Abstract

Background:

People who inject drugs (PWID) have high rates of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection. Little is known about the rates of diagnosis and treatment for HCV among PWID. Therefore, this study aims to characterize the cascade of care in Vancouver, Canada to improve HCV treatment access and delivery for PWID.

Methods:

Data were derived from three prospective cohort studies of PWID in Vancouver, Canada between December 2005 and May 2015. We identified the progression of participants through five steps in the cascade of care: (1) chronic HCV; (2) linkage to HCV care; (3) liver disease assessment; (4) initiation of treatment; and (5) completion of treatment. Predictors of undergoing liver disease assessment for HCV treatment were identified using a multivariable extended Cox regression model.

Results:

Among 1571 participants with chronic HCV, 1359 (86.5%) had ever been linked to care, 1257 (80.0%) had undergone liver disease assessment, 163 (10.4%) had ever started HCV treatment, and 71 (4.5%) had ever completed treatment. In multivariable analyses, HIV seropositivity, use of methadone maintenance therapy, and hospitalization in the past 6 months were independently and positively associated with undergoing liver disease assessment (all P < 0.001), while daily heroin injection was independently and negatively associated with undergoing liver disease assessment (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Among this cohort of PWID, few had been started on or completed treatment for HCV. Our findings highlight the need to improve the prescribing of HCV treatment among PWID with active substance use.

Keywords: cascade of care, harm reduction, hepatitis C, injection drug use, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) is a leading cause of liver-related death worldwide, with an estimated 1.0% of the global population chronically infected with the virus.1–3 People who inject drugs (PWID) account for the majority of new and existing HCV infections, particularly in high-income countries where they account for 80% of new cases.3,4 With an estimated seroprevalence of 60–80%, PWID represent a large reservoir for transmission of HCV via sharing of drug preparation and injection equipment.4 5

Since 2014, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment has become available in the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada for the treatment of HCV and has a shorter course and significantly fewer side effects compared to the previous interferon-based regimens.6,7 DAA treatment has been shown to be highly effective with cure rates up to 95%.8 Numerous studies have disproven previous concerns over poor treatment adherence and repeat infection among PWID, and therefore guidelines from the WHO and most of the major Gastroenterology and Infectious Disease associations recommend consideration of treatment within this population.9–17 Despite this, access to HCV treatment among PWID remain low in many settings.18–20

Initially developed to understand and improve delivery of HIV treatment, the cascade of care has been adapted to enhance our understanding of each step in the continuum of HCV care from diagnosis through linkage to care, investigations, initiation and completion of treatment. Given the large burden of disease and potential for transmission of HCV among PWID, understanding the barriers to progression through the care cascade can be used to inform policy and guidelines and thereby enhance HCV care. Particularly in areas with a high prevalence of HCV infection such as Vancouver, it has been shown that a significant scale-up of treatment rates is required in order to impact transmission and chronic prevalence.21 The purpose of this study is to characterize the HCV cascade of care among PWID in Vancouver, BC, as well as to identify factors associated with undergoing liver disease assessment for HCV treatment in order to improve treatment delivery and decrease transmission of HCV.

METHODS

Data for this study was obtained as part of three ongoing prospective cohort studies of PWID in Vancouver: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS), the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS), and the At-Risk Youth Study (ARYS). Detailed descriptions of these cohorts have been previously published elsewhere.22–24 In brief, VIDUS enrolls HIV-seronegative adults who injected illicit drugs in the month before baseline assessment. ACCESS enrolls HIV-seropositive adults who used an illicit drug other than or in addition to cannabis in the month before the baseline interview. ARYS enrolls street-involved youth aged 14 to 26 who used an illicit drug other than cannabis in the month before the baseline interview. The studies use harmonized data collection and follow-up procedures to allow for combined analyses of the different cohorts. At baseline and semi-annually thereafter, data were collected through a combination of interviewer-administered questionnaire and blood testing for HIV and Hepatitis C Virus antibodies (anti-HCV), or HIV disease progression among those living with HIV infection. The studies were approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent was obtained from participants by trained research staff.

Study Participants

Participants were eligible for the present study if they completed the baseline interview and at least 1 follow-up visit between December 1, 2005 and May 31, 2015. The sample was further restricted to those who were anti-HCV positive at baseline or became positive during follow-up and completed at least one follow-up visit after anti-HCV seroconversion; reported a history of injection drug use at a visit when their blood sample tested positive for anti-HCV; and did not die during the study period. Death of participants was obtained using data linkage through the provincial Vital Statistics database. Participants were excluded if there was discordance between their self-reported HCV status and anti-HCV serostatus obtained through bloodwork as they did not answer the questions related to the cascade of care unless they self-reported being HCV-seropositive.

Cascade of Care Definitions

The steps in this cascade of care are: (1) chronic HCV, (2) linked to care, (3) liver disease assessment, (4) started treatment, and (5) completed treatment. As mentioned above, the study protocols involved obtaining blood samples for anti-HCV at baseline and at semi-annual follow-up visits, providing the number of anti-HCV positive participants. Since Hepatitis C RNA test, the confirmatory test for chronic hepatitis C infection, was not conducted through the study protocol, the number of chronic HCV cases was ascertained by (a) answering “no” to the question, “Since you tested positive, have you been told by a doctor that you no longer have Hep C?” or (b) answering “yes” to the question and having previously been treated for HCV. Linkage to care was identified by participants answering “yes” to at least one of the following questions: “Do you have a doctor that you see regularly about your HCV?” or “Have you ever seen a specialist doctor about your HCV?”. Liver disease assessment was defined as selfreporting that any of bloodwork, liver ultrasound, liver biopsy or Fibroscan® had been done as related to workup for HCV treatment. Participants were then asked whether they have ever taken and/or completed HCV treatment. In the questionnaire used between June 2014 and May 2015, participants were also asked whether they had ever been offered HCV treatment, and whether they decided to take HCV treatment when offered. For those who decided not to take HCV treatment, reasons for the decision were asked open-endedly. Answers with a similar idea but different wording were counted within the same category; for example, “I hear the drugs make you sick” and “I don’t think I can deal with the side effects” were coded as “concern over side effects”. This portion of the data was not added to the cascade of care but the descriptive statistics were reported in the results section.

Statistical Analyses

To determine those factors associated with undergoing liver disease assessment for treatment (i.e., any of bloodwork, ultrasound, Fibroscan® or liver biopsy related to investigation for HCV treatment), a set of explanatory variables was selected based on previous studies related to barriers to access to HCV treatment among PWID.25,26 As shown in Table 1, these included demographic characteristics (age, gender, and ethnicity), HIV seropositivity, homelessness, employment status, substance use (including alcohol, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, crack, benzodiazepines, and methadone maintenance therapy), HCV risk behaviour (syringe lending, unprotected sex, and sex work), hospitalization incarceration, and ever diagnosed mental health disorder(s). Definitions of the variables were consistent with those previously defined in other studies from these cohorts.23 All variables except for gender, ethnicity and a history of mental health disorder diagnoses referred to the past six months. First, the baseline characteristics of the participants who have and have not undergone liver disease assessment at baseline were compared based on the explanatory variables using the Pearson’s x2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

TABLE 1:

Baseline characteristics of 1571 participants who inject drugs with chronic HCV stratified by having undergone disease tagging

| Characteristic | Total | Underwent Disease Staging | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P-value | ||

| n (%) 1571 (100) |

n (%) 430 (27.4) |

n (%) 1141 (72.6) |

|||

| Male Gender | 1020 (64.9) | 285 (66.3) |

735 (64.42) | 1.08 (0.86–1.37) | 0.504 |

| Median age | 41.3 | 43.7 | 40.2 | <0.001 | |

| (IQR) | (33.7–47.6) | (37.2–49.9) | (32.9–46.9) | ||

| Caucasian | 936 (59.6) |

267 (62.1) |

669 (58.6) |

1.15 (0.92–1.45) | 0.227 |

| HIV positive | 555 (35.3) |

203 (47.2) |

352 (30.9) |

2.01 (1.60–2.52) | <0.001 |

| Homelessa | 578 (36.8) |

119 (27.7) |

459 (40.2) |

0.57 (0.45–0.73) | <0.001 |

| Heavy alcohol usea | 176 (11.2) |

46 (10.7) |

130 (11.4) |

0.93 (0.65–1.33) | 0.693 |

| Daily heroin injectiona | 434 (27.6) |

80 (18.6) |

354 (31.0) |

0.51 (0.39–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Daily cocaine injectiona | 142 (9.0) | 34 (7.9) |

108 (9.5) | 0.82 (0.55–1.23) | 0.336 |

| Daily methamphetamine injectiona | 87 (5.5) |

21 (4.9) |

66 (5.8) |

0.84 (0.51–1.38) | 0.486 |

| Daily crack usea | 593 (37.8) |

138 (32.1) |

455 (39.9) |

0.71 (0.57–0.90) | 0.005 |

| Benzodiazepine usea | 27 (1.7) |

9 (2.1) |

18 (1.6) |

1.33 (0.59–2.99) | 0.487 |

| Syringe lendinga | 71 (4.5) |

16 (3.7) |

55 (4.8) |

0.76 (0.43–1.33) | 0.331 |

| Methadone maintenance therapya | 668 (42.5) |

216 (50.2) |

452 (39.6) |

1.51 (1.21–1.89) | <0.001 |

| Unprotected Sexa,b | 509 (32.4) |

127 (29.5) |

382 (33.5) |

0.82 (0.64–1.04) | 0.106 |

| Hospitalizationa | 299 (19.0) |

94 (21.9) |

205 (18.0) |

1.28 (0.97–1.68) | 0.080 |

| Sex Worka | 238 (15.2) |

54 (12.6) |

184 (16.1) |

0.73 (0.53–1.02) | 0.063 |

| Employmenta | 346 (22.0) |

104 (24.2) |

242 (21.2) |

1.19 (0.91–1.54) | 0.204 |

| Incarcerationa | 273 (17.4) |

53 (12.3) |

220 (19.3) |

0.58 (0.42–0.80) | 0.001 |

| Mental illness | 766 (48.8) |

251 (58.4) |

515 (45.1) |

1.70 (1.36–2.13) | <0.001 |

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus. CI: Confidence Interval. IQR: interquartile range. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus. IV: Intravenous

Indicates behaviour during the six-month period prior to interviews

Unprotected sex was defined as vaginal or anal sex without a condom at least once

Then, among those who did not report having ever undergone liver disease assessment at baseline, we used multivariable extended Cox regression to determine factors associated with time to liver disease assessment, defined by a mid-point between the date of the first interview during which investigation(s) for treatment was/were reported and the preceding interview in which the participant reported having never undergone liver disease assessment. The same set of explanatory variables was used. An a priori-defined statistical protocol based on the examination of Akaike information criterion (AIC) and type III P values was used to construct a multivariable model. In brief, the full multivariable model first included all explanatory variables that were significantly associated with liver disease assessment at the P < 0.10 level in the bivariable analyses. After examining the AIC value of the models, the variable with the largest P value was removed and a reduced model was built. This iterative process was continued until a model with the lowest AIC value was selected. All P values were 2-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio, version 0.99.892 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics:

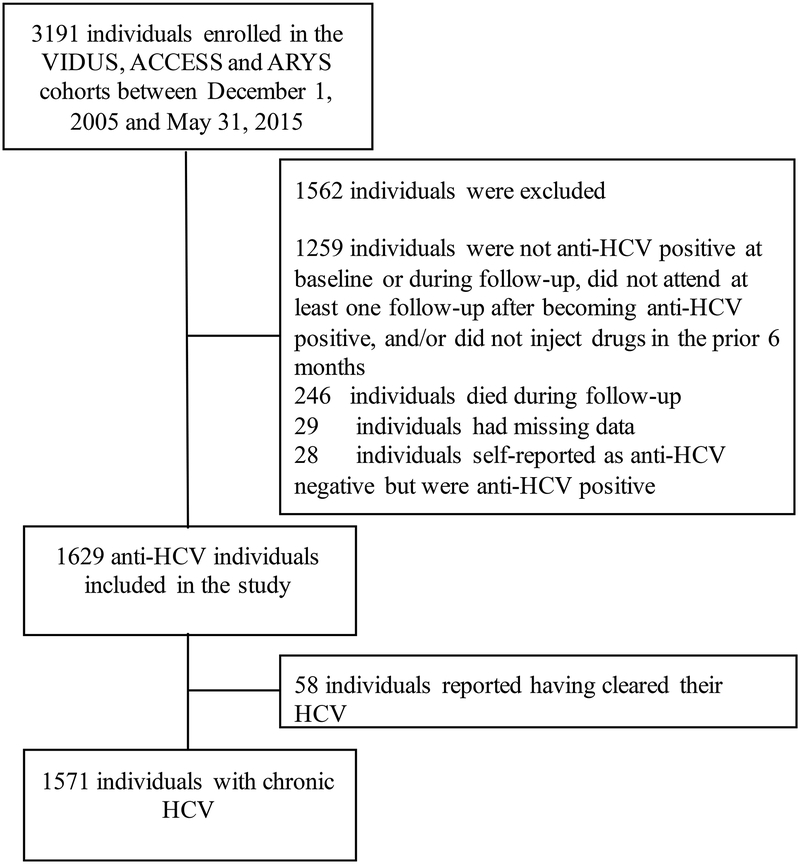

In total, there were 1932 participants with a positive anti-HCV blood test and a history of injection drug use who completed at least one follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, 246 participants were removed because they died during follow-up. A further 29 individuals were removed as they had missing or unknown data in one or more of the steps of the cascade of care. 28 participants were excluded for unknown HCV status in that they reported themselves as anti-HCV negative but were actually anti-HCV positive and therefore did not answer the cascade of care questions; none of the participants who reported being anti-HCV positive were wrong, giving a sensitivity of reporting of 0.98. Those with unknown HCV status were all HIV negative, younger (mean age 26.6 versus 40.1) and less likely to be white than the sero-matched participants. Of the 1629 individuals, 58 reported having being told by a physician that they had cleared their HCV, leaving a self-reported 1571 participants with chronic HCV who were followed for a median duration of 81.9 months (IQR, 30.7 – 102.5) and attended a median number of 10 follow-up visits (IQR, 4–15).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing how the sample of participants with chronic HCV (n = 1571) was derived from the cohorts of the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS), the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS), and the At-Risk Youth Study (ARYS), Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2005 – 2015.

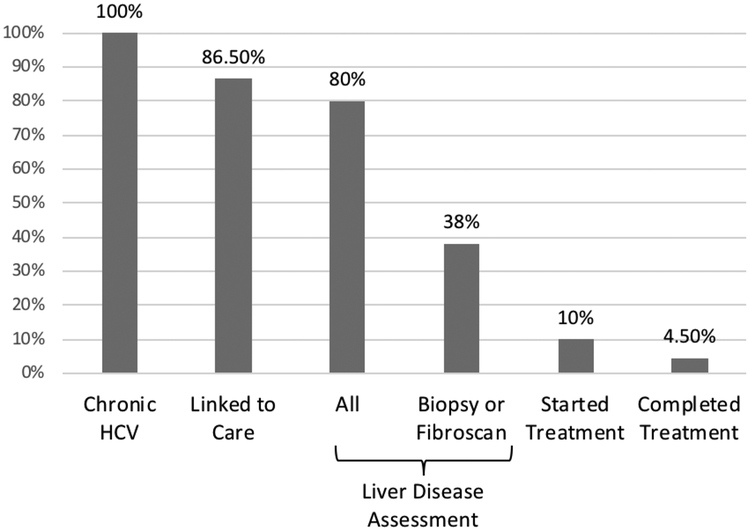

Cascade of Care

Diagrammatic representation of this cascade of care is found in Figure 2. Of the 1571 participants with chronic HCV, 1359 (86.5%) reported being linked to HCV care. A further 1257 (80.0%) reported having undergone liver disease assessment. The breakdown of investigations was: 1226 (97.5%) had bloodwork taken, 505 (40.2%) underwent Fibroscan®, 237 (18.9%) underwent ultrasound and 86 (6.84%) underwent a liver biopsy. Of those who had been investigated for treatment, 163 (10.4%) took treatment and 71 (4.5%) completed treatment.

FIGURE 2.

HCV cascade of care for PWID with chronic HCV in Vancouver, British Columbia (n = 1571). All data was derived from self-report questionnaires and Hepatitis C Virus antibody testing.

Factors associated with undergoing liver disease assessment for HCV treatment:

The baseline characteristics of those participants with chronic HCV stratified by whether or not they had undergone liver disease assessment are shown in Table 1. At baseline, 430 (27.3%) had undergone liver disease assessment. Compared to those who had not been investigated, those who reported having undergone liver disease assessment were more likely to be older (mean age 43.7 versus 40.2), HIV positive, on methadone maintenance therapy or to have ever been diagnosed with a mental health disorder while they were less likely to be homeless, inject heroin daily, smoke crack daily or have been in jail in the preceding 6 months (all P <0.01).

In the multivariable analysis shown in Table 2, HIV positivity (Adjusted Hazard Ratio [AHR] 1.75, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.50, 2.05), use of methadone maintenance therapy (AHR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.64) and hospitalization (AHR 1.50, 95% CI: 1.25, 1.81) remained independently and positively associated with having undergone liver disease assessment. Daily heroin injection in the past 6 months (AHR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.60, 0.86) remained independently and negatively associated with having undergone liver disease assessment.

TABLE 2.

Bivariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Analyses of Factors Associated with Undergoing Disease Staging among PWID (n= 1571)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (per 10 years older) | 1.14 (1.06 – 1.22) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.11 |

| Gender | 1.02 (0.89 – 1.17) | 0.82 | ||

| White | 1.13 (0.99 – 1.30) | 0.07 | 1.07 (0.93 – 1.24) | 0.35 |

| HIV positive | 1.96 (1.70 – 2.27) | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.50 – 2.05) | <0.001 |

| Homelessa | 0.75 (0.65 – 0.88) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.75 – 1.03) | 0.10 |

| Heavy alcohol usea | 1.12 (0.91 – 1.37) | 0.29 | ||

| Daily IV heroin usea | 0.58 (0.49 – 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.60 – 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Daily IV cocaine usea | 1.09 (0.86 – 1.38) | 0.46 | ||

| Daily IV methamphetamine usea | 0.84 (0.58 – 1.20) | 0.34 | ||

| Daily crack usea | 0.84 (0.73 – 0.97) | 0.02 | 0.89 (0.77 – 1.04) | 0.15 |

| Benzodiazepine usea | 0.99 (0.57 – 1.73) | 0.99 | ||

| Syringe lendinga | 0.93 (0.57 – 1.54) | 0.79 | ||

| Methadone Maintenance Therapya | 1.50 (1.31 – 1.72) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.23 – 1.64) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalizationa | 1.59 (1.33 – 1.90) | <0.001 | 1.50 (1.25 – 1.81) | <0.001 |

| Employeda | 0.97 (0.82 – 1.15) | 0.74 | ||

| Unprotected sexa,b | 0.88 (0.76 – 1.02) | 0.10 | 1.04 (0.88 – 1.21) | 0.15 |

| Sex trade worka | 0.93 (0.76 – 1.14) | 0.48 | ||

| Incarcerationa | 0.92 (0.76 – 1.11) | 0.38 | ||

| Mental Illness | 1.24 (1.08 – 1.42) | 0.002 | 1.11 (0.95 – 1.27) | 0.15 |

HR: Hazard Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Indicates behaviour in the previous six-months

Unprotected sex was defined as vaginal or anal sex without a condom at least once

Reasons for declining treatment when offered:

Out of the 1257 participants who underwent liver disease assessment, 989 (78.7%) completed at least one follow-up visit between June 2014 and May 2015 when the newer version of the questionnaire was used. Of those 989 participants, 460 (47.5%) reported ever having been offered treatment and, of those offered, 136 (29.6%) took treatment. Therefore, 324 (70.4%) participants who were ever offered treatment declined to take it. Reasons provided for declining to take treatment when offered are found in Table 3. The most common reasons provided included concerns over side effects (34.6%) and the sentiment that symptoms were not severe enough to start treatment (22.8%).

TABLE 3.

Reasons for declining to take HCV treatment when offered (n = 324)

| Reason | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Concern over side effects | 112 (34.6) |

| Symptoms are not severe enough to start treatment | 74 (22.8) |

| HCV is not a priority | 35 (10.8) |

| Need more information before deciding | 31 (9.6) |

| Don’t think I could comply with or finish treatment | 28 (8.6) |

| Started or continued using drugs | 24 (7.4) |

| Waiting for new drugs to become available | 24 (7.4) |

| Other health issues/interference with other health treatments | 23 (7.1) |

| Just offered/waiting to start | 18 (5.6) |

| Need better housing/no housing | 17 (5.3) |

| Pill burden | 13 (4.0) |

| Want to focus on HIV treatment/do not want to change HIV treatment due to HCV | 13 (4.0) |

| Don’t think I can reduce my drinking | 10 (3.1) |

| Depression/anxiety | 9 (2.8) |

| Poor treatment/discouraged by healthcare worker(s) | 9 (2.8) |

| Can manage HCV on my own | 8 (2.5) |

| Went to jail/just released | 6 (1.9) |

| Cost | 4 (1.2) |

| Other | 50 (15.4) |

DISCUSSION

This prospective study depicts the cascade of care for HCV among a cohort of PWID in Vancouver, Canada. Our results indicate that at least 80% of PWID with chronic HCV were linked to care with a physician and have undergone investigations related to treatment. This likely reflects the improvements in screening and referral for care noted in Canada and other high income settings.27,28 Specifically, in Vancouver, those with HIV or injection drug use have been shown to be more likely to be engaged in liver care than the general population.27 Within our study, rates of having undergone liver disease assessment were also high with the most common investigations being bloodwork (97.5%) and Fibroscan® (40.2%). In the past few years in BC, DAAs have become publicly-funded for patients with fibrosis stage F2 or greater (Metavir scale or equivalent) with additional specifications based on genotype. Acceptable methods to measure fibrosis include serum biomarker profile obtained from bloodwork (such as the AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index), Fibroscan®, or liver biopsy. Therefore, it is feasible to diagnose fibrosis and initiate treatment based on any of the investigations included in this study. We acknowledge that including bloodwork and ultrasound may overestimate the number of PWID who have been investigated for treatment, however based on our provincial guidelines, any of these methods could be appropriate.

Despite the improvements in linkage to care and investigations, there remains a large gap in initiation of treatment, with only 10% having started on treatment and less than half of those finishing treatment. These results are consistent with other HCV cascades of care in Canada, the United States and Australia showing low rates of treatment initiation, particularly among PWID, despite improvements in screening and linkage to care. 19,20, 27–34 Improving treatment initiation in PWID has been shown in mathematical modelling to reduce the prevalence of HCV and subsequent cirrhosis complications.33,35 Given the World Health Organization (WHO)’s priority of enhancing the diagnosis and treatment of PWID with HCV to control the spread of infection, our results highlight the ongoing importance of improving treatment initiation in this population.36 As DAAs have only recently been covered by the BC government, the treatment rates in our study predominantly reflect the pre-DAA era and rates may increase as these therapies become more widely accessible due to reduced financial barriers.

In the multivariable analysis, being HIV positive and hospitalized in the past 6 months were shown to be independently and positively associated with having undergone liver disease assessment. One can hypothesize that HIV positivity and recent hospitalization both offer an opportunity to connect with a physician and to have investigations facilitated more easily, which could explain the positive association with HCV investigations. This has also been shown in other HCV cascades of care.27,37 Our study also found that those on methadone maintenance therapy were more likely to undergo investigations for HCV treatment while those using injection heroin daily were less likely. This finding could potentially be explained by a reluctance of some physicians to prescribe HCV treatment to people with ongoing injection drug use26 despite guidelines to the contrary, although this cannot be assessed from our study and further research is needed.

Results from our sub-analysis indicate that there is also a barrier between participants being offered treatment and choosing to start treatment. Less than half of PWID with chronic HCV were ever offered treatment. Of those offered, less than a third decided to start treatment. This questionnaire was completed after DAA treatment regimens had been made available and publicly funded for advanced liver disease in British Columbia; however, answers pertained to treatment offered at any time, which would predominantly reflect interferon-based treatments. Previous estimates of willingness to take HCV treatment among PWID have been variable, ranging from 34–86%, with willingness being shown to decrease with increased awareness of side effects and relatively low cure rates of the interferon based regimens.38–42 Despite selfreported willingness to take up treatment, actual rates of treatment initiation remain low among PWID in our study as well as other studies, ranging from 1–16%18–20,39,43 The most common reasons for declining to take treatment - concern over side effects and feeling that symptoms were not severe enough to warrant treatment - are consistent with the findings of previous studies exploring reasons for refusing treatment among PWID.39,42,44 This highlights the potential for interventions to improve awareness of DAA regimens and their side effect profile as well as provide education related to the effects of HCV and potential morbidity if not treated.

There are limitations of this study that must be acknowledged. Firstly, the cohort studies from which the data was derived are comprised of a non-random sample and therefore may not be generalizable to local PWID or in other settings. Secondly, while the initial study sample was derived from an anti-HCV test, the remainder of the data was obtained through self-report. While self-report has been shown to be a valid measure among PWID,45 data is limited by the participant’s knowledge and memory of the investigations and treatment they have undergone or been offered. Without obtaining the confirmatory HCV RNA test, our sample of chronic HCV may be over-estimated as participants may be unaware that they had cleared their HCV or the test may not have ever been done. In Vancouver, it is estimated that nearly 75% of people who are anti-HCV positive go on to have RNA testing.27 We attempted to at least partly control for this by excluding those participants with mismatched self-reported HCV status and anti-HCV serodetection, thereby excluding those who self-report negative because they are aware that they have cleared the infection yet remain anti-HCV positive. Thirdly, data was not obtained on the degree of fibrosis among those who underwent investigations. Therefore, we are unable to determine what percentage of participants were eligible to receive publicly-funded treatment, which may explain some of the loss of participants moving to the treatment step of the cascade. Finally, there may be unmeasured confounders influencing whether or not participants underwent investigations for HCV treatment although our multivariable model attempted to account for many demographic, behavioural and social/structural factors.

In conclusion, this study has presented the cascade of care for PWID in Vancouver. While a large proportion of PWID progress through linkage to care and investigation steps of the cascade, few are ultimately started or complete HCV treatment. Qualitative findings from this study expose patient factors, including perceived side effects of HCV medications and a lack of symptoms, as potential barriers to achieving HCV eradication in this population. Further research is needed to better understand prescriber and patient factors that contribute to low rates of initiation of HCV treatment among PWID. Improved awareness and understanding regarding side effects of treatment and the morbidity associated with untreated HCV may help to improve treatment uptake to decrease the viral burden, and, ultimately, improve cure rates for HCV among PWID.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff.

FUNDING

The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (VIDUS & ARYS: U01DA038886, ACCESS: R01DA021525). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine which supports Dr. Evan Wood, as w ell as a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR] Foundation grant supporting Dr. Thom as K err (FDN-148476). Dr. Kora DeBeck is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR] / St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation- Providence Health Care Career Scholar Award and a CIHR New Investigator Award. Dr. Hayashi is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award (M SH-141971). Dr. Milloy is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award, an MSFHR Scholar Award and the US NIH (R 01-D A 0251525) His institution has received an unstructured gift from NG Biomed, Ltd., to support his research. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; p reparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the m an u scrip t for publication.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Bruggmann P, Grebely J. Prevention, treatment and care of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:S22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017:2:161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378:571–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pouget ER, Hagan H, Des Jarlais DC. Meta-analysis of hepatitis C seroconversion in relation to shared syringes and drug preparation equipment. Addiction. 2012;107:1057–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pockros PJ. Advances in newly developing therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Front Med. 2014;8:166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. NEngl J Med. 2014;370:1889–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MA, Chan J, Mohammad RA. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir: interferon-/ribavirin-free regimen for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aspinall EJ, Corson S, Doyle JS, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:S80–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backmund M, Meyer K, Von Zielonka M, Eichenlaub D. Treatment of hepatitis C infection in injection drug users. Hepatology. 2001;34:188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellard M, Sacks-Davis R, Gold J. Hepatitis C treatment for injection drug users: a review of the available evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:561–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robaeys G, Van Vlierberghe H, Mathei C, et al. Similar compliance and effect of treatment in chronic hepatitis C resulting from intravenous drug use in comparison with other infection causes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 18:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson M, Crawford V, Tippet A, et al. Community-based treatment for chronic hepatitis C in drug users: high rates of compliance with therapy despite ongoing drug use. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AASLD-IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed January 10, 2017.

- 15.Myers RP, Shah H, Burak KW, Cooper C, Feld JJ. An update on the management of chronic hepatitis C: 2015 Consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;60:392–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grebely J, Robaeys G, Bruggmann P, et al. Recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:1028–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alavi M, Raffa JD, Deans GD, et al. Continued low uptake of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in a large community-based cohort of inner city residents. Liver Int. 2014;34:1198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grebely J, Raffa JD, Lai C, et al. Low uptake of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in a large community-based study of inner city residents. J ViralHepat. 2009;16:352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta SH, Genberg BL, Astemborski J, et al. Limited uptake of hepatitis C treatment among injection drug users. J Community Health. 2008;33:126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin NK, Vickerman P, Grebely J, et al. Hepatitis C Virus treatment for prevention among people who inject drugs: Modeling treatment scale-up in the age of direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology. 2013;58:1598–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood E, Kerr T, Marshall BD, et al. Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA. 1998;280:547–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood E, Stoltz JA, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe D, Luhmann N, Harris M, et al. Human rights and access to hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:1072–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myles A, Mugford GJ, Zhao J, Krahn M, Wang PP. Physicians’ attitudes and practice toward treating injection drug users with hepatitis C: results from a national specialist survey in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:135–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janjua NZ, Kuo M, Yu A, et al. The Population Level Cascade of Care for Hepatitis C in British Columbia, Canada: The BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC). EBioMedicine. 2016;12:189–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier MM, Ross DB, Chartier M, Belperio PS, Backus LI. Cascade of Care for Hepatitis C Virus Infection Within the US Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:353–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viner K, Kuncio D, Newbern EC, Johnson CC. The continuum of hepatitis C testing and care. Hepatology. 2015;61:783–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarus JV, Sperle I, Maticic M, Wiessing L. A systematic review of Hepatitis C virus treatment uptake among people who inject drugs in the European Region. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, McManus H, et al. Chronic hepatitis C burden and care cascade in Australia in the era of interferon-based treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiessing L, Ferri M, Grady B, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection epidemiology among people who inject drugs in Europe: a systematic review of data for scaling up treatment and prevention. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin NK, Vickerman P, Hickman M. Mathematical modelling of hepatitis C treatment for injecting drug users. J Theor Biol. 2011;274:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iversen J, Grebely J, Carlett B, et al. Estimating the cascade of hepatitis C testing, care and treatment among people who inject drugs in Australia. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cousien A, Tran VC, Deuffic-Burban S, Jauffret-Roustide M, Dhersin JS, Yazdanpanah Y. Hepatitis C treatment as prevention of viral transmission and liver-related morbidity in persons who inject drugs. Hepatology. 2016;63:1090–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2021. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246177/1/WH0-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed January 10, 2017.

- 37.Cachay ER, Hill L, Wyles D, et al. The hepatitis C cascade of care among HIV infected patients: a call to address ongoing barriers to care. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strathdee SA, Latka M, Campbell J, et al. Factors associated with interest in initiating treatment for hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection among young HCV-infected injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:S304–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grebely J, Genoway KA, Raffa JD, et al. Barriers associated with the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein MD, Maksad J, Clarke J. Hepatitis C disease among injection drug users: knowledge, perceived risk and willingness to receive treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61:211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walley AY, White MC, Kushel MB, Song YS, Tulsky JP. Knowledge of and interest in hepatitis C treatment at a methadone clinic. JSubstAbuse Treat. 2005;28:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alavi M, Grebely J, Micallef M, Dunlop AJ, Balcomb AC, Day CA, et al. Assessment and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in the opioid substitution setting: ETHOS study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:S62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iversen J, Grebely J, Topp L, Wand H, Dore G, Maher L. Uptake of hepatitis C treatment among people who inject drugs attending Needle and Syringe Programs in Australia, 1999–2011. J ViralHepat. 2014;21:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swan D, Long J, Carr O, Flanagan J, Irish H, Keating S, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C testing, management, and treatment among current and former injecting drug users: a qualitative exploration. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darke S Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:253–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]