Abstract

Background:

The tobacco industry spends billions on retail marketing and such marketing is associated with tobacco use. Previous research has not examined actual and potential exposures that adolescents have on a daily basis.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to determine whether both self-reported and geographically estimated tobacco retailer exposures differ by participant or neighborhood characteristics among urban and rural adolescents.

Methods:

The data for this study were part of a cohort study of 1,220 adolescent males residing in urban and rural (Appalachian) regions Ohio. The baseline survey asked participants how often they visited stores that typically sell tobacco in the past week (self-reported exposures). The number of tobacco retailers between home and school was determined using ArcGIS software (potential exposures). Adjusted regression models were fit to determine the characteristics that were associated with self-reported or potential exposures to retailers.

Results:

Adolescents who were non-Hispanic black or other racial/ethnic minority, had used tobacco in the past, and lived in rural areas had higher self-reported exposures. Urban adolescents, non-Hispanic black or other racial/ethnic minority, and those living in neighborhoods with a higher percentage of poverty had more potential exposures to tobacco retailers in their path between home and school.

Conclusions:

Rural adolescents had more self-reported marketing exposures than urban adolescents. However, urban adolescents had more potential tobacco exposures between home and school. Thus, point of sale marketing limitations might be a more effective policy intervention in rural areas whereas limits on tobacco retailers might be more effective for urban areas.

Keywords: Tobacco use, adolescent health, rural and urban health, built environment

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use among adolescents continues to be a major public health issue in the United States (US). In 2017, about 3.6 million middle and high school students used tobacco (1). Although adolescent cigarette smoking has decreased greatly in the past forty years, use of novel tobacco products has not declined as quickly. E-cigarettes, for example, were the most commonly used tobacco product among middle and high school students in 2017. Understanding the uptake of adolescent tobacco use is critical because nearly 90% of smokers start smoking by the age of eighteen (2), and the health-related financial impact of cigarette smoking alone amounts to $193 billion a year in the US (3).

Tobacco Marketing and Advertising

In 2016, about $9 billion was spent on retail tobacco marketing in the US, of which around 96% was targeted at the retailer (e.g., promotional and price discounts for wholesalers and retailers, coupons), (4). Retail marketing can be defined as any advertising that aims to increase sales at the location at which sales are actually made (5) and it includes signs within and outside of tobacco retailers, price discounts or promotional items given to customers at the retailer when a tobacco purchase is made, and promotional payments made by tobacco companies to retailers to have their products placed in locations at the retailer that are more likely to be seen by buyers. Retail marketing mainly affects impressionable buyers such as adolescents (2, 5) and leads them to misperceive the availability and popularity of tobacco (6), thus increasing their curiosity about tobacco products and risk of tobacco uptake (5, 7, 8). Adolescents also tend to receive a high level of tobacco marketing exposures particularly at the point of sale, further increasing their risk of uptake (9). In one large study of adolescents, simply recognizing a Newport advertisement was associated with a 1.5 odds of incident tobacco use over a one-year period (10).

Place and Youth Exposure to both Tobacco Retailers and Tobacco Marketing

The likelihood of exposure to tobacco retailers and marketing is heavily influenced by place factors, such as neighborhoods (low-income and minority neighborhoods), rural versus urban regions, and zones around schools. Each environment will be discussed below.

Low-income and racially/ethnically diverse neighborhoods have historically had a higher density of tobacco retailers and thus more tobacco marketing (11–13). Retailer density is an important measure to track because living close to tobacco retailers, such as convenience stores, has been associated with past-month smoking and increased tobacco purchases among adolescents (14). Moreover, low-income neighborhoods have more tobacco advertisements overall, and specifically more storefront advertisements (12, 13, 15). Tobacco retailers in low-income neighborhoods also display larger advertisements and market lower tobacco prices, which are features that appeal to adolescents (12).

Another place factor that is linked to tobacco use is urban versus rural status. Rural residents are more likely to use tobacco compared to residents of urban regions in the United States (16). Rates of tobacco use are particularly high in the Appalachian region of the US (17, 18). For example, in a study of male adolescents aged 11–16 years in Ohio, 23% of the Appalachian participants were ever tobacco users compared to 13% of the urban participants (19). Smoking cessation rates have also been found to be lower among Appalachian teenagers compared to urban teenagers (20). However, the density of tobacco retailers is lower in rural regions (21) and the types of advertising may be different in rural versus urban regions (13). In a study of tobacco retail practices in Ohio, advertisements were found to be more prevalent and more diverse in urban compared to rural Appalachian areas (21). Findings from a systematic review of 43 studies suggest that smokeless tobacco is more likely to be advertised in rural regions of the US (13).

Zones around schools are particularly important because research indicates that adolescents are more likely to try smoking if their school is in a high-density tobacco retail area (22). Adolescents are also likely to prefer brands advertised more heavily at retailers near their schools (9). In general, communities with more adolescents have a higher density of tobacco retailers (11). However, students in schools in low-income and minority communities are particularly at risk for exposure to tobacco marketing. Compared to higher income neighborhoods, tobacco retailers are more likely to be within 1000 feet of schools in low-income neighborhoods (12). Further, tobacco retailers near schools with high minority populations sell cigarettes at lower prices (23, 24) and advertise menthol cigarettes, such as Newport, more often (24), compared to shops near schools that are less racially and ethnically diverse.

Purpose of the Current Study

While research indicates that neighborhood differences can affect retail density near schools and homes, little is known about adolescents’ tobacco retailer exposures on their path between school and home. Since adolescents are especially sensitive to the neighborhood environment, it is important to study these exposures and their relation to tobacco use (25). This study examines daily exposures to tobacco retailers that adolescent boys experience as they travel to and from school in Franklin County, Ohio, an urban county, and 9 rural Appalachian Ohio counties. It is hypothesized that adolescents living in low-income urban neighborhoods will experience increased exposure.

METHODS

Participants

This study used data from a prospective cohort study which focused on adolescent tobacco initiation in urban and rural areas of Ohio. Participants (N=1,220) consisted of adolescent males aged 11 to 16 residing in any one of the 9 rural Appalachian counties, (Brown, Muskingum, Guernsey, Lawrence, Scioto, Clermont, Morgan, Noble, and Washington) or urban Franklin County in Ohio. Males are the focus in the parent study because dual use of smokeless tobacco and cigarettes was the primary outcome and smokeless tobacco use is rare among females.

Participants were recruited through either address-based probability sampling (ABS), which selected eligible households from the United States Postal Service’s address list, or through non-probability community-based sampling. The latter method used the following techniques to recruit eligible participants: advertising at community events, posting information on different media platforms, providing informative interviews, and giving participants literature to pass on to peers. Regardless of the sampling method, an interviewer set up a meeting time with the parent or legal guardian of the participant and completed the baseline session. The ABS sample and the community-based sample were merged to create the final analytical dataset.

Procedures

Before beginning the study, the Institutional Review Board at our university approved the protocol. Trained community interviewers obtained informed assent and permission from participants and parents or legal guardians and then conducted the baseline survey.

Measures

There were two outcome variables: 1) self-reported exposures at stores that serve as tobacco retailers, and 2) potential retailer exposures, which were probability estimates of retailer exposures based on home and school locations. The self-reported exposures were measured by interviewer-administered survey questions that asked participants to recall how many times they had visited each of the following store types in the past week: convenience stores or gas stations, grocery stores or supermarkets, liquor stores, and pharmacies. While not every store will have a tobacco license, previous research tells us that both in Ohio (21) and nationally (11), the majority of stores with a tobacco license will have advertising. Thus, self-reported visits to these types of stores are a good proxy for actual exposure to tobacco advertising. The total number of store visits in the past week was created by summing these self-reported visits. Because the distribution was skewed, exposures were categorized as 0, 1, 2–3, or 4 or more visits in the past week. Subjects missing data for number of visits to at least one store type were excluded from the analysis (n=12).

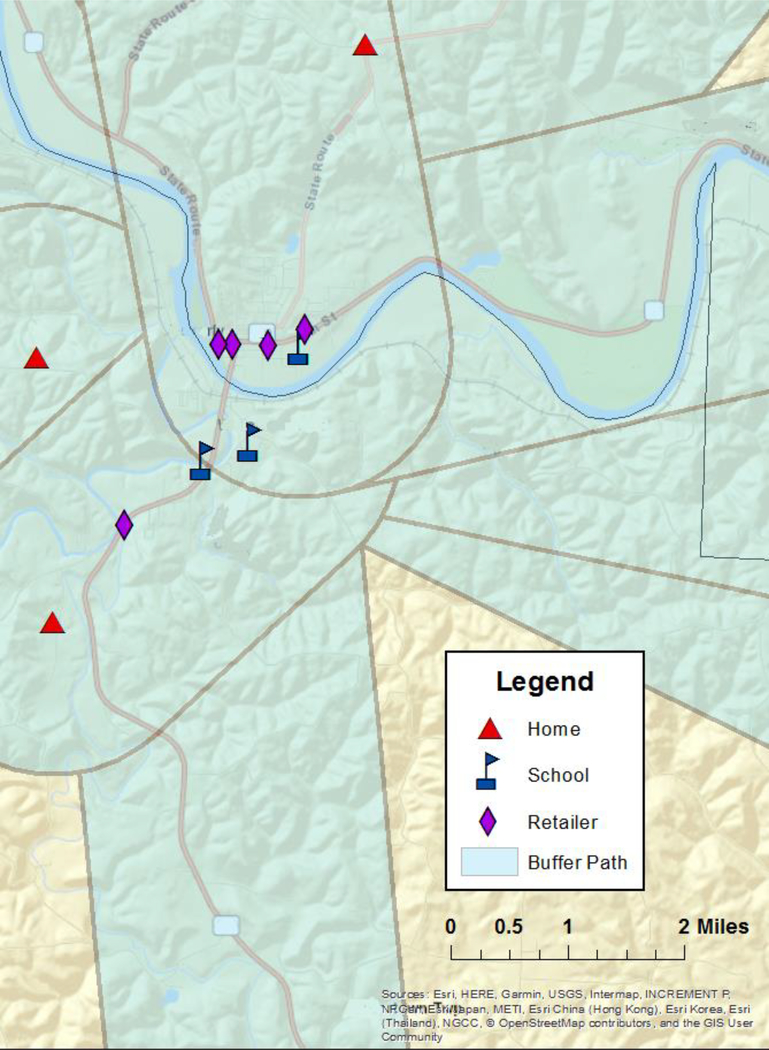

For retailers between home and school, we did not know the exact path that each participant took to travel to and from school. Therefore, we used a proxy, which was the total number of licensed tobacco retailers within a 1-mile buffer around the line between home and school. From a policy perspective, this is an approach that is consistent with how policies to reduce tobacco retailer densities are written. For example, policies could focus on reducing the number of retailers in a community or the number within a certain radius of schools (26). Potential retailer exposures were estimated using ArcGIS software (28). We began with an Ohio basemap from ArcGIS and shapefiles of the Ohio counties of interest and their respective census tracts from the United States Census Bureau. Home address and school attended were collected in the surveys; we also obtained a list of all retailers who had tobacco licenses within the ten counties. Next, ArcGIS was used to map the address coordinates as point shapefiles for the tobacco outlets, schools, and homes. The ArcGIS XY to line tool was then used to create a Euclidian distance line between home (origin) and school (destination) locations. This line was considered the theoretical path a boy took between home and school. Then the Create Buffer tool was used to create a one-mile buffer around each of these lines which captured the variety of different paths a boy could take. The resultant map showed a home point, a school point, a buffer around the path between these two points, and retail points within this buffer (Figure 1). Finally, the Join by Spatial Location operation was used to determine which homes belonged in which census tracts and how many retailers existed within particular buffer zones and ultimately how many retailers a boy could potentially pass by between home and school.

Figure 1:

ArcGIS Map Representation of Participant Home and School and Tobacco Retailers within the Home to School Path

Other measures from the baseline survey that were included in the analysis were age, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, and neighborhood characteristics. Age was measured continuously and later categorized as 11–13 or 14–16 so that we could examine differences by early versus middle adolescence. Race/ethnicity was coded as: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other race/ethnicity. Tobacco use was assessed as ever-use of any tobacco product (yes or no). County type was defined as either urban or rural. Neighborhood poverty was obtained from the 2015 American Community Survey data found on the United States Census Bureau’s FactFinder website (27). Tables containing the percent of families below the poverty line in each Ohio census tract were merged with the census tract shapefiles to categorize neighborhood income. Poverty level for the neighborhood in which the participant resides was categorized as either low or medium/high, with the cut point defined as the median for all census tracts in Ohio (below 11.2% versus at or above 11.2%).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were weighted and accounted for the stratified design. Stata version 14.2 (College Station, TX) was used for all analyses. We first generated weights for the probability sample (ABS sample), then calibrated weights for the non-probability sample and combined them together. The combined survey weights were further post-stratified to ensure the representativeness of the target population based on key identified covariates. Descriptive statistics were calculated overall and by region (urban versus rural). Age, race/ethnicity, and tobacco use status were included as descriptive measures.

Self-reported Retailer Exposures

Total number of visits in the past week to locations that typically sell tobacco (hereafter referred to as “visits to stores”) was the outcome for this analysis. First, the mean, standard error of the mean (SEM), and median number of visits were calculated and reported by participant characteristics, including age (11–13 versus 14–16 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, other), tobacco use status (never versus ever), county type (urban versus rural), and neighborhood poverty (low versus high). Next, univariable survey-weighted multinomial logistic regression models were used to evaluate the associations between each covariate and odds of visiting these stores 1, 2–3, and 4 or more times versus 0 times in the past week. Finally, starting with a multinomial logistic regression model including all covariates, backward selection with Wald tests (alpha = 0.05) was implemented to identify which predictors should remain in the final, adjusted model.

Potential Retailer Exposures

The potential exposures to tobacco retailers based on number of tobacco retail outlets within a participant’s home to school buffer was the outcome for this analysis. First, the mean, standard error of the mean, and median of store counts were calculated and reported by participant characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, tobacco use status, county type, and neighborhood poverty. Additionally, we examined the mean distance between home and school by person- and neighborhood-level factors. Next, survey-weighted negative binomial regression was used to model the rate of potential exposure to tobacco retailers in the buffer zone between home and school by each covariate. Negative binomial regression was used instead of Poisson regression due to the presence of overdispersion in the counts. Finally, starting with a fully-adjusted negative binomial regression model, backward selection using Wald tests (alpha=0.05) was used to identify which predictors were most strongly associated with increased rate of potential exposure to tobacco retailers in the buffer between home and school.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using the number of tobacco retailers within a 0.5-mile buffer to determine if the results from our model were stable or dependent on the chosen buffer. The modeling procedure described in the previous paragraph was repeated for the outcome number of retailers in the 0.5-mile buffer.

RESULTS

Summary Statistics

This study included 1,220 participants of whom 708 were from the urban county and 512 were from one of the nine rural Appalachian counties. ABS was used to recruit 991 participants, whereas the remaining 229 were recruited through community-based convenience sampling. Participants without complete data for all covariates (n=12), whose homes could not be geocoded (n=3), for whom we could not confirm the school address (n=46), who were home-schooled (n=2), who attended a school in another county (n=76), or crossed a non-study county on their way to school (n=6) were excluded from all analyses (n=140 total exclusions). Table 1 includes the weighted statistics from the sample.

Table 1:

Survey Weight Adjusted Distributions of Sociodemographic and Tobacco Use Characteristics of Participants, 2015–2016*

| Characteristic | Urban (n=619) | Rural (n=461) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SE) | 14.0 ± 0.07 | 13.9 ± 0.09 | 14.0 ± 0.06 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 63.4% | 91.9% | 71.1% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 22.5% | 1.2% | 16.7% |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.9% | 0.3% | 1.5% |

| Non-Hispanic Multi-racial | 6.4% | 5.5% | 6.1% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.9% | 1.2% | 4.6% |

| Any Tobacco | |||

| Never use | 86.6% | 76.6% | 83.9% |

| Ever use | 13.4% | 23.4% | 16.1% |

Weighted proportions calculated from subjects for whom a theoretical path from home to school could be calculated (n=1080).

Unweighted sample size is reported.

Statistical Findings

Self-Reported Exposures to Stores that Typically Sell Tobacco

On average, participants visited stores 4 times on average each week (median 3). Descriptively, 11–13 year olds visited stores that typically sell tobacco fewer times on average in the past week compared to 14–16 year olds (Table 2). Non-Hispanic white boys and “other” race/ethnicity boys visited these stores fewer times on average than non-Hispanic black boys. Ever-users of tobacco visited these stores more times on average in the past week. Boys living in rural areas and in medium/high poverty neighborhoods visited these stores more times on average in the past week than boys living in urban or low poverty areas, respectively.

Table 2:

Unweighted Median, Weighted Mean and Standard Error for Self-reported and Potential Exposures to Tobacco Retailers by Participant and Neighborhood Characteristics

| Characteristic | Median, Mean ± SEM for Self-reported Store Visits | Median, Mean ± SEM for Potential Exposures to Tobacco Retailers | Median, Mean ± SEM for Distance (in Miles) Between Home and School |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||

| Age | |||

| 11–13 | 3, 3.7 ± 0.2 | 11, 20.9 ± 1.5 | 2.2, 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| 14–16 | 3, 4.3 ± 0.2 | 13, 25.2 ± 1.8 | 2.9, 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3, 3.5 ± 0.1 | 9, 14.9 ± 0.9 | 2.5, 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4, 5.6 ± 0.5 | 43, 54.0 ± 4.1 | 3.2, 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| Other | 3, 4.6 ± 0.5 | 14, 27.1 ± 3.3 | 2.3, 3.4 ± 0.4 |

| Any Tobacco | |||

| Ever use | |||

| No | 3, 3.7 ± 0.1 | 12, 23.1± 1.3 | 2.5, 3.6 ± 0.2 |

| Yes | 4, 5.5 ± 0.4 | 12, 22.0 ± 2.9 | 3.1, 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| Current use | |||

| No | 3, 3.8 ± 0.1 | 12, 23.0 ± 1.2 | 2.5, 3.7 ± 0.1 |

| Yes | 5, 6.4 ± 0.9 | 12, 21.2 ± 4.0 | 4.0, 5.2 ± 0.6 |

| Neighborhood | |||

| County type | |||

| Rural | 3, 4.3 ± 0.2 | 5, 8.2 ± 0.4 | 3.8, 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| Urban | 3, 3.8 ± 0.2 | 16, 28.4 ± 1.5 | 2.2, 3.3 ± 0.2 |

| Neighborhood Poverty | |||

| Low poverty rate | 3, 3.4 ± 0.2 | 9, 16.4 ± 1.2 | 2.2, 3.4 ± 0.2 |

| Medium/high poverty rate | 3, 4.8 ± 0.3 | 24, 33.9 ± 2.1 | 3.2, 4.5 ± 0.2 |

Age was not related to self-reported visits to stores that typically sell tobacco in univariable multinomial logistic regression analyses (Table 3). With respect to race/ethnicity, non-Hispanic black boys had higher odds of visiting these stores 4 or more times versus 0 times in the past week compared to non-Hispanic white boys (odds ratio (OR) 3.19, 95% CI 1.29–7.85). Ever-users of tobacco had higher odds of visiting these stores 4+ times per week (OR 3.93, 95% CI 1.29– 7.85) versus 0 times per week than never users of tobacco. Boys living in urban areas had a lower odds of visiting stores 4+ times (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33–0.96) and those living in neighborhoods with medium/high poverty rate had higher odds of visiting these stores 2–3 (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.28–4.44) or 4 or more times (OR 3.01, 95% CI 1.65–5.52) in the past week compared to 0 times.

Table 3:

Weighted Univariable Results from Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Self-reported Visits to Tobacco Retailers (OR and 95% Confidence Intervals)1

| 1 vs. 0 | Visits to Stores 2–3 vs. 0 | 4+ vs. 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||

| Individual | |||

| Age | |||

| 11–13 | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| 14–16 | 1.21 (0.62, 2.38) | 1.19 (0.65, 2.16) | 1.76 (0.98, 3.17) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.02 (0.35, 2.96) | 1.86 (0.73, 4.76) | 3.19 (1.29, 7.85) |

| Other | 0.98 (0.30, 3.24) | 2.06 (0.72, 5.86) | 2.61 (0.94, 7.29) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Never | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Ever | 1.04 (0.36, 3.02) | 1.90 (0.73, 4.97) | 3.93 (1.56, 9.88) |

| Neighborhood | |||

| County Type | |||

| Rural | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Urban | 0.87 (0.48, 1.60) | 0.75 (0.43, 1.32) | 0.56 (0.33, 0.96) |

| Neighborhood Poverty | |||

| Low poverty rate | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Medium/high poverty rate | 1.17 (0.58, 2.33) | 2.38 (1.28, 4.44) | 3.01 (1.65, 5.52) |

Bold for a statistically significant result

Factors associated with visits to stores in weighted multivariable analyses included race/ethnicity, tobacco use, and urban/rural status (Table 4). In the adjusted model, non-Hispanic black boys were still more likely to visit stores 4 or more times versus 0 times per week than non-Hispanic white boys (OR 4.06, 95% CI 1.59–10.38). Boys of other race were also more likely to visit stores than non-Hispanic white boys 4 or more times versus 0 times (OR 3.20, 95% CI 1.13–9.07). Ever-users of tobacco remained significantly more likely to visit 4 or more times (OR 3.37, 95% 1.33–8.54) versus 0 times in the last week compared to never users of tobacco. Adolescents residing in urban areas continued to have lower odds (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.22–0.74) of visiting stores at the highest frequency compared to adolescents residing in rural areas.

Table 4:

Weighted Multivariable Results from Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Self-reported Visits to Tobacco Retailers (OR and 95% Confidence Intervals)1

| 1 vs. 0 | Visits to Stores 2–3 vs. 0 | 4+ vs. 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||

| Individual | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.07 (0.36, 3.18) | 2.07 (0.79, 5.42) | 4.06 (1.59, 10.38) |

| Other | 1.01 (0.30, 3.38) | 2.24 (0.78, 6.47) | 3.20 (1.13, 9.07) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Never | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Ever | 1.01 (0.35, 2.90) | 1.76 (0.68, 4.61) | 3.37 (1.33, 8.54) |

| Neighborhood | |||

| County Type | |||

| Rural | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Urban | 0.82 (0.43, 1.57) | 0.63 (0.34, 1.15) | 0.41 (0.22, 0.74) |

Bold for a statistically significant result

Potential Retailer Exposures

On average, there were 22.9 potential exposures to tobacco retailers in the space between home and school. Descriptively, 11–13 year olds had fewer potential exposures to tobacco retailers in their home to school buffer compared to 14–16 year olds (Table 2). Non-Hispanic white boys and other race/ethnicity boys had fewer tobacco retailers between home and school, on average, than non-Hispanic black boys. Ever-users of tobacco and current users of tobacco had fewer tobacco retailers in their home-to-school buffers than never users or non-current users, respectively. Boys living in urban or higher poverty areas had more tobacco retailers between home and school, on average, than boys living in rural or low poverty areas, respectively. Table 2 also indicates that the distance between home and school vary by these same factors, which makes intuitive sense.

Weighted univariable results from the negative binomial regressions identified that the rate ratio (RR) of potential exposures between home and school for non-Hispanic black boys (RR 3.61, 95% CI 2.99–4.37) or boys of other race (RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.39–2.37) was higher than the rate for non-Hispanic white boys (Table 5). Youth living in medium/high poverty neighborhoods (RR 2.07, 95% CI 1.71–2.49) and urban neighborhoods (RR 3.48, 95% CI 3.03–4.00) also had a higher rate of potential exposures between home and school than boys living in neighborhoods with low poverty and rural neighborhoods.

Table 5:

Weighted Univariable Results from Negative Binomial Regression Predicting Rate of Potential Exposures to Tobacco Retailers (Rate Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals)1

| RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | |

| Individual | |

| Age | |

| 11–13 | ref. |

| 14–16 | 1.21 (0.99, 1.47) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3.61 (2.99, 4.37) |

| Other | 1.81 (1.39, 2.37) |

| Tobacco Use | |

| Never | ref. |

| Ever | 0.96 (0.72, 1.26) |

| Neighborhood | |

| County Type | |

| Rural | ref. |

| Urban | 3.48 (3.03, 4.00) |

| Neighborhood Poverty | |

| Low poverty rate | ref. |

| Medium/high poverty rate | 2.07 (1.71, 2.49) |

Bold for a significant result

In the final adjusted negative binomial model, race/ethnicity, county type, and neighborhood poverty were significantly related to potential exposures between home and school (Table 6). Non-Hispanic black boys (RR 2.07, 95% CI 1.64–2.62), other race/ethnicity boys (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00–1.53), boys living in urban areas (RR 2.96, 95% CI 2.54–3.45), and boys living in neighborhoods with medium/high poverty rates (RR 1.7, 95% CI 1.47–1.97) were exposed to increased rates of potential exposures between home and school.

Table 6:

Weighted Multivariable Results from Negative Binomial Regression Predicting Rate of Potential Exposures to Tobacco Retailers (Rate Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals)1

| RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | |

| Individual | |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.07 (1.64, 2.62) |

| Other | 1.24 (1.00, 1.53) |

| Neighborhood | |

| County Type | |

| Rural | ref. |

| Urban | 2.96 (2.54, 3.45) |

| Neighborhood Poverty | |

| Low poverty rate | ref. |

| Medium/high poverty rate | 1.70 (1.47, 1.97) |

Bold for a significant result

The results from the sensitivity analysis that used the 0.5-mile were nearly identical to the results from the model fit to the 1-mile buffer. We are confident that these results are giving us good information about the factors that increase the potential exposure to tobacco retailers between the home and school.

DISCUSSION

This study included both self-reported visits to tobacco retailers and potential exposures to retailers between home and school, which was a novel way to examine how adolescents are exposed to tobacco retailers and thus tobacco advertising and marketing. Using both measures, non-Hispanic black and other race/ethnicity male adolescents were significantly more likely to be exposed to retailers. Our findings are consistent with previous research indicating that exposure to tobacco marketing is typically higher among non-Hispanic black populations (12, 28–30). The ever tobacco use, neighborhood income, and rural/urban findings, were not consistent across models and will be discussed separately in the next few paragraphs.

Ever-use of tobacco was related to self-reported visits to stores that typically sell tobacco but not to the potential exposure to retailers between home and school. Consistent with other studies, this finding could imply that actual visits to stores that have a lot of tobacco marketing, like convenience stores, could increase the rate of incident tobacco use (5). Or, it is possible that reverse causation is at play and that ever users go to stores that sell tobacco more often after they become ever users because they want to purchase tobacco. Given the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is impossible to know the direction of the relation.

Interestingly, rural adolescents were more likely to visit stores that typically sell tobacco than their urban counterparts and urban adolescents had a greater number of retailers in the buffer between home and school. Urban areas have a higher density of tobacco retail outlets (21); thus, this latter finding is not unexpected. At least one previous study reported that rural youth were more likely to visit a convenience store in the past week compared to urban youth (30). When further examining our data, visits to convenience stores largely drove the difference between rural and urban adolescents. Rural areas have fewer grocery stores and more convenience stores (up to 74% of stores in a rural county in one study (31)). Previous research suggests that convenience stores have more tobacco advertising (11) and are more likely than other types of stores to sell tobacco products to underage adolescents (32). While urban adolescents had a great number of potential exposures between home and school, the confluence of more visits, less verifying of age before a purchase, and more tobacco advertising could be a contributor to the rural/urban differences in tobacco use. Future research should consider the impact of these factors on adolescent tobacco use.

Public Health Implications

The Master Settlement Agreement restricts the tobacco industry from directly or indirectly targeting youth through advertising (33); however, adolescents are still aware of and influenced by such tobacco marketing (2). Under Section 906(d) of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) of 2009 (34), the FDA has the ability to set some restrictions on the sale, distribution, and advertising of tobacco products but is greatly limited in its abilities by the First Amendment. It is more likely that under the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act state and local governments could regulate the time, place, and manner (although not content) of tobacco advertising (35). Our results suggest that different policy approaches may be needed for rural and urban areas, with rural areas benefiting from policies that reduce the amount of retailer advertising and urban areas benefiting from policies that reduce the density of retail outlets.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study is its use of a large sample which was also weighted to population totals for use in analysis, lending generalizability to the results. Additionally, this study uses multivariable regression models, which allowed us to identify which personal and neighborhood-level factors most strongly predict self-reported and potential exposures to tobacco retailers. This paper also adds to the literature on geographic disparities, particularly disparities in Appalachian counties. While Appalachian adolescents had fewer potential exposures to tobacco advertising, they had more actual visits to stores that historically sell (and thus market) tobacco, which adds to their risk of tobacco use. Lastly, the use of Geographic Information Systems technology in this study allows for new perspectives on the influence of the built neighborhood environment on adolescent exposures to tobacco retailers and their marketing.

One limitation to this study is the fact that the participants reported their store visits to the interviewer, which could have produced a social desirability bias. Moreover, not every store that the participant visited had a license to sell tobacco. Although, the stores we inquired about traditionally sell tobacco at a high rate. Additionally, there are other types of stores that have licenses to sell tobacco but were not captured in self-reported exposures. Further, the exact path between home and school and mode of travel are both unknown, meaning that our estimates of tobacco retailers within a path may not represent his true exposure. While our proxy method will allow for a reasonable estimate of potential exposure, it is not perfect and we encourage researchers to focus future efforts on examining ways to capture the exact path between home and school. Moreover, these two outcomes are not identical. They are, however, measuring conscious and potentially unconscious tobacco marketing exposures. It is also important to note that tobacco advertising varies greatly by tobacco retailer type, with convenience stores having more marketing than grocery stores, as noted above. We also recognize that the sample was not entirely random and parameter estimates may not be generalizable to other populations. Finally, because Appalachian Ohio is predominately non-Hispanic white, we could not examine neighborhood race/ethnicity as a predictor of visits to stores or potential exposures on the way to school.

Conclusions and Directions for the Future

This study is among the first to examine factors related to number of tobacco retailers between home and school. Demographic, tobacco-related, and place characteristics impact the overall likelihood of exposure to the tobacco retail environment. The results suggest that living in a rural area may be of particular concern, as adolescents in this area are exposed to retailers—and thus tobacco marketing—more frequently because they visit stores that typically sell tobacco (including convenience stores) more often; our data also suggests that these adolescents are using tobacco at a greater rate. Longitudinal data being collected for this data set will be particularly useful in helping to determine the long-term impacts of tobacco marketing exposure and will allow us to better solidify the impact of the neighborhood environment on adolescent tobacco use. Current and future results inform federal, state, and local regulations for restricting adolescent exposure to tobacco advertising.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number P50CA180908 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Wang TJ, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2012. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/factsheet.html ed. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahende JW, Loomis BR, Adhikari B, Marshall L. A review of economic evaluations of tobacco control programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009. January;6(1):51–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2016 - issued 2018. [Internet]. [cited 11/22/2017]. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2016-federal-trade-commission-smokeless-tobacco-report/ftc_cigarette_report_for_2016_0.pdf.

- 5.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriksen L, Flora JA, Feighery E, Fortmann SP. Effects on youth of exposure to retail tobacco advertising 1. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;32(9):1771–89. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Portnoy DB, Wu CC, Tworek C, Chen J, Borek N. Youth curiosity about cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and cigars: prevalence and associations with advertising. Am J Prev Med. 2014. August;47(2 Suppl 1):S76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schleicher NC, Johnson TO, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Tobacco outlet density near home and school: Associations with smoking and norms among US teens. Prev Med. 2016;91:287–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Haladjian HH, Fortmann SP. Reaching youth at the point of sale: cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently. Tob Control. 2004. September;13(3):315–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauphinee AL, Doxey JR, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Racial differences in cigarette brand recognition and impact on youth smoking. BMC public health. 2013;13:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribisl KL, D’Angelo H, Feld AL, Schleicher NC, Golden SD, Luke DA, et al. Disparities in tobacco marketing and product availability at the point of sale: Results of a national study. Prev Med. 2017;105:381–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seidenberg AB, Caughey RW, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Storefront cigarette advertising differs by community demographic profile. Am J Health Promot. 2010. Jul-Aug;24(6):e26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JG, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russell S, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of neighborhood-level disparities in point-of-sale tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e8–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul CL, Mee KJ, Judd TM, Walsh RA, Tang A, Penman A, et al. Anywhere, anytime: retail access to tobacco in New South Wales and its potential impact on consumption and quitting. Soc Sci Med. 2010. August;71(4):799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frick RG, Klein EG, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Tobacco advertising and sales practices in licensed retail outlets after the Food and Drug Administration regulations. J Community Health. 2012. October;37(5):963–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Stanton CA, Quisenberry AJ, Villanti AC, Gaalema DE, et al. Rural vs. urban use of traditional and emerging tobacco products in the United States, 2013–2014. Am J Pub Health. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Northridge ME, Vallone D, Xiao H, Green M, Weikle Blackwood J, Kemper SE, et al. The importance of location for tobacco cessation: rural-urban disparities in quit success in underserved West Virginia Counties. J Rural Health. 2008. Spring;24(2):106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An examination of substance use among Medicaid-enrolled adults and comparison populations in Ohio. [Internet].; 2016 []. Available from: http://grc.osu.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/SubstanceBriefFINAL.pdf.

- 19.Friedman KL, Roberts ME, Keller-Hamilton B, Yates KA, Paskett ED, Berman ML, et al. Attitudes towards tobacco, alcohol, and non-alcoholic beverage advertisement themes among adolescent boys. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;13:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horn KA, Dino GA, Kalsekar ID, Fernandes AW. Appalachian teen smokers: not on tobacco 15 months later. Am J Public Health. 2004. February;94(2):181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts ME, Berman ML, Slater MD, Hinton A, Ferketich AK. Point-of-sale tobacco marketing in rural and urban Ohio: Could the new landscape of Tobacco products widen inequalities? Prev Med. 2015. December;81:232–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Cowling DW, Kline RS, Fortmann SP. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev Med. 2008. August;47(2):210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantrell J, Ganz O, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Harrell P, Kreslake JM, Xiao H, et al. Cigarette price variation around high schools: evidence from Washington DC. Health Place. 2015. January;31:193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, Fortmann SP. Targeted advertising, promotion, and price for menthol cigarettes in California high school neighborhoods. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, Adams SH, Irwin CE Jr, Brindis CD. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2009. July;45(1):8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers AE, Hall MG, Isgett LF, Ribisl KM. A comparison of three policy approaches for tobacco retailer reduction. Prev Med. 2015. May;74:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American community survey (ACS) 2015. [Internet]. []. Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- 28.Frick M, Castro MC. Tobacco retail clustering around schools in New York City: examining “place” and “space”. Health Place. 2013. January;19:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuang YC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA. Effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic status and convenience store concentration on individual level smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005. July;59(7):568–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders-Jackson A, Parikh NM, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP, Henriksen L. Convenience store visits by US adolescents: Rationale for healthier retail environments. Health Place. 2015. July;34:63–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liese AD, Weis KE, Pluto D, Smith E, Lawson A. Food store types, availability, and cost of foods in a rural environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007. November;107(11):1916–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson DC, Song L, Valdez RB, Angulo AS. Youth tobacco sales in a metropolitan county: factors associated with compliance. Am J Prev Med. 2007. August;33(2):91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Master Settlement Agreement | Public Health Law Center [Internet]. [cited 11/22/2017]. Available from: http://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/tobacco-control/tobacco-control-litigation/master-settlement-agreement.

- 34.Family smoking prevention and tobacco control act. [Internet].; 2009 [cited 7/22/2018]. Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ31/pdf/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 35.Cigarette Labeling and Advertising [Internet].; 1966 [cited 11/22/2017]. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/statutes/federal-cigarette-labeling-advertising-act-1966/federal_cigarette_labeling_and_advertising_act_of_1966.pdf