Significance

In flowering plants, membrane-associated kinases of the BRASSINOSTEROID SIGNALING KINASE (BSK) family are ubiquitous, receptor-associated signaling partners in various receptor kinase pathways, where they function in signaling relay. The Brassicaceae-specific BSK family member SHORT SUSPENSOR (SSP), however, acts as a patterning cue in the zygote, initiating the apical-basal patterning process in a signal-like manner. The SSP protein has lost a regulatory, intramolecular interaction and activates the MAPKKK YODA signaling pathway constitutively, in principle, enabling the protein to initiate embryonic patterning without receptor activation. We further show that the BSK family members BSK1 and BSK2, both conserved in flowering plants, activate the same signaling pathway in parallel to SSP and might constitute remnants of an older, canonical signaling pathway still active in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, evolution, MAP kinase signaling, embryogenesis, BRASSINOSTEROID SIGNALING KINASE

Abstract

In flowering plants, the asymmetrical division of the zygote is the first hallmark of apical-basal polarity of the embryo and is controlled by a MAP kinase pathway that includes the MAPKKK YODA (YDA). In Arabidopsis, YDA is activated by the membrane-associated pseudokinase SHORT SUSPENSOR (SSP) through an unusual parent-of-origin effect: SSP transcripts accumulate specifically in sperm cells but are translationally silent. Only after fertilization is SSP protein transiently produced in the zygote, presumably from paternally inherited transcripts. SSP is a recently diverged, Brassicaceae-specific member of the BRASSINOSTEROID SIGNALING KINASE (BSK) family. BSK proteins typically play broadly overlapping roles as receptor-associated signaling partners in various receptor kinase pathways involved in growth and innate immunity. This raises two questions: How did a protein with generic function involved in signal relay acquire the property of a signal-like patterning cue, and how is the early patterning process activated in plants outside the Brassicaceae family, where SSP orthologs are absent? Here, we show that Arabidopsis BSK1 and BSK2, two close paralogs of SSP that are conserved in flowering plants, are involved in several YDA-dependent signaling events, including embryogenesis. However, the contribution of SSP to YDA activation in the early embryo does not overlap with the contributions of BSK1 and BSK2. The loss of an intramolecular regulatory interaction enables SSP to constitutively activate the YDA signaling pathway, and thus initiates apical-basal patterning as soon as SSP protein is translated after fertilization and without the necessity of invoking canonical receptor activation.

The organization of complex multicellular bodies is driven by the sequential creation of cells with distinct properties. In higher plants, this process generally starts soon after fertilization, as the division of the zygote is typically asymmetrical, giving rise to daughter cells with different developmental fates (1). Early development of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana and other members of the Brassicaceae family proceeds in a strictly stereotypic pattern, making it easy to follow the fate of individual cells (1). The smaller apical daughter of the Arabidopsis zygote always forms the embryo proper, while the larger basal cell develops into a filamentous support structure, called the suspensor, that connects the developing embryo with maternal seed tissue and serves as a conduit for nutrients and hormones (2). Only the uppermost cell of the suspensor contributes to the embryo, forming part of the embryonic root pole, while all other suspensor cells remain extraembryonic (3). Thus, the zygotic division already marks embryonic vs. extraembryonic cell fate.

In other plant species, however, plant embryos often do not show a well-defined boundary between embryonic and extraembryonic cell identity based on morphological criteria. In some cases of grasses, the patterning process even seems to take place at later developmental stages involving a larger number of cells (4). The stereotypic, early patterning of Brassicaceae embryos creates all essential cell types by a minimum of cell divisions, and might therefore be an adaption to the rapid life cycle typically seen in many species of this family.

Genetic evidence has established that apical-basal patterning in Arabidopsis is controlled by MAP kinase signaling. The MAPKK kinase YODA (YDA) acts in the zygote to promote elongation and embryonic polarity (5). Loss of YDA activity leads to more equal zygote divisions, and derivatives of the basal daughter cell subsequently typically adopt an embryonic division pattern that can result in embryos without a recognizable suspensor (6). Similar effects are observed with loss of the MAPK kinases MKK4 and MKK5 or the MAP kinases MPK3 and MPK6 (7, 8). Engineered constitutive activity of YDA leads to supernumerary suspensor cells and, in many cases, produces filamentous structures without a recognizable embryo (6). It has been concluded that signaling through the YDA MAP kinase cascade is setting up apical-basal polarity in the early embryo and promotes extraembryonic differentiation.

Postembryonically, mutant yda seedlings are dwarfed and display various morphological alterations in comparison to wild type, reflecting the involvement of the MAP kinase cascade in a number of other signaling events (9, 10). In epidermal patterning, for example, YDA acts as part of a canonical signaling pathway downstream of a receptor complex that includes receptor kinases of the ERECTA family (ERf) and the SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE (SERK) family to regulate spacing of stomata in the epidermis of leaves (11). However, the available evidence suggests that YDA activation in the zygote may involve different mechanisms.

In the context of the embryo, YDA is, at least in part, activated by the action of a membrane-associated pseudokinase called SHORT SUSPENSOR (SSP) (12). SSP transcripts accumulate specifically in the two sperm cells in the pollen, and SSP protein has only been detected transiently after fertilization in the zygote, presumably translated from inherited, previously translationally silent paternal transcripts (12). Overexpression of SSP can activate the YDA MAP kinase cascade in other tissues; by analogy, it has been proposed that SSP protein acts in a signal-like manner to trigger YDA activation in the zygote (12).

SSP is a member of the multigene family of BRASSINOSTEROID SIGNALING KINASE (BSK) genes. BSKs function as cytoplasmic signaling partners in various SERK-dependent receptor kinase pathways involved in plant growth, innate immunity, and abiotic stress response (13–15). BSK proteins are thought to be phosphorylated upon receptor activation and have been proposed to recruit downstream signaling components in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (16, 17). Most of the BSK genes seem to have overlapping functions, as obvious phenotypic alterations have only been described for higher order mutants (18). Interestingly, SSP is of very recent evolutionary origin, splitting from its sister gene BSK1 about 23 million years ago in the last whole-genome duplication within the Brassicaceae (19). While BSK1 evolved under purifying selection, SSP has diverged considerably from the common ancestor; in addition, BSK1 remains ubiquitously expressed throughout plant development, like most BSK genes, whereas SSP expression has become tightly restricted to the male germ line (12, 19). How can the evolution of SSP from an ancestral role similar to other BSK genes (general, functionally redundant signaling components in receptor kinase pathways) to a factor providing patterning cues in early embryonic development be rationalized?

Here, we show that BSK1, the sister gene of SSP, together with BSK2, a second close paralog within the same family, act in parallel to SSP upstream of YDA in the zygote and early embryo, and might therefore constitute remnants of an older prototype of the embryonic YDA pathway. Furthermore, we demonstrate that BSK1 and BSK2 also take part in YDA-dependent signaling events outside the embryo, determining plant growth, inflorescence architecture, and stomatal patterning. A detailed comparison between the biochemical properties and structure of BSK1 vs. SSP reveals that SSP likely neofunctionalized through loss of negative regulation. By acquiring properties that enable constitutive activation of the YDA pathway, SSP can now directly link the onset of zygotic transcription after the fertilization event to the onset of apical-basal pattering.

Results

BSK1 and BSK2 Contribute to Embryonic Patterning, Independent of SSP.

Embryos mutant for ssp display a significantly less severe phenotype than yda mutant embryos (12) (Fig. 1), implying that other factors contributing to activation of the YDA MAP kinase cascade in the zygote should exist. BSK1 may be such a factor since it shares a recent evolutionary origin with SSP (19) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). However, bsk1 single mutants did not show any obvious differences from wild-type embryos (Fig. 1A). Transcriptome datasets of early embryos revealed high expression levels of BSK2, a close homolog of BSK1 (20, 21) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). These findings could be confirmed by reporter gene analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B–E), and we therefore included bsk2 mutants in our studies. While bsk2 embryos were indistinguishable from wild type, the phenotype of bsk1 bsk2 double mutants was strikingly reminiscent of ssp (12) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Functional importance of BSK family kinases in early embryogenesis. (A) Nomarsky images of transition-stage embryos in whole-mount cleared seeds of wild-type Col-0, yda, bsk1-2, bsk2-2, and ssp-2 single mutants, as well as bsk1 bsk2 double mutants (b1 b2) and bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants (b1 b2 ssp). (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (B) Box plot diagram of suspensor length measurements for >100 embryos. The total number of analyzed embryos is depicted above the x axis. The box plot diagram shows the median as center lines, and the 25th and 75th percentiles are indicated by box limits. Whiskers show 1.5× interquartile distance. Outliers are represented by dots. Statistically significant differences from wild type were determined by the Mann–Whitney U test (**P < 0.001; *P < 0.01). Statistically significant differences in other pairwise comparisons are indicated by brackets. (C) Nomarsky images of embryos at the one-cell stage in whole-mount cleared seeds. The average sizes of the apical (yellow) and basal (green) daughter cells with the SD and number of analyzed embryos are given below the image. Furthermore, significant differences in pairwise comparisons to the indicated reference (Ref) determined by the Mann–Whitney U test (*P < 0.001) are indicated below the image (gray). Apical cells are false-colored in yellow, and basal cells are shown in green. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

The first observable effect caused by mutations in YDA signaling is drastically reduced elongation of the zygote (6). The bsk1 bsk2 double mutants similarly exhibit reduced zygotic cell growth, which results in a smaller basal cell in comparison to wild type after the first zygotic division (Fig. 1C). Again, similar to other mutations in the pathway, the basal cell of bsk1 bsk2 embryos produces a suspensor of reduced length (Fig. 1 A and B), frequently showing aberrant divisions in a vertical plane (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The phenotype of ssp bsk1 bsk2 triple-mutant embryos is stronger than the phenotype of either ssp single or bsk1 bsk2 double mutants (Fig. 1), suggesting an additive effect, and only slightly weaker than the phenotype of yda mutants (Fig. 1 A and B).

BSK1 and BSK2 Act in Postembryonic Signaling Events.

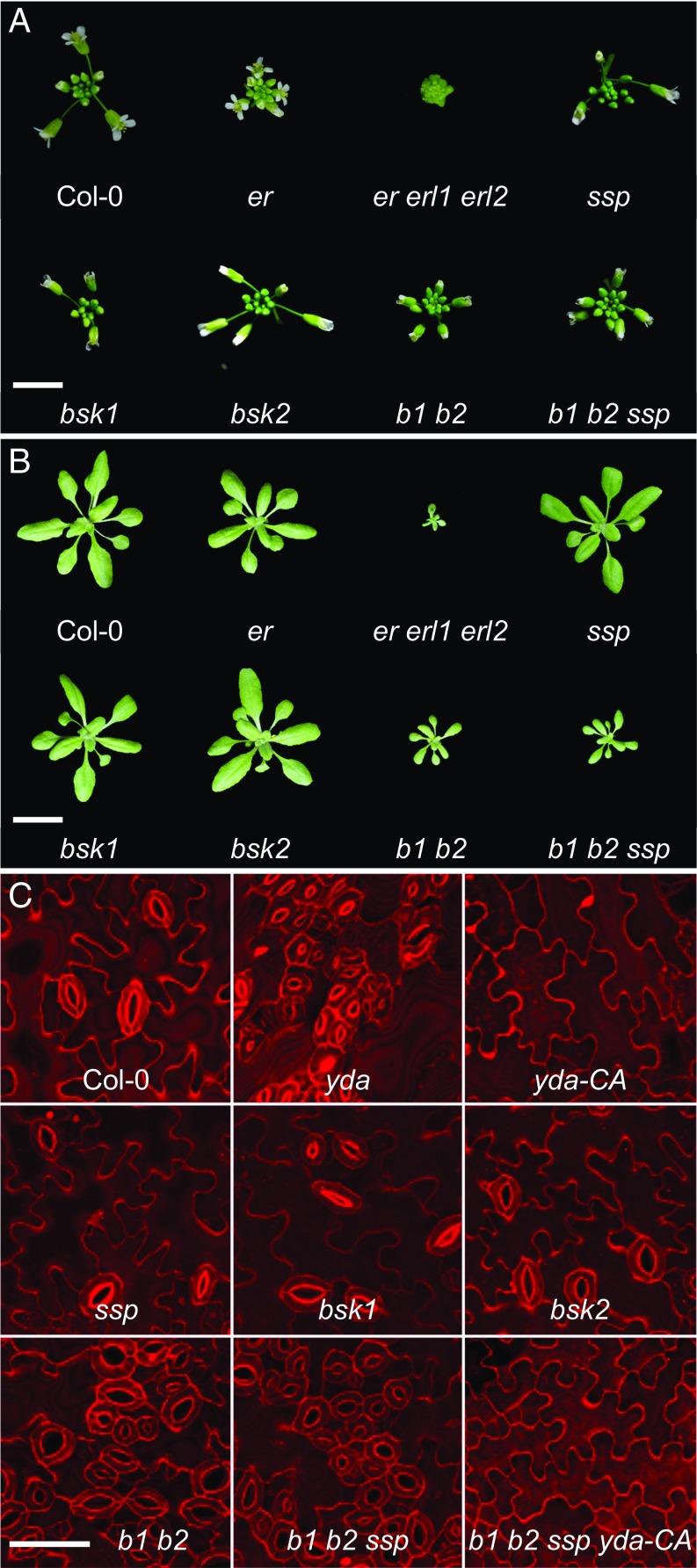

Since BSK1 and BSK2 are ubiquitously expressed throughout plant development [determined by AtGenExpress (22)], we next investigated whether they act in YDA-dependent signaling events outside of the embryo. YDA signaling is, among other developmental decisions, necessary for rosette growth and inflorescence architecture, as well as epidermal patterning. In all three instances, YDA acts downstream of receptor kinases of the ERf: Mutations in ERf/YDA pathway components result in severely dwarfed plants with smaller rosette leaves and more compressed inflorescences, as well as massive stomata clustering (23–25). Single mutants of bsk1 or bsk2 display no obvious alterations in these traits (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C). In contrast, the bsk1 bsk2 double mutants recapitulate the phenotype of yda or erf mutants, displaying strikingly smaller rosettes (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), more compact inflorescences (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), and clustered stomata (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). These observations indicate that BSK1 and BSK2 might be general signaling components in YDA-dependent pathways. The additional loss of SSP in the bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutant does not result in any further enhancement of postembryonic defects (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C), confirming that SSP function is confined to the embryo.

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic analysis of YDA-dependent plant development. (A) Inflorescence development of wild-type Col-0 in comparison to single-, double-, and triple-mutant combinations of ERf kinases and BSK family kinases. The bsk1 bsk2 double mutant (b1 b2) and bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutant (b1 b2 ssp) show more compact inflorescences very similar to erecta (er) single mutants and erecta erecta-like1 erecta-like2 (er erl1 erl2) triple mutants. (Scale bar: 5 mm.) (B) Rosette leaves at the time of bolting. No obvious difference in rosette diameter can be seen in bsk1-2, bsk2-2, or ssp single mutants in comparison to wild type. The bsk1 bsk2 double mutant, however, shows a reduced rosette size similar to plants with reduced ERf receptor signaling (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). (Scale bar: 2 cm.) (C) Epidermal phenotype of 10 d-old seedlings of wild-type Col-0, bsk1, bsk2, ssp, bsk1 bsk2 double mutants (b1 b2), and bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants (b1 b2 ssp), as well as bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants carrying a constitutively active variant of yda (b1 b2 ssp yda-CA). Loss-of-function yda mutants and a constitutively active variant of YDA (yda-CA) are shown as controls. (Scale bar: 50 μm.)

BSK1 and BSK2 Act Genetically Upstream of YDA.

BSK family kinases are membrane-associated proteins, and genetic and biochemical evidence showed that SSP acts upstream of YDA in a linear pathway (12, 26). To test the idea that BSK1 and BSK2 similarly act upstream of the YDA MAP kinase cascade, we created bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants that additionally carry a constitutively active version of YDA (YDA-CA). The YDA-CA transgene rescues the yda loss-of-function mutant and creates a strong gain-of-function effect, resulting in a leaf epidermis devoid of stomata and consisting almost entirely of pavement cells (9) (Fig. 2C). The YDA-CA variant was not only able to rescue the genetic defects in stomatal patterning of bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants but displayed an epidermal phenotype highly similar to YDA-CA seedlings (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). This epistatic behavior of YDA-CA strongly argues for a function of BSK1 and BSK2 in the ERf/YDA pathway and indicates that BSK1 and BSK2 act genetically upstream of YDA.

We could furthermore observe a similar epistatic behavior of YDA-CA in bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple-mutant embryos that were genetically rescued by a YDA-CA transgene (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This further supports the notion that BSK1 and BSK2 act upstream of YDA and might be rather ubiquitous constituents of YDA-dependent signaling pathways.

BSK1 Cannot Compensate for the Loss of SSP in the Zygote and Early Embryo.

Our genetic analysis revealed that SSP and BSK1/BSK2 contribute additively to zygote elongation and suspensor development. SSP mRNA is supplied paternally by the pollen (12), suggesting the possibility that SSP may mediate early activation of the YDA pathway, before BSK1/BSK2 proteins may be able to accumulate. To test the hypothesis that the specific contribution of SSP to early development results from pollen-specific expression, we expressed SSP and BSK1 genomic coding regions under control of the male germ line-specific MGH3 promoter and the SSP promoter, and tested the ability of these constructs to complement the ssp mutant phenotype (Figs. 3 and 4). Surprisingly, none of the pMGH3::BSK1 or pSSP::BSK1 lines showed genetic rescue of the ssp loss-of-function phenotype, while all pMGH3::SSP or pSSP::SSP transgenic lines used for the analysis rescued the ssp embryonic phenotype. This clearly indicates that SSP and BSK1 proteins differ in their potential to activate the embryonic YDA pathway and implies that neofunctionalization of SSP did not merely involve a simple change in expression pattern but also changes to the protein properties.

Fig. 3.

Genetic rescue of ssp mutants by sperm-specific BSK gene expression. A box plot diagram of suspensor size measurements 75 h after pollination is shown. Homozygous transgenic lines carrying pMGH3::SSP or pMGH3::BSK1 in a bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple-mutant background were used as pollen donors to pollinate wild-type Col-0 plants. Control Col-0 and bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants were used as pollen donors in parallel experiments. Without genetic rescue, the paternal effect of the mutant ssp allele causes reduced suspensor size in heterozygous embryos. The box plot diagram shows the median as center lines, and the 25th and 75th percentiles are indicated by box limits. Whiskers show 1.5× interquartile distance. Outliers are represented by dots. The total number of embryos for each genotype is given above the x axis. Statistically significant differences from the control crosses with homozygous bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutants as pollen donors are indicated by asterisks (Mann–Whitney U test: *P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

SSP-specific properties can be mapped to the C-terminal TPR motif. (A) To map the structural features underlying the functional difference between the SSP and BSK1 protein, chimeric constructs (described in Materials and Methods) were tested for their ability to genetically rescue the ssp mutant phenotype. For each construct, 12 independent transgenic lines were analyzed for genetic rescue of the embryonic ssp phenotype (>100 embryos each line) in comparison to a full-length SSP rescue construct as a positive control and a nonfunctional SSP construct [SSP G2 > A (12)] as a negative control. Functional protein domains/motifs are depicted as larger rectangular boxes. A, kinase activation loop; K, kinase domain; M, myristoylation motif; T, TPR domain. Each predicted TPR repeat is shown as an individual rectangular box, and the first cryptic repeat is indicated by a dashed line. SSP sequences are depicted in gray, and BSK1 sequences are depicted in white. (B) Genetic rescue of ssp mutants based on morphological criteria by expression of chimeric SSP and BSK1 variants shown in A under control of the SSP regulatory sequences. The bar graph shows the number of wild-type embryos as an average percent value with the SD for 12 independent transgenic lines for each construct. Statistically significant differences from the negative control (ssp) are indicated (determined by χ2 test: *P < 0.0001) (details of the analysis and statistical test are provided in Dataset S1, and the heritability of these traits is shown in Dataset S2). (C) Transcript levels of CYP82C in Arabidopsis protoplasts in response to the expression of SSP and BSK1 and chimeric versions determined by qRT-PCR. As controls, a constitutively active variant (YDA-CA) and a nonfunctional version of YDA (YDA-KD) were used. Transcript levels were normalized to EF2 expression as a reference. Expression levels are given as relative values, with the negative control (YDA-KD) arbitrarily set to 1. Significant differences from the negative control (YDA-KD) are indicated (Student’s t test: *P < 0.05).

SSP Expression Constitutively Activates Downstream Target Genes.

Ectopic overexpression of SSP in seedlings evokes a strong gain-of-function effect similar to constitutively active versions of YDA (12). Most strikingly, this phenotype manifests itself in an almost complete lack of stomata on the leaf surface (9, 12). In contrast, similar experiments with BSK1 were previously reported to have little or no effect on plant architecture (27). To corroborate and refine these findings, we examined the effect of overexpressing BSK1 from the strong, ubiquitously active CaMV 35S promoter on stomata density in detail and found no obvious changes compared with wild type (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The growth defects and the clustered stomata phenotype of the bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutant were rescued to various degrees by the p35S::BSK1 transgene in all transgenic lines tested, indicating that the transgene is functional. Furthermore, these plants displayed a wild-type growth phenotype, and no obvious gain-of-function effects were recognizable. This suggests that, in contrast to SSP, the presence of the BSK1 protein alone is not sufficient to hyperactivate the YDA pathway, despite being an integral part of this pathway. To directly test the hypothesis that SSP, but not BSK1, overexpression leads to strong activation of YDA target genes, we monitored the transcription of EPF2 in suspension culture-derived protoplasts (Fig. 5A). The EPF2 gene is a target of the ERf/YDA pathway, it encodes one of the ligands of ERf receptors (28), and its expression is negatively regulated by the YDA MAP kinase cascade (29). As predicted from previous reports, the expression of YDA-CA led to down-regulation of EPF2 expression in comparison to samples in which an inactive, kinase-dead (KD) version of YDA (YDA-KD) was expressed (Fig. 5A). Expression of BSK1 had no detectable effect on EPF2 expression, supporting the notion that the signaling activity of BSK1 is predominantly regulated by receptor-mediated phosphorylation (27) rather than protein abundance. In stark contrast, SSP expression leads to strong down-regulation of EPF2 in a similar way as in samples expressing YDA-CA (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Activation of the ERf/YDA pathway by ectopic SSP expression. (A) Transcript levels of EPF2 in Arabidopsis protoplasts in response to expression of SSP and BSK1 determined by qRT-PCR. As controls, a constitutively active variant (YDA-CA) and a nonfunctional version of YDA (YDA-KD) were used. Transcript levels were normalized to EF2 expression as a reference. Expression levels are given as relative values with the negative control (YDA-KD) arbitrarily set to 1. Significant differences from the negative control (YDA-KD) are indicated by asterisks (Student’s t test: *P < 0.05). (B) Phosphorylation of MPK3 and MPK6 in response to YDA activation detected by Western blotting with a phosphorylation-sensitive antibody against the activation loop of both kinases. As loading controls, phosphorylation-independent antibodies against MPK6 and tubulin were used. Note that the polyclonal antibody against MPK6 also detects MPK3 (black arrowhead). The MPK3 and MPK6 proteins have expected sizes of 42.7 kDa (black arrowhead) and 45.1 kDa (white arrowhead), respectively. The bar graph gives the relative amount of phosphorylated MPK6 in relation to total MPK6 as inferred by the signal intensity of the corresponding Western blots. Average values and SDs of three Western blots are shown. Significant differences from the negative control (YDA-KD) are indicated (Student’s t test: *P < 0.05).

In this overexpression experiment, SSP appeared to activate the YDA MAP kinase cascade in a manner that did not involve the canonical ligands of the pathway. To test this idea, we transiently expressed BSK1 and SSP in Arabidopsis protoplasts and monitored the activation of MPK3 and MPK6 using a phosphorylation-specific antibody against the activation loop (Fig. 5B). As a positive control, we expressed YDA-CA and observed a strong increase in signal intensity compared with cells expressing the nonfunctional YDA-KD. The expression of BSK1 did not noticeably influence the amount of phosphorylated MPK3 or MPK6, while the expression of SSP led to a strong increase in activated MPK3 and MPK6 (Fig. 5B). The overall MPK6 abundance, as measurable with antibody binding independent of phosphorylation status, did not change in any of these experiments.

Taken together, our data strongly suggest that the SSP protein is capable of triggering YDA-dependent signaling. In this scenario, SSP would be able to initiate downstream YDA-dependent signaling without canonical receptor activation.

Constitutive Signaling Activity Due to Loss of Intramolecular Interaction.

SSP has been described as a quite unusual BSK family member with a conspicuously shorter activation loop in comparison to other BSK family proteins (19). SSP has been regarded as a pseudokinase (12); however, kinase activity assays have not been performed. To test if the differences between SSP and BSK1 can be attributed to increased kinase activity of SSP, we purified YDA, SSP kinase, and BSK1 kinase after heterologous expression in Escherichia coli and performed kinase activity assays (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). We used full-length YDA as a positive control, which showed readily detectable ATP turnover. In contrast to YDA, however, we could not detect kinase activity for SSP or BSK1. While the ATP turnover for SSP did not differ at all from the negative control, there was a very weak but statistically not significant increase in ATP turnover for BSK1 (not visible in SI Appendix, Fig. S7). These results are in agreement with previous reports indicating that kinase activity is not necessary for SSP function and suggest that BSK family proteins might function primarily by recruiting downstream signaling components (12, 16, 19). As we cannot detect any kinase activity for SSP, the constitutive activation of downstream signaling components has to be explained by a different mechanism.

BSK proteins are generally regulated by phosphorylation (27); in the case of rice OsBSK3, it has been shown that phosphorylation breaks a direct and negative auto-regulatory interaction between the C-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) motif and the central kinase domain (30), liberating the protein to recruit downstream signaling partners. Given the close structural similarity of BSK proteins, this mode of regulation may well be conserved within the family, and we thus wanted to determine whether similar intramolecular interactions could be detected with Arabidopsis BSK1 and SSP, respectively. In a yeast two-hybrid interaction assay, the isolated TPR domain of BSK1 indeed showed clear interaction with its kinase domain. Strikingly, this interaction could not be observed for the closely related SSP TPR domain when tested with the SSP kinase domain (Fig. 6A), despite expression of the SSP TPR domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). We independently confirmed these results in plant cells by transiently expressing the TPR and kinase domains of BSK1 and SSP, respectively, as fusion proteins for ratiometric bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays (rBiFCs) (31) in tobacco leaves (Fig. 6B). For the most part, the rBiFC assay corroborated our observations in the yeast two-hybrid assay. With the rBiFC assay, we could not detect any interaction of the SSP TPR domain with its kinase domain, while the corresponding TPR domain of BSK1 interacts with the BSK1 kinase domain. In contrast to the yeast experiment, we could also detect an interaction of the BSK1 TPR domain with the SSP kinase domain, possibly indicating that changes within the SSP TPR domain are responsible for neofunctionalization.

Fig. 6.

SSP has lost the competence for intramolecular interaction. (A) Yeast two-hybrid assay to test for interaction between the TPR and kinase domains of SSP and BSK1. Serial dilutions of yeast cells containing the GAL4-DNA binding domain (BD) fused to the TPR domain of SSP or BSK1 plus the GAL4 activation domain (AD) fused to the kinase domains of SSP or BSK1, respectively, were dropped on vector-selective [complete supplement medium without leucine and tryptophan (CSM L- W-)] and interaction-selective medium (CSM L- W- H- Ade-). Growth was monitored after 3 d at 30 °C. pGADT7 empty vector was used as a negative control (“vector”). (B) Interaction tests using rBiFC. (Top) Confocal images of transiently transformed N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells representing the median value of RFP and YFP fluorescence for each experiment are shown. (Bottom) Box plot diagram depicts the ratio of the mean fluorescence of YFP against RFP from 25 different, randomly chosen leaf sections. Center lines of boxes represent the median, with outer limits at the 25th and 75th percentiles. Notches indicate 95% confidence intervals. Tukey whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile ratio.

The lack of intramolecular, regulatory interaction in SSP might be a simple explanation for its property to evoke a constitutive signaling response. SSP has been described to directly bind the downstream MAPKKK YDA (26), while a direct interaction has been reported for BSK1 with the MAPKKK MKKK5 (32). To rule out the possibility that SSP differs from BSK1 in its ability to directly interact with YDA, we tested the interaction of SSP and BSK1 with different parts of the YDA protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). In a yeast two-hybrid assay, the TPR motifs of SSP and BSK1 showed binding to the YDA kinase domain, while no interaction with the N-terminal region of YDA could be detected.

These results further support our genetic data and indicate that BSK1 and SSP are both integral parts of YDA-dependent signaling pathways and can both directly interact with YDA. According to the model of regulation by negative intramolecular interaction, the lack of affinity between the SSP TPR and kinase domains may provide a mechanistic basis for the constitutive activation of the YDA pathway evoked by the SSP protein. To explore this possibility and to map SSP-specific protein properties, we expressed chimeric versions of the SSP gene, where various parts of the coding regions had been replaced by their BSK1 counterparts under the control of the SSP promoter in the ssp mutant background, and monitored the genetic rescue of mutant phenotypes (Fig. 4 A and B). BSK1 has been shown to be phosphorylated within the activation loop, and this site of phosphorylation is absent in SSP (19). It would therefore be conceivable that negatively charged amino acids in the short SSP activation loop mimic constitutive phosphorylation. However, a chimeric BSK1 variant that carries the SSP activation loop did not adopt SSP-like properties, whereas SSP variants with a BSK1 activation loop behaved like the native SSP protein in the genetic rescue experiment, suggesting that the activation loop does not determine the specific property of the SSP protein. An SSP kinase domain paired with a BSK1 TPR motif was also not functional in rescuing the embryonic ssp phenotype, whereas a BSK1 kinase domain fused to an SSP TPR motif retained the ability to rescue ssp-2 mutants. These results demonstrate that, indeed, the structural determinants underlying the different activities of SSP and BSK1 proteins can be largely mapped to the TPR motif. By embedding individual repeat units of BSK1 into an SSP background, we could further show that the third and fourth repeat units of the TRP motif are interchangeable, whereas the presence of the first, cryptic repeat unit or the second repeat unit of BSK1 abolished the function of the chimera. The results clearly demonstrate that the specific signaling property of SSP relies strongly on the SSP TPR motif, which cannot be functionally replaced by the BSK1 TPR domain. Furthermore, neither the activation loop nor the entire SSP kinase domain was sufficient to rescue the ssp defects when positioned in the context of the BSK1 protein.

According to our model, the loss of intramolecular interaction would be responsible for the SSP-specific protein properties. The genetic rescue experiments now indicate that this feature can be largely mapped to the TPR domain. One would therefore assume that the ability to evoke a constitutive signaling response in YDA-dependent signaling pathways can also be mapped to the SSP TPR motif. To test this hypothesis, we used chimeric versions of BSK1 and SSP in a protoplast transient expression system and monitored their effect on YDA-dependent target gene expression (Fig. 4C). CYP82C is transcriptionally up-regulated in protoplasts in response to YDA-CA expression. Expression of full-length SSP similarly led to a strong increase of CYP82C transcripts, as observed with constitutively active YDA-CA (Fig. 4C). As seen for EPF2 expression, full-length BSK1 expression, on the other hand, has no detectable effect on CYP82C transcript levels. When testing chimeric constructs, BSK1 protein that carries the SSP TPR motif causes the same up-regulation of target gene expression as full-length SSP and constitutively active YDA-CA. The chimeric SSP protein that harbors a BSK1-derived TPR motif, on the other hand, did not cause activation of CYP82C expression. In agreement with our model, only protein variants that cause a constitutive signaling response were also able to rescue the genetic defects of ssp mutants (Fig. 4).

Taken together, our data strongly suggest that the SSP protein causes a nonregulated, constitutive activation of YDA-dependent signaling pathways that is most likely the consequence of loss of inhibitory, intramolecular interaction previously demonstrated for BSK family proteins. This lack of regulation, however, can presumably be tolerated by the plant because of the tightly controlled expression pattern of SSP that confines the SSP protein to the early embryo (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). According to this model, we would predict that prolonged expression of SSP in the early embryo should evoke gain-of-function phenotypes. To test this hypothesis, we expressed a functional SSP-YFP fusion in the early embryo using a GAL4-UAS transactivation system under the control of the ubiquitously active RPS5a promoter. Only in F1 embryos that carried the RPS5a driver as well as the pUAS::SSP-YFP effector constructs could we observe embryos with supernumerary suspensor cells and structures entirely lacking a recognizable proembryo, reminiscent of embryos that carry a constitutively active variant of YDA (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Embryos that carried only the driver line or the effector line did not show any obvious differences from wild-type embryos. Furthermore, transactivation of BSK1 in the early embryo under control of the same expression system did not lead to any obvious morphological changes in comparison to control plants. Prolonged expression of SSP in the embryo therefore evokes a similar gain-of-function phenotype as observed when ectopically expressed in the leaf epidermis, strongly arguing in favor of SSP evoking a constitutive signaling response of YDA-dependent signaling pathways.

Taken together, we could show that SSP exhibits a nonregulated, constitutive signaling activity that is most likely the consequence of loss of inhibitory, intramolecular interaction previously demonstrated for BSK family proteins. Tightly controlled expression of SSP, on the other hand, might make posttranslational regulation unnecessary.

Discussion

BSK family proteins have been described to fulfill a role as receptor-associated cytoplasmic kinases in a similar manner as, for example, the interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinases (33). Due to neighboring kinases in the respective receptor complex, these kinases often do not need kinase activity for their function (34, 35). Based on the protein structure of the Arabidopsis BSK8 kinase domain, it was proposed that, in general, BSK family kinases are pseudokinases (17). Our kinase assays with BSK1 and SSP kinase domains support this notion. The regulated function of BSK proteins might therefore manifest itself in the passing of signal information by phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of downstream signaling components that, in turn, can be phosphorylated by nearby kinases (16, 30). For BSK1, however, kinase activity in the context of MKKK5 phosphorylation has recently been reported using an antibody against phosphate moieties (32). In agreement with the published data for BSK8 (17) and SSP (12), but in contrast to the previous report regarding BSK1 (32), we could not detect kinase activity for isolated kinase domains of BSK1 and SSP. As we could observe a low but statistically not significant turnover of ATP in the sample containing BSK1, very low kinase activity at our detection limit cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, as our experiments were performed with isolated kinase domains, we cannot exclude the possibility that BSK family proteins possess kinase activity in their native form. In the context of SSP-dependent YDA activation, however, any potential differences in kinase activity between SSP and BSK1 cannot explain the different behavior of these proteins, as swapping kinase domains or the activation loop between SSP and BSK1 in chimeric constructs did not have any effect, while the SSP-specific activation of YDA-dependent target genes depended on the SSP C-terminal TPR motif.

BSK family proteins have been functionally described in the context of brassinosteroid signaling in combination with the receptor kinases BRI1 and BAK1/SERK3 regulating plant growth (16, 27). In this context, several BSKs act in a genetically redundant manner, while BSK3 seems to be more prominently involved (18). BSK1 also interacts with the receptor kinases FLS2 and BAK1/SERK3 in the context of innate immunity responses (14, 36). For BSK5, a role in response to abiotic stress has been postulated (15). Our data now introduce BSK1 and BSK2 as signaling partners of the ERf/YDA signaling pathway, a pathway in which coreceptors of the SERK family also participate (11). Therefore, BSK family kinases could well be rather general downstream signaling partners of SERK-dependent receptor complexes in various (MAP kinase) signaling pathways. Several other receptor pathways with related leucine-rich receptor kinases, such as HAE, HSL2, PXY, and EMS1, have been described as SERK-dependent, and some of them rely on a MAP kinase cascade, including MPK6 (37–39). It will be interesting to see if BSK family kinases also play a role in these pathways.

In the context of brassinosteroid signaling, BSK genes supposedly act in a genetically redundant manner (18). It is therefore quite surprising, and in contrast to previous reports, that bsk1 and bsk2 double mutants show strong growth defects. This is probably due to the allele choice in previous studies, as the bsk1-3 (SAIL_140_C04) allele is not a null allele (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), while our work was carried out with the bsk1-2 allele, which does not produce functional BSK1 protein (13) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Interestingly, the bsk1-2 bsk2-2 double mutant shows an epidermal phenotype with clusters of stomata almost as dramatic as yda loss-of-function mutants (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Therefore, the other 10 BSK genes might play only a minor role in the context of ERf/YDA signaling and might be more prominently involved in other SERK-dependent signaling pathways. In a similar manner, the bsk1 bsk2 ssp triple mutant shows aberrant suspensor development very similar to yda loss-of-function mutants. Again, this would argue in favor of functional specificity of different BSK genes.

BSK1 and BSK2 seem to be evolutionarily conserved as they can be found in basal angiosperms such as Amborella trichopoda (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). SSP orthologs, however, only exist in members of the Brassicaceae family and evolved during the last whole-genome duplication of the core Brassicaceae as a duplicate of BSK1 (19). The involvement of BSK1 and BSK2 in the embryonic YDA pathway, as well as the ERf/YDA pathway, therefore most likely reflects an ancestral state, with SSP being an embryo-specific innovation of the Brassicaceae. The loss-of-function phenotype of the bsk1 bsk2 double mutant, on the other hand, demonstrates that BSK1 and BSK2 still contribute to YDA activation in the early embryo. This suggests that a more ancient prototype of YDA activation, possibly via a receptor complex, might still be functional during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. This would also imply that in non-Brassicaceae plants, apical-basal polarity of the zygote could solely rely on BSK1/BSK2-dependent activation of YDA. As many of these plants have embryos with a poorly defined embryo-suspensor boundary quite similar to ssp mutant embryos in Arabidopsis, it would be fascinating to see what consequences introducing a functional SSP gene would have on the early embryonic patterning of these plant species.

SSP contributes to YDA activation in the early Arabidopsis embryo in such a way that it cannot be replaced by BSK1. It has been shown that BSK1 is phosphorylated by BRI1 at the activation loop at serine 231, a residue that is conserved among Arabidopsis BSK proteins, and also in CDG1, a further cytoplasmic kinase targeted by BRI1 (40). In SSP, however, this serine residue is missing and might indicate that SSP relies on a different mode of regulation than the other BSK proteins. Our data suggest that SSP acts like a deregulated, constitutively active variant of BSK1 since the presence of the protein is sufficient to activate the MPK6-dependent MAP kinase cascade and has the same impact on target genes as constitutively active YDA.

Kinases are usually highly regulated proteins and are only activated during signaling events. Constitutively active variants occur only rarely and are often associated with diseases [e.g., human epidermal growth factor receptor mutants are associated with cancer (41)]. In extremely rare cases, acquired constitutive activity might be beneficial and functionally important, as is the case for protein kinase CK2 (42). One possible evolutionary scenario for SSP would be that an initial event confined SSP expression to sperm cells, rendering the duplicated gene functionally irrelevant. In the absence of purifying selection, SSP was then free to accumulate mutations that destroyed regulatory regions of the protein, turning it constitutively active. It was speculated that an in-frame deletion in the activation loop of SSP, which occurred early after the whole-genome duplication and encompasses the BRI1-dependent phosphorylation site of BSK1, might be associated with neofunctionalization (19). Our data, however, demonstrate that the specific properties of SSP reside within the C-terminal TPR domain. Rice OsBSK3 has recently been shown to be negatively regulated through an intramolecular interaction of the kinase domain and the TPR motif. Phosphorylation of the kinase domain activation loop interferes with this interaction and allows the protein to interact with downstream signaling partners (30). Intriguingly, the SSP TPR domain has lost its ability to interact with the kinase domain, providing a possible mechanistic basis for the constitutively active properties of SSP. On the other hand, SSP is capable of direct interaction with YDA, as recently reported (26), and we could show that this is a conserved feature of SSP and BSK1. As described for the interaction of BSK1 and MKKK5 (32), SSP and BSK1 seem to interact with the kinase domain of YDA. Perhaps this simple combination, loss of affinity for the intramolecular interaction with retained affinity for the downstream MAPKK kinase partner, is sufficient for SSP to mediate constitutive activation of the pathway. In this scenario, the phosphorylation sites in the activation loop of the kinase domain would be obsolete and a loss of these sites could well be an evolutionary consequence.

The acquired gain-of-function in the SSP protein facilitates YDA activation as soon as the sperm cell fuses with the egg and SSP protein accumulates in the zygote. We have previously shown that the early YDA activation by SSP is correlated with faster development of the embryo and a more precisely defined embryo-suspensor boundary, both of which are characteristic features of the Brassicaceae (12, 43). Evolution of SSP might therefore be a key innovation that contributes to the reproductive biology of this successful plant family.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions.

All A. thaliana plants used in this study were grown under long-day conditions as described previously (43). The following mutant alleles have been described previously: bsk1-1 (R443 > Q), bsk1-2 (SALK_122120), bsk1-3 (SAIL_140_C04), ssp-2 (SALK_051462), yda-1 (Q443 > STOP), and YDA-CA (6, 12, 14, 18, 44). The bsk2-2 (SALK_001600), er (SALK_066455), erl1 (GK_109G04), and erl2 (GK_486E03) alleles were genotyped using the following gene-specific primers: bsk1-2 LP: ATGAGGTTGCGAGTAGGAT, bsk1-2 RP: CAAAAGCATGACCAATGAGAAG, bsk2-2-F: 5′-GGAAGCGACTGGTGTTGGGAAG-3′, bsk2-2-R: 5′-TGGTCGATCCTTTGCCTCTGA-3′, er-F: 5′-TTCGAAATCGAAAACGGTATG-3′, er-R: 5′-TGTGTGTGAGAAATGGCTCTG-3′, erl1-F: 5′-TTTCCAATCATGATGTTGCAG-3′, erl1-R: 5′-CAAACAATTGCTCCAGCTTTC-3′, erl2-F: 5′-TATCTCCATGGCAACAAGCTC-3′′, erl2-R: 5′-AATGACACATCGCTGAGAAGG-3′, and transfer DNA (T-DNA) primers LBb1.3: 5′-ATTTTGCCGATTTCGGAAC-3′ and GK-LB: 5′-ATATTGACCATCATACTCATTGC-3′, respectively. Multiple mutant combinations were obtained by crossing and PCR-based genotyping of offspring plants.

Plasmid Construction.

For the construction of binary vectors pGreen nos:bar (GIIb) pMGH3::SSP and GIIb pMGH3::BSK1, the genomic region covering the entire coding region was synthesized, avoiding commonly used restriction sites in the coding region. In addition, the intron 3 (SSP) and intron 6 (BSK1) were deleted to allow for PCR-based genotyping of ssp and bsk mutant alleles in the presence of the transgene. The synthesized fragments were cloned into binary vectors containing the MGH3 expression cassette by ligation-based molecular cloning. Expression of the transgene was confirmed for all lines used in the analysis by RT-PCR on cDNA from mature pollen using primers SSP-qF2/SSP-qR2 and BSK1-qF2/BSK1-qR2, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S1). For the p35S::YDA-CA, p35S::YDA-DN, p35S::BSK1, and p35S::SSP expression vectors, coding regions, including restriction sites, were amplified by PCR and transferred into pJIT60 (45) by restriction digest ligation-based cloning. Similarly, for p35S-based expression vectors containing chimeric versions of SSP and BSK1, the chimeric coding region was PCR-amplified and cloned into pJIT60. For pARF13>>NLS-tdtomato and pBSK2>>NLS-tdtomato, the corresponding promoter fragments (1.97 kb for ARF13 and 2.83 kb for BSK2) were PCR-amplified and replaced the NTA promoter in pNTA>>NLS-tdtomato (46).

For chimeric SSP/BSK1 T-DNA constructs, chimeras were based on two pCambia T-DNAs containing an ∼11-kb fragment spanning the entire SSP locus, with a YFP moiety added in-frame into low-complexity regions of the SSP protein behind the myristoylation motif (after Gly29) or behind the kinase domain (after Ser314) (12). Restriction sites introduced with the YFP moiety were used to exchange segments of the BSK1 genomic sequence encoding for the kinase domain (Gly43-Pro354; “B1KD”) or the TPR domain (after Pro-357, “SKD”) with the corresponding segments of SSP; the YFP moiety was deleted in the process to minimize the number of structural changes. Synthetic fragments (purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies) were used for generating T-DNAs harboring an SSP activation loop embedded in a BSK1 kinase domain (“B1SAL”: SSP Glu196-Ser206 inserted between BSK1 Lys221 and Val246), a BSK1 activation loop embedded in an SSP kinase domain (“SB1AL”: BSK1 Asn222-Arg245 inserted between SSP Lys195 and Val207), and each of the four units of the BSK1 TPR domain embedded in an SSP TPR domain (“B1T0”: linker region and first cryptic repeat, BSK1 Pro357-Met400 inserted between SSP Ser314 and Lys316; “B1T1”: first repeat, BSK1 Lys401-Pro417 substituting for SSP Lys316-Pro398; “B1T2”: second repeat, BSK1 Pro417-Pro452 substituting for SSP Pro398-Pro412; and “B1T3”: BSK1 Pro452-end substituting for SSP Pro412-end).

A normal form of SSP (“SSP”) and an inactive form, in which the Gly2 position carrying the myristoylate modification changed to Ala (“G2A”), served as controls. The “BSK1” T-DNA was created by inserting the BSK1 coding sequence derived from a cDNA clone between the SSP start and stop codons of the normal form of SSP T-DNA.

Transient Expression in Protoplasts.

Dark-grown suspension cell cultures derived from A. thaliana Col-0 were grown and transfected as described previously (47). For qRT-PCR analysis, total RNA was extracted as described below.

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR Analysis.

For expression analysis in plants as well as protoplasts, total RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA samples were treated with DNaseI (Fermentas) to remove any residual genomic DNA. RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas) using oligo(dT) primers.

To detect transcripts and transcript fragments in insertion lines, gene-specific primer pairs upstream, downstream, and flanking the insertion site were used (SI Appendix, Table S1). For measurements of transcript levels, qRT-PCR was carried out on a CFX Connect Thermocycler (Bio-Rad) with SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The PCR was performed with gene-specific primer pairs (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Western Blot.

For Western blot analysis, protoplasts were pelleted in 240 mM CaCl2⋅H2O for 2 min at 3,700 × g. After addition of lysis buffer [25 mM Tris phosphate (pH 7.8), 2 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100], total protein was extracted by repeated manual grinding of frozen samples using liquid nitrogen, and standard Laemmli buffer was added to a final 1× concentration followed by heating at 95 °C for 3 min.

Proteins were separated by size by SDS/PAGE and detected by Western blotting as described previously (48). Phosphorylated MPK6 protein was detected with a Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (D13.14.4E) XP monoclonal antibody (1:2,000 dilution, no. 4370; Cell Signaling Technology). Overall amount of MPK6 was detected with a polyclonal anti-AtMPK6 antibody (1:2,000 dilution, no. A7104; Sigma–Aldrich). Tubulin abundance was used as a loading control and was detected with a monoclonal antitubulin antibody (1:2,000 dilution; Sigma–Aldrich).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay.

Constructs used for the yeast two-hybrid analysis were cloned into the high-copy vectors pGADT7-Dest and pGBKT7-Dest, respectively (Clontech Matchmaker). Both vectors were previously modified to allow for Gateway cloning. For Gateway cloning, coding regions of genes of interests were PCR-amplified with primers containing attB sites (SI Appendix, Table S1). Plasmids were cotransformed into the two-hybrid strain PJ69-4A via lithium acetate transformation (49). Diploid yeasts were dropped in 10-fold serial dilutions on vector-selective [complete supplement medium (CSM) L- W-] and interaction-selective (CSM L- W- H- Ade-) media and grown at 30 °C for 3 d.

rBiFC.

Constructs were cloned into the binary 2in1 vector pBiFCt-2in1-NN (50) and transformed in Agrobacterium strain GV3101. Fluorescence intensities for YFP and RFP were measured from Nicotiana benthamiana leaves 2 d after infiltration using a Leica SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope at 514-nm and 561-nm excitation wavelengths, respectively. YFP/RFP ratios were calculated from 25 different leaf regions and plotted using BoxPlotR (51).

Protein Expression and Purification.

Codon-optimized coding sequences of BSK1, SSP, and YDA kinases encompassing residues 1–292, 1–331, and 1–883, respectively, were cloned into a modified pET vector containing an N-terminal His6-SUMO solubility tag that is removable by tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease-mediated cleavage. OverExpress C41 cells (Lucigen) were transformed with the respective plasmids and grown in LB medium in the presence of kanamycin. Cells were grown at 37 °C to optical densities (OD600) of 0.6, induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and incubated overnight at a temperature of 22 °C. Twelve hours after induction, cells were harvested and stored at −20 °C. Subsequently, pellets were lysed by sonication in lysis buffer supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 100 μg/mL lysozyme. Buffer conditions were 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 10 mM imidazole for BSK1 kinase; 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole for SSP kinase; and 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM imidazole, and 20% (wt/vol) glycerol for YDA. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 30 min to remove insoluble cell debris. The supernatant, supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2, was applied to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin, and the column was washed using 10 column volumes of the respective lysis buffers. The protein was eluted from the resin using lysis buffers supplemented with 200 mM imidazole. YDA protein was left uncleaved, whereas the SUMO tag was removed from BSK1 and SSP kinase constructs by TEV cleavage during dialysis into 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT for SSP kinase and into 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT for BSK1 kinase. The cleaved tag was removed from the target protein using a second Ni-NTA step in dialysis buffer. Finally, a size exclusion chromatography purification step in kinase buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5 mM MgCl2] using a Superdex 200 column yielded pure protein.

Kinase Activity Assay.

Kinase activity was determined using the ADP-Glo Assay (Promega). The experiment was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. In brief, kinase reactions were carried out at 22 °C in kinase buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5 mM MgCl2] in the presence of 100 μM ATP and 1 μM lysozyme as substrates. The kinase concentrations used in this assay were 10 μM for BSK1 and SSP kinase domains and 1 μM for YDA. The reactions were terminated by flash-freezing aliquots in liquid nitrogen at 0, 30, and 60 min. Subsequently, ADP generation in the samples was determined according to ADP-Glo instructions using a Tecan Infinite F200 plate reader.

Microscopic Analysis of Embryos, Measurements, and Reporter Gene Analysis.

Immature seeds were dissected and cleared in Hoyer’s solution as described previously (12). Images were taken with a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z1 microscope equipped with an AxioCam HRc camera. Size measurements were performed using measurement tools of ImageJ (NIH) software (52). Box plot analysis was performed with BoxPlotR (51).

Higher order mutants that are homozygous for bsk1 and bsk2 (bsk1 bsk2; bsk1 bsk2 ssp; and bsk1 bsk2 ssp yda-CA) show reduced fertility due to early defects in embryo sac development. In these cases, only fertilized seeds were taken into account for measurements.

Confocal scanning microscopy was performed with Zeiss LSM780NLO and Leica SP8 confocal microscopes as described previously (53). For staining of cell outlines, SCRI Renaissance blue SR2200 was used according to published protocols (54, 55).

Phenotypic Analysis of Seedlings and Plants.

Images of inflorescences and rosette leaves were taken with a Pentax K-30 digital camera equipped with a 50-mm SMC-M macro lens mounted on a tripod. The area covered by the rosette leaves was determined in images by marking the perimeter of the plant and calculating the selected area using ImageJ software.

For inflorescence images, black neoprene was used as background. Pedicel length of fully open flowers was determined for five independent plants and two flowers each using a caliper.

Epidermal peels (56) were imaged with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope after staining with SR2200 as described previously (54). For propidium iodide (PI) staining, whole cotyledons were submerged in 10 μg/mL PI solution (Sigma–Aldrich) for 15 min. The samples were rinsed twice with water before mounting in water for confocal microscopy. Confocal images of epidermal surfaces were taken with a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope equipped with an HC PL APO 20×/0.75 Imm CORR CS2 objective using a 552-nm diode laser line for excitation. Images were acquired as z-stacks and displayed as maximum projections using ImageJ (52). Stomata index was calculated as the number of stomata per unit area divided by the total number of epidermis cells per unit area multiplied by 100 as described previously (57).

Statistical Analysis of Quantitative Data.

The Student’s t test and Mann–Whitney U test were used for statistical analysis if the data showed a normal distribution or deviated from a normal distribution, respectively.

Phylogenetic Analysis.

The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method based on the Jones, Taylor, Thornton (JTT) matrix-based model (58). Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained by applying the neighbor-joining method to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model. A discrete gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [five categories (+G, parameter = 1.6251)]. The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated; that is, fewer than 5% alignment gaps, missing data, and ambiguous bases were allowed at any position. There were 293 positions in total in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6 (59).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre for providing T-DNA insertion lines; Sebastian Vorbrugg, Anja Pohl, and Martin Vogt for technical assistance; Sangho Jeong for sharing material; Caterina Brancato for protoplast transfections; and Gerd Jürgens for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. Research in our groups is supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) (DFG SFB1101/B01 to M.B. and Emmy Noether Fellowship GR4251/1-1 to C.G.), the National Science Foundation (Award 1257805 to W.L.), and the Max Planck Society.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.W. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1815866116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lau S, Slane D, Herud O, Kong J, Jürgens G. Early embryogenesis in flowering plants: Setting up the basic body pattern. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:483–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawashima T, Goldberg RB. The suspensor: Not just suspending the embryo. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer M, Slane D, Jürgens G. Early plant embryogenesis-dark ages or dark matter? Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;35:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maheshwari P. An Introduction to the Embryology of the Angiosperms. McGraw–Hill; New York: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musielak TJ, Bayer M. YODA signalling in the early Arabidopsis embryo. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:408–412. doi: 10.1042/BST20130230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukowitz W, Roeder A, Parmenter D, Somerville C. A MAPKK kinase gene regulates extra-embryonic cell fate in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2004;116:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Ngwenyama N, Liu Y, Walker JC, Zhang S. Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang M, et al. Maternal control of embryogenesis by MPK6 and its upstream MKK4/MKK5 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2017;92:1005–1019. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmann DC, Lukowitz W, Somerville CR. Stomatal development and pattern controlled by a MAPKK kinase. Science. 2004;304:1494–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1096014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng X, et al. A MAPK cascade downstream of ERECTA receptor-like protein kinase regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture by promoting localized cell proliferation. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4948–4960. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng X, et al. Differential function of Arabidopsis SERK family receptor-like kinases in stomatal patterning. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2361–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayer M, et al. Paternal control of embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2009;323:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1167784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi H, Yan H, Li J, Tang D. BSK1, a receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase, involved in both BR signaling and innate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2013;8:e24996. doi: 10.4161/psb.24996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi H, et al. BR-SIGNALING KINASE1 physically associates with FLAGELLIN SENSING2 and regulates plant innate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1143–1157. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.107904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li ZY, et al. A mutation in Arabidopsis BSK5 encoding a brassinosteroid-signaling kinase protein affects responses to salinity and abscisic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;426:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim TW, Wang ZY. Brassinosteroid signal transduction from receptor kinases to transcription factors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:681–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grütter C, Sreeramulu S, Sessa G, Rauh D. Structural characterization of the RLCK family member BSK8: A pseudokinase with an unprecedented architecture. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:4455–4467. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sreeramulu S, et al. BSKs are partially redundant positive regulators of brassinosteroid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;74:905–919. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu SL, Adams KL. Dramatic change in function and expression pattern of a gene duplicated by polyploidy created a paternal effect gene in the Brassicaceae. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:2817–2828. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slane D, et al. Cell type-specific transcriptome analysis in the early Arabidopsis thaliana embryo. Development. 2014;141:4831–4840. doi: 10.1242/dev.116459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nodine MD, Bartel DP. Maternal and paternal genomes contribute equally to the transcriptome of early plant embryos. Nature. 2012;482:94–97. doi: 10.1038/nature10756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmid M, et al. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat Genet. 2005;37:501–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torii KU, et al. The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell. 1996;8:735–746. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shpak ED, McAbee JM, Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Stomatal patterning and differentiation by synergistic interactions of receptor kinases. Science. 2005;309:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1109710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shpak ED. Diverse roles of ERECTA family genes in plant development. J Integr Plant Biol. 2013;55:1238–1250. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan GL, Li HJ, Yang WC. The integration of Gβ and MAPK signaling cascade in zygote development. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8732. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang W, et al. BSKs mediate signal transduction from the receptor kinase BRI1 in Arabidopsis. Science. 2008;321:557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1156973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt L, Gray JE. The signaling peptide EPF2 controls asymmetric cell divisions during stomatal development. Curr Biol. 2009;19:864–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horst RJ, et al. Molecular framework of a regulatory circuit initiating two-dimensional spatial patterning of stomatal lineage. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B, et al. OsBRI1 activates BR signaling by preventing binding between the TPR and kinase domains of OsBSK3 via phosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:1149–1161. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xing S, Wallmeroth N, Berendzen KW, Grefen C. Techniques for the analysis of protein-protein interactions in vivo. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:727–758. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan H, et al. BRASSINOSTEROID-SIGNALING KINASE1 phosphorylates MAPKKK5 to regulate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:2991–3002. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flannery S, Bowie AG. The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases: Critical regulators of innate immune signalling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1981–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssens S, Beyaert R. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol Cell. 2003;11:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendrola JM, Shi F, Park JH, Lemmon MA. Receptor tyrosine kinases with intracellular pseudokinase domains. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1029–1036. doi: 10.1042/BST20130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, et al. OsBSK1-2, an orthologous of AtBSK1, is involved in rice immunity. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:908. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng X, et al. Ligand-induced receptor-like kinase complex regulates floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis. Cell Reports. 2016;14:1330–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H, et al. SERK family receptor-like kinases function as co-receptors with PXY for plant vascular development. Mol Plant. 2016;9:1406–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, et al. Two SERK receptor-like kinases interact with EMS1 to control anther cell fate determination. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:326–337. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim TW, Guan S, Burlingame AL, Wang ZY. The CDG1 kinase mediates brassinosteroid signal transduction from BRI1 receptor kinase to BSU1 phosphatase and GSK3-like kinase BIN2. Mol Cell. 2011;43:561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valley CC, et al. Enhanced dimerization drives ligand-independent activity of mutant epidermal growth factor receptor in lung cancer. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:4087–4099. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-05-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinna LA. The raison d’être of constitutively active protein kinases: The lesson of CK2. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:378–384. doi: 10.1021/ar020164f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babu Y, Musielak T, Henschen A, Bayer M. Suspensor length determines developmental progression of the embryo in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1448–1458. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.217166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alonso JM, et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwechheimer C, Smith C, Bevan MW. The activities of acidic and glutamine-rich transcriptional activation domains in plant cells: Design of modular transcription factors for high-level expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:195–204. doi: 10.1023/a:1005990321918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong J, Lau S, Jürgens G. Twin plants from supernumerary egg cells in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2015;25:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schütze K, Harter K, Chaban C. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) to study protein-protein interactions in living plant cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;479:189–202. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-289-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reichardt I, et al. Mechanisms of functional specificity among plasma-membrane syntaxins in Arabidopsis. Traffic. 2011;12:1269–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asseck LY, Wallmeroth N, Grefen C. ER membrane protein interactions using the split-ubiquitin system (SUS) Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1691:191–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7389-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grefen C, Blatt MR. A 2in1 cloning system enables ratiometric bimolecular fluorescence complementation (rBiFC) Biotechniques. 2012;53:311–314. doi: 10.2144/000113941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spitzer M, Wildenhain J, Rappsilber J, Tyers M. BoxPlotR: A web tool for generation of box plots. Nat Methods. 2014;11:121–122. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Musielak TJ, Slane D, Liebig C, Bayer M. A versatile optical clearing protocol for deep tissue imaging of fluorescent proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Musielak TJ, Schenkel L, Kolb M, Henschen A, Bayer M. A simple and versatile cell wall staining protocol to study plant reproduction. Plant Reprod. 2015;28:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s00497-015-0267-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Musielak TJ, Bürgel P, Kolb M, Bayer M. Use of SCRI renaissance 2200 (SR2200) as a versatile dye for imaging of developing embryos, whole ovules, pollen tubes and roots. Bio Protoc. 2016;6:e1935. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eisele JF, Fäßler F, Bürgel PF, Chaban C. A rapid and simple method for microscopy-based stomata analyses. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salisbury EJ. On the causes and ecological significance of stomatal frequency, with special reference to the woodland flora. Philos Trans R Soc B. 1928;216:1–65. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.