Previous studies from our laboratory reported that knockout of some innate immunity genes was associated with increases in the expression of overlapping networks of genes and significant loss of the ability to support the replication of HSV-1; knockout of other genes was associated with decreases in the expression of overlapping networks of genes and had no effect on virus replication. In this report, we document that depletion of GADD45γ reduced virus yields concurrently with significant upregulation of the expression of a cluster of innate immunity genes comprising IFI16, IFIT1, MDA5, and RIG-I. This report differs from the preceding study in an important respect; i.e., the preceding study found no evidence to support the hypothesis that HSV-1 maintained adequate levels of LGP2 or HDAC4 to block upregulation of the cluster of innate immunity genes. We show that HSV-1 causes upregulation of the GADD45γ gene to prevent the upregulation of innate immunity genes.

KEYWORDS: GADD45γ, HSV-1, innate immunity

ABSTRACT

The stress response genes encoding GADD45γ, and to a lesser extent GADD45β, are activated early in infection with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). Cells that had been depleted of GADD45γ by transfection of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or in which the gene had been knocked out (ΔGADD45γ) yielded significantly less virus than untreated infected cells. Consistent with lower virus yields, the ΔGADD45γ cells (either uninfected or infected with HSV-1) exhibited significantly higher levels of transcripts of a cluster of innate immunity genes, including those encoding IFI16, IFIT1, MDA5, and RIG-I. Members of this cluster of genes were reported by this laboratory to be activated concurrently with significantly reduced virus yields in cells depleted of LGP2 or HDAC4. We conclude that innate immunity to HSV-1 is normally repressed in unstressed cells and repression appears to be determined by two mechanisms. The first, illustrated here, is through activation by HSV-1 infection of the gene encoding GADD45γ. The second mechanism requires constitutively active expression of LGP2 and HDAC4.

IMPORTANCE Previous studies from our laboratory reported that knockout of some innate immunity genes was associated with increases in the expression of overlapping networks of genes and significant loss of the ability to support the replication of HSV-1; knockout of other genes was associated with decreases in the expression of overlapping networks of genes and had no effect on virus replication. In this report, we document that depletion of GADD45γ reduced virus yields concurrently with significant upregulation of the expression of a cluster of innate immunity genes comprising IFI16, IFIT1, MDA5, and RIG-I. This report differs from the preceding study in an important respect; i.e., the preceding study found no evidence to support the hypothesis that HSV-1 maintained adequate levels of LGP2 or HDAC4 to block upregulation of the cluster of innate immunity genes. We show that HSV-1 causes upregulation of the GADD45γ gene to prevent the upregulation of innate immunity genes.

INTRODUCTION

A preceding publication from this laboratory reported the effects of cellular gene knockouts on herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) replication and on the expression of a network of genes associated with innate immunity (1). The study elicited two fundamental observations. First, none of the 10 knockout cell lines produced significantly more virus than the parental cell line. Second, two of the cell lines, namely, the cell lines from which LGP2 and HDAC4 had been knocked out, produced significantly less virus than the parental cell line. Concurrently, the two cell lines exhibited significantly higher levels of expression of a cluster of genes associated with innate immunity (1). In this report, we have documented evidence that depletion of the product of a third gene, namely, GADD45γ, also reduced virus yields concurrently with significant upregulation of the expression of a cluster of innate immunity genes comprising IFI16, IFIT1, MDA5, and RIG-I. Depletion of GADD45γ had no effect on the level of expression of LGP2 or HDAC4. This report differs from the preceding study in an important respect. The preceding study found no evidence to support the hypothesis that HSV-1 maintained adequate levels of LGP2 or HDAC4 to block upregulation of the cluster of innate immunity genes (1); in contrast, this report shows that HSV-1 causes upregulation of the GADD45γ gene to prevent the upregulation of innate immunity genes.

GADD45γ is a member of a family of genes that includes two additional members, GADD45α and GADD45β (2–6). Extensive literature links the members of this family to many diverse functions (7–20). Of particular relevance to this study are numerous reports showing that GADD45 family products respond to and may define the outcome of cell stress (7, 11–15).

RESULTS

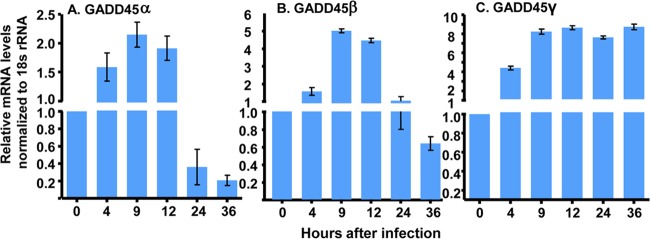

Accumulation of GADD45α, GADD45β, and GADD45γ mRNAs in HEp2 cells infected with HSV-1(F).

HEp2 cells grown on 6-well plates (3 × 105 cells/well) were exposed to 10 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 1 h. The cells were harvested at 0 (mock infected), 4, 9, 12, 24, and 36 h after infection. Total RNA was extracted, and 0.5 μg of each mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, quantified, and normalized with respect to 18S RNA, as described in Materials and Methods. The sequences of the probes and the procedures used in these studies are detailed in Materials and Methods. The results shown in Fig. 1 indicate that the transcription of GADD45β and GADD45γ was enhanced more than 5-fold after infection. The GADD45γ mRNA accumulated earlier and to a higher level than the GADD45β mRNA.

FIG 1.

Accumulation of GADD45α (A), GADD45β (B), and GADD45γ (C) mRNAs in HSV-1(F)-infected HEp2 cells. HEp-2 cells (3 × 105 cells) cultured on 6-well plates were infected or mock infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 1 h. Cells were harvested at 0, 4, 9, 12, 24, and 36 h postinfection. Total RNA was extracted, and 0.5 μg of each RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA, quantified, and normalized with respect to 18S RNA at 0 h, as described in Materials and Methods.

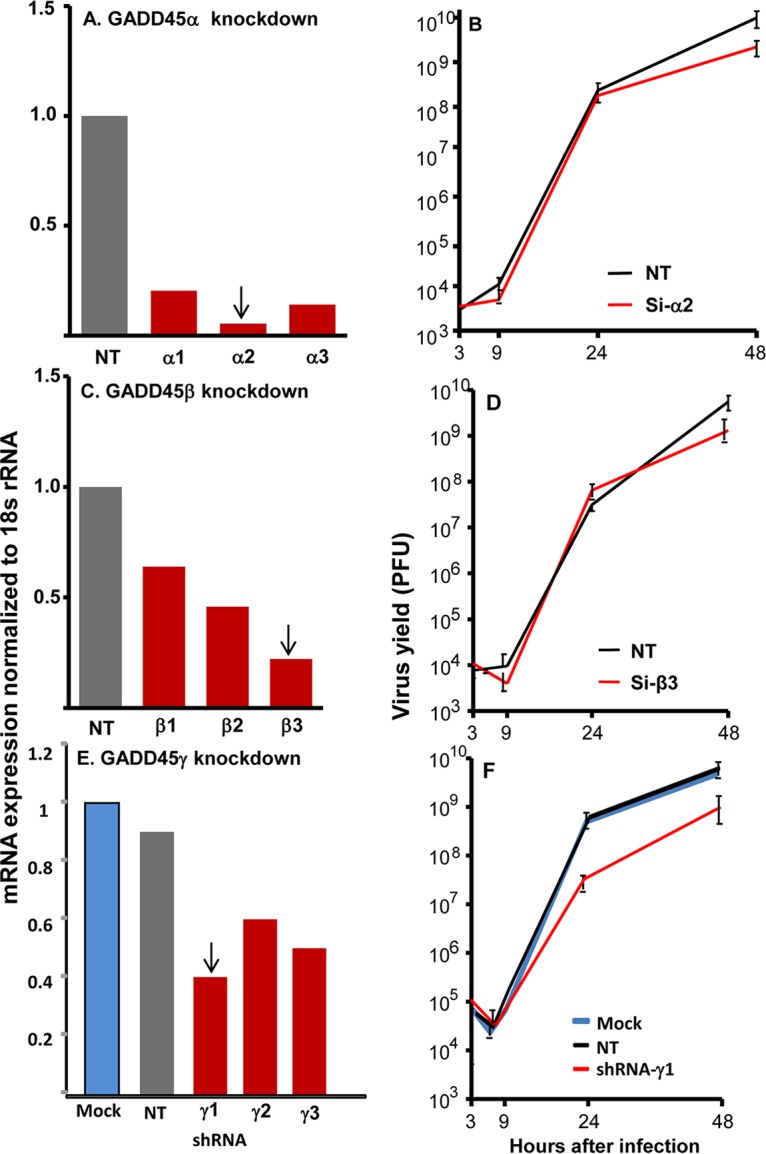

Effects of knockdown of GADD45α, GADD45β, or GADD45γ expression on virus replication.

We report two series of experiments. In the first series, HEp-2 cells seeded on 6-well plates were mock treated or transfected with 1.0 μg of one of three plasmids carrying short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting GADD45α, GADD45β, or GADD45γ or a plasmid carrying nontargeting (NT) shRNA. The cells were harvested at 48 h after transfection. Total RNA was extracted, and 0.5 μg of each RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, quantified, and normalized with respect to 18S RNA. The sequences of the shRNAs and the procedures used in these studies are described in Materials and Methods. On the basis of the results shown in Fig. 2A, C, and E, we selected the shRNAs α2, β3, and γ1 for further studies.

FIG 2.

Depletion of GADD45γ but neither GADD45α nor GADD45β in HEp2 cells resulting in suppression of virus replication. (A and C) Knockdown of GADD45α (A) or GADD45β (C) by transfection of siRNA. HEp2 cells seeded on 6-well plates were transfected with 100 nM NT, GADD45α, or GADD45β siRNA for 48 h. The cells were harvested for RNA isolation and RT-PCR assessment of siRNA efficiency of interference. (B and D) Virus yields from GADD45α-depleted (B) or GADD45β-depleted (D) cells. HEp2 cells seeded on 25-cm2 flasks were transfected with 100 nM NT, GADD45α, or GADD45β siRNA for 48 h and then were infected with 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 2 h. The cells were harvested at 3, 9, 24, and 48 h after infection for virus titration, as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Depletion of GADD45γ by transfection of shRNA. HEp-2 cells (3 × 105 cells) seeded on 6-well plates were either mock treated or transfected with 1.0 μg of three GADD45γ shRNA plasmids or NT shRNA plasmid. The cells were harvested at 48 h after transfection. Total RNA was extracted, and 0.5 μg of each RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA, quantified, and normalized with respect to 18S RNA, as described in Materials and Methods. (F) Virus yields from GADD45γ-depleted cells. Replicate cultures of HEp-2 cells were mock treated (Mock) or treated with 1.0 μg of GADD45γ shRNA plasmid or NT shRNA plasmid. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were exposed to 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell. The inocula were then replaced with fresh medium. The viral progeny were harvested at the times shown and titrated in Vero cells. Arrows indicate the siRNAs or shRNA used for further studies of virus replication (B, D, and F).

In the second series of experiments, HEp-2 cells grown on 6-well plates were mock treated or transfected with 1.0 μg of a plasmid carrying shRNA targeting GADD45α, GADD45β, or GADD45γ or NT shRNA. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were exposed to 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell. The cultures were harvested at 3, 9, 24, or 48 h after infection, and infectious virus was assayed in Vero cells. The results are shown in Fig. 2B, D, and F. In principle, we considered differences in virus yields that were 5-fold or greater to be significant. The results suggest that depletion of GADD45γ negatively affects the replication of HSV-1.

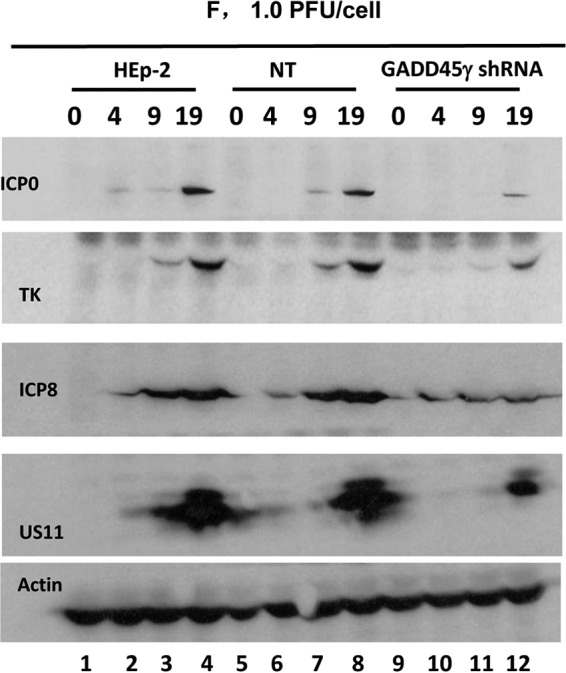

Evidence supporting this conclusion emerged from studies on the accumulation of viral proteins in HEp-2 cells grown on 6-well plates. The cells were mock treated or transfected with 1.0 μg of the γ1 plasmid or a plasmid carrying an NT control. The cells were exposed to 1.0 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell at 48 h after transfection and were harvested at 4, 9, or 19 h after infection. The proteins were electrophoretically separated in a 10% denaturing gel and reacted with the indicated antibodies. Actin served as a loading control. As shown in Fig. 3, all viral proteins tested in this assay accumulated at lower levels in cells transfected with β1 shRNA. On the basis of these results, we elected to focus these studies on the impact of GADD45γ on virus replication.

FIG 3.

Accumulation of selected viral proteins in GADD45γ-depleted cells. HEp-2 cells on 6-well plates were either mock treated or transfected with 1.0 μg of GADD45γ shRNA plasmid or NT shRNA plasmid for 48 h. The cells were then exposed to 1.0 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell and harvested at 4, 9, or 19 h after infection. The proteins were electrophoretically separated in a 10% denaturing gel and reacted with the indicated antibodies. Actin served as a loading control.

Virus replication in a cell line derived from HEp-2 cells from which the GADD45γ gene had been knocked out.

Since the shRNA targeting GADD45γmRNA was only partially effective, for further studies we chose to use a cell line (ΔGADD45γ) derived from HEp-2 cells from which the GADD45γ gene had been knocked out. The procedures for the derivation and verification of the cell line are described in Materials and Methods. The studies on the replication of HSV-1 in the ΔGADD45γ cells may be summarized as follows.

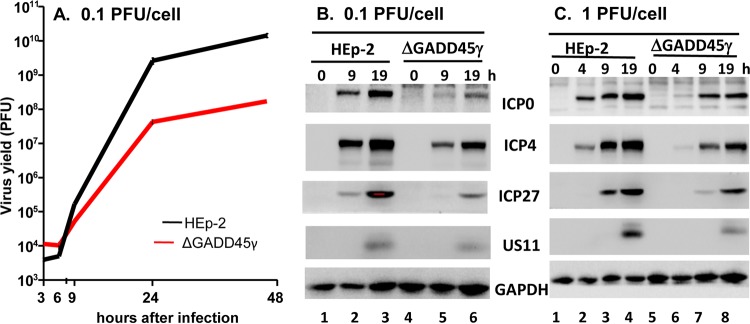

Replicate cultures of HEp-2 or ΔGADD45γ cells were exposed to 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell. The inocula were then replaced with fresh medium. Viral progeny were harvested at the times shown and titrated in Vero cells. The results shown in Fig. 4A indicated that the ΔGADD45γ cells produced 100-fold less virus than the parental HEp-2 cells.

FIG 4.

Accumulation of infectious virus, representative viral proteins, and viral mRNAs in GADD45γ-knockout HEp-2 cells. (A) Virus yields from GADD45γ-knockout cells. Replicate cultures of HEp-2 cells or GADD45γ-knockout (ΔGADD45γ) cells were exposed to 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 2 h. The inoculum was then replaced with fresh medium. Viral progeny were harvested at the times shown and titrated in Vero cells. (B and C) Accumulation of selected viral proteins in GADD45γ-knockout cells. HEp-2 cells or ΔGADD45γ cells either were exposed to 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 2 h and harvested at 9 and 19 h after infection (B) or were exposed to 1.0 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 1 h and harvested at 4, 9, and 19 h after infection (C). The proteins were electrophoretically separated in a 10% denaturing gel and reacted with the indicated antibodies.

Replicate cultures of HEp-2 or ΔGADD45γ cells were exposed to 0.1 PFU (Fig. 4B) or 1.0 PFU (Fig. 4C) of HSV-1(F) per cell and harvested at 9 and 19 h after infection (Fig. 4B) or 4, 9, and 19 h after infection (Fig. 4C). The proteins were electrophoretically separated in a 10% denaturing gel and reacted with the indicated antibodies. The results indicated that the accumulation of viral proteins in ΔGADD45γ cells was both delayed and reduced in amount.

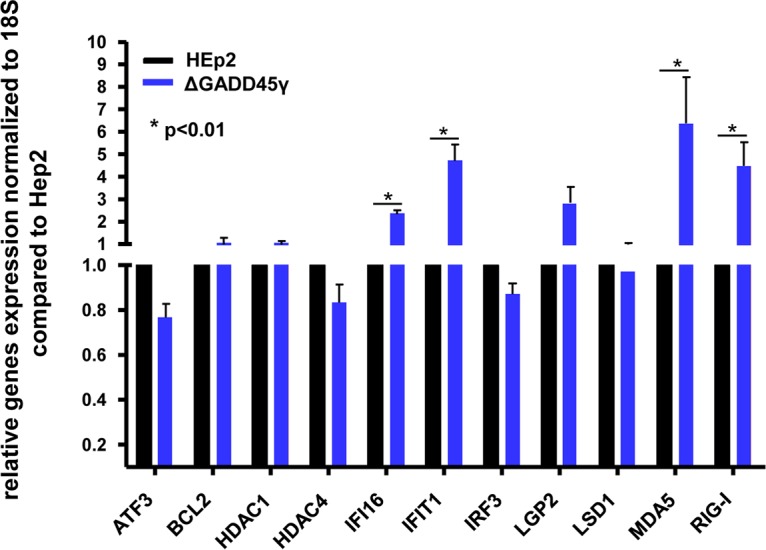

Accumulation of mRNAs for selected cellular innate immunity genes in ΔGADD45γ cells and parental HEp-2 cells.

Total RNA was extracted from HEp-2 or ΔGADD45γ cells grown on 6-well plates and was reverse transcribed as described in Materials and Methods. mRNAs encoding ATF3, BCL2, HDAC-1, HDAC4, IFI16, IFIT1, IRF3, LGP2, LSD1, MDA5, and RIG-I were quantified and normalized with respect to 18S RNA. The results indicated that a cluster of four genes assayed in this study were upregulated in ΔGADD45γ cells (Fig. 5), including the genes encoding IFI16, IFIT4, MDA5, and RIG-1.

FIG 5.

Accumulation of mRNAs of selected cellular genes in GADD45γ-knockout cells and parental HEp2 cells. HEp-2 or GADD45γ-knockout cells were seeded on 6-well plates, and total RNAs were extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA, as described in Materials and Methods. mRNAs encoding ATF3, BCL2, HDAC1, HDAC4, IFI16, IFIT1, IRF3, LGP2, LSD1, MDA5, and RIG-I were normalized with respect to 18S RNA. The results shown are the averages and standard deviations for two independent assays, with three replicate samples each. *, P < 0.01, by Student’s t test.

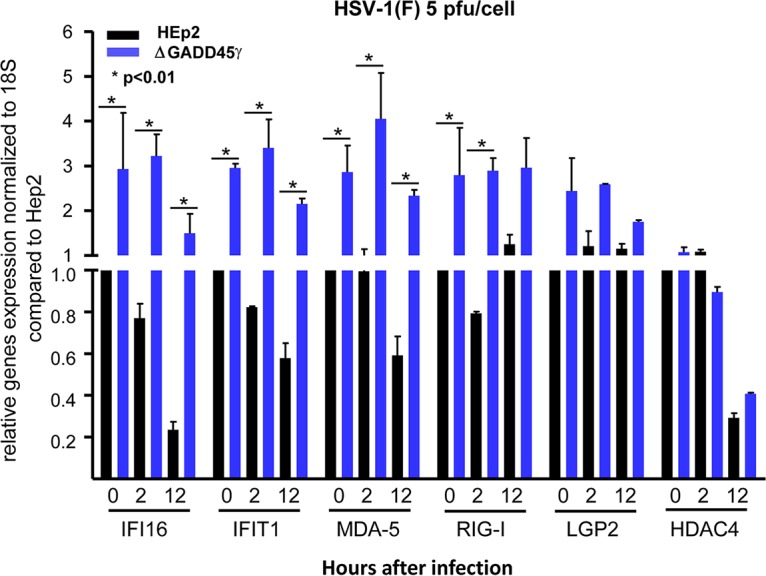

Levels of mRNAs of the innate immunity genes upregulated in uninfected ΔGADD45γ cells remain elevated after infection.

As shown in Fig. 5, we identified four innate immunity genes that were upregulated in uninfected ΔGADD45γ cells. The question posed in the experiments described below is whether the four innate immunity genes upregulated in uninfected ΔGADD45γ cells continued to be upregulated after infection. The second objective of these studies was to determine whether activation of IFI16, IFIT1, MDA5, or RIG-I in ΔGADD45γ cells correlated with repression of LGP2 or HDAC4. The results of the experiments shown in Fig. 5 suggested that the expression of LGP2 or HDAC4 was not affected in uninfected ΔGADD45γ cells. The question posed here is whether the expression of LGP2 or HDAC4 was altered after infection of ΔGADD45γ cells.

In these experiments, HEp-2 orΔGADD45γ cells grown on 6-well plates were mock infected or exposed to 5 PFU of HSV-1 per cell. The cells were harvested at 0 (mock infected), 2, or 12 h after infection, and total RNAs were extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA as described in Materials and Methods. The mRNAs encoding IFI16, IFIT1, LGP2, MDA5, HDAC4, and RIG-I were normalized first with respect to 18S RNA and then with respect to mRNA levels in mock-infected cells. The results shown in Fig. 6 are based on the data garnered from two independent experiments in which each point was based on analyses of three replicate samples. The key feature of the results is that the levels of ΔGADD45γ cell mRNAs encoding IFI16, IFIT1, MDA5, and RIG-I remained significantly higher than the levels of mRNAs detected in infected parental HEp-2 cells. The levels of mRNAs encoding LGP2 or HDAC4 detected in ΔGADD45γ cells were not significantly different from those detected in infected HEp-2 cells.

FIG 6.

Accumulation of selected host genes induced by HSV-1(F) infection in GADD45γ-knockout cells. HEp-2 or GADD45γ-knockout cells were seeded on 6-well plates and were infected or mock infected with 5 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell for 1 h. Cells were then harvested at 2 and 12 h after infection, and total RNAs were extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA, as described in Materials and Methods. mRNAs encoding IFI16, IFIT1, LGP2, HDAC4, MDA5, and RIG-I were normalized with respect to 18S RNA. The results shown are the averages and standard deviations for two independent assays, with three replicate samples each. *, P < 0.01, by Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

In a preceding communication, this laboratory reported the results of studies on a series of cell lines in which a gene related to innate immunity had been knocked out; the genes that were knocked out included LGP2, LSD1, PML, HDAC4, IFI16, PUM1, STING, MDA5, IRF3, and HDAC1 (1). One objective of the study was to determine whether the expression of any of those genes negatively affected the replication of HSV-1. The key findings were 3-fold. (i) None of the knockout cell lines produced significantly more virus that the untreated parental cell line. (ii) In two of the knockout cell lines, namely, ΔLGP2 and ΔHDAC4, the yields of HSV-1 were significantly lower than those obtained from the parental cell line. (iii) Both ΔLGP2 and ΔHDAC4 cell lines exhibited significantly higher levels of expression of a set of innate immunity genes, which we refer to as a network. In essence, the preceding study identified two cellular genes whose expression is essential for optimal replication of HSV-1 (1). In this study, we identified a third gene; knockout of GADD45γ negatively affects the replication of HSV-1.

Relevant to this report are the following. The results presented in this report suggest that GADD45γ acts independently of LGP2 or HDAC4. Thus, the level of expression of LGP2 or HDAC4 is not affected by changes in the expression of GADD45γ, in both uninfected and infected cells. Both LGP2 and HDAC4 are constitutively expressed (1, 21). Activation of innate immunity networks requires active depletion of LGP2 or of HDAC4. The GADD45 family is implicated as stress sensors that modulate the responses of mammalian cells by interacting with other proteins implicated in stress responses. It is not surprising that GADD45 proteins are induced by HSV-1 infection. However, the results presented in this report suggest that the suppression of the innate immunity network by GADD45γ requires activation of the gene by HSV-1.

The most significant finding reported in this and the preceding report (1) is that, in unstressed uninfected cells, the innate immune response to HSV-1 appears to be repressed by at least two mechanisms, i.e., constitutively expressed genes whose products appear to act as repressors and genes (such as GADD45γ) that are activated in the course of virus replication. The data reported here indicate that LGP2 and/or HDAC4 is essential but not sufficient to repress an effective antiviral response. GADD45γ augments this response.

Lastly, GADD45γ is a protein made in response to stress generated by early events in virus replication. Based on the expected function of stress response proteins (7, 11–15), it could be expected that the protein would inhibit rather than enable efficient virus replication. The data suggest that, in this instance, the decision to assist or to block virus replication is defined by viral gene products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

HEp-2 and Vero cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). All cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (HEp-2 cells and GADD45γ-knockout cells) or 5% newborn calf serum (Vero cells). HSV-1(F) was as reported (22). The virus stocks used in these studies were purified as described (23).

Depletion of GADD45α and GADD45β in HEp2 cells by siRNA.

Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Replicate HEp2 cells (3 × 105 cells per well) cultured on 6-well plates were transfected with 100 nM NT, GADD45α, or GADD45β small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for 48 h. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of siRNAs for mRNA depletion

| Gene and name | Sense sequence | Antisense sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GADD45α | ||

| siRNA-1 | GCGAGAACGACAUCAACAUTT | AUGUUGAUGUCGUUCUCGCTT |

| siRNA-2 | GGAGGAAGUGCUCAGCAAATT | UUUGCUGAGCACUUCCUCCTT |

| siRNA-3 | CCGAAAGGGUUAAUCAUAUTT | AUAUGAUUAACCCUUUCGGTT |

| GADD45β | ||

| siRNA-1 | CGGCCAAGUUGAUGAAUGUTT | ACAUUCAUCAACUUGGCCGTT |

| siRNA-2 | GAUGACAUCGCCCUGCAAATT | UUUGCAGGGCGAUGUCAUCTT |

| siRNA-3 | GCAGCAGAAUCUGUUGAGUTT | ACUCAACAGAUUCUGCUGCTT |

| siRNA-NT | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

Depletion of GADD45γ mRNA in HEp2 cells by shRNA interference.

Lentivirus was produced by cotransfection of VSVG, VPR, and pLKO.1 lentiviral vector with inserted GADD45γ shRNA sequences, which are listed in Table 2 (Thermo Scientific). Supernatants containing infectious viral particles were harvested 48 h posttransfection. Infections of exponentially growing cells were performed with virus-containing supernatant supplemented with 8 μg/ml Polybrene. In lentiviral shRNA experiments, transduced cells were continually selected in the presence of puromycin (1 to 2 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

Sequences used to generate shRNAs against GADD45γ and NT scramble control viral vector

| Name | Sequence for shRNA |

|---|---|

| shRNA-1 | CGACTGCACTGCTCTTTCAAA |

| shRNA-2 | TAGATGTGCTGTAGCTGCGAA |

| shRNA-3 | GCAGCAGAAUCUGUUGAGUTT |

| Scramble | CAACAAGATGAGAACGTCCA |

Generation of the GADD45γ-knockout cell line.

Parental HEp-2 cells were cotransfected with the sgRNA vector plasmids targeting the indicated GADD45γ sequences, as follows: sgRNA1#-F, 5′-CACCGCGACATCGACATAGTGCGCG-3′; sgRNA1#-R, 5′-AAACCGCGCACTATGTCGATGTCGC-3′; sgRNA2#-F, 5′-CACCTTTGGCTGACTCGTAGACGC-3′; sgRNA2#-R, 5′-AAACGCGTCTACGAGTCAGCCAAAC-3′. A donor vector containing a selection cassette expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) was inserted into the targeted sites. Selected cells (GFP positive) were serially diluted to form single-cell-derived colonies. The knockout of GADD45γ was further verified by genomic DNA PCR amplified with primers GADD45γ-F (5′-TAGCTGCTGGTTGATCGCACTAT-3′) and GADD45γ-R (5′-CGGGACTGTACTCACCGAAATG-3′). DNA sequencing of the GADD45γ-knockout cell line was confirmed by BLAST searching with the wild-type GADD45γ genomic sequence, deletion of 5′-GCAGGATGCAGGGTGCCGGGAAAGCGCTGCATGAGTTGCTGCTGTCGGCGCAGCGTCAGGGCTGCCTCACTGCCGGCG-3′ on one chromosome, and deletion of 5′-ACTGCCGGCGTCT-3′ on another chromosome (with both deletions resulting in a shift of the GADD45γ reading frame).

Virus titration.

HEp-2 cells were exposed to 0.1 PFU of HSV-1(F) per cell. After 2 h of exposure, the cells were rinsed and reincubated in fresh medium. The cells were harvested at 3, 6, 9, 24, and 48 h after the initial adsorption interval and were gently sonicated to release the virus. The titers of viral progeny were determined in Vero cells.

Total RNA isolation and real-time PCR assays.

Total RNAs were extracted with the aid of TRI Reagent solution (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were standardized by optical density measurements. Cellular cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 μg of total RNA with the aid of a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT kit (Toyobo) in accordance with instructions provided by the suppliers. Cellular DNA copy numbers were then quantified by SYBR green real-time PCR technology (Toyobo), using primers listed in Table 3. All transcripts were normalized with respect to the levels of 18S rRNAs. The assays were performed on a Step One Plus system (Applied Biosystems), and results were analyzed with software provided by the supplier.

TABLE 3.

Sequences of primers for quantitative PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| LGP2 | 5′-GAGCCAGTACCTAGAACTTAAAC-3′ | 5′-ATGGCCCCATCGAGTTTG-3′ |

| RIGs-I | 5′-AGAAGAGTACCACTTAAACCCAG-3′ | 5′-TTGCCACGTCCAGTCAATATG-3′ |

| MDA5 | 5′-AGGAGTCAAAGCCCACCATC-3′ | 5′-GTGACGAGACCATAACGGATAAC-3′ |

| IFIT1 | 5′-CAACCAAGCAAATGTGAG-3′ | 5′-AGGGGAAGCAAAGAAAATGG-3′ |

| HDAC1 | 5′-TTCAAGCTCCACATCAGTC-3′ | 5′-GTCAGGGTCGTCTTCGTC-3′ |

| HDAC4 | 5′-TCAAGAACAAGGAGAAGGGCAAAG-3′ | 5′-TCCCGTACCAGTAGCGAGGGTC-3′ |

| ATF3 | 5′-GCTCTAGAGAAGATGAAAGGAAAAAGAGGCGACGA-3′ | 5′-CCGGAATTCTTAGCTCTGCAATGTTCCTTC-3′ |

| IFI16 | 5′-AAAGTTCCGAGGTGATGC-3′ | 5′-TGACAGTGCTGCTTGTGG-3′ |

| BCL2 | 5′-CTGTGCTGCTATCCTGC-3′ | 5′-TGCAGCCACAATACTGT-3′ |

| IRF3 | 5′-GCCGAGGCCACTGGTGCATAT-3′ | 5′-TGGGTCGTGAGGGTCCTTGCT-3′ |

| LSD1 | 5′-CCGCTCCACGAGTCAAAC-3′ | 5′-ATCCCAGAACACCCGATC-3′ |

| GADD45α | 5′-GAGAGCAGAAGACCGAAAGGA-3′ | 5′-CACAACACCACGTTATCGGG-3′ |

| GADD45β | 5′-GTCGGCCAAGTTGATGAAT-3′ | 5′-CACGATGTTGATGTCGTTGT-3′ |

| GADD45γ | 5′-ACAATGTGACCTTCTGTGT-3′ | 5′-ACTATGTCGATGTCGTTCTC-3′ |

| 18S | 5′-CTCAACACGGGAAACCTCAC-3′ | 5′-CGCTCCACCAACTAAGAACG-3′ |

Immunoblots.

The cells were harvested at the indicated times after infection by scraping into their medium, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), solubilized in RIPA buffer (product no. P0013C; Beyotime) supplemented with the protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; product no. ST506; Beyotime) as specified by the manufacturer, and briefly sonicated. Samples containing 70 μg of protein each were denatured in 5× SDS loading buffer (0.25 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% SDS, 50% glycerol, 0.5 M dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.25% bromophenol blue), boiled for 10 min, electrophoretically separated on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, electrically transferred to a nitrocellulose sheet, blocked, and then reacted overnight at 4°C with the appropriate primary antibodies diluted in PBS with 1% nonfat milk. The protein bands were scanned with an ImageLab scanner (Bio-Rad).

Antibodies.

Antibodies to HSV-1 ICP4 (24), ICP27 (24), ICP0 (24), ICP8 (Rumbaugh Goodwin Institute for Cancer Research), TK (25), and US11 (26) have been reported elsewhere. Other antibodies used in this study included those to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; product no. 2118; Cell Signaling Technology), the His tag (Proteintech Group), and GADD45γ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Shenzhen Science and Innovation Commission Project grant JSGG20160229153415970 and Dapeng Project grant KY20160301 to the Shenzhen International Institute for Biomedical Research and by Guangzhou City Funding grants 1201620304 and 2014A020212346 to Guangzhou Medical University.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu Y, Liu Y, Wu J, Roizman B, Zhou GG. 2018. Innate responses to gene knockouts impact overlapping gene networks and vary with respect to resistance to viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E3230–E3237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720464115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liebermann DA, Hoffman B. 2008. Gadd45 in stress signaling. J Mol Signal 3:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W, Bae I, Krishnaraju K, Azam N, Fan W, Smith K, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. 1999. CR6: a third member in the MyD118 and Gadd45 gene family which functions in negative growth control. Oncogene 18:4899–4907. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beadling C, Johnson KW, Smith KA. 1993. Isolation of interleukin 2-induced immediate-early genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:2719–2723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fornace AJ. 1992. Mammalian genes induced by radiation: activation of genes associated with growth control. Annu Rev Genet 26:507–526. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.002451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdollahi A, Lord KA, Hoffman-Liebermann B, Liebermann DA. 1991. Sequence and expression of a cDNA encoding MyD118: a novel myeloid differentiation primary response gene induced by multiple cytokines. Oncogene 6:165–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvador JM, Brown-Clay JD, Fornace AJ. 2013. Gadd45 in stress signaling, cell cycle control, and apoptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol 793:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8289-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitz I. 2013. Gadd45 proteins in immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol 793:51–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8289-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niehrs C, Schafer A. 2012. Active DNA demethylation by Gadd45 and DNA repair. Trends Cell Biol 22:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamura RE, de Vasconcellos JF, Sarkar D, Libermann TA, Fisher PB, Zerbini LF. 2012. GADD45 proteins: central players in tumorigenesis. Curr Mol Med 12:634–651. doi: 10.2174/156652412800619978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zumbrun SD, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. 2009. Distinct mechanisms are utilized to induce stress sensor gadd45b by different stress stimuli. J Cell Biochem 108:1220–1231. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebermann DA, Hoffman B. 2007. Gadd45 in the response of hematopoietic cells to genotoxic stress. Blood Cells Mol Dis 39:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ying J, Srivastava G, Hsieh WS, Gao Z, Murray P, Liao SK, Ambinder R, Tao Q. 2005. The stress-responsive gene GADD45G is a functional tumor suppressor, with its response to environmental stresses frequently disrupted epigenetically in multiple tumors. Clin Cancer Res 11:6442–6449. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amanullah A, Azam N, Balliet A, Hollander C, Hoffman B, Fornace A, Liebermann D. 2003. Cell signalling: cell survival and a Gadd45-factor deficiency. Nature 424:741–742. doi: 10.1038/424741b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran H, Brunet A, Grenier JM, Datta SR, Fornace AJ, DiStefano PS, Chiang LW, Greenberg ME. 2002. DNA repair pathway stimulated by the forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a through the Gadd45 protein. Science 296:530–534. doi: 10.1126/science.1068712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Zhu H, Murphy TL, Ouyang W, Murphy KM. 2001. IL-18-stimulated GADD45β required in cytokine-induced, but not TCR-induced, IFN-γ production. Nat Immunol 2:157–164. doi: 10.1038/84264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azam N, Vairapandi M, Zhang W, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. 2001. Interaction of CR6 (GADD45γ) with proliferating cell nuclear antigen impedes negative growth control. J Biol Chem 276:2766–2774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh MS, Hollander MC, Fornance AJ. 2000. Role of Gadd45 in apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol 59:43–45. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang XW, Zhan Q, Coursen JD, Khan MA, Kontny HU, Yu L, Hollander MC, O'Connor PM, Fornace AJ, Harris CC. 1999. GADD45 induction of a G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:3706–3711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith ML, Chen IT, Zhan Q, Bae I, Chen CY, Gilmer TM, Kastan MB, O'Connor PM, Fornace AJ. 1994. Interaction of the p53-regulated protein Gadd45 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Science 266:1376–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.7973727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Qu L, Liu Y, Roizman B, Zhou GG. 2017. PUM1 is a biphasic negative regulator of innate immunity genes by suppressing LGP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E6902–E6911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708713114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ejercito PM, Kieff ED, Roizman B. 1968. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behaviour of infected cells. J Gen Virol 2:357–364. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-2-3-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalamvoki M, Du T, Roizman B. 2014. Cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1 export to uninfected cells exosomes containing STING, viral mRNAs, and microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4991–E4996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419338111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackermann M, Braun DK, Pereira L, Roizman B. 1984. Characterization of herpes simplex virus 1 alpha proteins 0, 4, and 27 with monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 52:108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loret S, Guay G, Lippe R. 2008. Comprehensive characterization of extracellular herpes simplex virus type 1 virions. J Virol 82:8605–8618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00904-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roller RJ, Roizman B. 1992. The herpes simplex virus 1 RNA binding protein US11 is a virion component and associates with ribosomal 60S subunits. J Virol 66:3624–3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]