Abstract

Objective:

Determine whether weight losses from a primarily smartphone-based behavioral obesity treatment differed from those of a more intensive group-based approach and a control condition.

Methods:

276 adults with overweight/obesity were randomized to 18-months of: GROUP-based treatment with meetings weekly for 6 months, bi-weekly for 6 months, and monthly for 6-months and self-monitoring via paper diaries with written feedback; SMARTphone-based treatment with online lessons, self-monitoring, and feedback and monthly weigh-ins; or a CONTROL condition with self-monitoring via paper diaries with written feedback and monthly weigh-ins.

Results:

Among the 276 participants (17% men; 7.2% minority; mean [SD] age, 55.1 [9.9] years; weight, 95.9 [17.0] kg; BMI, 35.2 [5.0] kg/m2), 18-month retention was significantly higher in both GROUP (83%) and SMART (81%) compared to CONTROL (66%). Estimated mean (95% CI) weight change over 18 months did not differ across the three conditions; 5.9 kg (95% CI, 4.5 to 7.4) in GROUP, 5.5 kg (95% CI, 3.9 to 7.0) in SMART, and 6.4 kg (95% CI, 3.7 to 9.2) in CONTROL.

Conclusions:

Mobile online delivery of behavioral obesity treatment can achieve weight loss outcomes that are at least as good as those obtained via the more intensive gold standard group-based approach.

Keywords: behavioral, treatment, online, eHealth, mHealth

INTRODUCTION

Behavioral obesity treatments focused on improving eating, physical activity (PA), and related behaviors reliably produce mean weight losses of 5–10% of initial body weight.1 These weight losses reduce risk and severity of multiple diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer.2–4 However, these treatments are not widely available because they are highly intensive, typically involving weekly individual and/or group treatment sessions, often for several months.4 Thus, costs to both providers and patients can be high due to the need for specially trained staff to lead treatment sessions, and the potential need for patients to take time off work, arrange childcare, etc.5,6

Innovative approaches are needed to make behavioral obesity treatment more accessible and less costly. A variety of online and mobile technologies have been tested for the delivery of behavioral obesity treatment, on their own or in combination with other modalities (e.g., in combination with clinic visits and/or phone calls).7–9 Reviews shows that these interventions typically produce superior weight loss compared to control conditions involving little or no intervention.7–9 Although mobile and online interventions appear to produce weight losses smaller than the 5–10% of initial body weight typically obtained via gold-standard treatment delivered in-person, we are aware of only one 2010 study by Harvey-Berino et al. that has directly compared the weight losses obtained via in-person versus online treatment.10 At the 6-month primary endpoint, Internet-based treatment produced significant mean (SD) weight loss of 5.5 (5.6) kg, but less than the 8.0 (6.1) kg of in-person treatment. Taken together, the previous research suggests an ongoing need for work aimed at developing and testing online and mobile interventions that can produce weight losses that are at least as good as those achieved via gold-standard in-person treatment.

A mobile health (mHealth) approach has potential to fill the need by combining the Internet with mobile devices such as smartphones to deliver behavioral treatment with fewer clinic visits.5 Furthermore, self-monitoring of weight, dietary intake, and PA is one of the most important components of behavioral obesity treatments,11,12 and mHealth approaches may be especially suited to capitalize on well-developed commercial tools for self-monitoring that are available at no cost.13 The Self-Monitoring and Recording Using Technology (SMART) Trial conducted by Burke et al. showed that, compared to paper diaries, use of electronic tools for tracking diet and providing feedback produced the best adherence to self-monitoring and weight loss outcomes at 24-months, although this study involved in-person treatment.14

The primary aim of this randomized clinical trial was to test whether a primarily smartphone-based behavioral obesity treatment with electronic self-monitoring and feedback, and monthly clinic weigh-ins, would produce mean weight losses at 18months that were at least as good as the more intensive gold standard treatment delivered via group sessions with paper diaries for self-monitoring and feedback. As a second comparison, smartphone-based treatment was expected to produce larger weight losses than a control condition involving monthly weigh-ins with paper diaries for self-monitoring and feedback. Engagement with treatment, including attendance at clinic visits and adherence to self-monitoring, was also examined and compared between conditions.

METHODS

Design

The Live SMART randomized clinical trial involved allocation to 3 arms in a 2:2:1 ratio: group-based behavioral obesity treatment (GROUP); a primarily smartphone-based behavioral obesity treatment (SMART); and a control condition (CONTROL). A 2:2:1 ratio was used to ensure sufficient statistical power for the comparison of greatest interest involving the two conditions that were expected to have the most similar outcomes, GROUP and SMART. The primary outcome was mean weight change at the 18-month end of treatment. Treatment adherence and engagement, including frequency of self-monitoring and attendance at clinic visits, were secondary outcomes.

Recruitment and enrollment occurred in 4 waves between January 2013 and January 2015. Study advertisements were placed in print media, online, and in local radio programming. Interested individuals received an initial telephone screening for eligibility. Those who appeared eligible were invited to an in-person orientation session to confirm eligibility, complete informed consent procedures, and begin the baseline assessment. Approximately 1 week later, participants returned to the research center to learn their randomization and begin treatment.

A computer algorithm randomized participants to condition, using blocks of 5, and stratification by gender and cohort. Random assignment was kept confidential from the study investigators and staff until the moment of randomization. The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and conducted at the Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center of The Miriam Hospital and Brown University in Providence, RI, USA. The study protocol and informed consent procedures were approved by The Miriam Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Participants

Live SMART aimed to enroll 270 English-fluent and literate participants (30% men and 30% racial/ethnic minorities), aged 18–70 years old, with overweight/obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 25–45 kg/m2) who were willing to use electronic resources for weight loss if assigned to SMART. The exclusion criteria included: currently in another weight loss program; taking weight loss medication; weight loss of ≥ 5% of body weight during the past 6 months; currently pregnant, lactating, less than 6 months postpartum, or plans to become pregnant during the next 18 months; report of a heart condition, chest pain during periods of activity or rest, or loss of consciousness on the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q);15 report of a medical condition that would affect the safety of participating in unsupervised PA; inability to walk 2 blocks without stopping; history of bariatric surgery; report of conditions that in the opinion of the investigators would render the participant potentially unlikely to follow the protocol including terminal illness, plans to relocate, or a history of substance abuse, bulimia nervosa, or other significant uncontrolled or untreated psychiatric problem. Participants assigned to SMART who did not own a smartphone were provided with one, including voice and data service plan, for use during the trial. Participants were told they would be asked to return the loaned smartphone at the end of the trial, but upon completion of the final assessment they were given the option to keep the smartphone, with discontinued service, in lieu of receiving payment for assessment completion.

Interventions

Treatment in each condition began with a one-hour group session to set goals for weight loss, dietary intake, and PA, and to learn the procedures for self-monitoring and feedback. All participants were given an initial weight loss goal of 10% of their current body weight. To achieve this goal, participants were instructed to follow a low-calorie diet of 1,200–1,800 kcal/day depending on their baseline body weight, and gradually work towards performing 200 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week, with an emphasis on walking performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes.

Participants assigned to GROUP attended treatment sessions in groups of 15–20 participants weekly for 6 months, bi-weekly for the following 6 months, and monthly for the final 6 months. Group interventionists were masters-level dieticians and exercise physiologists; two were assigned to lead each group. They weighed each participant privately before the group meeting and tracked their weight loss progress on a graph. The format and content of the group meetings followed the approach used in the behavioral interventions of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and Look Ahead trials.16,17 The early sessions were focused on dietary education and skills training, which emphasized following a low-fat diet (< 30% of calories from fat). Participants were instructed to build a PA habit starting with 10 minutes on at least 5 days/week, and gradually increase in increments of 10 minutes/day until reaching 200 minutes/week. Behavioral skills such as stimulus control, meal planning, and problem solving were taught to facilitate adherence and to address common barriers to weight loss.1 The end of each session involved setting a personal behavioral goal (e.g., limit fried food to once per week, try exercising with a friend), and the start of the next session involved a review of progress towards goals. Participants were instructed to self-monitor their daily weight, dietary intake (noting the calorie and fat content of each food), and minutes spent physically active (only on days that PA was performed) using paper diaries and a nutritional reference book provided to them. The paper diaries were submitted at each treatment session and the interventionists returned them at the following session with brief written feedback consisting of praise, suggestions for further behavior change, and encouragement.

Participants assigned to SMART received the same general content as GROUP via 5-minute skills training videos delivered 3 times weekly for 6 months, then twice weekly for 6 months, and weekly for the final 6 months (144 lessons total). This content was developed specifically for the purposes of this research study and it was delivered via a study application (“app”) for smartphone devices. Once a video became available to a participant, it remained accessible until the end of their participation. Participants were instructed to use the free commercially available MyFitnessPal app for self-monitoring of daily weight, dietary intake, and PA minutes. The study interventionists that led the GROUP treatment retrieved these records electronically and used the study app to provide feedback at the same frequency as in the GROUP condition, with similar content and overall length. The study app also allowed participants in SMART to set up to three simultaneous behavioral goals to target, receive timed reminders, and report on their adherence (e.g., a participant setting a goal to prepare a lunch before leaving for work would receive a reminder in the morning and then indicate whether they prepared their lunch as planned). These data were available to the interventionist providing feedback. Lastly the app allowed participants to post brief messages that could be seen by all other SMART participants. Study interventionists conducted monthly individual weigh-ins with SMART participants lasting ≤10 minutes focused on evaluating progress toward the weight loss goal.

Participants assigned to CONTROL attended monthly weigh-ins lasting ≤10 minutes with study interventionists to evaluate progress towards the weight loss goals. At each visit, brief printed information pertaining to the benefits of weight loss and healthy eating and PA habits, but not behavioral strategies for weight loss or behavior change, was provided. As in the GROUP condition, participants were instructed to selfmonitor their daily weight, dietary intake (noting the calorie and fat content of each food), and minutes spent physically active using paper diaries and a nutritional reference book provided to them. The paper diaries were mailed to a study interventionist who returned them by mail with brief written feedback mirroring the content and frequency of the feedback provided in GROUP and SMART.

Outcomes

Assessments were conducted by masked staff members at baseline, 6-months, 12-months, and 18-months. Weight was measured on a calibrated scale in light clothing, without shoes; height was assessed with a wall-mounted stadiometer. Two measures were taken and averaged. Attendance at clinic visits (group sessions in GROUP and weigh-ins in SMART and CONTROL) was recorded by study interventionists. Participants received $25 at 6-months and $50 at 12- and 18-months for completing assessment procedures. Frequency of self-monitoring was recorded automatically by the MyFitnessPal app in SMART and by study interventionists in GROUP and CONTROL. As per previous research, adherence to daily dietary self-monitoring was defined as recording either 3 or more separate eating events or intake equaling 50% or more of the calorie goal for the day.18 Number of video lessons viewed in SMART was recorded automatically for each participant by the intervention platform.

Participant Characteristics and Covariates

Participant characteristics were collected via questionnaire at baseline, including gender, age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, and income category. Additional questionnaires were administered at each assessment and were used in the outcomes analysis as described below to address the potential for bias caused by missing data. These questionnaires included: self-reported type 2 diabetes status, the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale,19 the Perceived Stress Scale,20 the Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger subscales of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire,21 the Binge Eating Scale,22 the Power of Food Scale,23 estimated weekly energy expenditure from PA as measured by the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire,24 and the Technology Anxiety Scale.25

Statistical Approach

Inverse Probability of Retention (IPR) weighting was used to correct observed values of the primary outcome (weight loss) for participants’ differential propensity to remain in the study.26 We estimated these probabilities non-parametrically by fitting discrete-time survival models using the GBM package.27 At each time point, we modeled follow-up assessment completion as a function of BMI, treatment condition, baseline demographics and questionnaire scale scores.

Weighted Generalized Estimating Equation (WGEE) models with independence correlation matrix and robust standard errors were estimated using the GEEPACK package written in R.28 All available weight loss data at each time point were entered in these analyses, with the IPR weights correcting for possible selection bias. The mean response was modeled solely in terms of measurement time (0, 6, 12 and 18 months), treatment arm, and their interaction.

The primary outcomes analysis was repeated using baseline carried forward (i.e., no weight change) to account for missing data, given that this approach was frequently used in previous trials of behavioral obesity treatment. Given that the pattern of results and the model estimates were no different from those obtained from the WGEE models with IPR weighting, only the results of the latter models are reported.

Pairwise comparisons were performed for the proportion of clinic visits attended and for rates of self-monitoring of weight, diet, and PA (measured as proportion of days with a recording; also as proportion of weeks with at least one record for weight). Pairwise differences in both primary and secondary outcomes were declared significant based on a Bonferroni-adjusted two-sided alpha=.05/3 significance level.

Sample Size Calculations

Our primary aim was to demonstrate that SMART would be at least as efficacious as GROUP at end of treatment (18-months), and that both of these conditions would be superior to CONTROL. Longitudinal weight trajectories were simulated based upon common means of 100 kg at baseline. In all 3 study arms, variance was assumed to be an increasing function of the mean satisfying σ2=exp(.06*μ), and the correlation matrix was taken as continuous-time AR(1) with autocorrelation coefficient ϕ=0.985 per quarter of follow-up. Simulations allowed for 2.5% non-differential attrition per quarter of follow-up, reaching 15% at 18 months. No IPRW correction was taken into account.

With N=108 participants per condition, power was estimated at 83.6% at one-sided alpha=0.05 for testing the primary hypothesis that SMART would be at least as efficacious as GROUP, i.e. would show mean weight losses of at least ∆μSMART = 5 kg if the true mean weight loss in the GROUP was ∆μ GROUP = 8 kg. In formal terms, we sought to test H0: ∆μ SMART<(5/8)* ∆μ GROUP vs. H1: ∆μ SMART<(5/8)* ∆μ GROUP, assuming ∆μ GROUP= 8kg. With N=54 in CONTROL, power was estimated at 86.9% and 99.9% respectively for testing our secondary hypotheses that both SMART and GROUP would be superior to the expected 2 kg loss achieved in CONTROL, with each individual comparison conducted at one-sided alpha=0.025. This resulted in an imbalanced 2:2:1 study design (N=270 total targeted), implemented using 54 permuted blocks of size 5.

RESULTS

Participants

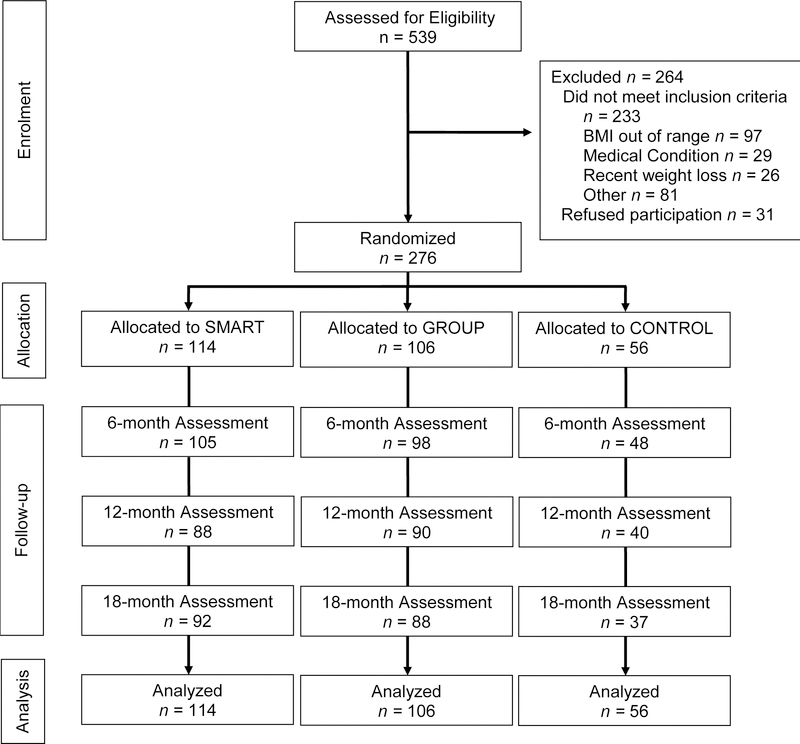

As depicted in Figure 1, showing participant flow through the trial, 539 individuals were screened for eligibility and 276 were randomized; 114 to SMART, 106 to GROUP, and 56 to CONTROL. Participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. The sample was predominantly female (83%) and White Non-Hispanic (92.8%). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 55.1 (9.9) years, weight was 95.9 (17.0) kg, and BMI was 35.2 (5.0) kg/m2. Of the 114 participants randomized to SMART, 38.6% were provided with a smartphone for use during the trial. Retention at 18-months was 66.1% in Control, significantly lower than the 80.7% in SMART and 83.0% in GROUP, which did not differ from each other. Every effort was made to obtain the outcomes data, even in cases where the participant had experienced illness, was temporarily out of town, etc. Thus, missing data almost exclusively represents loss to follow-up.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the trial.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| Total (N = 276) | |

|---|---|

| Gender, No. (%) | |

| Men | 47 (17.0) |

| Women | 229 (83.0) |

| Age, mean (SD), years Race, No. (%) |

55.1 (9.9) |

| Asian | 1 (0.4) |

| Black | 9 (3.3) |

| White | 260 (94.2) |

| More than one race | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 5 (1.8) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (2.5) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 269 (97.5) |

| Education, No. (%) | |

| High School or Less | 27 (9.8) |

| Some college | 70 (25.4) |

| College or University Degree | 92 (33.3) |

| Graduate Degree | 87 (31.5) |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | |

| Never Married | 34 (12.3) |

| Not Married | 4 (1.4) |

| Married | 186 (67.4) |

| Divorced | 36 (13.0) |

| Separated | 4 (1.4) |

| Widowed | 8 (2.9) |

| Other | 4 (1.4) |

| Employed Full Time | 174 (63.0) |

| Employed Part-time | 69 (25.0) |

| Annual Household Income, No. (%) | |

| Less than $25,000 | 12 (4.4) |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 39 (14.1) |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 93 (33.7) |

| $100,000 or more | 103 (37.3) |

| Don’t Know | 3 (1.1) |

| Prefer Not To Answer | 26 (9.4) |

| Owned a Smartphone, No. (%) | 171 (62.0) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 95.9 (17.0) |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 35.2 (5.0) |

| Binge Eating Scale, mean (SD) | 14.2 (7.8) |

| CES-D, mean (SD) | 9.3 (3.6) |

| Perceived Stress Scale, mean (SD) | 12.7 (6.5) |

| Power of Food Scale, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.9) |

| Technology Anxiety Scale, mean (SD) | 19.5 (8.0) |

| TFEQ | |

| Restraint Subscale, mean (SD) | 10.3 (4.1) |

| Disinhibition Subscale, mean (SD) | 9.6 (3.2) |

| Hunger Subscale, mean (SD) | 6.0 (3.4) |

CES-D indicates the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; TFEQ, Three Factor Eating Questionnaire.

Primary Outcome (Weight Change)

Intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficients were used to assess the need to model outcomes within the GROUP condition using 3-level models, with participants nested within interventionists. As the interventionist-level correlation was negligibly small (ICC<.0001), 2-level models with participant as the cluster identifier were used for all three study conditions.

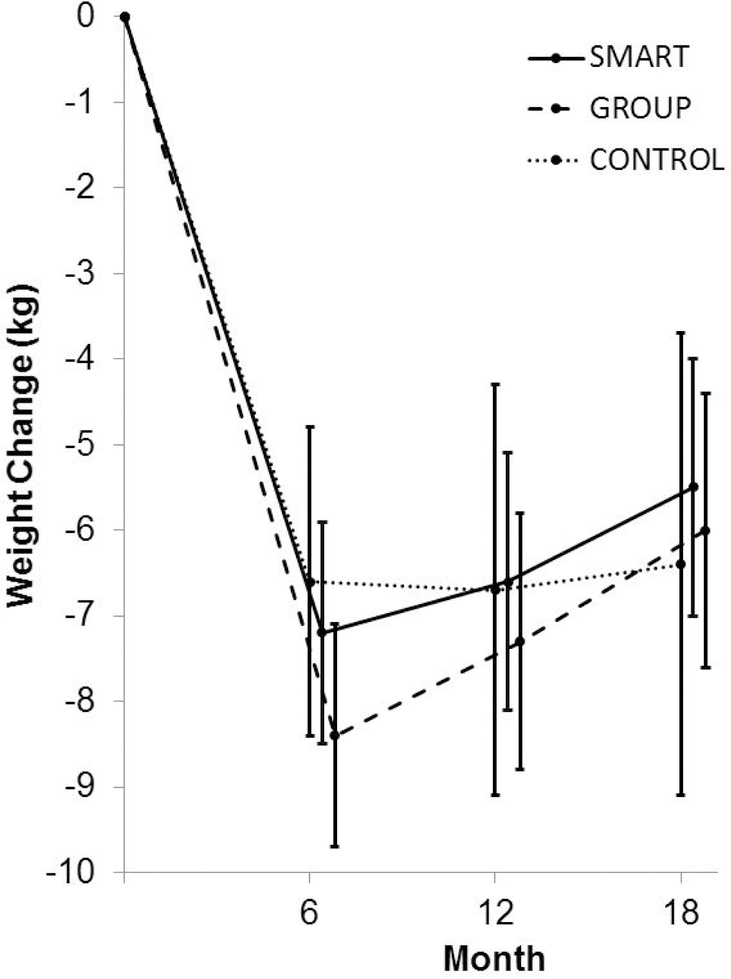

The previously described WGEE analyses indicated that all three conditions produced statistically significant reductions in weight at the 18-month primary endpoint, as shown in Figure 2. Consistent with hypotheses, the SMART condition produced an estimated 18-month weight loss of 5.5 kg (95% CI, 3.9 to 7.0) that did not significantly differ from the 5.9 kg (95% CI, 4.5 to 7.4) produced by GROUP. Contrary to expectations, CONTROL produced an estimated weight loss of 6.4 kg (95% CI, 3.7 to 9.2) that was indistinguishable from SMART. There were no statistically significant between-groups differences in weight loss at the 6-month or 12-month assessments (see Table 2 for values).

Figure 2.

Mean weight change over time by intervention assignment. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Table 2.

Weight Loss Outcomes by Condition

| 6-Months | 12-Months | 18-Months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Loss, mean (95% CI), kg | 7.2 (5.9 to 8.5) | 6.6 (5.1 to 8.0) | 5.5 (3.9 to 7.1) |

| SMART (n = 114) | |||

| GROUP (n = 106) | 8.3 (7.0 to 9.7) | 7.3 (5.8 to 8.8) | 5.9 (4.5 to 7.4) |

| CONTROL (n = 56) | 6.6 (4.8 to 8.4) | 6.7 (4.3 to 9.0) | 6.4 (3.7 to 9.2) |

| Weight Loss, mean (95% CI), % | |||

| SMART (n = 114) | 7.5 (6.1 to 8.8) | 6.8 (5.3 to 8.4) | 5.7 (4.1 to 7.4) |

| GROUP (n = 106) | 8.7 (7.4 to 10.1) | 7.6 (6.0 to 9.2) | 6.2 (4.7 to 7.7) |

| CONTROL (n = 56) | 6.8 (5.0 to 8.7) | 6.9 (4.5 to 9.4) | 6.7 (3.8 to 9.6) |

| Between Groups Differences, mean (95% CI), kg | |||

| GROUP versus SMART | 1.2 (−1.4 to 3.8) | 0.8 (−2.2 to 3.7) | 0.5 (−2.6 to 3.5) |

| CONTROL versus SMART | −0.6 (−3.7 to 2.5) | 0.1 (−3.8 to 4.0) | 1.0 (−3.5 to 5.4) |

| CONTROL versus GROUP | −1.8 (−4.9 to 1.3) | −0.7 (−4.6 to 3.3) | 0.5 (−3.9 to 4.9) |

Note: No statistically significant differences between groups at 6, 12, or 18-months. Percent weight loss expressed relative to a common baseline mean of 95.9 kg.

Secondary Outcomes (Treatment Engagement and Adherence)

There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of clinic visits (group sessions in GROUP and weigh-ins in SMART and CONTROL) attended across the three conditions. GROUP attended a mean 59.0% (95% CI 54.1 to 63.9) of 56 scheduled visits. Out of 19 scheduled visits, SMART attended 68.8% (95% CI 63.9 to 73.7) and CONTROL attended 61.1% (95% CI 52.4 to 69.8). Participants assigned to SMART viewed 72.4 (95% CI 57.8 to 87.0) video lessons across 18 months.

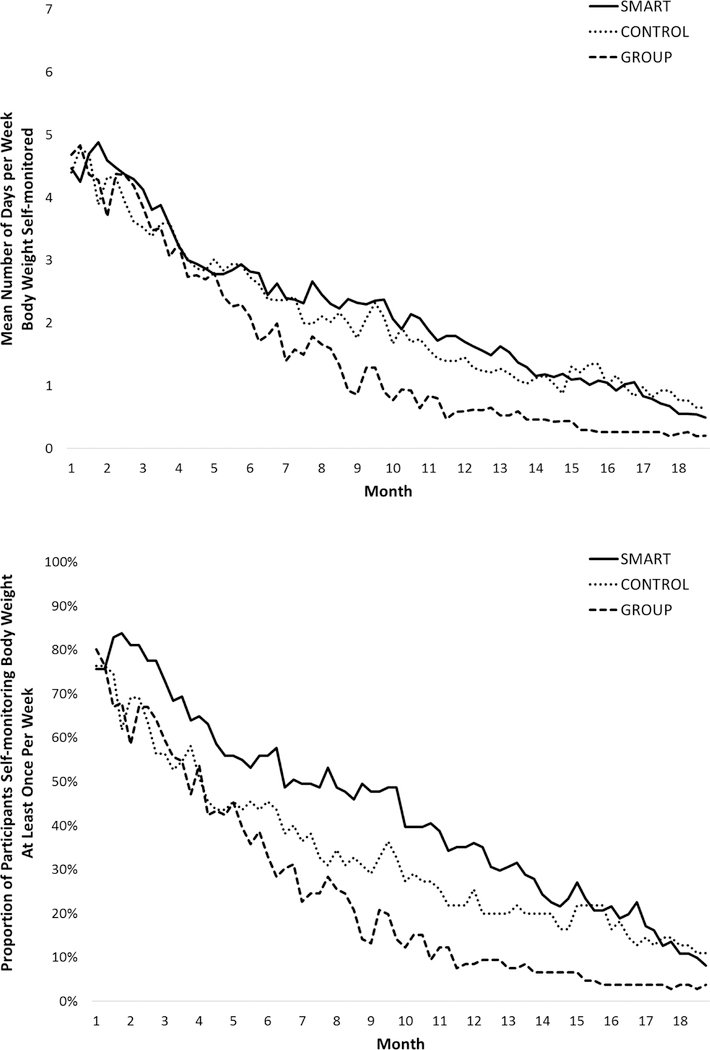

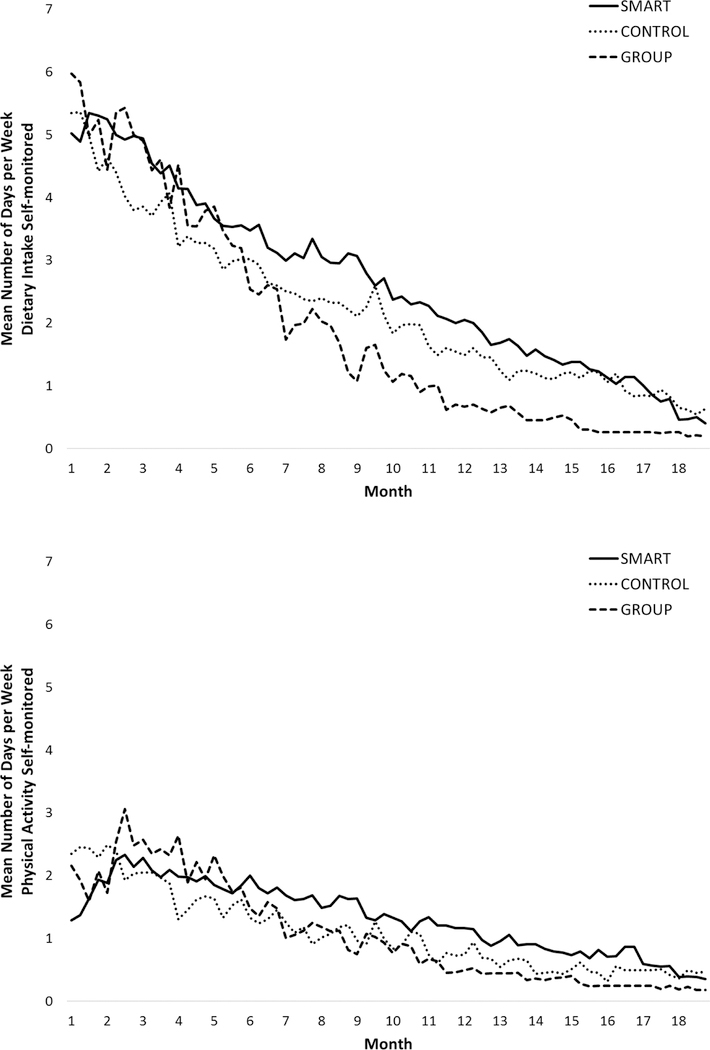

Rates of self-monitoring weight, diet, and PA decreased gradually over the course of the 18-month intervention period, as depicted in Figures 3 and 4. Rates of self-monitoring body weight were significantly lower in GROUP (21.2%; 95% CI 17.9 to 25.9) than in SMART (30.7%; 95% CI 26.2 to 37.2) and in CONTROL (29.7%; 95% CI 21.7 to 37.7), which did not differ from each other. The proportion of weeks in which at least one weight was recorded (a marker of clinically significant self-weighing) was significantly lower in GROUP (24.0%; 95% CI 19.9 to 28.1) than in SMART (42.9%; 95% CI 37 to 48.8) and in CONTROL (33.2%; 95% CI 26.9 to 39.5), which did not differ from each other. Diet was self-monitored on a significantly greater proportion of days in SMART (37.9%; 95% CI 32.6 to 43.2) compared to GROUP (27.5%; 95% CI 23.6 to 31.4) neither of which differed significantly from CONTROL (32.0%; 95% CI 24. to 40.0). The proportion of days that PA was self-monitored (only required on days that physical activity occurred), was not significantly different between SMART (18.9%; 95% CI 14.8 to 23), GROUP (15.2%; 95% CI 11.8 to 18.6), and CONTROL (15.6%; 95% CI 10.6 to 20.6).

Figure 3.

Self-monitoring of weight over time by intervention assignment.

Figure 4.

Self-monitoring of diet and physical activity over time by intervention assignment.

DISCUSSION

Behavioral obesity treatment reliably produces modest, clinically significant weight loss, but is not widely available outside of research studies due to the high cost of delivery and the need for specially trained interventionists.1,5 In this randomized clinical trial, we found that an 18-month behavioral obesity treatment delivered primarily via smartphone with monthly clinic weigh-ins produced weight losses no different from those obtained via the more intensive gold standard group-based approach. In contrast, the only previous trial to directly compare online and in-person behavioral obesity treatment, conducted by Harvey-Berino et al., found that a Web-based intervention consisting of group online meetings, weight loss lessons, and resources for self-monitoring and social support produced a lower mean (SD) weight loss of 5.5 (5.6) kg compared to 8.0 (6.1) kg in in-person treatment.10 The findings of Harvey-Berino et al. are consistent with several previous trials which demonstrate that online and mobile technology can be used to deliver behavioral obesity treatment, but short-term weight loss outcomes appear to be less than what is typically obtained via in-person treatment.

The SMART condition tested in this study was designed with two key elements that may explain why, in contrast to previous research, it achieved long-term weight loss outcomes that were comparable to those of GROUP. First, based on extensive evidence demonstrating the importance of self-monitoring for weight loss outcomes,11,12 and the potential of mobile technology to improve adherence to self-monitoring,13 SMART emphasized the use of smartphone-based tools to facilitate self-monitoring and provide timely feedback to foster accountability and support for adherence to recommended behavioral strategies. As expected, this emphasis resulted in superior adherence to self-monitoring of body weight and diet in SMART compared to GROUP. Few other studies have attempted to capitalize on the unique capabilities of smartphones, beyond text messaging, to facilitate key weight loss strategies such as self-monitoring over an extended period. Second, given prior research highlighting the importance of human contact for promoting accountability and support, particularly for weight loss maintenance,1 the SMART condition included brief monthly weigh-ins with a human interventionist. Contact with a human interventionist, particularly for the delivery of feedback on performance, has been shown to improve weight loss outcomes in online intervention.29

The SMART intervention could be considered a model for relying primarily on technology for behavioral intervention delivery while capitalizing on occasional brief contacts with human interventionists to provide supplementary accountability and support. Despite efforts to compensate physicians and other highly skilled providers for providing behavioral obesity treatment, it remains uncommon in the US due to the infeasibility of the clinical and financial model and lack of training in behavioral obesity treatment.30 However, as allied health providers such as nurses, dieticians, and pharmacists are increasingly tasked with taking the lead in supporting health behavior change,31 the SMART approach could represent a relatively low-cost method for delivering efficacious behavioral obesity treatment. Now that efficacy has been demonstrated, pragmatic trials studying implementation and effectiveness are needed to better understand how to integrate such interventions in routine and representative clinical care settings.

While SMART was expected to produce weight losses comparable to GROUP, CONTROL was not, and the positive outcomes achieved in CONTROL are counterintuitive. Gold-standard behavioral obesity treatment is intensive and costly, involving a wide range of individual intervention components that include, for example, goal setting, diet and physical activity education, training in a variety of cognitive and behavioral strategies to facilitate changes to diet and physical activity, self-monitoring of progress towards goals, feedback and problem-solving to address barriers to positive behavior change, and social support and accountability.1 To our knowledge, gold-standard behavioral obesity treatment has never been dismantled, and therefore relatively little is known about which intervention components most actively contribute to weight loss outcomes. However, the positive outcomes obtained in CONTROL suggest that self-monitoring, feedback, and whatever accountability and support can be obtained from a brief weigh-in, may be sufficient to produce clinically significant weight loss for motivated treatment-seeking individuals, and that more complex interventions such as GROUP and SMART may not always be necessary. CONTROL also included printed education regarding healthy diet and physical activity but education alone typically does not result in meaningful behavior change.32 Thus, the printed materials are unlikely to have contributed much to the weight losses in CONTROL. Additional research is needed to better understand for whom, and under what circumstances, a minimal intervention such as the CONTROL condition might be sufficient to produce clinically significant weight loss.

Strengths of this trial include the large sample size, the direct comparison of a primarily technology-driven behavioral obesity intervention to a gold-standard in-person intervention, analysis of adherence to self-monitoring, and the 18-month study period. Differential attrition, with greater dropout in the CONTROL condition, is a weakness of this study. The differential attrition may indicate that the technology used in SMART made it more acceptable to participants than CONTROL, or the provision of a smartphone to some participants in SMART may have incentivized retention. Alternatively, while CONTROL was described to participants as “monthly individual treatment,” and participants were not told that this condition was expected to produce less weight loss than the other two conditions, participants may have nevertheless inferred this on their own and therefore have chosen to drop out because they did not receive a treatment that was perceived as “better.” Other limitations include the preponderance of women and lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the sample.

CONCLUSIONS

This trial demonstrates the potential of a primarily smartphone-based behavioral obesity treatment with occasional remote and in-person human contact to produce weight loss no different than the more intensive gold-standard in-person treatment with regular group treatment sessions. Additionally, focusing the smartphone-based intervention on self-monitoring led to greater adherence to this key behavior than in inperson treatment. The combination of mobile technology with occasional low-intensity clinical contact could serve as one effective approach for addressing the problem of obesity in routine and representative clinical contexts.

STUDY IMPORTANCE QUESTIONS.

What is already known about this subject?

Behavioral obesity treatment has demonstrated efficacy for reducing weight, reducing disease risk and severity, and improving quality life.

Empirically validated behavioral obesity treatment is not widely available due to barriers such as cost, need for specially trained interventionists, and the need for frequent clinic visits to receive treatment. Behavioral obesity treatment has been adapted for online delivery but weight losses are often suboptimal.

Mobile technology can be used improve adherence to key behavioral obesity treatment strategies such as self-monitoring.

What does our study add?

This study directly compared behavioral obesity treatment delivered primarily via mobile technology (smartphone) to the gold standard group-based format and found no difference in weight loss outcomes; less intensive weight loss treatments involving mobile technology can yield similar weight losses to more intensive treatments delivered in-person.

Participants receiving treatment primarily via mobile technology self-monitored their weight and diet more often than those receiving group treatment.

A control group that involved monthly weigh-ins and brief printed information on weight loss also produced similar weight losses but attrition was higher, perhaps suggesting that this approach was less acceptable to participants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research team thanks the participants for their contribution to the research, without which the study would not have been possible.

Clinical Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov NCT01724632

Funding: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Sharing Statement

Proposals to access the study data should be directed to the corresponding author. To gain access, a data-sharing agreement is required that provides for (1) a commitment to use the data for research purposes only; (2) a commitment to securing the data using appropriate computer technology; (3) a commitment to destroying or returning the data after analyses are completed and (4) a commitment not to attempt to identify participants individually.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alamuddin N, Wadden TA. Behavioral treatment of the patient with obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2016;45:565–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab 2016;23(4):591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Font-Burgada J, Sun B, Karin M. Obesity and cancer: The oil that feeds the flame. Cell Metab 2016;23(1):48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34(7):1481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of Internet interventions: Review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med 2009;38(1):40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai AG, Asch DA, Wadden TA. Insurance coverage for obesity treatment. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106(10):1651–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manzoni GM, Pagnini F, Corti S, Molinari E, Castelnuovo G. Internet-based behavioral interventions for obesity: an updated systematic review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2011;7:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen B, Kornman KP, Baur LA. A review of electronic interventions for prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in young people. Obes Rev 2011;12:e298–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephens J, Allen J. Mobile phone interventions to increase physical activity and reduce weight: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013;28:320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey-Berino J, West D, Krukowski R, et al. Internet delivered behavioral obesity treatment. Prev Med 2010;51:123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker RC, Kirschenbaum DS. Self-monitoring may be necessary for successful weight control. Behav Ther 1993;24(3):377–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-monitoring in weight loss: A systematic review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111(1):92–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieffers JR, Hanning RM. Dietary assessment and self-monitoring with nutrition applications for mobile devices. Can J Diet Pract Res 2012;73(3):e253–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke LE, Styn MA, Sereika SM, et al. Using mHealth technology to enhance self-monitoring for weight loss: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:20–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Can J Sport Sci 1992;17(4):338–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care 2002;25(12):2165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity 2006;14(5):737–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas GJ, Wing RR. Health-E-Call, a smartphone-assisted behavioral obesity treatment: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2013;1:e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985;29(1):71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav 1982;7(1):47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowe MR, Butryn ML, Didie ER, et al. The Power of Food Scale. A new measure of the psychological influence of the food environment. Appetite 2009;53(1):114–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paffenbarger RS Jr., Blair SN, Lee IM, Hyde RT. Measurement of physical activity to assess health effects in free-living populations. Med Sci Sports Exer 1993;25(1):60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meuter ML, Ostrom AL, Bitner MJ, Roundtree R. The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. J Bus Res 2003;56(11):899–906. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogan JW, Roy J, Korkontzelou C. Handling drop-out in longitudinal studies. Stat Med 2004;23(9):1455–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridgeway G Generalized boosted regression models: GBM 2.1 package manual 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw 2006;15(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. A randomized trial comparing human e-mail counseling, computer-automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an Internet weight loss program. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1620–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batsis JA, Bynum JP. Uptake of the centers for medicare and medicaid obesity benefit: 2012–2013. Obesity 2016;24(9):1983–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA 2004;291(10):1246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016;136:109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]