Abstract

Objectives:

Apathy is common in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and has far-reaching impact on patients’ clinical course and management needs. However, it is unclear if apathy is an integral component of AD or a manifestation of depression in cognitive decline. This study aims to examine interrelationships between apathy, depression and patients’ function.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

A cross sectional study of well-characterized AD patients in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS) with Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) between 0.5 and 2.

Main Outcomes and Measures:

Participants’ function was measured using the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ). Apathy and depression were measured using clinician judgment and also informant- reported Neuropsychiatric Inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q). Dementia severity was categorized by CDR.

Results:

Sample included 7,679 participants (55.7% men) with a mean(SD) age of 74.9(9.7) years. 3,197 (41.6%) had apathy based on clinician judgment. Among those who had apathy, approximately half had no depression. Presence of apathy was associated with 21%, 10% and 3% worsening in function compared to those without apathy in CDR=0.5, 1, and 2 groups, respectively. Depression was not independently associated with functional status. Results revealed no interaction between apathy and depression.

Conclusions:

Apathy, but not depression, was significantly associated with worse function, with the strongest effects in mild dementia. Results emphasize the need for separate assessments of apathy and depression in the evaluation and treatment of patients with dementia. Understanding their independent effects on function will help identify patients who may benefit from more targeted management strategies.

Keywords: dementia, apathy, depression, functional status, disease severity

INTRODUCTION

Apathy is the most frequent behavioral symptom in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), occurring in about 65% of all patients1–12. It appears early and often persists throughout all stages of the disease and has far- reaching impact on patients’ clinical course and management needs. Apathy is associated with more impairment in activities of daily living (ADL) than patients’ cognitive status would otherwise suggest11,13–17, and also is associated with more rapid cognitive and functional decline, longer illness duration, and increased dementia severity.2,3,17,18 Apathetic patients rely on caregivers to initiate activities that they are otherwise incapable of doing by themselves, have worse quality of life and are more likely to be institutionalized earlier.8,11,13,15,16,19 Caregivers of patients with apathy report significantly higher levels of distress compared to caregivers of patients without apathy.11,20

Although less prevalent than apathy, depression in AD has received more attention in dementia research. Substantial overlap in key symptoms often results in misinterpretation of apathy as depression.2,3,8,14,16,21–26 However, nearly half of AD patients with apathy have no concomitant depression. Growing evidence of distinct pathophysiology and differences in appropriate pharmacological and psychosocial interventions has led to the conclusion that apathy and depression have divergent natural histories, and that apathy is a separate and distinct syndrome from depression.2,8,11,12,14,16,23,24,27

Functional disability is unsafe for patients with dementia’ anxiety provoking and burdensome for families and caregivers. A large portion of costs of care for patients with dementia can be attributed to functional disability.28 While it might be presumed that cognitive decline or memory deficits drive functional decline’ several studies have identified apathy and depression as important contributors to functional decline in AD patients.9,11,14,15,17,29 These studies have been limited by relatively small sample sizes or use of convenient clinical samples. The inter-relationships between apathy’ depression and function across dementia severity have not been examined.

In this study’ we aim to examine (1) when and how often does apathy appear in AD’ (2) if apathy impinges upon functional status independent of cognitive status’ and (3) if apathy can be distinguished from depression. Data used in this study were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC UDS)’ providing the largest sample of AD patients with standardized assessments of apathy to be reported. As treatment of apathy and depression differ’ understanding their independent effects on function will help identify patients who may benefit from more targeted management strategies.

METHODS

Data Source and Sample Derivation

Data are drawn from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS)30. Recruitment’ participant evaluation’ and diagnostic criteria are detailed elsewhere31. Briefly’ beginning in September 2005’ participants have been followed prospectively from 33 National Institute of Aging funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs). Recruitment is ongoing. All ADCs enroll and follow participants with a standardized protocol and provide data for research through NACC. Participants were followed at approximately 12 month intervals using standard evaluations and reassessment at each visit. Informed consent was provided by all participants and their informants. The NACC-UDS provides systematic information on demographics, behavioral status, cognitive testing, medical history, family history, clinical impressions, and diagnoses using standardized forms. However, because each ADC enrolls participants with its own inclusion criteria, NACC sample should not be considered a population based sample. Data used in the current study are comprised of participants who were enrolled in NACC up to May 2015 who had a clinical diagnosis of AD as determined by clinician consensus at the initial visit.

Measures

Function.

Our main dependent variable is participants’ function, measured using the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ) reported from interviews with study partners.32 The FAQ is often used in clinical settings to assess functional deficit for the elderly and shows good sensitivity, specificity and inter-rater reliability. The FAQ asks whether the participant had any difficulty or need help with 10 items in the previous 4 weeks on a scale from 0–3, corresponding to normal (0), has difficulty but does by oneself (1), required assistance (2), and dependent (3). Responses to each item are summed to obtain a total FAQ score (range=0–30). Higher scores indicate worse function. Individual items could be missing depending on whether the informant reported that the participant attempted the task in the past 4 weeks. To adjust for these missing values, we divided the total FAQ score by the number of tasks attempted to obtain a standardized score (range 0 to 3).33 Individuals who were reported to have not attempted any tasks and had a missing value for all FAQ items were excluded from the analysis. Constructed as such, the standardized FAQ score can be considered an average rating of participant’s difficulty across all items.

Apathy and Depression.

One of the most frequently used scales to assess apathy and depression in the literature is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q), a retrospective (up to 1 month) informant based rating scale for psychopathology in patients with dementia.34,35 In the NPI-Q, the informant reported presence of apathy (apathy or indifference in the last month) and depression (depression or dysphoria in the last month). If presence of a symptom is reported, then severity (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe) is subsequently rated. The content validity, concurrent validity, inter-rater reliability and test-retest reliability of the NPI-Q have been established.34,36

As often as the NPI-Q is used,36 it is not a gold standard to assess apathy. Existing studies suggest that it should not be used as the sole measure for assessing apathy.10 In the current study, presence of apathy and depression also is determined by clinician judgment within the NACC assessment protocol, based on all available information including clinical measurement, informant report, and medical records review, and indicates whether the participant currently manifests meaningful change in behavior in apathy (yes=1, no=0), and depressed mood (yes=1, no=0).

Demographics and other Clinical Characteristics.

Dementia severity was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) which has the advantage of being well standardized and segmenting dementia into well- understood levels of severity.37 Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race (non-Hispanic white, non- Hispanic black, vs. other), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino vs. other), and years of education. Participant medical history was self-reported and included history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, urinary incontinence, thyroid disease, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, alcohol abuse, current smoking, congestive heart failure, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, sleep apnea.

Statistical Analysis

Relationship between apathy and depression and the standardized FAQ were estimated using linear regression models. Separate models were estimated using clinician judgment and informant-reported NPI-Q. For the model using clinician judgment, the main independent variables include presence of apathy, presence of depression, and an interaction term between depression and apathy. For the model using NPI-Q, the main independent variables included fully interacted terms between depression (0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe) and apathy (0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe). Control variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, years of education, an indicator for any APOE e4 allele, an indicator for missing APOE information, and indicators for conditions reported by >5% of the participants. These conditions included history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, urinary incontinence, thyroid disease, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, alcohol abuse, and current smoking. Indicators for each ADC site at which the participant was recruited were included to control for possible differences in site specific variations in data collection and measurements.

Association between apathy, depression and individual FAQ items were estimated using ordered logit regression. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) greater than 1 indicates that the independent variable is positively associated with worse functioning in the specific item.

All analyses were conducted by dementia severity to estimate. Analyses were performed using Stata 13.0. Statistical significance was set a priori at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample consists of 8,829 participants who had a clinical diagnosis of AD as determined by clinician consensus at the initial visit. Of these, 738 participants with CDR=3 were excluded because they had disproportional amount of missing data. For example, 27.8% of participants with CDR=3 were not administered the MMSE (compared to 1%, 1.7%, 5% in those with CDR=0.5, 1, and 2), and 11.3% have missing values in NPI-Q (compared to 1.9%, 3.2%, 3.7% in those with CDR=0.5, 1, and 2). 5 participants with CDR=0 were also excluded. The analytic sample therefore includes 7,679 participants who were diagnosed with AD with CDR of 0.5, 1, and 2 at their initial visits.

Of these 7,679 participants, 3,197 (41.6%) had apathy based on clinician judgment and 4,482 (58.4%) did not (Table 1). Prevalence of apathy is higher in those with more severe dementia, ranging from 27.8% in those with CDR=0.5, 44.5% in CDR=1, to 58.8% in CDR=2 (χ2=369.971, df=2, p<0.001). Most common conditions included hypertension (49.7%), hypercholesterolemia (48.3%), urinary incontinence (16.5%), thyroid disease (14.2%), and diabetes (12.4%). χ2 test showed that rates of urinary incontinence in participants with apathy (17.8%) was higher than those without apathy (15.5%, χ2=7.041, df=1, p=0.008). Similarly, rate of diabetes in participants with apathy (13.7%) was higher than those without apathy (11.4%, χ2=8.566, df=1, p=0.003). Participants with apathy had worse scores in all clinical measures than those without apathy. Specifically, compared to those without apathy, participants with apathy had substantially worse scores in the overall standardized FAQ (1.8(0.3) vs. 1.4(0.8), t=−21.416, df=7677, p<0.001), MMSE (19.8(5.7) vs. 21.0(5.4), t=9.172, df=7677, p<0.001), NPI-Q (6.3(4.9) vs. 3.9(4.2), t=−23.430, df=7535, p<0.001), and GDS (2.9(2.8) vs. 2.3(2.4), t=- 8.653, df=7203, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by clinician judgment of presence of apathy across dementia severity groups.

| All Sample | CDR:=0.5 | CDR=1 | CDR=2 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No apathy |

With apathy |

p- value |

No apathy |

With apathy |

No apathy |

With apathy |

No apathy |

With apathy |

||||||||

| n (%) | 4,482 | (58.4) | 3,197 | (41.6) | 1,781 | (72.2%) | 687 | (27.8%) | 2,147 | (55.5) | 1,718 | (44.5) | 554 | (41.2) | 792 | (58.8) | |

| Age, mean(sd) | 75.3 | (9.6) | 74.5 | (9.8) | <0.001 | 74.0 | (9.3) | 73.1 | (9.1) | 75.5 | (9.7) | 74.6 | (9.9) | 78.4 | (9.7) | 75.5 | (10.1) |

| Male, n (%) | 1,851 | (41.3) | 1,549 | (48.5) | <0.001 | 794 | (44.6) | 371 | (54.0) | 884 | (41.2) | 839 | (48.8) | 173 | (31.2) | 339 | (42.8) |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| White | 3,574 | (79.7) | 2,548 | (79.7) | 1,473 | (82.7) | 575 | (83.7) | 1,714 | (79.8) | 1,374 | (80.0) | 387 | (69.9) | 599 | (75.6) | |

| Black | 591 | (13.2) | 345 | (10.8) | 198 | (11.1) | 60 | (8.7) | 285 | (13.3) | 178 | (10.4) | 108 | (19.5) | 107 | (13.5) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 352 | (7.9) | 327 | (10.2) | <0.001 | 88 | (4.9) | 43 | (6.3) | 191 | (8.9) | 162 | (9.4) | 73 | (13.2) | 122 | (15.4) |

|

Education, mean(sd) |

14.1 | (3.7) | 14.1 | (3.9) | 0.393 | 14.5 | (3.4) | 14.7 | (3.5) | 14.0 | (3.8) | 14.2 | (3.7) | 12.8 | (4.2) | 13.3 | (4.3) |

|

Any APOE e4 n (%) |

1,940 | (43.3) | 1,374 | (43.0) | 0.789 | 830 | (46.6) | 312 | (45.4) | 899 | (41.9) | 732 | (42.6) | 211 | (38.1) | 330 | (41.7) |

|

Comorbidities, n (%) |

|||||||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 2,253 | (50.4) | 1,563 | (49.1) | 0.254 | 851 | (47.9) | 324 | (47.4) | 1,116 | (52.1) | 828 | (48.4) | 286 | (51.7) | 411 | (52.0) |

|

Hypercholestero lemia |

2,105 | (47.5) | 1,561 | (49.3) | 8 | 898 | (50.9) | 350 | (51.3) | 982 | (46.3) | 851 | (50.1) | 225 | (41.2) | 360 | (46.0) |

| Urinary incontinence |

694 | (15.5) | 567 | (17.8) | 0.008 | 209 | (11.8) | 319 | (11.1) | 319 | (14.9) | 260 | (15.2) | 166 | (30.1) | 231 | (29.2) |

| Thyroid disease |

641 | (14.4) | 439 | (13.8) | 0.513 | 230 | (13.0) | 101 | (14.9) | 313 | (14.7) | 212 | (12.4) | 98 | (17.8) | 126 | (16.0) |

| Diabetes | 512 | (11.4) | 436 | (13.7) | 0.003 | 198 | (11.1) | 80 | (11.7) | 244 | (11.4) | 227 | (13.3) | 70 | (12.7) | 129 | (16.3) |

|

Clinician judgment |

<0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

|

of depression, n(%) |

1,241 | (27.7) | 1,552 | (48.5) | 452 | (25.4) | 339 | (49.3) | 633 | (29.5) | 828 | (48.2) | 156 | (28.2) | 385 | (48.6) | |

| FAQ, mean(sd) | 13.4 | (8.1) | 17.2 | (7.9) | <0.001 | 7.8 | (5.5) | 9.5 | (5.7) | 15.4 | (6.7) | 16.9 | (6.4) | 24.0 | (5.6) | 24.5 | (5.3) |

|

Standardized FAQ, mean(sd) |

1.4 | (0.8) | 1.8 | (0.8) | <0.001 | 0.8 | (0.6) | 1.0 | (0.6) | 1.6 | (0.7) | 2.5 | (0.6) | 2.5 | (0.5) | 2.6 | (0.5) |

| NPI-Q, mean(sd) | 3.8 | (4.2) | 6.3 | (4.9) | <01 | 3.0 | (3.3) | 4.9 | (4.1) | 4.1 | (4.3) | 6.2 | (4.7) | 5.9 | (5.4) | 7.6 | (5.4) |

| GDS, mean(sd) | 2.3 | (2.4) | 2.9 | (2.8) | <0.001 | 2.4 | (2.5) | 2.9 | (2.8) | 2.3 | (2.4) | 2.9 | (2.8) | 2.3 | (2.6) | 2.8 | (2.9) |

| MMSE,mean(sd) | 21.0 | (5.4) | 19.8 | (5.7) | <0.001 | 24.0 | (3.5) | 24.2 | (3.4) | 20.5 | (4.7) | 20.6 | (4.5) | 13.7 | (5.5) | 14.4 | (5.5) |

Notes: Between group differences were compared using χ2 test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test χ2 (df=2) for continuous variables.

Abbreviations: standard FAQ, functional activities questionnaire (range=0–3); MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination (range=0–30); NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory questionnaire (range=0–36); GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale (range=0–15).

Comparison of Clinician Judgment of Apathy and Informant assessment

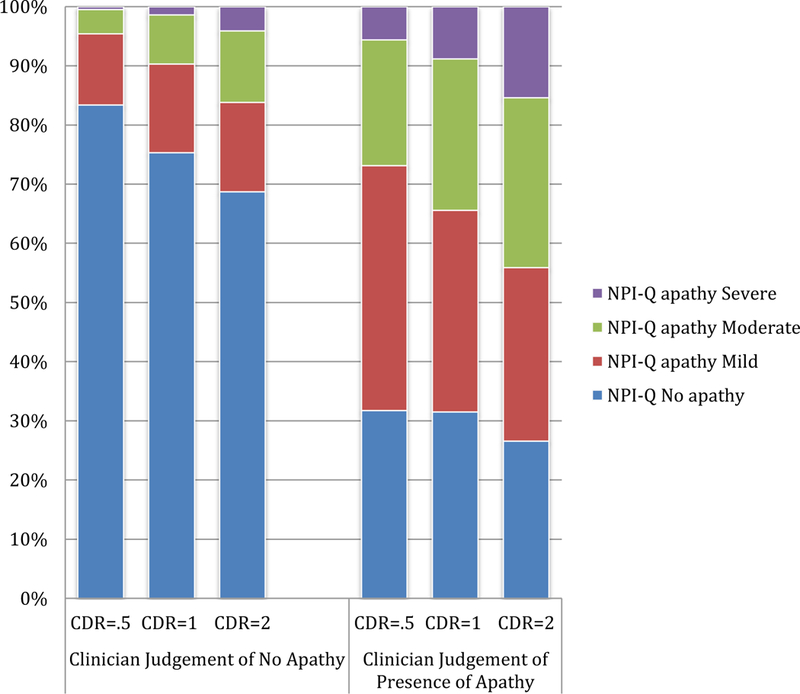

Clinician judgment of presence of apathy was correlated with informant assessment of apathy but with disagreements. Among individuals with a clinician judgment of apathy, 69.7% were rated by their informant in the NPI-Q as having apathy, ranging from 68% for those with CDR=0.5 or 1 to 73.4% for those with CDR=2 (Figure 1). Conversely, among individuals who were without apathy by clinician judgment, 77.8% also were rated by their informant as without apathy, ranging from 83.4% for those with CDR=0.5, 75.4% for those with CDR=1, to 68.5% for those with CDR=2.

Figure 1.

Comparison between informant-reported apathy (NPI-Q) and clinician judgment of presence of apathy, by CDR

Estimated Effects of Clinician Judgment of Apathy on Function

Multivariate analyses revealed that apathy was significantly associated with worse FAQ scores for all CDR groups (Table 2). Specifically, presence of apathy was associated with a 0.180(0.033) point increase in the standardized FAQ for those with CDR=0.5 (95% CI=[0.114, 0.245], t=5.41, p<0.001), a 0.176(0.027) point increase for those with CDR=1 (95% CI=[0.114, 0.245], t=5.41, p<0.001), and a 0.062(0.032) point increase for those with CDR=2 (95% CI=[0.001, 0.125], t=1.97, p=0.049). Putting these estimates into context with the mean(SD) FAQ scores of 0.892(0.586), 1.718(0.656), and 2.541(0.456) for CDR=0.5, 1, and 2 groups implies that apathy was associated with a 21%, 10% and 3% increase in the FAQ compared to those without apathy in each group. On the contrary, association between depression and function was statistically insignificant in all CDR groups. Specifically, presence of depression was associated with a 0.003(0.039) point increase in the standardized FAQ for CDR=0.5 (95% CI=[−0.073, 0.079], t=0.07, p=0.940), a 0.024(0.038) point decrease for CDR=1 (95% CI=[−0.091, 0.049], t=−0.63, p=0.526), and a 0.032(0.049) point increase for CDR=2 (95% CI=[−0.064, 0.297], t=0.65, p=0.513). The interaction term between apathy and depression also were statistically insignificant for all CDR groups.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analysis Examining Relationship between Clinician Judgment of Apathy, Depression and Function, by CDR.

| Interaction effects models | Main effects models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables |

CDR=0.5 B (95% CI) |

CDR=1 B (95% CI) |

CDR=2 B (95% CI) |

CDR=0.5 B (95% CI) |

CDR=1 B (95% CI) |

CDR=2 B (95% CI) |

| Apathy | 0.185*** | 0.176*** | 0.062* | 0.194*** | 0.18*** | 0.041* |

| (0.114, 0.245) | (0.124, 0.228) | (0.001, 0.125) | (0.143, 0.244) | (0.139, 0.221) | (0.011, 0.092) | |

| Depression | 0.003 | −0.024 | 0.032 | 0.015 | −0.019 | −0.006 |

| (−0.073, 0.079) | (−0.098, 0.050) | (−0.065, 0.130) | (−0.053, 0.083) | (−0.081, 0.044) (−0.078, 0.066) | ||

|

Apathy x depression |

0.035 | 0.011 | −0.06 | - | - | - |

| (−0.066, 0.136) | (−0.071, 0.093) | (−0.164, 0.043) | ||||

|

Standardized FAQ, mean(sd) |

0.892 (0.586) | 1.718 (0.656) | 2.541 (0.456) | 0.892 (0.586) | 1.718 (0.656) | 2.541 (0.456) |

Notes: Multiple linear regression analysis to examine the relationship between patients’ function and clinical judgement of apathy and depression. All models controlled for age, male, white, black, Hispanic, education, any apoe 4 genotype, indicator for missing apoe values, indicators for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, urinary incontinence, thyroid disease, diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, and indicators for ADC sites (detailed estimates available from authors). b, regression coefficient estimate; CI, confidence interval;

two-sided p <.05,

two-sided p<0.001

Main effects models without the interaction term between apathy and depression showed substantively similar results of strong associations between apathy and function. Chow test for differences in regression coefficients by CDR groups showed that the magnitudes of the effects were significantly larger in milder CDR groups (CDR=0.5 vs. CDR=1, F(3, 7807)=96.12, p<0.001; CDR=1 vs. CDR=2, F(3,5289)=59.23, p<0.001).38

Estimated Effects of Informant Assessment of Apathy on Function

Multivariate analyses including the interaction terms between informant assessed apathy and depression revealed that as a group, the interactions were statistically insignificant for all CDR groups (CDR=0.5, F(9,2365)=1.42, p=0.172; CDR=1, F(9,3647)=1.77, p=0.07; CDR=2, F(9,1246)=0.78, p=0.64) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Analysis Examining Relationship between NPI-Q measures of Apathy, Depression and Function, by CDR.

| Independent variables | Interaction effects models | Main effects models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR=0.5 | CDR=1 | CDR=2 | CDR=0.5 | CDR=1 | CDR=2 | |

| b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | |

| Apathy (reference=none) | ||||||

| Mild | 0.111*** | 0.135*** | 0.052 | 0.140*** | 0.085*** | 0.042 |

| (0.038,0.183) | (0.068,0.202) | (−0.027,0.130) | (0.085,0.195) | (0.035,0.135) | (−0.020,0.103) | |

| Moderate | 0.311*** | 0.215*** | 0.125*** | 0.320*** | 0.192*** | 0.130*** |

| (−0.188,0.433) | (−0.132,0.298) | (−0.040,0.211) | (−0.240,0.400) | (−0.133,0.250) | (0.066,0.195) | |

| Severe | 0.346* | 0.347*** | 0.125** | 0.279*** | 0.360*** | 0.125** |

| (−0.011,0.703) | (0.181,0.513) | (0.006,0.243) | (0.110,0.448) | (0.260,0.460) | (0.039,0.210) | |

| Depression (reference=none) | ||||||

| Mild | 0.05 | 0.044 | −0.001 | 0.075** | 0.018 | 0.004 |

| (−0.017,0.117) | (−0.022,0.111) | (−0.093,0.092) | (0.019,0.130) | (−0.033,0.068) | (−0.057,0.065) | |

| Moderate | 0.028 | 0.063 | 0.067 | 0.052 | 0.032 | 0.024 |

| (−0.071,0.128) | (−0.037,0.162) | (−0.061,0.195) | (−0.023,0.128) | (−0.034,0.098) | (−0.053,0.101) | |

| Severe | 0.517** | 0.194 | −0.241 | 0.176 | −0.019 | −0.075 |

| (−0.193,0.842) | (−0.023,0.410) | (−0.596,0.114) | (−0.007,0.358) | (−0.148,0.110) | (−0.213,0.064) | |

| Interaction w/ Mild Apathy | ||||||

| Mild Depression | 0.103 | −0.116** | −0.003 | |||

| (−0.023,0.228) | (−0.226,−0.005) | (−0.143,0.137) | ||||

| Moderate Depression | 0.014 | −0.065 | −0.058 | |||

| (−0.160,0.187) | (−0.223,0.094) | (−0.263,0.148) | ||||

| Severe Depression | −0.286 | −0.308 | −0.18 | |||

| (−0.833,0.261) | (−0.698,0.082) | (−0.741,0.382) | ||||

| Interaction w/ ModerateApathy | ||||||

| Mild Depression | −0.001 | −0.009 | 0.006 | |||

| (−0.196,0.194) | (−0.146,0.128) | (−0.148,0.161) | ||||

| Moderate Depression | 0.069 | −0.093 | −0.014 | |||

| (−0.133,0.270) | (−0.248,0.062) | (−0.196,0.167) | ||||

| Severe Depression | −0.378 | −0.196 | 0.175 | |||

| (− | (− | (− | ||||

| 0.861,0.105) | 0.520,0.128) | 0.245,0.594) | ||||

| Interaction w/ Severe Apathy | ||||||

| Mild Depression | 0.033 | 0.119 | 0.062 | |||

| (−0.533,0.599) | (−0.156,0.393) | (−0.191,0.315) | ||||

| Moderate Depression | 0.095 | 0.07 | −0.122 | |||

| (−0.349,0.539) | (−0.180,0.320) | (−0.335,0.092) | ||||

| Severe Depression | −0.672 | −0.407 | 0.279 | |||

| (−1.232,−0.112) | (−0.753,−0.060) | (−0.135,0.693) | ||||

Notes: Multiple linear regression analysis to examine the relationship between patients’ function and clinical judgement of apathy and depression. All models controlled for age, male, white, black, Hispanic, education, any apoe 4 genotype, indicator for missing apoe values, indicators for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, urinary incontinence, thyroid disease, diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, and indicators for ADC sites (detailed estimates available from authors). b, regression coefficient estimate; CI, confidence interval.

two-sided p<.05,

two-sided p<0.01,

two-sided p<0.001.

Main effects models showed that informant assessed depression was associated with worse FAQ scores for individuals with CDR=0.5 (F(3,2374)=3.16, p=0.02), but associations were statistically insignificant for CDR=1 (F(3,3656)=0.46, p=0.71) and CDR=2 (F(3,1225)=0.64, p=0.59) groups. Associations between apathy and FAQ are much stronger. compared to individuals without apathy, those rated by their informant as having mild, moderate, or severe apathy were associated with worse FAQ scores in all CDR groups (CDR=0.5, F(3, 2374)=26.35; CDR=1, F(3, 3656)=25.67; CDR=2, F(3, 1255)=6.35, all p<0.001). Within each CDR group, the magnitudes of the effect of apathy were larger for those rated with moderate apathy than those with mild apathy (CDR=0.5, estimated coefficient(SE)=0.320(0.040) vs. 0.140(0.028), F(1, 2374)=16.19, p<0.001; CDR=1, estimated coefficient(SE)=0.192(0.030) vs. 0.085(0.025), F(1, 3656)=10.37, p=0.0013; CDR=2, estimated coefficient(SE)=0.130(0.033) vs. 0.042(0.031), F(1, 1255)=6.06, p=0.014). Effects of severe apathy was larger than moderate apathy in all CDR groups but significant only in CDR=1 (estimated coefficient (SE)=0.369(0.051) vs. 0.192(0.030), F(1, 3656)=9.74, p=0.002).

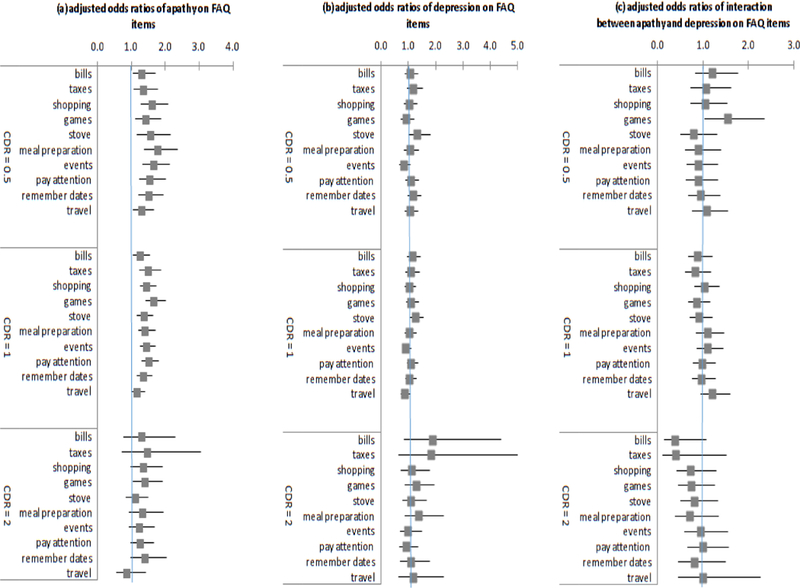

Estimated Effects of Apathy on Individual FAQ Items

Figure 2 summarized ordered logit regression estimates of the effects of (a) apathy, (b) depression, and (c) their interaction on individual FAQ items, separately estimated by CDR groups. Results in panel (a) showed apathy was significantly associated with higher likelihood of being in a worse functional category for all FAQ items for individuals with CDR=0.5 and CDR=1. In the CDR=0.5 group, AOR(SE) ranged from 1.327(0.148) for having difficulty/need help with travelling out of the neighborhood, driving, or arranging to take public transportation (95% CI=[1.066, 1.652], z=2.53, p=0.011) to 1.801(0.241) for having difficulty/need help with meal preparation (95% CI=[1.386, 2.342], z=4.40, p<0.001). In the CDR=1 group, AOR ranged from 1.187(0 .098 for travel (95% CI=[1.009, 1.397], z=2.07 p=0.038) to 1.667( 0.142) (95% CI=[1.411, 1.970], z=6.00, p<0.001) for having difficulty/need help with playing a game of skill such as bridge or chess or work on a hobby. In the CDR=2 group, although all AORs of effects of apathy were greater than 1, suggesting apathy was significantly associated with higher likelihood of being in a worse functional category, none of the estimated effects were statistically significant. Results in panel (b) showed that regardless of CDR status, association between depression and FAQ items were consistently statistically insignificant. Results in panel (c) showed that there was no interaction effect between apathy and depression on individual FAQ items for any CDR groups. (Full estimation results are available upon request.)

Figure 2.

Odds ratios from ordered logistic regression estimates of effects of apathy and depression on individual FAQ items by CDR. Notes: Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of (a) apathy, (b) depression, and (c) interaction between apathy and depression on individual FAQ items, by CDR group. Adjusted odds ratios are interpreted as the increased likelihood of being at a more dependent level for FAQ for 1 unit increase in the independent variable. All models controlled for age, male, white, black, Hispanic, education, any apoe 4 genotype, indicator for missing apoe values, indicators for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, urinary incontinence, thyroid disease, diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, and indicators for ADC sites (detailed estimates available from authors).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we first assessed rates of apathy and depression in a large national sample of AD participants. Consistent with earlier results23,24, we found apathy occurs early in the disease, and is common across the AD spectrum as determined by expert clinicians as well as from informant reports, present in over 40% of cases by both measures. Prevalence of apathy is higher in those with more severe dementia, ranging from 27.8% in those with CDR=0.5, 44.5% in CDR=1, to 58.8% in CDR=2.

We confirmed substantial overlap but also differentiation between apathy and depression. Consistent with the categorization of patients into cohorts of “pure apathy”, “pure depression” or “apathy and depression” suggested by Starkstein23,24, we found 20% of our sample having both apathy and depression by clinician judgment, 22% having apathy but not depression, and 16% having depression but not apathy. Nearly half of AD patients who had apathy had no depression. Similar rates were found using informant-reported NPI-Q. There is again substantial overlap but also differentiation between apathy and depression. Nearly half of AD patients with apathy (47%) were reported by their informants as having no depression.

Our results extend the literature to highlight the important differential relationship between apathy, depression and function across dementia severity levels. Results showed that for all disease severity groups, apathy, but not depression, was significantly associated with patients’ function, with the strongest effects in patients with mild dementia. There is no established cut-off score for impairment on the FAQ. However, FAQ score of ≥6 (equivalent to a score of ≥0.6 on the standardized FAQ when responses to all questions are non-missing) has been suggested to indicate functional impairment. Maintaining function is of critical importance in patients with early dementia. Apathy is present in 28% of participants with CDR=0.5 and in 45% of those with CDR=1. Our estimated results that showed presence of apathy associated with 21% and 10% worsening in function in these groups suggest these relationships are clinically meaningful and that early dementia cases may offer the greatest opportunity for intervention.

Independent of apathy, results showed that presence of depression was not significantly associated with patients’ function in any dementia severity group. There also was no interaction on function between apathy and depression in any severity group. These results suggest that the associations between apathy and functional status of AD patients occur outside the context of depression and are independent of depression. Functional impairments previously attributed to depression in AD might be better explained by the presence of apathy. These differential patterns of associations, together with the high prevalence of apathy, emphasize the need to assess apathy separately from depression in the evaluation and treatment of dementia patients.

In this study, we used two different methods to identify apathy and depression. Regardless of which method was used, similarly strong relationships between apathy and function that were independent of depression were observed in all disease severity groups, strengthening the conclusions of this study. The robustness of the results was further supported by results from models estimating individual items in the FAQ.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, although this study included the largest cohort to date of individuals with apathy, it should be noted that it is not representative of the general population. Second, the cross-sectional design of the current study limits inferences to associations, and also precludes assessments of symptom fluctuations over time within individuals. Over the past several decades there have been efforts to standardize the definition of apathy, develop assessment tools, and operationalize diagnostic criteria.7,22,23,39 More recently, a task force of international experts developed a set of new diagnostic criteria for apathy in dementia, defining apathy as primarily characterized by diminished motivation for a minimum four-week period.12 Future studies will assess the implications of using the new diagnostic criteria for apathy in dementia.

In conclusion, apathy appears early in the course of the disease, is highly prevalent across the AD spectrum, and is strongly associated with patients’ functional status, suggesting that apathy should be considered a core symptom of AD. Apathy places additional burden on caregivers already caring for patients with diminished abilities. An improved understanding of factors associated with functional impairment will enable early identification and development of treatment to reduce functional dependence in patients with AD. The magnitude and strengths of the relationship between apathy and patients’ function independent of depression suggest that functional impairments that previously attributed to depression in AD might be better explained by presence of apathy. These results highlight the need for careful differentiation of apathy from depression. Distinguishing apathy and depression will permit better precision in characterizing patients, facilitating investigations into specific treatment that may lead to improvements in the management and care of patients with AD. Because apathy appears early in the course of AD and has the largest effects on function in mild AD, it may represent a useful target for treatment to reduce disability and perhaps reduce costs of care among patients with AD.

HIGHLIGHTS

1). What is the primary question addressed by this study?

Is apathy an integral component of Alzheimer’s disease or a manifestation of depression in cognitive decline?

2). What is the main finding of this study?

Across all dementia severity, apathy, but not depression, was significantly associated with worse functional status, with the strongest effect in patients with mild dementia. Results revealed no interaction between apathy and depression.

3). What is the meaning of the finding?

Apathy is a core symptom of AD, appears early in the course of the disease, and significantly impinges upon patients’ function independent of dementia severity and depression.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NACC UDS (U01 AG016976) and Alzheimer Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai (U01 P50 AG005138). All authors also are supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sponsor’s Role: Sponsor played no role in the design, methods, participant recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, Gornbein J. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. January 1996;46(1):130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME. Prevalence of apathy, dysphoria, and depression in relation to dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. Summer 2005;17(3):342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, Robinson RG. A prospective longitudinal study of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. January 2006;77(1):8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aalten P, Verhey FR, Boziki M, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in dementia. Results from the European Alzheimer Disease Consortium: part I. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(6):457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. September 25 2002;288(12):1475–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and normal cognitive aging: population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. October 2008;65(10):1193–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starkstein SE, Leentjens AF. The nosological position of apathy in clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. October 2008;79(10):1088–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagariello P, Girardi P, Amore M. Depression and apathy in dementia: same syndrome or different constructs? A critical review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. Sep-Oct 2009;49(2):246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle PA, Malloy PF, Salloway S, Cahn-Weiner DA, Cohen R, Cummings JL. Executive dysfunction and apathy predict functional impairment in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Mar-Apr 2003;11(2):214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman C, Liu CS, Herrmann N, Lanctot KL. Prevalence, neurobiology, and treatments for apathy in prodromal dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. February 2018;30(2):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onyike CU, Sheppard JM, Tschanz JT, et al. Epidemiology of apathy in older adults: the Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. May 2007;15(5):365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. March 2009;24(2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle PA, Malloy PF. Treating apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(1–2):91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam LC, Tam CW, Chiu HF, Lui VW. Depression and apathy affect functioning in community active subjects with questionable dementia and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. May 2007;22(5):431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton LE, Malloy PF, Salloway S. The impact of behavioral symptoms on activities of daily living in patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Winter. 2001;9(1):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeager CA, Hyer L. Apathy in dementia: relations with depression, functional competence, and quality of life. Psychol Rep. June 2008;102(3):718–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lechowski L, Benoit M, Chassagne P, et al. Persistent apathy in Alzheimer’s disease as an independent factor of rapid functional decline: the REAL longitudinal cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. April 2009;24(4):341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dalen JW, van Wanrooij LL, Moll van Charante EP, Brayne C, van Gool WA, Richard E. Association of Apathy With Risk of Incident Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. July 18 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Salvador T, Lyketsos CG, Baker A, et al. Quality of life in dementia patients in long-term care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. February 2000;15(2):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, Geldmacher DS. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. December 2001;49(12):1700–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marin RS, Firinciogullari S, Biedrzycki RC. The sources of convergence between measures of apathy and depression. J Affect Disord. June 1993;28(2):117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starkstein SE, Manes F. Apathy and depression following stroke. CNSSpectr. March 2000;5(3):43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, Kremer J. Syndromic validity of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. June 2001;158(6):872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starkstein SE, Ingram L, Garau ML, Mizrahi R. On the overlap between apathy and depression in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. August 2005;76(8):1070–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, Robinson RG. The construct of minor and major depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. November 2005;162(11):2086–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta M, Whyte E, Lenze E, et al. Depressive symptoms in late life: associations with apathy, resilience and disability vary between young-old and old-old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. March 2008;23(3):238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starkstein SE, Mizrahi R, Garau L. Specificity of symptoms of depression in Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. September 2005;13(9):802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. April 4 2013;368(14):1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You SC, Walsh CM, Chiodo LA, Ketelle R, Miller BL, Kramer JH. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Predict Functional Status in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(3):863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Jul-Sep 2007;21(3):249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. Oct-Dec 2006;20(4):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr., Chance JM, Filos S Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. May 1982;37(3):323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spackman DE, Kadiyala S, Neumann PJ, Veenstra DL, Sullivan SD. The validity of dependence as a health outcome measure in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. May 2013;28(3):245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. Spring 2000;12(2):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings JL, McPherson S. Neuropsychiatric assessment of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Aging (Milano). June 2001;13(3):240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radakovic R, Harley C, Abrahams S, Starr JM. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of apathy scales in neurodegenerative conditions. Int Psychogeriatr. June 2015;27(6):903–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. November 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chow GC. Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica. 1960;28:591–605. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marin RS. Differential diagnosis and classification of apathy. Am J Psychiatry. January 1990;147(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]