Abstract

Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) juice (BRJ) is a good source of betalain (betacyanins and betaxanthin) pigments and exhibits antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and chemo-preventive activities in vitro and in vivo. The current study was performed to determine the cardioprotective effect of BRJ on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant defense, functional impairment, and histopathology in rats with isoproterenol (ISP)-induced myocardial injury. Myocardial ischemia was induced by ISP (85 mg/kg) s.c. injection at 24 h intervals, followed by oral administration of BRJ for 28 days at doses of 150 and 300 mg/kg. ISP-induced myocardial damage was confirmed by an increase in heart weight to body weight ratio, % infarction size, serum cardiac indices (AST, ALT, GGT, ALP, LDH and CK-MB), and histological alterations in the myocardium. Pretreatment with BRJ (150 and 300 mg/kg) followed by ISP induction reduced oxidative/nitrosative stress and restored the cardiac endogenous antioxidants in rats. ISP augmented cardiac inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10), myeloperoxidase activity, NF-κB DNA binding and protein expression of NF-κB (p65), and the hyperlipidemia level was significantly reduced by the BRJ pretreatment. Furthermore, the BRJ pretreatment significantly reduced caspase-3, Bax, and MMP-9 protein expression, enhanced the Bcl-2 antiapoptotic protein expression, alleviated the extent of histological damage, myonecrosis, and edema, and maintained the architecture of cardiomyocytes. These findings suggest that BRJ pretreatment mitigates cardiac dysfunction and structural damages by decreasing oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in cardiac tissues. These results further support the use of BRJ in traditional medicine against cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Beetroot juice, Isoproterenol, Oxidative stress, Myocardial injury, Cardioprotection

Introduction

Myocardial ischemia (MI) is a common ischemic heart injury and a prominent cause of morbidity and mortality globally (Spodick 2004). Beetroot, also called shamandar, is a variety of Beta vulgaris L. (family: Chenopodiaceae) commonly grown for its edible taproot and used for its potent antioxidant properties (Winkler et al. 2005). It is also a source of nitrates, vitamins, minerals, and the nitrogenous water-soluble pigments, betalains, which have two main classes, red betacyanins and yellow betaxanthin (Lee et al. 2005; Vulic et al. 2014). The taproot of beet has a prolonged history of use in traditional medicine for the treatment of cancer and jaundice. These taproots also possess carminative, emmenagogic, hemostatic, and renoprotective properties (Vali et al. 2007; Al-Yahya et al. 2015; El Gamal et al. 2014).

Several investigations have demonstrated that beetroot ameliorates multiple diseases such as type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and dementia (Winkler et al. 2005; Curtis et al. 2015). Since beetroot is rich in dietary nitrate, it is widely used for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) (Lundberg et al. 2008). Isoproterenol (ISP), a β1- and β2-adrenoreceptor agonist, is a known cardiotoxin that is extensively used as a chemical model to induce MI in rats (Rona et al. 1963). When there is an imbalance in energy, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are formed and the structure of cardiomyocytes changes (Van Vleet et al. 2002). It is suggested that ROS and (nitric oxide synthase) NOS, with increased (lipid peroxidation) LPO and decreased antioxidant enzyme activity, might play a role in ISP-induced MI (Fan et al. 2013; Kalogeris et al. 2014). Given this background information, we investigated the effect of beetroot juice (BRJ) extract on ISP-induced cardiac damage in a rodent model.

Materials and methods

Collection and validation of plant material

Fresh ripe beetroots (Beta vulgaris L.) were procured in March 2014 from a local market in Saudi Arabia, validated by a plant taxonomist, and assigned a voucher specimen number (no. 256485).

Lyophilization of BRJ

The taproots were carefully washed, dried and cut into small pieces to obtain the juice, which was frozen at − 40 °C for 24 h and lyophilized using a Christ Alpha 1–4 LSC freeze dryer.

Total phenolic contents and in vitro DPPH assay

The phenolic content in BRJ was measured spectroscopically by the Folin–Ciocalteu method (Singleton et al. 1999) with gallic acid as a reference. The ROS scavenging capacity of BRJ was evaluated against 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) as previously described (El Gamal et al. 2014).

Identification of phytochemicals by UPLC-ESI-MS

The moieties in BRJ were identified by their molecular weights as determined by UPLC-ESI-MS. BRJ was prepared as per the procedure described by Kujala et al. (2002) prior to being subjected to the UPLC-ESI-MS analysis.

Animals and acute toxicity test

Wistar rats (190–215 g) were procured from the Experimental Animal Care Center, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and fed a pellet diet ad libitum. The study protocol was approved by the College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, and the animals were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The acute toxicity study was performed as per the limit test using the OECD test guidelines for acute toxicity test 401 (Oecd 1994).

Induction of MI in rats and study design

ISP, a β1- and β2-adrenergic agonist, is extensively used to induce MI in rodent models (Rona et al. 1963; Ojha et al. 2012). Animals were separated into four categories, each with six rats. Group A (NC) animals were administered normal saline (500 µL/rat) by gastric intubation for 28 days. Group B (ISP) animals were administered saline and ISP (85 mg/kg, s.c.) on days 27 and 28. Groups C and D animals received BRJ (150 and 300 mg/kg/day) orally for 28 days, with ISP simultaneously administered (85 mg/kg, s.c.) on days 27 and 28. The optimal doses of BRJ (150 and 300 mg/kg) used in this study were based on a pilot study (data not shown). Body weights of rats were verified at regular intervals. On day 29 (i.e., 24 h after the final ISP administration), rats were euthanized, and blood samples and heart tissue were procured. Serum and tissue homogenates were prepared as per a previous report (Al-Yahya et al. 2015). TP levels in tissue were evaluated using the Lowry reagent (Sigma-Aldrich).

Biochemical assessment

Serum levels of AST, ALT, GGT, ALP, LDH, and CK-MB were estimated using commercial kits, and the levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were determined using a previously described method (Assmann 1979; Al-Yahya et al. 2015), commercial kits and an automated analyzer (Dimension Xpand Plus system, Siemens, USA).

Evaluation of oxidative stress markers and pro-inflammatory cytokines

Biochemical parameters such as MDA (Zhou et al. 2008), NP-SH (Sedlak and Lindsay 1968), protein (Lowry et al. 1951), SOD (Peskin and Winterbourn 2000), CAT (Aebi 1974) and NO (Green and Reed 1998) in the homogenized cardiac tissue were estimated, and the cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10) levels in the heart were determined using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, USA) and the principle of sandwich ELISA.

Apoptotic marker protein expression, NF-κB (p65) DNA-binding and MMP-9 assay

Heart tissues from each group were homogenized in RIPA buffer to prepare cytosolic and nuclear protein extracts. Protein expression of caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2, matrix metalloprotease 9 (MMP-9), NF-κB p65, I-κBα and β-actin were analyzed by Western blot analysis (Towbin et al. 1979; Al-Yahya et al. 2015). NF-κB DNA-binding assay was carried out using the Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (Al-Yahya et al. 2015).

Histopathological studies

Formalin (10%)-fixed heart tissue were embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned into 4–5 µm sections, deparaffinized, and rehydrated using standard techniques. The sections were then stained with H&E and examined for histological alterations.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and multiple comparisons were carried out using Dunnett’s test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Total phenolic and betalain contents in BRJ

The total phenolic and betalain levels in BRJ were 12.78 mg/g and 10.27 mg/g, respectively.

Phytochemical analysis of BRJ

BRJ was analyzed to determine the presence of betalains (betacyanins and betaxanthin); this analysis was carried out using the molecular weights obtained by the UPLC-ESI-MS analysis and by comparing the peaks in the UV spectra to data from the literature. The mass spectral data of the BRJ chemical constituents are presented according to their retention time in Table 1. By generating the mass spectra for the extract components in negative- and positive-ion modes, the molecular masses could be determined.

Table 1.

Mass spectral data (negative and positive detection) of beetroot juice

| Structure | m/z | Ions | Structure | m/z | Ions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclodopa glucoside | 356 | [M −H]− | Glucoside of dihydroxyindol | 192 | [M −H−glucose]− |

| 715 | [2M + H]+ | Carboxylic acid | 354 | [M −H]− | |

| N-Formylcyclodopa glucoside | 383 | [M −H]− | l-Tryptophan | 203 | [M −H]− |

| 385 | [M + H]+ | 409 | [2M + H]+ | ||

| Vulgaxanthin I | 338 | [M −H]− | Isobetanin | 549 | [M −H]− |

| 677 | [2M −H]− | 551 | [M + H]+ | ||

| 340 | [M + H]+ | Neobetanin | 547 | [M −H]− | |

| Vulgaxanthin II | 339 | [M −H]− | 549 | [M + H]+ | |

| 341 | [M + H]+ | p-Coumaric acid | 163 | [M −H]− | |

| Indicaxanthin 307 | 307 | [M −H]− | 327 | [2M −H]″ | |

| Betalamic acid 210 | 210 | [M −H]− | 165 | [M + H]+ | |

| 212 | [M + H]+ | Ferulic acid | 195 | [M −H]+ | |

| Betanin | 549 | [M −H]− | |||

| 551 | [M + H]+ |

Acute toxicity and pilot study

Mortality was not observed in the limit test at the 2000 mg/kg dose, but the BRJ doses, 150 and 300 mg/kg/day (i.g.), were optimal for functional recovery of cardiac markers (data not shown).

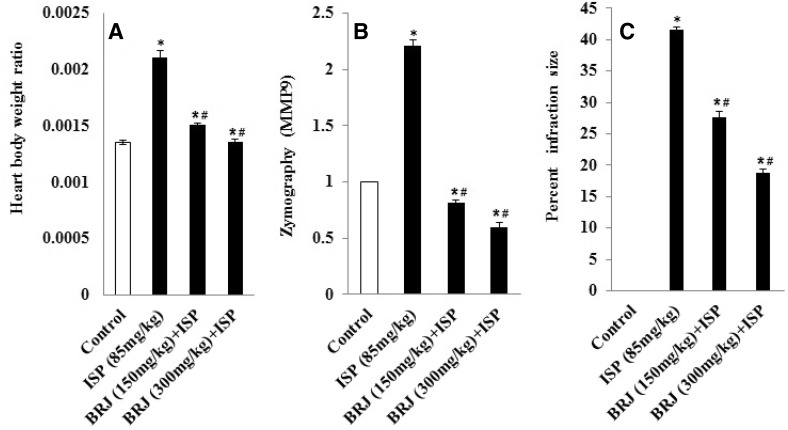

Heart weight to body weight ratio

Although BRJ-pretreated rats had a significantly reduced cardiac weight index when compared to the ISP-treated rats, the latter had a significantly (P < 0.05) greater cardiac weight to body weight index than normal rats (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of BRJ on a heart weight to body weight ratio, b MMP-9 activity as determined by zymography, and c myocardial infarction size (percent of control) in experimental rats. The results are presented as mean ± SEM with six animals per group. *Denotes significant differences compared to the control group (P < 0.05); #denotes significant differences compared to the ISP group (P < 0.05)

Serum biomarkers

To determine the cardioprotective effect of BRJ in ISP-administered rats, we determined the levels of serum biomarkers. ISP significantly increased serum AST, ALT, GGT, ALP, LDH, and CK-MB, but pretreatment with BRJ (150 or 300 mg/kg) significantly reduced these levels, indicating that BRJ attenuates ISP-induced tissue injuries in vivo (Table 2). We also determined the activity of BRJ on lipid metabolism by measuring the levels of serum lipoproteins. ISP administration stimulated an upsurge in the serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C, and VLDL-C, and a decline in HDL-C. BRJ significantly downregulated these effects in a dose-dependent manner (Table 3), demonstrating that BRJ has a substantial restoration effect on ISP-induced variation in the serum lipid profile of rats.

Table 2.

Effect of BRJ on serum marker enzymes in control and experimental rats

| Enzyme | Control | ISP (85 mg/kg) | BRJ (150 mg/kg) + ISP | BRJ (300 mg/kg) + ISP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST (U/L) | 73.92 ± 0.95 | 155.01 ± 2.47* | 133.96 ± 2.12*# | 92.15 ± 1.40*,# |

| ALT (U/L) | 26.89 ± 0.82 | 106.68 ± 1.15* | 89.80 ± 1.78*,# | 52.15 ± 1.54*,# |

| ALP (U/L) | 273.75 ± 6.19 | 451.83 ± 16.23* | 340.84 ± 3.98*,# | 286.03 ± 8.72*,# |

| LDH (U/L) | 86.85 ± 0.92 | 185.43 ± 1.64* | 146.32 ± 1.65*,# | 127.08 ± 1.56*,# |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 139.04 ± 2.12 | 194.74 ± 1.78* | 181.97 ± 3.07*,# | 146.27 ± 3.41*,# |

| GGT (U/L) | 5.39 ± 0.10 | 11.37 ± 0.39* | 9.40 ± 0.44*,# | 7.04 ± 0.42*,# |

The results are presented as mean ± SEM with six animals per group

*Significant differences compared to the control group (P < 0.05)

#Significant differences compared to the ISP group (P < 0.05)

Table 3.

Effect of BRJ on the serum lipid profile in control and experimental rats

| Group | Cholesterol | Triglycerides | HDL-C | LDL-C | VLDL-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 91.9 ± 3.67 | 73.5 ± 3.40 | 55.08 ± 3.16 | 22.13 ± 3.55 | 14.71 ± 0.68 |

| ISP (85 mg/kg) | 198.5 ± 4.26* | 153.9 ± 3.90* | 28.46 ± 1.87* | 139.25 ± 5.80* | 30.78 ± 0.78* |

| BRJ (150 mg/kg) + ISP | 164.3 ± 5.49*,# | 130 ± 2.86*,# | 41 ± 2.92*,# | 97.33 ± 8.55*,# | 26 ± 0.57*,# |

| BRJ (300 mg/kg) + ISP | 127.3 ± 2.61*,# | 107.03 ± 3.33*,# | 41.41 ± 3.56*,# | 64.51 ± 5.53*,# | 21.40 ± 0.66*,# |

The results are presented as mean ± SEM with six animals per group

*Significant differences compared to the control group (P < 0.05)

#Significant differences compared to the ISP group (P < 0.05)

Antioxidant and oxidative stress markers

The redox enzyme activities of SOD, CAT, NP-SH and NO were significantly depleted in the heart of ISP-induced rats compared to normal rats (Table 4). BRJ pretreatment (150 or 300 mg/kg) of ISP-challenged rats significantly increased the levels of SOD, CAT, NP-SH and NO (all P < 0.01). Furthermore, ISP-challenged rats had significantly enhanced levels of MDA and myeloperoxidase (MPO), which are markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in the heart tissue (Table 4). Pretreating ISP-challenged rats with BRJ (150 or 300 mg/kg) significantly reduced these levels in a dose-dependent manner (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of BRJ on the antioxidant and oxidative stress markers in the control and experimental rats

| Marker | Control | ISP (85 mg/kg) | BRJ (150 mg/kg) + ISP | BRJ (300 mg/kg) + ISP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPO (U/mg protein) | 4.51 ± 0.20 | 20.39 ± 0.87* | 10.96 ± 0.57*# | 7.97 ± 0.33*# |

| CAT (U/mg protein) | 48.78 ± 1.23 | 18.05 ± 1.06* | 27.99 ± 0.37*,# | 38.26 ± 1.26*,# |

| NO (U/mg protein) | 37.85 ± 1.25 | 15.44 ± 0.77* | 24.89 ± 1.63*,# | 21.12 ± 1.67*,# |

| SOD (U/mg protein) | 10.01 ± 0.53 | 4.12 ± 0.21* | 5.70 ± 0.14*,# | 7.91 ± 0.51*,# |

| MDA (nmol/g) | 0.66 ± 0.11 | 10.50 ± 0.82* | 4.41 ± 0.48*# | 2.35 ± 0.18*,# |

| Total protein (g/L) | 115.73 ± 4.10 | 40.88 ± 1.23* | 52.09 ± 1.70*,# | 72.96 ± 4.46*,# |

| NP-SH (nmol/g) | 7.04 ± 0.50 | 3.36 ± 0.29* | 3.95 ± 0.33*,# | 5.18 ± 0.32*,# |

The results are presented as mean ± SEM with six animals per group

*Significant differences compared to the control group (P < 0.05)

#Significant differences compared to the ISP group (P < 0.05)

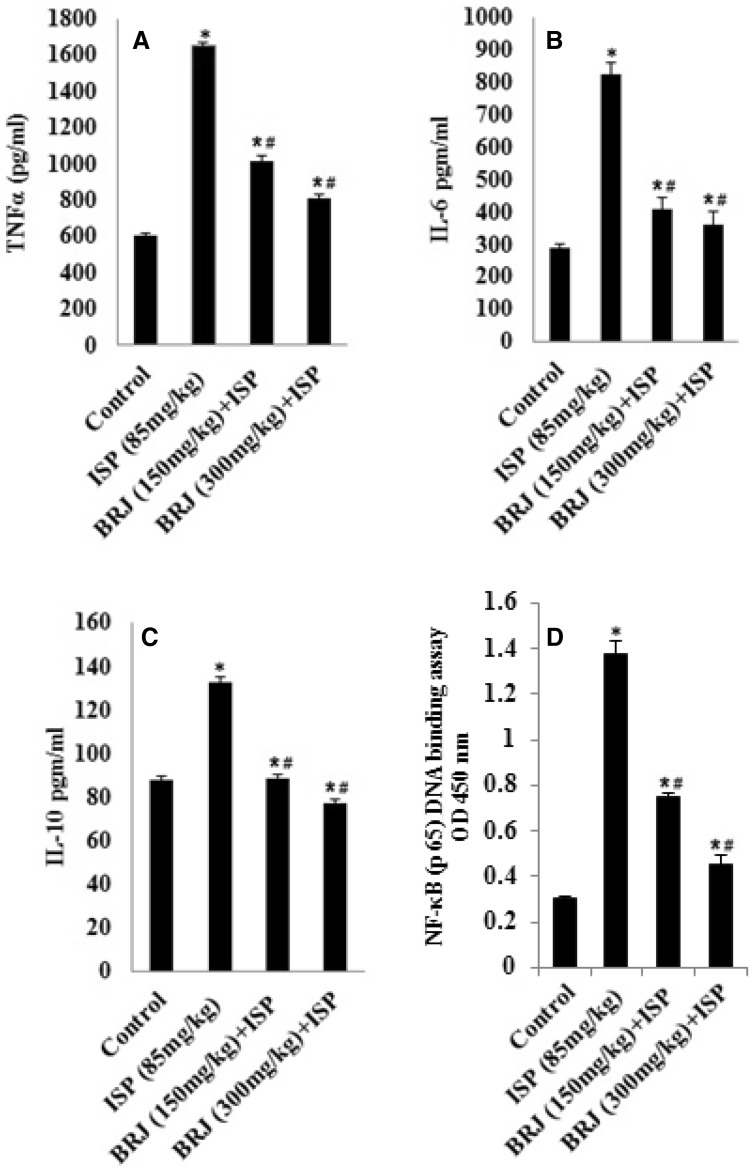

Inflammatory cytokine levels and NF-κB DNA binding

In exploring the pathway implicated in the cardioprotective effects of BRJ, we found that the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 were significantly elevated in the cardiac tissues of ISP-challenged rats compared to normal rats. Administering BRJ (150 or 300 mg/kg) prior to ISP administration significantly reduced these levels in a dose-dependent manner (all p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Additionally, ISP significantly increased NF-κB DNA-binding activity (Fig. 4, upper panel) compared to that in normal (control) rats, but BRJ pretreatment at 150 or 300 mg/kg significantly reduced the DNA-binding activity compared to ISP treatment alone.

Fig. 2.

Effect of BRJ on the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 and NF-κB DNA binding) in control and experimental rats. The results are presented as mean ± SEM with six animals per group. *Denotes significant differences compared to the control group (P < 0.05); #denotes significant differences compared to the ISP group (P < 0.05)

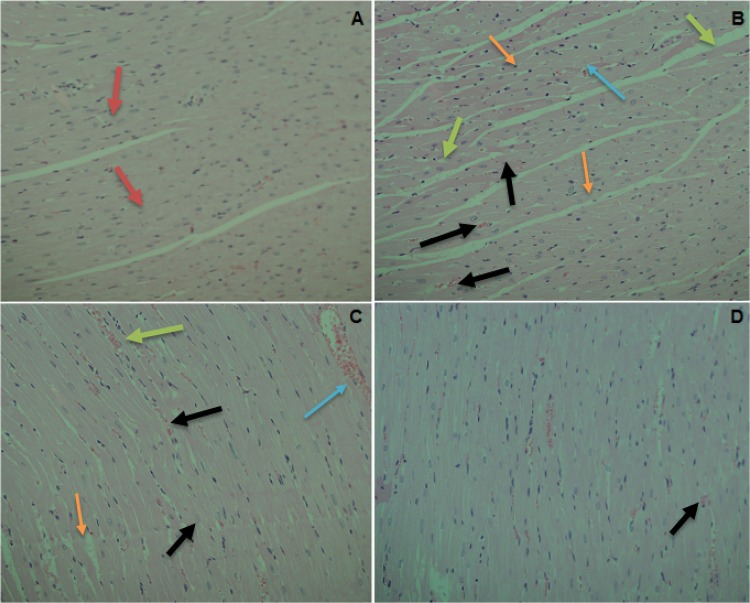

Fig. 4.

Effect of BRJ pretreatment on the histopathological changes in cardiac tissue of ISP-treated rats. Photomicrographs of the myocardium tissue in a normal rats (group I) exhibiting normal cardiomyofibril architecture (red arrow). b ISP-inflicted rats (group II) exhibiting perivascular cuffing (green arrow) of vasa vasorum with intimal fibrosis, disruption of medial elastic fibers with diffuse interstitial fibrosis, myocytolysis (orange arrow) and myonecrosis (blue arrow). c BRJ (150 mg/kg bodyweight) + ISP-treated rats (group III) showing decreased degree of myonecrosis (black arrow) and less infiltration of inflammatory cells, and d BRJ (300 mg/kg body weight) + ISP-inflicted rats demonstrate restoration of myocardial damage in terms of declined degree of necrosis and minor infiltration of inflammatory cells. Heart tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and visualized under a light microscope at × 100 magnification

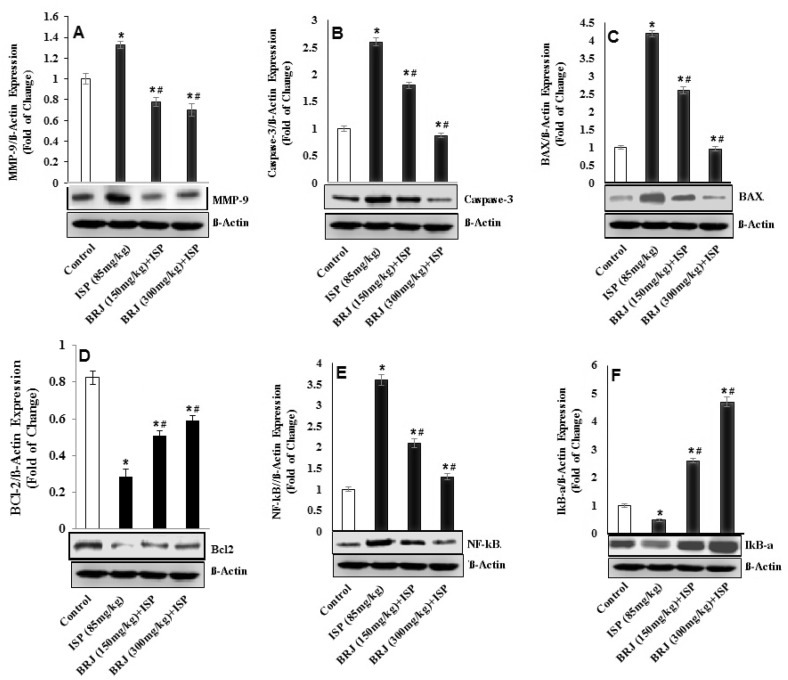

Suppression of myocardial apoptotic and MMP-9 protein expression

ISP-challenged rats had significantly increased cardiac expression of Bax and caspase-3 proteins and significantly reduced Bcl-2 protein expression compared to the expression in normal rats. Pretreating ISP-intoxicated rats with BRJ (150 or 300 mg/kg) effectively reduced the cardiac expression of Bax and caspase-3 and upregulated the Bcl-2 protein level (Fig. 3). MMP-9 activity in the cardiac tissue was determined by immunoblotting. Compared to normal rats, there was an enhanced expression of MMP-9 in ISP-treated rats, but BRJ pretreatment dose dependently reversed this enhancement.

Fig. 3.

Effect of BRJ on MMP9, caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2, NF-κB and IκB-ɑ protein expression in control and experimental rats. The results are presented as mean ± SEM with six animals per group. *Denotes significant differences compared to the control group (P < 0.05); #denotes significant differences compared to the ISP group (P < 0.05)

Free radical scavenging activity of BRJ

BRJ exhibited a rather suitable ROS scavenging effect in vitro (Table 5), as it was able to stably reduce DPPH to the yellow-colored DPPH-H; this occurred at high concentrations (500 and 1000 µg/mL) only.

Table 5.

In vitro free radical scavenging activity of BRJ

| Tested substance | Radical scavenging activity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 µg/mL | 100 µg/mL | 500 µg/mL | 1000 µg/mL | |

| BRJ | 39.83 | 59.37 | 78.93 | 87.81 |

| Ascorbic acid | 70.91 | 91.51 | 93.80 | 96.23 |

Histological improvement of injured myocardial tissues by BRJ

Histological examination of cardiac tissue showed that ISP caused inflammation, which led to several alterations in the structure of the myocardium such as infiltration of cells and cell extravasation. Other structural alterations observed in the ISP-challenged group include interstitial edema with vacuoles (Fig. 4). BRJ pretreatment alleviated these ISP-induced inflammatory changes in cardiac cells, demonstrating that BRJ effectively attenuates morphological changes caused by ISP in cardiac tissue.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that the use of antioxidants can limit infarct size, lessen myocardial dysfunction, and decelerate the advancement and reduce the consequences of MI (Agrawal et al. 2014). Our in vivo study showed an elevated cardiac index in ISP-challenged rats. The gain in heart weight might be attributed to the increased volume of water in the interstitial space due to edema (Upaganlawar et al. 2009). A 1% increase in water content in the myocardium may lead to a 10% loss in cardiac efficiency (Laine and Allen 1991). As beetroot is a good source of antioxidants, consuming this vegetable root may serve as a tool to strengthen antioxidant defenses to protect cells from oxidative stress and maintain cellular redox balance. BRJ was estimated to possess total phenolic and betalain levels of 12.78 mg/g and 10.27 mg/g, respectively. In addition, the UPLC-ESI mass spectral data revealed the presence of betalain, isobetalain, vulgaxanthin, neobetanin, p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid, aligned with the previous findings of Wybraniec et al. (2005); these researchers reported that betalain and isobetalain are the main phytoconstituents of beetroot. In our study, BRJ exhibited potent ROS scavenging effects in vitro, further supporting the proposal that BRJ has potent antioxidant and free radical scavenging effects (Wybraniec 2005; Tesoriere et al. 2008).

BRJ pretreatment led to the amelioration of markers of cardiac function, and structural alterations in ISP-treated rats. The substantial decline in CK-MB and LDH levels due to this pretreatment emphasizes the in vivo cardioprotective effects of BRJ. Redox enzymes (e.g., glutathione, SOD and CAT) are necessary to curb oxidative stress as they remove free ROS and produce OH radicals (Sawyer et al. 2002). The present in vivo results showed that BRJ restored redox enzymes in the myocardium, since the reductions in SOD and CAT activities, and NP-SH content in the ISP-treated group were significantly reversed by the BRJ treatment. Lipid peroxidation plays a substantial role in myocardial necrosis (Lord-Fontaine and Averill-Bates 2002). As BRJ diminishes the elevation in MDA level in ISP-challenged rats, this supports the concept that the potent antioxidant activities of BRJ underlie its cardio-protective properties. Several reports have shown that beetroot contains various antioxidants (El Gamal et al. 2014; Georgiev et al. 2010), which supports the theory that BRJ reduces the LPO caused by ISP. MPO is biomarker of MI (Asselbergs et al. 2004) and pretreatment with BRJ significantly alleviated its enhancement, suggesting that BRJ reduces cellular infiltration into the heart. The serum lipid profile of BRJ-administered rats showed significantly boosted HDL-C with decreased cholesterol and triglyceride levels, which are in accordance with previous findings (Joris and Mensink 2013; Al-Yahya et al. 2015). Increased serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL nurture the progression of atherosclerosis. ISP is known to elevate the concentrations of serum lipids, which in turn leads to cardiac tissue damage (Chilton 2004). Based on these observations, we can speculate that treatment with BRJ might reduce the risk of cardiac diseases in humans. BRJ contains a high concentration of inorganic nitrate, which may be converted to NO in vivo, and this occurrence has important vascular and metabolic consequences (Hobbs et al. 2013). In our study, BRJ pretreatment significantly reduced the decline in NO observed in ISP-treated rats. Numerous reports have demonstrated that ISP prompts the discharge of cytokines in the myocardium (Kaptoge et al. 2014). Inhibiting cytokine production is therefore a good approach to curb MI (Seropian et al. 2014). We observed an elevation in TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 levels in the myocardium of ISP-challenged rats compared to normal rats, but pretreating the challenged rats with BRJ (150 or 300 mg/kg) significantly and dose dependently suppressed these levels. TNF-α is presumed to play a crucial role in apoptosis, and promotes myocardial injury. The enhanced expression of caspase-3 and Bax, and reduced expression of Bcl-2 in ISP-challenged rats point to the apoptotic injuries caused by ISP.

The above data suggest that pretreatment with BRJ (150 and 300 mg/kg) may alleviate inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis, thereby providing an effective approach against ISP-induced MI. BRJ pretreatment (150 and 300 mg/kg) dose dependently suppressed NF-κB (p65) and significantly repressed NF-κB activation, but increased IκBα, an NF-κB transcription factor that regulates inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and iNOS) in the cytosol. NF-κB is activated after cardiac injury, and cardiac myocytes and interstitial cells are important sources of NF-κB (Hirotani et al. 2002; Lawrence 2009; Raish 2017). BRJ pretreatment (150 and 300 mg/kg) in ISP-intoxicated animals enhanced the level of serum cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10), NF-κB, and NF-κB DNA-binding activity when compared to normal rats. Pretreatment with BRJ in rats with ISP-induced MI significantly and dose dependently reduced NF-κB protein expression and NF-κB DNA-binding activity compared to normal rats. These results further corroborate earlier studies and offer the comprehensive mechanism underlying NF-κB activation by ROS, and its role in the development and progression of myocardial necrosis and hypertrophy (Sahu et al. 2014; Maulik and Kumar 2012; Moris et al. 2017; Frantz et al. 2001). MMPs are released by endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, myocardial cells, and other cells, and are dependent on Ca2+ and Zn2+ (Du et al. 2015).

Our study showed that BRJ pretreatment significantly suppressed MMP-9 activity in ISP-treated rats. Extracellular matrix degradation by MMPs has been implicated in CVDs such as cardiomyopathy, atherosclerosis, and MI (Kim et al. 2000). MMP-9 expression was selected for analysis, as it serves as a proximal biomarker of cardiac remodeling and a distal biomarker of inflammation. The triggered expression of MMP-9 at the transcriptional level by TNF-α has also been reported (Li et al. 2007). ISP caused inflammatory lesions in the cardiac tissue of rats, which led to various structural alterations in the myocardium, penetration of neutrophils and extravasation of red blood cells. BRJ pretreatment mitigated these ISP-induced inflammatory alterations in the heart tissue, indicating that BRJ pretreatment substantially and dose dependently attenuates morphological changes caused by ISP in the cardiac tissue.

Conclusion

This investigation provides experimental data to support the role of BRJ in restoring myocardial function after ISP-induced cardiotoxicity. Thus, BRJ can be used as a valuable cardioprotective agent to suppress oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis via MMP-9 inhibition. Together, the data of present study provide evidence that BRJ is an outstanding source of antioxidants that provides chemoprotection to cellular damage from oxidation in vitro and importantly, in vivo. The consumption of BRJ might be a promising adjunct strategy to help manage cardiovascular diseases propagated by oxidative stress, such as cardiac injuries. Therefore, it should be considered that application of a beetroot juice helps as a useful model to provide insight into the efficacy of beetroot juice as an antioxidant agent. Further studies in humans are warranted to examine the clinical relevance of such observations.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the Research Group Number, RG-1438-081.

Abbreviations

- BRJ

Beetroot juice

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- ISP

Isoproterenol

- b.w

Body weight

- LPO

Lipid peroxidation

- AST

Aspartate transaminase

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- CK-MB

Creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- TP

Total protein

- CAT

Catalase

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- NP-SH

Non-protein sulphydydryl group

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- OD

Optical density

- s.c

Sub-cutaneous

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa B

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aebi H. ) Catalase. Methods in enzymatic analysis. Cheime: Academic; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal YO, Sharma PK, Shrivastava B, Ojha S, Upadhya HM, Arya DS, Goyal SN. Hesperidin produces cardioprotective activity via PPAR-gamma pathway in ischemic heart disease model in diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yahya M, Raish M, AlSaid MS, Ahmad A, Mothana RA, Al-Sohaibani M, Al-Dosari MS, Parvez MK, Rafatullah S. ‘Ajwa’ dates (Phoenix dactylifera L.) extract ameliorates isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy through downregulation of oxidative, inflammatory and apoptotic molecules in rodent model. Phytomedicine. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselbergs FW, Tervaert JW, Tio RA. Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(5):516–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200401293500519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann G. A fully enzymatic colorimetric determination of HDL-cholesterol in the serum. Internist. 1979;20:559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton RJ. Pathophysiology of coronary heart disease: a brief review. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104(9 Suppl 7):S5–S8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KJ, O’Brien KA, Tanner RJ, Polkey JI, Minnion M, Feelisch M, Polkey MI, Edwards LM, Hopkinson NS. Acute dietary nitrate supplementation and exercise performance in COPD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised controlled pilot study. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Hao J, Liu F, Lu J, Yang X. Apigenin attenuates acute myocardial infarction of rats via the inhibitions of matrix metalloprotease-9 and inflammatory reactions. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(6):8854–8859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Gamal AA, AlSaid MS, Raish M, Al-Sohaibani M, Al-Massarani SM, Ahmad A, Hefnawy M, Al-Yahya M, Basoudan OA, Rafatullah S. Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) extract ameliorates gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity associated oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in rodent model. Mediat Inflamm. 2014;2014:983952. doi: 10.1155/2014/983952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Chen M, Fang X, Lau WB, Xue L, Zhao L, Zhang H, Liang YH, Bai X, Niu HY, Ye J, Chen Q, Yang X, Liu M. Aging might augment reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and affect reactive nitrogen species (RNS) level after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in both humans and rats. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(4):1017–1026. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S, Kelly RA, Bourcier T. Role of TLR-2 in the activation of nuclear factor kappaB by oxidative stress in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(7):5197–5203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev VG, Weber J, Kneschke EM, Denev PN, Bley T, Pavlov AI. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of betalain extracts from intact plants and hairy root cultures of the red beetroot Beta vulgaris cv. Detroit dark red. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2010;65(2):105–111. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281(5381):1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotani S, Otsu K, Nishida K, Higuchi Y, Morita T, Nakayama H, Yamaguchi O, Mano T, Matsumura Y, Ueno H, Tada M, Hori M. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in G-protein-coupled receptor agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circulation. 2002;105(4):509–515. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs DA, George TW, Lovegrove JA. The effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure and endothelial function: a review of human intervention studies. Nutr Res Rev. 2013;26(2):210–222. doi: 10.1017/S0954422413000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PJ, Mensink RP. Beetroot juice improves in overweight and slightly obese men postprandial endothelial function after consumption of a mixed meal. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeris T, Bao Y, Korthuis RJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: a double edged sword in ischemia/reperfusion vs preconditioning. Redox Biol. 2014;2:702–714. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptoge S, Seshasai SR, Gao P, Freitag DF, Butterworth AS, Borglykke A, Di Angelantonio E, Gudnason V, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Jorgensen T, Danesh J. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(9):578–589. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HE, Dalal SS, Young E, Legato MJ, Weisfeldt ML, D’Armiento J. Disruption of the myocardial extracellular matrix leads to cardiac dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(7):857–866. doi: 10.1172/JCI8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala TS, Vienola MS, Klika KD, Loponen JM, Pihlaja K. Betalain and phenolic compositions of four beetroot (Beta vulgaris) cultivars. Eur Food Res Technol. 2002;214(6):505–510. doi: 10.1007/s00217-001-0478-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laine G, Allen S. Left ventricular myocardial edema. Lymph flow, interstitial fibrosis, and cardiac function. Circ Res. 1991;68(6):1713–1721. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.68.6.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappa B pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2009;1(6):a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Wettasinghe M, Bolling BW, Ji LL, Parkin KL. Betalains, phase II enzyme-inducing components from red beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) extracts. Nutr Cancer. 2005;53(1):91–103. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5301_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liang J, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA, Olson EN, Liu Z-P. FoxO4 regulates tumor necrosis factor alpha-directed smooth muscle cell migration by activating matrix metalloproteinase 9 gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(7):2676–2686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01748-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord-Fontaine S, Averill-Bates DA. Heat shock inactivates cellular antioxidant defenses against hydrogen peroxide: protection by glucose. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32(8):752–765. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00769-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(2):156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik SK, Kumar S. Oxidative stress and cardiac hypertrophy: a review. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2012;22(5):359–366. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2012.666650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moris D, Spartalis M, Tzatzaki E, Spartalis E, Karachaliou GS, Triantafyllis AS, Karaolanis GI, Tsilimigras DI, Theocharis S. The role of reactive oxygen species in myocardial redox signaling and regulation. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(16):324. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.06.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oecd . OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals. Paris: Organization for Economic; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha S, Golechha M, Kumari S, Arya DS. Protective effect of Emblica officinalis (amla) on isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2012;28(5):399–411. doi: 10.1177/0748233711413798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. A microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1) Clin Chim Acta. 2000;293(1–2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raish M. Momordica charantia polysaccharides ameliorate oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, inflammation, and apoptosis during myocardial infarction by inhibiting the NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;97:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rona G, Kahn DS, Chappel CI. Studies on infarct-like myocardial necrosis produced by isoproterenol: a review. Rev Can Biol. 1963;22:241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu BD, Putcha UK, Kuncha M, Rachamalla SS, Sistla R. Carnosic acid promotes myocardial antioxidant response and prevents isoproterenol-induced myocardial oxidative stress and apoptosis in mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;394(1–2):163–176. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer DB, Siwik DA, Xiao L, Pimentel DR, Singh K, Colucci WS. Role of oxidative stress in myocardial hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(4):379–388. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal Biochem. 1968;25:192–205. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seropian IM, Toldo S, Van Tassell BW, Abbate A. Anti-inflammatory strategies for ventricular remodeling following ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(16):1593–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299C:152–178. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spodick DH. Decreased recognition of the post-myocardial infarction (Dressler) syndrome in the postinfarct setting: does it masquerade as “idiopathic pericarditis” following silent infarcts? Chest. 2004;126(5):1410–1411. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesoriere L, Fazzari M, Angileri F, Gentile C, Livrea MA. In vitro digestion of betalainic foods. Stability and bioaccessibility of betaxanthins and betacyanins and antioxidative potential of food digesta. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(22):10487–10492. doi: 10.1021/jf8017172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upaganlawar A, Gandhi C, Balaraman R. Effect of green tea and vitamin E combination in isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction in rats. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2009;64(1):75–80. doi: 10.1007/s11130-008-0105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vali L, Stefanovits-Banyai E, Szentmihalyi K, Febel H, Sardi E, Lugasi A, Kocsis I, Blazovics A. Liver-protecting effects of table beet (Beta vulgaris var. rubra) during ischemia-reperfusion. Nutrition. 2007;23(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vleet J, Ferrans V, Herman E. Cardiovascular and skeletal muscle systems. Handb Toxicol Pathol. 2002;2:363–455. doi: 10.1016/B978-012330215-1/50036-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vulic JJ, Cebovic TN, Canadanovic-Brunet JM, Cetkovic GS, Canadanovic VM, Djilas SM, Saponjac VTT. In vivo and in vitro antioxidant effects of beetroot pomace extracts. J Funct Foods. 2014;6:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler BWC, Schroecksnadel K, Schennach H, Fuchs D. In vitro effects of beet root juice on stimulated and unstimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Am J Biochem Biotechnol. 2005;1:180–185. doi: 10.3844/ajbbsp.2005.180.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wybraniec S. Formation of decarboxylated betacyanins in heated purified betacyanin fractions from red beet root (Beta vulgaris L.) monitored by LC-MS/MS. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(9):3483–3487. doi: 10.1021/jf048088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Xu Q, Zheng P, Yan L, Zheng J, Dai G. Cardioprotective effect of fluvastatin on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;586(1–3):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]