Abstract

Rice bran albumin (RBAlb), which shows higher tyrosinase inhibitory activity than other protein fractions, was hydrolyzed with papain to improve the bioactivity. The obtained RBAlb hydrolysate (RBAlbH) was separated into 11 peptide fractions by RP-HPLC. Tyrosinase inhibition and copper chelation activities decreased with increasing retention time of the peptide fractions. RBAlbH fraction 1, which exhibited the greatest activity, contained 13 peptides whose sequences were determined by using LC-MS/MS. Most of the peptide sequences contained features of previously reported tyrosinase inhibitory and metal chelating peptides, especially peptide SSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG. RBAlbH fraction 1 showed more effective tyrosinase inhibition (IC50=1.31 mg/mL) than citric acid (IC50=9.38 mg/mL), but it was less effective than ascorbic acid (IC50=0.03 mg/mL, P ≤ 0.05). It showed copper-chelating activity (IC50=0.62 mg/mL) stronger than that of EDTA (IC50=1.06 mg/mL, P ≤ 0.05). These results suggest that RBAlbH has potential as a natural tyrosinase inhibitor and copper chelator for application in the food and cosmetic industries.

Keywords: rice bran albumin, enzymatic hydrolysates, tyrosinase inhibition, copper chelation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1) is a binuclear copper enzyme belonging to the polyphenol oxidases (PPO) family, which is widely distributed among plants, animals, and microorganisms. It catalyzes two different reactions in the presence of oxygen: the hydroxylation of monophenols to o-diphenols and the subsequent oxidation of o-diphenols to the corresponding o-quinones. These o-quinones are unstable and can undergo polymerization to form undesirable brown pigments called melanins.1–5 Tyrosinase is responsible for enzymatic browning in many vegetables and fruits during preparation process and long-term storage, leading to nutritional and economic loss.1,2,6 In addition, tyrosinase is involved in some hyperpigmentation disorders of the skin such as melasma and age spots. It may also be related to Parkinson’s disease and cancer.4,7 Thus, tyrosinase inhibition is of interest in the food, medicine and cosmetics fields.

Several potent substances have been applied for the purpose of tyrosinase inhibition. Ascorbic acid has been widely used as an antibrowning agent;3,8 however, its browning inhibitory effect is only temporary because of its rapid consumption during redox processes.2,9 Hydroquinone, kojic acid, and sulfite are effective compounds that have been used to inhibit tyrosinase. Hydroquinone and kojic acid are used as a skin-whitening agents to reduce melanin production, whereas sulfiting agents are used as enzymatic-browning inhibitors in many fruits and vegetable products. However, these compounds have adverse effects on human health.4,10 Moreover, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has prohibited the use of sulfite in most fresh fruits and vegetables.11 In addition, many consumers prefer to use natural substances as opposed to synthetic alternatives. Therefore, various tyrosinase inhibitors from natural sources have been widely investigated.

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the world’s most important food crops with a production of about 740 million metric tons,12 resulting in commensurately huge amounts of rice bran as a primary co-product derived from the outer layers of rice caryopsis. Rice bran comprises about 5–8% of paddy-rice weight and is removed during the milling process. It is mostly used as raw material in rice bran oil industry or as animal feed. However, rice bran is an excellent source of phytochemicals, vitamins, minerals, dietary fibers, and unsaturated fats as well as high quality proteins.13,14 Rice bran contains about 10–15% proteins.13 Rice-bran protein is hypoallergenic and it also shows anticancer- and antioxidant properties.13,15 Thus, rice bran protein has been extensively explored as a potential source of alternative ingredients in food and nutraceutical industries.

Several researchers have reported the tyrosinase-inhibitory effect and copper-chelating activity of proteins, protein hydrolysates, and peptides from natural sources such as rice bran,2,16 silk,17 sunflower,18 zein,19 chickpea,20,21 cowpea,22 and red seaweed.23 Some synthetic short peptides appear to show inhibitory activity against tyrosinase.4,7,24 Some oligopeptides25,26 and squid collagen hydrolysate27 that showed tyrosinase-inhibitory effects have been suggested as cosmetic agents. Bioactive peptides are small protein fragments that have biological activity after they are released from proteins by hydrolytic treatment.20,23 Hydrolytic cleavage involves the unfolding of native protein molecules; active moieties become more exposed or they are newly formed by hydrolysis. Protein hydrolysates from zein,19 casein, 28 and rice-starch by-product29 have been found to possess tyrosinase-inhibitory or copper- chelating activity greater than that of the protein they originate from. Papain is a commercial enzyme that has been used for the production bioactive peptides. Liu et al.30 reported that Camellia oleifera seed-cake papain hydrolysate exhibited excellent antioxidant activities and copper-chelating activity. Moreover, hydrolysates of casein31 and palm kernel cake protein32 produced by papain digestion demonstrated strong antioxidative activities and metal-chelating activity. Moreover, there have been some reports that the hydrolysates of rice-bran-protein fractions33 and brown-rice-protein fractions34 exhibit antioxidant activities. Wattanasiritham et al.15 isolated and identified the antioxidative peptides from hydrolyzed rice bran albumin. However, there is limited information about the tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities of rice-bran-protein fraction papain hydrolysates and their peptide structures. Therefore, the peptides in hydrolyzed rice-bran-albumin fractions were separated. The tyrosinase-inhibitory effect and copper-chelating activity of these hydrolyzed rice-bran-albumin fractions were investigated and the peptide sequences identified by mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The potential for controlling of tyrosinase varies with the source of rice cultivars and the tyrosinase source; thus, fresh rice bran from Khao Dawk Mali 105 (KDML 105) rice (Oryza sativa L.), the most popular Thai aromatic-rice variety and the variety that exhibited the highest PPO-inhibitory efficiency among commercially consumed rice varieties from our previous study, were selected for this study. KDML 105 was purchased from Surin Taveepol Rice Mill, Surin, Thailand. Tyrosinase from mushroom (EC 1.14.18.1) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sodium potassium tartrate, bovine serum albumin, papain, trifluoroacetic acid, 3,4-Dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (L-DOPA), and pyrocatechol violet were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Copper sulfate was purchased from Mallinckrodt Chemical (Paris, KY, USA). Potassium iodide was purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Acetonitrile was purchased from VWR Analytical (Radnor, PA, USA).

Preparation of Rice-Bran-Protein Fractions.

Full-fat rice bran was initially screened by being passed through a 50-mesh sieve and then defatted with three volumes of hexane according to the procedures of Kubglomsong and Theerakulkait.2 The obtained defatted rice bran was packed in an aluminum-foil bag and kept frozen at −20 ºC.

Rice-bran-protein fractions were prepared by the modified method of Agboola et al.35 with some modifications. The defatted rice bran was first extracted with distilled water (DW) in a 1:5 (w/v) ratio of rice bran to DW, using an overhead stirrer at 500 rpm for 60 min. After centrifugation (10 000g, 30 min) at 25 ºC, the supernatant was collected to obtain the albumin fraction. The residue from this step was similarly extracted with 5% NaCl, 0.1 M NaOH, and 70% ethanol to obtain globulin, glutelin, and prolamin fraction, respectively. The supernatant from each fraction was filtered through nylon cloth (100 mesh), and the pH was adjusted with 1.0 N HCl to 4.1, 4.3, 4.8, and 5.0. The rice–bran-protein fractions albumin (RBAlb), globulin (RBGlo), glutelin (RBGlu), and prolamin (RBPro) were obtained after centrifugation.

Rice-bran-protein fractions were dispersed in DW and adjusted to pH 7 with 1.0 N NaOH, then centrifuged (10 000g, 30 min) at 25 ºC. The supernatants were dialyzed using dialysis tubing with a molecular-weight cut-off of 6,000 Da against DW at 4 ºC overnight and then centrifuged under the same conditions. The protein content, molecular weight, and tyrosinase-inhibition of rice-bran-protein fractions were determined as described below.

Determination of Protein Content.

Biuret reagent was prepared by dissolving 2.5 g of potassium iodide, 4.5 g of sodium potassium tartrate, and 1.5 g of copper sulfate (CuSO4.5H2O) in 200 mL of 0.2 M NaOH and then adjusting the final volume to 500 mL with DW (a modified method of Chanput et al.).33 Sample (30 μL) was pipetted into a 96-well plate and mixed with 150 μL of biuret reagent. The absorbance at 540 nm was read against the reagent blank after a 30 min incubation. Protein concentration was quantified using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard with a concentration ranging from 1 to 10 mg/mL.

Determination of the Molecular Weight of Protein by Gel Electrophoresis.

The molecular weight of the rice-bran-protein fractions were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to the modified procedure of Tang et al.36 with 12 and 4% (w/v) acrylamide separating gel and stacking gel, respectively. The samples at protein concentration of 4 μg/mL were mixed with sample buffer containing 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% (w/v) SDS, glycerol, 1% (w/v) bromophenol blue, and 2-mercaptoethanol then heated for 5 min in boiling water. After cooling to room temperature, 10 μL aliquots of the sample solutions were loaded into the gel wells for electrophoresis with an electrode buffer (pH 8.3) consisting of 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 1.44% (w/v) glycine, and 0.3% (w/v) Tris base. SDS-PAGE was run using a Mini-Protean® Tetra Vertical Electrophoresis Cell and a model 3000XI power supply (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). For protein visualization, the gel was stained by immersion in a solution consisting of 0.1% (w/v) Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in a mixture of 40% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid. The gel was destained in a solution consisting of 40% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid. PageRuler™ Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) was used as the standard marker with a molecular-weight range of 10–250 kDa.

Determination of Tyrosinase Inhibition.

Tyrosinase-inhibitory activity was determined using a 96-well plate (a modified method of Masuda et al.).6 Tyrosinase was prepared at 100 U/mL in 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The wells were assigned the following mixtures: control (without sample): 120 μL of 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), and 40 μL of tyrosinase; blank (without sample and without tyrosinase); 160 μL of the buffer; sample: 80 μL of the buffer, 40 μL of tyrosinase, and 40 μL of the sample; blank sample (without tyrosinase): 120 μL of the buffer and 40 μL of the sample solutions. The reaction contents of each well were mixed with a microplate mixer and incubated at room temperature for 10 min; then, 40 μL of 2.5 mM L-DOPA prepared in the same buffer was added, and the solution was incubated at room temperature for 2 min. The absorbance (A) at 475 nm was measured with a microplate reader (SpectraMax 190 Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Percentage tyrosinase-inhibitory activity was calculated as:

Determination of Copper-Chelating Activity.

The copper-chelating activities of RBAlbH fractions were measured according to the modified method of Carrasco-Castilla et al.37 RBAlbH fractions (10 μL) were mixed with 280 μL of 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0), 6 μL of 4 mM pyrocatechol violet prepared in the same buffer, and 10 μL of 1 μg/μL CuSO4.5H2O. The disappearance of the blue color was observed by measuring the absorbance at 632 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax 190 Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Water was used as a control instead of a sample. Percentage copper-chelating activity was calculated from absorbance (A) at 632 nm as follows:

Effect of Rice-Bran-Protein Fractions on Tyrosinase Inhibition.

Rice-bran-protein fractions RBAlb, RBGlo, RBGlu, and RBPro were adjusted to protein concentration of 2 mg/mL and investigated for mushroom-tyrosinase inhibition. The rice-bran-protein fraction that showed the highest tyrosinase-inhibitory activity (RBAlb) was selected for further study.

Effect of RBAlb Concentration on Tyrosinase Inhibition.

The RBAlb fraction was prepared at protein concentrations of 1–10 mg/mL, and then tyrosinase-inhibition was investigated. The protein concentration of RBAlb that showed the highest tyrosinase-inhibition (8 mg/mL) was selected for hydrolysis and the isolation and identification of tyrosinase-inhibitory and copper-chelating peptides.

Preparation of Rice-Bran-Albumin Hydrolysate (RBAlbH).

RBAlb at a protein concentration of 8 mg/mL was hydrolyzed with papain at conditions optimized from our preliminary studies that led to the highest tyrosinase-inhibition at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:100 (w/w) at 37 ºC. The pH was maintained at 8.0 for the duration of hydrolysis time with 1.0 N NaOH. Hydrolysis was carried out for 30 min, then terminated by immersing the incubation container in boiling water for 5 min and cooling quickly with an ice bath. The obtained RBAlbH was freeze-dried and kept in aluminum-foil bags at −20 ºC for further study.

Isolation of Peptides from RBAlbH.

The lyophilized RBAlbH was mixed with Milli-Q water (100 mg/mL) and centrifuged at 13 000g at 25 ºC for 5 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon filter (Thermo Scientific, Rockwood, TN, USA), and then, 100 μL of the sample was fractionated by reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a Discovery® BIO Wide Pore C18 HPLC Column (5 μm, 25 cm × 10 mm i.d.) (Supelco, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with a Discovery® BIO Wide Pore C18 Supelguard™ Cartridge (10 μm, 1 cm × 10 mm i.d.) (Supelco). The HPLC system (Waters Delta 600, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) consisted of a vacuum degasser, a quaternary solvent pump, a Waters 717 Plus autosampler, a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector and a computer with Empower software. Separation was performed using 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water as eluent A and acetonitrile (ACN) as eluent B with the flow rate at 4.0 mL/min. The solvent gradient was kept at 0% B for 2.5 min, then changed from 0 to 30% B over 20 min, then changed from 30 to 100% B over 7.5 min, and then kept at 100% B for 6 min. Fractions eluting from the column were manually collected by observation of the chromatogram monitored at 215 and 280 nm. RBAlbH fractions were concentrated at 40 ºC under vacuum using a rotary evaporator to remove most of the acetonitrile, and then the concentrate was freeze-dried. Each RBAlbH fraction was reconstituted with water and adjusted to the same protein concentration of 1 mg/mL for determination of tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activity.

Identification of Amino Acid Sequences of RBAlbH Fractions by LC-MS/MS.

Each RBAlbH fraction (fractions 1–11, 1 μL) isolated by RP-HPLC was injected into a nanoLC-MS system (an Orbitrap Fusion™ Lumos mass spectrometer) with a Nano ESI source (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) coupled with a Waters nanoAcquity™ UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA)). Peptides were loaded on a 2G nanoAcquity UPLC®Trap column (180 μm × 20 mm, 5 μm) for 5 min with a solvent of 0.1% formic acid in 3% ACN at a flow rate of 5 μL/min. They were then separated by an Acquity UPLC® Peptide BEH C18 column (100 μm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) following a 120 min gradient at a flow rate of 500 nL/min consisting of mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile), where B was increased from 3 to10% over 3 min, from 10 to 30% over 102 min, from 30 to 90% over 3 min; held at 90% for 4 min; decreased from 90 to 3% over 1 min; and held at 3% for 7 min. The nanoLC eluate was directly electrosprayed into the mass spectrometer in positive-ion-mode. The spray voltage was 2400 V , and the ion-transfer-tube temperature was 300 ºC. Full MS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap at resolution settings of 120,000 at m/z 200 with a scan range from 400 to 1500, and the automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to 4.0 × 105. Under top-speed data-dependent mode, the most intense parent-ion peaks with charge-state range of 2–7 were selected for fragmentation by collision-induced dissociation (CID) with a normalized collision energy of 35%. MS/MS spectra were acquired in the ion trap with the exclusion window set at 1.6 Da and AGC of 104.

All raw data files were analyzed with Thermo Scientific™ Proteome Discoverer™ 2.1 software and searched using Sequest HT against Uniprot Oryza sativa protein database including the Papain enzyme sequence. The overall false-discovery rate (FDR) for peptides was less than 1% and peptide sequences were allowed a maximum of two missed cleavages. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine and oxidation of methionine were specified as a static modification and dynamic modification, respectively. Mass tolerances were set at ±10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.6 Da for fragments.

Statistical Analysis.

The experiments were performed with three replications. The data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance. Duncan’s multiple-range tests were applied for significant differences between treatments (P ≤ 0.05).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of Rice-Bran-Protein Fractions on Tyrosinase Inhibition.

The tyrosinase-inhibition percentages of rice-bran-protein fractions are shown in Figure 1. It was found that the tyrosinase-inhibitory effect of RBAlb was higher than those of RBGlu, RBGlo, and RBPro (P ≤ 0.05). Therefore, RBAlb was selected for further study. The different amino acid profiles of rice-bran-protein fractions might establish the different tyrosinase inhibition levels. Padhye and Salunkhe38 found that rice albumin contained higher amounts of uncharged, polar amino acids than other fractions, whereas the prolamin fraction had the lowest. Schurink et al.24 reported that peptides containing polar, uncharged amino acid residues, such as serine and cysteine, are good tyrosinase inhibitors. This might be related to the tyrosinase-inhibition of RBAlb. In addition, Wang et al.39 reported that the rice-bran-glutelin fraction contained high amounts of sulfur-containing amino acids, such as cysteine, which have been reported as inhibiting tyrosinase activity.

Figure 1.

Percent tyrosinase-inhibition of rice-bran-protein fractions albumin (RBAlb), globulin (RBGlo), glutelin (RBGlu), and prolamin (RBPro). Means with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

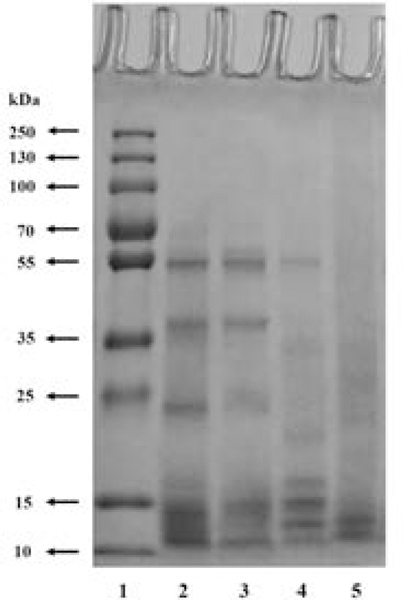

Molecular weights of rice-bran-protein fractions were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Figure 2). It was found that the molecular weights of RBAlb, RBGlo and RBGlu were in the range of 10–60 kDa, whereas those of RBPro were in the range of 10–15 kDa. These results are in agreement with those of Chanput et al.,33 who reported similar molecular weights for the same fractions. In addition, Padhye and Salunkhe38 found that the molecular weights of rice albumin, globulin, glutelin, and prolamin were in the ranges of 7–135, 13–60, 8–29, and 7–13 kDa, respectively. Rice-bran proteins reported by Tang et al.36 were in the range of 6.5–66.2 kDa.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE patterns of the molecular-weight marker (lane 1) and the rice-bran-albumin (lane 2), globulin (lane 3), glutelin (lane 4), and prolamin fraction (lane 5)

Effect of RBAlb Concentration on Tyrosinase Inhibition.

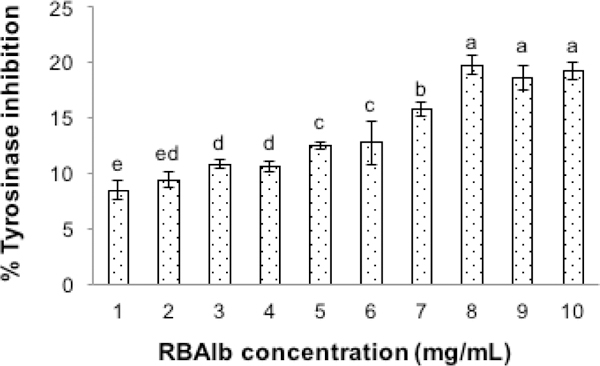

Tyrosinase-inhibition percentages of RBAlb at different protein concentrations are shown in Figure 3. Increasing RBAlb protein concentration from 1 to 8 mg/mL gradually increased tyrosinase-inhibitory effect (P ≤ 0.05); however, the inhibitory effect of RBAlb did not increase at protein concentration of 9 and 10 mg/mL (P > 0.05). This result reveals that RBAlb showed tyrosinase-inhibition in a dose-dependent manner until saturation occurred at 9 mg/mL. This result was in line with the work of Lee et al.40 work who found that the tyrosinase-inhibitory ability of the synthetic hexapeptide (SFKLRY-NH2) increased with the increasing of concentrations before a plateau was reached.

Figure 3.

Percent tyrosinase-inhibition of the rice-bran-albumin fraction (RBAlb) at different protein concentrations. Means with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Tyrosinase-Inhibition and Copper-chelating Activity of Peptide Fractions from RBAlbH.

An HPLC chromatogram showing the 11 peptide fractions from RBAlbH is presented in Figure 4. The tyrosinase-inhibitory and copper-chelating activities of each fraction are shown in Figure 5a,b, respectively. For both tyrosinase-inhibition (Figure 5a) and copper-chelating activities (Figure 5b), we found that the first eluted fraction had the highest activities. The tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities of the fractions decreased with elution time and showed the lowest activity in fraction 11. The earlier-eluting fractions contained peptides that exhibited greater tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities than the later-eluting fractions. In addition, the earlier-eluting fractions were rich in serine, and erine is ahydrophilic residue. These results are similar to those of Megías et al.,18,41 who reported that RP-HPLC fractions of chickpea and sunflower-protein hydrolysates that eluted first exhibited the greatest copper-chelating activity. Tyrosinase is an enzyme that contains a binuclear copper active site for catalyzing the oxidation reaction. These two copper ions are essential for the enzyme activities and are directly involved in the monophenolase and diphenolase reactions of tyrosinase.4,5,10 Therefore, the chelation of copper ions at the active site of tyrosinase could retard or interrupt the enzyme activity.5,17 Kahn28 demonstrated that proteins, peptides, and amino acids could reduce tyrosinase activity by chelating the essential copper at the active site. In addition, several researchers have reported the relation between tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities in their research on squid- skin-collagen hydrolysate,27 whey-protein-isolates,42 proteins, protein hydrolysates, and amino acids from milk,28 hydroxypyridinone derivatives,5 and collagen peptide from jellyfish.43 Moreover, molecular docking was performed by some researchers to understand the interaction between inhibitor and binding site of tyrosinase. It was found that hydroxypyridinone derivatives5 and indole-containing octapeptides44 chelated with copper at the enzyme active site, thereby influencing the tyrosinase inhibition. Therefore, we supposed that the tyrosinase-inhibitory mechanism of RBAlbH likely involves copper-chelating activity.

Figure 4.

HPLC profile of RBAlbH separated by a Supelco C18 HPLC Column (5 μm, 25 cm × 10 mm i.d.) monitored at 280 (a) and 215 (b) nm. Elution was performed with the gradient of acetonitrile (0–100%) and water containing 0.1% TFA. Numbers (1–11) represent the fractions collected.

Figure 5.

(a) Percent tyrosinase-inhibition and (b) copper-chelating activity of RBAlbH fractions isolated by RP-HPLC at 1 mg/mL protein concentration. Means with different letters are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Table 1 shows IC50 values for RBAlbH fraction 1, commercial tyrosinase inhibitors (ascorbic acid and citric acid)3,8 and a known strong metal-ion chelator (EDTA).17 RBAlbH fraction 1 effectively inhibited tyrosinase activity with IC50 of 1.31 mg/mL. Its inhibitory efficiency was greater than that of citric acid, which showed IC50 of 9.38 mg/mL (P ≤ 0.05); however, its inhibitory efficiency was lower than that of ascorbic acid, which showed an IC50 of 0.03 mg/mL (P ≤ 0.05). In addition, RBAlbH fraction 1 showed copper-chelating activity with an IC50 of 0.62 mg/mL, whereas EDTA had an IC50 of 1.06 mg/mL. This result suggested that RBAlbH exhibited a stronger copper-chelating activity than EDTA on a mass basis (P ≤ 0.05). In addition, RBAlbH fraction 1 exhibited a greater tyrosinase-inhibition than sericin hydrolysate, reported by Wu et al.17 to have an IC50 of 8.71 mg/mL. The copper-chelating activity of RBAlbH fraction 1 was stronger than those of zein hydrolysate19 and whey-protein isolate,42 which showed IC50 values of about 16 and 6 mg/mL, respectively. However, RBAlbH fraction 1 showed less inhibitory activity than collagen peptide from jellyfish,43 which showed tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activity IC50 values of 78.2 and 88.7 μg/mL, respectively.

Table 1.

IC50 values for Tyrosinase-inhibition and Copper-chelating Activities of RBAlbH Fraction 1 and Commercial Substances

| IC50 (mg/mL) (mean±SD) a, b | ||

|---|---|---|

| tyrosinase inhibition | copper chelating | |

| RBAlbH fraction 1 | 1.31 ± 0.05B | 0.62 ± 0.01B |

| citric acid | 9.38 ± 0.06A | - |

| ascorbic acid | 0.03 ± 0.00C | - |

| EDTA | - | 1.06 ± 0.08A |

IC50 is the concentration that causes 50% reduction of tyrosinase activity or copper-chelating activity.

- not determined

Means ± SD with different letters in the same column are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Identification of Amino Acid Sequences of RBAlbH Fractions by LC-MS/MS.

The peptides in the RBAlbH fractions were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Thirteen peptides from RBAlbH fraction 1, the most active fraction, were identified and are shown in Table 2. These peptides range from 14 to 50 residues and have molecular weights ranging from 1327 to 4819 Da. Peptide size has been reported to associate with biological activities. Zhuang et al.45 found that the peptides from corn-gluten meal at molecular weight <10 kDa showed good copper-chelating activity. Wu et al.17 observed that the molecular weights of the main fraction from sericin hydrolysate, which showed tyrosinase inhibition, had a mass distribution ranging from 250 to 4000 Da. Serine, glycine, alanine, and glutamic acid were detected in high amounts in the identified peptide sequences of RBAlbH fraction 1. Valine, leucine and tyrosine were found in intermediate amounts. These amino acids have been reported to contribute to tyrosinase-inhibition and metal-chelating activity.1,17,19,22,23,24,46

Table 2.

Amino Acid Sequences of Peptides from RBAlbH Fraction 1 Identified by LC-MS/MS

| No. | peptide sequence | molecular weight (Da) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | DASLTRLDLAGANGTDLAYGISLTVAV | 2677 |

| 2 | PRCSASSTTPRSTTSAAWRAPSAPTSSTS | 2966 |

| 3 | QSSKQRRDNGIFFVPQRPYMVLGTLRQQLLYPTW | 4123 |

| 4 | DVLEEGNSGDPPLFVSDVLHGAAIEVNEEGTEVAAATVVIMKGRA | 4606 |

| 5 | QGWSSSSSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG | 2725 |

| 6 | GWSSSSSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG | 2597 |

| 7 | SSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG | 2093 |

| 8 | VELEEKGEGAAMTE | 1509 |

| 9 | AAAVAMAAAVAAGEGGAANYLVFVDPPPSGVVCTAYQLSILAAALGSEEK | 4819 |

| 10 | SSHAAARRLRRSSSP | 1639 |

| 11 | GEPVAAEERDDGVGVAGE | 1757 |

| 12 | SSSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG | 2180 |

| 13 | LSLIGAVGGIGGSIL | 1327 |

The presence of certain amino acids appears to be related to the tyrosinase-inhibitory and metal-chelating activities of the peptides. Percent frequency of individual amino acids in the identified peptides of RBAlbH RP-HPLC fractions 1–11 were calculated on the base of total amino acid residues in each fraction and are shown in Table 3. It was found that the first-eluting fraction contained the greatest serine portion in the peptide sequences; there was similar serine content in fraction 2, and it decreased gradually in the later- eluting fractions. This result tends to be in agreement with tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities reported in Figure 5a,b. Thus, serine is the amino acid that may be responsible for the pattern of activities observed in fraction 1 through 11 that are shown in Figure 5a,b. From Table 2, we found that almost all peptide sequences in RBAlbH fraction 1 shared in common the presence of a serine (peptide sequences 1–7, 9, 10, 12 and 13), especially peptide sequences 2, 5, 6, 7, 10, and 12, which contained several serines (9, 8, 8, 5, 5, and 6 serines, respectively) and are of considerable interest. Moreover, percent frequencies of some features in the identified peptides of RBAlbH RP-HPLC fractions 1–11 were calculated on the base of total amino acid residues in each fraction and are shown in Table 4. We found that multiple adjacent serine residues (i.e., SS, SSS, or SSSSS) were generally in higher frequency in peptide sequences from the earlier-eluting RBAlbH fractions than the later-eluting fractions. This suggested that SS, SSS or SSSSS content could be related with the pattern of activities observed in RBAlbH fractions (Figure 5a,b). Peptide sequences 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10 and 12 from RBAlbH fraction 1 contained multiple adjacent serine residues and are of interest. Ochiai et al.10 reported that adjacent amino acid residues may affecttyrosinase-inhibitory activity. Our results are consistent with several studies that reported that serine could be a residue involved in the active peptides that exhibited tyrosinase-inhibition or copper-chelating activity from the hydrolysates of sericin,17 zein,19 chickpea,20 cowpea22 and red seaweed.23 Schurink et al.24 reported that peptides containing polar, uncharged amino acids, such as serine, effectively inhibit tyrosinase activity. The tyrosinase-inhibitory effect observed for serine-containing peptides may be because of their capacity to bind copper ions, which are needed for tyrosinase activity. The mechanism of copper binding by serine residues was reported by Mandal et al.47 who found that serine binds to copper ions through the oxygen and nitrogen atoms of its carboxylate and amino groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Individual Amino Acid Frequencies (%)a in the Peptides Identified by LC-MS/MS of RBAlbH RP-HPLC Fractions 1–11

| amino acid | f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | f6 | f7 | f8 | f9 | f10 | f11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G (Gly) | 15.34 | 11.83 | 15.63 | 12.25 | 27.21 | 19.50 | 17.89 | 16.93 | 10.78 | 10.54 | 12.93 |

| A (Ala) | 11.80 | 9.68 | 18.75 | 11.76 | 14.91 | 16.62 | 14.22 | 13.29 | 13.21 | 11.39 | 14.83 |

| V (Val) | 6.49 | 9.68 | 12.50 | 4.90 | 2.00 | 3.38 | 4.12 | 5.26 | 6.93 | 6.76 | 8.48 |

| L (Leu) | 6.19 | 4.30 | 4.69 | 9.31 | 3.23 | 0.90 | 1.28 | 2.82 | 6.70 | 8.00 | 6.76 |

| I (Ile) | 2.36 | 1.08 | 3.13 | 6.86 | 1.31 | 1.27 | 1.68 | 2.68 | 3.55 | 3.55 | 3.65 |

| M (Met) | 1.18 | 4.30 | 6.25 | 2.45 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 1.27 | 1.59 | 1.45 | 1.58 | 1.84 |

| F (Phe) | 1.18 | 2.15 | 4.69 | 2.45 | 1.54 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.90 | 2.07 | 4.21 | 3.41 |

| W (Trp) | 1.18 | 1.08 | 1.56 | 2.94 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 0.52 |

| P (Pro) | 4.13 | 4.30 | 3.13 | 5.39 | 1.92 | 6.27 | 6.21 | 5.51 | 4.60 | 4.25 | 3.01 |

| S (Ser) | 15.34 | 13.98 | 6.25 | 10.78 | 8.92 | 9.08 | 10.74 | 8.16 | 6.95 | 7.84 | 8.02 |

| T (Thr) | 4.42 | 0.00 | 4.69 | 2.45 | 10.30 | 8.02 | 5.42 | 5.01 | 5.33 | 5.33 | 5.62 |

| C (Cys) | 0.59 | 3.23 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Y (Tyr) | 6.19 | 6.45 | 3.13 | 0.98 | 0.69 | 3.96 | 5.37 | 3.92 | 2.43 | 3.40 | 2.58 |

| N (Asn) | 1.47 | 1.08 | 3.13 | 4.41 | 2.23 | 1.63 | 1.96 | 2.66 | 3.98 | 3.17 | 3.01 |

| Q (Gln) | 3.24 | 7.53 | 4.69 | 3.92 | 3.46 | 5.53 | 5.07 | 5.37 | 4.60 | 3.71 | 3.56 |

| D (Asp) | 2.95 | 1.08 | 3.13 | 4.90 | 7.07 | 6.29 | 6.67 | 7.51 | 7.53 | 7.76 | 7.16 |

| E (Glu) | 10.03 | 11.83 | 3.13 | 2.45 | 5.07 | 10.65 | 12.04 | 11.18 | 11.01 | 10.54 | 9.34 |

| K (Lys) | 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 1.96 | 4.07 | 2.56 | 2.62 | 3.51 | 4.52 | 2.94 | 2.30 |

| R (Arg) | 4.13 | 4.30 | 1.56 | 7.35 | 2.84 | 1.54 | 1.62 | 2.55 | 2.32 | 2.90 | 2.09 |

| H (His) | 0.59 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 1.31 | 1.28 | 1.07 | 0.77 | 1.20 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

Percent frequency was calculated on the basis of total amino acid residue occurrence in each fraction.

Table 4.

Frequencies (%)a of Some Features in the Peptides Identified by LC-MS/MS of RBAlbH RP-HPLC Fractions 1–11

| features | f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | f6 | f7 | f8 | f9 | f10 | f11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | 1.47 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 1.39 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.74 |

| SSS | 1.77 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| SSSSS | 0.59 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SSSE | 1.47 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.93 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| SSSSSE | 0.59 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Combination of R-L | 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| SSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG | 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

Percent frequency was calculated on the basis of total amino acid residue occurrence in each fraction.

As shown in Table 3, sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine and methionine) in RBAlbH fractions tend to correlate with tyrosinase-inhibitory and copper-chelating activities (Figure 5a,b). Thus, the inhibitory activities could be partially due to cysteine or methionine contents in peptide sequences. Peptide sequences 2–4, 8, and 9 from RBAlbH fraction 1 contained sulfur-containing amino acids. Cysteine has been reported to inhibit tyrosinase activity by reacting with o-quinone intermediates to give stable, colorless cysteine-quinone adducts, reducing o-quinones to their original polyphenol precursors and preventing the formation of polymeric browning products. Additionally or alternatively, peptides can inhibit tyrosinase by competing with tyrosinase for binding of catalytically active transition copper ions.1,8 Wu et al.48 reported that cysteine-containing peptides could chelate with copper ions with their thiol groups. Ali et al.1 reported that cysteine and methionine effectively inhibited enzymatic browning in potato.

Tryptophan was found generally in higher portion in the earlier-eluting RBAlbH fractions than in the later-eluting fractions (Table 3) and is thus in agreement with the pattern of activities observed in RBAlbH fractions (Figure 5a,b). As shown in Table 2, peptide sequences 2, 3, 5, and 6 of RBAlbH fraction 1 contained tryptophan. Ubeid et al.44 reported that tryptophan-containing peptides showed tyrosinase-inhibitory activity, and that activity increased as the number of tryptophan residues in the peptide sequences increased. Baakdah and Tsopmo46 also found that peptides from hydrolyzed oat-bran protein contained tryptophan that was correlated with metal-chelating activity. The indole moiety of tryptophan has been found to contribute to tyrosinase-inhibition by interaction with copper ions and also with the imidazole group of histidines within tyrosinase’s active site.44

Arginine-containing peptides have also been connected with tyrosinase-inhibition or copper-chelating activity.4,18,20,21,22,23,41 In general, the arginine proportion in the earlier-eluting fractions was higher than that in the later-eluting fractions (Table 3) and thus was consistent with the tyrosinase-inhibitory and copper-chelating activities (Figure 5a,b). As shown in Table 2, peptide sequences 1–4, 10 and 11 of RBAlbH fraction 1 contained arginine, and peptide sequences 3 and 10 each had four arginine residues. Schurink et al.24 proposed that peptides containing one or more arginine residues usually exhibited effective tyrosinase binding activity. Zhuang et al.45 claimed that arginine residues favor binding to metal through their charged groups. Wu et al.48 also reported that copper ions bind with the guanidine group of arginine. Thus, arginine content might be responsible for some of the copper-chelating and tyrosinase-inhibitory ability.

Schurink et al.24 mentioned that peptides containing arginine in combination with leucine usually showed good tyrosinase-inhibitory activity. These combinations were found generally in higher frequency in peptide sequences from the earlier-eluting RBAlbH fractions than in those from the later-eluting fractions (Table 4), in general agreement with the pattern of activities observed in RBAlbH fractions (Figure 5a,b). When we considered the peptide sequences in the most active RBAlbH fraction (Table 2), we found that the arginine-leucine combination was found in peptide sequences 1, 3 and 10. Among these peptide sequences, peptide 10 contained two arginines that were adjacent to leucine (position 8–10, respectively). We also found that multiple adjacent serines next to glutamic acid in the peptide sequences (i.e., SSSE, SSSSSE, Table 4) correlated with tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities (Figure 5a,b). RBAlbH fractions 1 and 2 showed high contents of multiple adjacent serines next to glutamic acid, whereas the later-eluting fractions showed lower content. Furthermore, peptide sequences 5–7 and 12 from RBAlbH fraction 1 contained multiple adjacent serine residues next to glutamic acid.

RBAlbH fraction 1 contained several peptide sequences (5– 7 and 12) that had the same pattern of SSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG in their peptide sequences (Table 2). Moreover, this sequence showed high frequency in RBAlbH fraction 1 and 2, whereas the later-eluting fractions showed lower frequencies of this (Table 4). This peptide sequence may contribute to the potency of active RBAlbH fractions. It consists of well-known tyrosinase-inhibitory and metal chelating amino acids: five serine, four glutamic acid, four tyrosine, and six glycine residues. Serine, glutamic acid, and tyrosine have been reported to contribute to tyrosinase-inhibition and metal chelating activities.4,17,19,23,24,46 Moreover, Ali et al.1 reported that glycine has the potential to inhibit enzymatic browning in potato as well.

Several peptide features have been found to correlate with the patterns of tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities observed in RBAlbH RP-HPLC fractions, including the presence of certain amino acids and structural features. We found that many peptides from active fractions contained high proportions of serine, arginine, tryptophan, cysteine and methionine, and arginine in the combination with lysine; multiple adjacent serine residues, and serine next to glutamic acid. Several peptides from the most active RBAlbH fraction, fraction 1, contained more than one of these aforementioned features: peptides 2, 3, 5–7, 10 and 12 are of considerable interest and may be important for activities. Peptides 2 and 3 contained high amounts of serines, tryptophans, and arginines. They also contained cysteines and, methionines, and multiple adjacent of serine residues. Peptide 3 also contained the combination of arginine with leucine. Peptides 5–7 and 12 contained high amounts of serine, multiple adjacent serines, and serine next to glutamic acid. They also share in common the amino acid sequence SSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG. Additionally, peptides 5 and 6 also contained tryptophan in the sequences. Peptide 10, with a high portortion of serines and arginines as well as the multiple adjacent serines and the arginine-leucine combination, might contribute to the robust tyrosinase-inhibition and copper-chelating activities observed for this fraction. Several sequences obtained from RBAlbH fraction 1 contained interesting features, including peptide 2 (PRCSASSTTPRSTTSAAWRAPSAPTSSTS), peptide 3 (QSSKQRRDNGIFFVPQRPYMVLGTLRQQLLYPTW), peptide 5 (QGWSSSSSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG), peptide 6 (GWSSSSSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG), peptide 7 (SSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG), peptide 10 (SSHAAARRLRRSSSP), and peptide 12 (SSSEYYGGEGSSSEQGYYGEG).

In conclusion, RBAlb showed greater dose-dependent mushroom- tyrosinase-inhibitory effect than the other fractions. RBAlb hydrolyzed by papain is an effective enzymatic-browning inhibitor because of its strong inhibition of tyrosinase activity and its copper-chelating activity. The most active RBAlbH fraction exhibited more effective tyrosinase-inhibition than citric acid and showed copper-chelating activity stronger than that of EDTA. Several of the peptides detected contained characteristics found in well-known tyrosinase-inhibitory and metal chelating peptides, including specific amino acid residues, especially serine, sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine and methionine), tryptophan, and arginine; multiple adjacent serine residues; and serine next to glutamic acid. Thus, rice-bran-albumin papain hydrolysate has potential for use as a natural tyrosinase inhibitor and copper chelator in the foods, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude and appreciation to the Linus Pauling Institute and the Mass Spectrometry Center at Oregon State University for assistance with peptide isolation and characterization.

FUNDING SOURCE

This study was financially supported by the Thailand Research Fund through the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (Grant No. PHD/0050/2551 to S. Kubglomsong and C. Theerakulkait). The Orbitrap mass spectrometer was purchased with funding from the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. S10OD020111).

REFERENCES

- (1).Ali HM; El-Gizawy AM; El-Bassiouny REI; Saleh MA The role of various amino acids in enzymatic browning process in potato tubers, and identifying the browning products. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kubglomsong S; Theerakulkait C Effect of rice-bran-protein extract on enzymatic browning inhibition in potato puree. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014a, 49, 551–557. [Google Scholar]

- (3).McEvily AJ; Iyengar R; Otwell WS Inhibition of enzymatic browning in foods and beverages. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1992, 32, 253–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ubeid AA; Zhao L; Wang Y; Hantash BM Short-sequence oligopeptides with inhibitory activity against mushroom and human tyrosinase. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2242–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhao D-Y; Zhang M-X; Dong X-W; Hu Y-Z; Dai X-Y; Wei X; Hider RC; Zhang J-C; Zhou T Design and synthesis of novel hydroxypyridinone derivatives as potential tyrosinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 3103–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Masuda T; Odaka Y; Ogawa N; Nakamoto K; Kuninaga H Identification of Geranic acid, a tyrosinase inhibitor in lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Tseng T-S; Tsai K-C; Chen W-C; Wang Y-T; Lee Y-C; Lu C-K; Don M-J; Chang C-Y; Lee C-H; Lin H-H; Hsu H-J; Hsiao N-W Discovery of potent cysteine-containing dipeptide inhibitors against tyrosinase: a comprehensive investigation of 20 × 20 dipeptides in inhibiting dopachrome formation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 27, 6181–6188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ali HM; El-Gizawy AM; El-Bassiouny REI; Saleh MA Browning inhibition mechanisms by cysteine, ascorbic acid and citric acid, and identifying PPO-catechol-cysteine reaction products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 3651–3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rojas-Graü MA; Soliva-Fortuny R; Martín-Belloso O Effect of natural antibrowning agents on color and related enzymes in fresh-cut fuji apples as an alternative to the use of ascorbic acid. J. Food Sci. 2011, 73, S267–S272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ochiai A; Tanaka S; Imai Y; Yoshida H; Kanaoka T; Tanaka T; Taniguchi M New tyrosinase-inhibitory decapeptide: molecular insights into the role of tyrosine residues. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2016, 121, 607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Sulfiting agents; revocation of GRAS status for use on fruits and vegetables intended to be served or sold raw to consumers. Fed. Regist. 1986, 51, 25021–25026. [Google Scholar]

- (12).FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). FAOSTAT. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/(2018.02.05). [PubMed]

- (13).Friedman M Rice brans, rice bran oils, and rice hulls: composition, food and industrial uses, and bioactivities in humans, animals, and cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 10626–10641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Han S-W; Chee K-M; Cho S-J Nutritional quality of rice-bran-protein in comparison to animal and vegetable protein. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 766–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wattanasiritham L; Theerakulkait C; Wickramasekara S; Maier CS; Stevens JF Isolation and identification of antioxidant peptides from enzymatically hydrolyzed rice bran protein. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kubglomsong S; Theerakulkait C Effect of rice-bran-protein extract on enzymatic browning inhibition in vegetable and fruit puree. Kasetsart J.: Nat. Sci. 2014b, 48, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wu J-H; Wang Z; Xu S-Y Enzymatic production of bioactive peptides from sericin recovered from silk industry wastewater. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 480–487. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Megías C; Pedroche J; Yust MM; Girón-Calle J; Alaiz M; Millán F; Vioque J Affinity purification of copper-chelating peptides from sunflower protein hydrolysates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007a, 55, 6509–6514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zhu L; Chen J; Tang X; Xiong YL Reducing, radical scavenging, and chelation properties of in vitro digests of alcalase-treated zein hydrolysate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2714–2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Torres-Fuentes C; Alaiz M; Vioque J Affinity purification and characterisation of chelating peptides from chickpea protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Torres-Fuentes C; Alaiz M; Vioque J Chickpea chelating peptides inhibit copper-mediated lipid peroxidation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 3181–3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Segura-Campos M; Ruiz-Ruiz J; Chel-Guerrero L; Betancur-Ancona D Antioxidant activity of Vigna unguiculata L. walp and hard-to-cook Phaseolus vulgaris L. protein hydrolysates. CyTA-J. Food. 2013, 11, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cian RE; Garzón AG; Ancona DB; Guerrero LC; Drago SR Chelating properties of peptides from red seaweed Pyropia columbina and its effect on iron bio-accessibility. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2016, 71, 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Schurink M; van Berkel WJH; Wichers HJ; Boeriu CG Novel peptides with tyrosinase-inhibitory activity. Peptides. 2007, 28, 485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nie H; Liu L; Yang H; Guo H; Liu X; Tan Y; Wang W; Quan J; Zhu L A novel heptapeptide with tyrosinase-inhibitory activity identified from a phage display library. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 181, 219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lien C-Y; Chen C-Y; Lai S-T; Chan C-F Kinetics of mushroom tyrosinase and melanogenesis inhibition by N-Acetyl-pentapeptides. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, (409783), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Nakchum L; Kim SM Preparation of squid skin collagen hydrolysate as an antihyaluronidase, antityrosinase, and antioxidant agent. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 46, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kahn V Effect of proteins, protein hydrolyzates and amino acids on o-dihydroxyphenolase activity of polyphenol oxidase of mushroom, avocado, and banana. J. Food Sci. 1985, 50 (1), 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ferri M; Graen-Heedfeld J; Bretz K; Guillon F; Michelini E; Calabretta MM; Lamborghini M; Gruarin N; Roda A; Kraft A; Tassoni A Peptide fractions obtained from rice by-products by means of an environment-friendly process show In vitro health-related bioactivities. PLoS One. 2017, 12 (1): e0170954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Liu J; Li X; Xiang C; Liu L; Feng S; Ding C Functional properties of Camellia oleifera seed-cake protein and antioxidant activity of its enzymatic hydrolysate. J. Chin. Cereals Oils Assoc. 2017, 32 (1), 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shu G; Zhang Q; Chen H; Wan H; Li H Effect of five proteases including alcalase, flavourzyme, papain, proteinase K and trypsin on antioxidative activities of casein hydrolysate from goat milk. Acta Univ. Cibiniensis, Ser. E: Food Technol. 2015, 19 (2), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zarei M; Ebrahimpour A; Abdul-Hamid A; Anwar F; Bakar FA; Philip R; Saari N Identification and characterization of papain-generated antioxidant peptides from palm kernel cake proteins. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 726–734. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Chanput W; Theerakulkait C; Nakai S Antioxidative properties of partially purified barley hordein, rice-bran-protein fractions and their hydrolysates. J. Cereal Sci. 2009, 49 (3), 422–428. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Selamassakul O; Laohakunjit N; Kerdchoechuen O; Ratanakhanokchai K A novel multi-biofunctional protein from brown rice hydrolysed by endo/endo-exoproteases. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2635–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Agboola S; Ng D; Mills D Characterisation and functional properties of Australian rice protein isolates. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 41 (3), 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Tang S; Hettiarachchy NS; Horax R; Eswaranandam S Physicochemical properties and functionality of rice-bran-protein hydrolysate prepared from heat-stabilized defatted rice bran with the aid of enzymes. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68 (1), 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Carrasco-Castilla J; Hernández-Álvarez AJ; Jiménez-Martínez C; Jacinto-Hernández C; Alaiz M; Girón-Calle J; Vioque J; Dávila-Ortiz G Antioxidant and metal chelating activities of peptide fractions from phaseolin and bean protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Padhye VW; Salunkhe DK Extraction and characterization of rice proteins. Cereal Chem. 1979, 56, 389–393. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wang C; Li D; Xu F; Hao T; Zhang M Comparison of two methods for the extraction of fractionated rice bran protein. J. Chem. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lee S-J; Park SG; Chung H-M; Choi J-S; Kim D-D; Sung J-H Antioxidant and anti-melanogenic effect of the novel synthetic hexapeptide (SFKLRY-NH2). Int. J. Pept. Res.Ther. 2009, 15, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Megías C; Pedroche J; Yust MM; Girón-Calle J; Alaiz M; Millán F; Vioque J Affinity purification of copper-chelating peptides from chickpea protein hydrolysates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007b, 55, 3949–3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Yi J; Ding Y Dual effects of whey protein isolates on the inhibition of enzymatic browning and clarification of apple juice. Czech J. Food Sci. 2014, 32, 601–609. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Zhuang Y; Sun L; Zhao X; Wang J; Hou H; Li B Antioxidant and melanogenesis-inhibitory activities of collagen peptide from jellyfish (Rhopilema esculentum). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ubeid AA; Do S; Nye C; Hantash BM Potent low toxicity inhibition of human melanogenesis by novel indole-containing octapeptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012, 1820, 1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhuang H; Tang N; Yuan Y Purification and identification of antioxidant peptides from corn gluten meal. J. Funct. Foods. 2013, 5, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Baakdah MM; Tsopmo A Identification of peptides, metal binding and lipid peroxidation activities of HPLC fractions of hydrolyzed oat bran proteins. J. Food Sci.Technol. 2016, 53, 3593–3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Mandal S; Das G; Askari H A combined experimental and quantum mechanical investigation on some selected metal complexes of L-serine with first row transition metal cations. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1081, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Wu Z; Fernandez-Lima FA; Russell DH Amino acid Influence on copper binding to peptides: cysteine versus arginine. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 522–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]