Abstract

Aims and objectives.

This systematic review describes studies evaluating screening tools and brief interventions for addressing unhealthy substance use in primary care patients with hypertension, diabetes or depression.

Background.

Primary care is the main entry point to the health care system for most patients with comorbid unhealthy substance use and chronic medical conditions. Although of great public health importance, systematic reviews of screening tools and brief interventions for unhealthy substance use in this population that are also feasible for use in primary care have not been conducted.

Design.

Systematic review.

Methods.

We systematically review the research literature on evidence-based tools for screening for unhealthy substance use in primary care patients with depression, diabetes and hypertension, and utilising brief interventions with this population.

Results.

Despite recommendations to screen for and intervene with unhealthy substance use in primary care patients with chronic medical conditions, the review found little indication of routine use of these practices. Limited evidence suggested the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-C screeners had adequate psychometric characteristics in patients with the selected chronic medical conditions. Screening scores indicating more severe alcohol use were associated with health-risk behaviours and poorer health outcomes, adding to the potential usefulness of screening for unhealthy alcohol use in this population.

Conclusions.

Studies support brief interventions’ effectiveness with patients treated for hypertension or depression who hazardously use alcohol or cannabis, for both substance use and chronic medical condition outcomes.

Relevance to clinical practice.

Although small, the international evidence base suggests that screening with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test or Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-C and brief interventions for primary care patients with chronic medical conditions, delivered by nurses or other providers, are effective for identifying unhealthy substance use and associated with healthy behaviours and improved outcomes. Lacking are studies screening for illicit drug use, and using single-item screening tools, which could be especially helpful for frontline primary care providers including nurses.

Keywords: alcohol, brief intervention, chronic medical conditions, depression, diabetes, drugs, hypertension, nursing, primary care, screening

Introduction

Unhealthy substance use, ranging from hazardous use to meeting diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder (SUD), is common among primary care (PC) patients. Up to 50% of PC patients in the USA report hazardous alcohol use, 18–44% have a current or lifetime alcohol use disorder, 35% report illicit substance use, and 13 and 47% have a current or lifetime drug use disorder, respectively (McQuade et al. 2000, Smith et al. 2010). Unhealthy substance use is associated with higher rates of chronic medical conditions (CMCs), including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2010), and plays a major role in their development and exacerbation. It is therefore important that PC nurses are prepared to address unhealthy substance use in this patient population.

Primary Care is the main entry to health care for most patients with comorbid substance use and CMCs, and is where both conditions are likely to be managed (Walley et al. 2012). Although of great public health importance due to the major and cumulative impact on individual patients, their families and their communities, identifying and managing substance use in PC patients with CMCs has received little attention (Cook & Cherpitel 2012). Drinkers diagnosed with CMCs who have irregular PC engage more in heavy drinking (Cook & Cherpitel 2012). Health care costs are higher for patients with both substance use and CMCs than for those with CMCs alone (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 2013). The high burden of chronic illness experienced by patients presenting to PC who use alcohol and illicit drugs highlights the need for using effective strategies to identify and address substance use in chronically ill patients.

Nurses are often the first contact for patients in the PC setting, and in this role conduct screenings for common health conditions. Nurses are also increasingly involved in the delivery of brief interventions (Broyles et al. 2012). Given the negative effects of unhealthy substance use among patients with CMCs, nurses should be familiar with the use of screening and brief intervention for addressing co-occurring substance use.

This systematic review addresses an important gap by reviewing studies that describe promising evidence-based strategies for identifying and addressing unhealthy substance use in patients with CMCs seen in PC. Given their role as “front line” providers in PC, it is important for nurses to be knowledgeable and prepared to incorporate evidence-based practices to improve care of PC patients with CMCs and unhealthy substance use. Substance use is potentially more dangerous among patients with CMCs than among those without these conditions. The demands of CMC management may override attention to unhealthy substance use during PC visits. Failure to recognise and address substance use may lead to adverse health events such as from illicit drug use by individuals with cardiovascular disease. That is, PC patients with SUDs in addition to CMCs may receive lower quality care. However, when PC nurses communicate more with their teams about patients’ hazardous substance use, patients use fewer health care resources (Mundt et al. 2015), suggesting improvements in overall health. Therefore, it is critical for PC nurses to be informed about screening and intervention strategies that can address this unhealthy substance use in persons with a CMC.

This review’s first aim was to describe screening tools that are feasible for use by busy PC providers, including their effectiveness in detecting unhealthy substance use, and their clinical utility as represented by associations between screening scores and health outcomes (e.g. treatment adherence) important in CMC management. In the second aim, we describe approaches to brief intervention and present evidence for their use in PC patients with unhealthy substance use and CMCs. As background, we first describe the role of substance use in these medical conditions.

Substances and CMCs

Compared to controls from the same health system, addiction patients had a greater prevalence of CMCs such as hypertension (Mertens et al. 2003). Among PC patients treated for opioid dependence, 74% reported at least one established CMC initially, and at least one newly identified CMC was subsequently found in 28% of patients (Rowe et al. 2012). Consistently, drug users in PC had higher rates of CMCs than nondrug users did (Palmer et al. 2012). SUDs were associated with higher odds of amputations and hospitaliszations due to diabetes (Leung et al. 2011).

Patients with SUDs have higher rates of CMCs, and patients with CMCs have higher rates of substance use, than do patients without these conditions. Higher rates of SUDs occurred among individuals reporting a history of CMCs such as high blood pressure, when compared to those reporting no CMCs (Wells et al. 1989). These findings highlight the increased medical needs of patients with SUDs and the potential role and importance of PC nurses in identifying and helping to manage substance use to improve patient outcomes.

Three pathways explain how substance use contributes to increased risk for developing CMCs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2011). First, substance use may be a causal factor in the development of a medical condition, e.g. cocaine-induced myocardial infarction. Second, substance use may exacerbate health conditions that developed separately, including diabetes, hypertension or depression. For diabetes, large amounts of acute or long-term alcohol consumption increase insulin resistance, triglyceride levels, blood pressure and all-cause mortality. For hypertension, reduced alcohol consumption is associated with reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Cook & Cherpitel 2012). Having a lifetime or current SUD may worsen the severity and increase the duration of depressive symptoms among individuals with depression (Boschloo et al. 2012).

In the third pathway, substance use may complicate the effective management of existing diabetes, hypertension and depression. Drinking is associated with poor illness control partly via poor adherence to dietary and physical activity recommendations and medications, and by adding to the complexity of treatment components needed to manage comorbid conditions such as depression (Gorka et al. 2012). Drinking has been shown to have a temporal and dose–response association with poor medication adherence among patients in treatment for hypertension, diabetes and depression. Even occasional drinking can reduce medication adherence (Cook & Cherpitel 2012). Drinking among persons with depression may also indicate a need for more intensive interventions that teach skills to reduce reliance on alcohol to cope (Gorka et al. 2012). Together, findings further emphasise the importance of identifying and treating substance use in these patient populations to improve management and long-term outcomes of these comorbid conditions.

Evidence-based approaches

Effective for addressing needs of people with unhealthy substance use is Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) – a public health approach to delivering early intervention and referral to treatment services. Screening identifies people with unhealthy use and, if accompanied by assessment of severity, also identifies possible goals, such as abstinence or reducing episodes of heavy consumption, to be considered in brief interventions.

Screening

Without screening, PC providers fail to recognise most patients with unhealthy substance use. A European study with 13,003 PC providers found little overlap between patients identified as alcohol dependent with validated screening tools or with provider judgment (Rhem et al. 2015). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the most studied instrument for screening for, and assessing the severity of, unhealthy alcohol use (US Preventive Services Task Force 2004), has high sensitivity and specificity and satisfactory AUC statistics in identifying at-risk or hazardous drinking, or alcohol use disorders, when compared across different gold standards and different countries. However, it may be too long for PC settings. The AUDIT’s first three questions, the AUDIT-C, were demonstrated to be an effective screening test for past-year hazardous drinking and active alcohol use disorders (Bradley et al. 2007); cut-off scores for unhealthy alcohol use are four drinks for men and three for women (Bradley et al. 2007), and for alcohol use disorders are five to six drinks for men and four for women (Dawson et al. 2005). A sole question (“How many times in the past year have you had X [five for men, four for women] or more drinks in a day?”) also accurately identifies unhealthy alcohol use in PC patients (Smith et al. 2010).

Other than for alcohol or tobacco, brief and psychometrically valid screening instruments are lacking. The Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 is frequently used to assess past-year drug consequences and problem severity, and has good psychometric characteristics (Yudko et al. 2007). Scores range from 0–10; ≥3 suggests unhealthy drug use. A sole item can accurately identify drug use in PC patients: “How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for nonmedical reasons?” (Smith et al. 2010); more than once indicates unhealthy drug use. The Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) is increasingly being used for assessing substance use and its consequences, but is probably too long to be feasible in busy PC settings (Saitz et al. 2010).

Brief interventions

Substance use assessment leads to either of two strategies, depending on patients having at-risk substance use or a SUD. Patients with at-risk use often receive brief interventions, referring to time-limited efforts to provide advice or information, boost motivation and self-efficacy to avoid substances, or teach skills to reduce use and associated problems through behaviour change. Brief interventions vary in length and content but typically involve 1–2 counselling sessions of ≤30 minutes apiece, and may include personalised feedback (age- and gender-matched normative comparisons of substance use and consequences). Brief motivational exchanges between nurses or other health professionals and patients are among the most time-efficient and cost-effective alcohol-related interventions (Cucciare et al. 2014). However, the literature documenting the effectiveness of brief interventions for illicit drug use is much smaller than for alcohol. For patients identified as having SUDs rather than risky use, brief interventions may be inadequate, and referrals to specialised treatments should be provided.

The most effective provider strategy for heavy drinking hypertensive patients is brief intervention (Miller et al. 2005): a 10-minute conversation about associations between unhealthy drinking and higher blood pressure, reduced effectiveness of antihypertensive medications and patient nonadherence to recommended behaviours (e.g. salt restriction). Emphasising alcohol–blood pressure connections avoids confrontational disagreements about having an “alcohol problem.” During brief intervention, nurses or physicians advise about lower limits of alcohol use or abstinence and consumption reduction strategies. During follow-ups, drinking goals are reviewed and progress reinforced. If consumption and blood pressure are both reduced, providers mention the link. However, if the patient maintains heavy drinking, providers should consider alcohol treatment referral.

Aims and methods

The goals of this study are to systematically review the research literature on use of evidence-based tools for screening for substance use in PC patients with CMCs, and conducting brief interventions with this patient population. Hypertension, diabetes and depression are exacerbated by substance use, commonly seen in PC (among the top five most common PC diagnoses), typically do not have a specialist as the primary provider, and have high associated morbidity and mortality (Cook & Cherpitel 2012). With regard to the first aim, we review feasible-to-use screening tools for detecting unhealthy substance use in the PC setting and describe their clinical utility (when data are available) in that setting with patients with the CMC. To achieve our second goal, we characterise the use of brief interventions for these specific patient groups and describe the findings of these studies. These goals address the extent to which evidence-based screening tools and brief interventions have been used with, and benefit, PC patients having hypertension, diabetes, or depression, describe the prevalence of substance use in patients with these CMCs, and brief strategies that can be used by PC nurses for managing unhealthy substance use in patients with these conditions.

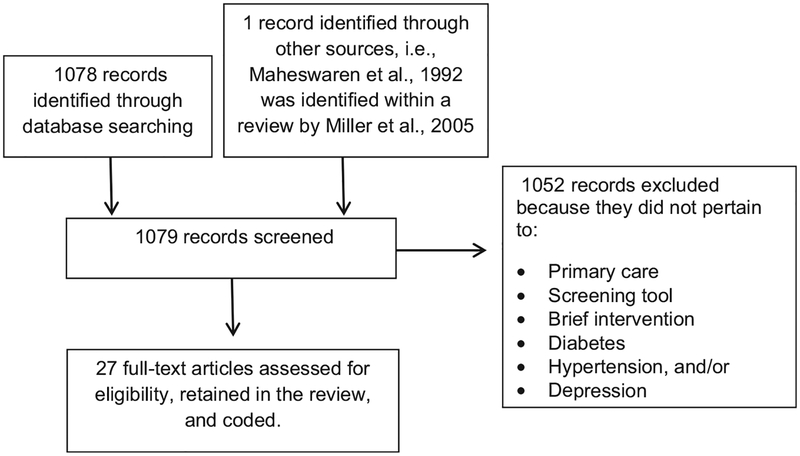

We conducted searches (through September 30, 2015) of the published literature in PubMed using the 36 terms listed in Table 1. The first three searches were “Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test hypertension,” followed by replacing “hypertension” with “diabetes” and then “depression.” The next three searches were AUDIT-C hypertension, AUDIT-C diabetes and AUDIT-C depression. The remaining searches followed the sequence of terms listed in Table 1. Searches replacing “intervention” with “counselling” or “advice” yielded a subset of the same studies and so they were dropped. Searches were limited to articles in English, but not limited as to publication year. Study retention criteria were that the article provided primary data and analyses pertaining to PC, to the screening tool or brief intervention included in the search term, and to the CMC included in the search term (Fig. 1). Narrative reviews were used to identify relevant articles that were not identified in the PubMed searches. Data collected from each retained study included its country of origin, design (using the quality hierarchy of randomised trial > quasi-experimental > prospective cohort > retrospective cohort), its other information (such as psychometric information on the screening tool, prevalence of alcohol or drug use, or content and outcomes of the brief intervention), and a summary of key additional findings. Each identified study was reviewed by one author and one research assistant to determine whether it should be retained, and if so, to code its data.

Table 1.

Literature searches on alcohol and drug screening instruments and brief interventions with primary care patients having chronic medical conditions: Numbers of studies identified and retained Ident, Identified; Ret, Retained.

| Hypertension | Diabetes | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ident | Ret | Ident | Ret | Ident | Ret | |

| Screening search term | ||||||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test | 30 | 1 | 30 | 2 | 226 | 3 |

| AUDIT-C | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 39 | 1 |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test | 11 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 130 | 0 |

| Single screening question alcohol | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Single screening question drugs | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Single screening question drug | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Single-item alcohol screening | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Single-item drugs screening | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| Single-item drug screening | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Brief intervention search term | ||||||

| Brief intervention alcohol | 19 | 5 | 21 | 3 | 126 | 6 |

| Brief intervention drugs | 6 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 55 | 0 |

| Brief intervention drug | 16 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 177 | 0 |

Figure 1.

Article selection process. (Adapted from “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.”)

Results

Screening

Table 1 shows results of literature searches to identify studies. Table 2 describes studies retained from these searches.

Table 2.

Studies retained from literature searches

| Authors, country, design | Aims |

|---|---|

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test hypertension | |

| Kim et al. (2012) | Examine alcohol consumption in men with hypertension in South Korea |

| Korea | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| AUDIT-C hypertension | |

| Bryson et al. (2008) | Identify whether alcohol misuse is associated with medication nonadherence in veterans attending primary care |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Rittmueller et al. (2015) | Examine alcohol consumption in male veterans with hypertension |

| USA | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test diabetes | |

| Leonardson et al. (2005) | Give the AUDIT to 50 Northern Plains American Indians with diabetes to assess its reliability and validity |

| USA | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| Johnson et al. (2000) | Examine associations of alcohol consumption with self-reported compliance with recommended health behaviours for diabetes |

| USA | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| AUDIT-C diabetes | |

| Bryson et al. (2008) | Identify whether alcohol misuse is associated with medication nonadherence in veterans attending primary care |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Thomas et al. (2012) | Examine alcohol misuse’s association with diabetes self-care |

| USA | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test depression | |

| Boschloo et al. (2010) | Examine AUDIT-C performance in detecting alcohol dependence and abuse in depressed or anxious individuals |

| Netherlands | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| van den Berg et al. (2014) | Identify correlates of at risk drinking in a sample of depressed and nondepressed older adults |

| Netherlands | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| Shippee et al. (2014) | Determine prevalence of hazardous drinking in depressed patients; and association of drinking with remission |

| USA | |

| Prospective cohort | |

| AUDIT-C depression | |

| Ahlin et al. (2015) | Compare AUDIT-C scores of depressed patients to general population |

| Sweden | |

| Retrospective cohort | |

| Brief intervention alcohol hypertension | |

| Maheswaran et al. (1992) | Evaluate the effectiveness of advice to reduce alcohol to manage hypertensive patients |

| UK | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Fleming et al. (2004) | Examine brief intervention to identify and intervene with patients with chronic medical problems affected by heavy drinking |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Rose et al. (2008) | Determine effect of intervention to improve alcohol screening and brief counselling for hypertensive patients in primary care |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Gannon et al. (2011) | Evaluate web-based programme for physicians to assess and manage at-risk alcohol use in patients with hypertension |

| USA | |

| Prospective cohort | |

| Ornstein et al. (2013) | Report impact of dissemination of practice-based quality improvement approach on alcohol screening and brief intervention for at-risk drinking and alcohol use disorders in primary care |

| USA | |

| Group randomised trial | |

| Wilson et al. (2014) | Evaluate the effectiveness of advice to reduce excessive drinking in primary care patients with hypertension |

| England | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Brief intervention alcohol diabetes | |

| Fleming et al. (2004) | Examine brief intervention to identify and intervene with patients with chronic medical problems affected by heavy drinking |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Ramsey et al. (2010) | Examine whether brief intervention reduces alcohol consumption among patients with diabetes who are at-risk drinkers |

| USA | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Ornstein et al. (2013) | Report impact of dissemination of practice-based quality improvement approach on alcohol screening and brief intervention for at-risk drinking and alcohol use disorders in primary care |

| USA | |

| Group randomised trial | |

| Brief intervention drugs diabetes | |

| Ornstein et al. (2013) | Report impact of dissemination of practice-based quality improvement approach on alcohol screening and brief intervention for at-risk drinking and alcohol use disorders in primary care |

| USA | |

| Group randomised trial | |

| Brief intervention alcohol depression | |

| Kay-Lambkin et al. (2009) | Compare a computer-based v. therapist-based intervention for persons with comorbid depression and substance use. |

| Australia | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Wilton et al. (2009) | Test the efficacy of brief intervention for alcohol use on depression symptoms among postpartum women |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Grothues et al. (2008) | Examine the differential effectiveness of brief intervention for alcohol misuse on a sample of depressed (and nondepressed) patients with comorbid alcohol misuse |

| Germany | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Kay-Lambkin et al. (2011) | Examine the relative acceptability of a computerised intervention, therapist-delivered intervention, and brief intervention for comorbid alcohol and depression |

| Australia | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Montag et al. (2015) | Evaluate effectiveness of Internet-based intervention on alcohol consumption and depression in American Indian/Alaska Native women |

| USA | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

| Wilson et al. (2014) | Evaluate the effectiveness of advice to reduce excessive drinking in primary care patients with mild-to-moderate depression |

| England | |

| Randomised controlled trial | |

Hypertension

For the search Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test hypertension, the retained study (Kim et al. 2012), examined past-year alcohol consumption in 490 South Korean men with physician-diagnosed hypertension (AUDIT’s alpha = 0 87). Using recommended cut-off scores for Koreans (Kim et al. 2012), 11% were “problem drinkers,” 24% had an alcohol use disorder and 3% were alcohol dependent. These “hazardous drinkers” were more likely than nonhazardous drinkers to report smoking and high stress levels. Only 1 4% were advised about alcohol consumption during treatment.

For AUDIT-C hypertension, the retained study (Bryson et al. 2008) investigated 13,729 PC patients (mainly men) taking antihypertensive medications, classifying them as past-year nondrinkers (47 4%, AUDIT-C score = 0), and low-level (30 2%, 1–3), mild (11 1%, 4–5), moderate (5 5%, 6–7), and severe (5 8%, 8–12) alcohol users. For 90 days and one year, higher AUDIT-C categories were associated with decreased medication adherence, supporting the AUDIT-C’s clinical utility. Similarly, male outpatients with self-reported hypertension (n = 11,927) were divided into nondrinking (46 8%), and low-level (31 0%), mild (11 3%), moderate (5 3%), and severe (5 4%) alcohol users based on AUDIT-C scores (0, 1–3, 4–5, 6–7, and 8–12, respectively) (Rittmueller et al. 2015). Increasing consumption was associated with less salt avoidance, exercise, weight control, not smoking and the combination of the four behaviours.

Diabetes

In searching Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test diabetes, one study retained considered 50 Indian Health Service patients (58% women) diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (AUDIT’s alpha = 0 97). Higher scores were associated with more depression symptoms and family dysfunction, and less well-being (Leonardson et al. 2005). A study of 392 PC patients (64% women) with type 2 diabetes identified past-year “problem drinking” (≥6 on the AUDIT, >14 drinks/week, or binge drank) in 9% (Johnson et al. 2000). Compared to nondrinking patients (81%), patients who drank were less compliant with dietary, exercise and medication recommendations.

For AUDIT-C diabetes, Bryson et al. (2008) also examined 3,468 patients taking oral hypoglycaemic agents: 56 7% nondrinkers, and 29 9% low-level, 6 9% mild, 3 1% moderate and 3 3% severe alcohol users. AUDIT-C scores were not associated with medication adherence. Thomas et al. (2012) divided male outpatients (n = 3930) with diabetes into the same groups based on the AUDIT-C: no past-year alcohol use (56 5%, 0), and low-level (30 4%, 1–3), mild (7 1%, 4–5), moderate (2 8%, 6–7) and severe (3 1%, 8–12) use. Higher AUDIT-C scores and poorer diabetes self-care were positively associated.

Depression

For the search Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test depression, one study revealed that the AUDIT is relatively accurate for identifying alcohol dependence in depressed men (AUC = 0 89; AUDIT score ≥9) and women (AUC = 0 88; AUDIT score ≥6), but less so for identifying alcohol abuse in depressed men (AUC = 0 74) and women (AUC = 0 78) (Boschloo et al. 2010). AUDIT-C cut-off scores with satisfactory sensitivity and specificity could not be determined for alcohol abuse detection (Boschloo et al. 2010). When the AUDIT was used to classify depressed, older PC patients as abstaining from alcohol use (40%; 0) or engaging in “moderate” (40 8%; 1–4) or “at-risk” (19%; ≥5) drinking, at-risk drinkers were more likely than moderate drinkers to smoke and report distress (van den Berg et al. 2014). Shippee et al. (2014) determined that 5 3% (n = 80) of 1,507 depressed adults in PC drank hazardously (scored ≥8 on the AUDIT), and that hazardous drinking predicted a marginally lower likelihood of depression remission at 6-month follow-up.

For the search AUDIT-C depression, a study of 946 PC patients diagnosed with mild-to-moderate depression found higher AUDIT-C scores in this population than in the general adult population (Ahlin et al. 2015). However, this difference was significant only for men, and was stronger for older patients.

Brief intervention

Hypertension

For the search brief intervention alcohol hypertension, Maheswaran et al. (1992) followed hypertensive patients receiving either brief advice or no advice for 18 months. The advice group was asked to reduce alcohol consumption in a manner tailored to their drinking behaviour, and educated on potential consequences of risky use and benefits of reducing consumption (e.g. control blood pressure). Advice was delivered in 10–15 minutes in an unhurried manner to optimise its suitability for PC. Alcohol consumption, GGT, and diastolic blood pressure decreased more in the advice group. Fleming et al. (2004) compared usual care and brief intervention (two 15-minute sessions with a nurse or physician assistant, including results of an alcohol biomarker test, plus two 5-minute phone calls from a nurse) to reduce drinking among patients with hypertension and/or type 2 diabetes. More intervention than control participants reduced heavy drinking and had improved biomarker results at one-year follow-up.

Some studies took a provider rather than patient focused approach to facilitating brief interventions. A web-based programme educated 17 PC physicians to screen for alcohol use and use brief interventions for at-risk drinking with patients with hypertension, depression or sleep difficulties (Gannon et al. 2011). Screening rates increased between baseline and 3-month follow-up for new and established patients. However, brief intervention rates did not change, possibly because physicians preferred referring patients screening positive to specialty care.

A two-year intervention designed to improve rates of alcohol screening and brief intervention for hypertensive PC patients was studied in 21 clinics with a common medical record (Rose et al. 2008). The intervention consisted of site visits from study staff members, and invitations to participate in meetings with colleagues to review project progress and disseminate improvement strategies. Intervention clinics were more likely than controls to be screening hypertensive patients after two years, and to have patients identified as engaging in high-risk drinking or diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder receiving brief intervention. Blood pressure also decreased among patients with hypertension receiving alcohol counselling.

Another study disseminated a practice-based quality improvement approach to alcohol screening and brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in PC (Ornstein et al. 2013). Nineteen practices acting for 26,005 patients with hypertension and/or diabetes participated in early or delayed intervention. The one-year intervention was composed of site visits, participatory planning, and meetings with colleagues to disseminate best practices. At Phase 1’s completion, patients in the early-intervention practices, compared to patients in the delayed-intervention practices, were more likely to have been screened and provided brief intervention. At Phase 2’s end, patients in delayed-intervention practices were more likely than at the completion of Phase 1 to have been screened and provided brief intervention. The performance of screening and brief intervention was maintained in the early-intervention practices during Phase 2.

Wilson et al. (2014), after screening 33,813 general practice patients, determined that 5 1% (n = 1709) had both hypertension and hazardous drinking (scored ≥7 on the AUDIT). A subset of these were randomised to receive brief structured alcohol advice of five minutes, tailored to the patient’s hypertension comorbidity, and an information brochure (intervention) or the information brochure alone (control), with follow-up six months later. Statistical significance was not reported, but, at follow-up, 36% of intervention patients, compared to 26% of control patients, had AUDIT scores below the cut-off for hazardous drinking. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure also improved more among intervention patients.

Diabetes

For brief intervention alcohol diabetes, three studies were retained, two of which have been discussed (Fleming et al. 2004, Ornstein et al. 2013). The third study assigned patients with type 1 or 2 diabetes who screened positive for risky drinking to brief intervention (one 50-minute session with a psychologist using Motivational Interviewing) or standard care (Ramsey et al. 2010). The brief intervention group showed greater declines in alcohol consumption, drinking frequency, and percentage of heavy drinking days at six-month follow-up. Reduced alcohol consumption was also associated with more diabetes self-care.

Depression

Within brief intervention alcohol depression, Kay-Lambkin et al. (2009) studied comorbid unhealthy alcohol and/or cannabis use and depression in PC and mental health settings. All participants received a single-session, in-person brief intervention consisting of assessment and feedback, goal setting, brief advice, and case formulation, and were then randomised to receive no further treatment or a nine-session intervention based on motivational interviewing (MI) and cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) given via provider or computer. In all conditions, participants significantly reduced depressive symptoms and cannabis and alcohol use over time. Individuals in the CBT/MI conditions showed more improvement in depressive symptoms and cannabis use when compared to brief intervention alone. However, the single-session brief intervention was as effective as the lengthier CBT/MI interventions for reducing alcohol consumption. Subsequently, Kay-Lambkin et al. (2011) examined the acceptability of brief intervention alone relative to brief intervention plus more intensive CBT/MI interventions for treating comorbid depression and substance use. Participant ratings of treatment acceptability did not differ among the three modalities.

Wilton et al. (2009) assigned drinking mothers with postpartum depression (recruited from obstetricians) to usual care or brief intervention consisting of two provider-delivered, 15–30 minute sessions with CBT/MI components. Participants in both conditions reduced drinking, with greater reductions in brief intervention (Fleming et al. 2004). However, only participants in brief intervention reduced depression from baseline to six-month follow-up. Grothues et al. (2008) assigned drinking patients with and without comorbid depression to control or brief intervention. Brief intervention was associated with reduced drinking among noncomorbid but not comorbid participants.

Montag et al. (2015) found different results in a sample of 234 American Indian/Alaska Native women randomly assigned to assessment of alcohol use plus intervention (web-based, personalised feedback about alcohol consumption) or assessment alone. Both groups reduced drinking, but of those in the brief intervention group, depressed women decreased drinking more than nondepressed women. Depressed women started the study at baseline consuming more drinks weekly and having more episodes of binging.

In Wilson et al.’s (2014) screening, 2 7% of patients had low mood or mild or moderate depression and also drank hazardously. In a pilot study, among control patients, 8 3% had AUDIT scores at six-month follow-up under the cut-off for hazardous drinking, but none of the participants in the brief intervention condition (five minutes of advice, tailored to depression) scored below the cut-off. However, 33% of control patients, compared to 43% of intervention patients, scored below the cut-off for depression.

Discussion

Despite widespread recommendations to screen for and intervene with substance use among PC patients with CMCs, the small number of studies identified in this systematic review provides little indication that these practices are being used routinely. Regarding screening, the limited data available suggest that the AUDIT and AUDIT-C have adequate psychometric characteristics in PC patients with hypertension (Bryson et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2012), diabetes (Leonardson et al. 2005), and depression (alcohol dependence, but not abuse) (Boschloo et al. 2010). However, more prospective studies are needed to bolster findings that screening tools meet sensitivity, specificity, and AUC criteria in these patient groups.

Studies that used the AUDIT and AUDIT-C revealed that roughly 10% of patients with hypertension and/or diabetes also screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use (Leonardson et al. 2005, Bryson et al. 2008, Thomas et al. 2012), but the prevalence among depressed patients is likely higher (van den Berg et al. 2014). Studies in the present review were of patients already in routine PC who may have had opportunities to receive intervention, thereby potentially reducing their alcohol use. Rates of unhealthy alcohol use may be even higher in patients new to care (Rowe et al. 2012), pointing to the importance for PC nurses to include screeners for substance use during a patient’s initial visit.

Supporting clinical utility of the screening tools, more severe alcohol use was associated with a variety of health-risk behaviours in patients with CMCs, including decreased self-monitoring, medication, smoking, dietary and exercise adherence, and increased mental health and family problems. One study identified associations of higher AUDIT-C scores with poorer health indices (Thomas et al. 2012). Together, these data suggest that the AUDIT-C and AUDIT adequately detect unhealthy alcohol use in patients with CMCs. That scores on these screeners are also associated with other important health outcomes in this population potentially enhances their usefulness in the management of comorbid CMCs.

The review did not identify any studies involving screening for illicit drug use in PC patients with the selected CMCs, despite knowledge that opiate and marijuana misuse is particularly common in this setting (Smith et al. 2010). Knowledge of illicit drug use is essential to avoid medication interactions. In addition, there were no identified studies of single-item screeners, which are especially helpful within the time constraints imposed by PC. On shortness, scoring ease, and validity for detecting the range of drug use of concern in PC, the single-item screen has favourable characteristics for use in this setting (Smith et al. 2010).

Studies in this review were conducted mainly in the USA but also in other countries. Although PC is designed to address the majority of health care needs, the extent to which alcohol and drug use is screened for and addressed within PC varies by country. Korean PC services are seen as under-performing because they are often bypassed by patients going directly to hospitals for services; alcohol screening and brief intervention are rarely implemented in PC (World Health Organization [WHO] 2010). In contrast, Dutch PC draws international positive attention because of its high performance at low cost. Regional practice groups offer disease management programmes, including for patients with multiple chronic conditions; nevertheless, implementation of alcohol screening and brief intervention in PC is atypical (WHO 2010). Health care reform in the USA, Germany, England and Australia has strengthened chronic disease management in PC, and coordination with specialty care, such as addiction services. Specifically, PC screening and brief intervention for hazardous drinking takes place in the USA and England, but infrequently in Germany or Sweden (Drummond et al. 2013).

Limitations

Literature was not reviewed pertaining to the Referral to Treatment component of SBIRT. Still needed is a systematic review of the literature on referrals from primary to specialty care among patients with CMCs using alcohol and drugs more severely. Another limitation was the use of restricted numbers of CMCs and search terms. Finally, although SUDCMC patients are seen in medical settings other than PC, the literature review did not include such settings.

Conclusion

Available evidence suggests that screening with the AUDIT or AUDIT-C and brief interventions for PC patients with CMCs are effective for identifying unhealthy substance use and associated with healthy behaviours and improved outcomes. However, the evidence base for use with patients with these comorbidities is small. A larger evidence base should facilitate implementation by the international nursing community of the use of evidence-based tools for identifying and managing substance use in patients with CMCs, and thus lower the costs of providing optimal care for these patients.

Relevance to clinical practice

The studies reviewed generally support the efficacy of brief interventions with patients treated for hypertension, diabetes or depression who use alcohol (or cannabis for depressed individuals) in terms of both reducing substance use and improving CMC outcomes (Maheswaran et al. 1992, Rose et al. 2008, Kay-Lambkin et al. 2009). These data, collected mainly in studies with high-quality RCT designs, suggest that routine use of brief interventions within PC to treat comorbid substance use among patients with CMCs may lead to improved outcomes. Brief interventions for alcohol use are well-suited to busy PC settings because they are time-limited (1–2 sessions), flexible in approach (motivational, educational) and effectively delivered by a range of providers including nurses. Nurses are particularly well-suited to deliver brief interventions, because they often serve as frontline providers who are responsible for the screening of health conditions and so are able to respond quickly to a positive screen. However, competing priorities and care mandates challenge the delivery of brief interventions by PC nurses. Delivery of brief interventions needs to be supported by clinic leadership and identified as high priority. Perhaps feasible for widespread implementation and also effective, are Internet-based substance use screeners and brief interventions to better care for PC patients with CMCs. Such tools can increase disclosure of substance use and access to evidence-based care by providing confidential and person-alised interventions to large numbers of patients at low cost (Cucciare et al. 2014).

Although training providers is effective in promoting the use of screening and brief interventions with alcohol use among PC patients with hypertension (Ornstein et al. 2013), additional barriers to utilising these practices have been uncovered. These include time and privacy constraints, limited interdisciplinary collaboration around substance-related care, patients’ defensiveness about questions concerning alcohol, and stigma linked to SUD diagnoses (Miller et al. 2005). The lack of use of screening and brief interventions occurs partly because health care providers perceive themselves as lacking substance-related knowledge and skills. In a large study on how PC providers address SUDs, <20% were self-described as very prepared to identify these problems, and >50% of patients said their PC providers did nothing to address these problems (Altman 2012). Continued efforts are needed to identify practical methods to overcome these barriers in ways that are adapt able to different clinics. Adaptations will need to consider how PC works within the clinic’s national health care system, such as whether most patients with unhealthy substance use are seen in the PC or specialty sector, and whether patients have direct access to SUD specialists or require prior referral by a PC provider.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Although primary care is where most patients with comorbid chronic medical conditions and unhealthy substance use are managed, alcohol and drug screening and intervention by nurses need more attention in routine practice.

This systematic review found that, although small, the international evidence base suggests that screening and brief interventions for primary care patients with chronic medical conditions are effective for identifying at-risk substance use and are associated with healthy behaviours and improved outcomes.

Still lacking are studies of screening for illicit drug use, and using single-item screening tools, which may be especially helpful for primary care nursing.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Timko and Dr. Cucciare were supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Research and Development (Health Services Research &Development Service, RCS 00–001, and CRE 12–009 respectively).

References

- Ahlin J, Hallgren M, Ojehagen A, Kallmen H & Forsell Y (2015) Adults with mild to moderate depression exhibit more alcohol related problems compared to the general adult population. BioMed Central Public Health 15, 542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DE (2012) Addiction Medicine: Closing the Gap between Science and Practice. Columbia University, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2010) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg JF, Kok RM, van Marwijk HWJ, van der Mast RC, Naarding P, Voshaar RCO, Stek MI, Verhaak PFM, de Waal MWM & Comijs HC (2014) Correlates of alcohol abstinence and at-risk alcohol consumption in older adults with depression: the NESDO study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 22, 866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, Smit JH, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ, Beekman AT & Penninx BW (2010) The performance of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in detect ing alcohol abuse and dependence in a population of depressed or anxious persons. Journal of Affective Disorders 126, 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, Smit JH, Veltman DJ, Beekman AT & Penninx BW (2012) Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 200, 476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D & Kivlahan DR (2007) AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 31, 1208–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles LM, Rosenberg E, Hanusa BH, Kraemer KL & Gordon AJ (2012) Hospitalized patients’ acceptability of nurse-delivered screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 36, 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR & Bradley KA (2008) Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Annals of Internal Medicine 149, 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WK & Cherpitel CJ (2012) Access to health care and heavy drinking in patients with diabetes or hypertension. Substance Use and Misuse 47, 726–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Coleman E & Timko C (2014) A conceptual model to facilitate transitions from primary care to specialty substance use disorder care. Primary Health Care Research and Development 12, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS & Zhou Y (2005) Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk of drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 29, 844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond C, Wolstenholme A, Deluca P, Davey Z, Donoghue K, Elzerbi C, Gual A, Robles N, Goos C, Strizek J, Godfrey C, Mann K, Zois E, Hoffman S, Gmel G, Kuendig H, Scafato E, Gandin C, Reynolds J, Segura L, Colom J, Baena B, Coulton S & Kaner E (2013) Alcohol Interventions and treatments in Europe In Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA (Anderson P, Braddick F, Reynolds J & Gual A eds). The AMPHORA Project, Catalonia, pp. 72–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming M, Brown R & Brown D (2004) The efficacy of a brief intervention combined with % CDT feedback in patients being treated for type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 65, 631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon MA, Qaseem A, Snow V & Turner B (2011) Raising achievement: educating physicians to address effects of at-risk drinking on common diseases. Quality in Primary Care 19, 43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Aliu B & Daughters SB (2012) The role of distress tolerance in the relationship between depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 26, 621–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothues JM, Bischof G, Reinhardt S, Meyer C, John U & Rumpf HJ (2008) Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions for general practice patients with problematic drinking behavior and comorbid anxiety and depression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 94, 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KH, Bazargan M & Bing EG (2000) Alcohol consumption and compliance among inner-city minority patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Archives of Family Medicine 9, 964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ & Carr VJ (2009) Computer-based psychological treatment for comorbid depression and problematic alcohol and/or cannabis use. Addiction 104, 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker A, Lewin T & Carr V (2011) Acceptability of a clinician-assisted computerized psychological intervention for comorbid mental health and substance use problems. Journal of Medical Internet Research 13, e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim O, Kim BH & Jeon HO (2012) Risk factors related to hazardous alcohol consumption among Korean men with hypertension. Nursing and Health Sciences 14, 204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardson GR, Kemper E, Ness FK, Koplin BA, Daniels MC & Leonard-son GA (2005) Validity and reliability of the audit and CAGE-AID in Northern Plains American Indians. Psychological Reports 97, 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung G, Zhang J, Lin WC & Clark RE (2011) Behavioral disorders and dia betes-related outcomes among Massachusetts Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Psychiatric Services 62, 659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheswaran R, Beevers M & Beevers DG (1992) Effectiveness of advice to reduce alcohol consumption in hyper-tensive patients. Hypertension 19, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuade WH, Levy SM, Yanek LR, Davis SW & Liepman MR (2000) Detecting symptoms of alcohol abuse in primary care settings. Archives of Family Medicine 9, 814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Lu YW, Parthasarathy S, Moore C & Weisner CM (2003) Medical and psychiatric conditions of alcohol and drug treatment patients in HMO: comparison with matched controls. Archives of Internal Medicine 163, 2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, Anton RF, Egan BM, Basile J & Nguyen SA (2005) Excessive alcohol consumption and hypertension. Journal of Clinical Hypertension 7, 346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag AC, Brodine SK, Alcaraz JE, Clapp JD, Allison MA, Calac DJ, Hull AD, Gorman JR, Jones KL & Chambers CD (2015) Effect of depression on risky drinking and response to a screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment intervention. American Journal of Public Health 105, 1572–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI, Shoham DA, Tuan WJ & Carayon P (2015) Together achieving more: primary care team communication and alcohol-related healthcare utilization and costs. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 39, 2003–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein SM, Miller PM, Wessell AM, Jenkins RG, Nemeth LS & Nietert PJ (2013) Integration and sustainability of alcohol screening, brief intervention, and pharmacotherapy in primary care settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 74, 598–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer F, Jaffray M, Moffat MA, Matheson C, McLernon DJ, Coutts A & Haughney J (2012) Prevalence of common chronic respiratory diseases in drug misusers: a cohort study. Primary Care Respiratory Journal 21, 377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA Transparent Reporting of Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis (2015).Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). Retrieved from http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed 22 February 2015)

- Ramsey SE, Engler PA, Harrington M,Smith RJ, Fagan MJ, Stein MD & Friedmann P (2010) Brief alcohol intervention among at-risk drinkers with diabetes. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment 4, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhem J, Allamani A, Vedova RD, Elekes Z, Jakubczyk A, Landsmane I, Man-they J, Moreno-Espana J, Pieper L, Probst C, Snikere S, Struzzo P, Voller F, Wittchen HU, Gual A & Wojnar M (2015) General practitioners recognizing alcohol dependence: a large cross-sectional study in 6 European countries. Annals of Family Medicine 13, 28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmueller SE, Frey MS, Williams EC, Sun H, Bryson CL & Bradley KA (2015) Association between alcohol use and cardiovascular self-care behaviors among male hypertensive Veterans Affairs outpatients. Substance Abuse 36, 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2013) Super-Utilizer Summit: Common Themes from Innovative Complex Care Management Programs. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Rose HL, Miller PM, Nemeth LS, Jenkins RG, Nietert PJ, Wessell AM & Ornstein S (2008) Alcohol screening and brief counseling in a primary care hypertensive population: a quality improvement intervention. Addiction 103, 1271–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe TA, Jacapraro JS & Rastegar DA (2012) Entry into primary care-based buprenorphine treatment is associated with identification and treatment of other chronic medical problems. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice 7, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Alford DP, Bernstein J, Cheng D, Samet J & Palfai T (2010) Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: randomized clinical trials are needed. Journal of Addiction Medicine 4, 123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee ND, Rosen BH, Angstam KB, Fuentes ME, DeJesus RS, Bruce SM & Williams MD (2014) Baseline screen ing tools as indicators for symptom outcomes and health services utilization in a collaborative care model for depression in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 36, 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D & Saitz R (2010) A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Archives of Internal Medicine 170, 1155–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2011) Managing Chronic Pain in Adults With or in Recovery from Substance Use Disorders Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 54. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12–4671. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RM, Francis Gerstel PA, Williams EC, Sun H, Bryson CL, Au DH & Bradley KA (2012) Association between alcohol screening scores and diabetic self-care behaviors. Family Medicine 44, 555–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force (2004) Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse. Annals of Internal Medicine 140, 554–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Tetrault JM & Friedmann PD (2012) Integration of substance use treatment and medical care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 43, 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Golding JM & Burnam AM (1989) Affective, substance use, and anxiety disorders in persons with arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, or chronic lung conditions. General Hospital Psychiatry 11, 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GB, Wray C, McGovern R, Newbury-Birch D, McColl E, Crosland A, Speed C, Cassidy P, Tomson D, Haining S, Howel D & Kaner EFS (2014) Intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption and improve comorbid outcomes in hypertensive or depressed primary care patients. Trials 14, 235–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton G, Moberg DP & Fleming MF (2009) The effect of brief alcohol intervention on postpartum depression. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing 34, 297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010) ATLAS of Substance Use Disorders: Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders (SUD). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O & Fouts A (2007) A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 32, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]