO NPs.

Additionally, we used a systems biology approach to shed more light on the mechanisms behind the genotoxicity of ZnO NPs. For this reason, a protein interaction network with ZnO was carried out.

As observed in our results, ZnO is related to the nuclear factor-kappa-beta (NFKB) protein family. NFKB is a transcription factor present in almost all cell types and tissues, and has been linked to many biological processes such as inflammation, immunity, differentiation, cell growth, tumorigenesis, and apoptosis (http://www.genecards.org). The NFKB family in mammals consists of the RELA, NFKB2, NFKB1, and REL subunits, which are proteins that contain a DNA-binding domain, a dimerization (or RHD) domain, and a nuclear localization signal domain.43 Commonly, in nonstimulated cells, NFKB is located in the cell cytosol bound to its inhibitory protein through its RHD domain, which blocks the nuclear location. In response to a remarkable diversity of external stimuli, including various physiological stress conditions, the signaling cascade is activated and its inhibitory protein is phosphorylated, leading to the nuclear translocation of NFKB and to the induction of transcription of target genes, such as its own inhibitory protein, NFKBIA.43,44

NFKBIA is a member of the NFKB inhibitor family, which interacts with REL dimers to inhibit NFKB/REL complexes (http://www.genecards.org). In accordance with the chemical–protein interaction database, ZnO increases phosphorylation, thus promoting the degradation of NFKBIA (; http://stitch.embl.de). According to our results, it is possible that NFKBIA phosphorylation promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of the NFKB inhibitor protein. Bioprocesses such as the ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, proteolysis involved in the cellular protein catabolic process, and protein amino acid phosphorylation were observed in our analysis of cluster 1, where NFKBIA appeared to be associated with these processes. Besides this, the major HBs in our network were involved in ubiquitination mechanisms. Phosphorylation often serves as a marker that triggers successive ubiquitination, mainly when ubiquitination leads to protein degradation.45 In the sense, Magnani46 affirms that, when there are external stimuli, the NFKB inhibitor (IκB) is phosphorylated and subsequently degraded. Phosphorylation targets IκB for ubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome, leading to NFKB transcription factor nuclear translocation. NFKBIA is an IκB, also called IκB-alpha (; http://www.genecards.org).

Response to oxidative stress was another bioprocess observed in gene ontology analysis. Also, it is possible that ZN NPs induce oxidative stress, increasing NFKBIA phosphorylation and promoting the nuclear translocation of NFKB dimers. Some studies have shown that ROS can both activate and inhibit NFκB signaling depending on the conditions.47 Song et al.48 showed that oxidative stress mediated NFκB activation to increase the phosphorylation of IκB-alpha after cerebral ischemia.

Another relevant bioprocess in cluster 1 was double-strand break (DSB) repair, where the NFKB protein family is present. There is a paucity of information about the contribution of NFKB to DNA repair. However, Volcic et al.49 observed that NFKB strongly stimulates the removal of DSBs by enhancement of HR in different cell lines. In addition, it has been consistently demonstrated that high concentrations of ROS are involved in the activation of the NFKB transcription factor. Interestingly, a higher frequency of HR was observed in the somatic cells of D. melanogaster exposed to ZnO NPs in our genotoxic analysis, possibly indicating excessive DSB repair. Thus, in silico and in vivo analyses were taken into consideration in the design of a molecular model of the ZnO effect and the increase in HR in D. melanogaster somatic cells (Fig. 6). In accordance with this model, ZnO exposure decreases NFKBI activity in cells, consequently increasing NFKB dimers levels in the nucleus and inducing DSB repair via HR. This HR excess can be observed in our results of SMART.

Fig. 6. A molecular model illustrating how ZnO could increase HR. ZnO exposure decreases NFKBI in the cell that consequently increases the nuclear translocation of NFKB dimers inducing DSB repair via HR.

Compared to materials at larger scales, nanomaterials may behave very differently.4 Due to their small size and large specific surface area, NPs exhibit unique physicochemical properties that may differ dramatically from their bulk counterparts.50,51 Altogether, the results of this study point to a genotoxic risk associated with the chronic in vivo exposure to ZnO NPs.

5. Conclusions

In this context, progress in understanding the genotoxicity of ZnO NPs could be achieved using the Drosophila melanogaster somatic mutation and recombination test (SMART) since this assay is able to detect mutational events like point and chromosomal mutations and HR in somatic cells. In proliferative cells, HR may result in loss of heterozygosity, revealing deleterious recessive mutations. In addition, the in silico approach contributed to clarify the ZnO mechanisms of action, revealing that NFKB could stimulate the removal of DSBs by enhancement of HR. Thus, considering the limited information regarding the genotoxic potential of ZnO NPs and the inconsistencies in the genotoxicological data available, this study contributed to the understanding of the genotoxic profile of ZnO NPs. The results of our study combined with the data from the scientific literature might contribute to assess the risk of ZnO NP application.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed in part by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. This work was supported by the Brazilian National Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq, grant number 457283/2014-9) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS).

References

- Dhawan A., Sharma V., Parmar D. Nanotoxicology. 2009;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Crane M., Handy D., Garrod J., Owen R. Ecotoxicology. 2008;17:421–437. doi: 10.1007/s10646-008-0215-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson K., Stone V., Tran C. L., Kreyling W., Borm P. J. A. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004;61:727–728. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.013243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H., Wang Y., Gua Y., Bowmanb L., Zhao J., Ding M. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017;38:3–24. doi: 10.1002/jat.3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman F., Baumgartner A., Cemeli E., Fletcher N., Anderson D. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:1193–1203. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Shukla K., Saxena N., Parmar D., Das M., Dhawan A. Toxicol. Lett. 2009;185:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Anderson D., Dhawan A. Apoptosis. 2012;17:852–870. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinlaan M., Ivask A., Blinova I., Dubourguier C., Kahru A. Chemosphere. 2008;71:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhang Y., Mao Z., Yu D., Gao C. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014;14:5688–5696. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.8876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf U., Wurgler F. E., Katz A. J., Frei H., Juon H., Hall C. B., Kale P. G. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1984;6:153–188. doi: 10.1002/em.2860060206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier E. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:9–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E., Turna F., Vales G., Kaya B., Creus A., Marcos R. Chemosphere. 2013;93:2304–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vales G., Demir E., Kaya B., Creus A., Marcos R. Nanotoxicology. 2013;7:462–468. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2012.689882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benford D. J., Hanley A. B., Bottrill K., Oehlschlager S., Balls M., Branca F., Castegnaro J. J., Descotes J., Hemminiki K., Lindsay D., Schilter B. ATLA, Altern. Lab. Anim. 2000;28:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses C. T., Flores W. H., Sasaki J. M. Chem. Mater. 2007;19:1024–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Mote V. D., Purushotham Y., Dole B. N. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2012;6:6. [Google Scholar]

- Frei H., Würgler F. E. Mutat. Res. 1995;334:247–258. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(95)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenbaum M. A., Bowman K. O. Mutat. Res. 1970;9:527–549. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(70)90038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade H. H. R., Reguly M. L. and Lehmann M., Wing Somatic Mutation and Recombination Test, in Drosophila Cytogenetics Protocols, ed. D. S. Henderson, Humana Press Inc., Totowa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D., Santos A., von Mering C., Jensen L. J., Bork P., Kuhn M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D380–D384. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D., Franceschini A., Wyder S., Forslund K., Heller D., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Roth A., Santos A., Tsafou K. P., Kuhn M., Bork P., Jensen L. J., von Mering C. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Deker T. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader G. D., Hogue C. W. BMC Bioinf. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S., Karel H., Martin K. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. Stat. Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Scardoni G., Petterlini M., Laudanna C. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2857–2859. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Kim P. M., Sprecher E., Trifonov V., Gerstein M. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi A. L., Oltvai Z. N. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomé S., Bizarro C. R., Lehmann M., De Abreu B. R., Andrade H. H. R., Cunha K. S., Dihl R. R. Mutat. Res. 2012;742:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dihl R. R., Bereta M. S., do Amaral V. S., Lehmann M., Reguly M. L., Andrade H. H. R. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:2344–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei H., Wurgler F. E. Mutat. Res. 1988;203:297–308. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(88)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepa Parvathi V., Rajagopal K. Int. J. NanoSci. Nanotechnol. 2014;5:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Demir E., Vales G., Kaya B., Creus A., Marcos R. Nanotoxicology. 2011;5:417–424. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.529176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E., Akça H., Kaya B., Burgucu D., Tokgün O., Turna F., Aksakal K., Vales G., Creus A., Marcos R. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014;264:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahab R., Kaushik N. K., Kaushik N., Choi E. H., Umar A., Dwivedi S., Musarrat J., Al-Khedhairy A. A. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013;9:1181–1189. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2013.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis E. M., Rezende A. A. A., Santos D. V., Oliveria P. F., Nicolella H. D., Tavares D. C., Silva A. C. A., Dantas N. O., Spanó M. A. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;84:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saner A., Weibel B., Würgler F. E., Sengstag C. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1996;27:46–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1996)27:1<46::AID-EM7>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop A. J., Schiestl R. H. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1471:109–121. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Liu C., Yang D., Zhang H., Xi Z. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009;29:69–78. doi: 10.1002/jat.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Zhang J., Guo J., Zhang J., Ding F., Li L., Sun Z. Toxicol. Lett. 2010;199:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kok T. M. C. M., Driece H. A. L., Hogervorst J. G. F., Briedé J. J. Mutat. Res. 2006;613:103–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzad A., Meyer T., Kleinsasser N., Hackenberg S. Materials. 2017;10:1427. doi: 10.3390/ma10121427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeckinghaus A., Ghosh S. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2009;1:a000034. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl H. L. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen P., Srihari S., Leong H. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14:S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S16-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani M., Crinelli R., Bianchi M., Antonelli A. Curr. Drug Targets. 2000;1:387–399. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. J., Liu Z. G. Cell Res. 2011;21:103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. S., Kim M. S., Kim H. A., Jung B. I., Yang J., Narasimhan P., Kim G. S., Jung J. E., Park E. H., Chan P. H. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1265–1274. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volcic M., Karl S., Baumann B., Salles D., Daniel P., Fulda S., Wiesmüller L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:181–195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala S. S. A., Aamanchi K. R. B., Phanindra K. A. V. and Amanchi A., Novel process of preparing nano metal and the products thereof, U.S. Patent 14/370974, 2015.

- Yin H., Casey P. S., McCall M. J., Fenech M. Langmuir. 2010;26:15399–15408. doi: 10.1021/la101033n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]