Abstract

Background:

Lung transplant (LTx) recipients have low long-term survival and a high incidence of bronchiolitis-obliterans syndrome (BOS). However, few long-term, multicenter, and precise estimates of BOS-free survival (a composite outcome of death and BOS) incidence exist.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study of primary LTx recipients (1994–2011) reported to the ISHLT Thoracic Transplant Registry assessed outcomes through 2012. For the composite primary outcome of BOS-free survival, we used Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox proportional hazards regression, censoring for loss-to-follow-up, end-of-study, and retransplantation. While standard Registry analyses censor at the last consecutive annual complete BOS status report, our analyses allowed for partially missing BOS data.

Results:

Due to BOS reporting standards, 99.1% of the cohort received LTx in North America. During 79,896 person-years of follow-up, single LTx (6,599/15,268; 43%) and bilateral LTx (8,699/15,268; 57%) recipients had a median BOS-free survival of 3.16 (95% CI, 2.99–3.30) years and 3.58 (95% CI, 3.53–3.72) years, respectively. Almost 90% of the single and bilateral LTx recipients developed the composite outcome within 10 years of transplantation. Standard Registry analyses “overestimated” median BOS-free survival by 0.42 years and “underestimated” the median survival after BOS by about a half-year for both single and bilateral LTx (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

A majority of LTx recipients die or develop BOS within 4 years, and very few remain alive and free from BOS at 10 years post-transplantation. Less inclusive Registry analytic methods tend to overestimate BOS-free survival. The Registry would benefit from improved international reporting of BOS and other chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) events.

INTRODUCTION

Lung transplantation (LTx) recipients have 1-, 5-, and 10-year unadjusted survival rates of 80%, 54%, and 32%, respectively.1 Chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) causes most deaths after the first post-transplant year,1–3 and most CLAD has an obstructive phenotype known as bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS).4 Obliterative bronchiolitis (OB), the histologic hallmark of BOS, consists of a fibrotic luminal obliteration of the respiratory and terminal bronchioles.5 The patchy nature of OB reduces the diagnostic sensitivity of transbronchial lung biopsies. Thus, clinicians use a thoroughly explored and unexplained drop in lung function to diagnose BOS, the surrogate of OB.3,6–8 CLAD also includes a less common, restrictive phenotype known as restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS),2,3,9–11 and some LTx recipients have a combined syndrome of RAS and BOS.3

Many studies and Registry analyses have reported the incidence or prevalence of BOS, and freedom from BOS after LTx.1,12–15 However, incidence estimates of BOS and Kaplan-Meier estimates of freedom from BOS ignore an important and frequent competing event (i.e., death). Utilizing BOS-free survival after LTx allows the incorporation of both the death and BOS endpoints into a composite post-LTx outcome, and provides a much more robust estimate than either of its components.16–22 Surprisingly, only a few single-center or small multi-center cohort studies15,23,24 have reported long-term BOS-free survival rates, and these studies have not used uniform methodology or reporting.25–27 As a result, estimates of BOS-free survival have varied widely, ranging from 34–75% at 5 years.26,28,29 Importantly, since the remaining native lung in a single LTx recipient may influence the accuracy of the BOS diagnosis,30,31 and single and bilateral LTx have different death and BOS incidences,32–34 studies should be reporting these outcomes stratified by transplant procedure type. Yet, limited data exist regarding BOS-free survival rates in subgroups of LTx recipients, such as those receiving single versus bilateral LTx.20,35,36

Given the knowledge gaps regarding BOS-free survival, we conducted this study to estimate its incidence in adult primary LTx recipients and stratified the analyses by transplant procedure type. We used more data-inclusive methods than those used in the Registry’s annual reports to assess the effects of the assumptions made by the Registry about the presence or absence of BOS and its occurrence date.37–40 Since stakeholders may use data from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Thoracic Transplant Registry as benchmarks or for clinical trial planning,41,42 we compared effects of different approaches for handling partially missing data on BOS-free survival.

METHODS

Study design

Using data provided by the multinational ISHLT Thoracic Transplant Registry (www.ishlt.org/registries/) via a data sharing agreement, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of LTx reported during the era January 1, 1994 to December 31, 2011. We assessed follow-up data reported through December 31, 2012 (Supplement). The Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office/Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt since it utilized de-identified data.

Data Source

National and multinational organ/data exchange organizations (“collectives”) and individual centers outside of collectives may voluntarily submit data to the Registry. Since its inception, almost 250 LTx centers have reported data to the Registry.1 The Registry requires participating collectives/centers to report Tier 1 data elements, such as death, whereas they do not require reporting of the optional Tier 2 data elements such as BOS (Supplementary Table 1; https://www.ishlt.org/registries/heartLungRegistry.asp).

Participants and Study Eligibility Criteria

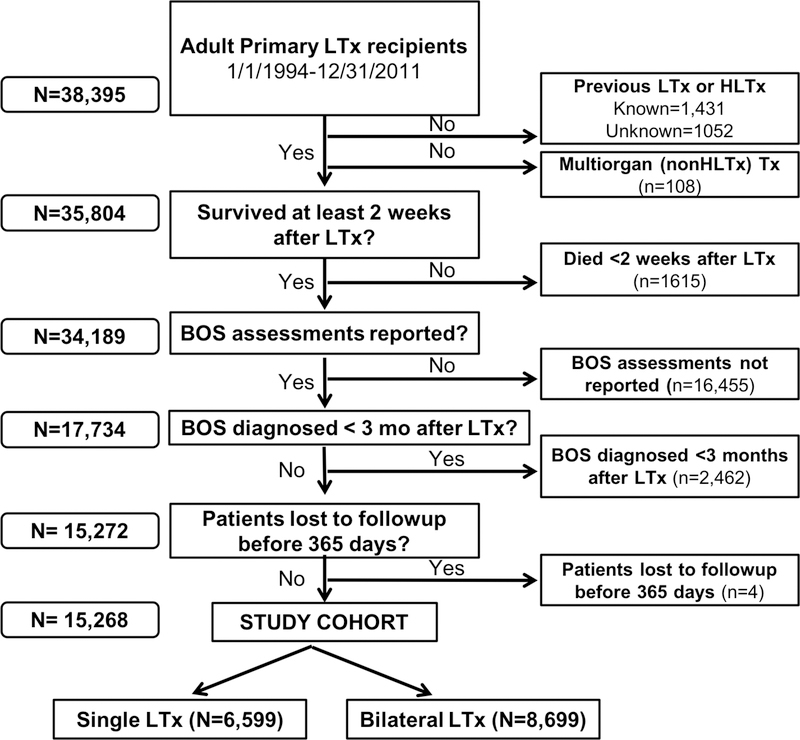

We analyzed Registry data for all adult LTx reported during the study era. Figure 1 shows the study eligibility criteria and the derivation of the study cohort. The Supplement provides details regarding methods to minimize bias and to determine “patient status” (‘living’, ‘dead’, ‘lost to follow-up’, or ‘retransplanted’) at the time of follow-up.1,37–40

Figure 1: Derivation of study cohort from the ISHLT Thoracic Transplant Registry.

Flowchart of lung transplant recipients and application of eligibility criteria that resulted in the final study cohort that we stratified by transplant procedure type. BOS assessments “not reported” refers to sites or transplant collectives that do not report BOS information as part of their standard data reporting. *LTx= lung transplantation; Tx=transplantation; HLTx=heart-lung transplantation; BOS=bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.

Outcomes

We used BOS-free survival as the primary outcome variable. A LTx recipient achieves the composite outcome if either BOS or death occur, whichever comes first (Supplement). Each transplant center determines if and when BOS has occurred. The Registry does not validate the BOS diagnosis. The Registry records BOS status (i.e., ‘yes’ [present] or ‘no’ [absent]) information during each post-transplant reporting period (i.e., transplant hospitalization and annually thereafter), but does not collect a specific date for BOS (Supplement). The Registry also does not formally collect data for the broader term “CLAD”.8,39

The Registry receives death status information on all patients during each reporting period. However, unlike BOS, death reporting includes the date of death. Thus, the time of death has more precision than the time of BOS (Supplement).

Statistical Methods

This study analyzed the BOS status and event time data in ways that differ from the annual report.1,37–40 For time to event analyses that use BOS as part (i.e., BOS-free survival) or all (freedom from BOS) of the primary outcome, the Registry had typically censored BOS data at the time of the last consecutive follow-up that reported “no BOS” (Scenario 1; Table 1).1,37–40 For this study, we made clinically reasonable assumptions about missing data in the setting of consistent reporting (Scenario 2; Table 1). For Scenario 1 (typical Registry methodology) and Scenario 2 (this study’s methodology), we used the first report of “Yes BOS” as the endpoint for freedom from BOS analyses. Scenario 1 did not allow for missing responses, so it used consecutive reporting of BOS status to find the first report of “Yes BOS,” or it censored follow-up at the last consecutive report of “No BOS”. Scenario 1 used the midpoint of each reporting period as the date of BOS occurrence. In comparison, Scenario 2 allowed for a missing BOS response during one or more reporting periods, as long as the missing response(s) preceded a report with a “No BOS” or the first “Yes BOS” response. For the utilized “Yes BOS” events, Scenario 2 assumed that BOS occurred midway between the first “Yes BOS” and the previous “No BOS”.

Table 1:

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome status determination Scenarios and associated time to event calculations*

| Scenario 1 |

| Assumptions used for the annual Registry report (Allows for missing values prior to “NO BOS” or “YES BOS”) |

| • BOS status determined based on: |

| ○ Non-missing responses for BOS (YES/NO). |

| ○ If the first annual follow-up has a missing BOS response, then the LTx recipient becomes excluded from outcome assessments. |

| ○ Otherwise, at first missing response, BOS status is determined by the previous known responses. |

| • Follow-up time for time to BOS analyses: |

| ○ Use time to the first “YES BOS” follow-up if preceded by non-missing BOS response(s) of “NO BOS.” |

| ○ Otherwise, use time to the last consecutive “NO BOS.” |

| Scenario 2 |

| Assumptions used for this study Scenario 1 + allows for missing values prior to “NO BOS” or “YES BOS” |

| • BOS status determined based on: |

| ○ Non-missing responses for BOS (YES/NO), |

| ○ A “No BOS” response preceded by missing BOS (missing BOS response[s] prior to a “NO BOS” treated as “NO BOS”), or |

| ○ The “YES BOS” response preceded by any missing BOS response(s). |

| • Follow-up time for time to BOS analyses: |

| ○ Use time to the first “YES BOS” follow-up if preceded by non-missing BOS response(s) of “NO BOS.” |

| ○ Otherwise, use time to last “NO BOS.” |

| ○ If missing BOS values occur immediately prior to the first “Yes BOS”, then assume BOS occurred midway between the first “Yes BOS” and the last “No BOS.” |

Both BOS status determination Scenarios attempt to identify BOS based on the first reporting of “YES BOS.” Both Scenarios assume the LTx recipient has not been reported as dead to the Registry. Otherwise, death prior to the last follow-up used in each Scenario described above uses date of death for censoring in freedom from BOS analyses and for time of the event in BOS-free survival analyses.

Statistical Analysis

To describe the study cohort and its subgroups, we used descriptive statistics for continuous variables and counts and proportions for categorical variables. To compare baseline data among groups, we used Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous data and the Chi-Square test for categorical data. To estimate the incidence of events after transplant, we used time-to-event Kaplan-Meier analyses, and we censored for retransplant and last follow-up reported (end of study follow-up or loss to follow-up).40 We used the log-rank test to compare Kaplan-Meier curves between or among groups. Based on an a priori statistical analysis plan, we stratified the outcome data for LTx procedure type (i.e., single or bilateral).37 We compared estimates of BOS-free survival between the Scenarios with the Kruskal-Wallis test. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to adjust BOS-free survival analyses for factors associated with the outcome. We used SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) for statistical analyses and GraphPad Prism version 7.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA) for plotting. We defined statistical significance a priori for a P-value of <0.05. We did not adjust the critical p-value for multiple baseline comparisons between groups.

RESULTS

LTx Recipients and Study Eligibility

The ISHLT Registry query contained data from 38,395 adults who had a primary LTx reported in the 18-year study (Figure 1). Nearly half of the recipients had LTx at a site where the site or its collective did not report BOS to the Registry. When evaluating the three geographic regions typically described by the Registry, North America had the highest BOS reporting rate (84.5%), while Europe (0.13%) and Others (8.46%) had much lower rates. The study eligibility criteria produced a final cohort of 15,268 LTx recipients eligible for analysis (Figure 1). Of these, 15,135 (99.1%) of the LTx occurred at centers in in North America. Greater than 98% of eligible LTx recipients had the required BOS and survival status data available for analysis.

Of the 15,268 LTx recipient cohort, 6,599 (43.2%) received a single LTx and 8,669 (56.8%) received a bilateral LTx. Compared to single LTx recipients, bilateral LTx recipients had a 1) younger age, 2) more frequent use of life support going into transplantation, 3) high-risk behavior donor use, 4) female donor, 5) CMV mismatch status (recipient seronegative; donor seropositive), and 6) longer total ischemic time (Table 2). During the study era, the predominant LTx procedure switched from single LTx to bilateral LTx.

Table 2:

Cohort pre-transplant characteristics, stratified by procedure type

| Single LTx (N=6599) | Bilateral LTx (N=8669) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RECIPIENT | |||

| AGE AT TRANSPLANT | <0.0001 | ||

| Median (5th-95th percentile), years | 59.0 (43.0 – 69.0) | 50.0 (22.0 – 66.0) | |

| GENDER | 0.8026 | ||

| Female | 3001 (45.5%) | 3960 (45.7%) | |

| ABO BLOOD GROUP | 0.1784 | ||

| A | 2707 (41.0%) | 3574 (41.2%) | |

| AB | 252 (3.81%) | 356 (4.11%) | |

| B | 689 (10.4%) | 980 (11.3%) | |

| O | 2950 (44.7%) | 3759 (43.4%) | |

| Missing | 1 (.%) | 0 (.%) | |

| PRIMARY DIAGNOSTIC INDICATION FOR LTX | <0.0001 | ||

| COPD, non-A1ATD | 3245 (49.2%) | 2225 (25.7%) | |

| IIP | 2238 (33.9%) | 1739 (20.1%) | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 7 (0.11%) | 2183 (25.2%) | |

| COPD, A1ATD | 356 (5.39%) | 470 (5.42%) | |

| ILD, non-IIP | 208 (3.15%) | 255 (2.94%) | |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension | 45 (0.68%) | 351 (4.05%) | |

| Sarcoidosis | 126 (1.90%) | 322 (3.71%) | |

| All other diagnoses | 374 (5.67%) | 1123 (13.0%) | |

| Missing | 0 (.%) | 1 (.%) | |

| ERA OF TRANSPLANT | <0.0001 | ||

| 1/1/1994 through 12/31/2002 | 2938 (44.5%) | 2236 (25.8%) | |

| 1/1/2003- 12/31/2011 | 3661 (55.5%) | 6433 (74.2%) | |

| ON LIFE IMMEDIATELY PRIOR TO LTx | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 6393 (97.6%) | 7869 (91.6%) | |

| Yes | 158 (2.39%) | 724 (8.35%) | |

| Missing | 48 (.%) | 76 (.%) | |

| MOST RECENT PRA PERCENT - CLASS 1 | 0.2039 | ||

| Median (5th-95th), % | 0.0 (0.0 – 18.0) | 0.0 (0.0 – 25.0) | |

| MOST RECENT PRA PERCENT - CLASS 2 | 0.8872 | ||

| Median (5th-95th), % | 0.0 (0.0 – 23.0) | 0.0 (0.0 – 18.0) | |

| DONOR | |||

| AGE | 0.6085 | ||

| Median (5th-95th), years | 30.0 (15.0 – 57.0) | 30.0 (15.0 – 57.0) | |

| GENDER | <0.0001 | ||

| Female | 2411 (36.5%) | 3596 (41.5%) | |

| Male | 4188 (63.5%) | 5073 (58.5%) | |

| ABO BLOOD GROUP | 0.0067 | ||

| A | 2404 (36.4%) | 3227 (37.2%) | |

| AB | 129 (1.96%) | 203 (2.34%) | |

| B | 649 (9.83%) | 954 (11.0%) | |

| O | 3417 (51.8%) | 4285 (49.4%) | |

| HISTORY OF HIGH RISK BEHAVIOR | 0.0325 | ||

| No | 2917 (44.2%) | 5364 (61.9%) | |

| Yes | 199 (3.01%) | 442 (5.09%) | |

| Missing | 3483 (52.8%) | 2863 (33.0%) | |

| ISCHEMIC TIME FOR LAST LUNG IMPLANTED | <0.0001 | ||

| Median (5th-95th), hours | 3.9 (2.0 – 6.3) | 5.4 (3.1 – 8.4) | |

| DONOR / RECIPIENT CMV STATUS | <0.0001 | ||

| Negative / Negative | 883 (13.4%) | 1544 (17.8%) | |

| Negative / Positive | 1557 (23.6%) | 1609 (18.6%) | |

| Positive / Negative (“mismatch”) | 1177 (17.8%) | 2001 (23.1%) | |

| Positive / Positive | 2391 (36.2%) | 2727 (31.5%) | |

| Missing | 591 (8.96%) | 788 (9.09%) | |

After excluding missing cases, P-values calculated using Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. IIP limited to those with a diagnosis of “UIP/IPF” in the ISHLT Registry. Abbreviations: A1ATD, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IIP, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; PRA, panel reactive antibody; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonitis.

Follow-up after LTx

The study cohort had 79,896 person-years of follow-up (single LTx 33,934 person-years; bilateral LTx, 45,962 person-years). The cohort had only 279/15,268 (1.83%) cases lost to follow-up prior to the study end date, and the lost events typically occurred after years of reported follow-up (median: 4.76; interquartile range, 4.02 years).

Post-lung transplantation outcomes

BOS-free survival

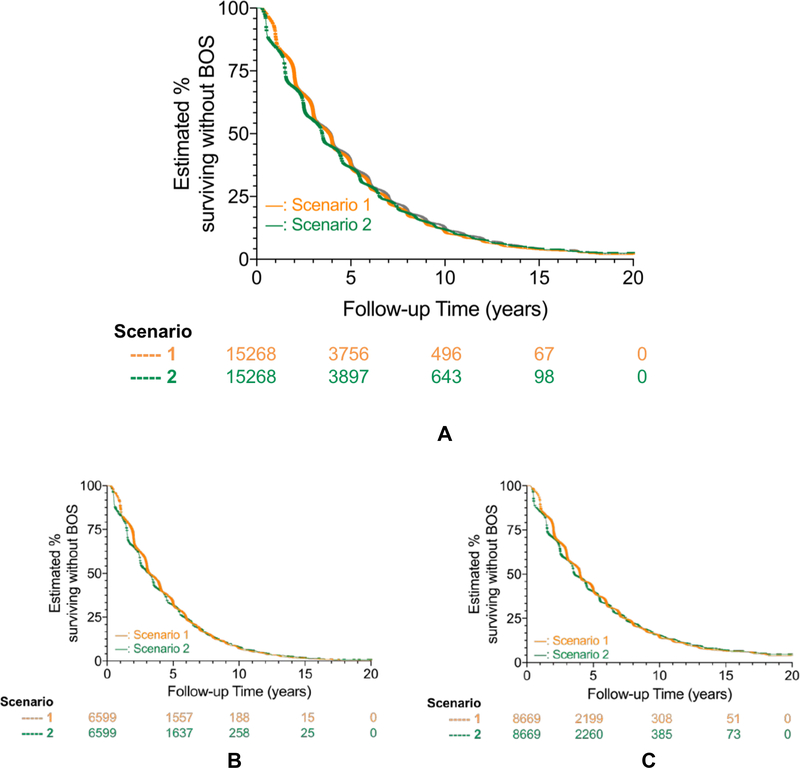

A majority of LTx recipients developed the composite outcome (death or BOS, whichever occurred first) within 4 years after transplantation (Figure 2A-C) and almost 90% developed the composite outcome within 10 years of transplantation (Figure 2A, Table 3A). The median time to BOS-free survival for bilateral LTx was 4.00 years when using Scenario 1, the approach typically used by the Registry, compared to 3.58 years when using Scenario 2, which accounted for partially missing BOS data. In comparison, the median time to BOS-free survival for single LTx was 3.19 years (Scenario 1) compared to 3.16 years (Scenario 2) (p<0.001 for bilateral vs single LTx in each Scenario; Figure 2A, Table 3A).

Figure 2: BOS-free survival after lung transplantation, overall and stratified by transplant procedure type.

Kaplan-Meier survival methods estimated the proportion in whom bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) and death had not occurred at follow-up after lung transplantation (LTx), stratified by the two BOS status determination Scenarios [Scenario 1 (orange) versus Scenario 2 (green); see Table 1 for Scenario definitions] that we used to determine the presence of absence of BOS. Numbers below X-axis time points represent those at risk.

Cohorts consisted of primary LTx reported from 1/1/1994 to 12/31/2011, with outcomes assessed through 12/31/2012. Analyses censored for retransplant, end of study follow-up, and loss to follow-up (i.e., used the mid-point of the reporting period last reported as alive).

Figure 2A shows unadjusted BOS-free survival in the entire eligible study cohort (Single LTx and Bilateral LTx combined), while Figures 2B and 2C show estimates stratified by transplant procedure type (Single LTx, Figure 2B; Bilateral LTx, Figure 2C). Single LTx and bilateral LTx recipients had a median time to BOS or death of 3.2 for Scenario 1 to 3.3 years for Scenario 2, and 3.6 years for Scenario 1 to 4.0 years for Scenario 2 respectively. For each Scenario, bilateral LTx had greater BOS-free survival than single LTx (log rank p < 0.001).

Table 3A:

Kaplan-Meier BOS-free survival after primary lung transplantation

| BOS-free survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year* | 3 year* | 5 year* | 10 year* | Mediana | |

| Bilateral Lung Transplant (n=8,699)% (95% CI) | |||||

| Scenario 1b | 90.2 | 61.3 | 41.3 | 14.3 | 4.00 years |

| (89.6–90.9) | (60.3–62.4) | (40.2–42.5) | (13.2–15.5) | (3.98–4.03) | |

| Scenario 2b | 85.3 | 58.3 | 40.0 | 15.3 | 3.58 years |

| (84.6–86.1) | (57.3–59.4) | (38.9–41.1) | (14.2–16.4) | (3.53–3.72) | |

| Single Lung Transplant (n=6,599)% (95% CI) | |||||

| Scenario 1b | 88.0 | 54.8 | 32.8 | 7.1 | 3.19 years |

| (87.2–88.8) | (53.5–56.0) | (31.6–34.1) | (6.19–7.94) | (3.09–3.40) | |

| Scenario 2b | 83.1 | 51.2 | 31.7 | 7.8 | 3.16 years |

| (82.1–84.0) | (49.9–52.4) | (30.5–32.9) | (7.01–8.67) | (2.99–3.30) | |

| Single or Bilateral Lung Transplant (n=15,268)% (95% CI) | |||||

| Scenario 1b | (88.8–89.8) | (57.7–59.3) | (36.7–38.4) | (10.0–11.5) | (3.75–3.91) |

| 89.3 | 58.5 | 37.5 | 10.8 | 3.84 years | |

| Scenario 2b | 84.4 | 55.2 | 36.3 | 11.6 | 3.48 years |

| (83.8–84.9) | (54.4–56.0) | (35.5–37.1) | (10.9–12.3) | (3.45–3.50) | |

BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CI, confidence interval.

Composite outcome event: BOS or death, whichever comes first.

Censoring: retransplant, end of study or loss to follow-up.

Values denote cumulative percent (95% CI) without the composite outcome.

Median time to composite outcome (95%CI).

BOS status determination Scenario definitions shown in Table 1.

Single LTx recipients had significantly worse unadjusted BOS-free survival than bilateral LTx recipients, regardless of the Scenario used to determine BOS status (for both Scenarios, HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.24–1.34; log-rank test p<0.001; Table 3A, Figure 2B and 2C, Supplementary Figure 1), and the divergence in BOS-free survival between the single and bilateral LTx groups widened during follow-up.

To compare BOS-free survival between lung transplant procedure types, we adjusted for baseline (time of transplant) variables that have a known impact on BOS and survival, focusing on Tier 1 elements that had complete data in the Registry. After adjusting for recipient age at transplant, gender, era and primary diagnostic indication for transplantation, only transplant procedure type had a significant association with BOS-free survival. Both Scenarios showed similar results favoring bilateral over single LTx (for single LTx, Scenario 1 HRadj 1.32, 95% CI 1.26–1.38, p <0.001; Scenario 2 HRadj 1.31, 95% CI 1.25–1.37, p <0.001).

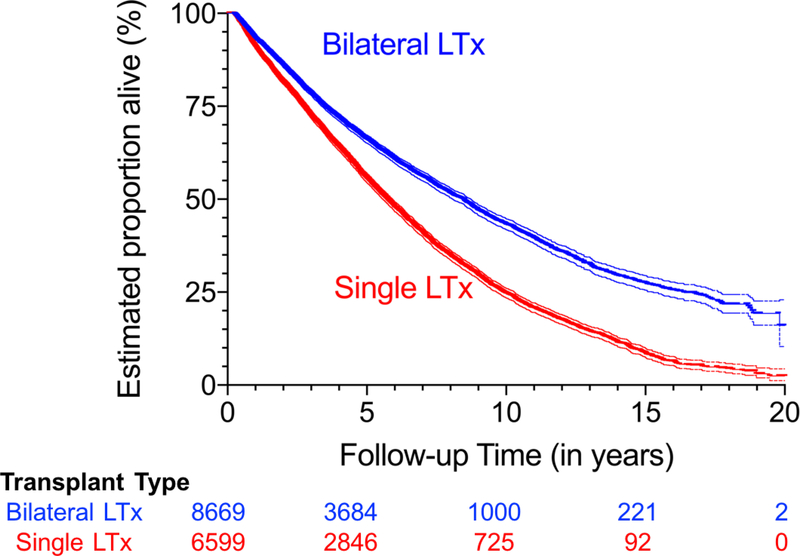

Death and BOS

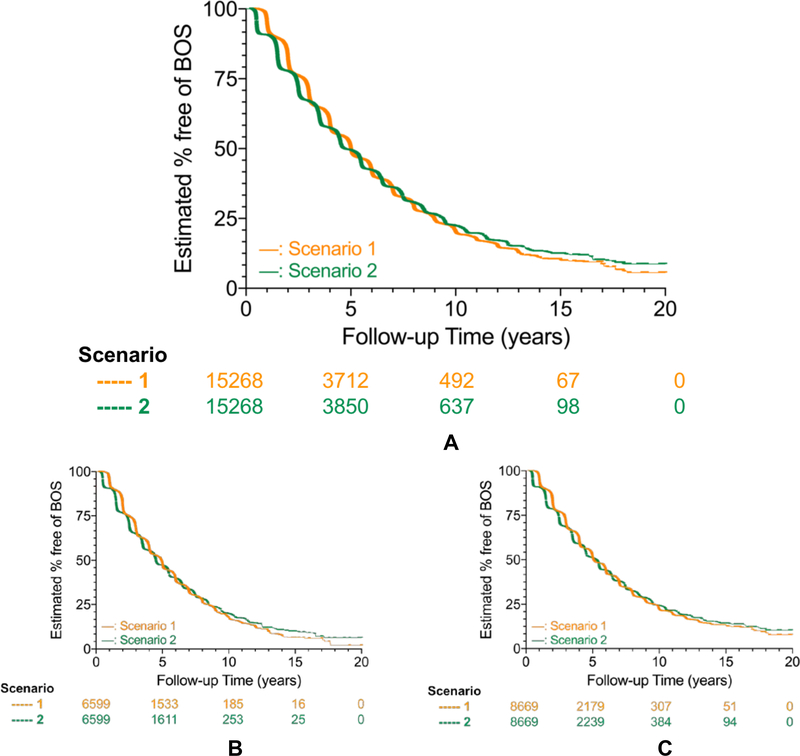

Regarding composite endpoint components, 46.8% (8,128/15,268) of the recipients died during the observational period, with nearly 40% of the deaths occurring within 5 years after LTx (Figure 3, Table 3B). Median time to death was 5.75 years for single LTx recipients compared to 8.48 years for bilateral LTx recipients (p<0.0001, Figure 3, Table 3B). Among those who lived for 10 years after LTx, almost all developed BOS (Figure 4A-C). The median time to BOS after LTx ranged from 5.00 for Scenario 1 to 4.67 years for Scenario 2 (p<0.0001 for both single and bilateral LTx; Figure 4A, Table 3C).

Figure 3: Survival after lung transplantation, stratified by transplant procedure type.

Kaplan-Meier survival for single and bilateral lung transplant (LTx). Cohorts consisted of primary LTx reported from 1/1/1994 to 12/31/2011, with outcomes assessed through 12/31/2012. Analyses censored for retransplant, end of study follow-up, and loss to follow-up (i.e., used the mid-point of the reporting period last reported as alive), but not censored for BOS.

Bilateral LTx (blue) had better unadjusted survival than single LTx (red), and the discrepancy became larger during follow-up (log-rank test p < 0.001; unadjusted hazard ratio for death in single LTx versus bilateral LTx 1.56 [95% CI 1.49–1.63]). Thin lines surrounding each curve represent the upper and lower 95% CI limits.

Table 3B:

Kaplan-Meier survival after primary lung transplantation

| Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year* | 3 year* | 5 year* | 10 year* | Mediana | |

| Bilateral Lung Transplant (n=8,699)% (95% CI) | |||||

| All Scenariosb | 93.5 | 78.8 | 66.2 | 43.3 | 8.48 years |

| (93.0–94.1) | (77.9–79.7) | (65.1–67.3) | (41.9–44.8) | (8.09–8.73) | |

| Single Lung Transplant (n=6,599)% (95% CI) | |||||

| All Scenariosb | 91.3 | 72.8 | 55.8 | 24.7 | 5.75 years |

| (90.6–92.0) | (71.8–74.0) | (54.5–57.0) | (23.4–26.1) | (5.57–5.92) | |

| Single or Bilateral Lung Transplant (n=15,268)% (95% CI) | |||||

| All Scenariosb | 92.5 | 76.2 | 61.5 | 34.1 | 6.83 years |

| (92.1–93.0) | (75.5–76.9) | (60.7–62.3) | (33.0–35.1) | (6.69–7.02) | |

CI, confidence interval.

Outcome event: death.

Censoring: retransplant, end of study, or loss to follow-up.

Values denote cumulative percent (95% CI) alive.

Median time to death (95%CI).

All BOS Scenarios use the same survival data.

Figure 4: Freedom from BOS after lung transplantation, overall and stratified by transplant procedure type.

Kaplan-Meier survival methods estimated the proportion in whom bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) had not occurred at follow-up after lung transplantation (LTx), stratified by the two BOS status determination Scenarios [Scenario 1 (orange) versus Scenario 2 (green); see Table 1 for Scenario definitions] used for determining the BOS status (present or absent). Numbers below X-axis time points represent those at risk.

Cohorts consisted of primary LTx reported from 1/1/1994 to 12/31/2011, with outcomes assessed through 12/31/2012. Analyses censored for death, retransplant, end of study follow-up, and loss to follow-up (i.e., used the mid-point of the reporting period last reported as alive).

Figure 4A shows estimates of overall freedom from BOS in the entire eligible study cohort (Single LTx and Bilateral LTx combined), while Figures 4B and 4C show estimates stratified by transplant procedure type (Single LTx; Figure 4B; Bilateral LTx, Figure 4C).

For each Scenario, bilateral LTx had greater freedom from BOS than single LTx (log rank p < 0.001). For each Scenario, single LTx recipients had a shorter median time to BOS than bilateral LTx recipients, with the median time to BOS ranging from 0.14 years (Scenario 1) to 0.78 years (Scenario 2).

Table 3C:

Kaplan-Meier Freedom from BOS after primary lung transplantation

| Freedom from BOS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year* | 3 year* | 5 year* | 10 year* | Mediana | |

| Bilateral Lung Transplant (n=8,699)% (95% CI) | |||||

| Scenario 1b | 95.6 (95.1–96.1) | 71.3 (70.3–72.4) | 52.1 (50.9–53.4) | 22.3 (20.7–23.9) | 5.06 years (5.02–5.23) |

| (95.1–96.1) | (70.3–72.4) | (50.9–53.4) | (20.7–23.9) | (5.02–5.23) | |

| Scenario 2b | 90.7 (90.1–91.4) | 68.4 (67.4–69.5) | 51.1 (49.8–52.3) | 24.1 (22.6–25.7) | 5.29 years (4.92–5.42) |

| (90.1–91.4) | (67.4–69.5) | (49.8–52.3) | (22.6–25.7) | (4.92–5.42) | |

| Single Lung Transplant (n=6,599)% (95% CI) | |||||

| Scenario 1b | 95.3 | 68.4 | 47.9 | 17.5 | 4.92 years |

| (94.7–95.8) | (67.1–69.7) | (46.4–49.4) | (15.8–19.3) | (4.80–4.99) | |

| Scenario 2b | 90.4 | 64.8 | 47.1 | 19.7 | 4.51 years |

| (89.6–91.1) | (63.6–66.1) | (45.7–48.6) | (18.0–21.3) | (4.46–4.56) | |

| Single or Bilateral Lung Transplant (n=15,268)% (95% CI) | |||||

| Scenario 1b | 95.5 | 70.1 | 50.3 | 20.2 | 5.00 years |

| (95.1–95.8) | (69.3–70.9) | (49.3–51.3) | (19.0–21.4) | (4.98–5.04) | |

| Scenario 2b | 90.6 | 66.9 | 49.4 | 22.2 | 4.67 years |

| (90.1–91.1) | (66.1–67.7) | (48.5–50.3) | (21.1–23.3) | (4.56–5.10) | |

BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CI, confidence interval.

Outcome event: BOS.

Censoring: death, retransplant, end of study or loss to follow-up.

Values denote cumulative percent (95% CI) without BOS.

Median time to BOS (95%CI).

BOS status determination Scenario definitions shown in Table 1.

Comparison of methodologies for using data from LTx recipients who have missing BOS status

BOS-free survival

Different Scenarios for using data from LTx recipients who had missing BOS status during any eligible follow-ups produced significantly different outcomes for each transplant procedure type (Supplementary Table 2A-C). For example, Scenario 1, the approach typically used by the Registry, yielded significantly higher BOS-free survival by about 5% at 1 year and by about 3% at 3 years for each of the single and bilateral LTx groups, in comparison to Scenario 2, which accounted for partially missing BOS data (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2A). There was no overlap in the 95% confidence intervals for 1- and 3-year BOS-free survival between Scenario 1 and 2 (Supplementary Table 2A). Scenario 1 also had a significantly higher median BOS-free survival time when compared to Scenario 2 (e.g., for bilateral LTx, 0.42 years longer; Supplementary Table 2A). These Scenario differences in BOS-free survival occurred mainly in the first 4 years post-transplantation (Figure 2B-C, Supplementary Table 2A) and became less apparent at later time points.

Survival

By definition, the Scenarios used to determine BOS had no effect on survival. Single LTx recipients had significantly worse survival (2.7 year lower median survival; HRadj for death 1.45, 95% CI 1.37–1.53; p<0.001; Figure 3, Table 3B; Supplementary Table 2B) compared to the bilateral LTx recipients.

Freedom from BOS

Regardless of the Scenario used, single LTx recipients had significantly worse unadjusted freedom from BOS compared to bilateral LTx recipients (Scenario 1, HR for BOS 1.14, 95% CI 1.09–1.19; p<0.001; Scenario 2, HR for BOS 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.18; Figure 4B and C, Table 3C) compared to the bilateral LTx recipients and had a shorter median time to BOS (0.14 years; Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2C). This discrepancy became even more apparent with Scenario 2 analyses (0.78 years) (Table 3C, Figure 4B and C). Both Scenarios showed similar results favoring bilateral over single LTx when adjusted for age at transplant, gender, diagnosis and era (for single LTx, Scenario 1 HRadj 1.29, 95% CI 1.16–1.30, p <0.001; Scenario 2 HRadj 1.21, 95% CI 1.15–1.28, p <0.001).

Post-BOS survival

After the diagnosis of BOS, LTx recipients had a low Kaplan-Meier survival. Bilateral LTx recipients had a longer median survival time than single LTx recipients, with Scenario 1 having at least half-a-year lower survival than Scenario 2 for both transplant procedure types (Bilateral LTx, Scenario 1, 3.8 years and Scenario 2, 4.3 years; Single LTx Scenario 1, 2.6 years, and Scenario 2, 3.1 years; Supplementary Table 3). Given the incompleteness of BOS stage reporting, we did not analyze outcomes based on BOS stage at first BOS diagnosis, trajectory of BOS stages, or effect of treatments on the development of BOS.

DISCUSSION

To address long-term outcomes in lung transplant recipients, we utilized the data from the ISHLT Thoracic Transplant Registry, which uses a type of real-world evidence data, which when compared to clinical trial data, can more closely describe how a technology will perform in a broader, more representative population over a longer timeframe.43 This analysis of this Registry data demonstrated the disappointingly high incidence of both death and BOS, and consequently low BOS-free survival for recipients of primary LTx. The majority of single and bilateral LTx recipients had BOS or death reported within 4 years after LTx, and almost 90% of recipients experienced at least one of these outcomes within 10 years after LTx.

We believe that standard Registry LTx recipient analyses (Scenario 1) overestimate BOS-free survival produced by not utilizing data after a recipient’s first missing report of BOS status.1,38–40 In comparison to our analytic approach (Scenario 2) that incorporated some common sense assumptions, we detected that Scenario 1 significantly “overestimated” BOS-free survival by about 5% at 1 year and about 3% at 3 years for both of the single and bilateral LTx groups. Also, compared to our approach, Scenario 1 significantly “overestimated” the median BOS-free survival time by 0.42 years for bilateral LTx and by 0.03 years for single LTx and “underestimated” the median survival after BOS by about a half-year for both procedure types.

The majority of previous multicenter cohort studies and Registry analyses have focused on freedom from BOS and/or overall survival rather than BOS-free survival.1,14,44,45 This study demonstrated the important discrepancy between freedom from BOS and BOS-free survival. Since freedom from BOS Kaplan-Meier analyses censor for death and BOS-free survival analyses include death as part of the composite endpoint,21,46 the freedom from BOS analyses have much better outcomes than the BOS-free survival analyses. For example, even at 3 years after LTx, freedom from BOS was 70%, while BOS-free survival was only 55%, and this disparity increased during follow-up. This demonstrates the importance of incorporating survival when presenting outcome data.

Limited data exists regarding BOS-free survival in single and in bilateral LTx recipients. 20,35,36 In addition, the few studies that have assessed BOS-free survival have not generated consistent estimates, with the estimates varying from 34–75% at 5 years post-LTx.26,28,29 We found that only 31.7% of single LTx and 40.0% of bilateral LTx recipients (36.3% for all LTx) remained alive and free from BOS at 5 years post-LTx. While a component of BOS may be reversible upon use of azithromycin, the first randomized placebo-controlled trial of azithromycin to prevent BOS was published in 2011.36 As our a priori study cohort was defined as those receiving a primary LTx in the era of 1/1/1994 through 12/31/2011, and recipient outcome assessment through 12/31/2012, it is extremely unlikely that a significant proportion of patients in our study were treated with chronic azithromycin to prevent BOS, since that practice only began gaining acceptance around the end of this study.47,48 Even if centers did start giving azithromycin when lung function began to drop, it likely would have affected only a small proportion of the cohort since most patients had died or developed BOS by 2011. However, going forward, the use of azithromycin needs to be considered when interpreting long-term outcomes associated with BOS and/or CLAD.6

Previous Registry data assessments32,33 and other studies18–20,35,36 have found a strong association between transplant procedure type and survival after LTx. This study provides new and robust data about BOS-free survival, adjusts for important baseline covariates and reinforces the discrepancy in outcomes between bilateral over single lung transplantation. Moreover, as the Registry data uses a type of real-world evidence data, local and patient-specific clinical practice (and not a rigid study protocol) determine diagnostic and treatment decision-making in this real-world setting.49 Thus, secondary real-world evidence data obtained from Registries support retrospective analyses which may serve as inputs for prospective study designs.50

This study of LTx that occurred over 18 years had 79,896 person-years of follow-up, and more than 98% of recipients had follow-up that allowed for assessment of the composite endpoint. Despite the large sample size of more than 15,000 recipients that included a majority of the world’s lung transplants during the study era, and the apparent precision of our estimates, we recognize limitations of Registry data analyses. Accuracy and precision tradeoffs include: 1) the lack of an exact date of BOS and assumptions about the timing of BOS, 2) lack of validation of the BOS diagnosis, 3) a significant amount of missing BOS stage information at the time of first BOS diagnosis, and 4) BOS trajectory information.20 Regarding the limitations of the multivariable analyses, we restricted it to variables from the Tier 1 mandatory reporting elements that we thought might influence BOS-free survival; we did not include factors51,52 that had a large amount of missing data. We did not have the ability to significantly assess for predictor variable data accuracy, though we attempted to assess some broad categories (such as primary diagnostic indication) to decrease the risk of misclassification.37 We also did not have the option of including any variables that the Registry does not collect.

Regarding the primary composite outcome, we used the narrower outcome of BOS instead of CLAD because the Registry does not specifically collect CLAD data. However, some “yes BOS” status reporting may actually refer to non-BOS CLAD events.8,39 Since CLAD includes BOS and restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS), the latter often having worse outcomes and treatment response compared to BOS,10,11,4 the BOS-free survival estimates likely underestimated CLAD-free survival. However, given the very low BOS-free survival shown in this study, any worse estimates of CLAD-free survival do not change the bleak picture that begs for improvement. Additionally, this study did not assess for causes of death, as we did not aim to do so. The Registry’s annual reports already provide cause of death information.1 Moreover, in our study, we would argue that the cause of death did not matter as we mainly wanted capture that a death occurred as an absolute competing event to BOS. As an aside, cause of death determination, even when assessed by blinded central adjudication, has significant validity concerns.53

This Registry study utilized data that came almost exclusively from the U.S. and Canada. The lack of non-North American data in the Registry has resulted mainly from a combination of lack of BOS data collection by collectives and a lack of center reporting of BOS data to the Registry. Though the lack of non-North American BOS data in the Registry decreases the generalizability of this study, it does not affect its internal validity. Supporting the external validity of this study, the cohort likely included more than half of all LTx performed internationally. For example, in 2016, 55% (2,818/5,147) of the world’s LTx occurred in the U.S. and 6% (302/5,147) occurred in Canada.54 Thus, this study generalizes to about two-thirds of the world’s LTx recipients.

To summarize, despite its limitations, this large study: 1) provides robust estimates of BOS-free survival, 2) describes the precision of these estimates, 3) shows the important differences between BOS-free survival and freedom from BOS, 4) points out the important effects of handling missing data, and 5) describes a clinically relevant association between transplant procedure type and BOS-free survival. The findings from this study support the vital need for new therapies to improve post-transplant survival and to reduce the incidence of BOS and other types of CLAD. Accordingly, we strongly advocate for expanded CLAD data collection by the Registry, the data collectives, and individual transplant centers. We propose that clinical trials of therapeutics aimed at mitigating CLAD or any of its subtypes should use event-free survival as a primary endpoint.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Leah Edwards and Jaime Williamson for assistance with the ISHLT Registry dataset.

Funding information: Research reported in this publication is supported by an ISHLT Transplant Registry Early Career Award and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant for the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (3UL1 TR000448) to HSK. Salary support (HSK) provided by an NIH Training grant in the Principles of Pulmonary Research (5T32-HL007317) and NIH Training grant in the Immunobiology of Rheumatic Diseases (5T32-AR007279).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chambers DC, Yusen RD, Cherikh WS, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fourth Adult Lung And Heart-Lung Transplantation Report-2017; Focus Theme: Allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:1047–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd JL, Jain R, Pavlisko EN, et al. Impact of forced vital capacity loss on survival after the onset of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verleden GM, Raghu G, Meyer KC, Glanville AR, Corris P. A new classification system for chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verleden GM, Vos R, Verleden SE, et al. Survival determinants in lung transplant patients with chronic allograft dysfunction. Transplantation. 2011;92:703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke CM, Theodore J, Dawkins KD, et al. Post-transplant obliterative bronchiolitis and other late lung sequelae in human heart-lung transplantation. CHEST. 1984;86:824–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer KC, Raghu G, Verleden GM, et al. An international ISHLT/ATS/ERS clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1479–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper JD, Billingham M, Egan T, et al. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature and for clinical staging of chronic dysfunction in lung allografts. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verleden SE, Ruttens D, Vandermeulen E, et al. Elevated bronchoalveolar lavage eosinophilia correlates with poor outcome after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97:83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodrow JP, Shlobin OA, Barnett SD, Burton N, Nathan SD. Comparison of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome to other forms of chronic lung allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1159–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato M, Waddell TK, Wagnetz U, et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS): a novel form of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittle GJ, Sanchez PG, Kon ZN, et al. The use of lung donors older than 55 years: a review of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes D, Black SM, Tobias JD, et al. Influence of human leukocyte antigen mismatching on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes D, Kopp BT, Kirkby SE, et al. Impact of Donor Arterial Partial Pressure of Oxygen on Outcomes After Lung Transplantation in Adult Cystic Fibrosis Recipients. Lung. 2016;194:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raghavan D, Gao A, Ahn C, et al. Lung transplantation and gender effects on survival of recipients with cystic fibrosis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:1487–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verleden SE, Sacreas A, Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden GM. Advances in Understanding Bronchiolitis Obliterans After Lung Transplantation. CHEST. 2016;150:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hennessy SA, Hranjec T, Emaminia A, et al. Geographic distance between donor and recipient does not influence outcomes after lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1847–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeriouh M, Mohite PN, Sabashnikov A, et al. Lung transplantation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: long-term survival, freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, and factors influencing outcome. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neurohr C, Huppmann P, Thum D, et al. Potential functional and survival benefit of double over single lung transplantation for selected patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transpl Int. 2010;23:887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finlen Copeland CA, Snyder LD, Zaas DW, Turbyfill WJ, Davis WA, Palmer SM. Survival after bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome among bilateral lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:784–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HT, Armand P. Clinical endpoints in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation studies: the cost of freedom. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:860–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusen RD. Lung transplantation outcomes: the importance and inadequacies of assessing survival. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1493–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strueber M, Warnecke G, Fuge J, et al. Everolimus Versus Mycophenolate Mofetil De Novo After Lung Transplantation: A Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label Trial. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:3171–3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon GS, Valentine VG, Levitt J, et al. Clarithromycin for prevention of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in lung allograft recipients. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton CM, Carlsen J, Mortensen J, Andersen CB, Milman N, Iversen M. Long-term survival after lung transplantation depends on development and severity of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitson BA, Prekker ME, Herrington CS, et al. Primary graft dysfunction and long-term pulmonary function after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:1004–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato M, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Saito T, et al. Time-dependent changes in the risk of death in pure bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luckraz H, Sharples L, McNeil K, Wreghitt T, Wallwork J. Cytomegalovirus antibody status of donor/recipient does not influence the incidence of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomaszek SC, Fibla JJ, Dierkhising RA, et al. Outcome of lung transplantation in elderly recipients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouwens JP, van der Bij W, van der Mark TW, et al. The value of ventilation scintigraphy after single lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verleden GM, Dupont LJ, Delcroix M, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide after lung transplantation: impact of the native lung. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thabut G, Christie JD, Ravaud P, et al. Survival after bilateral versus single lung transplantation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective analysis of registry data. Lancet. 2008;371:744–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer DM, Bennett LE, Novick RJ, Hosenpud JD. Single vs bilateral, sequential lung transplantation for end-stage emphysema: influence of recipient age on survival and secondary end-points. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadjiliadis D, Chaparro C, Gutierrez C, et al. Impact of lung transplant operation on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valentine VG, Robbins RC, Berry GJ, et al. Actuarial survival of heart-lung and bilateral sequential lung transplant recipients with obliterative bronchiolitis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:371–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden SE, et al. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin to prevent chronic rejection after lung transplantation. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Dipchand AI, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-third Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Report-2016; Focus Theme: Primary Diagnostic Indications for Transplant. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:1170–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusen RD, Christie JD, Edwards LB, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirtieth adult lung and heart-lung transplant report−−2013; focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:965–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-second Official Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report−−2015; Focus Theme: Early Graft Failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1264–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-first adult lung and heart-lung transplant report−−2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:1009–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartwig MG, Snyder LD, Appel JZ 3rd, et al. Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin induction therapy does not prolong survival after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNeil K, Glanville AR, Wahlers T, et al. Comparison of mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine for prevention of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in de novo lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2006;81:998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Real World Evidence: Maximize Benefits To Healthcare | eyeforpharma. http://social.eyeforpharma.com/market-access/real-world-evidence-maximize-benefits-healthcare. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- 44.Hachem RR, Edwards LB, Yusen RD, Chakinala MM, Alexander Patterson G, Trulock EP. The impact of induction on survival after lung transplantation: an analysis of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Registry. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emaminia A, Hennessy SA, Hranjec T, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome occurs earlier in the post-lung allocation score era. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1278–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yusen RD. Technology and outcomes assessment in lung transplantation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corris PA, Ryan VA, Small T, et al. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin therapy in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) post lung transplantation. Thorax. 2015;70:442–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kingah PL, Muma G, Soubani A. Azithromycin improves lung function in patients with post-lung transplant bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:906–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang W, Zilov A, Soewondo P, Bech OM, Sekkal F, Home PD. Observational studies: going beyond the boundaries of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88 Suppl 1:S3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Using Real-World Data for Outcomes Research and Comparative Effectiveness Studies. Research & Development https://www.rdmag.com/article/2014/11/using-real-world-data-outcomes-research-and-comparative-effectiveness-studies. Published November 4, 2014. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- 51.Mulligan MJ, Sanchez PG, Evans CF, et al. The use of extended criteria donors decreases one-year survival in high-risk lung recipients: A review of the United Network of Organ Sharing Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:891–898.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ehrsam JP, Benden C, Seifert B, et al. Lung transplantation in the elderly: Influence of age, comorbidities, underlying disease, and extended criteria donor lungs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154: 2135–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wise RA, Kowey PR, Austen G, et al. Discordance in investigator-reported and adjudicated sudden death in TIOSPIR. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Data (Charts and tables) - GODT. http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-charts-and-tables/. Accessed February 19, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.