Abstract

Background

Efficacy of telmisartan in treating hypertension (HT) in cats has not been largely investigated.

Objective

Telmisartan oral solution effectively controls systolic arterial blood pressure (SABP) in hypertensive cats.

Animals

Two‐hundred eighty‐five client‐owned cats with systemic HT.

Methods

Prospective, multicenter, placebo‐controlled, randomized, double‐blinded study. Hypertensive cats diagnosed with SABP ≥160 mmHg and ≤200 mmHg without target‐organ‐damage were randomized (2 : 1 ratio) to receive 2 mg/kg telmisartan or placebo q24 PO. A 28‐day efficacy phase was followed by a 120‐day extended use phase. Efficacy was defined as significant difference in mean SABP reduction between telmisartan and placebo on Day 14 and group mean reduction in SABP of > 20 mmHg by telmisartan on Day 28 compared to baseline.

Results

Two‐hundred fifty‐two cats completed the efficacy and 144 cats the extended use phases. Mean SABP reduction at Day 14 differed significantly between groups (P < .001). Telmisartan reduced baseline SABP of 179 mmHg by 19.2 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 15.92‐22.52) and 24.6 (95% CI: 21.11‐28.14) mmHg at Days 14 and 28. The placebo group baseline SABP of 177 mmHg was reduced by 9.0 (95% CI: 5.30‐12.80) and 11.4 (95% CI: 7.94‐14.95) mmHg, respectively. Of note, 52% of telmisartan‐treated cats had SABP <150 mmHg at Day 28. Mean SABP reduction by telmisartan in severe (≥180 mmHg) and moderate HT (160‐179 mmHg) was comparable and persistent over time.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Telmisartan solution (PO) was effective in reducing SABP in hypertensive cats with SABP ≥160 mmHg and ≤200 mmHg.

Keywords: angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), feline hypertension, systolic arterial blood pressure (SABP), telmisartan

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- ACEi

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- AE

adverse event

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- AT1

angiotensin‐II type 1 receptor

- AT2

angiotensin‐II type 2 receptor

- AT‐II

angiotensin‐II

- CI

confidence interval

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- HT

hypertension

- ITT

intention to treat

- LOCF

last observation carried forward

- PPS

per protocol set

- RAAS

renin angiotensin aldosterone system

- SABP

systolic arterial blood pressure

- SAF

safety

- T4

thyroxine

- TOD

target organ damage

1. INTRODUCTION

Blood pressure increases with age in cats and systemic hypertension (HT) and the associated target organ damage (TOD) are commonly recognized in elderly cats.1, 2 Ocular lesions occur in more than 40% of hypertensive cats.3 Additionally, systemic HT can cause damage to the brain, kidneys, and heart.4 Consequently, early recognition and management of systemic HT are crucial. The most common disease causing secondary systemic HT in cats is chronic kidney disease (CKD), followed by hyperthyroidism.4, 5 In about 20% of cats with systemic HT, however, no underlying disease is identified and thus are classified as idiopathic.5 The pathophysiology of systemic HT in cats is poorly understood. The renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) could play a role based on studies in small cohorts of cats with CKD and idiopathic HT and in cats with hyperthyroidism.6, 7 Chronic kidney disease‐related systemic HT is believed to be induced by the activation of the RAAS.7, 8 Angiotensin‐II is a central mediator of renal injury because of its ability to produce glomerular HT resulting in glomerular damage and activation of pro‐inflammatory and profibrotic pathways.9, 10 Chronic RAAS activation leads to persistent systemic HT via systemic vasoconstriction, intravascular fluid expansion, and sympathetic activation, mediated by the angiotensin‐II type 1 receptor (AT1 receptor).11 The direct inhibition of AT1 receptors with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) inhibits the activation of these receptors by multiple mediators, some of which are formed by pathways that do not involve conventional angiotensin converting enzymes (ACEs) and leave the angiotensin‐II type 2 receptor (AT2 receptors) available for activation.12 Angiotensin‐II type 2 receptors mediate beneficial actions of angiotensin‐II (AT‐II) such as vasodilation and natriuresis.13 The underlying mechanisms of systemic HT secondary to hyperthyroidism in cats remain to be determined, although dysfunction of the RAAS is suspected.7 Although the RAAS is implicated in cats with systemic HT of various cause, some cats do appear to have low renin HT. In human medicine, inhibition of the RAAS appears to benefit patients with low renin HT.14

Drugs that are used to treat systemic HT in cats include calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), beta‐blockers, and diuretics.8, 15, 16 However, so far, only the calcium channel blocker amlodipine lowers adequately systemic blood pressure,3, 17, 18 which is accompanied by activation of the RAAS system.6 Telmisartan is an AT‐II receptor antagonist which selectively binds to the AT1 receptor and thus inhibits the pro‐hypertensive effects of AT‐II including vasoconstriction, sodium chloride retention, vascular and cardiac muscle hypertrophy, and pro‐fibrotic effects in the kidney and cardiovascular systems.19 In human medicine, telmisartan is authorized for the control of systemic HT and cardiovascular prevention.19, 20, 21 In experimental models, telmisartan effectively inhibits angiotensin‐induced pressure responses of cats at doses of 1‐3 mg/kg.22

In cats with CKD, telmisartan at the dose of 1 mg/kg PO q24h proved to be an effective antiproteinuric drug, significantly reducing proteinuria relative to baseline at all assessment points.23 The goal of the present field study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of telmisartan at reducing systemic HT in cats.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

Client‐owned, adult, cats presented during routine clinical practice at the participating 51 centers from Germany, France, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Switzerland were screened for systemic HT. Cats of either sex were eligible for inclusion if owner informed consent was given and the cats complied with all inclusion and exclusion criteria. Diagnosis of systemic HT was based on a systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg by Doppler methodology (Parks Non Directional Ultrasonic Doppler Device Type 811B) on 2 separate screening visits according to ACVIM guidelines.4 Only trained operators predefined at each institution made blood pressure measurements. Baseline systolic arterial blood pressure (SABP) was defined as the mean of the SABP measurements at the 2 screening visits where SABP at each visit was calculated as the arithmetic mean of 3 measurements for each animal.

Eligible cats were categorized according to the concurrent diseases that might cause systemic HT using the following criteria. Diagnosis of CKD was in accordance with the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines24 based on urine specific gravity <1.035 in combination with evidence of CKD, that is, present or documented serum creatinine ≥1.6 mg/dL or irregular, small kidneys on palpation, abnormal findings during ultrasound or radiographic examination. Hyperthyroidism was based on history of clinical signs of hyperthyroidism with increased thyroxine (total T4) concentration above the laboratory reference interval. Hyperthyroidism had to be successfully controlled for >4 weeks as confirmed by a T4 concentration ≤60 nmol/L at screening visits 14 or 2 days before study inclusion. Cats fulfilling both, criteria for systemic HT with CKD and hyperthyroidism, were classified as having both diseases. Cats were classified as idiopathic HT if systemic HT was not associated with CKD or hyperthyroidism (controlled or uncontrolled).4

Cats were ineligible for inclusion if they had received medications known to affect blood pressure, such as ACEi, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, or diuretics <14 days before start of treatment.

Cats were excluded if SABP was >200 mmHg at both screening visits, SAPB measurements were highly variable in the individual cat with differences of >20% on 3 consecutive blood pressure measurements at 1 visit, or they had acute or severe TOD, total T4 concentration > 60 nmol/L, were pregnant, or were lactating. Acute or severe TOD was defined by the presence of retinopathy/choroidopathy (acute blindness, retinal detachment, or retinal/vitreal hemorrhage), signs of hypertensive encephalopathy such as seizures, or other centrally localizing neurological signs of acute onset. Furthermore, cats were excluded, if azotemia was related to acute kidney injury or decompensated CKD or to known pre‐ or post‐renal factors or to considerable risk for the cat not to complete the entire study period. Furthermore, cats with confirmed or suspected concomitant diseases such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, or neoplasia were ineligible.

2.2. Study design

This multicenter prospective, randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled study with parallel group design was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice principles.25

The study consisted of a 28 day efficacy phase and a subsequent 92‐day extended use phase.

Physical examination, fundoscopy, and SABP measurement were performed before inclusion and on study days 14, 28, 56, 84, and 120. Blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and serum tubes and sent to Vet Med Labor GmbH (Germany) before the start of study and on study days 28 and 120. Urine was collected by cystocentesis and analyzed by the same laboratory before inclusion.

During the efficacy phase, cats were randomly assigned at a rate of 2 : 1 to telmisartan oral solution at a dosage of 2 mg/kg or an optical identical oral placebo once daily. This treatment dose was chosen based on the results of a previous study.26 The randomization was performed using a covariate‐adaptive randomization procedure with the focus on achieving an approximate ratio of 2 : 1 for telmisartan and placebo with respect to the 2 stratifying factors “classification of hypertension” and “study site,” while also including a random component.27 In every randomization step, the current imbalance from the expected 2 : 1 ratio was determined for each of the stratifying factors. This allocation scheme ensured an approximate treatment ratio of 2 : 1 for each site separately and for each HT class across sites.27

Dose reduction in 0.5 mg/kg increments to a minimum dose of 0.5 mg/kg was only allowed if signs of hypotension were observed in combination with an SABP <100 mmHg. Dose reduction was undertaken even in the absence of clinical signs of hypotension if SABP <80 mmHg. An increase of the dose was not permitted in the study protocol.

After Day 28, treatment was unmasked and cats treated with telmisartan were allowed to enter the extended use phase. During this phase, the telmisartan dose could be decreased at the discretion of the investigator if the cat's SABP was <160 mmHg. The target SABP range was defined as 120‐160 mmHg. Cats with SABP >200 mmHg were removed from the study and treated at the discretion of the attending clinician.

Routine treatments with no known impact on systemic HT (eg, vaccinations, antiparasitic drugs) were allowed during the study. Antiinflammatory drug treatment during the study was only permitted as short‐term (<14 days) treatment. The protocol was prepared in consultation with independent experts and approved by local authorities, when required. All adverse events (AEs) were reported in accordance with local regulations.

2.3. Statistical methods

A composite primary efficacy end point was defined a priori for the evaluation of telmisartan efficacy. The first co‐primary end point was the difference in mean SABP change from baseline to Day 14 between the telmisartan and placebo treatment group, which was tested by a 2‐sided 2‐sample Student's t test with alpha = 0.05 (SAS software, Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The null hypothesis of no difference in mean SABP change between telmisartan and placebo after 14 days treatment was tested for the per protocol set (PPS) population. The second co‐primary end point was clinically relevant mean SABP reduction for telmisartan, defined by a mean SABP decrease >20 mmHg between baseline SABP and SABP on study day 28. The ACVIM consensus statement defined the goal of systemic HT treatment of cats as achieving a reduction in the category of risk for future TOD.4 The primary end point criterion that the mean SABP reduction should be ≥20 mmHg fulfilled this goal completely, because it assured that the risk of the included cat group for future TOD is reduced by at least 1 category on Day 28 compared to baseline after the ACVIM HT consensus statement.

For animals excluded from the study on study day 14 or thereafter due to SABP >200 mmHg or development of acute or severe TOD, missing SABP data were imputed on the subsequent visits using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method, imputing the last observed SABP from the same animal.

A sample size calculation was performed by simulations using the SAS software (version 9.3, SAS Institute) and calculated as the number of animals required to successfully achieve both co‐primary end points. The original assumptions of the sample size calculation were reviewed within an a priori planned interim analysis. In the latter, only the required number of animals was provided to prevent any potential unblinding. This sample size calculation indicated that 294 cats were required to evaluate the efficacy of telmisartan over placebo (ratio telmisartan/placebo 2 : 1) with alpha = 0.05, a power of 80%, 10% dropouts without LOCF data available, and using the following assumptions for effect and variability estimates: mean telmisartan SABP change = −24 mmHg (SD = 23.7 mmHg), mean placebo SABP change = −16 mmHg (SD = 20.6 mmHg).

Additional analyses were performed by scheduled study visits and treatment using descriptive statistics: subgroup analysis on mean SABP reduction, frequency of animals with SABP according to IRIS TOD categorization or >15% decrease compared to baseline SABP, frequency of animals with SABP reduction of >20 mmHg, mean SABP reduction according to SABP at baseline, and change in telmisartan dose. The 1st co‐primary end point was assessed also for SABP reduction from baseline at Day 28. Uncertainty of the treatment effects was measured using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The proportions of cats with minimal risk of TOD and the proportions of cats with SABP reduction >20 mmHg were compared for Day 28 between groups using chi‐square tests. The proportions of telmisartan‐treated cats with minimal risk of TOD was compared between Days 14 and 28 using chi‐square test.

The efficacy of study treatments was assessed on the basis of the PPS population. This group comprised all study animals having reached at least study day 14. Cases of relevant deviations from the protocol (eg, enrollment of cat although exclusion criterion was fulfilled) and cases not subjected to all the relevant assessments (eg, study protocol was not followed due to owner's noncompliance) were not included in the PPS. The intention to treat (ITT) population included cats that had at least 1 documented dose of telmisartan or placebo administered, at least 1 analyzable data parameter available, and major entry criteria were satisfied. The safety (SAF) population included all cats that had received at least 1 dose of telmisartan or placebo. The SAF population was used for the analysis of AEs, which were reported by the participating veterinarians and for the analysis of clinicopathologic data. Incidence of AEs was summarized descriptively by treatment groups and the proportions of cats that experienced at least 1 AE were compared between groups by a chi‐square test.

3. RESULTS

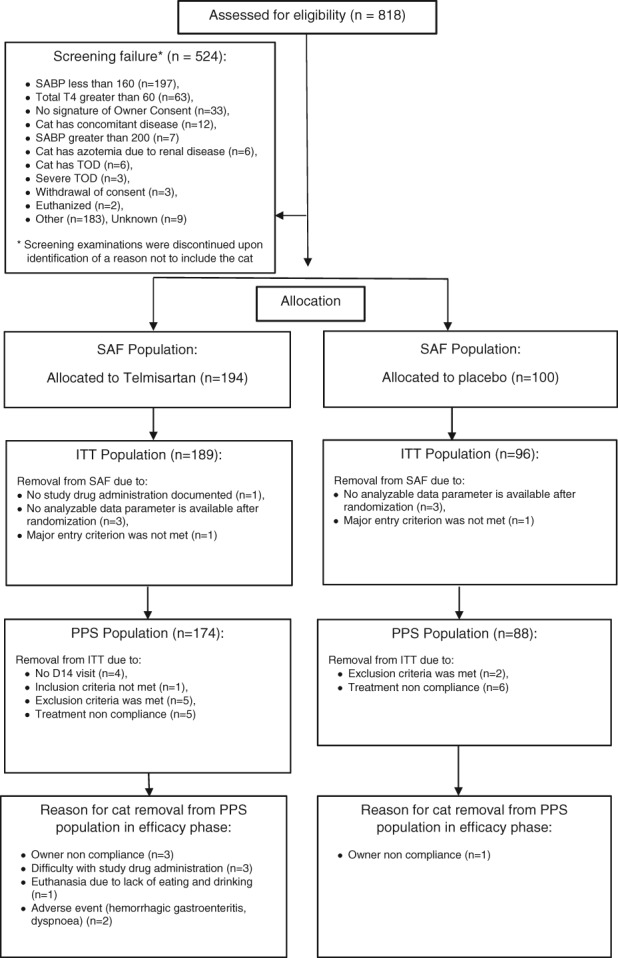

Out of 818 documented screened cats, a total of 294 cats were enrolled, on average 6 cats per site, and included in the SAF data set (Figure 1). Of those, 285 formed the ITT population and 262 cats comprised the PPS. The end of the placebo controlled study phase (Day 28) was reached by 165 telmisartan‐treated cats and 87 placebo‐treated cats. One placebo‐ and 2 telmisartan‐treated cats were removed from the study before Day 28 due to SABP >200 mmHg according to the study protocol. For the efficacy analysis, however, their data were included using the LOCF method. By the end of an additional 2nd phase (Day 120) additional 21 cats had discontinued the study, due to lost to follow‐up (4 cats), AEs (3 cats: renal failure in 1 cat; hypersalivation in 1 cat; anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting, and renal failure in 1 cat), or withdrawal of owner consent (9 cats). Six cats were removed due to SABP >200 mmHg in this 2nd phase of the study. Age, body weight, breed distribution, causes of systemic HT, and baseline SABP were similar in both groups (Table 1). Males and females were not evenly distributed in both groups with more males in the placebo group. However, the mean reduction of SABP after 28 days was comparable between the neutered males and females in both treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Participant flow

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the telmisartan and placebo groups (ITT and PPS population)

| Variable | Telmisartan | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT (n = 189) | PPS (n = 174) | ITT (n = 96) | PPS (n = 88) | |

| Baseline SABP (mmHg): Mean (±SD) | 179.3 (±9.9) | 179.1 (±10.0) | 177.4 (±9.9) | 177.3 (±10.1) |

| Demographics | ||||

| Female: % (n) | 50.8 (96) | 48.9 (85) | 37.5 (36) | 38.6 (34) |

| Male: % (n) | 49.2 (93) | 51.1 (89) | 62.5 (60) | 61.4 (54) |

| Intact: % (n) | 4.2 (8) | 4.0 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Neutered/spayed: % (n) | 95.8 (181) | 96.0 (167) | 100.0 (96) | 100.0 (88) |

| Age (years): Mean (±SD) | 13.3 (±3.4) | 13.3 (±3.4) | 13.1 (±3.5) | 13.2 (±3.5) |

| Body weight (kg): Mean (±SD) | 4.4 (±1.2) | 4.4 (±1.2) | 4.5 (±1.3) | 4.5 (±1.4) |

| Breeda | ||||

| British %: (n) | 3.7 (7) | 3.4 (6) | 3.1 (3) | 3.4 (3) |

| Crossbreed %: (n) | 4.8 (9) | 5.2 (9) | 2.1 (2) | 2.3 (2) |

| Domestic short/long hair: % (n) | 76.7 (145) | 75.9 (132) | 80.2 (77) | 79.5 (70) |

| Persian %: (n) | 4.8 (9) | 5.2 (9) | 7.3 (7) | 8.0 (7) |

| Cause of hypertension | ||||

| CKD: % (n) | 30.2 (57) | 29.9 (52) | 31.3 (30) | 30.7 (27) |

| Hyperthyroidism: % (n) | 7.4 (14) | 7.5 (13) | 7.3 (7) | 8.0 (7) |

| CKD + hyperthyroidism: % (n) | 4.8 (9) | 4.6 (8) | 5.2 (5) | 5.7 (5) |

| Idiopathic: % (n) | 57.7 (109) | 58.0 (101) | 56.3 (54) | 55.7 (49) |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; ITT, intention to treat; PPS, per protocol set; SABP, systolic arterial blood pressure.

Breeds with frequency below 3% are not shown.

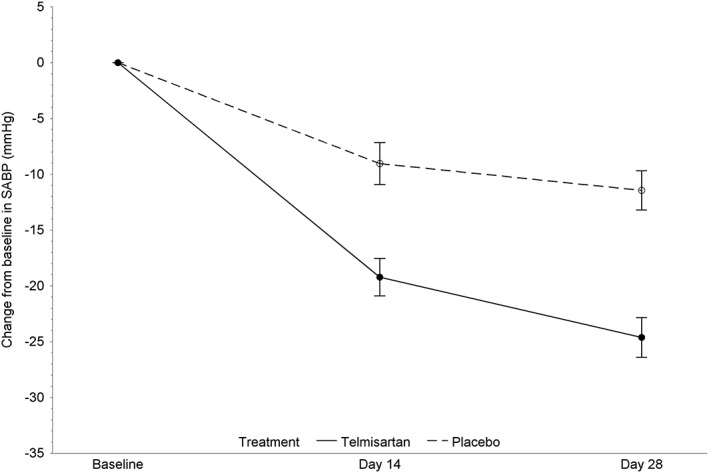

The primary analysis showed a significant difference in mean SABP change between the telmisartan and placebo groups on Day 14 (P < .001) and a clinically relevant mean telmisartan SABP reduction of 24.6 mmHg on Day 28; hence, both co‐primary end points were successfully achieved (Table 2, Figure 2). In order to check the primary analysis result for robustness, the testing procedure was reperformed for the ITT population as well. Both co‐primary end points were achieved in the ITT population with similar results (Table 2). The mean SABP reduction from baseline in the PPS population was 19.2 (95% CI: 15.92‐22.52) mmHg for the telmisartan group and 9.0 (95% CI: 5.30‐12.80) mmHg for the placebo group on Day 14, and 24.6 (95% CI: 21.11‐28.14) mmHg for the telmisartan group and 11.4 (95% CI: 7.94‐14.95) mmHg for the placebo group on Day 28. The difference in mean SABP change between the telmisartan and placebo groups was statistically significant on Day 28 (P < .001) as well. The mean reduction in SABP was not dependent on the concurrent disease or the presence of idiopathic HT, neither in the telmisartan nor in the placebo group. The proportion of cats with SABP reduction >20 mmHg on Day 28 was significantly different between groups (telmisartan: 55% [90/165 cats], placebo: 28% [24/87 cats], P < .001). By Day 28, the proportion of cats with a SABP <150 mmHg or >15% decrease compared to baseline SABP was significantly different between the groups (telmisartan: 52% [85/165 cats], placebo: 25% [22/87 cats], P < .001). Between Days 14 and 28, the proportion of telmisartan‐treated cats with an SABP <150 mmHg or >15% decrease compared to baseline SABP significantly increased (Day 14: 34% [60/174], Day 28: 52% [85/165]; P < .001).

Table 2.

Mean change in SABP (mmHg) in the telmisartan and placebo groups (PPS and ITT)

| Mean change of SABP (mmHg) | Telmisartan | Placebo | Primary analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPS population | |||

| On Day 14a | −19.2 | −9.0 | Comparison of mean |

| 95% CI | −22.52 to −15.92 | −12.80 to −5.30 | SABP reduction between |

| Number of cats (n) | n = 174 | n = 88 | groups: P < .001 |

| On Day 28a | −24.6 | −11.4 | Clinical relevance |

| 95% CI | −28.14 to −21.11 | −14.95 to −7.94 | defined as mean SABP |

| Number of cats (n) | n = 165 | n = 87 | reduction >20 mmHg |

| ITT population | |||

| On Day 14b | −19.2 | −8.8 | Comparison of mean |

| 95% CI | −22.4 to −16.0 | −12.4 to −5.3 | SABP reduction between |

| Number of cats (n) | n = 185 | n = 96 | groups: P < .001 |

| On Day 28b | −24.5 | −10.8 | Clinical relevance |

| 95% CI | −27.9 to −21.0 | −14.4 to −7.1 | defined as mean SABP |

| Number of cats (n) | n = 174 | n = 94 | reduction >20 mmHg |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ITT, intention to treat; PPS, per protocol set; SABP, systolic arterial blood pressure.

Baseline SABP (mmHg) mean (±SD): telmisartan: 179.1 (±9.9), placebo: 177.3 (±10.1).

Baseline SABP (mmHg) mean (±SD): telmisartan: 179.3 (±9.9), placebo: 177.4 (±9.9).

Figure 2.

Mean (95% confidence interval of the mean) changes from baseline in systolic arterial blood pressure during the blinded efficacy phase (per protocol set population)

In the 2nd phase of the study, the mean decrease in SABP from baseline in the telmisartan group was persistent over time on Days 56, 84, and 120 (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Mean SABP reduction compared to baseline and frequency of cats with SABP <150 mmHg or a ≥15% SABP decrease from baseline in the telmisartan group; frequency of cats with SABP change >20 mmHg compared to baseline in telmisartan and placebo groups (PPS population)

| Visit | Change of SABP from baseline (mmHg) mean (±SD) (n) | Percentage of cats with SABP < 150 mmHg or an SABP decrease from baseline ≥15% (n) | Percentage of cats with SABP change >20 mmHg compared to baseline in the telmisartan group | Percentage of cats with SABP change >20 mmHg compared to baseline in the placebo group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 14 | −19.2 (±22.1) (n = 174) | 34.5 (60) | 42.5 (74) | 27.3 (24) |

| Day 28 | −24.6 (±22.9) (n = 165) | 51.5 (85) | 54.5 (90) | 27.6 (24) |

| Day 56 | −26.9 (±24.0) (n = 152) | 56.5 (86) | 63.2 (96) | NA |

| Day 84 | −26.5 (±25.2) (n = 148) | 57.4 (85) | 61.5 (91) | NA |

| Day 120 | −27.6 (±26.9) (n = 144) | 60.4 (87) | 66.7 (96) | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PPS, per protocol set; SABP, systolic arterial blood pressure.

Table 4.

Frequency of cats in SAPB categories according to IRIS TOD categorization (PPS population)

| Telmisartan | Placebo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Percentage of cats with SABP in the following range (n) | Sample size | Percentage of cats with SABP in the following range (n) | |||||||

| <150 mmHga | ≥150 mmHg and <160 mmHg | ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg | ≥180 mmHg | <150 mmHga | ≥150 mmHg and <160 mmHg | ≥160 mmHg and <180 mmHg | ≥180 mmHg | |||

| Day 14 | 174 | 34.5 (60) | 12.6 (22) | 32.8 (57) | 20.1 (35) | 88 | 25 (22) | 5.7 (5) | 31.8 (28) | 37.5 (33) |

| Day 28 | 165 | 51.5 (85) | 10.3 (17) | 23.0 (38) | 15.2 (25) | 87 | 25.3 (22) | 14.9 (13) | 31 (27) | 28.7 (25) |

| Day 56 | 152 | 56.6 (86) | 14.5 (22) | 13.8 (21) | 15.1 (23) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Day 84 | 148 | 57.4 (85) | 8.8 (13) | 18.9 (28) | 14.9 (22) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Day 120 | 144 | 60.4 (87) | 8.3 (12) | 15.3 (22) | 16 (23) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: IRIS, International Renal Interest Society; NA, not applicable; PPS, per protocol set; SABP, systolic arterial blood pressure; TOD, target organ damage.

or SABP decrease from baseline ≥15%.

The mean reduction in SABP in the telmisartan group in the severely hypertensive category (≥180 mmHg) was comparable to those with moderate systemic HT (160‐179 mmHg) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean SABP reduction over time compared to baseline in the telmisartan and placebo groups in cats with SABP at baseline between 160 and 179 mmHg and 180 and 200 mmHg (PPS population)

| SABP at baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between 160 and 179 mmHg | Between 180 and 200 mmHg | |||

| Telmisartan baseline SABP mean: 171.9 mmHg (n = 98) | Placebo baseline SABP mean: 170.9 mmHg (n = 56) | Telmisartan baseline SABP mean: 188.4 mmHg (n = 76) | Placebo baseline SABP mean: 188.5 mmHg (n = 32) | |

| Visit | Mean SABP reduction compared to baseline at respective visit (mmHg) | |||

| Day 14 | 16.7 (n = 98) | 8.8 (n = 56) | 22.3 (n = 76) | 9.5 (n = 32) |

| Day 28 | 22.9 (n = 94) | 11.9 (n = 55) | 26.6 (n = 71) | 10.9 (n = 32) |

| Day 56 | 24.7 (n = 87) | NA | 29.6 (n = 65) | NA |

| Day 84 | 23.2 (n = 85) | NA | 30.7 (n = 63) | NA |

| Day 120 | 23.5 (n = 81) | NA | 32.9 (n = 63) | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PPS, per protocol set; SABP, systolic arterial blood pressure.

The starting telmisartan dose of 2 mg/kg PO q24 was administered to all cats in the efficacy phase of the study. The majority of cats were continued on this dose (112/143 cats; 78%), whereas some cats (31/143 cats; 22%) were down titrated to a dose of 1.5 mg/kg or lower.

No clinically relevant changes in routine hematological and biochemical parameters at study end compared to baseline were observed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Laboratory variables of telmisartan‐ and placebo‐treated cats at baseline, on Days 28 and 120 (SAF population)

| Variable (SD) | Telmisartan (n=194a) | Placebo (n=100a) | Reference range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Day 28 | Day 120 | Baseline | Day 28 | ||

| Erythrocytes (T/L): Mean (±SD) | 8.58 (±1.48) | 8.21 (±1.58) | 8.28 (±1.67) | 8.41 (±1.57) | 8.52 (±1.52) | 5‐10 T/L |

| PCV (%) mean (±SD) | 40.1 (±6.1) | 37.9 (±6.3) | 38.7 (±6.3) | 38.7 (±7.2) | 38.9 (±6.2) | 28%‐45% |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) mean (±SD) | 1.74 (±0.81) | 1.73 (±0.75) | 1.72 (±0.68) | 1.66 (±0.72) | 1.63 (±0.66) | <1.9 mg/dL |

| BUN (mmol/L) mean (±SD) | 12.96 (±5.68) | 12.92 (±4.69) | 13.12 (±5.13) | 12.44 (±5.57) | 12.89 (±6.01) | 5.7‐13.5 mmoL/L |

| Potassium (mmol/L) mean (±SD) | 4.50 (±0.55) | 4.53 (±0.58) | 4.47 (±0.54) | 4.54 (±0.49) | 4.51 (±0.49) | 3.3‐5.8 mmoL/L |

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; SAF, safety.

Sample size of listed variables might be lower.

The proportion of cats with at least 1 AE during the efficacy phase was similar in both groups (telmisartan: 30% [58/194 cats], placebo: 29% [29/100 cats], P = .89). Overall, the incidence of cats with at least 1 AE was low in the efficacy phase (Table 7). The frequency of cats with at least 1 AE was comparable or lower in the extended use phase compared to the above‐mentioned frequencies in the efficacy phase. Hypotension was observed at 1% (2/194 cats) of the telmisartan‐treated cats in the efficacy phase and also at 1% (2/194 cats) of the cats in the extended use phase. No hypotension was observed in the placebo group.

Table 7.

Overview of adverse events with incidence ≥2% during the efficacy phase (safety population)

| Adverse event | Percentage of cats (number of cats) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Telmisartan (n = 194) | Placebo (n = 100) | Overall (n = 294) | |

| All adverse events | 29.9 (58) | 29.0 (29) | 29.6 (87) |

| Emesis | 6.2 (12) | 6.0 (6) | 6.1 (18) |

| Hypertension | 2.6 (5) | 4.0 (4) | 3.1 (9) |

| Anorexia | 3.6 (7) | 1.0 (1) | 2.7 (8) |

| Diarrhea | 2.1 (4) | 3.0 (3) | 2.4 (7) |

| Tachycardia | 3.1 (6) | 1.0 (1) | 2.4 (7) |

4. DISCUSSION

In this large clinical field study, it was demonstrated that telmisartan lowers the mean SABP in cats with systemic HT compared to placebo, controls SABP over time and is well tolerated.

In the cats of this study, representing patients as seen by veterinarians in daily practice, mean reduction of SABP was significantly different between the telmisartan and placebo groups on Day 14 and the mean reduction in response to telmisartan was deemed clinically relevant as the mean SABP decreased by more than 20 mmHg in the telmisartan group by Day 28. The effect on lowering mean SABP and the proportion of cats with SABP <150 mmHg to minimize TOD4, 28 increased between Days 14 and 28 without an increase of the dose, and the antihypertensive effect was persistent over the 120‐day study duration. This observation was reconfirmed by the results obtained after repeating the analysis without those cats that dropped out during the study with a high blood pressure. This finding is similar to those in human patients, in which it is known that after the first dose of telmisartan, the antihypertensive activity gradually becomes evident within 3 hours, and the maximum reduction in blood pressure is generally attained 4‐8 weeks after the start of treatment and is sustained during long‐term treatment.21 The observed mean SABP reduction in the telmisartan group was in line with the assumption based on the interim analysis. The assumption regarding the mean SABP change in the placebo group based on the interim analysis was somewhat higher compared to the result of the study. This discrepancy in placebo effect estimates might be related to the lower number of available cats in the placebo group at the time the interim analysis was performed due to the 2 : 1 randomization ratio.

Although, the role of the RAAS in systemic HT of cats is not fully understood, the results of the present study suggest that activation of the RAAS might be involved in the pathogenesis, as systemic HT could be successfully controlled, independent of the underlying disease or idiopathic HT. The relative lack of efficacy of ACE inhibitors (ACEis) in treating systemic HT in cats observed by others8, 15, 16, 29 could be explained by the use of an inadequate dosage, inadequate conversion of angiotensinogen into AT1 receptor agonists without the involvement of conventional ACE. An alternative explanation might be the fact that ARBs leave the AT2 receptor effects of AT‐II intact.

The mean SABP decrease in placebo‐treated cats of around 10 mmHg on Day 14, which persisted until Day 28, had been also observed in a previous study.18 This might be due to a training effect regarding the procedure of measuring blood pressure, respectively the fading of a white coat effect over time.30 Another potential hypothesis, although less likely, might be a true placebo effect, resulting from either how the veterinarian approached the blood pressure measurement process or how the owners treated the cat. Whatever the reason, this finding illustrates the importance of including a placebo group for blood pressure trials in veterinary medicine.

Telmisartan at a starting dose of 2 mg/kg PO q24h was well tolerated and safe to use in this study of cats with HT, as was found previously when telmisartan was used at half this dose in a group of elderly cats with CKD.23 Generally medications targeting the RAAS, such as ACEis, or ARBs might induce a decline in glomerular filtration rate particularly in cases with late stage kidney disease or in dehydrated animals with CKD and regular monitoring according to good clinical practice is deemed appropriate. However, there was no increase in mean serum creatinine in cats treated with telmisartan in this study, even in the subgroup of cats with IRIS stage 2 and 3 CKD.

There are some differences between the present study and the previous randomized controlled clinical trial involving the use of amlodipine in hypertensive cats that are worthwhile mentioning. One is that SABP in the present study was measured by Doppler compared to high‐definition oscillometry in a previous study.18 The Doppler methodology was chosen as at the start of the study it was the most commonly used method by practitioners and none of the available methods had been fully validated according to the ACVIM consensus statement criteria. Another difference in the studies was the criteria to define a responder. In the present study, the mean SABP reduction in the telmisartan group had to be both, significantly different compared to placebo at Day 14 and to be higher than 20 mmHg compared to baseline at Day 28. The criteria in a previous study were decrease of SABP to <150 mmHg or decrease from baseline of at least 15%.18 In the previous study, the dosage of amlodipine was doubled at Day 14 in 54% of the cats due to nonresponse at the starting dose, which was not allowed in the present study; higher doses of telmisartan could have increased the number of responders in the present study. Another difference is that cats receiving ACEi were ineligible for inclusion in the present study, whereas in a previous study 15.6% of the enrolled cats were on concomitant ACEi treatment.18

Common causes of systemic HT in the present study were CKD, hyperthyroidism, and a combination of the 2. This was not unexpected, because these are the most common reported causes of systemic HT in cats, and therefore such cats are specifically screened.4 However, the percentage of cats with idiopathic HT seemed to be relatively high in comparison to previous publications reporting 17%‐23% of the investigated cats having idiopathic HT.5, 31, 32 One explanation for this finding might be the definitions of CKD and hyperthyroidism. In the present study, CKD was diagnosed if the cat had urine specific gravity below 1.035 combined with plasma creatinine above 1.6 mg/dL or abnormal kidneys on palpation or on ultrasound or on radiographic examination. Euthyroidism was defined as serum total T4 < 60 μmol/L; however, hyperthyroidism might already be present at a T4 > 40 μmol/L.7 Another reason might be whitecoat HT contributing to the placebo effect, which might be present in an unknown number of cats enrolled in this study. Furthermore, there are relatively few studies in the literature documenting the prevalence of HT in cats, and most publications are biased toward screening only those populations of cats that are deemed to be at risk. In the present study, by contrast, not only cats at risk of HT because of the underlying concomitant diseases were screened but a more general cat population. Although, there might have been differences among the selection of screened cats at each study center, the high number of participating study sites resulted in a overall group of screened cats, which reflected a more general cat population. Thus, it is entirely possible that more idiopathic hypertensive cats were recruited to the present study because cats registered with primary care practitioners were screened more widely for HT than in previous studies. Even if the percentage of idiopathic HT is overestimated in this study, it nevertheless supports previous reports in which idiopathic HT was a common finding in cats.3, 31, 32 Overall, regular screening of adult cats for systemic HT, particularly aiming to prevent TOD as recommended in recent systemic HT guidelines28 is supported by this study as reflected in the high number of cats with increased blood pressure in the screened group.

The observed AEs were attributed to concurrent medical conditions and not associated with telmisartan administration. Due to the mode of action of telmisartan, transient hypotension might occur, although it was observed at a very low rate throughout the study. Symptomatic treatment, for example, fluid treatment, should be provided in case of any clinical signs of hypotension.

A limitation of the present study was the exclusion of cats with SABP above 200 mmHg (ie, cats with most severe systemic HT and highest risk of TOD) as it was considered unethical to enroll such cats where the risk of TOD appears to be extremely high into a placebo‐controlled study. In accordance, the primary end point criterion that the mean SABP reduction should be ≥20 mmHg would not necessarily lead to a reduction in the category of risk for future TOD if cats with SABP above 200 mmHg would have been included. Nevertheless, it is expected that telmisartan would efficiently lower SABP also in these cats based on the observation in the present study as SABP was as effectively controlled as in cats with less severe systemic HT. In a recent published case report of a severely hypertensive cat, telmisartan as monotherapy effectively controlled blood pressure, whereas benazepril as monotherapy was unsuccessful after amlodipine had to be withdrawn due to development of gingival hyperplasia.33 Further limitations such as excluding cats with severe CKD from the study, the relatively high number of cats classified as idiopathic HT or whitecoat HT contributing to the placebo effect, have been discussed in more detail above.

Future studies are warranted to determine the optimal dose required to meet the target posttreatment blood pressure in cats with pretreatment blood pressure in excess of 200 mmHg.

In summary, telmisartan oral solution at 2 mg/kg q24h proved to lower SABP by a clinically relevant magnitude and duration in the absence of significant treatment‐related AEs. Thus, telmisartan is a valuable option for the treatment of systemic HT in cats.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This project was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, a company representative read and approved the final draft. Balazs Albrecht is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Esther Herberich is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG and Tanja Zimmering is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health GmbH.

Prof. Elliott has acted as a paid independent consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH providing advice on the study design and critically evaluating the results of the study for registration purposes. He is also a Consultant for Bayer Ltd., Ceva Animal Health, Elanco Animal Health, Kindred Bio Ltd, Orion Ltd., Vetoquinol Ltd., Waltham Centre for Pet Nutrition and Idexx Laboratories. He is a member of International Renal Interest Society sponsored by Elanco Animal Health Ltd. He received grant funding from Royal Canin Ltd., Elanco Animal Health, Ceva Animal Health.

Prof. Glaus has acted as a paid independent consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, he received speaker honoraria as well as his travel and accommodation was covered or reimbursed.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

The study was approved by the national responsible authority in Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, and Switzerland. In addition, it was approved by the animal welfare officer of the Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following veterinarians for their contributions and support: Christel Delprat, Nicolas Delamarche, Félix Pradies, Peggy Binaut, Laurent Bourdenx, Isabelle Papadopulo, Nicolas Mourlan, Caroline Zoller, Vincent Mahé, Frank Düring, Bernhard Sörensen, Wolfgang Paulenz, Peter Hettling, Sven Stahlhut, Götz Eichhorn, Robert Höpfner, Andreas Kirsch, André Mischke, Anja Ripken, Thomas Frank, Angelika Drensler, Angela Friedrich, Charlotte Trede, Uwe Urban, Birgit Lieser, Jennifer Rohloff, Barbara Hellwig, Kai‐Uwe Schuricht, André Schneider, Ira Marxen, Ulrike Beckereit, Bernhard Wehming, Kathrin Gliesche, Evert‐Jan De Boer, Emil Visnjaric, Babette Ravensbergen, Talitha Grotens, Alan Kovacevic, Thomas Baumgartner, Martha Cannon, Mark Evans, Chris Little, Sarah Middleton, Amanda Nicholls, Miranda Wright, Simon Backshall, Ellie Mardell, Simon Pope, Lorna Cook, Vivien Davison.

The authors also thank the following study team members for the preparation, conduct, and completion of the study: Bärbel Assmann, Silke Haag‐Diergarten, Sabrina Hartung, Theda Janssen‐Stump, Petra Marshall, Sina Marsilio, Nicole Mohren, Andreas Mühlhäuser, Hanns Walter Müller, Katja Kawohl, Saskia Kley, Katharina Krause, Marcus Popp, Julia Rose, Marcella von Salis, Ulrike Sent, Sabine Volbon, Daniel Wachtlin, Sabine Wirsch.

The authors are particularly grateful to the owners of the enrolled cats, who made this study possible.

Part of the study was published in abstract form at the 27th ECVIM‐CA Congress in Malta, 14th to 16th of September 2017: Glaus AM, Elliott J, Albrecht B. Efficacy of telmisartan in hypertensive cats: results of a large European clinical trial. Research Communications of the 27th ECVIM‐CA Congress, J Vet Intern Med 2017, 53.

Glaus TM, Elliott J, Herberich E, Zimmering T, Albrecht B. Efficacy of long‐term oral telmisartan treatment in cats with hypertension: Results of a prospective European clinical trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:413–422. 10.1111/jvim.15394

Funding information Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH

REFERENCES

- 1. Bijsmans ES, Jepson RE, Chang YM, Syme HM, Elliott J. Changes in systolic blood pressure over time in healthy cats and cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:855‐861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Payne JR, Brodbelt DC, Luis Fuentes V. Blood pressure measurements in 780 apparently healthy cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31:15‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jepson RE, Elliott J, Brodbelt D, Syme HM. Effect of control of systolic blood pressure on survival in cats with systemic hypertension. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:402‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown S, Atkins C, Bagley R, et al. Guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and management of systemic hypertension in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:542‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jepson RE. Feline systemic hypertension: classification and pathogenesis. J Feline Med Surg. 2011;13:25‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jepson RE, Syme HM, Elliott J. Plasma renin activity and aldosterone concentrations in hypertensive cats with and without azotemia and in response to treatment with amlodipine besylate. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28:144‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams TL, Elliott J, Syme HM. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system activity in hyperthyroid cats with and without concurrent hypertension. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:522‐529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steele JL, Henik RA, Stepien RL. Effects of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition on plasma aldosterone concentration, plasma renin activity, and blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive cats with chronic renal disease. Vet Ther. 2002;3:157‐166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ruster C, Wolf G. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system and progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2985‐2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitani S, Yabuki A, Taniguchi K, Yamato O. Association between the intrarenal renin‐angiotensin system and renal injury in chronic kidney disease of dogs and cats. J Vet Med Sci. 2013;75:127‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415‐472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Putnam K, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Cassis LA. The renin‐angiotensin system: a target of and contributor to dyslipidemias, altered glucose homeostasis, and hypertension of the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1219‐H1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kemp BA, Howell NL, Keller SR, Gildea JJ, Padia SH, Carey RM. AT2 receptor activation prevents sodium retention and reduces blood pressure in angiotensin II‐dependent hypertension. Circ Res. 2016;119:532‐543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Te Riet L, van Esch JH, Roks AJ, et al. Hypertension: renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system alterations. Circ Res. 2015;116:960‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Littman MP. Spontaneous systemic hypertension in 24 cats. J Vet Intern Med. 1994;8:79‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jensen J, Henik RA, Brownfield M, Armstrong J. Plasma renin activity and angiotensin I and aldosterone concentrations in cats with hypertension associated with chronic renal disease. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:535‐540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henik RA, Snyder PS, Volk LM. Treatment of systemic hypertension in cats with amlodipine besylate. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1997;33:226‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huhtinen M, Derre G, Renoldi HJ, et al. Randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trial of a chewable formulation of amlodipine for the treatment of hypertension in client‐owned cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:786‐793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hernandez‐Hernandez R, Sosa‐Canache B, Velasco M, et al. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists role in arterial hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(Suppl 1):S93‐S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Destro M, Cagnoni F, Dognini GP, et al. Telmisartan: just an antihypertensive agent? A literature review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:2719‐2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. European public assessment report of Micardis [Internet]. Summary of product characteristics; 2018. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/000209/WC500027641.pdf.

- 22. Jenkins TL, Coleman AE, Schmiedt CW, Brown SA. Attenuation of the pressor response to exogenous angiotensin by angiotensin receptor blockers and benazepril hydrochloride in clinically normal cats. Am J Vet Res. 2015;76:807‐813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sent U, Gossl R, Elliott J, et al. Comparison of efficacy of long‐term oral treatment with telmisartan and benazepril in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:1479‐1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. International Renal Interest Society [Internet] . IRIS staging of CKD; 2018. Available from: http://www.iris-kidney.com/guidelines/staging.html.

- 25. FDA‐CVM . Guidance for Industry #85; Good Clinical Practice—VICH GL9. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coleman AE, Brown SA, Stark M, et al. Evaluation of orally administered telmisartan for the reduction of indirect systolic arterial blood pressure in awake, clinically normal cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2018; 10.1177/1098612x18761439. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103‐115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taylor SS, Sparkes AH, Briscoe K, et al. ISFM consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of hypertension in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2017;19:288‐303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brown SA, Brown CA, Jacobs G, Stiles J, Hendi RS, Wilson S. Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor benazepril in cats with induced renal insufficiency. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:375‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schellenberg S, Glaus TM, Reusch CE. Effect of long‐term adaptation on indirect measurements of systolic blood pressure in conscious untrained beagles. Vet Rec. 2007;161:418‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maggio F, DeFrancesco TC, Atkins CE, et al. Ocular lesions associated with systemic hypertension in cats: 69 cases (1985‐1998). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;217:695‐702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Elliott J, Barber PJ, Syme HM, Rawlings JM, Markwell PJ. Feline hypertension: clinical findings and response to antihypertensive treatment in 30 cases. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42:122‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Desmet L, van der Meer J. Antihypertensive treatment with telmisartan in a cat with amlodipine‐induced gingival hyperplasia. JFMS Open Rep. 2017;3:1–5; 2055116917745236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]