Abstract

The effect of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on plant cells, since their phytotoxicity potential is not yet fully understood. In this context, the aim of the present study was to elucidate the effects of AgNPs in the in vitro culture of Physalis peruviana. For this purpose, P. peruviana seeds were grown in MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of AgNPs. Growth and development of seedlings were evaluated through germination, seedling size and biomass and biochemical and anatomical analyses. At the end of 60 days of cultivation, it was observed that the in vitro germination of this species is not affected by the presence of AgNPs and that at low concentrations (0.385 mg L−1) it can promote an increase in seedlings biomass. However, higher concentration (15.4 mg L−1) leads to a reduction in seedling size and root system, but no changes were observed in the seedlings antioxidant metabolism and anatomy. These results demonstrate that the phytotoxicity of AgNPs in P. peruviana is related to the concentration of nanoparticles to which the specie is exposed.

Keywords: AgNPs, Nanotechnology, Phytotoxicity, Tissue culture, Solanaceae

Introduction

Based on the increasing development of nanotechnology, the application of nanomaterials in various fields has expanded significantly. Nanomaterials have one or more dimensions in the range from 1 to 100 nm (Amenta et al. 2015), implying in new properties, different from those of the isolated atom and its size in macrometric scale (Albrecht et al. 2006).

Due to these unique properties, a variety of materials at the nanoscale are being developed, including carbon nanotubes, nanoparticles of iron, aluminum, copper, gold, silver, silica, zinc, zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, and others.

Among the nanomaterials, silver nanoparticles are widely used due to their antimicrobial properties, being reported the presence of AgNPs in more than 400 commercialized products (Vance et al. 2015). It has been used in the treatment of water (Loo et al. 2015), food packaging (Moura et al. 2012), medicine (Zhang et al. 2016), agriculture (Prasad et al. 2017), among others.

It has been shown that AgNPs can improve the growth and development of potato cultured in vitro (Bagherzadeh Homaee and Ehsanpour 2015), stimulate the growth of brown mustard (Pandey et al. 2014), stimulate increased biomass in Arabidopsis (Kaveh et al. 2013) and increase the life span and multiply the shoots of rugtrora explants cultured in vitro (Sarmast et al. 2015).

However, it has also been reported that AgNPs can significantly reduce the growth of cucumber (Tripathi et al. 2017a) and giant duckweed by affecting photosynthetic performance and increasing oxidative stress (Jiang et al. 2017), reducing growth and nutrient content in radish (Zuverza-mena et al. 2016), inhibit root elongation and leaf expansion of Arabidopsis, thus decreasing the photosynthetic efficiency, besides promoting an accumulation of Ag+ ions in the plant tissues (Sosan et al. 2016). AgNPs also inhibit the growth, pigments and photosynthesis of pea (Tripathi et al. 2017b) and induced various chromosomal abnormalities in the mitotic and meiotic cells of onion (Saha and Dutta Gupta 2017).

It is evident that there are still gaps regarding of AgNPs effects on plant cells, whose results are contradictory, with positive and negative effects according to the plant species, the concentration used and the nanoparticle size (Cox et al. 2017). Thus, researches are being conducted to evaluate the toxicity of AgNPs in living organisms (Jung et al. 2018) especially in plant species such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Li et al. 2018).

In this context, it was aimed to analyze the effect of AgNPs on the in vitro development of Physalis peruviana L., a species with great potential for phytotoxicity studies, since it shows physicochemical properties already elucidated in the literature and belongs to the Solanaceae family, covering relevant species such as potato, tomato and tobacco.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized according to the methodology described by (Turkevich et al. 1951) with adaptations. A solution was prepared with silver nitrate (0.18 g L−1) and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (0.6 g L−1), remaining under constant heating and stirring. At 95 °C, an aqueous solution of 1% sodium citrate was added thereto.

The concentration of the AgNPs solution was quantified by UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy (UV-1800 model, Shimadzu). Silver nanoparticle solution has a characteristic peak at 390–420 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The intensity of the peak is proportional to the AgNPs concentration of the measured solution. Thus, the absorbance of the silver nanoparticle solution at the peak of 420 nm was compared with a calibration curve obtained from solutions of silver nanoparticles of known concentration.

Characterization of silver nanoparticles

Stock solution of silver nanoparticle was characterized through dynamic light scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential. Morphological analysis of AgNPs was obtained by transmission electronic microscopy (TEM).

DLS and Zeta Potential were analyzed using a Malvern 3000 Zetasizer equipment during 2 months of storage to verify the stability and size of the AgNPs throughout the storage time. For analysis of the solution, 0.5 mL sample suspension was added in 100 mL deionized water, sonicated in an ultrasonic tip (Brason) for 1 min at a power of 450 W.

Morphology of AgNPs was analyzed after 15 days of synthesis, in transmission electronic microscope (Magellan 400 L). The samples were diluted using the same procedure for DLS and Zeta Potential analysis. The suspensions were stored in a 400 mesh copper grid.

In vitro culture

Seeds of physalis were manually extracted from purchased mature fruits and the mucilage was removed in running tap water, then the seeds were dried for 24 h at room temperature and stored at 4 °C until use.

In laminar flow, the seeds were disinfested first at 70° GL alcohol for 30 s and immersed in 1% (v/v) commercial sodium hypochlorite solution and two drops of tween 20 for 10 min. After passing through three rinses in autoclaved deionized water, seeds were inoculated in MS culture medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962), (30 g L−1 sucrose) supplemental with different concentrations of AgNPs (0.0, 0.385, 0.77, 1.54 and 15.4 mg L−1), and solidified by 7 g L−1 agar. The pH of the culture medium was adjusted to 5.7 ± 0.1 and autoclaved at 121 °C and 1 atm pressure for 20 min.

After inoculation, the material was transferred to the growth room where it remained for 60 days at a temperature of 25 °C, in 16 h photoperiod (fluorescent lamps of 36 µmol m−2 s−1) for germination and development of seedlings until later evaluation.

Growth analysis

After 45 days of cultivation, seed germination rate, number of normal plants, fresh and dry mass of seedlings, size of shoot and main root, and chlorophyll content of the obtained seedlings were analyzed. Seedlings were considered as normal when they showed fully expanded leaves and formed roots.

The fresh mass (mg) was obtained immediately after the removal of seedlings from the test tubes and the dry mass (mg) after 24 h dehydration of plants in oven (100 °C). The size of shoot and main root was obtained in an automated way by the GroundEye® equipment. The chlorophyll content was measured by an atLEAF portable chlorophyll meter.

Light microscopy

For the anatomical studies, samples of leaves, stem and root with 60 days of culture were collected and stored in 70% (v/v) alcohol until anatomical sections were taken. For the preparation of permanent slides, samples of leaves, stems and roots were sectioned in about 0.5 cm2, dehydrated in increasing ethylic series and included in methacrylate (Historesin, Leica Instruments, Heidelberg, Germany).

The cross sections of leaves, stem and roots were performed in a 8 µm thick microtome, stained with toluidine blue (O’Brien et al. 1964) and the sealed slides using colorless stained glass (Acrilex).

The prepared slides were observed and photographed under a Zeiss Scope AX10® microscope coupled to the digital camera and photomicrographed in Axio Vision R.L. 4.8® software. The presence or absence of cell damage was analyzed.

Biochemical analysis of antioxidant metabolism and lipid peroxidation

At 60 days, samples for biochemical analysis were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in a freezer at − 80 °C. The enzymatic extract for biochemical analysis was obtained by the maceration in liquid nitrogen of 200 mg fresh material of shoot from the seedlings germinated in vitro, to which was added 1.5 mL extraction buffer, composed of potassium phosphate buffer (400 mM) at pH 7.8; 15 µL EDTA (10 mM); 75 µL ascorbic acid (200 mM) and 1035 µL water (Biemelt et al. 1998). The extract was centrifuged at 13,000g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected for the analysis of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) using the methodology described by Nakano and Asada (1981), catalase (CAT) Havir and McHale (1987) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), evaluated according to Giannopolitis and Ries (1977).

Lipid peroxidation was determined according to the Buege and Aust (1978), where the fresh material of shoot (200 mg) from the seedlings was macerated in liquid nitrogen, added with PVPP (Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone) and homogenized in 0.1% (m/v) 1.5 mL trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Lipid peroxidation was expressed in nanomol of MDA mg−1 FM.

Statistical design

The experiment was performed in a completely randomized design, with 30 replicates per treatment, being considered one plant per replicate. The data were submitted to analysis of variance using the statistical software SISVAR (Ferreira 2014) and the means were analyzed by the Scott-Knott test at 5% probability.

Results

Characterization of silver nanoparticles

The characterization and stability analysis of AgNPs are important to evaluate their mode of action in plant species, since the effect of nanoparticles on plant tissues may vary according to size, concentration and stability.

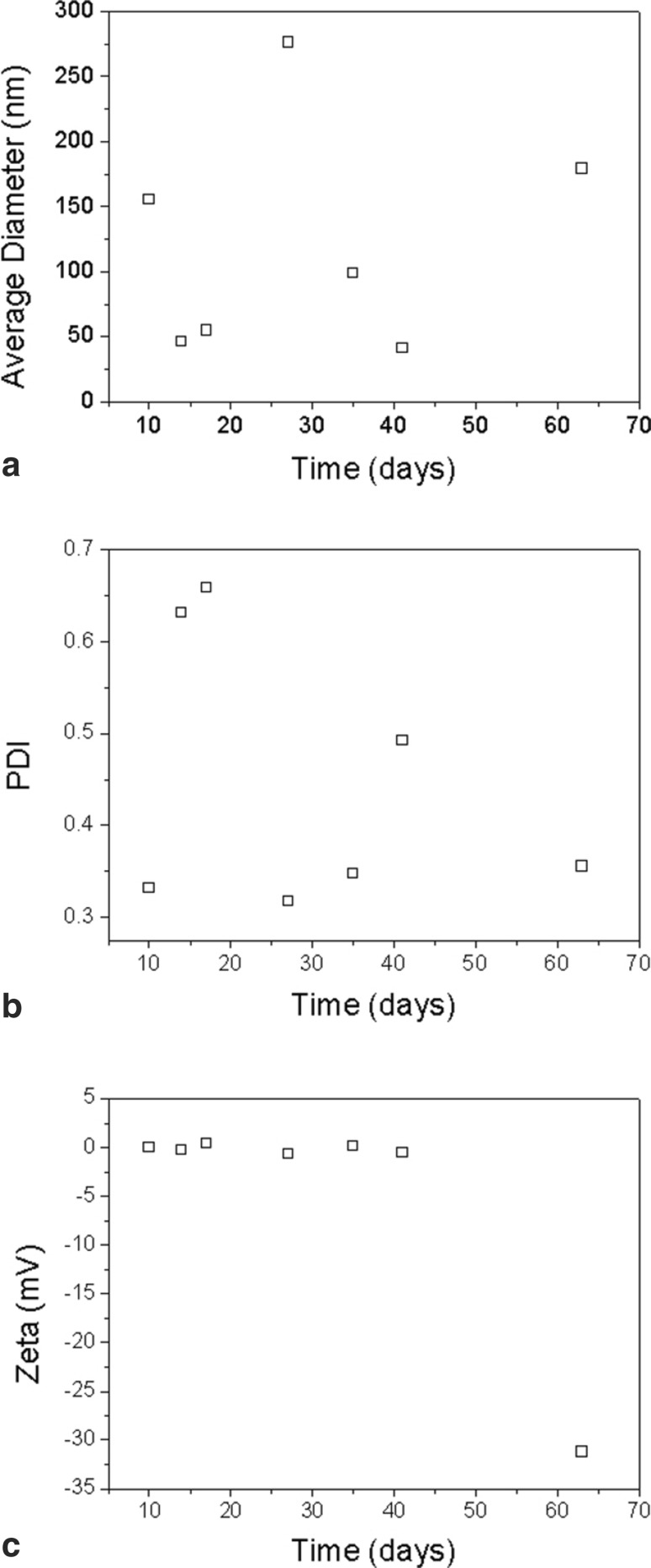

AgNP size distribution varied over the storage period of the synthesized solution, shown average size of 121.6 nm (Fig. 1a). The Polydispersity Index also shows a variation in the polydispersity of nanoparticles with average of 0.45 (Fig. 1b). The Zeta Potential near zero indicates a solution that remains unstable during the storage period (Fig. 1c). These characteristics indicate that the synthesized silver nanoparticles tend to aggregate, which leads to an increase in size.

Fig. 1.

a Distribution of silver nanoparticle sizes (AgNPs), b Polydispersity Index (PDI) and c Zeta Potential after storage periods of the synthesized solution of AgNPs

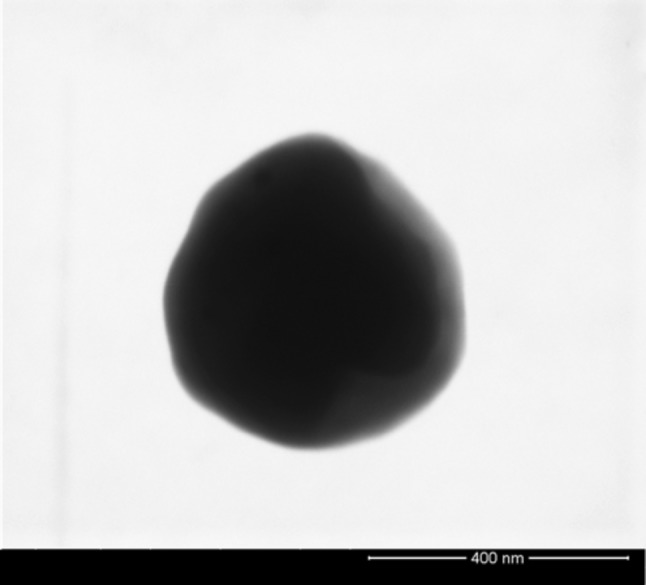

Transmission electron microscopy, performed after 15 days storage of the stock solution, showed that the AgNPs formed by chemical synthesis had a spherical morphology (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Morphology of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), 15 days after stock solution synthesis

Growth analysis

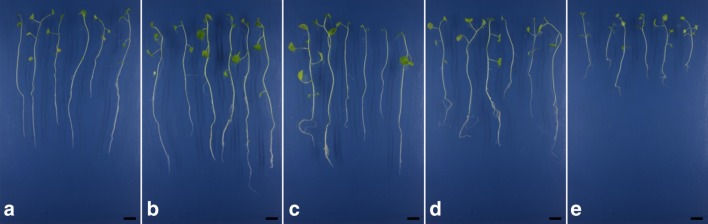

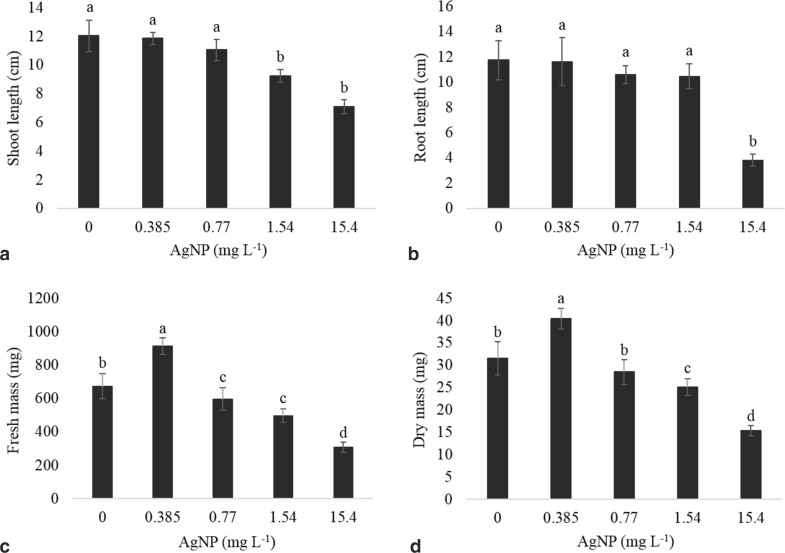

The presence of AgNPs in the culture medium did not affect the in vitro germination of physalis seeds, since 100% germination and 100% normal plants were observed in all treatments (Fig. 3). However, continuous exposure to nanoparticles affected shoot length of obtained seedlings at highest concentrations (Figs. 3, 4a). A reduction of 67% in the root length was observed at the concentration of 15.4 mg L−1 when compared to plants cultured in the absence of AgNPs (Figs. 3, 4b).

Fig. 3.

Physalis peruviana seedlings at 45 days of culture subjected to different concentrations of AgNPs: a 0.0; b 0.385; c 0.77; d 1.54 and e 15.4 mg L−1 silver nanoparticles. Bar: 2 cm

Fig. 4.

Shoot length (a) and root length (b), fresh mass (c) and dry mass (d) of Physalis peruviana seedlings cultured in vitro at different concentrations of silver nanoparticles. Averages followed by the same letter do not differ statistically among themselves by Scott-Knott test at 5% probability level

In contrast, seedlings exposed to the treatment with 0.385 mg L−1 AgNPs showed an increase of about 36% and 28% in their fresh and dry mass, respectively, when compared to plants cultured in the absence of AgNPs (Fig. 4c, d). Correspondingly, the fresh and dry mass of seedlings subjected to 15.4 mg L−1 AgNPs was also reduced by almost 50% when compared to the treatment with absence of nanoparticles (Fig. 4c, d).

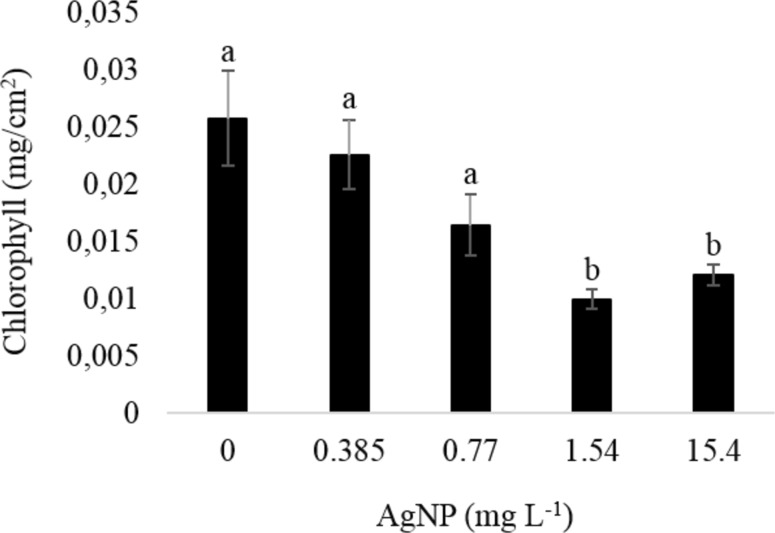

A significant reduction in the chlorophyll content was observed in the higher concentration (1.54 and 15.4 mg L−1) of silver nanoparticles used (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Chlorophyll content of Physalis peruviana leaves cultured in vitro in the presence of silver nanoparticles. Averages followed by the same letter do not differ statistically among themselves by Scott-Knott test at 5% probability level

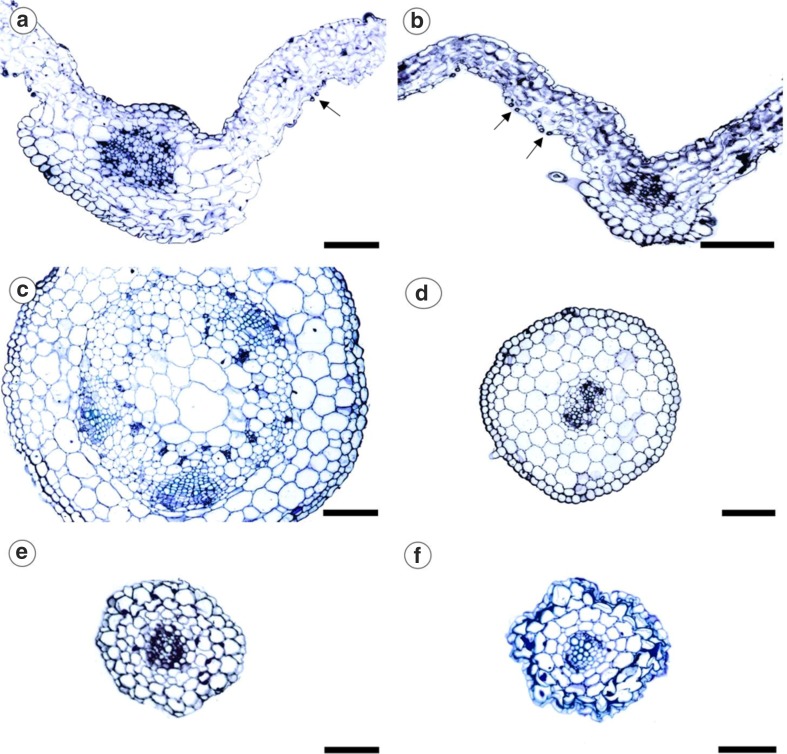

Light microscopy

It is observed that physalis leaves cultured in vitro in the presence or absence of AgNPs showed stomata on the adaxial and abaxial surfaces, being classified as amphistomatic leaves, with stomata occurring in higher quantity in the abaxial face. The parenchyma showed cells of irregular shape, with large intercellular spaces, being difficult the classification between palisade and spongy parenchyma due to the in vitro culture environment (Fig. 6a, d).

Fig. 6.

Cross sections of leaf (a), stem (c) and root (e) of Physalis peruviana seedlings cultured in vitro in the abscence of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). Cuttings of leaf (b), stem (d) and root (f) of seedlings cultured in the presence of 15.4 mg L−1 AgNPs. Arrows indicate the stomata. Bar: 10 µM

The stems and roots showed the beginning of the primary growth and the presence of stomata in the stems was observed in the treatments with AgNPs. In the absence of AgNPs, a better development of vascular bundles in stems is observed, with clear formation of bundles around the pith (Fig. 6b, e). Moreover, no cell damage was observed in the leaf, stem and root sections of plants cultured in the presence of AgNPs, regardless of the used concentration in relation to seedling from the control treatment (Fig. 6).

Biochemical analysis of antioxidant metabolism and lipid peroxidation

Exposure of plants to AgNPs may lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species. Thus, the analysis of antioxidant metabolism is an important tool to determine the effects of nanoparticles in plant tissues.

Regarding the response of antioxidant enzymes, the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) did not differ significantly among treatments. However, catalase (CAT) activity was lower in the treatments with 0.385 and 15.4 mg L−1 AgNPs (Table 1). Measurements of lipid peroxidation showed no significant changes in MDA levels in the shoot (Table 1).

Table 1.

Activity of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX) and lipid peroxidation (MDA)

| Concentration of AgNP (mg L− 1) | SOD (U mg− 1 fresh mass)* | CAT (µmol H2O2 min− 1 mg− 1 fresh mass)* | APX (µmol AsA min− 1 mg− 1 fresh mass)* | MDA (ηmol mg− 1 fresh mass)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.88a | 1.91a | 10.68a | 248.08a |

| 0.385 | 0.82a | 1.25b | 9.54a | 221.15a |

| 0.77 | 0.84a | 2.26a | 12.15a | 224.61a |

| 1.54 | 0.86a | 2.01a | 8.38a | 239.42a |

| 15.4 | 0.80a | 0.83b | 10.51a | 213.14a |

*Averages followed by the same letter do not differ statistically among themselves by Scott-Knott test at 5% probability level

Discussion

It was observed that the exposure to AgNPs does not affect the in vitro germination of physalis, and can improve the development of in vitro seedlings at low concentrations, since the concentration of 0.385 mg L−1 increased the biomass of the obtained seedlings. This dose-dependent effect was also observed in arabidopsis in which exposure to AgNPs significantly increased biomass at concentrations of 1.0 and 2.5 mg L−1, and reduced exposures from 5.0 to 20 mg L−1 (Kaveh et al. 2013). Similar results were observed in the dragon fruit, whose seed exposure to AgNPs did not affect in vitro germination and provided an increase of the root system (Timoteo et al. 2018).

In a study performed by Syu et al. (2014) with arabidopsis it was observed that AgNPs can act as plant growth stimulators by increasing accumulation of cell cycle-related proteins, chloroplast biogenesis and carbohydrate metabolism. It can positively affect different cellular pathways of important processes in plant cells, thus promoting a better plant development at low concentrations.

However, at the concentration of 15.4 mg L−1, AgNPs were detrimental to the in vitro development of roots in physalis seedlings, since root size was reduced by 67% in plants exposed to this concentration. Reductions in the root system were also observed in maize where roots exposed to AgNPs showed damages in their development (Pokhrel and Dubey 2013).

Roots are the primary tissues through which AgNPs enter in plants, making them the most responsive organ to their effects. In arabidopsis, it was reported that the AgNPs are accumulated in the initial cells of the root columella, preventing the cell division and hence the growth of roots (Geisler-Lee et al. 2012). In relation to the transport of AgNPs by roots, their presence was reported in plasmodesmata and the cell wall, which would result in a physical block in the symplastic transport and interruption of the intercellular communication and the transport of nutrients (Geisler-Lee et al. 2014).

Thus, the reduction in root length observed in physalis when exposed to 15.4 mg L−1 AgNPs may be related to this accumulation of AgNPs in the columella, which would potentially hinder root growth and/or the presence of AgNPs in the plasmodesmata, precluding the transport of nutrients in these places, since a reduction of approximately 50% fresh mass in plants exposed to this same concentration was also observed.

It has been observed that AgNPs altered the absorption of metal ions important for the plant development. In radish, a reduction in Ca, Mg, B, Cu, Mn and Zn absorption was observed by Zuverza-mena et al. (2016). This would also lead to a reduction in plant development, as observed in physalis, in which the shoot was reduced when exposed to 1.54 and 15.4 mg L−1 AgNPs.

The content of photosynthetic pigments can also be affected by AgNPs, as observed in physalis, where the chlorophyll content was reduced in treatments with 1.54 and 15.4 mg L−1 AgNPs. Similar results were verified in arabidopsis seedlings whose chlorophyll content was also reduced when subjected to AgNPs, besides causing structural alterations in the chloroplasts, which could lead to changes in the photosynthetic metabolism and hence affect the development of seedlings (Nair and Chung 2014).

In some cases, the phytotoxicity of AgNPs may be associated with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (Jiang et al. 2017). Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) are enzymatic antioxidants that catalyze the decomposition of ROS (Homaee and Ehsanpour 2016).

In potato belonging to Solanaceae family was related a significant increase in the activities of SOD, CAT, APX and glutathione reductase (GR) was reported due to the increase of oxidative stress caused by the increase of ROS in plants cultured in vitro in the presence of AgNPs (Homaee and Ehsanpour 2016). In the in vitro multiplication of gabiroba, the presence of AgNPs in the culture medium caused no changes in the content of the SOD enzyme (Timoteo et al. 2019).

However, no significant differences were observed between the control and the other AgNPs concentrations in relation to the SOD and APX enzymes in the in vitro culture of physalis. In the present study, the long period (60 days) in which the plants were grown in a growth room where the AgNPs supplemented culture medium remained exposed to light irradiation may have caused changes in AgNPs size and, consequently, decreased their toxicity. It has been reported in Tetrahymena pyriformis that light can influence the toxicity of AgNPs, whose results demonstrated that light irradiation induced AgNPs growth and caused mass agglomeration, thereby decreasing the surface area and the number of Ag+ ions released from AgNPs, which led to lower toxicity (Shi et al. 2012).

Consequently, with a lower toxicity rate, the oxidative stress would not be observed at 60 days of culture in physalis, which could explain the similar activity of antioxidant metabolism enzymes (SOD, CAT and APX) between plants cultured in the absence and presence of AgNPs. As already demonstrated, the toxicity of AgNPs is closely related to the size and concentration of the nanomaterial in the culture medium (Wang et al. 2013).

The anatomical results demonstrated that AgNPs did not cause cell damage in leaves, stems and roots of physalis seedlings. These results corroborate the lipid peroxidation analyses, in which no significant differences were observed between seedlings cultured in the presence and absence of AgNPs.

Based on the obtained results, AgNPs were not shown as potentially toxic to physalis at low concentrations, which may be related to the agglomeration of silver nanoparticles caused by the exposure of cultures to light radiation, to the size of nanoparticles obtained by the used chemical synthesis, to surface coating of AgNPs used in the present study (sodium citrate) and to the surface charge of nanoparticles obtained by the Zeta Potential. The average Zeta Potential of − 4.58 mV indicates an unstable solution, as a result of the increased aggregation of nanoparticles, increasing its size and decreasing the toxicity of AgNPs.

Sodium citrate coated nanoparticles were shown as less toxic than cetrimonium bromide (CTAB) or polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) coated AgNPs in onion by promoting formation of larger silver nanoparticles during synthesis (Cvjetko et al. 2017). As has already verified, smaller AgNPs are more toxic than larger AgNPs (Wang et al. 2013). In the present study, the AgNPs predominantly showed average size of 121.6 nm.

Therefore, due to its larger size and high aggregation potential which was increased by light exposure, the AgNPs synthesized in the present study did not showed no toxicity to physalis seedlings except at high concentrations.

Conclusions

Low concentrations of AgNPs do not affect the in vitro germination of physalis and may promote an increase in seedling biomass. However, higher concentrations affect its in vitro growth and development.

This study demonstrates that the phytotoxicity of AgNPs is related to the concentration of the nanoparticles to which the plant species is exposed.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. Sincere thanks to the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), for financial support. We are also grateful to the National Laboratory of Nanotechnology for Agribusiness—Embrapa Instrumentation—São Carlos-SP, where part of the experiment was performed.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors state that the present study was conducted in the absence of commercial or financial relationships that could result in a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Albrecht MA, Evans CW, Raston CL. Green chemistry and the health implications of nanoparticles. Green Chem. 2006;8:417. doi: 10.1039/b517131h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amenta V, Aschberger K, Arena M, et al. Regulatory aspects of nanotechnology in the agri/feed/food sector in EU and non-EU countries. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;73:463–476. doi: 10.1016/J.YRTPH.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagherzadeh Homaee M, Ehsanpour AA. Physiological and biochemical responses of potato (Solanum tuberosum) to silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate treatments under in vitro conditions. Indian J Plant Physiol. 2015;20:353–359. doi: 10.1007/s40502-015-0188-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biemelt S, Keetman U, Albrecht G. Re-aeration following hypoxia or anoxia leads to activation of the antioxidative defense system in roots of wheat seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1998;116(2):651–658. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox A, Venkatachalam P, Sahi S, Sharma N. Silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticle toxicity in plants: a review of current research. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;110:33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvjetko P, Milošić A, Domijan A-M, et al. Toxicity of silver ions and differently coated silver nanoparticles in Allium cepa roots. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2017;137:18–28. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a guide for its bootstrap procedures in multiple comparisons. Ciência e Agrotecnologia. 2014;38:109–112. doi: 10.1590/S1413-70542014000200001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler-Lee J, Wang Q, Yao Y, et al. Phytotoxicity, accumulation and transport of silver nanoparticles by Arabidopsis thaliana. Nanotoxicology. 2012;7:323–337. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2012.658094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler-Lee J, Brooks M, Gerfen J, et al. Reproductive toxicity and life history study of silver nanoparticle effect, uptake and transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nanomaterials. 2014;4:301–318. doi: 10.3390/nano4020301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis CN, Ries SK. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:309–314. doi: 10.1104/PP.59.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havir EA, McHale NA. Biochemical and developmental characterization of multiple forms of catalase in tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:450–455. doi: 10.1104/PP.84.2.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homaee MB, Ehsanpour AA. Silver nanoparticles and silver ions: Oxidative stress responses and toxicity in potato (Solanum tuberosum L) Grown in vitro. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2016;57:544–553. doi: 10.1007/s13580-016-0083-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H-S, Yin L-Y, Ren N-N, et al. Silver nanoparticles induced reactive oxygen species via photosynthetic energy transport imbalance in an aquatic plant. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11:157–167. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1278802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y, Metreveli G, Park C-B, Baik S, Schaumann GE. Implications of pony lake fulvic acid for the aggregation and dissolution of oppositely charged surface-coated silver nanoparticles and their ecotoxicological effects on Daphnia magna. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:436–445. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b04635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaveh R, Li Y-S, Ranjbar S, Tehrani R, Brueck CL, Aken BV. Changes in Arabidopsis thaliana gene expression in response to silver nanoparticles and silver ions. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(18):10637–10644. doi: 10.1021/es402209w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ke M, Zhang M, et al. The interactive effects of diclofop-methyl and silver nanoparticles on Arabidopsis thaliana: growth, photosynthesis and antioxidant system. Environ Pollut. 2018;232:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo S-L, Krantz WB, Fane AG, Gao Y, Lim T-T, Hu X. Bactericidal mechanisms revealed for rapid water disinfection by superabsorbent cryogels decorated with silver nanoparticles. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:2310–2318. doi: 10.1021/es5048667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura MR, Mattoso LHC, Zucolotto V. Development of cellulose-based bactericidal nanocomposites containing silver nanoparticles and their use as active food packaging. J Food Eng. 2012;109:520–524. doi: 10.1016/J.JFOODENG.2011.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nair PMG, Chung IM. Chemosphere physiological and molecular level effects of silver nanoparticles exposure in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. Chemosphere. 2014;112:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22:867–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien TP, Feder N, McCully ME. Polychromatic staining of plant cell walls by toluidine blue O. Protoplasma. 1964;59:368–373. doi: 10.1007/BF01248568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey C, Khan E, Mishra A, Sardar M, Gupta M. Silver nanoparticles and its effect on seed germination and physiology in Brassica juncea L. (Indian Mustard) plant. Adv Sci Lett. 2014;20:1673–1676. doi: 10.1166/asl.2014.5518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel LR, Dubey B. Evaluation of developmental responses of two crop plants exposed to silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Sci Total Environ. 2013;452–453:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad R, Bhattacharyya A, Nguyen QD. Nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture: recent developments, challenges and perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1014. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha N, Dutta Gupta S. Low-dose toxicity of biogenic silver nanoparticles fabricated by Swertia chirata on root tips and flower buds of Allium cepa. J Hazard Mater. 2017;330:18–28. doi: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmast MK, Niazi A, Salehi H, Abolimoghadam A. Silver nanoparticles affect ACS expression in Tecomella undulata in vitro culture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015;121:227–236. doi: 10.1007/s11240-014-0697-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J-P, Ma C-Y, Xu B, Zhang H-W, Yu C-P. Effect of light on toxicity of nanosilver to Tetrahymena pyriformis. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2012;31:1630–1638. doi: 10.1002/etc.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosan A, Svistunenko D, Straltsova D, et al. Engineered silver nanoparticles are sensed at the plasma membrane and dramatically modify the physiology of Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Plant J. 2016;85:245–257. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syu Y, Hung J-H, Chen J-C, Chuang H. Impacts of size and shape of silver nanoparticles on Arabidopsis plant growth and gene expression. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;83:57–64. doi: 10.1016/J.PLAPHY.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timoteo CO, Paiva R, Reis MV, et al. Silver nanoparticles on dragon fruit in vitro germination and growth. Plant Cell Cult Micropropag. 2018;14(1):18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Timoteo CO, Paiva R, Reis MV, et al. Silver nanoparticles in the micropropagation of Campomanesia rufa (O. Berg) Nied. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11240-019-01576-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A, Liu S, Singh PK, et al. Differential phytotoxic responses of silver nitrate (AgNO3) and silver nanoparticle (AgNPs) in Cucumis sativus L. Plant Gene. 2017;11:255–264. doi: 10.1016/J.PLGENE.2017.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi DK, Singh S, Singh S, et al. Nitric oxide alleviates silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) induced phytotoxicity in Pisum sativum seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;110:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkevich J, Stevenson PC, Hillier J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1951;11:55. doi: 10.1039/df9511100055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vance ME, Kuiken T, Vejerano EP, et al. Nanotechnology in the real world: redeveloping the nanomaterial consumer products inventory. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2015;6:1769–1780. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.6.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Koo Y, Alexander A, et al. Phytostimulation of poplars and Arabidopsis exposed to silver nanoparticles and Ag+ at sublethal concentrations. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:5442–5449. doi: 10.1021/es4004334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X-F, Liu Z-G, Shen W, Gurunathan S. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, properties, applications and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1534. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuverza-mena N, Armendariz R, Peralta-videa JR, Gardea-Torresdey JL. Effects of silver nanoparticles on radish sprouts: Root growth reduction and modifications in the nutritional value. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]