Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the significance of change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) during preoperative chemoradiotherapy (preop-CRT) in patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer using a propensity score matching method (PSM).

Methods

Patients who underwent surgery after completion of preop-CRT for non-metastatic rectal cancers from Jan 2004 to Dec 2013 were retrospectively enrolled. NLRs were obtained before commencement of CRT (pre-NLR) and between completion of CRT and surgery (post-NLR). Using Cox regression hazards models, the association of NLRs with survival after PSM was examined.

Results

A total of 131 patients were grouped as follows: group A, pre-NLR < 3 & post-NLR < 3 (n = 47); group B, pre-NLR < 3 & post-NLR ≥ 3 (n = 45); group C, pre-NLR ≥ 3 & post-NLR < 3 (n = 5); group D, pre-NLR ≥ 3 & post-NLR ≥ 3 (n = 34). There was no difference in disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS) rate according to group. When dichotomized into group A versus groups B-D, DFS was higher in group A (84.7%) than groups B-D (67.5%, p = 0.021). After PSM (n = 94), multivariable analysis identified persistent lower NLR as an independent favorable prognosticator of DFS (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.92, p = 0.033).

Conclusions

Persistent non-inflammatory state measured by NLR may be an indicator of decreased risk of recurrence in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preop-CRT.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a major cause of cancer-related death worldwide and in South Korea.[1–3] Among them, nearly 30% of patients had been diagnosed with rectal cancer.[2] According to guidelines, standard care for locally advanced rectal cancer (clinical stage II and III) is preoperative chemoradiotherapy (preop-CRT) followed by total mesorectal excision.[4,5] Although preop-CRT may decrease local recurrence rate in comparison to postoperative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, it does not improve overall survival (OS).[4,5] Risk stratification for high risk patients to designate proper management is important to improve prognostic outcomes in these patients.

Various markers reflecting systemic inflammatory response, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and the modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS), are demonstrated prognostic factors for survival in primary operable cancers.[6] Although albumin or CRP are not usually assessed as part of the preoperative workup for cancer patients, differential white cell count is routinely performed to identify patients with hypercoagulability or infection risk.[6] Among these laboratory markers, NLR is one of the most commonly used biomarkers. It was reported that tumor affected the hematopoietic progenitor cell of the host and thus myeloid lineage populations (including neutrophils) could expand.[7] These myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) suppress host immune cells through various pathways and could diminish lymphocytes.[8] NLR could be used to estimate the relative balance of myeloid and lymphocytic lineages, thus reflecting host immunity in cancer patients.[8] The prognostic impact of NLR was thoroughly investigated in different types of diseases including gastric cancer, hepatocellular cancer, pancreatic cancer, head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, and thyroid cancer.[9–15] In accordance with these results, previous studies including a meta-analysis demonstrated that NLR can predict survival outcome,[16–22] or can also predict tumor regression grade, such as pathologic complete response (pCR), or good tumor response after preop-CRT in patients with rectal cancer.[18,20,23–25]

Nevertheless, there are also a number of studies that have shown that NLR is not relevant in patients with rectal cancer. Lino-Silva and colleagues reported that there were no differences in survival outcomes or pCR rate according to NLR cut-off point (2.0, 2.5, 4, and 5) in 175 patients who underwent preop-CRT.[26] Shen and colleagues also reported that NLR measured in pre-CRT did not predict OS or disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent preop-CRT.[27] Jung et al. reported that NLR measured before commencement of preop-CRT could not discriminate recurrence-free survival (p = 0.07) among 984 patients who underwent preop-CRT.[28] Portale and coworker recently demonstrated that neither PLR nor NLR were associated with survival and recurrence in patients undergoing laparoscopic curative resection for rectal cancer with or without preop-CRT.[29] The basis of this discrepancy among studies is not clearly understood.

The long course of preop-CRT for locally advanced rectal cancer patients usually takes 11–15 weeks from preop-CRT commencement to the date of definite surgery. As has been recently suggested, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts are not constant over time during preop-CRT for rectal cancer.[30] So, the NLR will vary in value. Most previous studies evaluating the impact of NLR on survival or tumor response for rectal cancer measured NLR at a specific time, mainly before initiating preop-CRT, or used the NLR value assessed before preop-CRT.[16–20,23–29,31] In contrast, the prognostic significance of change in NLR during preop-CRT for rectal cancer has not been widely assessed.[32]

Our study aimed to investigate the impact of changes in pre- and post-chemoradiotherapy neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios (NLRs) on the prognosis of patients with rectal cancer who underwent preop-CRT.

Materials and methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using consecutive patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer who underwent preop-CRT followed by surgery from Jan 2004 to Dec 2013. All patients diagnosed with clinical stage II or III rectal cancer who underwent long-course preop-CRT were screened. Patients who underwent emergent or palliative surgeries, were diagnosed as stage IV at initial staging workup, with history of inflammatory bowel disease, or with any missing blood examination data during preop-CRT were excluded from this study. Finally, 131 patients were included in this analysis.

Routine demographic variables, surgical outcomes, and oncologic outcomes were obtained from the electronic medical records, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet counts, type of surgery, hospital stay, recurrence, and survival. NLR was defined by dividing absolute neutrophil count by absolute lymphocyte count and was calculated twice for each patient using the complete blood count (CBC) performed before CRT (pre-NLR) and between completion of CRT and surgery (post-NLR). Additional blood test between these two examinations was not routinely performed. This study was approved by Gangnam Severance Hospital’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived for this retrospective study.

Preoperative chemoradiotherapy, total mesorectal excision and follow up

All patients underwent conventional radiotherapy (RT) with concurrent 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Mean 50.4 Gy radiation dose was irradiated in 28 fractions over 5 weeks. RT was applied to the whole pelvis with 45 Gy in 25 fractions, with a boost of 5.4 Gy to the primary tumor in 3 fractions. Patients were treated with 3 portals of posterior and bilateral beams in the prone position. The superior border was 1.5 cm above the sacral promontory (L5 level), and the inferior border was at the inferior margin of the obturator foramen or 3 cm below the lower tumor margin. The lateral border was 1.5 cm lateral to the bony pelvis, and the anterior border was 3 cm anterior to the tumor. The posterior border was 0.5 cm posterior to the sacral surface. The boost volume was 3 cm expansion from the primary tumor in the superior and inferior directions and 2 cm expansion radially. Chemotherapy regimens were either intravenous 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or oral capecitabine. Intravenous chemotherapy was administered at a dose of 425 mg/m2/day of 5-FU with 20 mg/m2/day of leucovorin during the first and fifth weeks of radiation treatment (RT). Oral capecitabine was administered at a dose of 1,650 mg/m2/day during the whole RT period. Surgery was performed in accordance with the principle of total mesorectal excision (TME) at 6 to 12 weeks after completion of preop-CRT. After surgery, patients were followed up in an out-patient clinic every 3 months for the first 3 years and 3–6 months thereafter until 5 years from the initial surgery. CEA was assessed at each visit. Chest and abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) was performed every 6 or 12 months according to postoperative stage. Colonoscopy was recommended at 1, 3, and 5 years after surgery. Positron-emission tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging was added according to physician discretion. Local and distant metastases were defined according to clinical and radiologic evaluations. Biopsy confirmation was not always mandatory to confirm recurrence.

Classifications according to NLRs measured at two different time points during preoperative chemoradiotherapy

To assess the significance of the change in NLRs while receiving preop-CRT, patients were stratified into 4 groups using the cut-off value of 3 for both pre-NLR and post-NLR. This cut-off value was derived from previous studies on the impact of NLR for patients with colorectal cancer.[33–35] In brief, patients were grouped as follows: group A, pre-NLR < 3 & post-NLR < 3; group B, pre-NLR < 3 & post-NLR ≥ 3; group C, pre-NLR ≥ 3 & post-NLR < 3; group D, pre-NLR ≥ 3 & post-NLR ≥ 3. Patients were further sub-stratified as group A versus groups B-D based on survival outcomes in further analysis.

Propensity score matching

After sub-stratifying the entire cohort into group A versus groups B-D, significant difference in clinical T stage and marginal difference in clinical N stage was identified between the two groups, which might affect long-term oncologic outcomes. The following covariates were included in the model to calculate the propensity score: clinical T stage and clinical N stage. The NLR dichotomization (group A vs. control) was entered into the regression model as the dependent variable. Matching of propensity scores was obtained with the 1:1 optimal matching method.

Further analysis of the impact of neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLR and LMR on DFS and OS

Using the cohort after propensity score matching, we further evaluated the significance of neutrophil, lymphocyte, PLR and LMR with DFS and OS. PLR was defined as the absolute platelet count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count. LMR was defined as the absolute lymphocyte count divided by the absolute monocyte count. First, patients were stratified into the 2 groups using the cut-off value of median for neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLR and LMR respectively. Second, patients were separately into four grouped as follows: pre- < median & post- < median; pre- < median & post- ≥ median; pre- ≥ median & post- < median; pre- ≥ median & post- ≥ median. Finally, patients were sub-stratified as pre- < median & post- < median vs. control in further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Differences in clinicopathologic features between groups were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and with Student’s t-test for continuous variables. The primary clinical outcomes of interest were OS and DFS. OS duration was defined as the time from the date of operation to the date of death or last follow-up. DFS duration was defined as time from the date of operation to the date of recurrence (local recurrence or/and distant metastasis), death, or last follow-up. Local recurrence-free survival (LRFS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were defined as time from the date of surgery to the occurrence of locoregional recurrence or distant metastasis, respectively. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for survival analysis, and the log-rank test was used to compare survival outcomes between the groups. Univariable and multivariable analyses were performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Variables that had significance of p ≤ 0.1 on univariable analysis were eligible for inclusion in multivariable analysis. Multivariable models were derived using forward stepwise selection. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.5.1 (R-project, Institute for Statistics and Mathematics).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 131 patients were included in this study. The median follow-up period was 73.3 [interquartile range (IQR) 56.2–98.1)] months. The majority of patients was male (65.6%) and diagnosed with low rectal tumor (tumor was located below 6 cm from the anal verge) (71.8%). The median age was 59 (IQR, 51–67) years, and median BMI was 23.3 (IQR, 21.4–24.8) kg/m2. Median CEA before starting preop-CRT was 4 (IQR, 2–8) ng/mL. In pre-treatment staging before preop-CRT, there were 19 (14.5%), 67 (51.1%), and 45 (34.4%) cT2, cT3, and cT4, respectively. Most patients (80.2%) were diagnosed as clinically node positive.

The median values of pre-NLR and post-NLR were 2.25 (IQR, 1.64–3.29) and 3.46 (IQR, 2.57–4.75), respectively (p < 0.01). Median days from measurement of pre-NLR and post-NLR to the date of surgery were 98 (IQR, 84–109) and 13 (IQR, 7–18) days, respectively. The proportion of patients with greater than 3 NLR was 29.8% in pre-NLR and 60.3% in post-NLR (p < 0.001). Combining the cut-off value of 3 in pre- and post-NLRs, 47 (35.9%), 45 (34.4%), 5 (3.8%), and 34 (26%) patients were classified into group A, group B, group C, and group D, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinicopathologic characteristics of overall patients (n = 131).

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 86 (65.6) |

| Female | 45 (34.4) | |

| Age (years) | median (IQRa) | 59 (51–67) |

| BMIb (kg/m2) | median (IQR) | 23.3 (21.4–24.8) |

| Tumor distance from anal verge (cm) | < 6 | 94 (71.8) |

| ≥ 6 | 37 (28.2) | |

| Pre-CRT CEAc (ng/mL) | median (IQR) | 4 (2–8) |

| cT stage | cT2 | 19 (14.5) |

| cT3 | 67 (51.1) | |

| cT4 | 45 (34.4) | |

| cN stage | cN (–) | 26 (19.8) |

| cN (+) | 105 (80.2) | |

| pre-NLR | median (IQR) | 2.25 (1.64–3.29) |

| < 3 | 92 (70.2) | |

| ≥ 3 | 39 (29.8) | |

| post-NLR | median (IQR) | 3.46 (2.57–4.75) |

| < 3 | 52 (39.7) | |

| ≥ 3 | 79 (60.3) | |

| Combination of pre&post NLRs | pre-NLR<3 & post-NLR<3 (Group A) | 47 (35.9) |

| pre-NLR<3 & post-NLR≥3 (Group B) | 45 (34.4) | |

| pre-NLR≥3 & post-NLR<3 (Group C) | 5 (3.8) | |

| pre-NLR≥3 & post-NLR≥3 (Group D) | 34 (26) |

aIQR: interquartile range

bBMI: body mass index

cCEA: carcinoembryonic antigen

Overall survival, disease-free survival, local recurrence-free survival, and distant metastasis-free survival among 131 patients

Of the 131 patients, local recurrence was observed in 6 (4.5%) and distant metastasis occurred in 30 (22.9%) during the study period. Overall, death occurred in 38 patients (29%). The 5-year OS and DFS rates were 80.1% and 73.6%, respectively, for all patients. The 5-year LRFS and DMFS were 95.3% and 78%, respectively, for all patients.

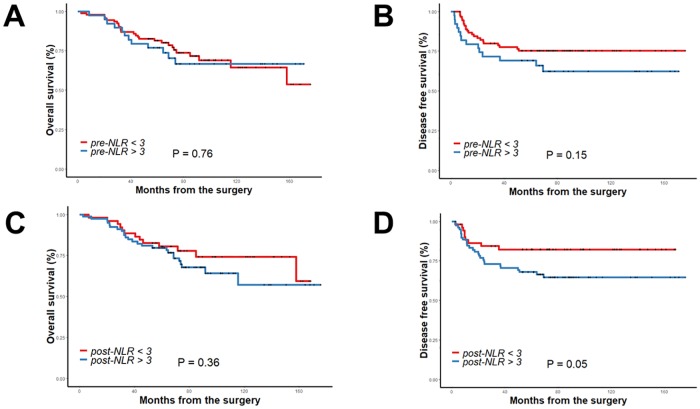

When survival outcomes were compared according to the cut-off value of 3 in pre-NLR, OS and DFS did not differ between the pre-NLR < 3 and pre-NLR ≥ 3 groups (OS: p = 0.76, DFS: p = 0.15). At a cut-off value of 3 for post-NLR, there was no difference of OS (p = 0.36) between the post-NLR < 3 and post-NLR ≥ 3 groups. There was a trend toward better DFS in the post-NLR < 3 group compared with the post-NLR ≥ 3 group (p = 0.05) (Fig 1A–1D).

Fig 1. Overall survival and disease-free survival according to cut-off value 3 of pre-NLR (A, B) and post-NLR (C, D).

Next, OS and DFS were compared among the 4 groups (groups A-D). There was no significant difference in 5-year OS or 5-year DFS among the four groups (OS: 82.7% in group A, 80% in group B, 60% in group C, and 79.4% in group D, p = 0.620, DFS: 84.7% in group A, 65.9% in group B, 60% in group C, and 70.6% in group D, p = 0.125) (Fig 2A and 2B). When patients were further sub-stratified into group A versus groups B-D, there was no significant difference in 5-year OS between the two groups (82.7% in group A vs. 78.6% in groups B-D, p = 0.245). In contrast, the 5-year DFS rate was significantly better in group A than in groups B-D (84.7% in group A vs. 67.5% in groups B-D, p = 0.021) (Fig 2C and 2D).

Fig 2. Overall survival and disease-free survival according to combination of pre and post NLRs using cut-off value 3 (A, B) and according to group A versus groups B-D (C, D) in whole cohort (n = 131).

Propensity score matching

The patient characteristics of group A versus groups B-D are described in Table 2. Among 131 patients (before PSM), a significantly higher proportion in groups B-D had advanced clinical T stage (p = 0.008). Although it was not statistically significant, clinically node positive patients were more predominant in groups B-D compared to group A (84.5% vs. 72.3%, p = 0.112). Because this imbalance of preoperative clinical staging could impact survival outcomes, PSM with the 1:1 matching method was performed using clinical T and N stages. After matching, there was no difference in clinicopathologic variables between the two groups.

Table 2. Patients’ characteristics according to combination of pre and post-chemoradiotherapy neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio before and after propensity score matching (PSM).

| Unmatched patients (n = 131) | Matched patients (n = 94) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 47) n (%) |

Group B-D (n = 84) n (%) |

P | Group A (n = 47) n (%) |

Control (n = 47) n (%) |

P | ||

| Gender | Male | 28 (59.6) | 58 (69) | 0.338 | 28 (59.6) | 33 (70.2) | 0.388 |

| Female | 19 (40.4) | 26 (31) | 19 (40.4) | 14 (29.8) | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 31 (66) | 62 (73.8) | 0.423 | 31 (66) | 35 (74.5) | 0.499 |

| ≥ 65 | 16 (34) | 22 (26.2) | 16 (34) | 12 (25.5) | |||

| BMIa (kg/m2) | < 25 | 34 (72.3) | 68 (81) | 0.278 | 34 (72.3) | 35 (74.5) | 1.0 |

| ≥ 25 | 13 (27.7) | 16 (19) | 13 (27.7) | 12 (25.5) | |||

| Tumor distance from anal verge (cm) | < 6 | 40 (85.1) | 54 (64.3) | 0.015 | 40 (85.1) | 38 (80.9) | 0.785 |

| ≥ 6 | 7 (14.9) | 30 (35.7) | 7 (14.9) | 9 (19.1) | |||

| Pre-CRT CEAb (ng/mL) | < 5 | 33 (70.2) | 48 (57.1) | 0.189 | 33 (70.2) | 28 (59.6) | 0.388 |

| ≥ 5 | 14 (29.8) | 36 (42.9) | 14 (29.8) | 19 (40.4) | |||

| cT stagec | cT2 | 11 (23.4) | 8 (9.5) | 0.008 | 11 (23.4) | 8 (17) | 0.772 |

| cT3 | 27 (57.4) | 40 (47.6) | 27 (57.4) | 30 (63.8) | |||

| cT4 | 9 (19.1) | 36 (42.9) | 9 (19.1) | 9 (19.1) | |||

| cN stagec | cN (–) | 13 (27.7) | 13 (15.5) | 0.112 | 13 (27.7) | 10 (21.3) | 0.632 |

| cN (+) | 34 (72.3) | 71 (84.5) | 34 (72.3) | 37 (78.7) | |||

| Operation method | LARd | 25 (53.2) | 43 (51.2) | 0.890 | 25 (53.2) | 17 (36.2) | 0.241e |

| CAAf /ISRg | 19 (40.4) | 33 (39.3) | 19 (40.4) | 25 (53.2) | |||

| APRh/Hartmann | 3 (6.4) | 8 (9.5) | 3 (6.4) | 5 (10.6) | |||

| Complications | Yes | 16 (34) | 31 (36.9) | 0.850 | 16 (34) | 15 (31.9) | 1.0 |

| No | 31 (66) | 32 (68.1) | 31 (66) | 32 (68.1) | |||

| Anastomotic leakagei | Yes | 1 (2.3) | 4 (5.3) | 0.651 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1.0 |

| No | 43 (97.7) | 72 (94.7) | 43 (97.7) | 42 (100) | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | < 5 | 47 (100) | 71 (93.4) | 0.157e | 47 (100) | 45 (95.7) | 0.495e |

| ≥ 5 | 0 | 5 (6.6) | 0 | 2 (4.3) | |||

| ypT | ypT0-2 | 31 (66) | 35 (41.7) | 0.011 | 31 (66) | 23 (48.9) | 0.144 |

| ypT3-4 | 16 (34) | 49 (58.3) | 16 (34) | 24 (51.1) | |||

| ypN | Negative | 38 (80.9) | 57 (67.9) | 0.153 | 38 (80.9) | 36 (76.6) | 0.802 |

| Positive | 9 (19.1) | 27 (32.1) | 9 (19.1) | 11 (23.4) | |||

| pCRj | Yes | 10 (21.3) | 12 (14.3) | 0.336 | 10 (21.3) | 7 (14.9) | 0.593 |

| No | 37 (78.7) | 72 (85.7) | 37 (78.7) | 40 (85.1) | |||

| CRMk | Positive (≤ 1 mm) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (3.9) | 0.834e | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.3) | 0.164e |

| Negative (> 1 mm) | 17 (36.2) | 31 (40.8) | 17 (36.2) | 9 (19.1) | |||

| missing | 29 (61.7) | 42 (55.3) | 29 (61.7) | 36 (76.6) | |||

| Postoperative chemotherapy | None | 8 (17) | 11 (13.1) | 0.519e | 8 (17) | 4 (8.5) | 0.587e |

| IV 5FUl / Oral 5FU | 37 (78.7) | 65 (77.4) | 37 (78.7) | 40 (85.1) | |||

| FOLFOXm / FOLFIRIn | 2 (4.3) | 8 (9.5) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (6.4) | |||

aBMI: body mass index

bCEA: carcinoembryonic antigen

c: Matched variables

dLAR: low anterior resection

e: Fisher’s exact test

fCAA: coloanal anastomosis

gISR: intersphincteric resection

hAPR: abdominoperineal resection

i: Of the 120 and 86 patients respectively who underwent sphincter preserving procedures (low anterior resection or coloanal anastomosis/intersphincteric resection)

jpCR: pathologic complete response

kCRM: circumferential resection margin

lFU: 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin

mFOLFOX: folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin

nFOLFIRI: folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan

Univariable and multivariable analyses for DFS after PSM

Using the selected cohort after PSM (n = 94), univariable and multivariable analyses were performed for DFS. In univariable analysis, pre-CRT CEA, tumor distance from the anal verge, tumor size, ypT, ypN, and combination of pre- and post-NLRs were identified as significant risk factors for DFS. In multivariable analysis, ypT3-4 vs. ypT0-2 [Hazard Ratio (HR) 2.42, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1–5.8, p = 0.048], yp node positive vs. yp node negative (HR 5.6, 95% CI 2.43–12.93, p < 0.001), and pre-NLR<3 & post-NLR<3 vs. control (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.92, p = 0.033) remained as independent prognostic factors for DFS (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariable and multivariable Cox-regression analysis for DFS after PSM (n = 94).

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

| Gender | Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.9 (0.38–2.11) | 0.820 | |||

| Age (years) | < 65 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 65 | 1 (0.43–2.51) | 0.925 | |||

| BMIa (kg/m2) | < 25 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 25 | 0.67 (0.25–1.81) | 0.437 | |||

| cT stage | cT2 | 1 | |||

| cT3 | 2.82 (0.64–12.27) | 0.167 | |||

| cT4 | 3.89 (0.78–19.28) | 0.096 | |||

| cN stage | cN (–) | 1 | |||

| cN (+) | 4.05 (0.95–17.23) | 0.058 | |||

| Pre-CRT CEAb (ng/mL) | < 5 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 5 | 2.3 (1.0–5.14) | 0.042 | |||

| Tumor distance from anal verge (cm) | < 6 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 6 | 2.49 (1.03–6.04) | 0.042 | |||

| Operation name | LARc | 1 | |||

| CAAd & ISRe | 0.55 (0.22–1.32) | 0.185 | |||

| APRf & Hartmann | 1.26 (0.36–4.43) | 0.715 | |||

| Operation time (min) | < 360 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 360 | 1.31 (0.49–3.53) | 0.582 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | < 5 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 5 | 5.28 (1.23–22.7) | 0.025 | |||

| ypT | ypT0-2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ypT3-4 | 3.26 (1.39–7.63) | 0.006 | 2.42 (1–5.8) | 0.048 | |

| ypN | Negative | 1 | 1 | ||

| Positive | 5.88 (2.62–13.19) | <0.001 | 5.6 (2.43–12.93) | <0.001 | |

| CRMg | Positive (≤ 1 mm) | 1 | |||

| Negative (> 1mm) | 1.39 (0.18–10.7) | 0.746 | |||

| missing | 1.31 (0.17–9.76) | 0.792 | |||

| Complications | No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 2.05 (0.92–4.6) | 0.079 | |||

| pre-NLR | < 3 | 1 | |||

| ≥3 | 2.01 (0.86–4.7) | 0.107 | |||

| post-NLR | < 3 | 1 | |||

| ≥3 | 2.08 (0.91–4.77) | 0.081 | |||

| Combination of pre&post NLRs | Control | 1 | 1 | ||

| pre-NLR<3 & post-NLR<3 | 0.37 (0.15–0.89) | 0.027 | 0.37 (0.15–0.92) | 0.033 |

aBMI: body mass index

bCEA: carcinoembryonic antigen

cLAR: low anterior resection

dCAA: coloanal anastomosis

eISR: intersphincteric resection

fAPR: abdominoperineal resection

gCRM: circumferential resection margin

Correlations of neutrophil, lymphocytes, PLR and LMR with DFS and OS

The pre- and post- median values of the neutrophil, lymphocytes, PLR and LMR were shown in S1 Table. Using the median values as the cut-off points, prognostic impact of each variable was investigated. There was no survival difference according to neutrophil, lymphocyte, PLR, and LMR either evaluated in pre- and post- measurements (S2 Table). When we classified patients into the four groups using combination of pre- and post- PLRs and LMRs respectively, Kaplan-Meier plot showed no survival difference between the groups (S1 Fig, Fig 1A–1D). Even when we re-classified those four groups into the two groups, such as pre-PLR<154.4 & post-PLR<255.7 vs. control or pre-LMR<5.42 & post-LMR<3.15 vs. control, there was no survival difference between the two groups. When the patients were dichotomized as pre-LMR≥5.42 & post-LMR≥3.15 vs. control, there was no survival difference between the two groups (S3 Table).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that persistent non-inflammatory status during preop-CRT, assessed by a combination of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios obtained at two different time points, might be associated with low possibility of recurrence in patients with locally advanced non-metastatic rectal cancer who underwent long course preop-CRT followed by surgery.

Previous meta-analysis on the prognostic effect of NLR in patients with rectal cancer showed that elevated NLR was associated with poor survival, with HRs of 13.4 in OS, 4.3 in DFS, and 3.6 in relapse free survival.[22] Nevertheless, several recent studies reported that NLR could not discriminate prognosis in patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer with or without preop-CRT.[26–29] The different impacts of NLR may, to some extent, be explained by weakened predictive power of the NLR due to the narrow spectrum of tumor burden, random error caused by small sample size, or racial differences.[27,29] However, the exact reason for this discrepancy was not clearly depicted. In our study, there was no difference in OS or DFS according to the cut-off value of 3 for pre-NLR. Although DFS was marginally lower in patients with post-NLR > 3, the significance was not sustained in multivariable analysis after propensity score matching. Considering only these results, our study was in line with previous studies reporting the irrelevance of NLR with long-term prognosis in patients with rectal cancer who underwent preop-CRT. However, after combining consecutive values of NLRs during preop-CRT, our cohort can be separated into two distinct groups showing different survival outcomes.

As far as we know, only one study has reported the clinical usefulness of combining pre- and post-NLRs to predict survival outcomes in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent preop-CRT. Sung and colleagues reported that persistently elevated NLRs measured twice during preop-CRT, in comparison to the persistently lower group, showed poor DFS (HR: 4.35, 95% CI: 1.361–13.901, p = 0.013).[32] It should be mentioned that those authors divided their groups using the cut-off points of 1.75 in pre-CRT NLR and 5.14 in post-CRT NLR, as these values were determined to maximize the log-rank test of survival. However, the cut-off value of 1.75 was relatively lower than that used in previous studies, and most patients (72.5%) were allocated into the high pre-CRT NLR group (Table 4). According to the recent analysis of 12,160 healthy Korean people, the mean ± 1.96 standard deviation of NLR was reported to be 1.65 (0.107–3.193).[36] In addition, mean (95% CI) NLR was reported as 2.15 (2.11–2.19) using 9,427 subjects participating in the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey in the USA.[37] As those authors already stated, more supporting data are required to accept those cut-off values in clinical practice.

Table 4. Results of previous studies on NLR in rectal cancer patients with or without preoperative chemoradiotherapy.

| Authors | year/nation | No. of patients (% of CRT) |

Measurement | Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) | Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Cut-off | High NLR | Long term survival outcomes | Pathologic tumor response | ||||

| Carruthers et al.[17] | 2012/UK | 115 (100) | Before CRT | N/A | 5.0 | N/A | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—HR 7.0, 95% CI (2.6–19.2), p = 0.006 DFS—HR 4.1, 95% CI (1.7–9.8), p = 0.03 |

Not evaluated |

| Krauthamer et al.[23] | 2013/Israel | 71 (100) | Before CRT | N/A | 5.0 | 35.2% | Not evaluated | Correlation: (+) High NLR vs. Low NLR: pCR—OR 2.54, 95% CI (1.52–4.18), p = 0.04 (Only in clinical stage III patients, multivariable analysis) |

| Shen L et al.[16] | 2014/China | 199 (100) | Before CRT | 2.4 (1.0–8.9) | 2.8 | 33.2% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—HR 2.123, 95% CI (1.14–3.954), p = 0.018 DFS—HR 1.363, 95% CI (0.840–2.214), p = 0.210 |

Correlation: (-) mean NLR of TRG 0–1 vs. TRG 2–3: 2.68 ± 1.42 vs. 2.82 ± 1.33, p = 0.873 |

| Kim IY et al.[18] | 2014/Korea | 102 (100) | Before CRT | N/A | 3.0 | 24.5% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Cancer specific survival—HR 6.6, 95% CI (1.3–32), p = 0.02 Recurrence free survival—HR 2.8, 95% CI (1.1–6.8), p = 0.03 |

Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: poor pathologic tumor response (ypTNM II-IV)—OR 5.2, 95% CI (1.1–26.5), p = 0.04 |

| After CRT | N/A | 3.0 | 49% | Not evaluated | Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: poor pathologic tumor response (ypTNM II-IV)—p = 0.4 |

|||

| Nagasaki et al.[19] | 2015/Japan | 201(100) | Before CRT | 2.3 (0.8–11.1) | 3.0 | 21.9% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—HR 3.381, 95% CI (1.307–8.751), p = 0.012 RFS—No association |

Not evaluated |

| Caputo et al.[24] | 2016/Italy | 87 (100) | Before CRT | 2.4 (0.9–9.8) | 2.8 | 35.6% | Not evaluated | Correlation: (-) High NLR vs. Low NLR: TRG—p = 0.942 |

| After CRT | 3.7 (1.3–33.4) | 3.8 | 49.4% | Not evaluated | Correlation: (+) High NLR: Higher rates of TRG 4 response—p = 0.033 |

|||

| Hodek et al.[31] | 2016/Czech Republic | 173 (100) | Before CRT | 2.78 (0.64–14.84) | 2.8 | 49.1% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—p = 0.03 DFS—p = 0.20 (univariable analysis) |

Correlation: (-) pCR—p = 0.43 |

| Lee et al.[25] | 2017/Korea | 291 (100) | Before CRT | N/A | 5.0 | 9.6% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Relapse rate—OR 2.4, 95% CI (1.09–5.27), p = 0.025 (univariable analysis) |

Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: pCR—15.3% vs. 0%, p = 0.026 (univariable analysis) |

| After CRT | N/A | 5.0 | 27.1% | Correlation: (-) No detailed data | Correlation: (-) No detailed data | |||

| Sung et al.[32] | 2017/Korea | 110 (100) | Before CRT | 2.1 (0.53–10.63) | 1.75 | 72.7% | Correlation: (+) Pre-NLR≤1.75 & Post-NLR≤5.14 vs. Pre-NLR>1.75 & Post-NLR>5.14: DFS—HR 4.350, 95% CI (1.361–13.901), p = 0.013 |

Correlation: (-) Pre-NLR≤1.75 & Post-NLR≤5.14 vs. Pre-NLR>1.75 & Post-NLR≤5.14 or Pre-NLR≤1.75 & Post-NLR>5.14 vs. Pre-NLR>1.75 & Post-NLR>5.14: pCR—6.9% vs. 13.1% vs. 5%, p = 0.467 |

| After CRT | 3.23 (0.48–21.64) | 5.14 | 19% | |||||

| Kim TG et al.[20] | 2018/Korea | 176 (100) | Before CRT | N/A | 2.0 | 51.7% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—92.4% vs. 71.9%, p = 0.027 DFS—86.8% vs. 70.7%, p = 0.014 (multivariable analysis) |

Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Poor tumor response (Dworak grade 0–2)—OR 2.49, 95% CI (1.264–4.904), p = 0.008 (multivariable analysis) |

| Vallard et al.[21] | 2018/France | 257(100) | Before CRT | N/A | 2.8 | 27.6% | Correlation: (+) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Local recurrence—OR 14.7, 95% CI (1.53–334.3), p = 0.03 Progression-free survival—HR 2.21, 95% CI (1.26–3.86), p = 0.006 Overall survival—HR 2.23, 95% CI (1.14–2.36), p = 0.02 |

Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Good pathologic response (Mandard grade 1–2)-OR 0.53, 95% CI (0.26–1.02), p = 0.06 |

| After CRT | N/A | 2.5 | N/A | Correlation: (-) | Correlation: (-) | |||

| Lino-Silva et al.[26] | 2016/Mexico | 175 (100) | Before CRT | 2.65 ± 1.32* (0.58–6.89) | 3.0 | 17.7% | Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—77.6% vs. 75.9%, p = 0.548 |

Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: pCR—no difference |

| Shen J et al.[27] | 2017/China | 202 (100) | Before CRT | 2.4 (0.6–12.8) | 3.0 | 31.2% | Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: OS—HR 1.066, 95% CI (0.681–1.668), p = 0.779 DFS—HR 0.863, 95% CI (0.536–1.390), p = 0.542 |

Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Good pathologic response (Dworak grade 3–4) - 56.8% vs. 63.4%, p = 0.359 |

| Jung et al.[28] | 2017/Korea | 984 (100) | Before CRT | N/A | 1.7 | 55.5% | Correlation: (-) Low NLR vs. High NLR: Recurrence free survival—HR 1.319, 95% CI(0.978–5.087), p = 0.07 |

Correlation: (-) TRG—p = 0.25 |

| Portale et al.[29] | 2018/Italy | 152 (32.2) | Before CRT or surgery | 2.2 (IQR, 1.7–3.1) | N/A | N/A | Correlation: (-) NLR—Poor discriminative performance: OS—AUC 0.47 DFS—AUC 0.47 |

Not evaluated |

| This study | Korea | 131 (100) | Before CRT | 2.25 (IQR, 1.64–3.29) | 3.0 | 29.8% | Correlation: (+) Control vs. pre-NLR< 3 & post-NLR< 3: DFS—HR 0.37, 95% CI (0.15–0.92), p = 0.033 |

Correlation: (-) pre-NLR< 3 & post-NLR < 3 vs. control: pCR—21.3% vs. 14.9%, p = 0.593 |

| After CRT | 3.46 (IQR, 2.57–4.75) | 3.0 | 60.3% | |||||

Abbreviations: OS: Overall survival, DFS: Disease-free survival, RFS: Relapse free survival, pCR: pathologic complete response, TRG: Tumor regression grade N/A: Not available

*: Mean ± SD, IQR: interquartile range

Although various studies showed the prognostic impact of NLR on survival, there was no consensus for cut-off values of NLR in patients with colorectal cancer. Some authors used an ROC curve to define the optimal cut-off value in which the variable of interest was death or pathologic tumor response.[16,19,25] Other studies decided on a point that could maximize survival differences.[21,28,32] Our cut-off value 3 was also arbitrary and was based on what had been studied or suggested in previous studies on colorectal cancers.[33–35] Nevertheless, the discriminative power of our cut-off value was well demonstrated in various patients with colorectal cancer irrespective of race, which makes our findings more generalizable.

When we divided our cohort into the persistently lower NLR group (group A) versus groups B-D, there was an uneven distribution of baseline characteristics, especially for clinical staging. The persistently lower NLR group (group A) was associated with earlier clinical T staging. Association of high NLR with advanced staging was also observed in other studies. Shen and colleagues reported a significantly higher clinical stage III rate in the high NLR group (95.4%) compared to that of the low NLR group (82.7%) (p = 0.012).[16] In another large-scale study evaluating various blood-derived immune parameters, patients in the high NLR group, which was defined as > 1.7 NLR, had more advanced ypT stage and ypN1 stage.[28] Based on these observations, we cannot exclude the possibility that NLR is a biomarker reflecting an advanced stage. Although the inherent skewness of clinical staging might translate into favorable or poor survival outcomes, we tried to balance clinical staging between the comparative groups using propensity score matching. One strength of this study is the effort to reduce selection bias.

When NLR values measured before starting preop-CRT and after completion of preop-CRT in previous studies were compared (Table 4), the median NLR value measured after completion of CRT is relatively higher than that measured before initiation of CRT (2.4→3.7 in Caputo et al., 2.1→3.23 in Sung et al. respectively).[24,32] In the same sense, some studies reported that the rate of high NLR increased after completion of CRT (24.5%→49% in Kim IY et al., 9.6%→ 27.1% in Lee et al. respectively).[18,25] This phenomenon was also observed in our study. Lee and colleagues reported that neutrophil and lymphocyte counts were maximally decreased 2 weeks after CRT onset in patients with rectal cancer.[30] The neutrophil count increased slightly until the date of surgery; however, the lymphocyte count further decreased until 1 month after commencing preop-CRT. Similarly, Kitayama and colleagues reported that the numbers of neutrophils and monocytes were comparably maintained, while circulating lymphocytes were most markedly decreased during CRT for patients with rectal cancer.[38] Based on these observations, it seems reasonable to assume that decreased peripheral lymphocytes may be one of the major reasons for increased NLR value after completion of preop-CRT. Lymphocytes are the most radio-sensitive cells, and lymphocyte LD50 (lethal dose 50) is among the lowest in the body.[39,40] Reasons for depletion of peripheral lymphocyte after radiation therapy have been suggested as direct irradiation of circulating lymphocytes and/or bone marrow suppression, although the causes of this hematologic response are diverse and remain unknown for rectal cancer.[41]

The physiologic role of lymphocytes is to suppress tumor progression via cytotoxic cell death and cancer immune surveillance.[42] The association of radiation-induced lymphopenia with poor survival has been reported in various solid tumors including brain tumors, head and neck cancer, lung cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cervical cancer.[41] The clinical impact of lymphocyte count during preop-CRT in patients with rectal cancer was investigated to show that sustaining lymphocyte ratio ≥ 0.35 at 4 weeks after commencement of CRT, which was defined as lymphocyte count at 4 weeks divided by baseline lymphocyte count, was an independent predictor of pCR.[43] However, the host response on depletion and/or recovery of circulating lymphocytes during radiation therapy might be different. In our group, among patients who showed pre-NLR <3, 48.9% of patients were categorized into the >3 post-NLR group, while 51.1% of patients stayed in the <3 post-NLR group. The current study could not definitively explain why this kind of hematologic response was different among patients, although the explanation is likely multifactorial. In brief, our results suggest that the preserved host immunity identified during the preop-CRT period can be retained as a long-term effect for patients with rectal cancer, although further studies are needed to validate our findings.

As part of further analyses, we evaluated that the number of neutrophil, lymphocytes, PLR and LMR had some prognostic impact. When we dichotomized our patients into the two separate groups using the median value of pre- and post- measurements, there was no survival difference between the two groups (S1 and S2 Tables). These trends lasted when we sub-divided patients in more detail (S1A–S1D Fig, S3 Table). Some previous studies demonstrated that PLR or LMR had prognostic power in rectal cancer patients who underwent preop-CRT.[28,44–47] Nevertheless, there were some contradictory results[20,48,49] and the cut-off points were heterogeneous among the studies.[44–47] Although our study did not reveal any association between PLR and LMR with survival outcomes, the small sample size of our study and unconfirmed cut-off values might hinder to make a concrete conclusion. It was demonstrated that NLR, PLR and LMR were basically positively correlated with each other.[28,50] Thus, comparing the prognostic impact of PLR, LMR or NLR should be thoroughly investigated and discussed with large populations to exclude the possible interaction between these parameters.

Some limitations of this study have to be acknowledged. The main limitation is derived from the retrospective and single center-based study design. Thus, critical postoperative pathologic outcomes, such as circumferential resection margin, lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion, were not adequately included in final survival analysis. The low specificity of NLR is an inherent limitation of this design. Various conditions, such as hidden infection or pharmacologic response, might influence the value of NLR. Although our study tried to exclude patients with specific conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease-associated rectal cancer, the inherent retrospective nature of this study could not fully exclude patients who had undetectable external sources of inflammatory reaction when blood was sampled. Although the cut-off value used in our study was suggested by previous studies, diverse cut-off values are used in different studies (Table 4). The racial difference of normal NLR values might make it more difficult to generate a universal reference.[6,36,37] The lack of consensus on cut-off values remains a serious problem and hampers clinical utilization of these findings.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that persistent lower NLRs during preop-CRT is associated with low possibility of recurrence after surgery in patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer. Considering the debate on the necessity of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with rectal cancer after preop-CRT, especially for patients with good tumor response,[51,52] our observation might be used to stratify patients for additional treatments. Further studies to validate this hypothesis are needed.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018;68(1):7–30. Epub 2018/01/10. 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hur H, Oh CM, Won YJ, Oh JH, Kim NK. Characteristics and Survival of Korean Patients With Colorectal Cancer Based on Data From the Korea Central Cancer Registry Data. Annals of coloproctology. 2018;34(4):212–21. Epub 2018/09/14. 10.3393/ac.2018.08.02.1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2015. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2018;50(2):303–16. Epub 2018/03/24. 10.4143/crt.2018.143 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rodel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351(17):1731–40. Epub 2004/10/22. 10.1056/NEJMoa040694 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, et al. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355(11):1114–23. Epub 2006/09/15. 10.1056/NEJMoa060829 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolan RD, Lim J, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with operable cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):16717 Epub 2017/12/03. 10.1038/s41598-017-16955-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee MY, Lottsfeldt JL. Augmentation of neutrophilic granulocyte progenitors in the bone marrow of mice with tumor-induced neutrophilia: cytochemical study of in vitro colonies. Blood. 1984;64(2):499–506. Epub 1984/08/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelsey KT, Wiencke JK. Immunomethylomics: A Novel Cancer Risk Prediction Tool. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2018;15(Supplement_2):S76–s80. Epub 2018/04/21. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201706-477MG . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Y, Wang H, Yan A, Wang H, Li X, Liu J, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in determining the prognosis of head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC cancer. 2018;18(1):383 Epub 2018/04/06. 10.1186/s12885-018-4230-z . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethier JL, Desautels D, Templeton A, Shah PS, Amir E. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2017;19(1):2 Epub 2017/01/07. 10.1186/s13058-016-0794-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu JF, Ba L, Lv H, Lv D, Du JT, Jing XM, et al. Association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and differentiated thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2016;6:38551 Epub 2016/12/13. 10.1038/srep38551 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi X, Li J, Deng H, Li H, Su C, Guo X. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for the prognostic assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget. 2016;7(29):45283–301. Epub 2016/06/16. 10.18632/oncotarget.9942 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H, Long F, Jaiswar M, Yang L, Wang C, Zhou Z. Prognostic role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2015;5:11026 Epub 2015/08/01. 10.1038/srep11026 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Zhang W, Feng LJ. Prognostic significance of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in patients with gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(11):e111906 Epub 2014/11/18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0111906 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yodying H, Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S, Sakurazawa N, Yamada M, et al. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Oncologic Outcomes of Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2016;23(2):646–54. Epub 2015/09/30. 10.1245/s10434-015-4869-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen L, Zhang H, Liang L, Li G, Fan M, Wu Y, et al. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (>/ = 2.8) as a prognostic factor for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2014;9:295 Epub 2014/12/19. 10.1186/s13014-014-0295-2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carruthers R, Tho LM, Brown J, Kakumanu S, McCartney E, McDonald AC. Systemic inflammatory response is a predictor of outcome in patients undergoing preoperative chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer. Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2012;14(10):e701–7. Epub 2012/06/27. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03147.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim IY, You SH, Kim YW. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts pathologic tumor response and survival after preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer. BMC surgery. 2014;14:94 Epub 2014/11/20. 10.1186/1471-2482-14-94 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, Fujimoto Y, Konishi T, Nagayama S, Fukunaga Y, et al. Prognostic Impact of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Advanced Low Rectal Cancer Treated with Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy. Digestive surgery. 2015;32(6):496–503. Epub 2015/11/07. 10.1159/000441396 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim TG, Park W, Kim H, Choi DH, Park HC, Kim SH, et al. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in rectal cancer patients following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Tumori. 2018:300891618792476. Epub 2018/08/18. 10.1177/0300891618792476 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallard A, Garcia MA, Diao P, Espenel S, de Laroche G, Guy JB, et al. Outcomes prediction in pre-operative radiotherapy locally advanced rectal cancer: leucocyte assessment as immune biomarker. Oncotarget. 2018;9(32):22368–82. Epub 2018/06/02. 10.18632/oncotarget.25023 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong YW, Shi YQ, He LW, Su PZ. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. OncoTargets and therapy. 2016;9:3127–34. Epub 2016/06/17. 10.2147/OTT.S103031 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krauthamer M, Rouvinov K, Ariad S, Man S, Walfish S, Pinsk I, et al. A study of inflammation-based predictors of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Oncology. 2013;85(1):27–32. Epub 2013/07/03. 10.1159/000348385 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caputo D, Caricato M, Coppola A, La Vaccara V, Fiore M, Coppola R. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) and Derived Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (d-NLR) Predict Non-Responders and Postoperative Complications in Patients Undergoing Radical Surgery After Neo-Adjuvant Radio-Chemotherapy for Rectal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer investigation. 2016:1–12. Epub 2016/10/16. 10.1080/07357907.2016.1229332 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee IH, Hwang S, Lee SJ, Kang BW, Baek D, Kim HJ, et al. Systemic Inflammatory Response After Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy Can Affect Oncologic Outcomes in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Anticancer research. 2017;37(3):1459–65. Epub 2017/03/21. 10.21873/anticanres.11470 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lino-Silva LS, Salcedo-Hernandez RA, Ruiz-Garcia EB, Garcia-Perez L, Herrera-Gomez A. Pre-operative Neutrophils/Lymphocyte Ratio in Rectal Cancer Patients with Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2016;70(4):256–60. Epub 2016/10/06. 10.5455/medarh.2016.70.256-260 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen J, Zhu Y, Wu W, Zhang L, Ju H, Fan Y, et al. Prognostic Role of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2017;23:315–24. Epub 2017/01/20. 10.12659/MSM.902752 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung SW, Park IJ, Oh SH, Yeom SS, Lee JL, Yoon YS, et al. Association of immunologic markers from complete blood counts with the response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy and prognosis in locally advanced rectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):59757–65. Epub 2017/09/25. 10.18632/oncotarget.15760 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portale G, Cavallin F, Valdegamberi A, Frigo F, Fiscon V. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Are Not Prognostic Biomarkers in Rectal Cancer Patients with Curative Resection. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2018;22(9):1611–8. Epub 2018/04/25. 10.1007/s11605-018-3781-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee YJ, Lee SB, Beak SK, Han YD, Cho MS, Hur H, et al. Temporal changes in immune cell composition and cytokines in response to chemoradiation in rectal cancer. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):7565 Epub 2018/05/17. 10.1038/s41598-018-25970-z . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodek M, Sirak I, Ferko A, Orhalmi J, Hovorkova E, Hadzi Nikolov D, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy of rectal carcinoma: Baseline hematologic parameters influencing outcomes. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie: Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft [et al]. 2016;192(9):632–40. Epub 2016/06/09. 10.1007/s00066-016-0988-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sung S, Son SH, Park EY, Kay CS. Prognosis of locally advanced rectal cancer can be predicted more accurately using pre- and post-chemoradiotherapy neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios in patients who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy. PloS one. 2017;12(3):e0173955 Epub 2017/03/16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173955 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiang SF, Hung HY, Tang R, Changchien CR, Chen JS, You YT, et al. Can neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predict the survival of colorectal cancer patients who have received curative surgery electively? International journal of colorectal disease. 2012;27(10):1347–57. Epub 2012/03/31. 10.1007/s00384-012-1459-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malietzis G, Giacometti M, Askari A, Nachiappan S, Kennedy RH, Faiz OD, et al. A preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio of 3 predicts disease-free survival after curative elective colorectal cancer surgery. Annals of surgery. 2014;260(2):287–92. Epub 2013/10/08. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000216 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malietzis G, Giacometti M, Kennedy RH, Athanasiou T, Aziz O, Jenkins JT. The emerging role of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in determining colorectal cancer treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014;21(12):3938–46. Epub 2014/05/29. 10.1245/s10434-014-3815-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JS, Kim NY, Na SH, Youn YH, Shin CS. Reference values of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte-monocyte ratio, platelet-lymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet volume in healthy adults in South Korea. Medicine. 2018;97(26):e11138 Epub 2018/06/29. 10.1097/MD.0000000000011138 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azab B, Camacho-Rivera M, Taioli E. Average values and racial differences of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio among a nationally representative sample of United States subjects. PloS one. 2014;9(11):e112361 Epub 2014/11/07. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112361 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitayama J, Yasuda K, Kawai K, Sunami E, Nagawa H. Circulating lymphocyte number has a positive association with tumor response in neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for advanced rectal cancer. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2010;5:47 Epub 2010/06/08. 10.1186/1748-717x-5-47 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprent J, Anderson RE, Miller JF. Radiosensitivity of T and B lymphocytes. II. Effect of irradiation on response of T cells to alloantigens. European journal of immunology. 1974;4(3):204–10. Epub 1974/03/01. 10.1002/eji.1830040310 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pugh JL, Sukhina AS, Seed TM, Manley NR, Sempowski GD, van den Brink MR, et al. Histone deacetylation critically determines T cell subset radiosensitivity. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950). 2014;193(3):1451–8. Epub 2014/07/06. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venkatesulu BP, Mallick S, Lin SH, Krishnan S. A systematic review of the influence of radiation-induced lymphopenia on survival outcomes in solid tumors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2018;123:42–51. Epub 2018/02/28. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nature reviews Cancer. 2006;6(1):24–37. Epub 2006/01/07. 10.1038/nrc1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heo J, Chun M, Noh OK, Oh YT, Suh KW, Park JE, et al. Sustaining Blood Lymphocyte Count during Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy as a Predictive Marker for Pathologic Complete Response in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2016;48(1):232–9. Epub 2015/03/18. 10.4143/crt.2014.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto A, Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, Oki S, Ide S, Saigusa S, et al. Clinical Implications of Pretreatment: Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio in Patients With Rectal Cancer Receiving Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2019;62(2):171–80. Epub 2018/11/20. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward WH, Goel N, Ruth KJ, Esposito AC, Lambreton F, Sigurdson ER, et al. Predictive Value of Leukocyte- and Platelet-Derived Ratios in Rectal Adenocarcinoma. The Journal of surgical research. 2018;232:275–82. Epub 2018/11/23. 10.1016/j.jss.2018.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abe S, Kawai K, Nozawa H, Hata K, Kiyomatsu T, Morikawa T, et al. LMR predicts outcome in patients after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for stage II-III rectal cancer. The Journal of surgical research. 2018;222:122–31. Epub 2017/12/24. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng YX, Lin JZ, Peng JH, Zhao YJ, Sui QQ, Wu XJ, et al. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio before chemoradiotherapy represents a prognostic predictor for locally advanced rectal cancer. OncoTargets and therapy. 2017;10:5575–83. Epub 2017/12/05. 10.2147/OTT.S146697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gu X, Gao XS, Qin S, Li X, Qi X, Ma M, et al. Elevated Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio Is Associated with Poor Survival Outcomes in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. PloS one. 2016;11(9):e0163523 Epub 2016/09/23. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toiyama Y, Inoue Y, Kawamura M, Kawamoto A, Okugawa Y, Hiro J, et al. Elevated platelet count as predictor of recurrence in rectal cancer patients undergoing preoperative chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. International surgery. 2015;100(2):199–207. Epub 2015/02/19. 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00178.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan JC, Chan DL, Diakos CI, Engel A, Pavlakis N, Gill A, et al. The Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio is a Superior Predictor of Overall Survival in Comparison to Established Biomarkers of Resectable Colorectal Cancer. Annals of surgery. 2017;265(3):539–46. Epub 2016/04/14. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dossa F, Acuna SA, Rickles AS, Berho M, Wexner SD, Quereshy FA, et al. Association Between Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Overall Survival in Patients With Rectal Cancer and Pathological Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Resection. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(7):930–7. Epub 2018/05/02. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park IJ, Kim DY, Kim HC, Kim NK, Kim HR, Kang SB, et al. Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in ypT0-2N0 Patients Treated with Preoperative Chemoradiation Therapy and Radical Resection for Rectal Cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;92(3):540–7. Epub 2015/06/13. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.