Significance

Malaria, the disease caused by Plasmodium spp. infection, remains a major global cause of morbidity and mortality, claiming the lives of over ∼4.5 × 105 individuals per year. Paradoxically, however, up to 98% of infected individuals survive the infection, establishing disease tolerance to malaria. We found that this host defense strategy, which does not target Plasmodium directly, relies on the capacity of renal proximal tubule epithelial cells to detoxify labile heme, a pathologic by-product of hemolysis that accumulates in plasma and urine during the blood stage of infection. This defense strategy prevents the onset of acute kidney injury, a clinical hallmark of severe malaria.

Keywords: infection, malaria, disease tolerance, heme, kidney

Abstract

Malaria, the disease caused by Plasmodium spp. infection, remains a major global cause of morbidity and mortality. Host protection from malaria relies on immune-driven resistance mechanisms that kill Plasmodium. However, these mechanisms are not sufficient per se to avoid the development of severe forms of disease. This is accomplished instead via the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria, a defense strategy that does not target Plasmodium directly. Here we demonstrate that the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria relies on a tissue damage-control mechanism that operates specifically in renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTEC). This protective response relies on the induction of heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1; HO-1) and ferritin H chain (FTH) via a mechanism that involves the transcription-factor nuclear-factor E2-related factor-2 (NRF2). As it accumulates in plasma and urine during the blood stage of Plasmodium infection, labile heme is detoxified in RPTEC by HO-1 and FTH, preventing the development of acute kidney injury, a clinical hallmark of severe malaria.

Disease tolerance is an evolutionarily conserved defense strategy against infection, first described as a central component of plant immunity (1). Over the past decade it became apparent that this defense strategy is also operational in animals, including mammals where it confers protection against malaria (2, 3).

The blood stage of Plasmodium spp. infection is characterized by the invasion of host red blood cells (RBC), in which this protozoan parasite proliferates extensively, consuming up to 60–80% of the RBC hemoglobin (HB) content (4). Plasmodium spp. do not express a HMOX1 ortholog gene (5) and cannot catalyze the extraction of Fe from heme, acquiring Fe via heme auto-oxidation while also polymerizing labile heme into redox-inert hemozoin and avoiding its cytolytic effects (6).

Once the physical integrity of infected RBC becomes compromised, the remaining RBC HB content is released into plasma, where extracellular α2β2 HB tetramers disassemble into αβ dimers that undergo auto-oxidation, eventually releasing their noncovalently bound heme (7). As it accumulates in plasma, labile heme is loosely bound to plasma acceptor proteins, macromolecules, or low-molecular-weight ligands that fail, however, to control its redox activity (8). A fraction of the labile heme in plasma becomes bioavailable, acting in a pathogenic manner and compromising the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria (2, 7, 9).

Heme accumulation in plasma and urine of malaria patients is associated with the development of acute kidney injury (AKI), a clinical hallmark of severe malaria (10–12). Similarly, heme accumulation in plasma, as a consequence of rhabdomyolysis, is also associated with the development of AKI (13). While heme partakes in the pathogenesis of AKI associated with rhabdomyolysis, whether this is the case for severe malaria has not been established.

We have previously shown that heme detoxification by the stress-responsive enzyme HO-1 is a limiting factor in the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria (2, 7). In a similar manner, heme detoxification by HO-1 also prevents the development of AKI following rhabdomyolysis (13). This protective effect requires that the Fe extracted from heme is neutralized by the ferroxidase active FTH component of the ferritin complex (14), establishing disease tolerance to malaria (9) and preventing development of AKI following rhabdomyolysis (14). Here we asked whether heme catabolism by HO-1 and Fe sequestration by FTH act locally in the kidney to prevent the development of AKI and establish disease tolerance to malaria.

Results

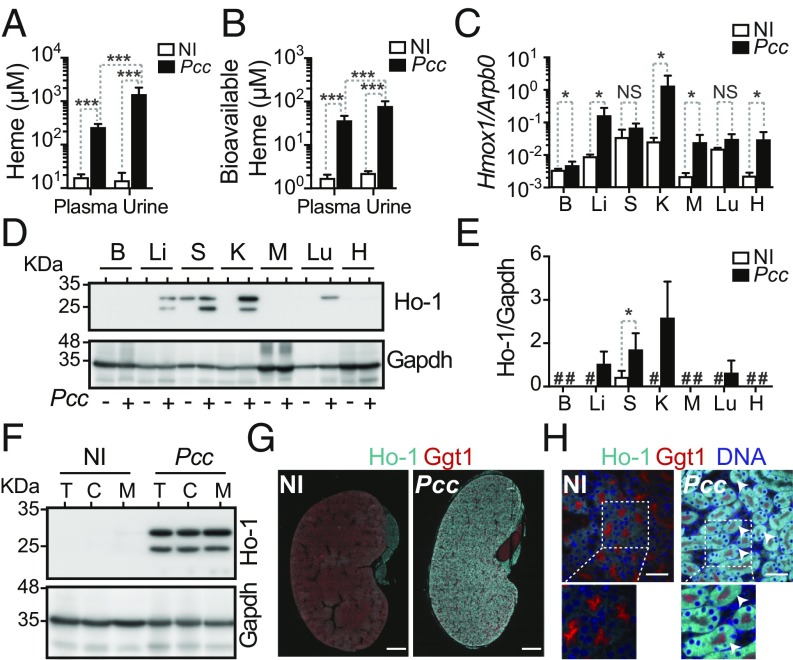

Malaria is associated with HO-1 induction in renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTEC). Consistent with heme accumulation in plasma and urine of individuals developing severe forms of malaria (9, 15), Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi (Pcc)-infected C57BL/6 mice accumulated heme in plasma and urine (Fig. 1A). Approximately 15% of the heme in plasma and 6% in urine were bioavailable (Fig. 1B), as assessed using a cellular-based heme-reporter assay (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). Heme and labile heme concentration in urine was higher than in plasma, suggesting that labile heme is actively excreted into urine.

Fig. 1.

HO-1 expression is induced in RPTEC during Plasmodium infection. (A) Heme and (B) bioavailable heme concentration (mean ± SD) in plasma and urine of C57BL/6 mice, not infected (NI; n = 7) or 7 d after Pcc infection (n = 8). Data are from one experiment. (C) Hmox1 normalized to Arbp0 mRNA (mean ± SD) in brain (B), liver (Li), spleen (S), kidney (K), muscle (M), lung (Lu), and heart (H) of C57BL/6 mice, not infected (NI; n = 3) or 7 d after Pcc infection (n = 6). Data are from one experiment. (D) HO-1 and Gapdh protein expression detected by Western blot in the brain (B), liver (Li), spleen (S), kidney (K), muscle (M), lung (Lu), and heart (H) of C57BL/6 mice, not infected (NI) or 7 d after Pcc infection. Data are representative of four mice per group in one experiment. (E) Densitometry analysis (mean ± SD) of proteins in the same experiment as D. #: protein levels below detection limit for the exposure time analyzed. (F) HO-1 and Gapdh protein detected by Western blot in total kidney (T), renal cortex (C), and renal medulla (M) of C57BL/6 mice, not infected (NI) or 7 d after Pcc infection. Data are representative of four mice per group in one experiment. (G) Kidney immunostaining in C57BL/6 mice, not infected (NI) or 7 d after Pcc infection. Gamma glutamyl transferase 1 (Ggt1; red) was used as a RPTEC marker. Image is representative of three mice per group in one experiment. (Scale bar: 1,000 µm.) (H) Kidney immunostaining, as in G. DAPI (blue) was used to counterstain DNA. Arrowheads highlight HO-1 (cyan) in Ggt1+ RPTEC. Images are representative of five random fields from four to six mice per group in one experiment. (Scale bar: 50 µm.) P values in A and B, comparing log-transformed heme concentration values, were determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests, and in C and E using Mann–Whitney U test. NS: not significant (P > 0.05); *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Consistent with our previous findings (9, 16), Hmox1 mRNA (Fig. 1C) and Ho-1 protein (Fig. 1 D and E) were induced in the liver of Pcc-infected mice. Hmox1 mRNA and Ho-1 protein were also induced in other organs, including in the kidneys (Fig. 1 C–E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). Expression of Ho-1 in the kidney was induced in the cortex and in the medulla (Fig. 1 F and G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A), predominantly in RPTEC (Fig. 1H and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). This suggests that, as it accumulates in plasma and urine during the blood stage of Plasmodium infection, labile heme is up taken by RPTEC, where it is catabolized by HO-1.

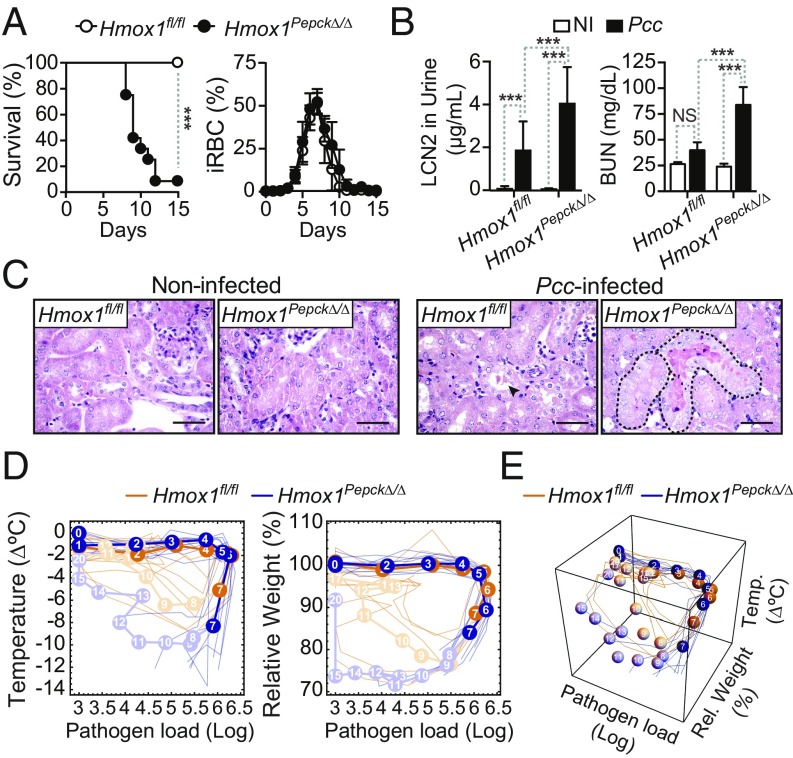

HO-1 expression in RPTEC is essential to establish disease tolerance to malaria. To determine whether heme catabolism in RPTEC is involved in the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria, we generated Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice, in which Hmox1 is deleted specifically in RPTEC (17) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Pcc-infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice succumbed to Pcc infection, compared with control Hmox1fl/fl mice that survived and resolved the infection (Fig. 2A). Mortality of Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice was not associated with changes in parasitemia, compared with control Hmox1fl/fl mice (Fig. 2A). This suggests that heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC is essential to establish disease tolerance to malaria.

Fig. 2.

HO-1 expression in RPTEC establishes disease tolerance to malaria. (A) Survival and percentage of iRBC (mean ± SD) in Pcc-infected Hmox1fl/fl (n = 7) and Hmox1PepcKΔ/Δ (n = 12) mice. Data from four independent experiments with similar trend. (B) Lcn2 concentration in urine and BUN (mean ± SD) in noninfected (NI) and Pcc-infected Hmox1PepcKΔ/Δ (NI: 5–11; Pcc: n = 7–12) and Hmox1fl/fl (NI: n = 6–11; Pcc: n = 9–13) mice, 7 d after infection. Data from two experiments with a similar trend. (C) Kidney H&E staining in noninfected and 7 d after Pcc infection. Representative of four to five mice per genotype in two experiments. (Scale bar: 50 µm.) Arrowhead indicates HB casts, and dashed lines outline tubular necrosis. (D) Individual disease trajectories of the same mice as in A. Circles represent median of disease trajectories, and corresponding numbers are days after infection (day 0). Portion of the disease trajectories in darker color indicates days before onset of mortality in Hmox1PepcKΔ/Δ mice. (E) The 3D plot of disease trajectories from the same mice as in D. Statistical differences between genotypes became significant (P = 0.008; Mann–Whitney U test) on day 7 before onset of mortality in Hmox1PepcKΔ/Δ mice. P values in A were determined using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test and in B using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. NS, not significant (P > 0.05); ***P < 0.001.

Lethality of Pcc-infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice was associated with the development of AKI, as illustrated by the accumulation of Lipocalin 2 (LCN2) in urine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (Fig. 2B). AKI in Pcc-infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice was characterized histologically by widespread acute tubular necrosis and HB casts affecting up to 15% of the renal cortex, compared with sparse tubular single-cell death and HB casts in control Pcc-infected Hmox1fl/fl mice (Fig. 2C). This suggests that during the blood stage of Plasmodium infection, the induction of heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC is essential to prevent the development of AKI, a clinical hallmark of severe malaria (10–12).

The extent of liver damage, another clinical hallmark of severe malaria captured in Pcc-infected mice (9, 16), was similar in infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ vs. Hmox1fl/fl mice, as assessed serologically (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). This suggests that heme catabolism in RPTEC does not counter the development of liver damage.

The complete blood count profile of Pcc-infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ and Hmox1fl/fl mice was indistinguishable (SI Appendix, Table S1), suggesting that HO-1 expression in RPTEC does not impact on the development of hemolytic anemia during Plasmodium infection. Blood neutrophilia was also similar in Pcc-infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ vs. Hmox1fl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Table S1), suggesting that HO-1 expression in RPTEC does not impact on neutrophil activation.

Disease tolerance can be inferred from the analysis of “disease trajectories” established by the temporal relationship of specific host homeostatic variables versus pathogen load (18). The disease trajectories of Pcc-infected Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice were distinct from those of Pcc-infected control Hmox1fl/fl mice, when analyzing body temperature vs. body weight vs. pathogen load (Fig. 2 D and E). Differences among genotypes were statistically significant as early as 7 d after infection, before the onset of lethality in Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ mice (Fig. 2 D and E). This suggests that heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC is required to maintain vital homeostatic parameters, such as body temperature and body weight, within a dynamic range compatible with survival from Plasmodium infection.

HO-1 expression in cell compartments other than RPTEC is not essential to establish disease tolerance to malaria. Ubiquitous deletion of Hmox1 in Hmox1R26∆/∆ mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) recapitulated the deletion of Hmox1 specifically in RPTEC, impairing survival to Pcc infection under pathogen loads similar to control Hmox1fl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). The disease trajectories established by Pcc-infected were also distinct from those of Pcc-infected control Hmox1fl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). We then asked whether Hmox1 deletion in cell compartments—where heme catabolism by HO-1 would be expected to act in a protective manner—impaired disease tolerance to Pcc infection. However, Hmox1 deletion specifically in myeloid cells of Hmox1LysMΔ/Δ mice (19), macrophages and dendritic cells of Hmox1Cd11cΔ/Δ mice, vascular endothelial and hematopoietic cells of Hmox1Tie2Δ/Δ mice, hepatocytes and hematopoietic cells of Hmox1Mx1Δ/Δ mice, or neuronal cells of Hmox1NestinΔ/Δ mice failed to compromise disease tolerance to Pcc infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–I). This reinforces the notion that heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC is a limiting factor in the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria.

We then questioned whether HO-1 expression in RPTEC is also essential to establish disease tolerance to other infectious hemolytic conditions and tested this using an experimental model of hemolytic Escherichia coli (clinical isolate strain CFT073) infection (20). The lethality of E. coli CFT073 infection was similar in Hmox1Pepck∆/∆ vs. control Hmox1fl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), indicating that heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC is not essential to establish disease tolerance to hemolytic bacterial infections.

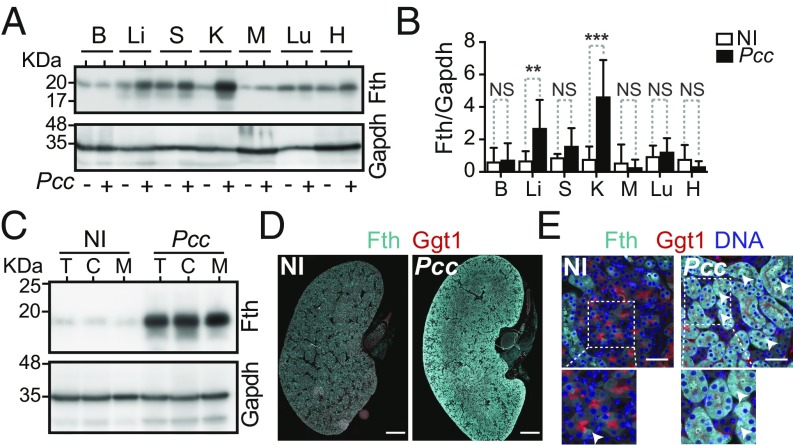

Malaria is associated with the induction of FTH in RPTEC. The Fe released via heme catabolism by HO-1 induces posttranscriptionally the expression of FTH (21). Consistent with this notion and in keeping with our previous findings (9), Fth expression was induced in the liver of Pcc-infected C57BL/6 mice, as assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 3 A and B). This was also the case in the kidney (Fig. 3 A and B), where we had previously failed to detect Fth induction in response to Pcc infection (9), most likely owing to technical reasons. Induction of Fth expression in the kidney occurred both in the cortex and the medulla (Fig. 3 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), predominantly in RPTEC (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B).

Fig. 3.

FTH expression is induced in RPTEC during Plasmodium infection. (A) Fth and Gapdh protein expression in brain (B), liver (Li), spleen (S), kidney (K), muscle (M), lung (Lu), and heart (H) of C57BL/6 mice, noninfected (NI) or 7 d after Pcc infection. Western blot representative of nine mice, from two independent experiments with the same trend. (B) Densitometry analysis (mean ± SD) of proteins shown in A. n = 9 mice per group from two experiments. (C) Fth and Gapdh protein levels in total kidney (T), renal cortex (C), and renal medulla (M) of C57BL/6 mice, not infected (NI) or 7 d after Pcc infection. Data are representative of four mice per group from one experiment. (D) Kidney immunostaining in C57BL/6 mice, noninfected (NI) or 7 d after Pcc infection. Gamma glutamyl transferase 1 (Ggt1; red) was used as a RPTEC marker. Image is representative of three mice per group in one experiment. (Scale bar: 1,000 µm.) (E) Kidney immunostaining, as in D. DAPI (blue) was used to counterstain DNA. Arrowheads highlight Fth (cyan) in Ggt1+ RPTEC. Images are representative of five random fields from four to six mice per group in one experiment. (Scale bar: 50 µm.) P values in B determined using Mann–Whitney U test. NS, not significant (P > 0.05); **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

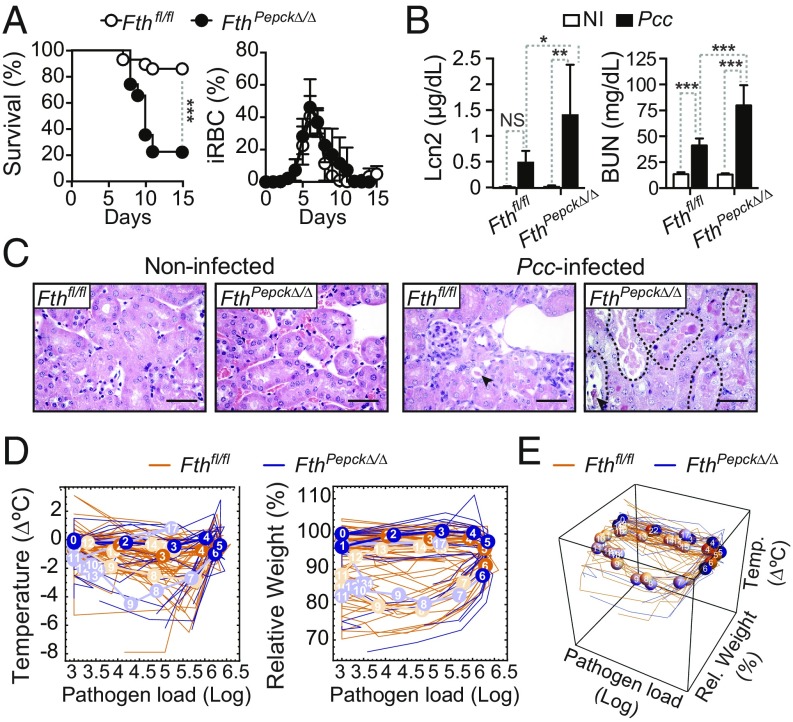

FTH expression in RPTEC is essential to establish disease tolerance to malaria. To assess whether FTH expression in RPTEC contributes to the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria, we generated FthPepck∆/∆ mice, in which Fth is deleted specifically in RPTEC (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A) (14). More than 75% of FthPepck∆/∆ mice succumbed to Pcc infection, as compared to 13.3% of control Pcc-infected Fthfl/fl mice (Fig. 4A). This was not associated with changes in pathogen load (Fig. 4A), suggesting that Fe storage by Fth in RPTEC is essential to establish disease tolerance to Pcc infection. Of note, Hmox1 expression was highly induced in the kidneys of Pcc-infected FthPepck∆/∆ vs. Fthfl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), demonstrating that heme catabolism by Ho-1 per se fails to establish disease tolerance to malaria, if not coupled to Fe storage by Fth. Moreover, when considering Hmox1 induction as a biomarker of cell stress, it becomes apparent that, in the absence of Fth, heme catabolism by HO-1 is deleterious in RPTEC.

Fig. 4.

FTH expression in RPTEC is essential to establish disease tolerance to malaria. (A) Survival and percentage of iRBC (mean ± SD) of Pcc-infected FthPepcKΔ/Δ (n = 23) and Fthfl/fl (n = 30) mice. Data are from six independent experiments with a similar trend. (B) Lcn2 plasma concentration and BUN (mean ± SD) in noninfected and Pcc-infected FthPepcKΔ/Δ (NI: n = 5–10; Pcc: n = 7) and Fthfl/fl (NI: n = 5; Pcc: n = 7) mice, 7 d after infection. Data are from three experiments. (C) H&E staining of kidney sections from noninfected (NI) and Pcc-infected FthPepcKΔ/Δ and Fthfl/fl mice, 9 d after infection. Arrowheads indicate HB casts, and dashed lines outline tubular necrosis. Images are representative of two to seven mice per genotype in four experiments. (Scale bar: 50 µm.) (D) Individual disease trajectories of Pcc-infected FthPepcKΔ/Δ (n = 17) and Fthfl/fl (n = 10) mice from three independent experiments with a similar trend. Circles represent median of disease trajectories, and corresponding numbers indicate days after infection (day 0). Portion of disease trajectories in darker color indicates days before onset of mortality in FthPepcKΔ/Δ mice. (E) The 3D plot of disease trajectories from the same mice as in D. Statistical differences between genotypes became significant on day 6 after Pcc infection (P = 0.00007; Mann–Whitney U test) before onset of mortality of FthPepcKΔ/Δ mice. P values in A were determined using a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test and in B using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. NS, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Pcc-infected FthPepck∆/∆ mice developed AKI, as illustrated by Lcn2, BUN, and cystatin C accumulation in plasma (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S7C), compared with control Fthfl/fl mice. AKI in Pcc-infected FthPepck∆/∆ mice was associated with acute tubular necrosis and intraluminal HB casts, affecting up to 40% of the renal cortex, compared with control Pcc-infected Fthfl/fl mice that developed only discrete and rare tubular epithelial cell necrosis or HB casts in the renal cortex (Fig. 4C). Expression of Lcn2 mRNA was also higher in the kidneys of Pcc-infected FthPepck∆/∆ vs. Fthfl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S7D).

The disease trajectories established by the temporal relationship of body temperature vs. body weight vs. pathogen load showed significant differences in Pcc-infected FthPepck∆/∆ vs. Fthfl/fl mice (Fig. 4 D and E), including before the onset of lethality. This suggests that FTH expression in RPTEC is essential to maintaining vital homeostatic factors such as body temperature and body weight within a range compatible with host survival.

We have previously shown that composite Fth deletion in FthMx1∆/∆ mice compromises disease tolerance to Pcc infection (9). This suggests that Fe storage by FTH, in cellular compartments other than RPTEC, may contribute to disease tolerance to malaria. However, Fth deletion in myeloid cells of FthLysMΔ/Δ mice, hepatocytes of FthAlbΔ/Δ mice, or vascular endothelial cells of FthCdh5Δ/Δ mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A–E) failed to compromise disease tolerance to Pcc infection. This suggests that deletion of Fth in the kidney (22) contributes critically to our previous observation that FthMx1∆/∆ mice fail to establish disease tolerance to malaria (9).

FTH expression in RPTEC does not regulate local immune responses. We asked whether FTH expression in RPTEC modulates kidney immunopathology, as assessed by renal leukocyte infiltration. Neutrophils, inflammatory monocytes, and CD4+ as well as CD8+ T cells accumulated to a similar extent in the kidneys of Pcc-infected FthPepck∆/∆ vs. Fthfl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A–F). The same was true for T cell proliferation, as monitored by Ki67 expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 G–J). This suggests that FTH expression in RPTEC does not impact on the extent of kidney leukocyte infiltration.

FTH expression by RPTEC is not essential to establish disease tolerance to hemolytic bacterial infections. Mortality from E. coli CFT073 infection in FthPepck∆/∆ was similar to that in Fthfl/fl mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). This suggests that, similarly to HO-1, FtH expression in RPTEC is not required per se to provide a survival advantage against infection by this hemolytic bacterium.

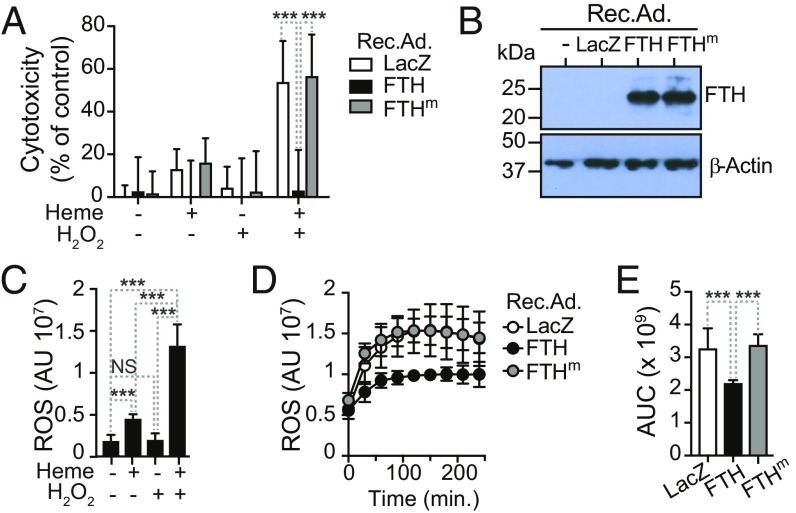

FTH is cytoprotective in RPTEC. We reasoned that FTH might protect RPTEC from the cytotoxic effects of labile heme, as it accumulates in plasma and urine during the blood stage of Plasmodium infection (Fig. 1A). In keeping with previous findings in other parenchyma cells (16, 23, 24), heme enhanced the cytotoxic effect of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on human RPTEC in vitro, compared with exposure to heme or H2O2 alone (Fig. 5A). Transduction of human RPTEC in vitro with a recombinant adenovirus (Rec.Ad.) encoding FTH (Fig. 5B) was cytoprotective against heme plus H2O2, compared with control cells transduced with a Rec.Ad. encoding β-galactosidase (LacZ) (Fig. 5A). Human RPTEC were not protected against heme plus H2O2 when transduced with a Rec.Ad. encoding a FTH mutant (FTHm) lacking ferroxidase activity (Fig. 5 A and B) (9, 25), suggesting that the ferroxidase activity of FTH is required to counter the cytotoxic effects of labile heme and H2O2 in human RPTEC.

Fig. 5.

FTH protects RPTEC from heme cytotoxicity. (A) Human RPTEC were transduced in vitro with Rec.Ad. (10 pfu/cell) encoding β-galactosidase (LacZ), human FTH, or mutated human FTH (FTHm) lacking ferroxidase activity and exposed to heme (5 µM) and/or H2O2 (50 µM). Cytotoxicity was measured using a 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide-based cell viability assay, as detailed in SI Appendix. Data (mean ± SD) are from two independent experiments with a similar trend. (B) Relative expression of FTH and β-actin in human RPTEC transduced with LacZ, FTH, or FTHm Rec.Ad, detected by Western blot in one experiment representative of two with a similar trend. (C) ROS accumulation (mean ± SD) in human RPTEC exposed to heme (5 µM) and/or H2O2 (50 µM), detected using the CM-H2DCFDA probe. Data are from two independent experiments with a similar trend. (D) Time course of ROS accumulation (mean ± SD) in human RPTEC transduced and treated as in A. Data are from two independent experiments with a similar trend. (E) Quantification of data from D. AUC: area under the curve. P values in A determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test; in C and E using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. NS, not significant; ***P < 0.001.

We then tested whether the cytoprotective effect of FTH is mediated via a mechanism that prevents Fe from catalyzing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Human RPTEC accumulated high levels of ROS when exposed in vitro to heme plus H2O2, compared with heme or H2O2 alone (Fig. 5C). This is in keeping with previous observations that heme promotes ROS generation in parenchyma cells exposed to a variety of inflammatory agonists (23, 24). Transduction of human RPTEC with an FTH, but not an FTHm Rec.Ad., suppressed ROS accumulation, compared with control cells transduced with a LacZ Rec.Ad. (Fig. 5 D and E). This further supports the interpretation that the ferroxidase activity of FTH is critical to limit the pro-oxidant and cytotoxic effects of intracellular labile Fe, generated via heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC. Presumably, this explains why, in the absence of FTH, HO-1 fails to confer disease tolerance to malaria.

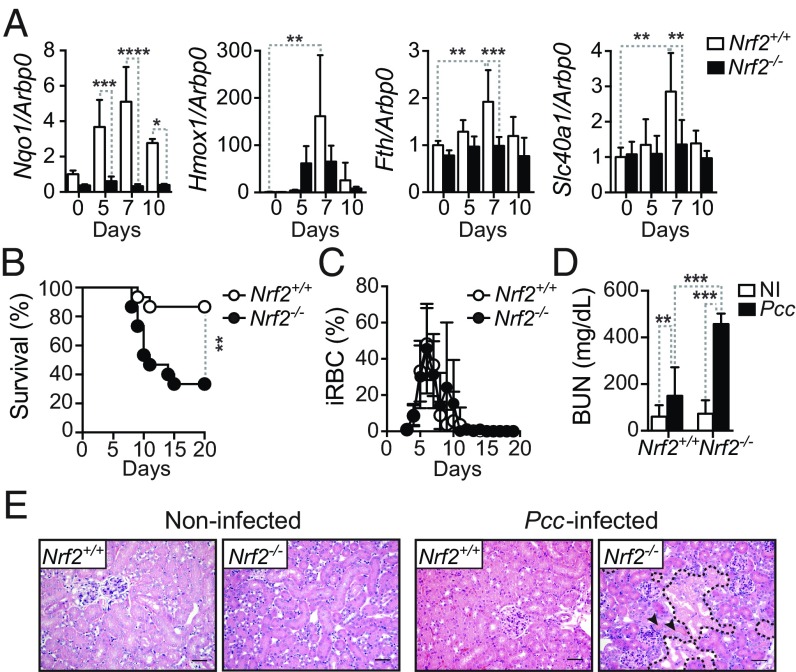

The transcription factor NRF2 controls the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria. Upon activation NRF2 can induce Hmox1 (26) and Fth (27), and therefore we asked whether NRF2 is required to support the induction of these genes in the kidneys of Pcc-infected mice, preventing the development of AKI and establishing disease tolerance. Expression of NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (Nqo1), a prototypical NRF2-responsive gene (28), was induced in the kidneys of Pcc-infected wild type (Nrf2+/+) but not in Pcc-infected Nrf2-deficient (Nrf2−/−) mice (Fig. 6A). This suggests that NRF2 is activated in the kidneys in response to Pcc infection. Similar, although less pronounced, the expression of Hmox1, Fth, and Ferroportin-1 (Fpn1; solute carrier family 40 member 1; Slc40a1) was also induced in the kidney during Pcc infection in Nrf2+/+ but to a lesser extent in Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 6A). This suggests that NRF2 activation in response to Plasmodium infection supports the induction of HO-1, FTH, and FPN1 in the kidney.

Fig. 6.

The transcription factor NRF2 protects from AKI and is essential to establish disease tolerance to Pcc infection. (A) Expression of Nqo1, Hmox1, Fth, and Slc40a1 normalized to Arbp0 mRNA in the kidneys of noninfected (NI) or Pcc-infected Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice (n = 3–5 per group). Data are represented as mean expression relative to NI Nrf2+/+ mice ± SD from three independent experiments with a similar trend. (B) Survival of Pcc-infected Nrf2+/+ (n = 15) and Nrf2−/− mice (n = 15). Data are from three independent experiments with a similar trend. (C) Percentage of iRBC (mean ± SD) in Pcc-infected Nrf2+/+ (n = 10) and Nrf2−/− mice (n = 10). Data are from two independent experiments with a similar trend. (D) BUN (mean ± SD) in noninfected (NI) and 10 d after Pcc infection in Nrf2−/− (NI: n = 20; Pcc: n = 13) and control Nrf2+/+ (NI: n = 20; Pcc: n = 14) mice. Data from four independent experiments with similar trend. (E) Representative kidney H&E staining in noninfected and Pcc-infected Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice 10 d after infection. Arrowheads indicate HB casts, and dashed lines outline tubular necrosis. Images representative of two independent experiments (n = 8–10 per genotype). (Scale bar: 50 μm.) P values in A and D determined using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test and in B using log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. NS, not significant (P > 0.05); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

About 80% of Nrf2−/− mice succumbed to Pcc infection, compared with 20% of control Pcc-infected Nrf2+/+ mice (Fig. 6B), with similar pathogen loads (Fig. 6C). Pcc-infected Nrf2−/− mice developed AKI, as illustrated by a higher BUN (Fig. 6D), and extensive acute tubular necrosis (Fig. 6E), compared with Nrf2+/+ mice. This suggests that NRF2 acts upstream of HO-1, FTH, and FPN1 to promote the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria.

Given the involvement of other transcription factors, such as the heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) (29) and hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1α) (30), in the regulation of HMOX-1 expression, we addressed whether these transcription factors were also involved in the establishment of disease tolerance to Pcc infection. To test this hypothesis, we generated Hsf1R26∆/∆ and Hif1αR26∆/∆ mice, in which Hsf1 or Hif1α, respectively, are globally deleted in an inducible manner (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A and B). Lethality and parasitemias of Pcc-infected Hsf1R26∆/∆ and Hif1αR26∆/∆ mice were similar to control Hsf1fl/fl and Hif1αfl/fl mice, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 C–F). This suggests that neither HSF1 nor HIF1α are involved in the establishment of disease tolerance to Pcc infection.

Discussion

Most of the Fe contained in the prosthetic heme groups of HB must be continuously recycled, redirected toward heme biosynthesis, and incorporated into nascent HB during erythropoiesis (31). Hemophagocytic macrophages are at a center stage in this Fe-recycling process, engulfing an estimated 2 × 106 senescent RBC and processing 2 × 1015 heme molecules per second in healthy humans (31, 32). The pathologic outcomes associated with disruption of this Fe-recycling process during hemolytic conditions are countered by the recruitment of circulating monocytes that differentiate into tissue resident Fe-recycling hemophagocytic macrophages (33). When the recruitment and differentiation of these macrophages is impaired, hemolytic conditions become associated with the development of AKI (33). Given that AKI is a hallmark of severe malaria (10–12), it is reasonable to speculate that impairment of hemophagocytic macrophage function (34) contributes to the pathogenesis of malaria-associated AKI, but this remains to be formally established.

Presumably, defective hemophagocytic macrophage function associated with malaria (34) also favors the accumulation of damaged RBC in the circulation, leading to intravascular hemolysis and heme accumulation in plasma as well as in urine (Fig. 1 A and B). Of note, labile heme accumulates at higher concentrations in urine than in plasma (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the kidney actively excretes heme during the blood stage of Plasmodium infection.

Labile heme is cytotoxic to RPTEC (Fig. 5 A, C, and D), likely precipitating the development of AKI (13, 14). This pathologic process is countered by the induction of HO-1 in RPTEC, avoiding the development of AKI and establishing disease tolerance to malaria (Fig. 2 A–C). The observation that induction of HO-1 in cell compartments other than RPTEC is not essential per se to establish disease tolerance to malaria (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) suggests that heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC acts as a limiting factor in the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria. This does not exclude, however, HO-1 induction in other organs, such as the liver (Fig. 1 C–E) (9), from contributing to this defense strategy. However, in the absence of HO-1 expression by RPTEC, this is not sufficient to establish disease tolerance to malaria (Fig. 2).

Our findings suggest that the Fe extracted from heme catabolism by HO-1 in RPTEC leads to the induction of ferritin (Fig. 3). In our previous work, however, we did not observe an induction of Fth in the kidneys of Pcc-infected mice, likely owing to technical reasons (9). Using different approaches, we have now established unequivocally that the blood stage of Plasmodium infection is associated with the induction of FTH in the kidneys as well as in other organs such as the liver and skeletal and cardiac muscle (Fig. 3 A and B). Moreover, we found that the induction of FTH expression in the kidneys and, more specifically, in RPTEC (Fig. 3 C–E) is essential to prevent the development of AKI and establish disease tolerance to malaria (Fig. 4). This is most likely because of the cytoprotective effect of FTH (9, 23) that prevents RPTEC from undergoing programmed cell death (Fig. 5) and suppresses the development of AKI (Fig. 4).

Our current findings are in keeping with our previous observation that composite deletion of Fth in FthMx1Δ/Δ mice (22) compromises the establishment of disease tolerance to Plasmodium infection (9), considering that Cre-mediated Fth deletion in Mx1Cre mice occurs in several organs including in the kidneys (22). This suggests, however, that expression of Fth in hepatocytes is not essential to establish disease tolerance to malaria, as demonstrated using FthAlbΔ/Δ mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). This does not exclude, however, Fth expression in hepatocytes or other parenchyma cells from contributing to the establishment of disease tolerance to malaria.

Our current finding that HO-1 and FTH expression in RPTEC confers protection against malaria is also consistent with previous demonstrations of HO-1 and FTH induction in RPTEC being protective against noninfectious hemolytic conditions, such as warm antibody hemolytic anemia (35) and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (36). Moreover, others and we have shown that HO-1 and FTH induction in RPTEC is also protective against different experimental models of heme-driven kidney injury (13, 14). Finally, it is worth noting that global deletion of Hmox1 in mice (37) and humans (38) is associated with the development of kidney injury.

We have previously shown that sickle HB establishes disease tolerance to malaria via a mechanism involving the induction of HO-1 by the transcription factor NRF2 (2). The transcriptional program orchestrated by NRF2 also induces the expression of FTH (Fig. 6A), which is essential to confer disease tolerance to the blood stage of Pcc infection (Fig. 6 B and C) (9), preventing the pathogenesis of AKI (Fig. 6 D and E). This suggests therefore that the transcriptional program controlled by NRF2 in RPTEC is essential to prevent acute tubular necrosis underlying the development of AKI.

As suggested by previous studies (18), the establishment of disease tolerance to Pcc infection can be inferred from the analyses of disease trajectories (Fig. 2 D and E and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and Fig. 4 D and E). Accordingly, Hmox1 or Fth deletion in RPTEC gave rise to disease trajectories with a sharp decline of body temperature, occurring irrespective of pathogen load (Figs. 2 D and E and 4 D and E). One possible explanation for why the expression of these genes in the kidney controls body temperature likely relates to a cross-talk between Fe and glucose metabolism in which intracellular Fe accumulation inhibits endogenous glucose production via gluconeogenesis (25). Of note, kidney gluconeogenesis is essential to control of glycemia in response to different forms of stress (39), and glucose is a major source of energy controlling thermoregulation and the establishment of disease tolerance to Plasmodium infection (40). We speculate that expression of HO-1 and FTH in RPTEC might regulate kidney glucose production in a manner that impacts on thermoregulation and the establishment of disease tolerance to Plasmodium infection, which, however, remains to be established.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the existence of a previously unsuspected tissue damage-control mechanism that operates specifically in the kidneys to establish disease tolerance to Plasmodium infection. We propose that targeting components of this defense mechanism may be of therapeutic value in the treatment of severe malaria without the selection of drug resistance in Plasmodium spp.

Materials and Methods

Plasmodium Infections.

Mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC). Experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the IGC (A008.2010 and A009.2011) and the Portuguese National Entity (Direcção Geral de Alimentação e Veterinária; 008959 and 018071). Experimental procedures were performed according to the Portuguese (Decreto-Lei 113/2013) and European (Directive 2010/63/EU) legislations. Mice were infected by i.p. inoculation of blood isolated from mice infected with a Pcc AS strain [2 × 106 infected red blood cells (iRBC)]. Mice were monitored daily for parasitemia, weight, temperature, RBC number, and survival.

Serology.

Mice were killed and plasma was obtained at the indicated time points after Plasmodium infection. BUN and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were quantified using quantitative colorimetric determination kits (QuantiChrom and EnzyChrom; Bioassay Systems) and Lcn2 and Cystatin C by ELISA, as detailed in SI Appendix.

Adenoviral Transduction in Human RPTEC.

Human RPTEC (ScienCell Research Laboratories) were transduced (50% confluence) with recombinant adenovirus encoding FTH, ferroxidase-deleted FTH, and LacZ, as described (9, 25). Briefly, RPTEC were exposed to Rec.Ad. (10 pfu/cell, 6 h) and, within 48–72 h, exposed to hemin (5 μM) and/or H2O2 (50 μM) and monitored for survival and ROS production, as detailed in SI Appendix.

For detailed materials and methods, see SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia Grants PTDC/SAU-TOX/116627/2010, HMSP-ICT/0018/2011, and LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-029411 (to M.P.S.); SFRH/BPD/101608/2014 (to A.R.C.); and SFRH/BD/51877/2012 (to A.R.). S. Rebelo and T.W.A. are supported by Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian Grant 217/BD/17; B.S., S.C., L.d.B., R.G., and S. Ramos by European Union 7th Framework Grant ERC-2011-AdG 294709 (to M.P.S.); V.J. by Hungarian National Research, Development, and Innovation Office Grant K116024; F.B. by Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellowship 707998; R.M. by European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) Long-Term Fellowship ALTF290-2017; A.A. by NIH Grants R01 DK059600 and P30 DK079337; and S.B. by NIH Grant K01 DK103931.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1822024116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira A, et al. Sickle hemoglobin confers tolerance to Plasmodium infection. Cell. 2011;145:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Råberg L, Sim D, Read AF. Disentangling genetic variation for resistance and tolerance to infectious diseases in animals. Science. 2007;318:812–814. doi: 10.1126/science.1148526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis SE, Sullivan DJ, Jr, Goldberg DE. Hemoglobin metabolism in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:97–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sigala PA, Crowley JR, Hsieh S, Henderson JP, Goldberg DE. Direct tests of enzymatic heme degradation by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37793–37807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.414078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orjih AU, Banyal HS, Chevli R, Fitch CD. Hemin lyses malaria parasites. Science. 1981;214:667–669. doi: 10.1126/science.7027441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pamplona A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide suppress the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria. Nat Med. 2007;13:703–710. doi: 10.1038/nm1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouveia Z, et al. Characterization of plasma labile heme in hemolytic conditions. FEBS J. 2017;284:3278–3301. doi: 10.1111/febs.14192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gozzelino R, et al. Metabolic adaptation to tissue iron overload confers tolerance to malaria. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:693–704. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsh K, et al. Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1399–1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sypniewska P, et al. Clinical and laboratory predictors of death in African children with features of severe malaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15:147. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0906-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz LAB, Barral-Netto M, Andrade BB. Distinct inflammatory profile underlies pathological increases in creatinine levels associated with Plasmodium vivax malaria clinical severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nath KA, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid, protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:267–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI115847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zarjou A, et al. Proximal tubule H-ferritin mediates iron trafficking in acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4423–4434. doi: 10.1172/JCI67867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalko E, et al. Multifaceted role of heme during severe Plasmodium falciparum infections in India. Infect Immun. 2015;83:3793–3799. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00531-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seixas E, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 affords protection against noncerebral forms of severe malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15837–15842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903419106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins DF, et al. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3810–3820. doi: 10.1172/JCI30487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider DS. Tracing personalized health curves during infections. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parada E, et al. The microglial α7-acetylcholine nicotinic receptor is a key element in promoting neuroprotection by inducing heme oxygenase-1 via nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1135–1148. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins R, et al. Heme drives hemolysis-induced susceptibility to infection via disruption of phagocyte functions. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1361–1372. doi: 10.1038/ni.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenstein RS, Garcia-Mayol D, Pettingell W, Munro HN. Regulation of ferritin and heme oxygenase synthesis in rat fibroblasts by different forms of iron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:688–692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darshan D, Vanoaica L, Richman L, Beermann F, Kühn LC. Conditional deletion of ferritin H in mice induces loss of iron storage and liver damage. Hepatology. 2009;50:852–860. doi: 10.1002/hep.23058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balla G, et al. Ferritin: A cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18148–18153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen R, et al. A central role for free heme in the pathogenesis of severe sepsis. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:51ra71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weis S, et al. Metabolic adaptation establishes disease tolerance to sepsis. Cell. 2017;169:1263–1275.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alam J, et al. Nrf2, a Cap’n’Collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26071–26078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pietsch EC, Chan JY, Torti FM, Torti SV. Nrf2 mediates the induction of ferritin H in response to xenobiotics and cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2361–2369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210664200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki T, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Toward clinical application of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:166–174. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee PJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5375–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW, Galy B. A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell. 2017;168:344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soares MP, Hamza I. Macrophages and iron metabolism. Immunity. 2016;44:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theurl I, et al. On-demand erythrocyte disposal and iron recycling requires transient macrophages in the liver. Nat Med. 2016;22:945–951. doi: 10.1038/nm.4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J, et al. Strain-specific innate immune signaling pathways determine malaria parasitemia dynamics and host mortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E511–E520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316467111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fervenza FC, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 and ferritin in the kidney in warm antibody hemolytic anemia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:972–977. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nath KA, et al. Heme protein-induced chronic renal inflammation: Suppressive effect of induced heme oxygenase-1. Kidney Int. 2001;59:106–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Heme oxygenase 1 is required for mammalian iron reutilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10919–10924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yachie A, et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:129–135. doi: 10.1172/JCI4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soty M, Gautier-Stein A, Rajas F, Mithieux G. Gut-brain glucose signaling in energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1231–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cumnock K, et al. Host energy source is important for disease tolerance to malaria. Curr Biol. 2018;28:1635–1642.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.