Abstract

Background

Differentiation between thalassemia major and thalassemia intermedia at presentation is not uniformly characterized, for which an absolute criteria needs to be developed. This study investigated the primary and secondary genetic modifiers to develop a laboratory finding by forming different genetic mutational combinations seen among thalassemia intermedia patients and comparing them with thalassemia major.

Methods

This cross‐sectional study analyzed 315 thalassemia intermedia patients. One hundred and five thalassemia major patients were recruited on the basis of documented evidence of diagnosis and were receiving blood transfusion therapy regularly. Various mutational combinations were identified, and comparison was performed between thalassemia intermedia and major using statistical software STATA 11.1.

Results

The mean age of the total population was 5.9 ± 5.32 years of which 165 (52%) were males. Of the two groups (thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia major), IVSI‐5, IVSI‐1, and Fr 8‐9 were more prevalent among the thalassemia intermedia cohort. When comparison was performed between the thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia major patients, it showed significant results for the presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism.

Conclusion

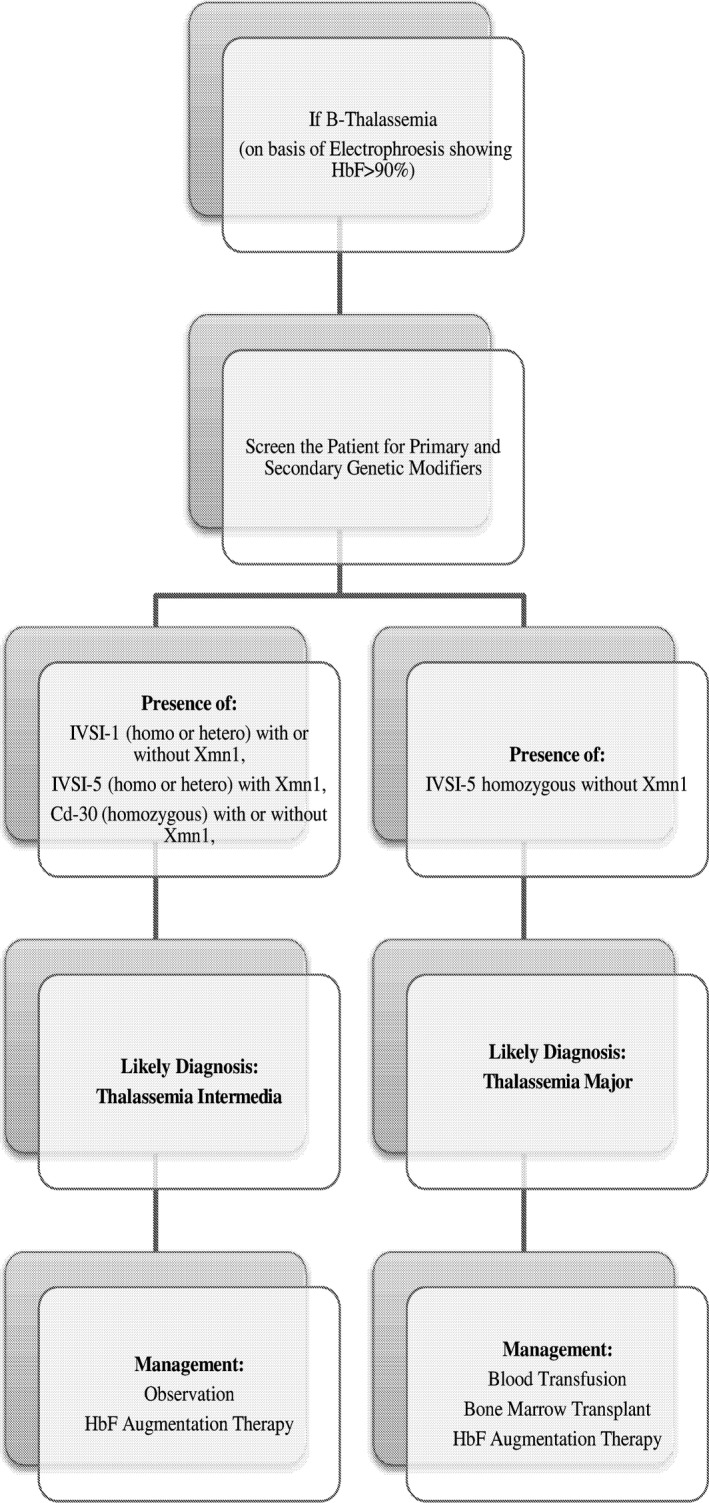

The presence of IVSI‐5 homozygous with Xmn‐1,IVSI‐5 heterozygous with Xmn‐1, Cd 30 homozygous with or without Xmn‐1 and IVSI‐1 homozygous or heterozygous either with or without Xmn‐1 prove to be strong indicators towards diagnosis of thalassemia intermedia.

Keywords: genetic modifiers, genetic mutational combinations, product transfusion, thalassemia, Xmn1 polymorphism

1. INTRODUCTION

Beta (β) Thalassemia is a group of diverse autosomal recessively inherited hemoglobin disorder with a prevalence of 80‐90 million carriers worldwide.1 About 60 000 symptomatic individuals are born annually, with a predominantly increased occurrence in the sub‐tropical and tropical regions, such as Mediterranean countries, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Southern Far East Africa, also known as the “Thalassemia Belt.”2, 3 In Pakistan, around 5000‐9000 children are born with β‐thalassemia every year, having an estimated carrier rate of 5%‐7%, with 9.8 million carriers in the total population.4, 5

β° thalassemia is characterized by the total deficiency of HbA (α2β2), due to the inheritance of two β° thalassemia alleles (compound heterozygous or homozygous states).This is termed as β‐thalassemia major, in which patients present with symptoms requiring transfusion dependency beginning from the first half of postnatal life.6 On the other end of the thalassemia spectrum is thalassemia minor(trait) in which there is presence of single β‐thalassemia allele, β+ or β°, in which there is increased Hb A2(α2δ2) without transfusion requirement.7

The third type, thalassemia intermedia, is also due to the inheritance of two β‐thalassemia alleles as in thalassemia major, but this condition is neither as severe as thalassemia major nor as mild as thalassemia trait.7, 8Such patients might present with anemia and usually require infrequent blood transfusion after the first 2 years of life.6 The thalassemia intermedia genotypically and clinically is a heterogeneous group of blood disorder. The severity could lie from the nonsymptomatic carrier state to the severe symptomatic state dependent on blood transfusion.6, 9, 10Approximately 5%‐10% of thalassemia intermedia patients could live without requiring any blood transfusion.11

The presence of the primary genetic mutations modifies the disease behavior and hence presents in a less severe form, due to which the primary genetic mutations could be acknowledged as a primary genetic modifier.12 In this study, we have investigated the primary and secondary genetic modifiers, to develop a laboratory finding by creating the commonest genetic combinations seen among thalassemia intermedia patients. This study could help to broadly quantify the diversity of thalassemia intermedia patients in the subcontinent, specifically Pakistan, and might help to draw evidence based guidelines for identifying the cohort patients who can be managed optimally without blood transfusion. This will also help for appropriate genetic counseling to the families in this region.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This cross‐sectional study analyzed a total of 315 patients, affected by thalassemia intermedia, attending the National institute of Blood Diseases (NIBD) from various regions of Pakistan since 2009. Other than the thalassemia intermedia patients, 105 thalassemia major patients were recruited as well. Approval for this study was granted by medical ethics committee of the institute. The procedure was explained, and an informed consent was obtained from each individual, and from parents of individuals younger than 18 years of age.

Patients were selected, based on their thalassemia‐specific clinical presentation (Hb = 3‐10gm/dL, age of presentation >2 years for intermedia while transfusion dependency beginning from <2 years for thalassemia major) in addition to Hb Electrophoresis and DNA mutation.13

Thalassemia intermedia and major cases having at least one of the genetic mutations or Xmn1 polymorphism missing from its data were removed during the analysis for genetic combination, of which 85 cases of intermedia and three cases of major were removed.

2.1. Laboratory parameters

2.1.1. Hematological analysis

On the basis of the complete blood count (CBC) investigation were obtained in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes and performed on Sysmex XE‐2100 hematology analyzer (Kobe, Japan). High‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)‐based Hb Electrophoresis (VARIANT II™ Hemoglobin Testing System, Bio‐Rad) was performed.

2.1.2. Biochemical analysis

At the time of presentation, serum creatinine, SGPT, and ferritin level were performed. The serum sample was collected in a red top vacutainer. For serum creatinine and SGPT, the test was performed on COBAS c111 (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd CH‐6343, Rotkreuz Switzerland) and serum Ferritin level was assessed using COBAS e411 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH D‐68298, Mannheim Germany).

2.1.3. Molecular analysis

DNA was extracted from the whole blood, using a DNA Purification kit (Genra system USA).

For detection of mutations, a PCR‐based method Multiplex ARMS was used. Primers were designed for simultaneous detection of the following mutations in a single reaction: IVSI‐5(G>C), Fr 8‐9 (+G), IVS 1‐1(G>T), Cd‐30(G>C), Cd‐5(‐CT), Del 619 bp, Cd‐15(G>A), Fr 41‐42(‐TTCT), Fr 16(‐C), and Cap +1(A>C).

Xmn‐1 polymorphism was determined by collecting 10 mL of blood in EDTA, and extracting the DNA. A 641 bp fragment of DNA, flanking C‐T polymorphism at −158 to the Gγ gene was amplified with primers. The amplified primers were digested overnight at 37°C with 20 units of Xmn‐1 restriction enzyme. After electrophoresing on 2% agarose gel and staining with ethidium bromide, the results were recorded.

2.2. Clinical parameters

Age of 1st transfusion and Hb level (g/dL), transfusion frequency (No. of Packed RBCs/year), mean volume (mL) of blood transfusion during whole life, spleen, and liver size (cm) were noted.

2.3. Statistical method

STATA version 11.1was used for data analysis.

3. RESULTS

Out of 307 thalassemia intermedia patients, 52% were males with mean age of 5.9 years.

Table 1 shows the comparison of laboratory and clinical parameters of thalassemia intermedia and major patients. Table 2 shows that among the two groups: IVSI‐5 and IVSI‐1 are more prevalent. Hence, just signifying the frequency of single mutations toward a genetic diagnosis of thalassemia intermedia could be misleading.

Table 1.

Thalassemia intermedia laboratory and clinical parameters

| Beta Thalassaemia Intermedia | Beta Thalassaemia Majora | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients |

Transfusion independent = 153 Transfusion dependantb = 154 |

105 |

| Hematological parameters | ||

|

Mean Hb(g/dL) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

Transfusion independent = 7.7 (7.5‐8.0) Transfusion dependantb = 7.4 (7.1‐7.8) |

5.6 (4.6‐6.6) |

|

Mean Hb F(%) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

Transfusion independent = 95.08 (93.4‐96.7) Transfusion dependantb = 93.5 (89.8‐97.3) |

92.9 (88.7‐97.1) |

| Biochemical parameters | ||

|

Mean Creatinine(mg/dL) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.4 (0.3‐0.5) |

|

Mean SGPT(μ/L) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

41.5 (31.5, 51.5) | 40.7 (5.8‐75.5) |

|

Mean ferritin(ng/mL) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

368.8 (253.2‐484.4) | 1496.1 (1155.5‐1836.6) |

| Clinical parameters | ||

|

Mean volume of blood transfused per year (mL) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

Transfusion dependantb = 821.3(674.7‐967.9) | 2412.5 (2152.2‐2672.7) |

|

Mean age of 1st transfusion(Y) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

4.1 (3.5‐4.7) | 2.2 (2.0‐2.7) |

| Liver and spleen size | ||

|

Mean liver size(cm) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

10.4 (9.9‐10.8) | 10.1 (9.6‐10.5) |

|

Mean spleen size(cm) (95% CI, lower bound‐upper bound) |

10.1 (9.4‐10.6) | 9.5 (6.5‐12.4) |

| Patients splenectomized | 25 | 37 |

>6 times transfusion per year.

Transfusion <6times per year.

Table 2.

Thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia major mutational cross‐tabulation

| Mutations | Thalassemia intermedia N = 307, N (%) | Thalassemia major N = 105, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| IVSI‐5 | 137 (44.6) | 64 (61) |

| IVSI‐1 | 48 (15.6) | 3 (2.9) |

| Fr 8‐9 | 37 (12.1) | 13 (12.3) |

| Cd 30 | 30 (9.8) | 3 (2.9) |

| Uncharacterized | 15 (5) | 2 (1.9) |

| Cd‐15 | 12 (4) | 3 (2.9) |

| Fr 41‐42 | 11 (3.6) | 6 (5.7) |

| Del‐619 | 9 (3) | 5 (4.8) |

| Cd 5 | 3 (0.9) | 4 (3.8) |

| Fr 16 | 3 (1) | 2 (1.9) |

| Cap +1 | 2 (0.65) | 0 (0) |

Cd, Codon; Del, Deletion; Fr, Frame shift; IVSI, Intervening segment I.

Table 3 identifies the commonest mutational combinations with the presence or absence of Xmn1 polymorphism toward the prediction of thalassemia intermedia. Table 4 shows significant results (P‐value<0.001) for the presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism in both groups.

Table 3.

Genetic combination comparison between thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia major

| Serial number | Genetic mutation combination | XMN (Present/Absent) | Thalassemia intermedia n (%) | Thalassemia major n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) | Del619, IVSI‐1 | Present | 8 (89) | 1 (11) | 9 |

| 2) | IVSI‐5, IVSI‐1 | Present | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 |

| 3) | IVSI‐5, Cd‐30 | Present | 7 (78) | 2 (22) | 9 |

| 4) | IVSI‐5, IVSI‐5 | Present | 33 (92) | 3 (8) | 36 |

| 5) | IVSI‐5, IVSI‐5 | Absent | 30 (38) | 50 (62) | 80 |

| 6) | IVSI‐1, IVSI‐1 | Present | 27 (90) | 3 (10) | 30 |

| 7) | Uncharacterized, Uncharacterized | Absent | 7 (78) | 2 (22) | 9 |

| 8) | Uncharacterized, Uncharacterized | Present | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 |

| 9) | Uncharacterized, IVSI‐5 | Present | 8 (89) | 1 (11) | 9 |

| 10) | IVSI‐5, Cd‐15 | Absent | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 |

| 11) | IVSI‐5, Cd‐15 | Present | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 |

| 12) | Cd‐30, Cd‐30 | Present | 15 (94) | 1 (6) | 16 |

| 13) | Cd‐30, Cd‐30 | Absent | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 |

Cd, Codon; Del, Deletion; IVSI, Intervening segment I.

Table 4.

The presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism among thalassemia intermedia and major patients

| Xmn‐1 polymorphism | Thalassemia intermedia N = 285 | Thalassemia major N = 105 | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xmn‐1 Absent |

118/285 41.4% |

87 82.9% |

<0.001 |

| Xmn‐1 Present |

167/285 58.6% |

18 17.1% |

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify patients with thalassemia intermedia on the basis of primary and secondary modifiers in Pakistan. It was found that thalassemia intermedia patients are likely to have particular types of mutations of the beta‐globin gene locus. Furthermore, it has also demonstrated that the Xmn‐1 mutation in the gamma‐globin gene promoter is associated with thalassemia intermedia patients at a higher rate in either homozygous or heterozygous state than those with thalassemia major.

In the developing world scenario, a significant number of thalassemia cases are frequented. However, if the timely diagnosis for thalassemia intermedia is not performed there remains a high probability of being started on continuous blood transfusion therapy immediately, which could lead to transfusion‐associated complications, that is iron overload, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and HIV, and as per studies 13%‐70% patients are prone toward these infections.14, 15 Keeping in view this background, specific primary and secondary genetic characteristics were investigated in this study toward the prediction of thalassemia intermedia.

4.1. Clinico hematological characteristics

About 49.8% of intermedia patients have always been transfusion independent, while 50.2% have been on transfusion dependent but still less than six packs per year in accordance with the definition. Similar to this study, Kaddah N et al16 reported 51.7% had no history of blood transfusion while 48.3% had history of blood transfusion. This is in agreement with Taher et al17 in which 52% received no blood transfusions, while 48% received infrequent blood transfusions.

Mean hemoglobin was 7.77 g/dL in transfusion independent and 7.4 g/dL in transfusion dependant intermedia patients. Our finding was in concordance with Kaddah AM et al16. Mean HbF of 93% with genetic characteristics of beta thalassemia is a confirmatory test for thalassemia syndrome. Our finding was in contrast to the results reported by Kaddah N et al16 with HbF ranged between 3.1 and 98 with a mean 26.47% and Qatanani et al18in which Hb F mean was 21.04%.

Mean volume of packed red cell transfused per year was 821.3 mL in intermedia, which is justified by the results reported by Taher et al19 as patients with thalassemia intermedia may benefit from an individually tailored transfusion regimen, compared with the regular transfusion regimens implemented in thalassemia major, to help prevent transfusion dependency. 2412.5 mL was the average packed red cell volume transfused per year in major patients. Liver and spleen size was enlarged but not massively. Mean serum ferritin of 368 ng/mL and 1496.19 ng/mL showed iron overload in intermedia patients and major patients, respectively. In patients with NTDT, intestinal absorption of iron can be as much as 3‐4 mg/d or 1000 mg/y.20, 21

4.2. Primary genetic modifiers

This study showed ten mutations (IVSI‐5, IVSI‐1, Fr 8‐9, CD‐30, Cap+1, Fr 41‐42, Fr 16, Del 619, CD 5, and CD‐15),which comprised of >90% of the genotype of the population, of which IVS1‐5, IVSI‐1, and Fr 8‐9 were the mutations that have shown to be associated with thalassemia intermedia which are therefore considered as primary genetic modifiers, which phenotypically show less severe phenotypic characteristics. Similar to our study, Karimi et al22 and Camaschella et al23 IVSI‐1mutation was found to be the most prevalent mutation within the thalassemia intermedia population. In contrast to our findings, Karimi et al22 reported IVSII‐1and IVSI‐110, with IVSII‐1 being the most common (24%) within the southern Irani intermedia population. Within the Mediterranean region, the commonest prevalent mutations for thalassemia intermedia included CD 39, IVSI‐110, and IVSI‐6.23A recent study performed in Pakistan by Khan, Ahmed et al24 in 2015 comprising of 63 patients showed that the most prevalent mutation among the thalassemia intermedia patients within Pakistan is IVSI‐5 but at the same instance they have also reported of identifying IVSII‐1 mutation. These studies showed diversity in mutations present among thalassemia intermedia patients within respective regions.

IVSI‐5 has been the most reported prevalent mutation within Pakistan among thalassemia intermedia patients, followed by IVSI‐1, CD 30, and Cap +1.24, 25 However, in our study, IVSI‐5 has been seen in both thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia major groups; hence, it could be said that thalassemia intermedia phenotype observed among patients carrying IVSI‐5 could be due to the secondary genetic modifiers. Uncertainty toward a probable genetic diagnosis of thalassemia intermedia further led us to analyze various mutational combinations for predicting thalassemia intermedia on the basis of its genetic mutations.24, 25

The genetic mutations, that is, IVSI‐5 and Cd 30 are the mutations that have been found to play a major role in affecting the phenotypic presentation of thalassemia patients and make them behave like intermedia. So the role of genetic mutations in terms of genetic modifiers has been discussed.

4.3. Genetic combinations

As the presence of certain gene mutation (IVS1‐5,IVS1‐1, Fr‐8‐9) was not significant toward the prediction of thalassemia intermedia, the mutations were then analyzed for the possible different genetic combinations (homozygous and heterozygous with or without Xmn‐1 polymorphism), which led to a more specific picture of the genetic mutations. This indicated that the presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism with certain mutational combinations was significant.

IVSI‐5 and IVSI‐I, either in homozygous or heterozygous conditions, were found to be prevalent among thalassemia intermedia only when Xmn‐1 polymorphism was present. IVSI‐5 in homozygous state without Xmn‐1 polymorphism was seen at a lower percentage (38%) and with the presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism was seen at a higher percentage (92%) within thalassemia intermedia patients (Table 3). This clearly highlights the fact that the presence of Xmn‐1 does play a significant role as a secondary genetic modifier among thalassemia intermedia patients.

For mutation Cd 30, in homozygous state, with either Xmn‐1 polymorphism present or absent was found to be exceedingly prevalent within the thalassemia intermedia cohort, hence, not giving any significance to the presence or absence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism. This specific mutation (Cd 30), however, will be required to be studied in more detail with a larger sample size. Similarly, the homozygous Uncharacterized mutations with Xmn‐1 polymorphism present or absent had higher proportion of thalassemia intermedia. In heterozygous state, Uncharacterized mutations were found to be abundant in thalassemia intermedia when found in combination with IVSI‐5.

The above discussion gives a prediction toward identifying thalassemia intermedia genetically on the basis of the mutations present in heterozygous or homozygous state, with or without Xmn‐1 polymorphism. This could help reaching an early diagnosis of intermedia and would help in preventing unnecessary blood transfusions among patients who are wrongfully labeled as thalassemia major (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnosis for thalassemia intermedia could be performed using the following flow diagram

4.4. Secondary genetic modifiers

The Xmn1 polymorphism, which acts as a secondary genetic modifier, was found in 58.6% of the thalassemia intermedia patients in our study. It has been seen that the Xmn1 polymorphism contributes toward ameliorating the phenotype as well.26 The thalassemia intermedia patients were compared to thalassemia major patients, which showed significant results (P‐value <0.001) for the presence of Xmn‐1 Polymorphism which is shown in Table 4. This justifies that the presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism creates an impact toward the hematological finding of the patients, specifically within the thalassemia major cohort, which clearly shows that within the thalassemia major patients, the presence of Xmn‐1 polymorphism is drastically less, due to which such patients might not be able to respond to hemoglobin augmenting agents therapy.

The above studies from Pakistan, India, Iran, and the Mediterranean region have shown a variation within the findings of the genotypic pattern between the countries, and, even between similar regions; however, our study is in a better position to provide a base for the primary screening of all diagnosed or suspected cases of thalassemia, which would lead toward not initiating blood transfusion therapy immediately but only on merit. This would lead toward understanding the magnitude of the problems in parts of the world where thalassemia is much more prevalent and the management and blood transfusion services are not of the required standard. Iron chelation therapy is expensive and out of reach of majority of patients, and the concept of comprehensive care does not exist within this part of the world. Therefore, identifying thalassemia intermedia at the baseline will help not only to reduce morbidity and mortality but also give a positive psychological and emotional support to the thalassemia community.

This is most likely the first study of its kind to investigate the genetic mutations with different combinations of primary and secondary genetic modifiers in Pakistan. The combination of these modifiers could play a role toward the genetic characterization of thalassemia intermedia.

This approach will also help thalassemia patients toward uptake of the Hb F augmentation therapy and also help in providing genetic counseling to the family. Eventually, it will help in reducing the financial burden as well, which would be saving approximately USD 3000/y/child. (Number of approximate thalassemia intermedia cases within Pakistan: 20 000, hence, 20 000 × 3000 = USD 60 000 000.)

5. CONCLUSION

The pivotal extract of this study is the significant presence of Xmn‐1polymorphism among thalassemia intermedia patients within Pakistan. The various genetic combinations discussed could be utilized toward an early detection for thalassemia intermedia or ruling out thalassemia major, which eventually could help prevent unnecessary blood transfusions. The results could form a basis toward identifying other genetic modifiers for beta‐thalassemia.

However, the strengths of this study are compromised by limitations. This study has focused exclusively on the findings of the genetic mutations rather than looking into the clinical and hematological characteristics of the thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia major patients. A need for further such studies with comparison of the clinical and hematological characteristics of the patients is required towards developing a more precise genetic diagnosis for thalassemia intermedia with a larger sample. This study could, however, act as a platform for further research as per this approach.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Dr. Ansari, Dr. Shamsi and Dr. Nadeem were responsible for the designing and idea of the research. Dr. Rashid and Dr. Khan contributed toward the epidemiological and statistical aspect of study. Dr.Rashid and Dr.Kaleem contributed toward the writing of the manuscript. Dr. Ansari and Dr. Jabbar were responsible for accumulating data and referring patients for the laboratory investigations. Dr. Hussain, Dr. Munzir, Dr. Hanifa, Dr. Kaleem, Dr. Naz, and Ms. Perveen contributed toward the laboratory aspects of the study.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The patients were enrolled into the study at NIBD & BMT. A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the use of clinical data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients, their parents to be part of study.

Ansari S, Rashid N, Hanifa A, et al. Laboratory diagnosis for thalassemia intermedia: Are we there yet? J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22647 10.1002/jcla.22647

REFERENCES

- 1. Galanello R, Origa R. Beta‐thalassemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chernoff AI. The distribution of the thalassemia gene: a historical review. Blood. 1959;14(8):899‐912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vichinsky EP. Changing patterns of thalassemia worldwide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1054(1):18‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahmed S, Saleem M, Modell B, Petrou M. Screening extended families for genetic hemoglobin disorders in Pakistan. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(15):1162‐1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ansari SH, Shamsi TS, Ashraf M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of β‐thalassemia in Pakistan: far reaching implications. Indian J Hum Genet. 2012;18(2):193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cao A, Galanello R. Beta‐thalassemia. Genet Med. 2010;12(2):61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thein SL. Pathophysiology of β thalassemia—A guide to molecular therapies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005;2005(1):31‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sturgeon P, Itano HA, Bergren WR. Genetic and biochemical studies of ‘intermediate’ types of Cooley's anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1955;1(3):264‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olivieri N, Weatherall D. Clinical aspects of beta thalassemia In: Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs DR, Nagel RL, eds. Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology And Clinical Management. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001;277‐341. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rund D, Rachmilewitz E. β‐Thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1135‐1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taher AT, Musallam KM, Cappellini MD. Thalassaemia intermedia: an update. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2009;1(1):e2009004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thein SL. Genetic modifiers of the β‐haemoglobinopathies. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(3):357‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Propper RD, Button LN, Nathan DG. New approaches to the transfusion management of thalassemia. Blood. 1980;55(1):55‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ansari SH, Shamsi TS, Khan MT, et al. Seropositivity of Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B and HIV in chronically transfused ββ‐thalassaemia major patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2012;22(9):610‐611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bihl F, Castelli D, Marincola F, Dodd RY, Brander C. Transfusion‐transmitted infections. J Transl Med. 2007;5(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaddah N, Salama K, Kaddah AM, Attia R. Epidemiological study among thalassemia intermedia pediatric patients. Med J Cairo Univ. 2010;78(2):651‐655. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taher A, Cappellini MD, Ismaeel H. Thalassemia: the facts and the controversies. Pediatr Nurs. 2006;29(6):447‐451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qatanani M, Taher A, Koussa S, et al. β‐Thalassaemiaintermedia in Lebanon. Eur J Haematol. 2000;64(4):237‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taher A, Isma'eel H, Cappellini MD. Thalassemia intermedia: revisited. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2006;37(1):12‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taher A, Vichinsky E, Musallam KM. Guidelines for the Management of Non Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (NTDT). TIF Publication No. 19. Nicosia, Cyprus, Thalassaemia International Federation, 2013. [PubMed]

- 21. Taher AT, Radwan A, Viprakasit V. When to consider transfusion therapy for patients with non‐transfusion‐dependent thalassaemia. Vox Sang. 2015;108(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karimi M, Yarmohammadi H, Farjadian S, et al. β‐Thalassemia intermedia from southern Iran: IVS‐II‐1 (G→ A) is the prevalent thalassemia intermedia allele. Hemoglobin. 2002;26(2):147‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Camaschella C, Mazza U, Roetto A, et al. Genetic interactions in thalassemia intermedia: analysis of β‐Mutations, α‐Genotype, γ‐Promoters, and β‐LCR hypersensitive sites 2 and 4 in Italian patients. Am J Hematol. 1995;48(2):82‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan J, Ahmad N, Siraj S, Hoti N. Genetic determinants of β‐thalassemia Intermedia in Pakistan. Hemoglobin. 2015;39(2):95‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khan SN, Riazuddin S. Molecular characterization of β‐thalassemia in Pakistan. Hemoglobin. 1998;22(4):333‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Musallam KM, Taher AT, Rachmilewitz EA. β‐thalassemia intermedia: a clinical perspective. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(7):a013482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]