Abstract

A genome manipulation approach based on double-crossover homologous recombination was developed in the polyploid model organism Thermus thermophilus HB27 without the use of any selectable marker. The method was established and optimized by targeting the megaplasmid-encoded β-glucosidase gene bgl. When linear and supercoiled forms of marker-free suicide vector were used for transformations, the frequencies of obtaining apparent Bgl− mutant were 10− 5 and 10− 3, respectively; while the frequency could reach 10− 2 when transformation with concatemer form of the same vector. All randomly selected Bgl− colonies from the transformations were found to be true bgl knockout mutants. Thus, markerless gene deletion mutants could be constructed in T. thermophilus by the direct selection-free method. The functionality of this approach was further demonstrated by deletion of one chromosomal locus (TTC_0340–0341) as well as by generation of a reporter strain for the phytoene synthase promoter (PcrtB), homozygous mutants of the both targets could also be detected with a frequency of approximately 10− 2. During the genome modification process, heterozygous cells carrying two different alleles at a same locus (e.g., bgl and pyrE) could also be generated. However, in the absence of selection pressure, these strains could rapidly convert to homozygous strains containing only one of the two alleles. This indicated that allele segregation could occur in the heterozygous T. thermophilus cells, which probably explained the ease of obtaining homozygous gene deletion mutants with high frequency (10− 2) in the polyploid genomic background, as after the mutant allele had been introduced to the target region, allele segregation would lead to homozygous mutant cells. This marker-free genome manipulation approach does not require phenotype-based screens, and is applicable in gene deletion and tagging applications.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1682-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Thermus thermophilus, Polyploid, Marker-free genome manipulations, Allele segregation

Introduction

Thermus thermophilus has been established as a model organism for studying thermophilic bacteria, this is mainly due to the ease of laboratory cultivation and the presence of an efficient natural transformation system (Koyama et al. 1986; Hidaka et al. 1994). The genome of T. thermophilus HB27 contains a chromosome (1.89 Mb) and a megaplasmid (0.23 Mb), over the last years, several genetic manipulation tools have been developed for this strain (de Grado et al. 1999; Cava et al. 2009; Fujita et al. 2015; Fujita and Misumi 2017). The most convenient method for the generation of knockout mutants in T. thermophilus is based on gene replacement with antibiotic resistance markers, i.e. kanamycin (Hashimoto et al. 2001), hygromycin (Nakamura et al. 2005) or bleomycin resistance genes (Brouns et al. 2005). This approach has inevitable disadvantages, e.g., the specific antibiotic resistance gene cannot be reused and polar effects for down-stream genes are possible. Alternative markerless gene deletion strategy has become attractive for research on T. thermophilus, several methods that rely on selection/counter-selection have been developed, in which the pyrE (Tamakoshi et al. 1999), rpsL (Blas-Galindo et al. 2007), bgl (Angelov et al. 2013), crtB (Fujita et al. 2015), pheS (Carr et al. 2015) or codA (Wang et al. 2016) gene was used as a counter-selectable marker, respectively. Some of these strategies could be used in wild-type background (e.g., the pheS, codA, bgl system), but the others were only applicable in corresponding mutant backgrounds (e.g., the pyrE, rpsL, crtB system). Nevertheless, this strategy requires two selectable markers, and notably, the frequency of spontaneous mutants that were resistant to counter-selection agent was considerably high (Blas-Galindo et al. 2007; Carr et al. 2015). Cre/loxP-based markerless gene disruption system has recently been reported (Togawa et al. 2018), however, it is only applicable for cells grown at the lowest growth temperature (50 °C), and undesired deletion or inversion of genomic regions might occur. Taken together, it seems that selection-free markerless genome manipulation methods are required for T. thermophilus.

T. thermophilus has been suggested to be polyploid which contains 4 to 5 genome copies under slow growth condition (Ohtani et al. 2010). There seems to be a contradiction between polyploidy and the ease with which homozygous gene deletion mutants can be generated in T. thermophilus. It is conceivable that during gene deletion process, heterozygous mutants containing both the wild-type and mutant alleles at the target gene locus would be possible, and the frequency of these strains would be higher than their counterparts. On the other hand, when a non-essential locus was targeted with a DNA fragment which carries an antibiotic resistant marker flanked by sequences from both sides of that locus, practically all of the antibiotic resistant colonies obtained are homozygous gene replacement mutants for that locus (Li et al. 2015; Ohtani et al. 2015). In this study, a versatile method which allows the introduction of mutations into the genome of T. thermophilus HB27 without using any marker for selection was developed. By transforming the wild-type strain with suicide vectors, which contained two homology arms of target genes and no selection marker for T. thermophilus, knockout and other mutants could be obtained with a frequency of approximately 10− 2. Further, it was found that heterozygous mutant cells could be formed during gene deletion process, however, this kind of mutants was genetically unstable, which could convert to homozygous cells carrying either the mutant or wild-type allele. The finding provides an explanation for the possibility of obtaining homozygous mutants with high frequencies in the polyploid T. thermophilus cells, and was utilized to optimize the selection-free markerless genome manipulation method.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a host strain for plasmid constructions and was grown at 37 °C in LB medium (contains 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl). T. thermophilus HB27 wild type (DSM 7039) and derivative strains were grown at 60 °C or 70 °C in TB medium. TB medium contained 8 g/L trypticase peptone (BD Biosciences), 4 g/L yeast extract, and 3 g/L NaCl, and has a pH of 7.5. The growth media were supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/mL for E. coli), kanamycin (50 µg/mL for E. coli and 20 µg/mL for T. thermophilus), bleomycin (“Bleocin”, Calbiochem, 15 µg/mL for E. coli and 3 µg/mL for T. thermophilus) or X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, 100 µg/mL) when necessary. All chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Plasmid construction

All plasmids and strains used are listed in Table S1 and all primers used are listed in Table S2. For construction of the plasmids pUC-Δbgl and pUC-Δ0340–0341, the flanking regions about 1 kbp of the bgl gene (TTP_0042, 1296 bp, encoding β-glucosidase, NCBI accession NO. WP_011174517.1) and TTC_0340–0341 loci (in total 1498 bp, NCBI accession NO.:WP_011172790.1 and WP_011172791.1, respectively) were, respectively, PCR amplified from T. thermophilus HB27, using primers that permitted to generate sufficient overlaps between each other; the two flanking regions of each gene locus were then cloned into XbaI digested pUC18 vector via Gibson Assembly method (New England Biolabs) (Gibson et al. 2009). For the construction of pUC-ΔcrtB::bgl, the complete bgl gene flanked by the upstream and downstream homology arms of crtB gene (TTP_0057, 870 bp, encoding phytoene synthase, NCBI accession NO. WP_011174502.1) was introduced into XbaI digested pUC18 vector via the same approach. For the generation of pJ-ΔpyrE::blm and pJ-ΔpyrE::kat, a 2.3 kbp pyrFE region (pyrE, 552 bp, NCBI accession NO. WP_011173763.1) was PCR amplified and cloned in pJET1.2 giving pJ-pyrFE; two NdeI sites were introduced to pJ-pyrFE through a mutagenesis tool (Change-IT Multiple Mutation Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Affymetrix, USA) at positions − 3 and + 551 relative to the ORF of the pyrE gene. The mutagenized pJ-pyrFE was then digested with NdeI to excise pyrE, and ligated with a bleomycin resistance marker blm (sequence data from Brouns et al. 2005) or a kanamycin resistance marker kat (sequence data from Hashimoto et al. 2001) via the Gibson Assembly method, resulting in pJ-ΔpyrE::blm and pJ-ΔpyrE::kat, respectively.

Transformation experiments

The transformation experiments of T. thermophilus were essentially performed as described by de Grado et al. (1999). pUC-Δbgl, pUC-Δ0340–0341 were transformed into the wild-type strain, and pUC-ΔcrtB::bgl was transformed in the Δbgl background. The plasmid preparations used for transformations were performed using the GenElute™ Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Merck). The transformation experiments with different forms of DNA were performed by addition of 10 µg of plasmid DNA into 1 mL exponentially-growing cell culture. The plasmid DNAs had been enzymatically treated to obtain linear, relaxed or open circular (oc) and concatemer (con) forms. For the preparation of the linear and concatemer forms, 20 µg (1 µg/µL) pUC-Δbgl was digested with NotI, followed by heat inactivation of the enzyme, giving linear form; 10 µg of the linearized DNA was then treated with 5 U of T4 ligase (Thermo Scientific) followed by incubation at 16 °C for 16 h, and due to the high DNA concentration, the con form was obtained. Topoisomerase IV from E. coli (Inspiralis, Norwich, UK) was used to obtain the oc plasmid form as described by Kato et al. (1992). Native plasmid was treated at the same way but omitting the enzyme in the steps and represented the supercoiled (sc) form. For each plasmid form, three independent transformations were carried out.

Isolation and identification of marker-free deletion mutants

To obtain bgl gene clean deletion mutants, dilutions of the transformation reactions were plated on TB agar plates supplemented with X-Gluc, and after incubation at 70 °C for 2 days, yellow colonies (Bgl−) were selected. PCR (with primers flanking the target region) and Southern blot were then used to determine the genotype of these colonies, from which Δbgl mutants were identified. For the Southern blot, a 663 bp biotin-labelled PCR fragment of the TTP0043 ORF was used as a probe, genomic DNA was digested with BamHI (the deleted bgl region contains one BamHI site); to obtain Δ0340–0341, the transformation mixtures were also diluted and streaked on TB plates. 96 colonies were randomly picked out and grown in a 96-well plate, genomic DNAs were isolated by pooling method (8 colonies in one pool). PCR was then used to determine the strain pool which contained the Δ0340–0341 allele. Sequentially, the specific colony containing the mutant allele was sorted out by the same PCR method. The colony was re-grown and re-streaked in TB medium without selection, from which homozygous Δ0340–0341 mutants were identified. For Southern blot confirmation of the Δ0340–0341 mutant, a 959-bp DNA sequence located in the downstream of TTC_0340–0341 was used as template; genomic DNA was digested with SacII. For the generation of ΔcrtB::bgl, the transformation reactions were streaked on TB-X-Gluc plates, followed by incubation under light. The colonies projecting blue color were then analyzed by PCR, from which homozygous ΔcrtB::bgl mutants were isolated.

Determination of frequency of obtaining gene deletion mutants

The frequency of obtaining apparent Δbgl mutants was defined as the ratio of yellow colonies (Bgl−) to the total viable counts on TB agar plates supplemented with X-Gluc. Statistic analysis of the transformation frequency data was performed with the Student’s t test.

Enzyme assays

The exponentially growing cells were collected, and their β-glucosidase activities were measured using pNP-β-glucoside as a substrate, according to the method described in (Ohta et al. 2006). The assays were performed at 80 °C for 60 min in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). For each strain, three independently grown cultures were assayed.

Construction of a stable heterozygous strain and allele segregation experiment

The allele exchange vectors pJ-ΔpyrE::kat and pJ-ΔpyrE::blm were linearized by HindIII, respectively, then transformed into T. thermophilus HB27, generating two homozygous strains, i.e., ΔpyrE::kat and ΔpyrE::blm, which carried either the kat or the blm resistance marker at the pyrE gene locus. Sequentially, linearized pJ-ΔpyrE::blm was transformed into the ΔpyrE::kat strain, by selecting on TB agar plates supplemented with both kanamycin and bleomycin, the heterozygous strain KB01 was obtained. Southern blot and DNA sequencing were used to confirm the genotype of the heterozygous strain. For the Southern blot, biotin-labelled pyrF gene was used as a probe, genomic DNAs were digested with BamHI, homozygous strains ΔpyrE::kat and ΔpyrE::blm were used as controls. The allele segregation experiment was performed as follows: KB01 was initially grown in 5 mL of TB medium supplemented with both antibiotics for 12 h; the cells were then washed three times by 1 × PBS buffer and inoculated in 50 mL antibiotic-free TB medium (time point 0). Growth was continued for 72 h at 70 °C with agitation. Samples (2 mL) were taken at various time points as indicated in the results, and were used to determine the fraction of each phenotype by plating the cells on antibiotic-free TB plates and re-streaking 50 colonies on plates supplemented with bleomycin or kanamycin.

Results

Direct and selection-free deletion of the T. thermophilus bgl gene

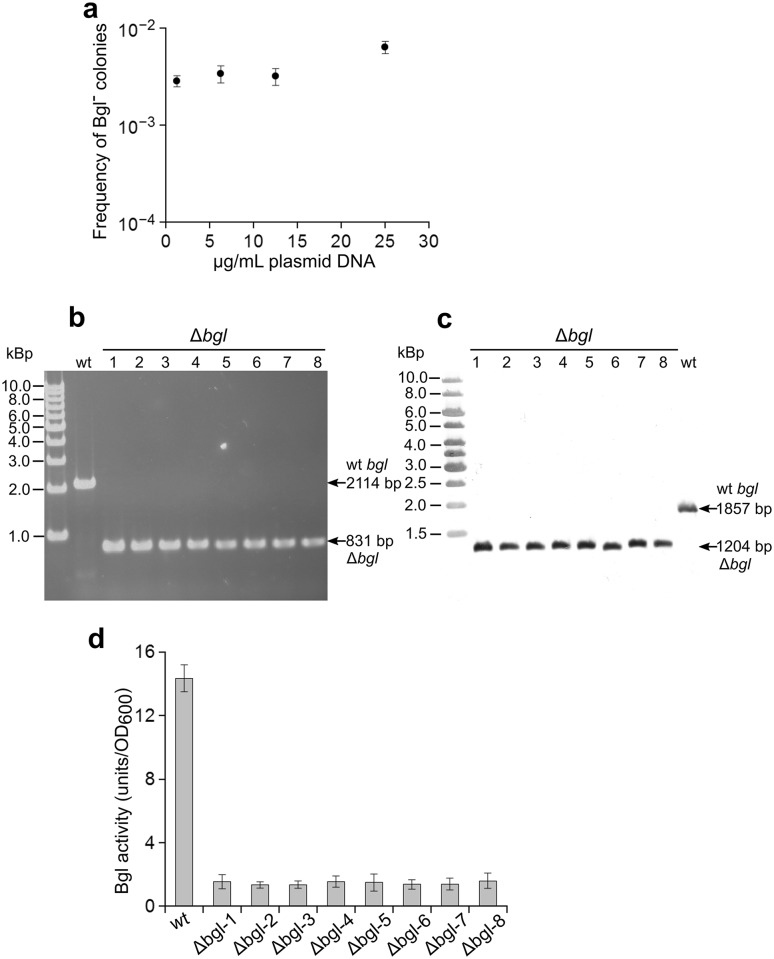

Wild-type T. thermophilus HB27 cells express β-glucosidase (Bgl), which is encoded by the megaplasmid-located gene bgl (TTP_0042). It has been previously shown that the T. thermophilus Δbgl strain shows low Bgl activity and that the gene can be used as a reporter in gene expression studies (Ohta et al. 2006). Thus, it is easy to distinguish Bgl− from Bgl+ colonies on agar plates supplemented with indicator substrate X-Gluc. For the deletion of the bgl gene, a suicidal vector containing fused upstream and downstream homology regions of bgl, designated pUC-Δbgl was used (see “Materials and methods”). After transformation with a serials of different amount of untreated plasmid preparations (supercoiled) and plating on selection-free TB-X-Gluc agar plates, the observed maximal frequency of apparent Bgl− colonies reached 10− 3 per viable count (Fig. 1a). Under the same transformation condition but without the addition of DNA, the frequency of obtaining spontaneous Bgl− mutants was lower than 10− 8. Eight apparent Bgl− colonies were randomly selected, PCR and Southern blot were used to determine the genotype. In all cases tested, the Bgl− cells were found to carry the expected bgl deletion, and no suicide plasmid DNA as well as no wild-type bgl allele was present (Fig. 1b, c). This indicated that in these colonies, the wild-type bgl allele had been completely exchanged by the Δbgl allele carried by the suicide vector pUC-Δbgl. The Δbgl mutants kept stable pheno- and genotype in non-selective medium. The intracellular β-glucosidase activities in these Δbgl mutant cells were approximately 10 folds lower than that in the wild type (Fig. 1d), which is consistent with the determined genotypes and in agreement with the previous reports (Ohta et al. 2006). The residual low activity in the mutants is probably due to unspecific cleavage of the substrate by family 2 glycoside hydrolases encoded by ORFs TTP_0220–0222 (Moreno et al. 2002; Park and Kilbane 2004). The above results indicated that practically all apparent Bgl− colonies obtained from the transformation with supercoiled pUC-Δbgl are true bgl gene clean deletion mutants, resulting from double-crossover event between pUC-Δbgl and the homologous genomic DNA sequence. Taken together, these experiments showed that gene clean-deletion mutants could be obtained at a considerably high frequency in the polyploid T. thermophilus cells by the direct selection-free method.

Fig. 1.

Deletion of the bgl gene in T. thermophilus using direct selection-free method. a Observed frequency of obtaining Bgl− colonies after transformation with different amounts of native preparations of the suicide vector pUC-Δbgl. The mean and SD were from three independent transformations. b, c Confirmation of the Δbgl genotype of 8 apparent Bgl− colonies by PCR (b) and Southern blot (c). The in silico predicted sizes of the wild-type and clean-deleted bgl regions are indicated with arrows on the right side of each image. d Intracellular β-glucosidase activity (Miller units) of the 8 Δbgl mutants and the wild-type strain. Shown are the mean and SD from three independent assays

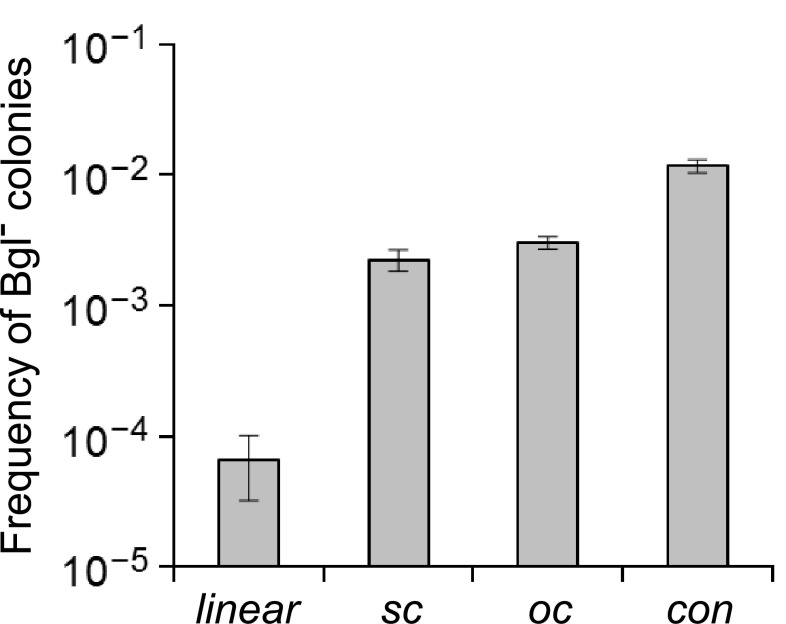

Effect of the topology of the suicidal vector on the frequency of bgl knockouts

Using the above gene deletion protocol as a convenient assay, the apparent frequencies of obtaining bgl gene knockouts with different forms of the pUC-Δbgl plasmid were measured. Prior to transformation, one plasmid preparation was split and subjected to enzymatic modifications which yielded linear, relaxed or open circular (oc) and concatemer (con) forms. The native plasmid preparation was considered to consist mainly of the supercoiled form (sc), although small amounts of the other plasmid forms were also present. The results of these transformations are summarized in Fig. 2. The linear form was found to yield significantly fewer Bgl− colonies than the other DNA types (P = 1.20 × 10− 4, n = 14, t test between the linear and con groups), while the frequency of the sc and oc forms was the same (P = 0.78, n = 14). Significantly more Bgl− mutants were observed when the T. thermophilus HB27 cells were transformed with the con DNA form as compared to the sc or oc form (P = 1.69 × 10− 3, n = 14, t test between the oc and con groups), which reached 10− 2.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of obtaining apparent Δbgl colonies after transformation with different forms of the pUC-Δbgl vector. The data are the mean and SD of three independent measurements; linear linearized plasmid, sc supercoiled, oc open circular, con concatemers

Theoretically, the observed high frequency of bgl knockouts could be the result of a much higher growth rate of the Δbgl cells, which perhaps could outgrow the wild type in the 2 h incubation step after DNA addition during the transformation procedure. To test this, a 1:1 mixture of the Δbgl and the wild-type strains were grown in TB medium and followed the viable cell counts of each strain by plating on agar plates supplemented with X-Gluc. The ratio of the counts of the two strains remained constant, even after 8 h of incubation (P = 0.44, n = 6, t test for the significance of the variation between the time points 0 and 8 h), which clearly showed that the high frequency of obtaining Δbgl mutants was not due to growth rate effects. Taken together, this experiment succeeded in increasing the frequency of obtaining knockout mutants generated via the selection-free method.

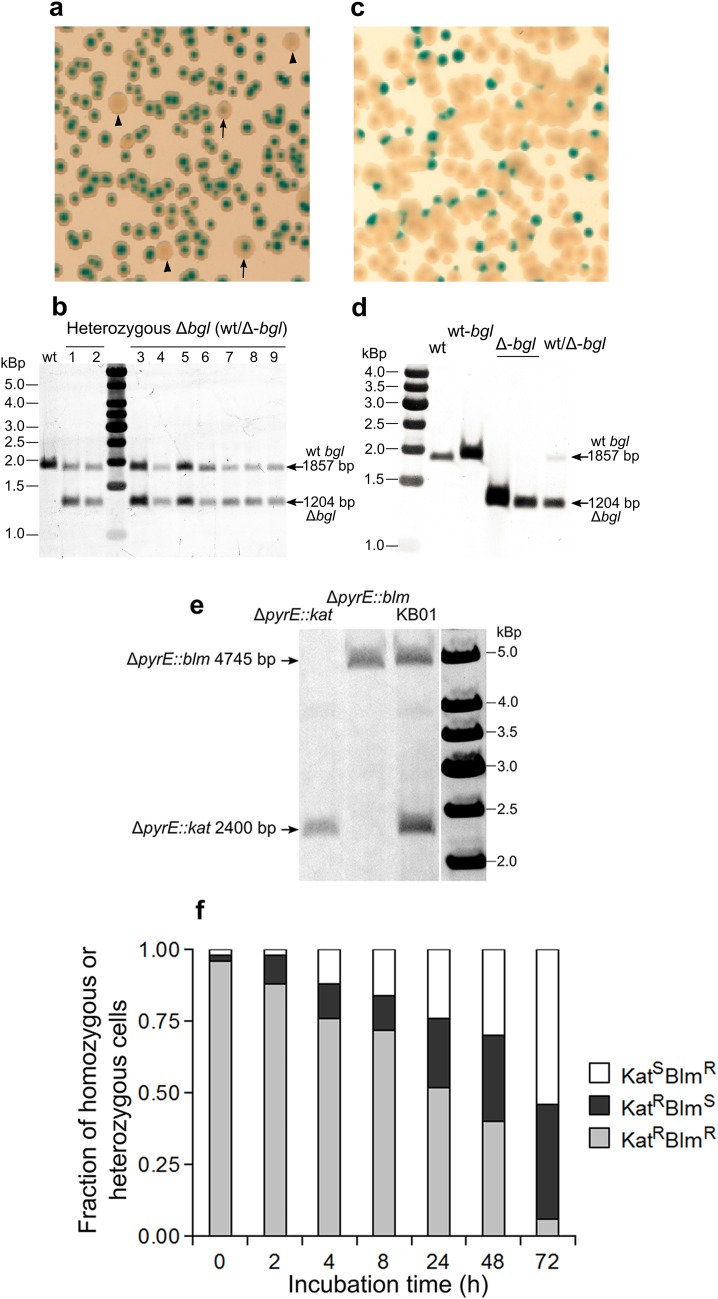

Allele segregation in heterozygous cells

During the process of generating bgl knockouts by the direct method, some transformants were found to show intermediate phenotype on TB-X-Gluc plate, i.e. the color of the colonies was between yellow and blue (Fig. 3a). The genotypes of 9 “intermediate” colonies were determined by Southern blot. As shown in Fig. 3b, the Δbgl signal was not from pUC-Δbgl vector integration event, thus the tested colonies were carrying both the wild-type and Δbgl alleles simultaneously at the bgl locus, i.e. they were heterozygous wt/Δ-bgl mutants. Upon growing and re-streaking the heterozygous colonies on TB-X-Gluc plates, progeny colonies showing either yellow (Bgl−) or blue color (Bgl+) were observed (Fig. 3c). Southern blot analysis showed that the yellow colonies only contained the Δbgl allele, and the blue ones only contained the wild-type allele (Fig. 3d). These results indicated that allele segregation had occurred in the heterozygous cells.

Fig. 3.

Allele segregation in heterozygous T. thermophilus cells. a Phenotype of heterozygous wt/Δ-bgl colonies on TB-X-Gluc plate. Intermediate colonies (heterozygous, Bgl+/Bgl−) are pointed with arrows, yellow colonies (homozygous, Bgl−) are indicated with triangles. b Genotype of 9 colonies showing intermediate phenotype were determined by Southern blot. c, d The resultant phenotype (c) and genotype (d) of the heterozygous wt/Δ-bgl mutant after growing without selection and re-streaking on TB-X-Gluc plate. wt-bgl: genotype of the blue colonies, Δ-bgl: genotype of the yellow colonies. e Genotype confirmation of the stable heterozygous strain KB01 by Southern blot. The expected sizes are indicated with arrows. f Allele segregation kinetics of the KB01 strain. Shown are changes of the fraction of each phenotype (KatRBlmR—grey bar, KatRBlmS—black bar and KatSBlmR—white bar) in the population

To further support the suggestion, a conditionally stable heterozygous strain KB01 was constructed (see "Materials and methods"). Southern blot and DNA sequencing were used to confirm the genotype of the KB01 strain, which excluded the possibility of vector integration and existence of any copy of wild-type pyrE allele, and explicitly showed that in KB01 the pyrE gene was completely replaced by both the kat and blm resistance markers simultaneously (Fig. 3e). Using TB medium supplemented with both kanamycin and bleomycin, the heterozygous state of the KB01 strain could be stably maintained. To detect and quantify allele segregation in T. thermophilus heterozygous cells, KB01 was grown in the absence of selection pressure for 72 h. The culture was sampled at various time points, and the changes of the fraction of each phenotype (KatRBlmR, KatRBlmS, and KatSBlmR) in the population were scored by spreading the samples on antibiotic-free plates and restreaking 50 colonies for each time point on plates containing bleomycin or kanamycin. As expected, during growth without selection pressure, the fraction of heterozygous cells (as determined by the resistance phenotype) decreased and that of homozygous cells increased apparently (Fig. 3f). The data from the above experiments further confirmed that the polyploid T. thermophilus cells could form heterozygous state, which would convert to homozygous state under the growth conditions without selection pressure. Together, the allele segregation mechanism probably explains the ease with which to obtain homozygous gene deletion mutants with high frequency in the polyploid T. thermophilus cells as observed in Fig. 2.

Application of the direct and selection-free gene exchange method to other genomic loci

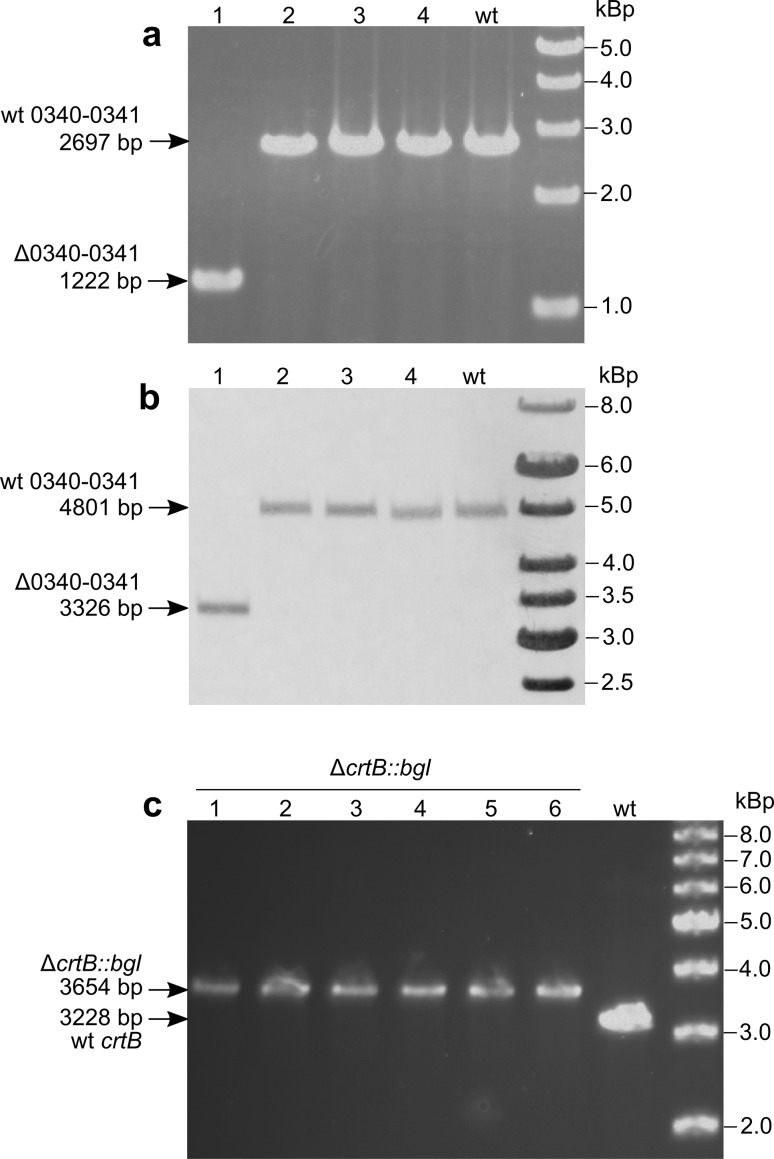

It was of interest to test whether the above high efficient gene clean deletion method, was applicable to target other genes/loci than bgl, In addition, since the bgl gene is located on the megaplasmid, it was not clear if chromosomal sequences can be deleted with comparably high frequency. To test this, a suicide vector that targeted two continuous genes (ORF TTC_0340 and TTC_0341, encoding putative alpha/beta hydrolases) was used. The con form of this plasmid was transformed in the wild-type strain and appropriate dilutions of the transformation mixture were streaked on non-selective agar plates. 96 colonies were selected and distributed into 12 pools (i.e. 8 colonies in one pool) which were subjected to PCR detection of the Δ0340–0341 allele. One pool was found to contain the Δ0340–0341 allele (Supplementary Fig. S1a), and from which two colonies were determined to contain the mutant allele in a heterozygous state (Fig. S1b). One of the two colonies was grown without selection for 16 h, and the culture was plated on selection-free plates. PCR and Southern blot showed that the resultant colonies were homozygotes containing either the mutant or wild-type 0340–0341 allele (Fig. 4a, b). Therefore, the allele segregation property in heterozygous cells contributed to simplify the marker-free deletion method. As when the mutant allele was found in a heterozygous state with the wild-type allele, it was sufficient to grow the cells from such colonies in liquid medium and re-streak on selection-free agar plates to obtain homozygous gene deletion mutants. The above example also showed that this method could be used in genomic loci without the need to perform any phenotype-based screens.

Fig. 4.

Application of the selection-free gene exchange method in T. thermophilus TTC_0340–0341 and TTP_0057 loci. a, b Heterozygous Δ0340–0341 cells were re-grown and re-streaked on TB plate, from which 4 colonies were randomly selected and the genotypes were determined by PCR (a) and Southern blot (b). c Genotype determination of 6 apparent ΔcrtB::bgl colonies by PCR. The expected sizes are indicated with arrows on the left side of each image

It has been shown that the T. thermophilus phytoene synthase gene crtB (TT_P0057) is under light-dependent transcriptional control (Takano et al. 2011). Thus, a reporter T. thermophilus strain in which the crtB gene replaced with the bgl gene was created. It was achieved by transforming the con form of the pUC-ΔcrtB::bgl plasmid to the T. thermophilus Δbgl strain, and a phenotype screen based on the known response of PcrtB to illumination was performed. It was expected that in ΔbglΔcrtB::bgl strain, the expression of the bgl ORF should be light-inducible. In agreement with the data obtained for the knockout mutants, approximately 1 out of 100 colonies from the transformation mixture turned blue on TB-X-Gluc agar plates only after light exposure, indicating a successful allelic exchange. The genotype of 6 of these blue colonies was verified by PCR, which showed that crtB was completely replaced with bgl (Fig. 4c). This experiment indicated that the described method was useful also for performing precise genome modifications other than deletions.

Discussion

A genome manipulation method based on direct double-crossover homologous recombination was created, it was initially established and optimized using the bgl gene as the target for deletion, and then utilized in the TTC_0340–0341 and TTP_0057 loci. Stable homozygous clean deletion mutants could be obtained at a frequency of 10− 2 when the concatemer (con) plasmid forms were used for transformation. After the mutant allele had been introduced in the genome by transformation, cells would become heterozygous, however, subsequent allele segregation in these cells would lead to homozygous mutant cells, this should be the main reason for the ease of obtaining homozygous gene deletion mutants in the polyploid T. thermophilus cells. The other properties contributing to the high frequency of obtaining knockout mutants are that T. thermophilus is able to uptake DNA and execute homologous recombination efficiently. In fact, T. thermophilus has been shown to be the microorganism which possesses the highest efficient natural transformation system known to date (Salzer et al. 2014), the DNA uptake efficiency of T. thermophilus HB27 has been estimated at approx. 40 kbp × s− 1 × cell− 1 (Schwarzenlander and Averhoff 2006). It could be expected that compared with monomeric sc or oc plasmid molecules the concatemer form had led to the uptake of a larger number of mutant allele copies per cell (Fig. 2). The linear plasmid form generated the lowest frequency of knockout mutants (10− 5). A possible explanation is that degradation of the free ends by exonucleases occurred severely in the linear DNA, which might decrease the length of the homology regions needed for recombination. A similar frequency of obtaining targeted gene deletion mutants with linearized plasmids has been reported in the presence of selection for other genes in T. thermophilus (Schwarzenlander and Averhoff 2006). The phenomenon that the linear plasmid form would yield lower transformation frequency was also observed in some other bacteria, for example, in Lactobacillus plantarum, the covalently closed circular plasmid DNA is capable of electrotransforming at a frequency 500-fold higher than with linearized molecule (Thompson et al. 1997); in Bacillus subtilus, Ohse et al. (1997) reported that the transformation efficiency was zero for the linearized plasmid form.

It has been suggested that polyploid extreme prokaryotes generally possess efficient homologous recombination (HR) systems, which will facilitate repairment of double-strand breaks triggered by radiation, desiccation or other extreme conditions (Soppa 2013, 2014, 2017; Zerulla and Soppa 2014). In Deinococcus radiodurans and Halobacterium salinarum, the ionizing radiation-shattered chromosomal fragments could be rapidly reassembled due to homologous recombination among multiple broken genome copies (Kottemann et al. 2005; Zahradka et al. 2006; Slade et al. 2009). In T. thermophilus, the recA gene (encoding one of the recombinases for HR) deletion mutant had extremely low viability with the increase of growth temperature (Castán et al. 2003). This indicated that T. thermophilus might be suffered from frequent double-strand DNA breaks during growth at high temperature, and in response, the polyploid cells would provide efficient HR system for DNA repair. Taken together, the prominent DNA uptake rate in combination with the efficient homologous recombination system of T. thermophilus also allow the observed high frequency of obtaining gene deletion mutants in this bacterium.

During the deletion of the bgl gene, heterozygous mutant containing both the muant and wild-type alleles at the bgl locus simultaneously were observed, and this kind of mutant was unstable, since after growing and re-streaking, colonies that were homozygous for either the wide-type or mutant allele were obtained (Fig. 3a–d), which indicated that allele segregation had occurred in the heterozygous cells. Through constructing a stable heterozygous T. thermophilus strain (KB01) followed by performing allele segregation kinetics experiment (Fig. 3e, f), the above suggestion was strengthened. This allele segregation phenomenon has also been observed in the HB8 strain (Ohtani et al. 2010). The intrinsic mechanism of the allele segregation in T. thermophilus has not been elucidated, however, it is possibly caused either by random chromosome segregation or gene conversion, which will both result in homogeneity in the progeny. Random segregation of chromosome copies has indeed been proposed for some polyploid prokaryotes, such as the euryarchaeotal species Methanococcus jannaschii (Malandrin et al. 1999), and the cyanobacterial species Anabaena sp. 7120 (Hu et al. 2007) and Synechocystis sp. (Schneider et al. 2007) based on DNA content analysis in dividing cells. On the other hand, allele equalization via gene conversion has also been demonstrated in polyploid methanogenic and halophilic archaea, i.e., Methanococcus maripaludis and Haloferax volcanii (Hildenbrand et al. 2011; Lange et al. 2011). Nevertheless, the property could be well utilized in the described selection-free gene deletion method, when deletion of the non-essential genes producing phenotypes which are not easy to be detected, it is sufficient to obtain colonies carrying the mutant allele first, and then grow the cells of such colonies without selection pressure to promote formation of homozygous knockout mutants.

In conclusion, based on the merits of T. thermophilus, i.e., the efficient natural competence, the high homologous recombination frequency, and the ability that heterozygous cells can be converted to homozygous cells, a selection-free genome manipulation method was created. The main advantages of this approach are (i) to date, it is the most direct and simplest method compared with all other reported genome manipulation systems in T. thermophilus, as no selection and counterselection markers or other elements are needed, which will shorten the genome manipulation procedure to a great extent; (ii) it can be used in the wild-type background, i.e., no prior genetic modifications are necessary; (iii) spontaneous mutants are impossible to be detected using this protocol, as the mutants can be determined based on genotypes directly other than phenotypes. Further, apart from its use in T. thermophilus, it is possibly used in other polyploid bacteria or archaea, such as H. volcanii, as long as they have efficient homologous recombination systems and/or the ability to convert heterozygotes into homozygotes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31700059), Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (No. 2018JQ3037) and Young Talent Fund of University Association for Science and Technology in Shaanxi, China (Grant Number 20180210).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Angelov A, Li H, Geissler A, Leis B, Liebl W. Toxicity of indoxyl derivative accumulation in bacteria and its use as a new counterselection principle. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blas-Galindo E, Cava F, López-Viñas E, Mendieta J, Berenguer J. Use of a dominant rpsL allele conferring streptomycin dependence for positive and negative selection in Thermus thermophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5138–5145. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00751-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns SJJ, Wu H, Akerboom J, Turnbull AP, de Vos WM, van der Oost J. Engineering a selectable marker for hyperthermophiles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11422–11431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JF, Danziger ME, Huang AL, Dahlberg AE, Gregory ST. Engineering the genome of Thermus thermophilus using a counterselectable marker. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:1135–1144. doi: 10.1128/JB.02384-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castán P, Casares L, Barbé J, Berenguer J. Temperature dependent hypermutational phenotype in recA mutants of Thermus thermophilus HB27. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4901–4907. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4901-4907.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cava F, Hidalgo A, Berenguer J. Thermus thermophilus as biological model. Extremophiles. 2009;13:213–231. doi: 10.1007/s00792-009-0226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Grado M, Castan P, Berenguer J. A high-transformation-efficiency cloning vector for Thermus thermophilus. Plasmid. 1999;42:241–245. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita A, Misumi Y. Development of a new host-vector system for colour selection of cloned DNA inserts using a newly designed β-galactosidase gene containing multiple cloning sites in Thermus thermophilus HB27. Extremophiles. 2017;21:1111–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00792-017-0961-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita A, Sato T, Koyama Y, Misumi Y. A reporter gene system for the precise measurement of promoter activity in Thermus thermophilus HB27. Extremophiles. 2015;19:1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s00792-015-0789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, III, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, Yano T, Kuramitsu S, Kagamiyama H. Disruption of Thermus thermophilus genes by homologous recombination using a thermostable kanamycin-resistant marker. FEBS Lett. 2001;506:231–234. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02926-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka Y, Hasegawa M, Nakahara T, Hoshino T. The entire population of Thermus thermophilus cells is always competent at any growth phase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:1338–1339. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildenbrand C, Stock T, Lange C, Rother M, Soppa J. Genome copy numbers and gene conversion in methanogenic archaea. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:734–743. doi: 10.1128/JB.01016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Yang G, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Zhao J. MreB is important for cell shape but not for chromosome segregation of the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1640–1652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J, Suzuki H, Ikeda H. Purification and characterization of DNA topoisomerase IV in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25676–25684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottemann M, Kish A, Iloanusi C, Bjork S, DiRuggiero J. Physiological responses of the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium sp strain NRC1 to desiccation and gamma irradiation. Extremophiles. 2005;9:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Y, Hoshino T, Tomizuka N, Furukawa K. Genetic transformation of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus and of other Thermus spp. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:338–340. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.338-340.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange C, Zerulla K, Breuert S, Soppa J. Gene conversion results in the equalization of genome copies in the polyploid haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Angelov A, Pham VT, Leis B, Liebl W. Characterization of chromosomal and megaplasmid partitioning loci in Thermus thermophilus HB27. BMC Genom. 2015;16:317. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1523-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandrin L, Huber H, Bernander R. Nucleoid structure and partition in Methanococcus jannaschii: an archaeon with multiple copies of the chromosome. Genetics. 1999;152:1315–1323. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno R, Zafra O, Cava F, Berenguer J. Development of a gene expression vector for Thermus thermophilus based on the promoter of the respiratory nitrate reductase. Plasmid. 2002;49:2–8. doi: 10.1016/S0147-619X(02)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Takakura Y, Kobayashi H, Hoshino T. In vivo directed evolution for thermostabilization of Escherichia coli hygromycin B phosphotransferase and the use of the gene as a selection marker in the host-vector system of Thermus thermophilus. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100:158–163. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohse M, Kawade K, Kusaoke H. Effects of DNA topology on transformation efficiency of Bacillus subtilis ISW1214 by electroporation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:1019–1021. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Tokishita S, Imazuka R, Mori I, Okamura J, Yamagata H. Glucosidase as a reporter for the gene expression studies in Thermus thermophilus and constitutive expression of DNA repair genes. Mutagenesis. 2006;21:255–260. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani N, Tomita M, Itaya M. An extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus, is a polyploid bacterium. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5499–5505. doi: 10.1128/JB.00662-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani N, Tomita M, Itaya M. Curing the Megaplasmid pTT27 from Thermus thermophilus HB27 and maintaining exogenous plasmids in the plasmid-free strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;82:1537–1548. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03603-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Kilbane JJ., II Gene expression studies of Thermus thermophilus promoters PdnaK, Parg and Pscs-mdh. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2004;38:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer R, Joos F, Averhoff B. Type IV pilus biogenesis, twitching motility, and DNA uptake in Thermus thermophilus: discrete roles of antagonistic ATPases PilF, PilT1, and PilT2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:644–652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03218-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D, Fuhrmann E, Scholz I, Hess WR, Graumann PL. Fluorescence staining of live cyanobacterial cells suggest non-stringent chromosome segregation and absence of a connection between cytoplasmic and thylakoid membranes. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenlander C, Averhoff B. Characterization of DNA transport in the thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus HB27. FEBS J. 2006;273:4210–4218. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade D, Lindner AB, Paul G, Radman M. Recombination and replication in DNA repair of heavily irradiated Deinococcus radiodurans. Cell. 2009;136:1044–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soppa J. Evolutionary advantages of polyploidy in halophilic archaea. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:339–343. doi: 10.1042/BST20120315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soppa J. Polyploidy in archaea and bacteria: about desiccation resistance, giant cell size, long-term survival, enforcement by a eukaryotic host and additional aspects. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:409–419. doi: 10.1159/000368855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soppa J. Polyploidy and community structure. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:16261. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Kondo M, Usui N, Usui T, Ohzeki H, Yamazaki R, Washioka M, Nakamura A, Hoshino T, Hakamata W, Beppu T, Ueda K. Involvement of CarA/LitR and CRP/FNR family transcriptional regulators in light-induced carotenoid production in Thermus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2451–2459. doi: 10.1128/JB.01125-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamakoshi M, Yaoi T, Oshima T, Yamagishi A. An efficient gene replacement and deletion system for an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;173:431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, Mcconville KJ, Mcreynolds C, Collins MA. Electrotransformation of Lactobacillus plantarum using linearized plasmid DNA. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;25:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1997.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togawa Y, Nunoshiba T, Hiratsu K. Cre/lox-based multiple markerless gene disruption in the genome of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus. Mol Genet Genomics. 2018;293:277–291. doi: 10.1007/s00438-017-1361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Hoffmann J, Watzlawick H, Altenbuchner J. Markerless gene deletion with cytosine deaminase in Thermus thermophilus strain HB27. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:1249–1255. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03524-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradka K, Slade D, Bailone A, Sommer S, Averbeck D, Petranovic M, Lindner AB, Radman M. Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature. 2006;443:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerulla K, Soppa J. Polyploidy in haloarchaea: advantages for growth and survival. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:274. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.