Abstract

The swell of experimental imaging technologies to non-invasively measure immune checkpoint protein expression presents the opportunity for rigorous comparative studies toward identifying a gold standard. 89Zr-atezolizumab is currently in man, and early data show tumor targeting but also abundant uptake in several normal tissues. Therefore, we conducted a reverse translational study, both to understand if tumor to normal tissue ratios for 89Zr-atezolizumab could be improved, and to make direct comparisons to 89Zr-C4, a radiotracer that we showed can detect a large dynamic range of tumor-associated PD-L1 expression. PET/CT and biodistribution studies in tumor bearing immunocompetent and nu/nu mice revealed that high specific activity 89Zr-atezolizumab (~2 μCi/μg) binds to PD-L1 on tumors, but also results in very high uptake in many normal mouse tissues, as expected. Unexpectedly, 89Zr-atezolizumab uptake was generally higher in normal mouse tissues compared to 89Zr-C4, and lower in H1975, a tumor model with modest PD-L1 expression. Also unexpectedly, reducing the specific activity at least 15 fold suppressed 89Zr-atezo uptake in normal mouse tissues, but increased tumor uptake to levels observed with high specific activity 89Zr-C4. In summary, these data reveal that low specific activity 89Zr-atezo may be necessary for accurately measuring PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment, assuming a threshold can be identified that preferentially suppresses binding in normal tissues without reducing binding to tumors with abundant expression. Alternatively, high specific activity approaches like 89Zr-C4 PET may be simpler to implement clinically to measure the broad dynamic range of PD-L1 expression known to manifest among tumors.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction:

The mixed and transient clinical responses to antibody-based immune checkpoint inhibitors have stimulated great interest in identifying biomarkers to predict which patients are most likely to benefit from therapy. Tissue analysis has shown that tumor mutational burden, deficiencies in DNA mismatch repair machinery, and/or checkpoint protein expression can predict favorable outcome1–3. However, these biomarkers generally depend on the analysis of one biopsy from patients with widespread tumor burden, and can bear undesirable false positivity and negativity. On this basis, the molecular imaging field has proposed that a more holistic view of tumor biology among all lesions in a patient might confer more reliable predictive biomarkers.

Predicting tumor responses to checkpoint inhibitors with routine CT and PET/CT has been challenging as progressive disease is often difficult to distinguish from responsive disease early after the initiation of therapy4,5. For instance, edema or necrosis following T cell recruitment to the tumor microenvironment can cause a tumor enlargement that mimics progression on CT. Moreover, 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose (FDG) is avidly consumed by activated lymphocytes, and the increase in 18F-FDG accumulation in the tumor microenvironment after effective therapeutic intervention is challenging to distinguish from elevated radiotracer uptake due to progressing tumors. In both cases, observing clear radiographic tumor responses often requires imaging several months post therapy.

Many groups have responded to this challenge by developing experimental molecular imaging technologies targeting checkpoint proteins, antigens specific to T cell populations (e.g. CD4, CD8), or biological events upregulated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (e.g. nucleotide salvage pathways, granzyme B)6,7. On the leading edge of clinical translation are several protein-based radiotracers targeting PD-L1, including 89Zr-atezolizumab (atezo), 89Zr-avelumab, and the adnectin 18F-BMS-9861928,9. The first available clinical data from 16 patients receiving 89Zr-atezo support the expected diversity of PD-L1 expression levels in clinical disease (SUVmax between 1.6 and 46), and underscore the potential utility of imaging to holistically measure checkpoint protein expression over a patient’s entire tumor burden. Notably, high radiotracer uptake was also observed in many PD-L1 rich normal tissues (e.g. the liver, spleen, kidneys, lymph nodes, and intestines). Whether radiotracer sequestration in normal tissues interferes with measurement of PD-L1 on tumors is unclear.

These considerations motivated us to conduct reverse translational studies with 89Zr-atezo to understand whether the measurement of tumor-associated PD-L1 expression could be improved, as well as to begin assessing its relative strengths and weaknesses compared to 89Zr-labeled C4, a recombinant human anti-PD-L1 IgG1 that detects tumor associated antigen with little “background” in normal mouse tissues. Like atezo, C4 has low nM affinity for an epitope on the ectodomain of natively expressed human and mouse PD-L1 (EC50 = 5.5 nM and 6.6 nM, respectively). Moreover, functionalization of C4 with desferrioxamine (DFO) for imaging did not pejoratively impact its affinity (IC50 = 5.2 nM, 9.9 nM for natively expressed mouse and human PD-L1, respectively), or the immunoreactive fraction (~93%). Although atezo has been previously radiolabeled with Cu-64 and In-111, directly comparing the existing preclinical biodistributon data to those for 89Zr-C4 is challenging, as differences in bioconjugation chemistries and the biological fates of the catabolized radiometals can impact biodistribution in a manner unrelated to the properties of the respective antibodies10–12. Moreover, biodistribution studies with 89Zr-C4 were conducted in immunocompetent C57BL/6J and T cell deficient nu/nu mice, while studies with 64Cu- and 111In-atezo were conducted in severely immunodeficient NSG mice. As a recent study elegantly demonstrated, the immune status of laboratory mice can dramatically impact immunoglobulin biodistribution in normal tissues of relevance to PD-L1 like the spleen and bone through CDR-independent mechanisms13. Therefore, a more systematically comparison of the characteristics 89Zr-atezo and 89Zr-C4 is warranted.

Results and Discussion:

Synthesis and in vitro characterization of 89Zr-labeled Atezolizumab.

Atezo was conjugated to the chelator desferrioxamine B (DFO) by reacting commercial para-isothiocyanatobenzyl-DFO with solvent exposed ε-amino groups on lysine residues. The affinity of DFO-atezo for the recombinant human ectodomain of PD-L1 was assessed ex vivo using biolayer interferometry (Fortebio, Octet Red384 system), and the KD of the DFO-conjugated antibody was equivalent to naked atezo (1.8±0.09 nM and 1.9±0.2 nM, respectively). The chelate number per molecule of atezo was determined to be 2.26 ± 0.5 (Figure S1A). DFO-atezo was radiolabeled via incubation with 89Zr-oxalic acid for 120 min and purified using size exclusion chromatography. The radiochemical yield was consistently >95%, the radiochemical purity >98%, and the specific activity was 2.28 ± 0.4 μCi/μg over 5 independent radiosyntheses (Figure S1B). These values all compared favorably to those we achieved and reported for 89Zr-C4, including a specific activity of ~7 μg/μg.

A comparison of the biodistribution of 89Zr-Atezo and 89Zr-C4 in tumor bearing immunocompetent and T cell deficient nu/nu mice.

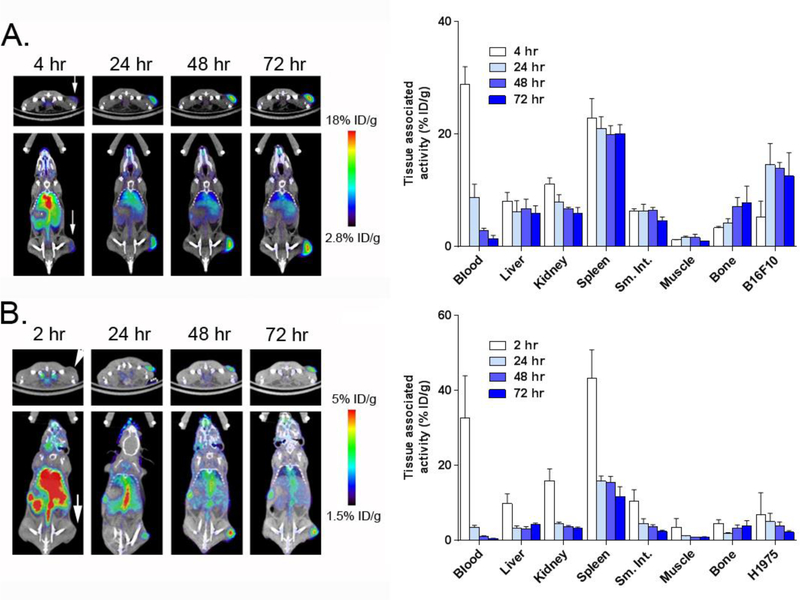

The biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo was first evaluated in immunocompetent C57BL/6J mice bearing subcutaneous B16 F10 tumors, a PD-L1 expressing mouse melanoma model that we previously showed to harbor high avidity for 89Zr-C4. At a specific activity of 1.53 μCi/μg, 89Zr-atezo had overall high accumulation in blood rich abdominal tissues at early time points post injection, which generally declined from 24 – 72 hours, as expected (Figure 1A and Figure S2). Blood associated activity also decreased from 4 – 48 hours. Persistent retention of 89Zr-atezo from 24 – 72 hours was observed in the spleen, liver, kidney, lungs, small intestine, and bone. Uptake in the tumor increased from 4–24 hours, and remained constant at ~13% ID/g out to 96 hours (Figure S2). A separate cohort of tumor bearing mice were treated with 89Zr-atezo subjected to heat denaturation immediately prior to injection. Radiotracer accumulation in B16 F10 tumors was significantly reduced by heat denaturation, as expected (Figure S3).

Figure 1. A summary of the biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo over time in tumor bearing animals.

A. ImmunoPET (left) and biodistribution studies (right) from selected tissues shows the accumulation of 89Zr-atezo in intact male C57BL/6J mice with subcutaneous B16F10 tumors. Persistently high uptake of the radiotracer was observed in the tumor, spleen, liver and kidney. The location of the tumor on PET/CT is indicated with a white arrow. 89Zr-atezo was administered at a specific activity of 1.53 μCi/μg. B. ImmunoPET (left) and biodistribution studies (right) from selected tissues shows the accumulation of 89Zr-atezo in intact male nu/nu mice with subcutaneous H1975 tumors. Similar qualitative trends in the biodistribution of normal tissues were observed compared to the data collected from C57BL/6J mice. Tumor uptake in H1975 was lower than that observed in B16F10 tumors, consistent with the relative expression levels of PD-L1. The location of the tumor on PET/CT is indicated with a white arrow. 89Zr-atezo was administered at a specific activity of 2.17 μCi/μg.

We next evaluated the biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo in immunocompromised intact male nu/nu mice bearing H1975 tumors, a human non-small cell lung cancer model with ~2.5 fold lower endogenous PD-L1 levels compared to B16 F1014. At a specific activity of 2.17 μCi/μg, the pattern of radiotracer biodistribution in normal tissues from 2 – 72 hours was qualitatively similar to what was observed in C57Bl/6J mice, with the highest uptake observed in the spleen, liver, kidney, lung, small intestine, and bone. The retention of 89Zr-atezo in H1975 tumors was above blood and muscle as early as 24 hours post injection, and ~3.5 fold lower than B16 F10 (Figure 1B and Figure S4). Moreover, the tumor to blood and tumor to muscle ratios from both mouse strains suggested that optimal tumor detection requires at least 48 hours of uptake time (Table 1). Of note, 89Zr-atezo retention was generally lower in the normal mouse tissues of nu/nu mice versus C57BL/6J. Since the specific activity of the 89Zr-atezo formulation was higher in the nu/nu mouse cohort, the lower uptake likely reflects the reduced T cell content of athymic nu/nu mice (Table 2).

Table 1.

A summary of the tumor to blood and tumor to muscle ratios derived from the biodistribution studies with 89Zr-atezo outlined in Figure 1. Data referring to B16F10 tumors were acquired in the C57BL/6J mouse strain, while data for H1975 were acquired in nu/nu mice.

| Tumor:Blood | Tumor:Muscle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16 F10 | H1975 | B16 F10 | H1975 | |

| 24 hours | 1.76 ± 0.4 | 1.46 ± 0.2 | 8.97 ± 1.3 | 4.32 ± 0.4 |

| 48 hours | 4.89 ± 0.6 | 3.96 ± 0.8 | 9.33 ± 3.2 | 4.79 ± 0.4 |

| 72 hours | 10.25 ± 4.1 | 4.00 ± 0.6 | 13.06 ± 0.7 | 2.64 ± 0.4 |

Table 2. A summary of the biodistribution data for 89Zr-atezo and 89Zr-C4 in tumor bearing mice at 48 hours post injection.

Immunocompetent intact male C57Bl/6J mice were inoculated subcutaneously with B16F10 in the flank, and immunocompromised athymic male nu/nu mice received subcutaneous H1975 tumors in the flank. C4 uptake in normal tissues was generally lower that atezo, with the notable exception of the liver and kidney. Abbreviations: Lg. Int. = large intestine, Sm. Int. = small intestine, N/A = not applicable. The specific activity of 89Zr-atezo was 1.53 μCi/μg (B16 F10) and 2.17 μCi/μg (H1975). The specific activity of 89Zr-C4 was previously determined to be 7 μCi/μg.

| Tissue | 89Zr-atezo | 89Zr-C4 | 89Zr-atezo | 89Zr-C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 2.87 ± 0.4 | 2.17 ± 0.3 | 1.02 ± 0.2 | 2.87 ± 0.6 |

| Heart | 3.93 ± 0.3 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 1.85 ± 0.3 | 1.08 ± 0.1 |

| Lung | 8.59 ± 0.8 | 0.89 ± 0.1 | 5.53 ± 0.9 | 1.79 ± 0.3 |

| Liver | 6.79 ± 1.6 | 7.33 ± 1.1 | 3.15 ± 0.5 | 8.16 ± 0.6 |

| Kidney | 6.71 ± 0.3 | 2.76 ± 0.8 | 3.60 ± 0.4 | 4.28 ± 0.7 |

| Spleen | 19.95 ± 1.5 | 6.05 ± 0.2 | 15.51 ± 1.6 | 6.48 ± 1.0 |

| Pancreas | 1.85 ± 0.2 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 1.03 ± 0.07 | 0.57 ± 0.06 |

| Lg. Int. | 2.83 ± 0.3 | 0.68 ± 0.3 | 1.57 ± 0.2 | 0.51 ± 0.1 |

| Sm. Int. | 6.44 ± 0.5 | 0.59 ± 0.1 | 3.59 ± 0.6 | 0.73 ± 0.3 |

| Stomach | 1.75 ± 0.5 | 0.36 ± 0.1 | 0.89 ± 0.2 | 0.44 ± 0.1 |

| Muscle | 1.63 ± 0.6 | 0.73 ± 0.3 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.47 ± 0.06 |

| Bone | 7.11 ± 1.64 | 2.62 ± 0.3 | 3.31 ± 0.8 | 2.87 ± 0.3 |

| Brain | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.1 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| B16 F10 | 13.92 ± 1.0 | 13.83 ± 0.5 | N/A | N/A |

| H1975 | N/A | N/A | 3.97±1.0 | 7.08±0.8 |

A comparison of the biodistribution patterns between 89Zr-atezo and 89Zr-C4 showed that accumulation of both radiotracers in B16 F10 tumors was equivalent, while uptake of 89Zr-atezo was significantly lower in H1975 tumors compared to 89Zr-C4 (Table 2, and Figures S2 and S4). This was accompanied by higher levels of 89Zr-atezo in virtually all normal mouse tissues compared to 89Zr-C4, suggesting that there may be a “sink effect” imparted by normal mouse tissues that prevents 89Zr-atezo from engaging the relatively modest levels of PD-L1 expressed on H1975. To test this hypothesis more systematically, we next evaluated the impact of added carrier (i.e. unlabeled atezo) on the biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo.

Investigating the impact of added carrier on the biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo.

To identify the optimal carrier concentration, we first compared our preclinical biodistribution values to the available human data for 89Zr-atezo. The human data showed equivalent accumulation of 89Zr-atezo in normal organs like the spleen (~18% ID/kg), liver (~7% ID/kg), kidney (~5% ID/kg), and intestines (~5% ID/kg). That the clinical formulation consisted of 1 mg 89Zr-atezo with 10 mg of carrier added, and the mouse studies were conducted with carrier free 89Zr-atezo, suggested to us that increasing carrier beyond 10 molar excess may be required to impact 89Zr-atezo biodistribution in mice.

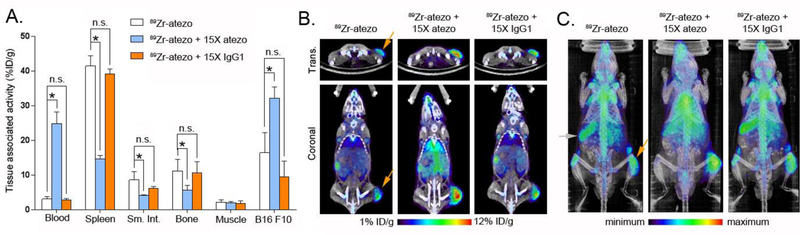

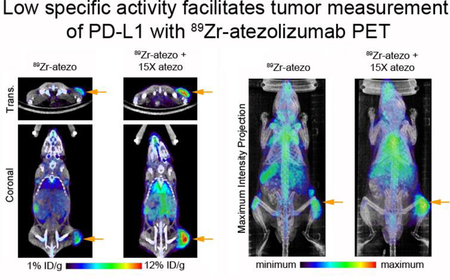

On this basis, immunocompetent mice bearing subcutaneous B16 F10 tumors were co-injected with 89Zr-atezo (specific activity = 2.45 μCi/μg) or 89Zr-atezo with 15x excess unlabeled atezo (specific activity = 0.16 μCi/μg). At 48 hours post injection, added carrier significantly reduced 89Zr-atezo uptake in the spleen, small intestine, and bone (Figure 2A and Figure S5). The carrier also increased 89Zr-atezo levels to a statistically significant extent in B16 F10 tumors. Further increasing the dose of added carrier to 30x in a separate cohort of mice only marginally improved the tumor to normal tissue ratios (Table 3). To further understand the mechanistic basis of tracer redistribution by carrier, an additional cohort of mice were co-injected with 89Zr-atezo (specific activity = 2.45 μCi/μg) and 15x molar excess of an IgG1 isotype control. The isotype control did not alter 89Zr-atezo biodistribution in normal or tumor tissues at 48 hours post injection, strongly suggesting the added atezo carrier impacts radiotracer biodistribution through epitope/CDR interactions (Figure 2A and Figure S5). Inspection of the PET/CT imaging data and maximum intensity projections showed that the atezo carrier effects on radiotracer biodistribution were visually obvious and consistent with the biodistribution data (Figure 2B and 2C).

Figure 2. Added atezo carrier redistributes 89Zr-atezo from normal tissues to tumors via a CDR-dependent mechanism.

A. Biodistribution data acquired 48 hours post injection in immunocompetent C57BL/6J mice with subcutaneous B16F10 xenografts show that 15x atezo carrier suppresses 89Zr-atezo uptake in normal PD-L1 rich mouse tissues, while tumor uptake of the radiotracer increases. In contrast, co-administration of 15x excess unlabeled non-targeting human IgG1 isotype control does not alter the biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo, suggesting that the redistribution requires CDR interaction with its epitope on PD-L1. 89Zr-atezo was prepared and used at a specific activity of 2.45 μCi/μg prior to dilution with atezo or IgG1 isotype control. *P < 0.01, n.s. = not significant. B. Representative coronal and transverse PET/CT images of mice from each treatment arm 48 hours post injection show the impact of added naked atezo carrier on tumor uptake of 89Zr-atezo. The tumor is located on the right hind limb on each mouse and highlighted in the 89Zr-atezo treatment arm with an orange arrow. C. Maximum intensity projections of the same mice also capture the redistribution of 89Zr-atezo due to added atezo, but not non-targeting IgG1 isotype control. The position of the tumor is highlighted with an orange arrow, and the position of the spleen is highlighted with a gray arrow.

Table 3.

A summary of the impact of added atezo carrier on the biodistribution of 89Zr-atezo in immunocompetent C57Bl/6J mice bearing B16 F10 xenografts. Significant elevation of the tumor to normal tissue ratio was observed due to co-injection with 15x or 30x molar excess of naked atezo compared to carrier free 89Zr-atezo (specific activity = 2.75 μCi/μg). The improvement was driven both by suppression of 89Zr-atezo binding in normal tissues, and elevation of 89Zr-atezo accumulation in tumor. No significant improvement in ratios was noted by elevating the dose of carrier from 15x to 30x. All data were collected 48 hours post injection of radiotracer formulation. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation.

| Molar excess of added atezo carrier | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 | 30 | |

| Tumor:Spleen | 0.64 ± 0.7 | 1.68 ± 0.1 | 1.42 ± 0.4 |

| Tumor:Sm.Int. | 2.35 ± 0.3 | 7.01 ± 0.2 | 10.55 ± 2.7 |

| Tumor:Bone | 2.29 ± 0.5 | 5.07 ± 1.0 | 6.53 ± 2.1 |

| Tumor:Muscle | 15.28 ± 0.9 | 15.82 ± 2.1 | 18.47 ± 2.2 |

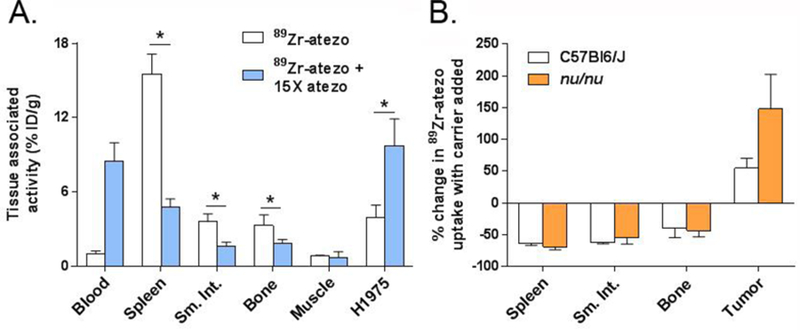

A separate cohort of nu/nu mice bearing subcutaneous H1975 tumors were treated with 89Zr-atezo (specific activity = 2.5 μCi/μg) or 89Zr-atezo with 15x molar excess naked atezo (specific activity = 0.16 μCi/μg). At 48 hours post injection, added carrier suppressed radiotracer uptake in normal mouse tissues, as expected, while elevating radiotracer uptake in the tumors (Figure 3A and Figure S6). The relative suppression of 89Zr-atezo uptake in normal tissues due to added carrier was essentially equivalent in both mouse strains, further underscoring that carrier added effects are likely due to interactions between the CDR and PD-L1 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Added atezo carrier substantially elevates 89Zr-atezo uptake in H1975 tumors in the T cell deficient nu/nu background.

A. A summary of the biodistribution values for 89Zr-atezo co-injected with 15x molar excess unlabeled atezo in nu/nu mice with subcutaneous H1975 tumors. As with the study in immunocompetent mice, radiotracer uptake was suppressed in PD-L1 rich normal tissues, and elevated in the tumor. The biodistribution data were collected 48 hours post injection. 89Zr-atezo was prepared at a specific activity of 2.5 μCi/μg prior to use with or without added atezo. *P<0.01 B. A bar graph representing the percent change in radiotracer uptake due to added carrier among the immunocompetent and immunocompromised mouse cohorts. Suppression of 89Zr-atezo uptake in normal mouse tissues by carrier atezo was substantial and equivalent among two mouse strains.

These reverse translational studies with 89Zr-atezo have revealed a special importance for lower specific activity to measure tumor-associated PD-L1, especially for tumors with modest antigen expression. This finding is not obvious based on previous reports describing the biodistribution of 64Cu-atezo and 111In-atezo. For instance, very high doses (1.5 mg) of naked atezo suppressed binding of 64Cu-atezo (specific activity ~8 μCi/μg) to MDA MB 231 tumors at 24 hours post injection (excess atezo did not alter the biodistribution in SUM149 tumors implanted in the same mice, despite equivalent radiotracer uptake in each tumor model at 24 hours post injection) 11. Moreover, statistically significant blocking effects were not reported in the normal tissues of NSG mice, and 1.5 mg atezo actually elevated splenic uptake of 64Cu-atezo. Combining lower doses of naked atezo with 111In-atezo (specific activity of ~5 μCi/μg) showed a qualitatively similar biodistribution trend to 89Zr-atezo; however, predicting the clinical relevance of these data is challenging as these studies were conducted in NSG mice bearing CHO tumors with engineered PD-L1 overexpression12. The biodistribution data for 89Zr-atezo in more clinically relevant mouse strains bearing tumors with a range of endogenous rather than artificially overexpressed PD-L1 should firmly underscore the importance of specific activity to antigen measurement in tumors.

Measuring PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment with non-invasive imaging is an unusual clinical challenge, as it need not be overexpressed compared to normal tissues to promote tumor growth, and patients with as little as 1% of PD-L1 positive cells on immunohistochemistry can experience durable clinical responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies. Therefore, the ideal non-invasive companion diagnostic should be capable of measuring the largest possible dynamic range of PD-L1 expression to accommodate the diversity of antigen expression that presents clinically. Whether 89Zr-atezo can realize this goal will require a trial to determine if a specific activity can be identified that reveals antigen on tumors with low expression without blocking binding to tumors with abundant antigen expression. Alternatively, 89Zr-C4 may be more straightforward to implement clinically, as high specific activity formulations result in higher binding to tumor with lower “background” in normal tissues compared to 89Zr-atezo. Why 89Zr-C4 differs from 89Zr-atezo in this regard is currently unclear to us. The difference is likely not related to recognition of discrete subpopulations of endogenous PD-L1, as we found that unlabeled atezo or C4 were both effective, albeit to different extents, at suppressing the binding of 89Zr-atezo to natively expressed PD-L1 on B16F10 cells in vitro (Figure S7). We are currently working to understand the basis for the biodistribution differences further, as well as to prepare 89Zr-C4 for a clinical trial in which its ultimate utility can be assessed. Moreover, the findings from this study argue strongly for further studies to determine if tumor measurement of PD-L1 by emerging low molecular weight constructs also requires low specific activities15.

Materials and Methods:

General Methods:

B16 F10 and H1975 cells were acquired from ATCC and subcultured according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Para-isothiocyanatobenzyl-DFO was obtained from Macrocyclics (Dallas, TX) and used without further purification. Zirconium-89 was purchased from 3D Imaging, LLC (Maumelle, AR). The non-targeting human IgG1, isolated from human myeloma plasma (cat. no. 400120), was acquired from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA).

Antibody generation and characterization:

The sequence of atezolizumab was taken from the International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances. The Fc region of the antibody was modified to abolish Fc gamma receptor binding as described16. The antibody was expressed in HEK293–6E cells and purified by Protein A resin following standard protocols. C4 was expressed and purified as previously described14.

Kd calculation:

Kinetic constants for atezolizumab antibody against human PD-L1 (Sino Biological Inc.) were determined using an Octet RED384 instrument (ForteBio). Five concentrations of human PD-L1 (250 nM, 100 nM, 50 nM, 10 nM and 5 nM were tested for binding to atezolizumab or atezolizumab conjugated with DFO immobilized on Anti-Human IgG Fc Capture biosensors (Fortebio). All measurements were performed at room temperature in 384-well microplates and the running buffer was PBS with 0.5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20. Atezolizumab was loaded for 180 s from a solution of 300 nM, baseline was equilibrated for 60 s, and then the antigens were associated for 600 s followed by 1200 s disassociation. Between each sample, the biosensor surfaces were regenerated three times by exposing them to 10 mM glycine, pH 1.5 for 5 s followed by PBS for 5 s. Data were analyzed using a 1:1 interaction model on the ForteBio data analysis software 8.2.

Bioconjugation chemistry:

Atezo (272 μL at a concentration of 5.51 mg/mL) was dissolved in 200 μL of 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.0). The final reaction mixture was adjusted to a total volume of 0.5 mL by adding a sufficient amount of 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer. Para-Isothiocyanatobenzyl-desferrioxamine (p-Df-Bz-NCS, 30 mM in DMSO, 4 eq.) was added to the antibody solution dropwise while mixing vigorously. The final concentration of DMSO was kept below 2% (v/v) to avoid any precipitation. The reaction was allowed to incubate for 30 min at 37oC, whereupon the reaction mixture was purified with a PD-10 column using an ammonium acetate mobile phase (0.2 M sodium acetate, pH 7.0). The atezo-DFO solution was aliquoted and stored at −20o C until time of use.

Chelate number determination:

The number of DFO molecules attached to atezo was measured with a radiometric isotopic dilution assays. From a stock solution, aliquots of 89Zr-oxalate (10 μCi in 50 μL, pH = 7.7–7.9) were added to 7 solutions containing 1:4 serial dilutions of nonradioactive ZrCl4 (100 μL fractions; 1000–0.5 pmol, pH 7.7). The mixture was vortexed for 30 seconds before adding 5 μL aliquots of DFO-atezo in sterile PBS (1.95 mg/mL, 9.75 μg of mAb). The reactions were incubated at room temperature for >2 h before quenching with DTPA (20 μL, 50 mM, pH7.0). The extent of complexation was assessed by iTLC. The fraction of free 89Zr was plotted versus the amount of non-radioactive ZrCl4 added. The number of chelates was calculated by measuring the concentration of ZrCl4 at which only 50% of the protein was labeled, multiplying by a factor of 2, and then dividing by the moles of protein present in the reaction. Isotopic dilution assays revealed an average of 2.26 ±0.5 accessible chelates per protein molecule for atezo.

Radiochemistry:

The following is a representative protocol, which resulted in an average specific activity = 2.28 ± 0.4 μCi/μg. A solution of 89Zr-oxalic acid (5mCi; 40 μl) was neutralized with 2 M Na2CO3 (18 μl). After 3 min, 0.30 ml of 0.5 M HEPES (pH 7.1–7.3) and 1.5 mg of DFO-atezo (pH = 7) were added into the reaction vial. After incubation for 60 min at 37oC, the reaction progress was monitored by iTLC using a 20 mM citric acid (pH 4.9–5.1) mobile phase. The decay corrected radiochemical yield was consistently > 95%.

Cellular receptor binding assays:

Cells were seeded at a density of 4×105 cells per well in 12-well plates. On the day of the experiment, cells were subjected to a PBS wash followed by incubation for 1 hour at 37oC, 5% CO2 in PBS with89Zr-atezo (0.5 μCi), or 89Zr-atezo with 10x unlabeled atezo or C4. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4oC, whereupon the media was removed, and the residual unbound radiotracer was removed with two washes with ice cold PBS. The cell bound activity was harvested by lysis in 1 mL of 1M NaOH and collected. The unbound and cell-associated fractions were counted in a gamma counter and expressed as a percentage of the total activity added per well per cell number. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Small animal PET/CT:

Three to five week old intact male athymic nu/nu T cell deficient mice and immunocompetent intact male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River. Nu/nu mice were inoculated with 1.5 × 106 H1975 cells subcutaneously into one flank in a 1:1 mixture (v/v) of media (RPMI) and Matrigel (Corning). Tumors were palpable within 8–14 days after injection. C57BL/6J mice were inoculated with 1.5× 106 B16F10 subcutaneously into one flank in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of Matrigel and DMEM. Tumors were palpable within 3–5 days after injection. Tumor bearing mice (n=4 per treatment arm) received between 40 to 250 μCi of solution in 100 μL saline solution volume intravenously using a custom mouse tail vein catheter with a 28-gauge needle and a 100–150 mm long polyethylene microtubing. ~200 μCi was injected for imaging studies and ~40 μCi for biodistribution. Carrier added studies were conducted by co-injecting atezo or the non-targeting IgG1 in the same syringe. The mice were imaged on a small animal PET/CT scanner (Inveon, Siemens Healthcare, Malvern, PA). Mice were imaged at multiple time points post injection out to 3 days. Animals were scanned for 20 minutes or until 20 million coincident events were collected for PET, and the CT acquisition was 10 minutes.

The co-registration between PET and CT images was obtained using the rigid transformation matrix from the manufacturer-provided scanner calibration procedure since the geometry between PET and CT remained constant for each of PET/CT scans using the combined PET/CT scanner. During the imaging procedure, animals were anesthetized with gas isoflurane at 2% concentration mixed with medical grade oxygen. The photon attenuation correction was performed for PET reconstruction using the co-registered CT-based attenuation map to ensure the quantitative accuracy of the reconstructed PET data.

Biodistribution studies:

Mice received ~40 μCi of radiotracer via tail vein injection for biodistribution studies. At 2, 4, 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours after radiotracer injection, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and blood and tissues were removed, weighed and counted on a gamma-counter for accumulation of 89Zr-radioactivity. The mass of 89Zr-antibody formulation injected into each animal was measured and used to determine the total number of counts per minute by comparison to a standard syringe of known activity and mass. The data were background- and decay-corrected and the tissue uptake was expressed in units of percentage injected dose per gram of dry tissue (%ID/g).

Statistical Analysis:

Data were analyzed using the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test using PRISM software. Differences at the 99% confidence level (P < 0.01) were considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge Dr. Youngho Seo and Sergio Wong of the Small Animal Imaging Core at UCSF for technical assistance, and Dr. Spencer Behr for helpful discussions. M.J.E. was supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation, an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant (130635-RSG-17–005-01-CCE), and the National Institute Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01EB025207). L.F. was supported by a Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Grant and the National Cancer Institute (R01CA223484). C.S.C. was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P41CA196276). Research from UCSF reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30CA082103. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Research from Singapore Immunology Network in this publication was supported by the Category 3 Industrial Alignment Fund (IAF 311007) awarded by the Biomedical Research Council of A*STAR.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available free of charge on the ACS publications website.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

- (1).Rizvi NA; Hellmann MD; Snyder A; Kvistborg P; Makarov V; Havel JJ; Lee W; Yuan J; Wong P; Ho TS; et al. (2015) Mutational Landscape Determines Sensitivity to PD-1 Blockade in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Science 348, 124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Patel SP; Kurzrock R (2015) PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Molecular cancer therapeutics 14, 847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Le DT; Durham JN; Smith KN; Wang H; Bartlett BR; Aulakh LK; Lu S; Kemberling H; Wilt C; Luber BS; et al. (2017) Mismatch Repair Deficiency Predicts Response of Solid Tumors to PD-1 Blockade. Science 357, 409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kwak JJ; Tirumani SH; Van den Abbeele AD; Koo PJ; Jacene HA (2015) Cancer Immunotherapy: Imaging Assessment of Novel Treatment Response Patterns and Immune-related Adverse Events. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc 35, 424–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wong ANM; McArthur GA; Hofman MS; Hicks RJ (2017) The Advantages and Challenges of Using FDG PET/CT for Response Assessment in Melanoma in the Era of Targeted Agents and Immunotherapy. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 44, 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wei W; Jiang D; Ehlerding EB; Luo Q; Cai W (2018) Non-invasive PET Imaging of T cells. Trends in cancer 4, 359–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ehlerding EB; England CG; McNeel DG; Cai W (2016) Molecular Imaging of Immunotherapy Targets in Cancer. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 57, 1487–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bensch F, van der Veen E, Jorritsma A, Lub-de Hooge M., Boellaard R, Oosting S, Schroder C, Hiltermann J, van der Wekken A, Groen H, et al. (2017) First in Human PET Imaging with the PD-L1 Antibody 89Zr-atezolizumab. Cancer research 77, Abtract nr CT017. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Donnelly DJ; Smith RA; Morin P; Lipovsek D; Gokemeijer J; Cohen D; Lafont V; Tran T; Cole EL; Wright M; et al. (2018) Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a Novel (18)F-labeled Adnectin as a PET Radioligand for Imaging PD-L1 Expression. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 59, 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bryan JN; Jia F; Mohsin H; Sivaguru G; Anderson CJ; Miller WH; Henry CJ; Lewis MR (2011) Monoclonal Antibodies for Copper-64 PET Dosimetry and Radioimmunotherapy. Cancer biology & therapy 11, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lesniak WG; Chatterjee S; Gabrielson M; Lisok A; Wharram B; Pomper MG; Nimmagadda S (2016) PD-L1 detection in Tumors Using [(64)Cu]Atezolizumab. Bioconjugate chemistry 27, 2103–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chatterjee S; Lesniak WG; Gabrielson M; Lisok A; Wharram B; Sysa-Shah P; Azad BB; Pomper MG; Nimmagadda S (2016) A Humanized Antibody for Imaging Immune Checkpoint Ligand PD-L1 Expression in Tumors. Oncotarget 7, 10215–10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sharma SK; Chow A; Monette S; Vivier D; Pourat J; Edwards KJ; Dilling TR; Abdel-Atti D; Zeglis BM; Poirier JT; et al. (2018) Anomalous Biodistribution of Therapeutic Antibodies in Immunodeficient Mouse Models. Cancer research 78, 1820–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Truillet C; Oh HLJ; Yeo SP; Lee CY; Huynh LT; Wei J; Parker MFL; Blakely C; Sevillano N; Wang YH; et al. (2018) Imaging PD-L1 Expression with ImmunoPET. Bioconjugate chemistry 29, 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Chatterjee S; Lesniak WG; Miller MS; Lisok A; Sikorska E; Wharram B; Kumar D; Gabrielson M; Pomper MG; Gabelli SB; et al. (2017) Rapid PD-L1 Detection in Tumors with PET Using a Highly Specific Peptide. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 483, 258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Herbst RS; Soria JC; Kowanetz M; Fine GD; Hamid O; Gordon MS; Sosman JA; McDermott DF; Powderly JD; Gettinger SN; et al. (2014) Predictive Correlates of Response to the Anit-PD-L1 Antibody MPDL3280A in Cancer Patients. Nature 515, 563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.