Abstract

Objective: Nonviable necrotic eschar is an impedance to wound healing and can ultimately lead to failure of soft tissue coverage in traumatic or high-risk wounds. Topical therapeutic agents can provide a less invasive management alternative to surgical debridement of eschar.

Approach: The case of a 40-year-old male with a traumatic right lower extremity amputation complicated by surgical incision ischemic eschar formation is reported. Honey-based salve with burdock leaf dressings was used to noninvasively manage eschar extending over the incision site. Images were obtained for 5 months of follow-up.

Results: Five-month follow-up demonstrated complete resolution of eschar and re-epithelialization of skin in the affected region.

Innovation: Honey-based salve with burdock leaf dressings shows promise for enhancing healing outcomes in traumatic wounds that develop nonviable eschar.

Conclusion: Surgical debridement of an amputation stump with large ischemic eschar was avoided with the use of honey-based salve with burdock leaf dressings.

Keywords: eschar treatment, biological therapeutic dressing, traumatic amputation

Kath M. Bogie, DPhil

Introduction

The severely mangled extremity is a challenging clinical problem for the treating surgeon that predisposes trauma survivors to substantial morbidity and loss of function.1–3 In the acute setting, patients often present with active hemorrhage through the mangled extremity and orthopedic injuries too severe for successful limb salvage to occur. When hemorrhage through a mangled extremity cannot be controlled, amputation is sometimes performed, with careful consideration for maintaining as much native limb as possible when appropriate. Amputation in these cases allows hemostasis to occur. Attention can then be focused on resuscitating the patient and treating any other associated but less severe injuries.

After amputation is performed, a series of challenges must be overcome. Open fractures and contamination of the initial injury predispose the patient to infection.4 In addition, the full extent of soft tissue injury is often difficult to ascertain in the immediate postoperative period after amputation. Barriers to successful healing of traumatic and surgical wounds in the setting of amputation are often encountered in the following days and weeks as the zone of injury declares itself, presenting as inadequate soft tissue flap perfusion, poor host nutrition, and soft tissue infection.5

When wound healing complications are encountered, the options available to the surgeon to improve the clinical outcome may be limited based on patient preference or the wound characteristics themselves.6 Surgical debridement and wound bed preparation followed by split thickness skin grafting or even more advanced flaps and grafts have been suggested to be the standard of care for definitive closure of acute and chronic wounds not amendable to primary closure. However, patients wish to avoid multiple trips to the operating theater and alternative wound management strategies should be considered.7–9 In these scenarios, effective nonsurgical strategies for mitigating traumatic wound complications are of keen interest to surgeons and their patients. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), hyperbaric oxygen, and enzymatic debridement are commonly used nonsurgical alternatives.10–12 Wet to dry dressings with antiseptic solutions such as Dakins or betadine are also used,13 although there is growing concern that they do not provide an appropriate moist wound healing environment.14

Both patients and surgeons may be interested in the alleviation of traumatic wound complications without recourse to further surgery. Reports of topical biological therapeutic agents have shown promise. Honey-based salves that have been utilized as a wound dressing for centuries have more recently been found to have demonstrable antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenic properties.15 Furthermore, honey has been shown to debride wound slough mechanically, penetrate biofilm, reduce wound pH (3.5–4), increase local oxygen release from hemoglobin, and even promote fibroblast infiltrate.16,17 Honey has been shown to promote tissue healing in a variety of settings, most notably burn wounds and dehisced surgical wound beds.18

All parts of the burdock plant (Acrtium lappa) are used in traditional medicine. The leaves in particular are thought to have antibacterial and antifungal properties.19 The Amish community has used a natural dressing comprising honey-based B&W Ointment™ (Holistic Acres, LLC, Newcomerstown, OH) and burdock leaves to treat burns and wounds.20 It has previously been reported as being a successful alternative treatment for traumatic wounds requiring skin grafts, particularly in children.21 The Amish Burn Group reported that B&W ointment and burdock leaf therapy almost totally alleviated the distress caused by changing burn wound dressings and appeared to be an acceptable alternative to conventional burn care.22 However, others found limited efficacy on in vivo testing and recommended caution in the use of this complementary topical therapeutic for burn wounds.23 A literature search on the use of honey-based B&W ointment and burdock leaves for complications of complex traumatic wounds other than burns revealed no prior reports. The current article presents a case report on the effective use of this honey-based biological therapeutic intervention on a complex traumatic crush wound with complications, specifically tissue necrosis and eschar development.

Clinical Problem Addressed

Nonviable necrotic eschar is an impedance to wound healing and can ultimately lead to failure of soft tissue coverage of a lower extremity amputation stump. When present, this eschar can create a mechanical blockade to wound epithelialization, prolong the inflammatory component of the wound-healing mechanism, and serve as a nidus for soft tissue infection. For these reasons, surgeons classically opt for sharp debridement of eschar and revision of a wound closure to include skin grafts or vascularized flaps. Efforts to identify less invasive strategies for managing this complication have yielded a number of alternative debridement techniques. In this report, we present a case study wherein honey was utilized in combination with burdock leaves to promote successful healing of a traumatic transfemoral amputation surgical wound complicated by tissue necrosis without the need for further surgical revision in a patient opposed to additional surgery.

Materials and Methods

A 40-year-old Amish male laborer's right leg was caught beneath a loaded wooden shipping pallet weighing > 275 kg, which had fallen from a height during a freight lift accident at his workplace. He sustained a traumatic amputation of his right leg at the level of the proximal tibia and an ipsilateral closed femoral shaft fracture (Fig. 1A, B). He presented to our level 1 trauma facility in extremis, actively exsanguinating from the injured limb. His leg was found to be pulseless below the level of his injuries, and he was unable to demonstrate distal neurologic function. He was taken emergently to the operating room for knee disarticulation and hemostasis of a popliteal arterial avulsion injury (Fig. 1C, D). After disarticulation had been performed and hemostasis was achieved, he underwent resuscitation using the massive transfusion protocol. The surgical wound was packed with sterile laps and an NPWT dressing was utilized to bolster the initial wound (Fig. 2A–D). In addition, he was placed in a long leg splint to initially immobilize his femoral shaft injury and enable soft tissue rest to minimize any further microtrauma to an already threatened extremity.

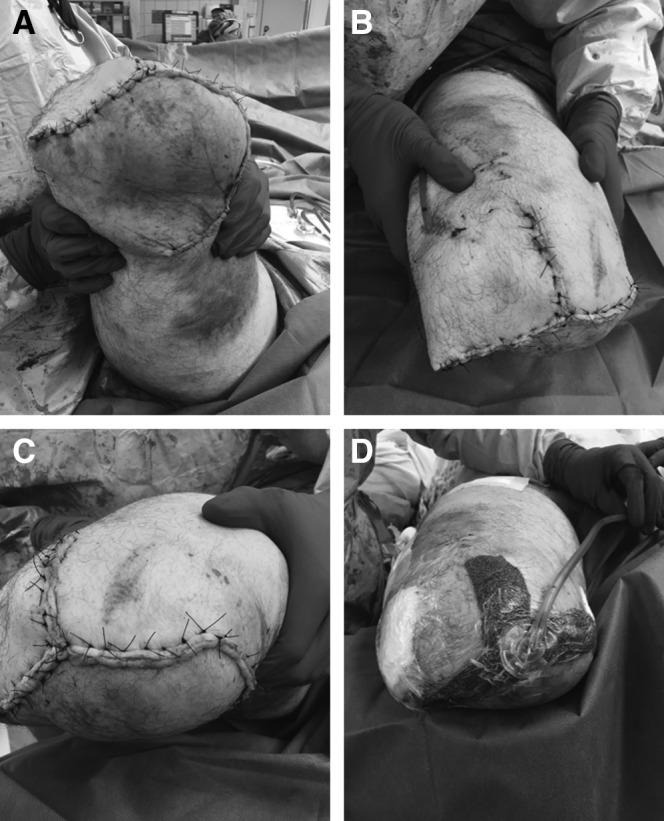

Figure 1.

Initial presentation of traumatic amputation. Injury X-ray (A) and clinical photo (B) demonstrating traumatic amputation. Postinitial debridement X-ray (C) with ipsilateral femur fracture and clinical photo (D) of remaining viable tissue.

Figure 2.

Clinical presentation after initial debridement of posterior flap. (A) Anterior repair and drain (B) and distal medial repair (C) with application of NPWT (D). NPWT, negative pressure wound therapy.

The following day he underwent revision amputation for definitive treatment of his extremity injury. The amputation was revised to above the knee using a Gritti–Stokes technique, with ipsilateral intramedullary fixation of the femoral shaft fracture using a retrograde femoral nail (Fig. 3A, B). The Gritti–Stokes method maintains the patella and quadriceps tendon by performing a patellofemoral arthrodesis. This allows for improvement in hip flexor strength and mobility of the amputation stump.24 Coverage of the distal femur was achieved using two anterior-based fasciocutaneous flaps of tissue from his thigh and a posterolateral-based fasciocutaneous flap advanced to the medial wound edge under tensionless closure. Intraoperatively, both anterior flaps appeared viable with bleeding wound edges, indicative of good perfusion. The posterior flap was the most traumatized and appeared to have questionable viability with less consistent perfusion to the edges; however, due to the fact that his posterior thigh would require very large graft if resected, it was utilized as a biological dressing in the acute setting to allow for formal zone of injury declaration. The incision was bolstered by reapplication of NPWT (Fig. 3C, D). The NPWT dressing was continued for 2 weeks postoperatively, and stump shrinker stockings were initiated on postoperative day 3 to maintain external support of the wound in lieu of a bulkier splint dressing but also to allow wound checks while in the hospital.

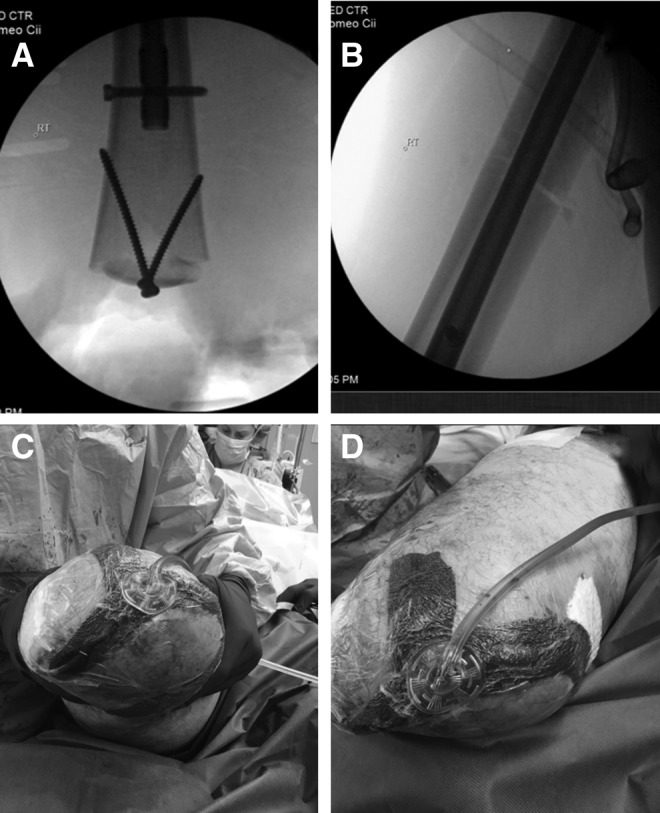

Figure 3.

Clinical status after Gritti–Stokes amputation. Arthrodesis of patella to the femoral stump (A) fracture reduction (B) and three-limbed flap (C) with application of NPWT (D).

The patient remained in the hospital and was maintained supine for 5 days postoperatively before discharge home. He was then followed with regular clinic visits at 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 weeks by the treating surgeon. At his first postoperative evaluation, there was a large area (∼30 × 12 cm) of skin pallor and tissue necrosis noted on the posterior medial soft tissue flap (Fig. 4A, B), which had been in the initial zone of injury and used for a local fasciocutaneous flap. This portion of the wound appeared nonviable and had started to form a thick eschar beginning at the surgical wound edge and progressing proximally up the posterior medial thigh. At this time, surgical debridement of the eschar and coverage of the amputation stump with split-thickness skin grafting were offered; however, the patient declined. He requested a trial of local wound care with burdock leaf dressing wraps and a honey-based salve, which was a wound care strategy that has worked for others in his community. His wound did not appear infected, specifically there was no marginal erythema, purulence, or local odor, and there were no systemic symptoms of infection. His request was, therefore, honored, and his wound was monitored closely over the subsequent weeks. He utilized a thin layer of B&W ointment applied to burdock leaves (∼2′′ × 4′′) obtained from the local Amish community healthcare supply provider. The leaves were left to soften for 15 min before being individually applied to the eschar and his stump and wrapped in cotton gauze to secure them in place. The dressings were changed twice daily. At his 3-week postoperative follow-up, the eschar was evolving and was more firm with the periphery retracted, revealing a granulation bed without erythema, purulent, or malodorous discharge or any systemic symptom indicative of infection (Fig. 4C). Sutures were removed at 5-week postoperative follow-up. At this point, the eschar showed continued evolution with additional contraction, revealing a larger granulation bed at the periphery of the wound (Fig. 4D).

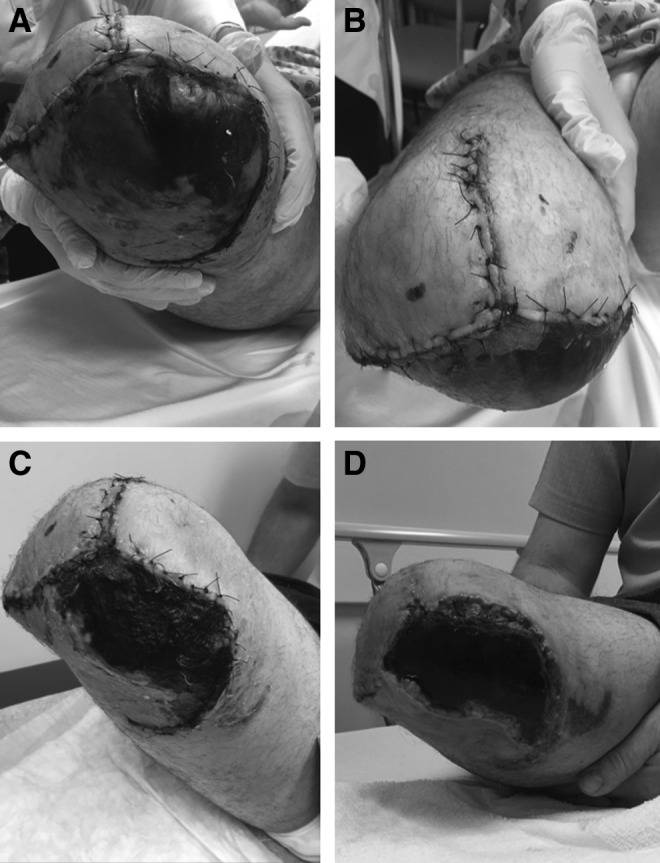

Figure 4.

Postoperative evaluation. Development of large posteromedial eschar at 1 week (A) with preservation of two anterior flaps (B). Maturation of eschar at 3 weeks (C) and 5 weeks (D).

Results

This patient-selected conservative honey and burdock treatment strategy was highly effective for this individual both clinically and regarding his goal to avoid further surgical management if possible. The eschar had nearly completely lysed away by postoperative week 7 and was sharply excised through several intact fibrous adhesions to the underlying granulating bed as a single piece of tissue (Fig. 5A). The honey and burdock treatment was continued by the patient after eschar debridement for a total of 14 weeks. Of note, the patient developed a transient folliculitis during this time period, which was suspected to be due to moisture accumulation and sweat. The patient was advised to minimize the cotton gauze wrapping to allow greater permeability and the rash spontaneously resolved without use of antibiotics within 3–4 days. By week 10, the underlying wound bed was re-epithelialized with primarily healthy tissue except for mild posteromedial erythema and presence of a benign exudative process, with minimal serous fluid, with several superficial erosions indicative of final stages of healing (Fig. 5B). These lesions were treated by superficial debridement in the clinic by the treating surgeon. At no point during follow-up was there concern for infection. By week 14, his stump had matured and was in acceptable form to bear weight through an above-the-knee prosthetic device as evident by viable and healed anterior/distal flaps (Fig. 5C) and posterior soft tissue flaps (Fig. 5D).

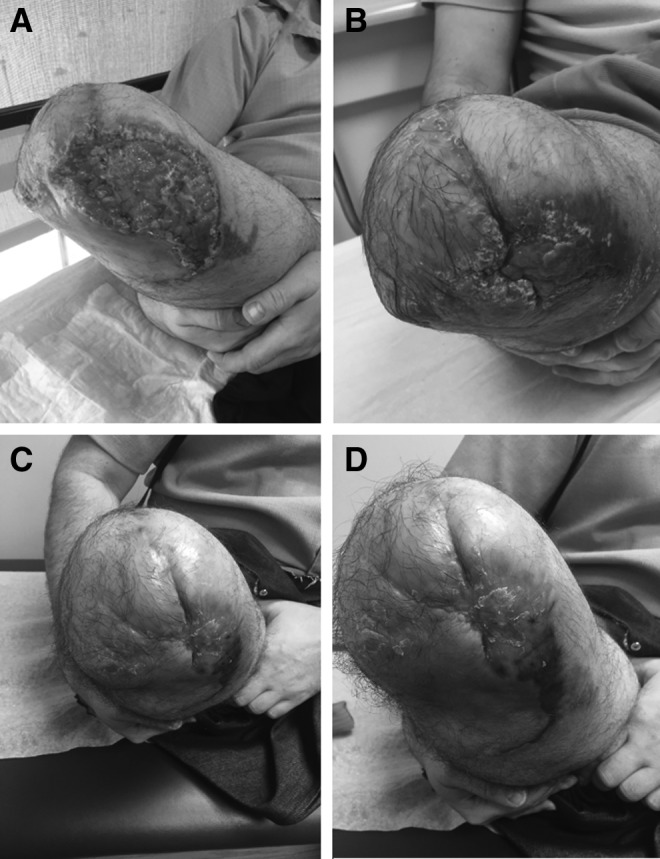

Figure 5.

Post-therapeutic appearance. Progression of wound after eschar removal at 7 weeks (A) 10 weeks (B), and 14 weeks postoperative follow-up demonstrating intact distal medial and lateral coverage (C) and posteromedial coverage (D).

Discussion

The patient presented in this case study did not use tobacco and was generally healthy, with adequate nutritional status, no peripheral vascular disease. The patient was also highly motivated to adhere to the treatment. The patient was able to accommodate regular follow-up to assess wound status for possible complications, which would contraindicate a conservative course.

Moisture retentive dressing strategies are reported to promote wound eschar autolysis by leveraging the body's endogenous proteolytic, fibrinolytic, and collagenolytic mechanisms.25 Larval therapy, a different technique requiring application of sterile maggots to the wound eschar, has been shown to effectively debride and also promote tissue granulation. Larvae are particularly effective in the setting of infection, as they have been shown to eradicate bacterial biofilms during the debridement process.26 In scenarios wherein eschar is present but soft tissue infection is not suspected, application of topical solvents, such as Dakins solution, or exogenous enzymes such as collagenase, can assist in degradation of devitalized tissue. In this case report, we introduce honey and burdock leaves as another less invasive debridement strategy for addressing wound eschar that does not appear infected.

B&W ointment is predominantly honey, a biologic agent that has been widely studied and used in wound therapy.27 There has been increased interest in the role of honey, not least because it may reduce the need for antibiotic therapies. Recent studies have also indicated that honey may have an active regenerative role.28 It is thought that honey acts to modulate the immune response by stimulation and/or inhibition of regulatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6.29 Other active constituents of B&W ointment, such as aloe vera gel,30 comfrey root,31 and wormwood,32 have been investigated individually and shown to be effective in reducing bacterial and fungal activity.

The use of burdock leaves has been less studied in the wound care field. The literature on the medicinal use of burdock leaves focuses on burdock leaf extract rather than whole leaves.33 For example, in dentistry this biologic agent is thought to be effective against oral infections. Pereira et al. studied the antimicrobial activity of burdock leaf extract on several strains of bacteria that are also implicated in soft tissue wound infection, specifically Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida albicans.34 They found that the complex chemical profile of the burdock leaves enables antimicrobial action on several different microbial inhibition zones, indicating burdock leaves appear to have broad antimicrobial efficacy.

Limitations

If tissue is deemed completely nonviable in the initial evaluation of the injury, or infection threatens the soft tissue envelope, then sharp debridement and swift intervention are indicated. Allergies to honey or burdock leaves will contraindicate use of these biologics.

Honey-based salve with burdock leaf dressings was used in combination in this case of patient-centered care in managing the severely mangled extremity. Further study is needed to determine whether honey-based salve or burdock leaf dressings used alone would have similar efficacy in eschar management for this type of injury.

Innovation

Conservative management using a honey-based salve may be a reasonable alternative in the appropriate patient population with close follow-up, in lieu of repeat surgical debridement and placement of skin grafts. Biologic agents have the potential to enhance healing and reduce incident infection. Although the use of honey is commonly reported in diabetic wounds and burn wounds, this case report is, to our knowledge, the first description of honey-based salve and burdock leaves being utilized as a less-invasive alternative to sharp debridement and skin grafting of a traumatic wound eschar to achieve coverage. Necrotic eschar is an impedance to wound healing and can ultimately lead to failure of soft tissue coverage of a lower extremity amputation stump.

Key Findings.

Less invasive approaches to eschar management can increase patient satisfaction and should be considered in similar scenarios.

The use of effective biologic agents can reduce the need for surgical debridement and skin grafts.

Honey-based salve with burdock leaf dressings may provide a less-invasive and highly effective strategy for eschar management.

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

The authors have no acknowledgements. The case study presented is an unfunded study.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- NPWT

negative pressure wound therapy

Author Disclosures and Ghostwriting

No competing financial interests exist. The content of this article was expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Adam Schell, MD, is a third year orthopedic surgery resident at Case Western Reserve University

Jonathan Copp, MD, is a third year orthopedic surgery resident at Case Western Reserve University

Kath M. Bogie, DPhil, is a biomedical engineer whose research interests focus on translational research, particularly in the prevention and treatment of wounds, from biomolecular techniques to clinical assessment and medical device development. Dr. Bogie is an associate professor in the Department of Orthopaedics at Case Western Reserve University and a member of the Board of Directors for the Wound Healing Society.

Robert Wetzel, MD, is an orthopedic trauma surgeon at University Hospitals Case Medical Center and Assistant Professor at Case Western Reserve University in the Department of Orthopaedics.

References

- 1. Herard P, Boillot F. Amputation in emergency situations: indications, techniques and Médecins Sans Frontières France's experience in Haiti. Int Orthop 2012;36:1979–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schirò GR, Sessa S, Piccioli A, Maccauro G. Primary amputation vs limb salvage in mangled extremity: a systematic review of the current scoring system. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shawen SB, Keeling JJ, Branstetter J, Kirk KL, Ficke JR. The mangled foot and leg: salvage versus amputation. Foot Ankle Clin 2010;15:63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nobert N, Moremi N, Seni J, et al. The effect of early versus delayed surgical debridement on the outcome of open long bone fractures at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. J Trauma Manag Outcomes 2016;10:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Melcer T, Walker J, Bhatnagar V, Richard E, Sechriest VF 2nd, Galarneau M. A comparison of four-year health outcomes following combat amputation and limb salvage. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinstein JN, Clay K, Morgan TS. Informed patient choice: patient-centered valuing of surgical risks and benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:726–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gacto-Sanchez P. Surgical treatment and management of the severely burn patient: review and update. Med Intensiva 2017;41:356–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hierner R, Degreef H, Vranckx JJ, Garmyn M, Massagé P, van Brussel M. Skin grafting and wound healing-the “dermato-plastic team approach”. Clin Dermatol 2005;23:343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simman R, Phavixay L. Split-thickness skin grafts remain the gold standard for the closure of large acute and chronic wounds. J Am Col Certif Wound Spec 2011;3:55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Newton K, Dumville JC, Costa ML, Norman G, Bruce J. Negative pressure wound therapy for open traumatic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;7:CD012522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eskes AM, Ubbink DT, Lubbers MJ, Lucas C, Vermeulen H. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: solution for difficult to heal acute wounds? Systematic review. World J Surg 2011;35:535–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dabiri G, Damstetter E, Phillips T. Choosing a wound dressing based on common wound characteristics. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2016;5:32–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levine JM. Dakin's solution: past, present, and future. Adv Skin Wound Care 2013;26:410–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dale BA, Wright DH. Say goodbye to wet-to-dry wound care dressings: changing the culture of wound care management within your agency. Home Healthc Nurse 2011;29:429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abd Jalil MA, Kasmuri AR, Hadi H. Stingless bee honey, the natural wound healer: a review. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2017;30:66–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Minden-Birkenmaier BA, Bowlin GL. Honey-based templates in wound healing and tissue engineering. Bioengineering (Basel) 2018;5:pii [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lu J, Turnbull L, Burke CM, et al. Manuka-type honeys can eradicate biofilms produced by Staphylococcus aureus strains with different biofilm-forming abilities. PeerJ 2014;2:e326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jull AB, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Westby MJ, Deshpande S, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;6:CD005083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holetz FB, Pessini GL, Sanches NR, Cortez DA, Nakamura CV, Filho BP. Screening of some plants used in the Brazilian folk medicine for the treatment of infectious diseases. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2002;97:1027–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keim JW, ed. Burn aid written for the Amish by the Amish. Raleigh, NC: Barefoot Publicaitons, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flurry MD, Herring KL, Carr LW, Hauck RM, Potochny JD. Salve and burdock: a safe, effective amish remedy for treatment of traumatic wounds? Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amish Burn Study Group, Kolacz NM, Jaroch MT, Bear ML, Hess RF. The effect of Burns & Wounds (B&W)/burdock leaf therapy on burn-injured Amish patients: a pilot study measuring pain levels, infection rates, and healing times. J Holist Nurs 2014;32:327–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rieman MT, Neely AN, Boyce ST, et al. Amish burn ointment and burdock leaf dressings: assessments of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. J Burn Care Res 2014;35:e217–e223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taylor BC, Poka A, French BG, Fowler TT, Mehta S. Gritti-stokes amputations in the trauma patient: clinical comparisons and subjective outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:602–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramundo J. Wound debridement. In: Bryant RA, Nix DP, eds. Acute and Chronic Wounds. Current management concepts 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Mosby, 2012:279–288 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Opletalová K, Blaizot X, Mourgeon B, et al. Maggot therapy for wound debridement: a randomized multicenter trial. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al-Waili N, Salom K, Al-Ghamdi AA. Honey for wound healing, ulcers, and burns; data supporting its use in clinical practice. Scientific World Journal 2011;11:766–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinotti S, Bucekova M, Majtan J, Ranzato E. Honey: an effective regenerative medicine product in wound management. Curr Med Chem 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.2174/0929867325666180510141824 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. Majtan J. Honey: an immunomodulator in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2014;22:187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fox LT, Mazumder A, Dwivedi A, Gerber M, du Plessis J, Hamman JH. In vitro wound healing and cytotoxic activity of the gel and whole-leaf materials from selected aloe species. J Ethnopharmacol 2017;200:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sowa I, Paduch R, Strzemski M, et al. Proliferative and antioxidant activity of Symphytum officinale root extract. Nat Prod Res 2018;32:605–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trinh H, Yoo Y, Won KH, et al. Evaluation of in-vitro antimicrobial activity of Artemisia apiacea H. and Scutellaria baicalensis G. extracts. J Med Microbiol 2018;67:489–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferracane R, Graziani G, Gallo M, Fogliano V, Ritieni A. Metabolic profile of the bioactive compounds of burdock (Arctium lappa) seeds, roots and leaves. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2010;51:399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pereira JV, Bergamo DC, Pereira JO, França Sde C, Pietro RC, Silva-Sousa YT. Antimicrobial activity of Arctium lappa constituents against microorganisms commonly found in endodontic infections. Braz Dent J 2005;16:192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]