Abstract

Objective

This study was to investigate the changes of antifungal susceptibilities caused by the phenotypic switching in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC).

Methods

229 women were enrolled in this study. The vaginal smears of these patients were collected and gram stained for fungal microscopic observation. The vaginal discharge of them in cotton swabs was cultured in sabouraud's agar with chloramphenicol medium. After fungal culture, fungal identification was analyzed using CHROM agar Candida chromogenic and identification medium. Then, the in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing was carried out using the standardized CLSI M27‐A2 broth microdilution method.

Results

64.63% of Candia species in patients with VVC were Candida albicans and the remainders were non‐albicans Candida species. The phenotypic switching was observed in 91.22% of C. albicans infection. In antifungal susceptibility testing, the susceptible rates of C. albicans to voriconazole, fluconazole and itraconazole were significantly higher than that of non‐albicans Candida species (P = 0.00, 0.00, 0.00). No matters in patients infected with C. albicans or with non‐albicans Candida species, the susceptible rate to fluconazole of the clinical isolates with phenotypic switching was significantly higher than that without phenotypic switching (P = 0.01, 0.01).

Conclusions

In the study, C. albicans was the commonest pathogenic species in patients with VVC, in which the phenotypic switching was easy to occur. The susceptible rates of C. albicans to all antifungal drugs were higher than that of non‐albicans Candida species. The susceptible rate to fluconazole was all influenced by the phenotypic switching in C. albicans and non‐albicans Candida species.

Keywords: antifungal susceptibility testing, Candida albicans, non‐albicans Candida, phenotypic switching, susceptible rate

Abbreviation

- AFST

Antifungal susceptibility testing

- CAP

College of American Pathologists

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- ECVs

epidemiological cutoff values

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- NCCLS

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards

- NSEQA

National System for External Quality Assessment

- PCR‐RFLP

polymerase chain reaction‐restriction fragment length polymorphism

- RVVC

recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis

- VVC

vulvovaginal candidiasis

1. INTRODUCTION

Vulvovaginal candidacies (VVC) is a common vaginal infection disease which is associated with significant morbidity and unacceptable high recurrence rate.1 Candida species is a well‐known opportunistic pathogen of VVC, which includes Candida albicans and non‐albicans Candida species. C. albicans is the commonest opportunistic pathogen in vagina, followed by Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis, and so on.2 However, the etiology of high VVC recurrence is non‐albicans Candida species and the prevalence of other Candida species including C. glabrata is increasing in recent years.3 Moreover, up to 6% women will suffer from recurrent VVC (RVVC),4 which consists in acute and symptomatic individuals.5

Candida species is generally in yeast phase under the normal circumstances. In some cases, phenotypic switching will occur in C. albicans, which is from yeast phase to hypha phase.6, 7, 8 The phenotypic switching may lead to antigenic changes on the cell membrane, local immune response in mucosa, and the occurrence of vaginal inflammation and susceptibility to different antifungal drugs.9 This study was designed to investigate the changes of antifungal susceptibility testing caused by the phenotypic switching in patients with VVC, which was benefit for rational use of antifungal drugs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Samples collection

In this study, 229 patients were enrolled from the obstetrics and gynecology department of West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University from January 2016 to November 2017. The basic information of participants is recorded including their age, pregnancy status, marital status, clinical symptoms, color, and amount of vaginal secretion, itching or dysuria of vulvar, past illness and treatment history before undergoing gynecologic examination. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) Women who suffered from vulva and vaginal itching. (b) The result of fungal culture and morphological examination was positive. (c) Presence or absence of abundant/cheesy vaginal discharge. Women of menstruation, mental disorder (could not answer the questions), those who taking medicines including antifungal drugs and/or topical vaginal creams within 7 days before examination and those who was diagnosed with RVVC (Who were diagnosed with VVC and their clinical symptoms and signs disappeared after treatment, then relapsed four or more times a year after negative mycological examination) were specifically excluded from the study. Vaginal discharge of these patients was collected by sterile cotton swabs (Medical Apparatus and Instruments Factory of Yangzhou Chuangxin, Jiangsu, China). A part of vaginal discharge on sterile cotton swabs was made into smears for fungal morphologic observation, the rest were used for fungal culture, identification, and antifungal susceptibility testing. In our study, the written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the privacy rights of participants were also reserved. And all procedures and protocols are in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University before study initiation.

2.2. Gram staining and microscopic observation

Vaginal smears of these 229 patients were subjected to gram staining. The exact staining procedure may refer to related literature by Dai et al10 After gram staining, the presence or absence of gram positive yeasts with/or without budding and/or pseudohyphae in vaginal smears were observed under microscope. It is reported that the formation of hyphae or pseudohyphae is the symbol of fungal phenotypic switching.11 Candida species were identified by two laboratory microbiologists under the oil immersion field microscope based on the National System for External Quality Assessment (NSEQA) and the College of American Pathologists (CAP).12

2.3. Fungal culture

The vaginal discharge in cotton wool‐tipped swabs was cultured in sabouraud's agar with chloramphenicol medium (Jinzhang science and technology development limited company, Tianjin). After incubation at 37°C for 2‐3 days, the gray‐white cheese colonies formed. Ovoid yeasts and pseudohyphae were also observed after gram staining. The colony would be regarded as C. albicans or non‐albicans Candida species.

2.4. Fungal identification and in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing

After fungal culture, fungal identification was analyzed using CHROM agar Candida chromogenic and identification medium (CHROM agar Company, France). Only one isolate had been identified from per patient. So, there were 229 clinical isolates were initially identified in this study. When the results of fungal culture were positive and the isolates were identified as C. albicans or one of non‐albicans Candida species, the susceptibilities of Candida species to azole antifungal drugs (fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole) and 5‐Flucytosine were determined using the standardized CLSI M27‐A2 broth microdilution method with the following testing guidelines: (a) RPMI 1640 with 2% dextrose medium to enhance the growth of yeast cells; (b) an inoculum size of 0.5 × 105 to 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL; (c) flat‐bottom microdilution trays; and (d) 24‐hour spectrophotometric MICs.13 Important new developments including validation of 24‐hour reading times for all antifungal agents and the species‐specific epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) were established Conversely, ECVs can be considered to represent the most sensitive measure of the emergence of strains with decreased susceptibility to a given agent.14 The interpretive breakpoints for susceptibility to azoles were those employed by Sanguinetti et al15 and were as follows: (a) fluconazole, ≤8 mg/L, sensitive; ≥64 mg/L, resistant; (b) voriconazole, ≤1 mg/L, sensitive; ≥4 mg/L, resistant; (c) itraconazole, ≤0.125 mg/L, sensitive; ≥1 mg/L, resistant; (d) 5‐ Flucytosine, ≤4 mg/L, sensitive; ≥32 mg/L, resistant. The susceptibilities of isolates to amphotericin B were assayed as described previously.16 The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for amphotericin B was defined as the lowest drug concentration at which growth was completely inhibited.17

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed by SPSS Statistics ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The comparison of different prevalence among Candida species and the different positive rates of phenotypic switching were analyzed by Chi‐squared test. A 2‐tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and a 2‐tailed P < 0.01 was considered extremely statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Results of microscopic observation and fungal identification

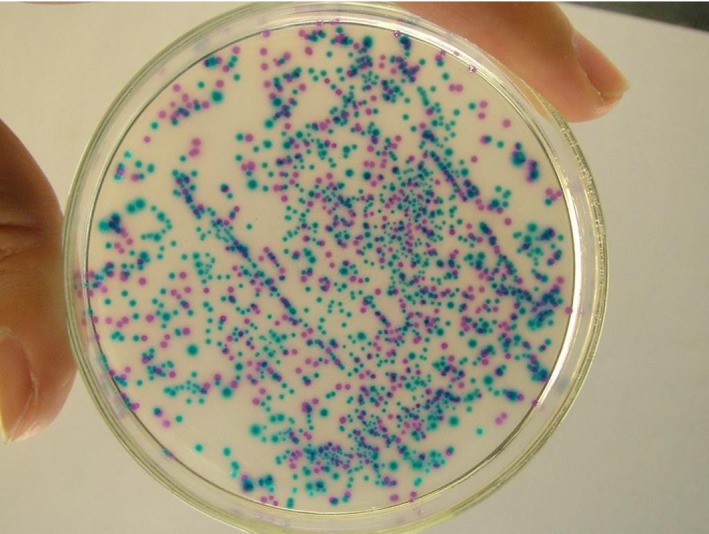

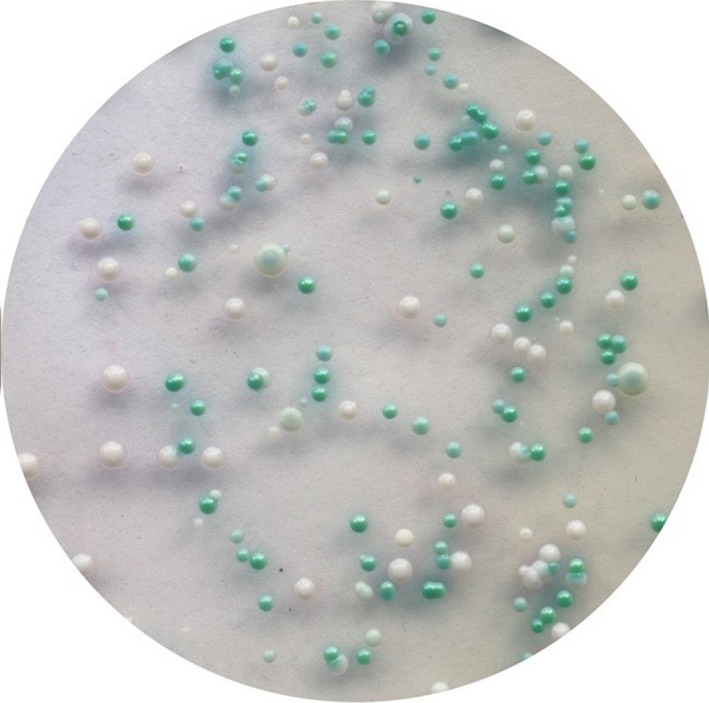

In CHROM agar Candida chromogenic and identification mediums, the colonies were shown in Figures 1 and 2. The colony color of C. albicans was green (diameter: 2 mm), while the colony color of C. glabrata was purple (diameter: 2 mm). The colony color of C. krusei and C. tropicalis was soft pink (diameter: 4‐5 mm) and blue gray or iron blue (diameter: 1.5 mm) respectively. The colony color of C. parapsilosis was white.

Figure 1.

The colors of Candida species in CHROMagar Candida chromogenic and identification medium. The color of green and purple represents C. albicans and C. glabrata, respectively; the color of soft pink and blue‐gray represents C. krusei and C. tropicalis, respectively

Figure 2.

The colors of two Candida species in CHROMagar Candida chromogenic and identification medium. The color of iron blue and white represents the C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis, respectively

According to the colony morphology, 64.63% of Candia species in patients with VVC were identified as C. Albicans(n = 148) and the remainders (n = 81, 35.37%) were identified as non‐albicans Candida species (showed in Table 1). In the clinical isolates identified as non‐albicans Candida species, 91.36%, 2.47%, 2.47%, 2.47%, and 1.23% of them were identified as C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae respectively. Although we have not used the molecular method to identify the Candida species, instead of using CHROM agar Candida chromogenic and identification medium, the results of our study were consistent with the results of Hasanvand et al18 and Seyed Amir Y et al.19

Table 1.

Antifungal susceptibility testing of different Candida species and the difference of drug‐susceptible rates between Candia isolates with and without phenotypic switching

| Positive rates (Cases/total cases) | The percentage of drug‐susceptible cases and the susceptible difference between isolates with and without phenotypic switching | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B (%, χ 2, P) | 5‐Fluorocytosine (%, χ 2, P) | Voriconazole (%, χ 2, P) | Fluconazole (%, χ 2, P) | Itraconazole (%, χ 2, P) | |||||||

| Candida albicans | 64.63 (148/229) | 148 (100%) | 148 (100%) | 132(89.20%) | 121(81.76%) | 111(75.00%) | |||||

| With phenotypic switching | 91.22% (135/148) | 135 (100%) | 0, >0.99a | 135 (100%) | 0, >0.99a | 123 (91.11%) | 1.26, 0.26a | 114 (84.44) | 7.44, 0.01a | 98 (72.59%) | 0.07, 0.80a |

| Without phenotypic switching | 8.78% (13/148) | 13 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 7 (58.35%) | 9 (69.23%) | |||||

| Non‐albicans candida (NAC) | 35.37% (81/229) | 80 (98.77%) | 0.09, 0.76b | 79 (97.53%) | 1.39, 0.24b | 58 (71.60%) | 11.46, 0.00b | 47 (58.02%) | 15.09, 0.00b | 20 (24.69%) | 54.12, 0.00b |

| With phenotypic switching | 19.75% (16/81) | 16 (100%) | 0.25, 0.62a | 15 (93.75%) | 0.04, 0.85a | 12 (75.00%) | 0.11, 0.74a | 9 (56.25%) | 6.02, 0.01a | 5 (31.25) | 0.46, 0.50a |

| Without phenotypic switching | 80.25% (65/81) | 64 (98.46%) | 64 (98.46%) | 46 (70.77%) | 16 (24.62%) | 15 (23.08%) | |||||

The difference of drug‐susceptible rates between Candida isolates with phenotypic switching and Candida isolates without phenotypic switching

The difference of drug‐susceptible rates between C. albicans isolates and non‐albicans candida isolates.

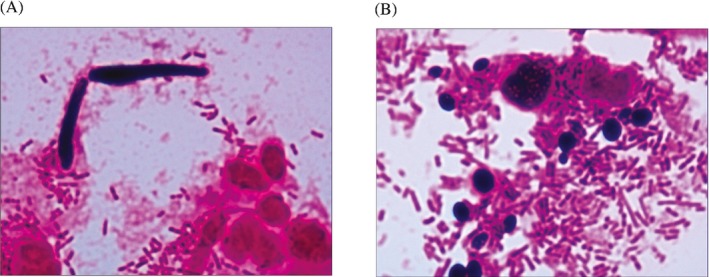

Based on related literature by Ilkit et al,11 after gram staining, the finding of pseudohyphae was regarded as phenotypic switching (Figure 3A). And the finding of yeasts without budding (without pseudohyphae) was regarded as non‐phenotypic switching (Figure 3B). The yeasts with budding and pseudohyphae were observed in 91.22% of clinical isolates identified as C. albicans, which indicated that 91.22% of these clinical isolates were with phenotypic switching. The remainder (8.78%) was without phenotypic switching. Meanwhile, the pseudohypha was not observed in 80.25% of clinical isolates identified as non‐albicans Candida species, which indicated that 80.25% of these clinical isolates was without phenotypic switching, the remainders (19.75%) was with phenotypic switching (showed in Table 1).

Figure 3.

A, the presence of pseudohyphae under microscopic observation (with phenotypic switching) (Gram staining, 1000×); B, the presence of yeasts without budding under microscopic observation (without phenotypic switching) (Gram staining, 1000×)

3.2. Results of in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing

In antifungal susceptibility testing in vitro, the susceptible rates to amphotericin B, 5‐fluorocytosine, voriconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole of C. Albicans isolates with and without phenotypic switching were listed in Table 1. The susceptible rates to the above five drugs of non‐albicans Candida isolates with & without phenotypic switching and the difference of the susceptible rate between C. Albicans isolates and non‐albicans Candida isolates were also listed. The susceptible rates of C albicans isolates to voriconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole were higher than that of non‐albicans Candida isolates (P = 0.00,0.00,0.00). No matters for C. Albicans isolates and non‐albicans Candida isolates, the susceptible rate to fluconazole with phenotypic switching was significantly higher than that without phenotypic switching (P = 0.01,0.01).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, through fungal morphology observation and fungal identification, C. albicans was found to be the main pathogen of VVC. This is consistent with the findings in previous studies.20, 21, 22 C. glabrata was the commonest pathogenic species in non‐albicans Candida species, followed by C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which was supported by other reports.2, 23 Furthermore, VVC caused by Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been firstly reported in China or other countries.20

The yeasts with budding and pseudohyphae were observed in 91.22% of C. albicans isolates, in which the fungal phenotypic switching had occurred. Meanwhile, the pseudohyphae was not observed in 80.25% of non‐albicans Candida isolates, in which the phenotypic switching did not happen. This indicated that the infection of C. albicans was more prone to fungal phenotypic switching than that of non‐albicans Candida species.24 Meanwhile, it was the first time to find that yeasts with budding and pseudohyphae were observed in 19.75% of clinical isolates identified as non‐albicans Candida, which indicated that 19.75% of these clinical isolates was with phenotypic switching.

On account of the immunological mechanisms, fungal phenotypic switching can cause the changes of Candida antigens. The phenotypic switching of Candida species from yeast phase to hypha phase may cause the topical mucosal immunological responses and strengthen the invasiveness capacity of toxicity to host. The hyphal formation of Candida species is the main symbol of phenotypic switching.11, 21 The hyphae can grow along the fissure of skin and mucosa by mechanical force and finally pass through the skin or skin epithelial cells, which are two important steps of fungal infection.25

In antifungal susceptibility testing, the susceptible rates of C. albicans to all antifungal drugs were higher than non‐albicans Candida species (Tab. 1). The susceptible rates of C. albicans to voriconazole, fluconazole and itraconazole were significantly higher than that of non‐albicans Candida species, which indicated that the commonly used antifungal drugs aimed to VVC caused by C. albicans were more effective than that caused by non‐albicans Candida species. Patients infected with non‐albicans Candida species have various degrees of resistance to different antifungal drugs.11 Azole antifungals are efficient in clearing the acute infection but unable to prevent the recurrence of VVC. So, it should be careful when using these two kinds of drugs.26

Fungal phenotypic switching was associated with the susceptibility of some antifungal drugs. In immune activation state, fungal hyphae are more easily inhibited or destructed by azole antifungals such as fluconazole.27 Therefore, azole antifungals have better therapeutic effect against VVC caused by C. albicans. Non‐albicans Candida species is often in the form of yeasts without budding and phenotypic switching occurred rarely on their fungal cell membrane. The antigenicity does not change and is immunology suppressed. Yeasts has far lower toxicity and invasion to the body than fungal hyphae do. The conventional antifungal drugs such as fluconazole did not inhibit or damage the yeasts. So, the susceptible rates of non‐albicans Candida species to these antifungal drugs are decreased. Meanwhile, the drug resistance spectrum increased, which is further increased with the overuse of antifungal drugs.28

In this study, the susceptible rate to fluconazole of C. Albicans isolates with phenotypic switching was significantly higher than that without phenotypic switching. It was mainly because that fungal phenotypic switching can cause the change of Candida antigens, leading to the rise of susceptibility to azole antifungal such as fluconazole. Meanwhile, the susceptible rate to fluconazole of non‐albicans Candida species with phenotypic switching was still significantly higher than that without phenotypic switching. However, whether phenotypic switching occurred or not, there was no significant difference of the susceptible rates to other drugs such as amphotericin B, 5‐fluorocytosine, itraconazole, and voriconazole in Candida isolates.

In summary, C. albicans was the commonest pathogenic species of VVC, which was easy to convert from yeast phase to hypha phase. Meanwhile, the phenotypic switching was rarely occurred in non‐albicans Candida species. The susceptible rate of C. albicans to antifungal drugs was higher than that of non‐albicans Candida species. No matters for patients infected with C. albicans or with non‐albicans Candida species, the susceptible rates to fluconazole with phenotypic switching was significantly higher than that without phenotypic switching. So, the rational use of fluconazole would be based on the fungal phenotypic switching in patients with VVC.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sorts of antifungal drugs for susceptibility testing were quite less, which could not completely represent all antifungal drugs. Therefore, newer antifungal drugs will be used in our future studies. Second, in patients who infected with non‐albicans Candida species, regardless of cases with or without phenotypic switching, the study number was relatively small, which may lead to statistical error to an extent. More cases will be enrolled in our future study. Third, although the antifungal susceptibilities of different non‐albicans Candida species such as C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis are different, however, because of the small number and proportion of C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae cases, the susceptibilities of all non‐albicans Candida isolates had to be counted together in our study. Furthermore, molecular method such as PCR‐RFLP analysis would be used to identify the Candida species instead of using CHROM agar Candida chromogenic and identification mediums.17, 18

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We feel grateful to the staffs of the Department of Laboratory Medicine and the doctors of the outpatient department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, China. We also appreciate the investigators of Key Laboratory of the Ministry of Education for Maternal and Child Diseases and Birth Defects (Sichuan University).

Tang Y, Yu F, Huang L, Hu Z. The changes of antifungal susceptibilities caused by the phenotypic switching of Candida species in 229 patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22644 10.1002/jcla.22644

Yuanting Tang and Fan Yu contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amouri I, Sellami H, Borji N, et al. Epidemiological survey of vulvovaginal candidosis in Sfax, Tunisia. Mycoses 2011;54:e499Y505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Leon EM, Jacober S, Sobel JD, Foxmanet B. Prevalence and risk factors for vaginal Candida colonization in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. BMC Infect Dis. 2002;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonfim‐Mendonca PDE, Ratti BA, Godoy Jda S, et al. β‐Glucan induces reactive oxygen species production in human neutrophils to improve the killing of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata isolates from vulvovaginal candidiasis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. Lancet. 2007;369:1961‐1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fidel PL Jr. History and update on host defense against vaginal candidiasis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;57:2‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang G. Regulation of phenotypic transitions in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Virulence. 2012;3:251‐261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cassone A. Vulvovaginal Candida albicans infections: pathogenesis, immunity and vaccine prospects. BJOG‐Int J Obstet Gyn. 2015;122:785‐794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yue H, Hu J, Guan G, et al. Discovery of the gray phenotype and white‐gray‐opaque tristable phenotypic transitions in Candida dubliniensis. Virulence. 2016;7(3):230‐242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Milanese M, Segat L, De Seta F, et al. MBL2 genetic screening in patients with recurrent vaginal infections. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:146‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dai Q, Hu L, Jiang Y, et al. An epidemiological survey of bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis and trichomoniasis in the Tibetan area of Sichuan Province, China. Eur J Obstet Gyn R B. 2010;150:207‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ilkit M, Guzel AB. The epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidosis: a mycological perspective. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:250‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu Z, Zhou W, Mu L, Kuang L, Su M, Jiang Y. Identification of cytolytic vaginosis versus vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2015;19:152‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards . Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27‐A2. NCCLS, 2002; Wayne PA.

- 14. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Progress in antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida spp. by use of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods, 2010 to 2012. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(9):2846‐2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Fiori B, Ranno S, Torelli R, Fadda G. Mechanisms of azole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata collected during a hospital survey of antifungal resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:668‐679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelly SL, Lamb DC, Kelly DE, et al. Resistance to fluconazole and crossresistance to amphotericin B in Candida albicans from AIDS patients caused by defective sterol Delta (5,6)‐desaturation. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:80‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park BJ, Arthington‐Skaqqs BA, Hajjeh RA, et al. Evaluation of amphotericin B interpretive breakpoints for Candida bloodstream isolates by correlation with therapeutic outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1287‐1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hasanvand S, Azadegan Qomi H, Kord M, Didehdar M. Molecular epidemiology and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of candida isolates from women with vulvovaginal candidiasis in Northern Cities of Khuzestan Province, Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2017;10(8):e12804. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seyed Amir Y, Sadegh K, Hamed F, et al. Molecular characterization of highly susceptible Candida africana from vulvovaginal candidiasis. Mycopathologia. 2015;180(5–6):317‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jamilian M. Frequancy of vulvovaginal Candidiasis species in nonpregnant 15‐50 years old women in spring 2005 in Arak. P Soc Exp Bio Med. 2007;69:198. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ekpenyong CE, Inyang‐etoh EC, Ettebong EO, Akpan UP, Ibu JO, Daniel NE. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis among young women in south eastern Nigeria: the role of lifestyle and health‐care practices. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23:704‐709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amouri I, Hadrich I, Abbes S, Sellami H, Ayadi A. Local humoral immunity in vulvovaginal candidiasis. Ann Biol Clin‐Paris. 2013;71:151‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rezai MS, Vaezi A, Fakhim H, et al. Successful treatment with caspofungin of candiduria in a child with Wilms tumor; review of lite rapture. J Mycol Med. 2017;27(2):261‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Veses V, Gow NA. Pseudohypha budding patterns of Candida albicans. Med Mycol. 2009;47(3):268‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Markovich S, Yekutiel A, Shalit I, et al. Genomic approach to identification of mutations affecting caspofungin susceptibility in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3871‐3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raska M, Belakova J, Krupka M, Weigl E. Candidiasis–do we need to fight or to tolerate the Candida fungus? Folia Microbiol. 2007;52:297‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, Penny Danna P, Teng‐Chiao C. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:876‐883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosa MI, Silva BR, Pires PS, et al. Weekly fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;167:132‐136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]