Abstract

We report integration of the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA) United States Environmental Justice Screen (EJSCREEN) database with our Public Health Exposome dataset to interrogate 9232 census blocks to model the complexity of relationships among environmental and socio-demographic variables toward estimating adverse pregnancy outcomes [low birth weight (LBW) and pre-term birth (PTB)] in all Ohio counties. Using a hill-climbing algorithm in R software, we derived a Bayesian network that mapped all controlled associations among all variables available by applying a mapping algorithm. The results revealed 17 environmental and socio-demographic variables that were represented by nodes containing 69 links accounting for a network with 32.85% density and average degree of 9.2 showing the most connected nodes in the center of the model. The model predicts that the socio-economic variables low income, minority, and under age five populations are correlated and associated with the environmental variables; particulate matter (PM2.5) level in air, proximity to risk management facilities, and proximity to direct discharges in water are linked to PTB and LBW in 88 Ohio counties. The methodology used to derive significant associations of chemical and non-chemical stressors linked to PTB and LBW from indices of geo-coded environmental neighborhood deprivation serves as a proxy for design of an African-American women’s cohort to be recruited in Ohio counties from federally qualified community health centers within the 9232 census blocks. The results have implications for the development of severity scores for endo-phenotypes of resilience based on associations and linkages for different chemical and non-chemical stressors that have been shown to moderate cardio-metabolic disease within a population health context.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11524-018-00338-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Particulate matter 2.5 μm, United States Environmental Protection Agency, United States Environmental Justice Screen, Low birth weight, Pre-term birth, Infant mortality, Cardiovascular, CV, Cardiovascular disease, Public participatory geographical information system, Toxic release inventory facility

Introduction

While Columbus, Ohio, is considered one of the more prosperous, well-educated, and progressive neighborhoods in the United States, it presents with some of the highest levels of all-cause mortality in the country [1]. The census tracks that are home to these excessive rates of mortality are located within the Southern Gateway neighborhoods [2]. The Southern Gateway represents a collection of neighborhoods on the south side of Columbus and includes the following neighborhoods: Hungarian Village, Reeb-Hosak, Merion-Village South, Innis Gardens, Vasser Village, and Stambaugh Elmwood. These neighborhoods represent varying degrees of health-related vulnerability stemming from a number of social and economic challenges ranging from sub-standard housing to low levels of educational attainment, infant and maternal health, proximity to toxic releases, proximity to traffic-related pollution, and other neighborhood stressors, such as crime, violence, and poverty [2, 3]. The Parsons corridor, which bisects the community, was once served by multiple street car lines and has been the primary commercial corridor serving generations of immigrants to Columbus, including European immigrants in the early twentieth century, African-American migrants escaping Jim Crow in the mid-twentieth century, and Appalachian migrants from Kentucky and West Virginia in recent decades [3]. At the time, Buckeye Steel (now known as Columbus Castings) was a primary employer, providing employment opportunities for thousands of south side residents and immigrants [3].

In the past four decades, the Southern Gateway neighborhoods have experienced extreme social and economic distress—most notably, depopulation, housing decay, rising rates of crime, and a loss of relatively well-paying manufacturing jobs. During much of the second half of the twentieth century, Columbus Castings employed a significant portion of Southern Gateway residents, but as of 2018, this neighborhood had lost a significant portion of its industrial base, which employed many of its residents, due largely to automation and globalization. Thus, since the 1970’s poverty, unemployment, crime, and housing blight have increased in many of the neighborhoods surrounding Parsons Avenue. Several businesses and residences along the corridor are vacant and severely dilapidated [3]. The effects/impacts of these overarching social trends were made even worse due to sub-prime lending activities that precipitated the 2008 housing crisis, producing widespread foreclosures throughout the area bringing additional blight and arson risks. The housing-related impacts/downturns of the Great Recession have been shown to acerbate health disparities, particularly among high-poverty, predominantly non-White neighborhoods who were already facing some of the highest rates of morbidity and mortality in the nation [4]. As a community of concentrated disadvantage, the Southern Gateway neighborhoods exhibit many of the social, economic, built environment, and health challenges found in distressed areas of concentrated poverty throughout the nation [3]. Overall, the Southern Gateway neighborhoods are racially mixed, 70% White and 25% African-American, reflecting the mixed racial demographics of the greater Southside area, which is 50% White and 45% African-American [3].

The Stambaugh Elwood (SE) neighborhood, located in zip code 43207, is 95% African-American and zoned as a mixed-use area, combining residential, industrial, commercial, retail, and service land uses in conjunction/along with significant sources of manufacturing. In 2013, SE community leaders met with environmental public health scientists from The Ohio State University (OSU) to address concerns related to air and soil quality in their community, with specific inquiries concerning widespread environmental contamination. SE residents sought to develop a partnership with OSU environmental public health scientists through a pre-existing structure employed by the Columbus Public Health, the local health department. Through an ad hoc South Side Health Advisory Committee (SSHAC), a community-academic-local state agency partnership was conceived, designed, implemented, and tested. A study plan was developed, a public participatory geographical information system (PPGIS) was customized for SE residents, soil samples were analyzed, and the results were disseminated to SE residents via the PPGIS portal [2]. The study was conducted over a 17-month period and demonstrated that community-led coalitions in collaboration with academia and local public health policy-making officials can effectively address the environmental concerns of residents in high-risk neighborhoods [2].

The Ongoing Problem

The leading causes of infant mortality (IM) are known to be prematurity, low birth weight, congenital anomalies, and/or maternal complications during pregnancy [33]. Racial disparities persist for all underlying causes of infant deaths, especially those due to prematurity or intrauterine growth retardation. Specifically, our results indicate that within the city of Columbus, overall IM rates as well as persistent racial disparities in this key indicator of population health are largely shaped by the unjust distribution of key social and economic conditions that vary dramatically across neighborhoods. Although IM is a major concern for Columbus, OH, the SE neighborhood is faced with a plethora of equally disparate health outcomes (Table 1). The SE community is located in zip code 43207 where the corresponding census blocks document an IM rate of 12.5 African-American infant deaths per 1000 live births [1]. Our overarching hypothesis for this line of research was that new environmental factors/variables can be identified and tested for association with disparate health outcomes in high-risk neighborhoods. In the present study, we link longitudinal, geo-coded measures of LBW, and PTB with key socio-demographic and environmental risk factors by assessing multiple aspects of the built, natural, and physical environments of the (1) Southern Gateway neighborhoods, in particular, and the (2) Ohio neighborhoods, in general, toward identifying community-level chemical and non-chemical stressors and exposures associated with IM in Southern Gateway neighborhoods.

Table 1.

Summary of socio-demographic and health indicators in the Southern Gateway neighborhoods by zip code vs Franklin County, Columbus City, and the State of Ohio

| Source | 43206 | 43207* | 43209 | Franklin | Columbus | Ohio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 21,864b (22,162 ± 979)c | 45,144b (47,943 ± 161)c | 27,228b (27,934 ± 782)c | 1,163,414b (1,197,592 ± NA)c | 787,033b (811,943 ± 129)c | 11,536,504b (11,560,380 ± NA)c |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| African-American population (%) | 43.9b (44.3 ± 2.6)c | 26.2b (25.9 ± 2.1)c | 25.8b (27 ± 2)c | 21.2b (21.30 ± 0.2)c | 28b (27.80 ± 0.3)c | 12.2b (12.20 ± 0.1)c |

| Latino population (%) | 2.3b (2.4 ± 1.4)c | 3.4b (4.5 ± 1.2)c | 2.8b (2.9 ± 1)c | 4.8b (4.9 ± NA)c | 5.6b (5.70 ± 0.2)c | 3.1b (3.30 ± 0.1)c |

| Education | ||||||

| Education < 9th grade | 44a (4.4 ± 1.6)c | 7.5a (6.8 ± 1.5)c | 2.8a (1.7 ± 0.6)c | 34a (3.2 ± 0.2)c | 3.9a (3.80 ± 0.3)c | 3.6a (3.20 ± 0.1)c |

| Education up to high school | 30.6a (27.9 ± 2.6)c | 39.6a (42.3 ± 2)c | 18.5a (17.9 ± 2)c | 27.1a (25.5 ± 0.4)c | 27.3a (26.10 ± 0.5)c | 36.a (34.50 ± 0.1)c |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15.8a (21.2 ± 2.2)c | 4.1a (6.2 ± 0.9)c | 27.1a (28.4 ± 1.8)c | 21.2a (23.40 ± 0.3)c | 19.9a (21.80 ± 0.5)c | 13.7a (16.10 ± 0.1)c |

| Graduate education | 9.2a (12.3 ± 1.9)c | 1.4a (2.3 ± 0.5)c | 21a (23.6 ± 1.8)c | 10.7a (13.40 ± 0.2)c | 9.2a (11.50 ± 0.3)c | 7.5a (9.50 ± 0.1)c |

| Employment and income | ||||||

| Unemployed individuals > 16 years in civilian labor force | 4.5a (9.4 ± 1.4)c | 3.6+a (8.5 ± 1.3)c | 3.3a (4.3 ± 0.8)c | 3a (5.60 ± 0.2)c | 3.5a (6.20 ± 0.3)c | 3.2a (5.80 ± 0.1)c |

| Median household income (US dollars) | 34,794a (41,717 ± 2244)d | 34,287a (39,634 ± 2455)d | 46,016a (53,924 ± 3918)d | 42,734a (51,890 ± 447)d | 37,897a (44,774 ± 464)d | 40,956a (48,849 ± 162)d |

| Families below the poverty level (%) | 18.3a (24.7 ± 4.1)e | 12.7a (19.7 ± 2.8)e | 10.2a (11.8 ± 2.4)e | 8.2a (1320 ± 0.5)e | 10.8a (17.40 ± 0.7)e | 7.8a (11.70 ± 0.1)e |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Insured to health care (%) | 84.8 ± 2.2c | 83.1 ± 2.1c | 90.6 ± 1.4c | 87.60 ± 0.3c | 85.6 ± 0.4c | 89.10 ± 0.1c |

| Chronic health disease (IC 95%) | ||||||

| Diabetes/told they have diabetes (%) | 8.0g (1.3, 14.7) | 13.7g (5.4, 22.0) | 5Ag (0.7, 10.1) | 4.0f & 10.1g (8.8, 11.4) | 6.0f | |

| Obesity/overweight or obese (%) | 51.2g (32.6, 69.8) | 69.8g (59.5, 80.2) | 58.8g (41.6, 76.0) | 20.0f & 64.1g (61.9, 66.4) | 22.0f | |

| Current asthma (%) | 5.9g (0.0, 11.7) | 16.6g (9.0, 24.2) | 7Ag (0.0, 16.2) | 9.6g (8.3, 10.9) | ||

| Tobacco use/currently smoke (%) | 34.9g (17.6, 52.2) | 34.6g (23.7, 45.4) | 18.2g (1.4, 35.0) | 13.0g & 22.14 (20.1, 24.2) | 29.0f | |

| Ever told had depressive disorder (%) | 16.2g (4.4, 28.1) | 28.6g (18.3, 38.8) | 18.9g (6.2, 31.7) | 20.8g (18.9, 22.6) | ||

| Pregnancy and birth outcomes | ||||||

| Total number of births | 779g | 1274g | 734g | 38,053g | ||

| Low birth weight (%) | 11.9g | 11.6g | 9.7g | 9.0g | ||

| Preterm births (%) | 13.1g | 12.6g | 10.6g | 10.5g | ||

| Teenage mothers (%) | 4.1g | 2.7g | 0.1g | 1.5g | ||

| Infant mortality rate (2010–4) | 10.9g | 12.5g | –h | 8.4g | ||

| Health promotion and disease prevention | ||||||

| Walk Score ® | 70g | n/a | 26g | 40g | ||

| Food imbalance (%) | 14.8g | 36.7g | 61.2g | 23.9g | ||

| Sexually transmitted infections (cases (per 100,000)) | ||||||

| Chlamydia | 386 (1741.7)g | 502 (1047.1)g | 205 (733.9)g | 9441 (788.3)g | ||

| Gonorrhea | 174 (785.1)g | 178 (371.3)g | 76 (272.1)g | 3265 (272.6)g | ||

| Leading causes of death (cases; ADR (95% CI)) | ||||||

| Heart disease | 94; 169.6 (137.1, 207.6)g | 341; 232.5 (207.6, 257.4)g | 143; 125.1 (103.9, 146.3)g | 5623; 173.5 (168.9, 178.1)g | ||

| Cancer | 101; 169.9 (135.3, 204.5)g | 317; 209.9 (186.6, 233.2)g | 135; 130.7 (108.0, 153.4)g | 5729; 172.3 (167.7, 176.8)g | ||

| Stroke | 27; 54.5 (35.9, 79.3)g | 83; 58.4 (46.5, 72.4)g | 49; 44.1 (32.6, 58.3)g | 1361; 43.3 (41.0, 45.6)g | ||

| Chronic lower respiratory disease | 42; 74.4 (53.6, 100.6)g | 130; 89.5 (74.0, 105)g | 26; 23.5 (15.4, 34.5)g | 1539; 48.3 (45.8, 50.8)g | ||

| Diabetes | 19; 32.6h (19.6, 50.8)g | 60; 41.1 (31.4, 53)g | 11; 11.0h (5.5, 19.7)g | 868; 26.1 (24.3, 27.9)g | ||

| Accident/unintentional injury | 37; 56.4 (39.7, 77.7)g | 108; 75.4 (61.0, 89.7)g | 27; 29.2 (19.3, 42.5)g | 1485; 41.6 (39.5, 43.8)g | ||

| Homicide | 17; 24h (14.0, 38.5)g | 33; 24.5 (16.8, 34.3)g | 8; 10.2h (4.4, 20.2)g | 305; 8.1 (7.2, 9.0)g | ||

| Suicide | 12; 18.2h (9.4, 31.9)g | 26; 18.4 (12.0, 27.0)g | 11; 12.3h (6.1, 22.0)g | 427; 11.7 (10.6, 12.8)g | ||

a2000 Census

b2010 Census

c2014 American Community Survey

dSampling estimations have (± 95% MOE); inflation adjusted to 2014 dollars

eAccording to income in the last 12 months

fFranklin County Health Map 2016

gColumbus Public Health—CPH Epi program

hValues must be interpreted carefully

Vulnerable populations are likely to live within a mile of a toxic release inventory (TRI) facility [5–11]. A direct association was evident between the presence of TRI facilities and a high-percentage non-White residents and an inverse association between the number of TRI facilities and high socio-economic status (SES) [5]. Using the 2000 census data, a previous study documented evidence of socio-demographic disparities in the location of TRI facilities and chemical releases in Atlanta, GA [5]. As the percentage of college graduates increased, the odds of that census tract having a TRI facility decreased, controlling for median household income, percent of Hispanic population, and percent of Black population [5]. Tracts with a high percentage (> 50%) of lower-middle class residents ($22,500–$55,000 household income) had more TRI facilities than more affluent tracts (p = 0.05) [5]. Moreover, 59% of the TRI facilities were found in lower-middle class census tracts. Therefore, environmental variables of potential interest include proximity to locations, such as toxic release inventory [TRI] sites [5], facilities with risk management plans [5], retail tobacco outlets [6], high traffic-related pollution roadways [10], and residential soil metalloid levels [2].

All of these data suggest an association of TRI facilities with high-risk neighborhoods and perhaps a marker for neighborhood deprivation.

The Solution

Our novel and innovative Public Health Exposome framework uses systems theory, trans-disciplinary constructs, and a life course perspective to discover how place-based social and economic factors in combination with chemical and non-chemical environmental exposures affect individual health outcomes and lead to population-level disparities across time and space [6]. Research presented here will close the gap between research conducted on the eco-exposome (individual and general external environments) and research focused on the endo-exposome (internal environment) [12]. The Public Health Exposome framework will allow for the development of cumulative risk models that estimate the role of which exposure(s) to multiple, chemical (PM2.5), and non-chemical (sub-standard housing, violence, neighborhood deprivation) stressors over the life course produce endo-phenotypes that modify the incidence of adverse health events, or alternatively resilience, at the population level. This approach holds great promise for increasing our understanding of exposure mechanisms and pathways associated with adverse health outcomes and for identifying the effects of different levels of exposure at critical life stages [6, 13]. It serves as a template for targeting clinical, program, and policy initiatives that address the needs and circumstances of vulnerable populations and neighborhoods. Most of the research generated by an exposome approach has focused on the endo-exposome-internal biological exposure pathways and mechanisms that focus on genetics and omics technologies [12]. The majority of this research examined the effects of exposures on endogenous processes of the body, such as metabolism, circulating hormones, gut microflora, inflammation, lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, and aging. Failure to link exposures in the eco-exposome (i.e., external environment) to observed molecular profiles of those exposures, however, will severely dampen the ability to translate and apply research findings to environmental public health policy [12].

Methods and Materials

Decision Support Tools for Citizen Science-Led Community Mapping and Hazard Identification

A Public Participatory Geographical Information System (PPGIS) portal was developed and customized for the Southern Gateway community of Stambaugh Elwood that was built on our Public Health Exposome database platform powered by MapplerX. Subsequent to the development and customization of this PPGIS portal by the Division of Environmental Health Sciences, College of Public Health, in April 2014, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) launched the United States Environmental Justice Screen (EJSCREEN) in June 2015 [14]. Like MapplerX, EJSCREEN is an interactive mapping tool that enables residents of Southern Gateway neighborhoods in Columbus, OH, to access public and private databases to assist in identifying neighborhoods that may have environmental concerns. The USEPA’s tool EJSCREEN combines environmental and demographic indicators to create twelve environmental justice indices. The data include pollution exposure estimates and are able to show population proximity to industrial or facility locations. This comprehensive tool enables users to access a variety of data. However, it is important to note that EJSCREEN is not to be used as a risk assessment tool. Rather, it can highlight areas of interest that may be burdened by environmental disturbances and health disparities. Since EJSCREEN maps can provide data at the local level, they provide the much-needed attention to vulnerable neighborhoods that need further scientific review and analysis for potential policy review and change.

The SE community of Columbus, Ohio (n = 150), is located within the zip code 43207. Use of the USEPA’s tool EJSCREEN indicates that this community is approximately 90–95% in close proximity to a facility requiring a risk management plant (RMP) [2]. Under the Clean Air Act, facilities that use environmental contaminants and hazardous substances are required to have an RMP on file. For residents living in neighborhoods in close proximity to these facilities, it is possible that contaminant emission and hazardous outputs are contributing factors to the observed disparate health outcomes within the community [2].

Southern Gateway Community Health Indicators Included in the PPGIS Portal

Health indicator data provided in the portal developed for the SE community is shown in Table 1 and includes the following: (1) Ohio health data from the Ohio Department of Health database; (2) sub-county-level gridded (3-km) PM2.5 data from the US Research Administration database in Huntsville, AL [15]; (3) USEPA’s (Unites States Environmental Protection Agency) toxic release inventory (TRI) data and USEPA’s air data from approximately 13 industrial sites within the boundaries of Southern Gateway neighborhoods comprising zip codes 43206 and 43207; (4) census track/block and zip code data; and (5) land use and cover. An added feature for residents of high-risk neighborhoods is the ability to upload data specific to an individual’s place of residence.

Demonstration of Significant Associations between Pairs of Environmental and/or Socio-Demographic Factors/Variables

The p values for each association were calculated to derive an adjacency matrix representing significant associations between pairs of environmental and/or socio-demographic variables that are controlled by all remaining variables. The weighted adjacency matrix of the Bayesian network model contained all significant p values (< 0.05) for each link.

Data Curation and Bayesian Network Model

The units of observation in the secondary datasets used were census tracts. We used the standard identifiers to link both data sets. Data from the USEPA’s EJSCREEN is publicly available at the webpage. Data from the Ohio Department of Health was obtained upon request. Even though we used aggregated data by census tracts, we also requested IRB clearance. Secondary data sets available from the USEPA’s EJSCREEN website [14] and per request from the Ohio Department of Health were linked to 9232 census block standard identifiers in all Ohio counties and subjected to machine learning. Our network used the “Hill Climbing” with BIC criterion of the “bnlearn” package in R software [16]. Associations were developed and accounted for 32.85% density and an average degree of 9.2. Post hoc values of arrows (associations) are shown as p values based on linear conditional correlation, and line widths are highest for the lowest p values. Automatic visualization accounted for the relative value of the links (obtained by transforming p values by log-transformation and normalization/truncation from 5 to 1) by a mapping algorithm, followed by an energy-based algorithm, available in Pajek software which located more connected nodes in the center of the graph.

Results

Table 1 details the many variables and factors that contribute to an individual’s quality of life. They are collectively referred to as the social determinants of health as defined by the World Health Organization [1]. The social determinants of health include, but are not limited to, “the social and economic environment, the physical environment, and the person’s individual characteristics and behaviors.” Addressing these determinants of health improves the quality of life of neighborhoods and reduces health disparities [17]. A dramatic consequence of health inequities is the significant divide in health outcomes in minority neighborhoods as compared to White neighborhoods. For instance, Latino neighborhoods are 65% more likely to have diabetes compared to their White counterparts [17]. When evaluating the social determinants of health shown in Table 1, several areas of concern have been identified in the Southern Gateway neighborhoods of Columbus, Ohio.

A major factor in consideration of an individual’s “quality of life” is socio-economic status [17]. Socio-economic status can be thought of as the product of educational attainment, occupational status, income, and/or wealth accumulation and can be assessed at multiple levels of exposure (individual, family, neighborhood, etc.) At the neighborhood level, these dimensions of SES interact to define the social standing of the community and predict a host of critical population health outcomes [35]. Moreover, aggregate measures of SES do not simply reflect the social and economic characteristics of community members. Place-based SES indicators have been shown to independently shape/influence the unequal distribution of health, above and beyond that which is attributed to individual-level SES indicators [36]. Thus, low SES neighborhoods tend to be classified as vulnerable high-risk neighborhoods—both as a direct result of the low level of socio-economic resources available to their residents and as an indirect indicator that these individuals are more likely to encounter health-compromising exposures as they go about their daily lives in these underfunded neighborhoods. Most importantly, for the current study, low SES neighborhoods and their requisite populations tend to encounter more frequent and more deleterious environmental contaminant stressors. What is unclear from the existing literature is the extent to which these environmental challenges/exposures/risk factors provide a viable mediating pathway through which racial disparities in birth outcomes can be explained.

To this end, we find empirical evidence in support of the primary/overarching hypothesis of this study—that low SES neighborhoods experience higher rates of LBW and PTB, in part, due to more frequent exposures to environmental contaminants. Given that these two outcomes are two of the strongest proximate determinants of infant mortality [37], it follows that elevated rates of infant mortality would follow similar trends. Furthermore, our results suggest that the linkages between neighborhood-level socio-economic status (SES), environmental exposures, and adverse birth outcomes are robust to other potential confounders, particularly maternal health behaviors and access to health care. Adverse birth outcomes are thought to be associated and linked to potential environmental contaminant stressors and exposures and, as suggested by the data presented here, may impact preterm birth conditions [17].

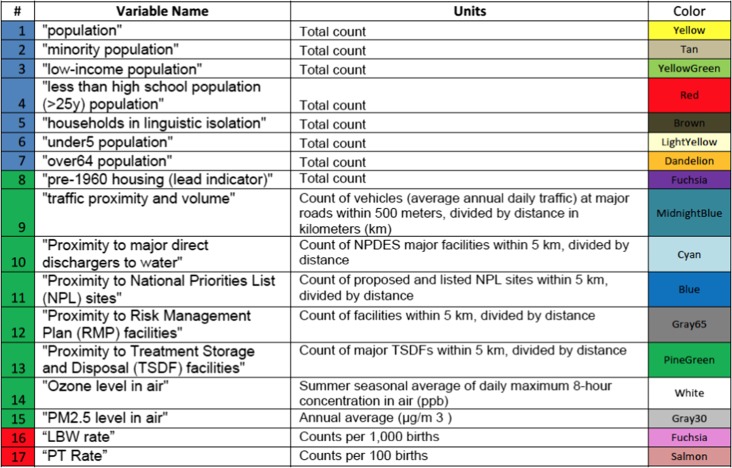

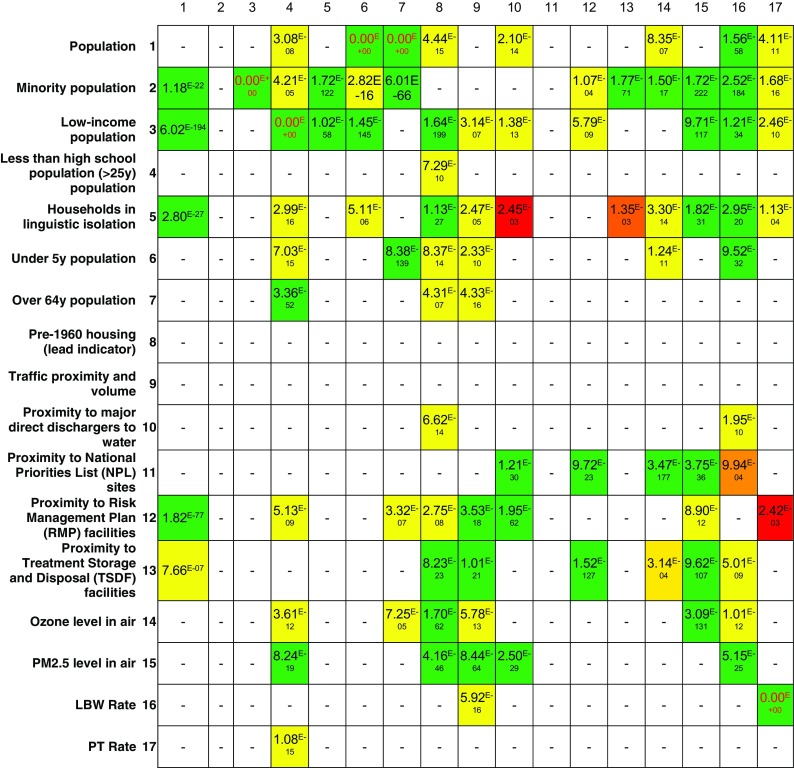

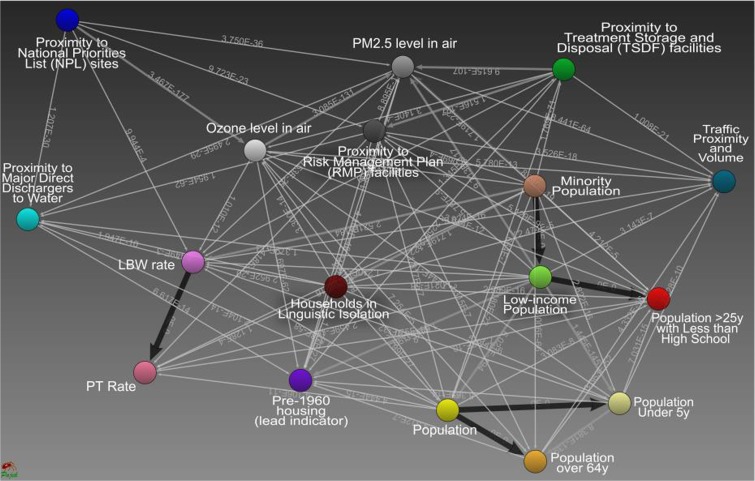

A significant outcome from this study is the identification and conformation of a previously undescribed set of environmental and socio-demographic neighborhood characteristics (factors and variables) that can be used as a Public Health Exposome neighborhood deprivation index for classifying high-risk neighborhoods. Table 2 shows the environmental and socio-demographic variables/factors modeled from all 88-counties in Ohio using the Public Health Exposome 3.0 database when linked to the USEPA’s EJSCREEN secondary data for the infant and maternal health outcomes, LBW and PTB. This included 7 socio-economic variables, 8 environmental variables, and 2 infant and/or maternal health outcomes that were reported for 9232 Ohio census blocks. All variables were continuous. Figure 1 shows an adjacency matrix to demonstrate significant associations between pairs of environmental and/or socio-demographic factors/variables. Figure 2 is a representation of the Bayesian network inferred from census track data modeling the complexity of relationships among socio-economic and environmental variables with the infant and maternal health outcomes (PTB and LBW) in all 88 Ohio counties. The model shown in Fig. 2 predicts that socio-economic variables (1) low income (green), (2) minority (tan), and (3) under age 5 (light yellow) populations are correlated and associated with environmental variables (7) PM 2.5 level in air (gray 30), (8) proximity to risk management facilities (gray 65), and (9) proximity to direct discharges in water (cyan). This Bayesian network model demonstrates the link between environmental and socio-demographic variables with pre-term birth and low birth weight within 88 counties in Ohio.

Table 2.

Environmental and socio-demographic variables with infant and maternal health outcomes (LBW and PT) modeled from all 88 counties in OH using the Public Health Exposome 3.0 database, Ohio Department of Health data, and the USEPA’s EJSCREEN secondary data

Fig. 1.

Adjacency matrix of the Bayesian network demonstrating the association between environmental variables and socio-demographic variables. The weighted adjacency matrix of the Bayesian network contains all significant p values (< 0.05) for each link. These p values represent significant associations between pairs of environmental and/or socio-demographic variables that are controlled by all remaining variables

Fig. 2.

Modeling the complexity of relationships among socio-economic and environmental variables. In this Bayesian network model, we included socio-economic and environmental variables that were reported for 9232 census blocks in Ohio. All variables were continuous. The model predicts that the socio-economic variables low income (green), minority (tan), and under age 5 (light yellow) together with environmental variables PM2.5 level in air (gray), proximity to facilities with a risk management plan (gray 65), and proximity to direct discharges in water (cyan) are associated with LBW and PTB

At the census block level, data from 1) Public Health Exposome 3.0 database, 2) EJSCREEN data, and 3) Ohio Department of Health data, predicts that socioeconomic variables were linked and associated with environmental variables and that both were correlated to the maternal health outcomes, PTB and LBW. Figure 2, adding to the link between PTB (salmon) and LBW (fuchsia) rates at the census track/block group levels, revealed significant controlled associations between PTB rates and educational attainment less than high school in people aged more than 25 years (red), minority and low-income populations (tan), and household in linguistic isolation (brown) and a weaker relationship with proximity to risk management plan (RMP) facilities (gray 65). LBW (fuchsia) rates had strongly controlled associations with traffic proximity (midnight blue), PM2.5 levels in air volume (gray30), minority and low-income populations (tan), and households in linguistic isolation (brown). Weaker associations were found with proximity to major direct dischargers to water (cyan), proximity to national priorities list (NPL) sites (blue), proximity to RMP facilities (gray 65), proximity to treatment storage and disposal (TSDF) facilities (pine green), and ozone level in air (white).

Discussion

The summary shown in Table 1 highlights the socio-economic and health indicators in high-risk neighborhoods with zip codes 43206, 43207, and 43209, which have the most problem, relative to Franklin County, Columbus City, and the State of Ohio. The social determinants of health for high-risk neighborhoods include factors, such as education, employment and income, pregnancy and birth outcomes, inadequate income, access to healthy foods, transportation, proximity to sources of pollution, jobs, stable housing, and access to health care. Families with barriers to these life-enhancing resources are at an increased risk of losing a child before his/her first birthday. Here, Black families are disproportionately and negatively affected by high rates of poverty, unemployment, and low educational attainment [34]. It is known that underrepresented minority populations with low income are likely to live within a mile of a toxic release inventory (TRI) facility [2, 4, 18]. Direct associations have been documented between the presence of TRI facilities and a high percentage of non-White residents, while inverse associations have been found between number of TRI facilities and high SES [18]. Conventional analyses have yet to derive an association between potential exposure to environmental contaminants and the disparate health outcomes observed in major metropolitan municipalities, such as Charleston, SC, Charlotte, NC, and Columbus, OH. The studies described here for Columbus, OH, address these gaps by employing emergent, highly innovative methodologies that have not previously been utilized to interrogate hypotheses germane to associations between adverse birth outcomes and high-risk neighborhoods [2].

The principal findings to emerge from the current study are two-fold. The first emphasizes that environmental risk factors, particularly proximity to locations, such as the TRI sites [4], facilities with risk management plans [5], air quality stations [6], retail tobacco outlets [5], and high traffic-related pollution roadways [10], as well as the environmental justice (EJ) index [14], can be used to identify and characterize high-risk neighborhoods via the Public Health Exposome framework. Rather than pitting socio-demographic predictors of health disparities against environmental exposures, the Public Health Exposome dynamically integrates these two key determinants of population health outcomes by emphasizing place-based mechanisms as well as life course processes. It is our hope that the inherently integrative nature of this framework will enhance our understanding of how the uneven distribution of neighborhood exposures, in combination with place-based vulnerability variables produce health inequalities in high-risk neighborhoods, including but not limited to excessive rates of infant mortality.

To this end, our findings suggest that effective efforts to improve birth outcomes, particularly among the most vulnerable populations, will need to expand their approach to consider environmental contaminants as critical pathways/mechanism through which these unequal health outcomes are produced and maintained across generations. Thus, integrating environmental health scientists as well as local and state policy-makers focused on these issues will be key to creating lasting solutions to long-standing disparities in infant health outcomes. Our results concerning the importance of environmental contaminants in shaping the unequal distribution of birth outcomes are even more critical when recalling that decades’ worth of research has not found other common proximate determinants of LBW and PTB, such as maternal smoking or access to prenatal care, to explain a substantial proportion of racial disparities in infant mortality [38].

Second, the health risks that minority populations face are not limited to those occurring at the beginning of the life course; instead, they also encounter elevated risks of other key drivers of adult mortality, including obesity, hypertension, and diabetes [39]. Additionally, many of the same neighborhood socio-demographic characteristics captured in the current study (SES, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, etc.) are associated with multiple key population health indicators—most notably, cardiovascular outcomes. Given the overlap between the distal determinants driving the unequal distribution of disease at the beginning and the end of life and that place-based exposures are considered to be fundamental causes of health inequalities [43], our findings are likely to be informative when designing public health interventions or policies to reduce levels of excess morbidity and mortality from other underlying causes. These additional applications of the Public Health Exposome are particularly critical because (1) public health interventions are not often tailored to vulnerable sub-populations and, thus, have limited efficaciousness and (2) large-scale epidemiological studies are cost-prohibitive and cannot be replicated across a wide variety of outcomes.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in light of a few important considerations. First, our analyses are based on data from the state of Ohio; thus, generalizability of the results presented here to other areas of the United States remains to be established by future research efforts. Second, our findings should, in no way, be interpreted to provide evidence of a causal connection between either key socio-demographic or environmental exposures and LBW or PTB. Although machine learning, in combination with Bayesian data analytic approaches, is a powerful statistical tool, they can only be used to establish correlations among a wide range of variables. Hopefully, subsequent studies will take advantage of longitudinal study designs and/or natural experiments to further identify the fundamental causes of racial disparities in perinatal outcomes. Finally, our two primary outcomes of interest in the current study are LBW and PTB. Given the limitations of the available data sources, we were unable to trace the linkages between key social, economic, and environmental exposures to our ultimate outcome of interest—infant mortality. We hope that future research will expand upon our findings by utilizing the Exposome Framework to explain and predict disparities in multiple health outcomes, including infant mortality, which are expressed at different life course stages.

Conclusion

The Public Health Exposome framework is a novel, geographic-based approach that incorporates data from a wealth of disparate sources and cutting-edge analytical approaches to understand how population health disparities emerge, with remarkable consistency across place as well as over time. By focusing on fundamental, as opposed to proximal, causes of health inequalities, our findings have identified new key environmental exposures, particularly the significant association of environmental factors and variables; proximity to facilities with risk management plans, proximity to major direct discharges to water, proximity to national priorities list sites, and proximity to treatment storage and disposal facilities with LBW and PTB. Equally important are the significant associations of socio-demographic factors and variables; minority population, low-income population, pre-1960 housing (lead indicator), and less than high school education with LBW and PTB. Furthermore, given the substantial overlap in socio-demographic characteristics that give rise to health disparities across the life course, our findings can and should be used to identify other effective public health approaches to reduce inequalities stemming from other health outcomes.

It is our hope that by recognizing environmental contaminants as key fundamental causes of health inequalities, we can design more effective interventions and policies to improve the health of some of the most vulnerable members of our society. For example, we are currently working on a project where we proposed a practical intervention for reducing Pb exposure and bioavailability in the blood. Measures of exposures to Pb and other environmental hazards are being collected from pregnant women residing in the Southern Gateway neighborhoods of Columbus, Ohio. Other measures of exposures to community-level stressors found in the natural, built, physical, and social environments are also gathered through multiple sources. Application of the PHE framework in intervention development is expected to uncover latent associations between environmental hazards and neurobehavioral deficits in the Southern Gateway pediatric population (ages 0–3). This project proposes to develop a population-level cumulative risk assessment model with severity scores for the risk of developing cardio-metabolic disease based on associations and linkages of chemical and non-chemical stressors. The severity score is meant to be used by clinicians and health care professionals at Federally Qualified Health Centers and inner-city safety net hospitals. Severity scores can also be used by local and state public health policy-makers to weigh the benefits and risks of exposures for better informed environmental public health policy.

Environmental exposure to chemical stressors, such as airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is strongly associated with increased morbidity and premature death from cardio-vascular disease (CVD) in exposed female African-American adults and those already suffering from a wide range of illnesses [19–28]. While this is particularly evident in environmentally compromised neighborhoods, globally, very little is known as to how chemical and non-chemical exposures from the natural, built, and social environment, coupled with individual behavioral and inherent characteristics, propagate the effects of PM2.5 on the lifetime progression of disparate cardio-metabolic health outcomes in longitudinal cohorts around the globe. In the future, the Public Health Exposome framework [6, 7, 13, 29] will advance understanding of associations between a combination of chemical and non-chemical stressor exposures, personal characteristics, and CMD risk in the cohorts of African-American women.

It is hoped that future studies will refine and expand upon findings from the seminal Jackson Heart Study, Black Woman’s Health Study, and the Cardia Study which developed risk prediction algorithms for coronary heart disease in a majority of African-American sample based on age, sex, cholesterol, smoking, and blood pressure [30]. Stress is a significant contributor to poor cardio-metabolic health and can be quantified as a function of allostatic load (psychological, environmental, and social measures) [31, 32]. In a multi-level manner, the work described here informs how to estimate exposure to chemical and non-chemical stressors from indices of neighborhood deprivation, environmental factors/variables, individual responses to surveys, and for a sample of participants, from biomarkers to be assayed from blood specimens provided at cohort entry. The signaling pathways responsible for the initiation of CVD processes over time are anticipated to be augmented in cohorts of African-American women, which predispose these systems to enhanced allostatic load [31, 32].

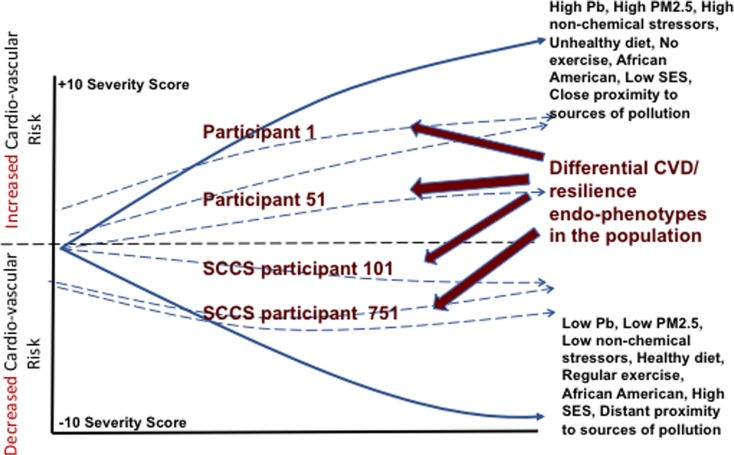

Application: Development of a Comparative Risk Model to Identify Endo-Phenotypes of Resilience

Originally developed in collaboration with the USEPA, the Public Health Exposome framework integrates a quantitative representation of risk that can be juxtaposed as endo-phenotypes of resilience as a function of exposure to chemical and non-chemical stressors (Fig. 3), with further moderation by health status, physical activity, SES, etc. The modeling of cumulative risks as a function of varied exposures requires a common dose-metric, so that the framework would assign ordinal severity scores of adversities (e.g., NOEL = 0; NOAEL = 1; LO(A) EL = 3, etc.), coupled with severity scores of benefit (none = 0, minimal = 1, moderate = 2, etc.), to create a common dose-metric for a benefit as well as the corresponding risk [40]. Severity scoring might be applied to variables associated with CVD based on strength of the association (semi-quantitative, expert judgment). The resulting scores would be multiplied by the available quantitative information (dose-response, from individual biomarker analysis in cohort participants) to yield a modified cumulative risk curve that incorporates all variables [41]. This approach might be applied to CVD outcomes by developing severity scores for associations and linkages for different non-chemical stressors, some of which might be expected to increase CVD in a population (e.g., low SES, poor diet, lack of exercise) as opposed to reducing CVD burden (good diet, exercise, access to health care). Each of these moderators might be expected to alter the trajectory of CVD, and each trajectory represents a unique endo-phenotype of resilience. Such a cumulative risk assessment approach would allow for the derivation of a CVD-specific index that weighs the benefits and risks of each factor. The expected result would be an evaluation of the contribution of chemical and non-chemical stressors (qualitatively and quantitatively) on a common cumulative risk and resilience scale, so that relative risks and/or corresponding resilience endo-phenotypes among differing factors could be compared [42].

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of a cumulative risk model at the population level that demonstrates how baseline incidence of cardiovascular risk might interact with chemical and non-chemical stressors. This example shows how in African-Americans, reducing PM2.5 exposure with a healthy diet, regular exercise, and socio-economic status may combine to decrease the overall risk of cardiovascular disease risk. Additionally, these differential trajectories might be contextualized as differential endo-phenotypes of resilience

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 5.09 mb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the entire Interdisciplinary Cardio-metabolic Exposome Team (ICE Tea) for critical review and comments. This work was supported, in part, by start-up package received from the Ohio State University College of Public Health and US EPA STAR Award RD83927501 (DBH and PDJ). Support was also from a start-up package received from Meharry Medical College for the Health Disparities Research Center of Excellence (PDJ).

Abbreviations

- PM2.5

Particulate matter at 2.5 μm

- USEPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

- EJSCREEN

United States Environmental Justice Screen

- LBW

low birth weight

- PTB

pre-term birth

- IM

infant mortality

- SE

Stambaugh Elwood

- SSHAC

South Side Health Advisory Committee

- CV

cardiovascular

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- PPGIS

public participatory geographical information system

- TRI

toxic release inventory

- RMP

risk management plan

- NPL site

national priorities list site

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Greater columbus infant mortality task force final report and implementation plan. Available online: http://gcinfantmortality.org/wp content/uploads/2014/01/IMTF-2014 Final-Report-v10.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2016.

- 2.Jiao Y, Bower JK, Im W, Basta N, Obrycki A-HM, Wilder A, Bollinger CE, Zhang T, Hatten L, Hatten J, Hood DB. Application of citizen science risk communication tools in a vulnerable urban community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(1):11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reece J, Olinger J, Holley K. Social capital and equitable neighborhood revitalization on Columbus southside. Available online: http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/01410-southside.pdf. Accessed 11 Aug 2015.

- 4.Burgard S, Kalousova L. Effects of the great recession: health and well-being. Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41(150504162558008):181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Angelo H, Ammerman A, Gordon-Larsen L, L Lytle L, Ribisl KM. Sociodemographic disparities in proximity of schools to tobacco outlets and fast-food restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1556–1562. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juarez PD, Matthews-Juarez P, Hood DB, Im W, Levine RS, Kilbourne BJ, Langston MA, Al-Hamdan MZ, Crosson WL, Estes MG, Estes SM, Agboto VK, Robinson P, Wilson S, Lichtveld MY. The public health exposome: a population-based, exposure science approach to health disparities research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(12):12866–12895. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111212866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langston MA, Levine RS, Kilbourne BJ, Rogers GL, Kershenbaum AD, Baktash SH, Coughlin SS, Saxton AM, Agboto VK, Hood DB, Litchveld MY, Oyana TJ, Matthews- Juarez P, Juarez PD. Scalable combinatorial tools for health disparities research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):10419–10443. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egli V, Oliver M, Tautolo e-S. The development of a model of community garden benefits to wellbeing. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzen H, Klein EG, Keller B, Hood N. Perceptions of physical inspections as a tool to protect housing quality and promote health equity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(2):549–559. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batterman S, Ganguly R, Harbin P. High resolution spatial and temporal mapping of traffic-related air pollutants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(4):3646–3666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120403646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Learn about the toxics release inventory. https://www.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program/learn-about-toxics-release-inventory (November 9).

- 12.Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005;14(8):1847–1850. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark RS, Pellom ST, Booker B, Ramesh A, Zhang T, Shanker A, Maguire M, Juarez P, Matthews-Juarez P, Langston M, Lichtveld M, Hood DB. Validation of research trajectory 1 of an exposome framework: exposure to benzo(a) pyrene confers enhanced susceptibility tobacterial infection. Environ Res. 2016;146:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EPA. EJSCREEN: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool. Available online: http://www2.epa.gov/ejscreen. Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 15.Al-Hamdan MZ, Crosson WL, Economou SA, et al. Environmental public health applications using remotely sensed data. Geocarto Int. 2014;29(1):85–98. doi: 10.1080/10106049.2012.715209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scutari M. Learning Bayesian networks with the bnlearn R package. J Stat Softw. 2010;35:1–22. doi: 10.18637/jss.v035.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healthy People 2020 [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx. Accessed 24 Apr 2017.

- 18.Ferguson KK, O'Neill MS, Meeker JD. Environmental contaminant exposures and preterm birth: a comprehensive review. J Toxicol Env Heal B. 2013;16:69–113. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2013.775048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters A. Particulate matter and heart disease: evidence from epidemiological studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207(2, Supplement):477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beelen R, Hoek G, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Stafoggia M, Andersen ZJ, Weinmayr G, Hoffmann B, Wolf K, Samoli E, Fischer PH, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Xun WW, Katsouyanni K, Dimakopoulou K, Marcon A, Vartiainen E, Lanki T, Yli-Tuomi T, Oftedal B, Schwarze PE, Nafstad P, de Faire U, Pedersen NL, Östenson CG, Fratiglioni L, Penell J, Korek M, Pershagen G, Eriksen KT, Overvad K, Sørensen M, Eeftens M, Peeters PH, Meliefste K, Wang M, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Sugiri D, Krämer U, Heinrich J, de Hoogh K, Key T, Peters A, Hampel R, Concin H, Nagel G, Jaensch A, Ineichen A, Tsai MY, Schaffner E, Probst-Hensch NM, Schindler C, Ragettli MS, Vilier A, Clavel-Chapelon F, Declercq C, Ricceri F, Sacerdote C, Galassi C, Migliore E, Ranzi A, Cesaroni G, Badaloni C, Forastiere F, Katsoulis M, Trichopoulou A, Keuken M, Jedynska A, Kooter IM, Kukkonen J, Sokhi RS, Vineis P, Brunekreef B. Natural-cause mortality and long-term exposure to particle components: an analysis of 19 European cohorts within the multi-center ESCAPE project. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(6):525–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pope Iii CA, Renlund DG, Kfoury AG, May HT, Horne BD. Relation of heart failure hospitalization to exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(9):1230–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelin TD, Joseph AM, Gorr MW, Wold LE. Direct and indirect effects of particulate matter on the cardiovascular system. Toxicol Lett. 2012;208(3):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polichetti G, Cocco S, Spinali A, Trimarco V, Nunziata A. Effects of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5 and PM1) on the cardiovascular system. Toxicology. 2009;261:1–2):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Link MS, Luttmann-Gibson H, Schwartz J, Mittleman MA, Wessler B, Gold DR, Dockery DW, Laden F. Acute exposure to air pollution triggers atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(9):816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson JL, Bild DE, Kronmal RA, Burke GL. Legacy of MESA. Glob Heart. 2016;11(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman JD, Adar SD, Barr RG, et al. Association between air pollution and coronary artery calcification within six metropolitan areas in the USA (the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Air Pollution): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2016;388(10045):696–704. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00378-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kaufman JD, Spalt EW, Curl CL, Hajat A, Jones MR, Kim SY, Vedal S, Szpiro AA, Gassett A, Sheppard L, Daviglus ML, Adar SD. Advances in understanding air pollution and CVD. Glob Heart. 2016;11(3):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunekreef B, Hoffmann B. Air pollution and heart disease. Lancet. 2016;388(10045):640–642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juarez PD, Hood DB, Rogers GL, Baktash SH, Saxton AM, Matthews-Juarez P, Im W, Cifuentes MP, Phillips CA, Lichtveld MY, Langston MA. A novel approach to analyzing lung cancer mortality disparities: using the exposome and a graph-theoretical toolchain. Environ Dis. 2017;2:33–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steptoe A, Hackett RA, Lazzarino AI, Bostock S, la Marca R, Carvalho LA, Hamer M. Disruption of multisystem responses to stress in type 2 diabetes: investigating the dynamics of allostatic load. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(44):15693–15698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410401111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The southern community cohort study: investigating health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):26–37. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee PA, Lamb S. A systematic review of factors linked to poor academic performance of disadvantaged students in science and math in schools. Cogent Educ. 2016;3:1. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1178441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamrath HJ, Osterholm E, Stover-Haney R, George T, O'Connor-Von S, Needle J. Lasting legacy: maternal perspectives of perinatal palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2018; 10.1089/jpm.2018.0303. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Weden MM, Carpiano RM, Robert SA. Subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics and adult health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1256–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hajat A, Diez-Roux AV, Adar SD, Auchincloss AH, Lovasi GS, O'Neill MS, Sheppard L, Kaufman JD. Air pollution and individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status: evidence from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(11–12):1325–1333. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schempf A, Strobino D, O’Campo P. Neighborhood effects on birthweight: an exploration of psychosocial and behavioral pathways in Baltimore, 1995–1996. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francisco A, El-Sayed A. National income inequality and ineffective health insurance in 35 low and middle income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:487–492. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braveman P, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S186–S196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dourson M, Price P, Unrine J. Health risks from eating contaminated fish. Comments Toxicol. 2002;8(4–6):399–419. 10.1080/08865140215061.

- 41.Anderson PD, Dourson M, Unrine J, Sheeshka J, Murkin E, Stober J. Framework and case studies. Comments Toxicol. 2002;8(4–6):431–502. 10.1080/08865140215066.

- 42.Hack CE, Haber LT, Maier A, Schulte P, Fowler B, Lotz WG, Savage RE., Jr Bayesian network model biomarker-based dose response. Risk Anal. 2010;30:1037–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;16(5):404–416. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 5.09 mb)