Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a chronic multisystemic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects young women of childbearing age group. There is a complex immunologic interplay during pregnancy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The pregnancy has direct impact on the disease where an increased rate of flares is noted, and lupus leads to increased risk of hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, preterm birth as well as miscarriages, particularly those with antiphospholipid antibodies. Neonates born to patients with lupus are at increased risk of neonatal lupus as well as heart block if born to patients with positive SSA/SSB. Despite the increased risk of morbidity, recent data suggest improved outcomes in pregnant patients with lupus. A multidisciplinary approach with careful monitoring of pregnancy and lupus could reduce adverse outcomes in these patients. This requires careful pregnancy planning, defining the clinical and serologic involvement of lupus, careful monitoring the patient for adverse pregnancy outcome as well as lupus flares and comprehensive understanding of the drugs that can be safely used in pregnancy. Fetuses should be carefully monitored for heart and neonates for neonatal lupus. Hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine and corticosteroids can be used during pregnancy and may reduce the risk of adverse outcomes. Similarly, appropriate therapy needs to be instituted for hypertensive diseases in pregnancy. Anticoagulant therapy may be necessary for patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Pregnancy, Antiphospholipid syndrome

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an multisystemic autoimmune disease which causes mucocutaneous manifestations, hematologic manifestations, renal and neurologic diseases aside from being associated with immunologic phenomena like a positive ANA, low complements, positive double stranded DNA, extractable nuclear antigen and antiphospholipid antibodies [1, 2]. These are the core components of Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria which are depicted in Table 1 [3]. A large case series of 1366 Indian lupus patients have demonstrated a high occurrence of renal and neurologic involvement. The prevalence of serologic abnormalities including prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies was similar to that reported by other countries but had low prevalence of clinical antiphospholipid syndrome [4].

Table 1.

Systemic lupus international collaborating clinics classification criteria

| Clinical criteria | Immunologic criteria |

|---|---|

| Acute cutaneous lupus | Antinuclear antibody |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | Anti-DNA antibody |

| Oral or nasal ulcers | Anti-Smith antibody |

| Non-scarring alopecia | Antiphospholipid antibody |

| Arthritis | Low complements (C3, C4 or CH50) |

| Serositis | Direct Coombs’ test in the absence of hemolytic anemia |

| Renal disease | |

| Neurologic disease | |

| Hemolytic anemia | |

| Leucopenia | |

| Thrombocytopenia |

Requirements: ≥ 4 criteria (at least 1 clinical and 1 laboratory criteria) or biopsy-proven lupus nephritis with positive ANA or anti-DNA

Epidemiologically, the prevalence of SLE in India is approximately 3.2 per 100,000 of the population [5]. The majority of lupus patients are females with men comprising only 4–18% of all patients. The mean age of disease onset in women is approximately 30, about 10 years earlier than that for men. It should be noted that lupus can affect prepubescent as well as postmenopausal women, latter often termed as “late onset lupus” [6, 7]. Given that the disease frequently affects women in reproductive age group, it is critical for both obstetricians and rheumatologists, to understand the interplay between the disease, the drugs used to treat the disease and the pregnancy state.

Most patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can have a successful pregnancy, but there is an increased maternal and fetal mortality and this high-risk situation imposes increased healthcare and economic burden [8, 9]. Hence, careful pregnancy planning, antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care along with careful monitoring of the newborn are needed to reduce this burden.

What Does Lupus do to the Pregnancy

There has been significant decline in the rates of pregnancy losses in patients with lupus. More than 80–90% of pregnancies result in live birth which has improved over time but continues to remain lower than the general population [8, 10, 11].

(1) Preterm birth The most common complication of lupus is preterm birth which can occur in approximately one-third of the patients [12, 13]. Risk factors for preterm delivery include increased disease activity (both clinical and serologic as reflected by increasing dsDNA titers and low complements), high prednisone use (which can cause premature rupture of membranes), hypertension and thyroid disease. A recent study by Clowse et al. [14] also noted elevated serum uric acid to be associated with preterm births. This in part may be reflective the hypertensive diseases in pregnancy, like preeclampsia and eclampsia, which are associated with elevated uric acid.

(2) Preeclampsia Patients with lupus have a high rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes including preeclampsia, pregnancy losses and intrauterine growth retardation as compared to general population. Preeclampsia has been noted to occur at about 2–3 times the rate in lupus patients as compared to those without lupus [15, 16]. Risk factors for preeclampsia include lupus and lupus nephritis-specific disease markers, presence of antiphosphoslipid antibodies, thrombocytopenia and reduced complement levels in addition to other predisposing factors like advanced maternal age, history of hypertensive disease in previous pregnancy, preexisting hypertension, diabetes and obesity [16, 17]. Preeclampsia poses a unique clinical challenge given the close resemblance between preeclampsia and lupus nephritis, both of which are characterized by deteriorating renal function, increasing proteinuria, hypertension and reduced platelet counts. Serum uric acid, which is elevated in preeclampsia, can help differentiate between the two. Kuc et al. [18] conducted a systematic review which evaluated 7 serum biomarkers (ADAM12, fβ-hCG, Inhibin A, Activin A, PP13, PIGF, PAPP-A) and Doppler ultrasound of the uterine vasculature in the first trimester to predict preeclampsia. However, delivery of the baby is sometimes the only definitive answer.

(3) Pregnancy loss and antiphospholipid antibodies Antiphospholipid antibodies occur in one-fourth to one-half patients with lupus; these rates are similar in Indian population as compared to the rest of the world [4, 5]. Notably, these antibodies can occur without coexistent lupus (primary antiphospholipid syndrome) and may still pose the same risk to the pregnancy. The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without antiphospholipid syndrome (APS; defined in Table 2) increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes like intrauterine growth retardation and preterm births [19]. Antiphospholipid syndrome itself is associated with pregnancy losses. The pathophysiology is thought to be related to thrombosis in uterine vasculature as well as binding of antibodies to trophoblasts, endothelial and neuronal cells [20]. Some authors have even associated these antibodies to movement disorders.

Table 2.

Definition of antiphospholipid syndrome

| A. Clinical criteria: 1. Vascular thrombosis: one or more arterial, venous or small vessel thrombosis 2. Pregnancy morbidity One or more fetal death at or beyond 10 weeks of gestation One or more premature births before 34th week of gestation because of eclampsia or placental insufficiency Three or more embryonic losses before 10 weeks of gestation |

| B. Laboratory criteria (titers should be positive on 2 occasions at least 12 weeks apart) 1. Lupus anticoagulant 2. Anticardiolipin antibody IgG or IgM at a medium or high titer (> 40) 3. B2 glycoprotein antibody IgG or IgM in medium or high titer (over 99th percentile) |

| Diagnosis requires at least one of the two clinical and one of the three laboratory criteria |

What Does Pregnancy do to Lupus

Most studies agree that there is an increased risk of flare of lupus associated with pregnancy. Most of the studies show the increased flare rates by 25–65% [15, 21]. A recent study completed by the investigators at Johns Hopkins University using Hopkins Lupus Cohort showed approximately 60% increased rate of flare in pregnant women as compared to non-pregnant patients; flares were defined as change in “Physician Global Assessment” of more than 1 from previous visit. The study also noted a significant effect modification with hydroxychloroquine, adjusted odds ratio for nonusers of hydroxychloroquine being 1.83 versus that of users being 1.26 [21].

It has been demonstrated that disease activity at the time of conception and the presence of lupus nephritis were significant predictors of flare during pregnancy [22–24]. Conversely, patients with 6 months of inactive disease at the time of conception and the absence of active renal disease significantly reduce the odds of flare during the pregnancy [25, 26]. It is also generally accepted that the flares of lupus during pregnancy are mild, generally involving the musculoskeletal, integumentary or hematologic systems [27]. Finally, flares of lupus may appear very similar to the pregnant state itself. For example, arthralgias, fatigue, lethargy and shortness of breath are common to both. Similarly, both are associated with cytopenias, mildly elevated inflammatory markers, etc.

Finally, it should be noted that de novo flares of lupus nephritis are rare during pregnancy, noted to be < 2% as compared to approximately 11% among those with history of renal disease (including those who were in remission). Buyon et al. [28] also noted the low C4 at baseline was also associated with high risk of de novo flares.

What Does Lupus do to the Newborn

Neonatal lupus Neonatal lupus is a temporary condition which lasts approximately 6 to 8 months after birth. Pathologically, it is due to passively acquire autoimmunity from maternal autoantibodies that cross the placenta and hence last until the maternal autoantibodies last in fetal circulation [29, 30]. It is usually characterized by a red-raised rash along with hematologic and hepatic abnormalities. It is seen in about 10% of patients who usually have positive SSA (anti-Ro) and SSB (anti-La) antibodies. In its most severe form, it can be associated with congenital heart block and hydrops fetalis but is also associated with cardiac conduction defects, structural abnormalities, cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure [31].

Complete Heart Block This is the most feared complication of neonatal lupus. It occurs in about 2% of newborns whose mothers have SSA or SSB antibodies. However, the recurrence rates are between 16 and 20% among those with a prior pregnancy resulting in a neonate with complete heart block. Complete heart block results in fetal mortality in 20% of the cases. Among the survivors, 70% require pacemaker insertion [32].

Conduction abnormalities can be detected as early as the second trimester of pregnancy starting at 16 weeks of gestation. However, there have reports of complete heart block even in the postpartum phase. Often lower degrees of conduction delays precede the development of complete heart block, although rapid development of complete heart block has been described [33].

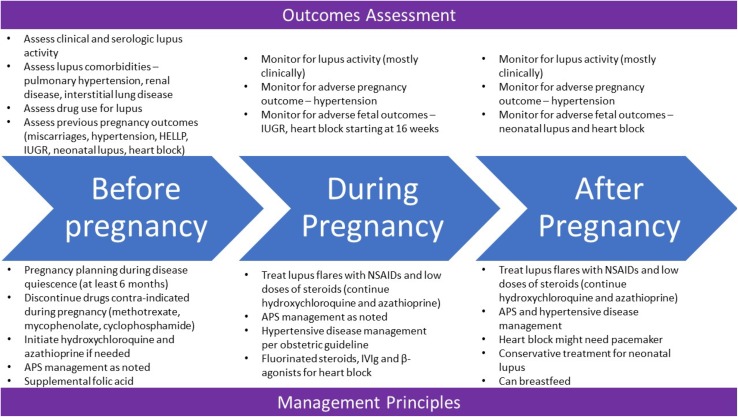

Treatment Considerations (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Summary of assessment and management of patients with lupus before, during and after pregnancy

Before pregnancy and pregnancy planning Women should discuss their desire to become pregnant with the caring medical team early and, ideally, should be planned. Women should be advised to avoid pregnancy if they have one of the high-risk comorbidities associated with lupus. This includes severe pulmonary hypertension, severe restrictive lung disease, advanced renal failure, advanced congestive heart failure, prior pregnancy with severe preeclampsia, eclampsia or HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) and recent stroke [34–37]. Women should plan pregnancy during a period of minimal disease activity or quiescence. As discussed previously, disease activity at the time of conception is the strongest predictor of adverse outcomes. Appropriate contraception should be used to ensure pregnancy planning. This would generally require extensive discussion with the caring gynecologist. While barrier contraceptives have a higher failure rates, hormonal preparations may be unsuitable for those with high risk of thrombosis.

In addition to routine investigations that are needed for pregnancy planning, additional laboratory investigation should be carried out to serologically define lupus. This should include evaluation of lupus serologies as well as urinalysis, complements, Sjogren’s antibodies and antiphospholipid antibodies. Nutritional supplementation with folic acid is recommended to reduce neural tube defects. Improved preconceptional cardiovascular health (total cholesterol, body mass index and blood pressure) has been associated with better pregnancy outcomes [38].

Hydroxychloroquine has been shown to reduce the rates of lupus flares in pregnant women. It is also associated with lower disease activity. Its role in reducing growth retardation has not been concretely established, but it may reduce occurrence of complete heart block in patients with SSA and SSB antibodies [39–42]. Azathiophine and steroids (at the lowest possible dose) can be continued during pregnancy. Drugs like methotrexate, mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide are teratogenic and need to be stopped prior to conception. There are very limited data about belimumab and rituximab use during pregnancy

During pregnancy It is important to recognize features of lupus flare or active lupus versus features of complications of pregnancy, especially because the two may overlap. If the patient is on hydroxychloroquine or antimalarials, these should be continued. Flares of lupus, particularly arthritis, can be treated with nonsteroidal analgesics. Beyond 32 weeks of gestation, NSAIDs are associated with premature closure of ductus arteriosus and should be stopped. If needed, short course with the lowest possible dose of steroids can be used for flare of lupus; fluorinated steroids like betamethasone or dexamethasone should be used no more than once [43]. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with high disease activity and worse pregnancy outcomes. Hence, calcium and vitamin D supplementation should be considered

Antiphospholipid antibodies: Management of patients with antiphospholipid antibodies requires risk stratification and use of antiplatelet agents/heparin. Patients are stratified into one of the three categories [15]

Asymptomatic carriers (positive antibodies without previous obstetric complications or thrombosis) usually do not require any therapy; however, the use of aspirin is common

Obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome (positive antibodies with previous obstetric complications but without thrombosis): These patients should be treated with a combination of aspirin along with prophylactic doses of heparin

Patients with established antiphospholipid syndrome with prior thrombosis require therapeutic doses of heparin throughout the pregnancy until approximately 6 weeks postpartum

* Low molecular weight heparin (like enoxaparin) can be used in place of unfractionated heparin. Coumadin is contraindicated in pregnancy

Patients with positive Sjogren’s serologies are at increased risk of heart block. Neonatal lupus is usually self-resolving [43]. Monitoring for this complication should start as early as 16 weeks of gestation and should be done weekly until 26 weeks and every 2 weeks thereafter. Fetal echocardiography is at the core of such evaluations. Even milder conduction delays like PR prolongations should prompt discussion. Fluorinated steroids and β-agonists can be tried to improve fetal survival. IVIg has also been tried in such situation, but the merit is often debated.

Hypertensive disease in pregnancy is more common in lupus patients than those without. The treatment of this disease should follow routine obstetric guidelines

After the pregnancy Breastfeeding is considered safe in lupus patients. As such, medications like hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, methotrexate and prednisone have very limited transfer into breast milk and can be continued while breastfeeding [44]. Neonatal lupus is self-resolving and does not need any therapy.

Conclusion

Pregnancy outcomes in patients with lupus have improved considerably over time. Yet, lupus continues to present increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes and pregnancy increases the risk of lupus flares. A thorough understanding of the pathophysiologic processes involved and a multidisciplinary team are needed from careful planning of pregnancy to delivery of the fetus.

Deepan S. Dalal

is a consultant rheumatologist at Brown Medicine and is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Brown University Warren Alpert School of Medicine. He is a graduate of TN Medical College, Mumbai, and has completed his residency in Internal Medicine and Rheumatology at Cleveland Clinic Foundation and Boston University. He has also completed his Masters in Public Health from the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Deepan S. Dalal is a MD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Medicine at Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Brown University Warren Alpert Medical School, 375 Wampanoag Trail, #302C, E. Providence, RI 02915, USA. Dr. Khyati A. Patel is a currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at Brown University. She is a graduate of TN Medical College after which she completed dual residencies - one in Obstetrics and Gynecology at Lokmanya Tilak Memorial Hospital and Family Medicine at Case Western Reserve University. In her busy clinical practice, she focuses on women’s health related issues in addition to general medical care of patients. She is actively engaged in education of medical students at Brown University. Dr. Madhuri A. Patel is an Honorary Clinical Associate in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Nawrosjee Wadia Maternity Hospital in Mumbai. She completed her medical school and residency in Obstetrics and Gynecology at Grant Medical College and Cama & Albless Hospital affiliated with Grant Medical College in Mumbai. She has previous served in various academic and administrative positions at Grant Medical College and Police Hospital, Mumbai. She is currently Deputy Secretary General in FOGSI and Joint Associate Editor of JOGI and has delivered several national and international talks on various issues related to Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stojan G, Petri M. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):144–150. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu C, Gershwin ME, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2014;48–49:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2677–2686. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malaviya AN, Chandrasekaran AN, Kumar A, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in India. Lupus. 1997;6(9):690–700. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malaviya AN, Singh RR, Singh YN, et al. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in India. Lupus. 1993;2(2):115–118. doi: 10.1177/096120339300200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim SS, Drenkard C. Epidemiology of lupus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27(5):427–432. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace DJ, Hahn BH. Dubois’ lupus erythematosus and related syndromes. 8. Amsterdam: Saunders Elsevier; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark CA, Spitzer KA, Laskin CA. Decrease in pregnancy loss rates in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 40-year period. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(9):1709–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petri M, Daly RP, Pushparajah DS. Healthcare costs of pregnancy in systemic lupus erythematosus: retrospective observational analysis from a US health claims database. J Med Econ. 2015;18(11):967–973. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2015.1066796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakravarty EF, Nelson L, Krishnan E. Obstetric hospitalizations in the United States for women with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):899–907. doi: 10.1002/art.21663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clowse ME, Jamison M, Myers E, et al. A national study of the complications of lupus in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(2):127.e1–127.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Yuen S, Krizova A, Ouimet JM, et al. Pregnancy outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is improving: results from a case control study and literature review. Open Rheumatol J. 2008;2:89–98. doi: 10.2174/1874312900802010089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark CA, Spitzer KA, Nadler JN, et al. Preterm deliveries in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(10):2127–2132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clowse ME, Wallace DJ, Weisman M, et al. Predictors of preterm birth in patients with mild systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(9):1536–1539. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lateef A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus and pregnancy. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2017;43(2):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(4):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakravarty EF, Colon I, Langen ES, et al. Factors that predict prematurity and preeclampsia in pregnancies that are complicated by systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(6):1897–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuc S, Wortelboer EJ, van Rijn BB, et al. Evaluation of 7 serum biomarkers and uterine artery Doppler ultrasound for first-trimester prediction of preeclampsia: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66(4):225–239. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3182227027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Puerta JA, Cervera R. Diagnosis and classification of the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2014;48–49:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy RA, Dos Santos FC, de Jesus GR, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and antiphospholipid syndrome during pregnancy: diagnostic concepts. Front Immunol. 2015;7(6):205. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eudy AM, Siega-Riz AM, Engel SM, et al. Effect of pregnancy on disease flares in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):855–860. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyth A, Oliveira GH, Lahr BD, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(11):2060–2068. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00240110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imbasciati E, Tincani A, Gregorini G, et al. Pregnancy in women with pre-existing lupus nephritis: predictors of fetal and maternal outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(2):519–525. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gladman DD, Tandon A, Ibanez D, et al. The effect of lupus nephritis on pregnancy outcome and fetal and maternal complications. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(4):754–758. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petri M, Howard D, Repke J. Frequency of lupus flare in pregnancy. The Hopkins Lupus Pregnancy Center experience. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(12):1538–1545. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner SJ, Craici I, Reed D, et al. Maternal and foetal outcomes in pregnant patients with active lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2009;18(4):342–347. doi: 10.1177/0961203308097575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petri M. The Hopkins Lupus Pregnancy Center: ten key issues in management. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33(2):227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, et al. Kidney outcomes and risk factors for nephritis (flare/de novo) in a multiethnic cohort of pregnant patients with lupus. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(6):940–946. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11431116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanoni F, Lava SAG, Fossali EF, et al. Neonatal systemic lupus erythematosus syndrome: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53(3):469–476. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein-Gitelman MS. Neonatal lupus: what we have learned and current approaches to care. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(9):60-016-0610-z. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0610-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brito-Zeron P, Izmirly PM, Ramos-Casals M, et al. The clinical spectrum of autoimmune congenital heart block. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(5):301–312. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brito-Zeron P, Izmirly PM, Ramos-Casals M, et al. Autoimmune congenital heart block: complex and unusual situations. Lupus. 2016;25(2):116–128. doi: 10.1177/0961203315624024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonesson SE. Diagnosing foetal atrioventricular heart blocks. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72(3):205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pieper PG, Hoendermis ES. Pregnancy in women with pulmonary hypertension. Neth Heart J. 2011;19(12):504–508. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hladunewich M, Hercz AE, Keunen J, et al. Pregnancy in end stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2011;24(6):634–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grewal J, Silversides CK, Colman JM. Pregnancy in women with heart disease: risk assessment and management of heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10(1):117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aydin S, Ersan F, Ark C, et al. Partial HELLP syndrome: maternal, perinatal, subsequent pregnancy and long-term maternal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(4):932–940. doi: 10.1111/jog.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eudy AM, Siega-Riz AM, Engel SM, et al. Preconceptional cardiovascular health and pregnancy outcomes in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2018;46:70. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.171066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillotin V, Bouhet A, Barnetche T, et al. Hydroxychloroquine for the prevention of fetal growth restriction and prematurity in lupus pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85:663. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izmirly PM, Kim MY, Llanos C, et al. Evaluation of the risk of anti-SSA/Ro-SSB/La antibody-associated cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus in fetuses of mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus exposed to hydroxychloroquine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1827–1830. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izmirly PM, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Pisoni CN, et al. Maternal use of hydroxychloroquine is associated with a reduced risk of recurrent anti-SSA/Ro-antibody-associated cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus. Circulation. 2012;126(1):76–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy RA, Vilela VS, Cataldo MJ, et al. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in lupus pregnancy: double-blind and placebo-controlled study. Lupus. 2001;10(6):401–404. doi: 10.1191/096120301678646137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxena A, Izmirly PM, Mendez B, et al. Prevention and treatment in utero of autoimmune-associated congenital heart block. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22(6):263–267. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noviani M, Wasserman S, Clowse ME. Breastfeeding in mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2016;25(9):973–979. doi: 10.1177/0961203316629555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]