Abstract

Although chebulic acid isolated from Terminalia chebular has diverse biological effects, its effects on the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and the expression of downstream genes have not been elucidated. The purpose of this research is to investigate the hepatoprotective mechanism of chebulic acid against oxidative stress produced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP) in liver cells. The treatment with chebulic acid attenuated cell death in t-BHP-induced HepG2 liver cells and increased intracellular glutathione content, upregulated the activity of heme oxygenase-1, and also increased the translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus and Nrf2 target gene expression in a dose-dependent manner. The exposure of chebulic acid activated the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. The overall result is that chebulic acid has cytoprotective effect on t-BHP-induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cells through Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzymes.

Keywords: Chebulic acid, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, Heme oxygenase-1, γ-Glutamate cysteine ligase, Mitogen-activated protein kinases

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by normal cellular metabolism have beneficial effects such as cytotoxicity against pathogens (Muriel, 2009). However, excessive ROS production can cause oxidative stress (Kovacic and Jacintho, 2001) and damage to cell structures (Valko et al., 2007). Therefore, the balance between generation and elimination of ROS is important aspect to living organism and achieved by redox homeostasis (Droge, 2002).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-antioxidant response element (ARE) signaling pathway is a major mechanism in the cellular defense against oxidative stress and controls the gene expression of phase II detoxification/antioxidant enzymes such as γ-glutamine cysteine ligase (γ-GCL), glutathione-S-transferase (GST), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione S-transferase A1/2, and NAD(P)H:quinine oxidoreductase 1 (McMahon et al., 2001). The presence of a stimulus including oxidants and phenolic antioxidants leads to dissociate Nrf2 from Nrf2-Keap1 complex and translocate Nrf2 into the nucleus where it binds to the ARE to regulate its related gene expression (Nguyen et al., 2004). In addition, phosphorylation of specific serine or threonine residues present in Nrf2 by upstream kinases such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) (Zipper and Mulcahy, 2003), protein kinase C delta (Huang et al., 2000), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt (Rojo et al., 2008), and 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Liu et al., 2011) has been considered to facilitate the nuclear localization of Nrf2 (Surh et al., 2008).

Terminalia chebula Retzius is a native plant in India and Southeast Asia and its dried ripe fruit traditionally used as a medicinal plant for a long time in those regions (Perry and Metzger, 1980). In China, the fruit is used as a carminative, deobstruent, astringent, and expectorant agent and also as a remedy for salivating and heartburn (Cheng et al., 2003). T. chebula Retz. has been reported for its biological activities including anticancer (Saleem et al., 2002), antidiabetic (Sabu and Kuttan, 2002), antimutagenic (Kaur et al., 1998), antibacterial (Malekzadeh et al., 2001), antifungal (Vonshak et al., 2003), and antiviral (Ahn et al., 2002) activities. Although there are many such effects, the effect of chebulic acid on Nrf2-activated molecular mechanisms involved in oxidative stress is not known. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether hepatoprotective effect of chebulic acid against oxidative stress produced by t-BHP is modulated by activation of Nrf2 and induction of its target genes in HepG2 cell which was derived from human liver.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin streptomycin, trypsin–EDTA was purchased from Hyclone (Logan, UT) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), tert-Butyl hydroperoxide, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA), reduced glutathione (GSH), oxidized GSH (GSSG), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), triethanolamine, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD), 2-vinylpyridine, glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P), hemin and β-nicothinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced form (NADPH) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membrane was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Nrf2 (sc-722), ERK (sc-93), JNK (sc-571) and PCNA (sc-56) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). p-ERK 1/2 (9101), p-JNK (9251), p38 (9212) and p-p38 (9211) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). GAPDH (2271144) antibody was purchased from Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA, USA).

Isolation and preparation of chebulic acid

Chebulic acid was isolated from dried ripe fruits of T. chebula Retz. as previously published method (Lee et al., 2007). T. chebula Retz. purchased from Kyungdong Herb-Market in Seoul, Korea, in January 2014, and identified by Prof. Kwon-Woo Park (College of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Korea University, Seoul, Korea). In the herbarium of the College of Life Sciences and Biotechnology of Korea University, a voucher specimen has been registered as KUST-2014-01-01.

Cell culture and viability assay

HepG2 cells, which was derived from Human liver, were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and incubated in MEM medium containing 2.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 100 units/mL of streptomycin and penicillin and 10% FBS (v/v). Cells were cultivated at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. HepG2 cells (1.5 × 105 cells/well) were cultured for 24 h in 24-well plates. Cells were pretreated for 24 h with various concentration of chebulic acid (0.4, 2, 10 μM). After then treated with 700 μM t-BHP for 2 h. Medium was altered to 5 mg/mL MTT reagent and the plate was cultured at 37 °C for 3 h. The medium was eliminated and DMSO was added to lyse the intracellular formazan crystals. Cell viability was measured by using multiplate spectrometer at 540 nm.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

The intracellular ROS generation was measured using DCFH-DA assay. 2.0 × 104 cells/well of HepG2 cells were cultured for 24 h in 96-well plates and were pretreated with various concentration of chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) for 24 h. Then, the cells were cultured for 30 min with 100 mM DCFH-DA. The cells were rinsed with pH 7.4 phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and treated with 700 μM t-BHP. After 2 h incubation, Fluorescence of DCF converted by ROS was recorded using a VICTOR3™ (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, U.S.A) spectrofluorometer at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm.

Reduced and oxidized glutathione contents analysis

GSH contents were measured using a modified method as previously reported (Moron et al., 1979). GSSG was determined enzymatically based on the recycling reaction of GSH and DTNB in the presence of glutathione reductase.

Determination of HO-1 activity

HO-1 enzyme activity was measured by bilirubin generation. Briefly, 200 μL HepG2 microsome fraction was added to the reaction mixture (0.2-unit G-6-PD, 20 mM hemin, 2 mM G-6-P, 0.8 mM NADPH, 2 mg/mL microsome fraction from HepG2 cells) and incubated at 37 °C. After 1 h, the mixture was allowed to stand on ice for 5 min and then measured using a spectrophotometer (PowerWaveXS, BioTek, Winooski, VT, U.S.A.) at two wavelengths, 464 nm and 530 nm.

Preparation of nuclear fraction

The nuclear extract was prepared as previously described in detail (Yang et al., 2017). The supernatant containing nuclear protein extract was gathered and stored at − 70 °C.

Western blot analysis

Samples of the same amount of protein were separated on a 10% SDS gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies against Nrf2, phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and nonphosphorylated MAPK. The blot was developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Abclon, Seoul, Korea). Bands were quantified by Image J software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from HepG2 cells using RNAiso Plus system (Takara, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). Total RNA (1 μg) were reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Super ScriptIII First Strand Synthesis System (Legene Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). The synthesized cDNA amplified by PCR using the following primers; GCLM, forward: ATCAAACTCTTCATCATCAAC, reverse: GATTAACTCCATCTTCAATAGG; GCLC, forward: AGTTGAGGCCAACATGCGAA, reverse: TGAAGCGAGGGTGCTTGTTT; HO-1, forward: 5′-GGAACTTTCAGAAGGGCCAG -3′, reverse: GTCCTTGGTGTCATGGGTCA; GAPDH, forward: AGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTG, reverse: ACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTG. RT-PCR was conducted as previously described in detail (Yang et al., 2015). qRT-PCR was performed by the real-time SYBR Green method on a BioRad iQ-5 thermal cycler according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The relative expression level of mRNA was calculated using GAPDH as housekeeping gene using the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) values of at least 3 independent experiments. Duncan’s multi-range test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare groups. SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results and discussion

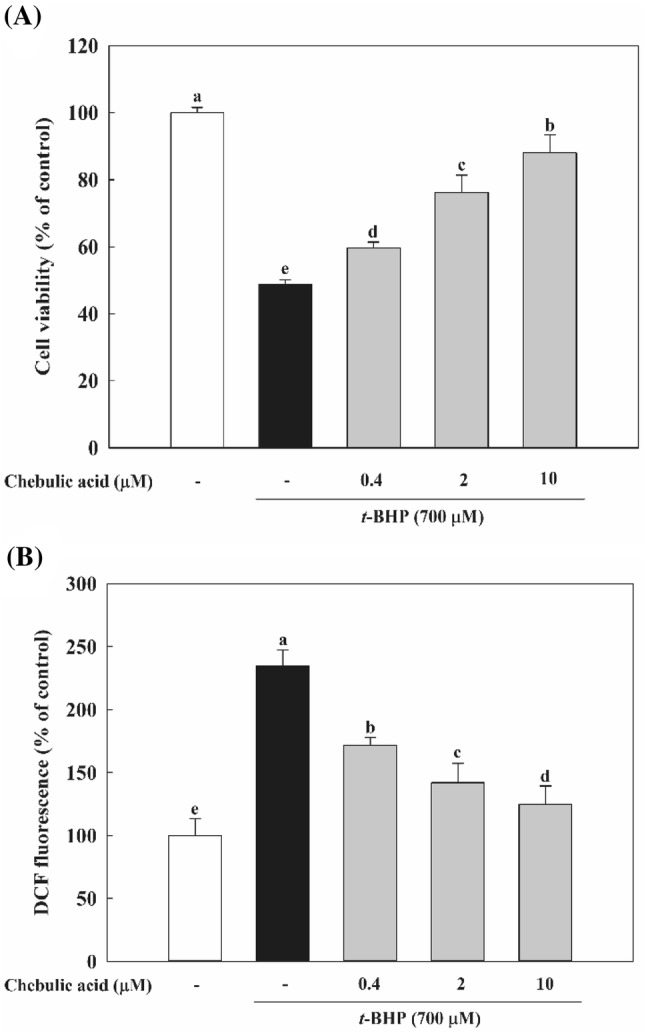

Protective effects of chebulic acid on t-BHP-induced oxidative stress and inhibition of ROS production in HepG2 cells

MTT assay was carried out in HepG2 cells to determine the cytoprotective effect of chebulic acid. HepG2 cells pretreated with chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) and treated with t-BHP (Fig. 1A). Treatment of t-BHP increased HepG2 cells death by 48.8% compared to untreated group, while pretreatment of chebulic acid for 24 h exhibited a significant protective effect in HepG2 cells from oxidative stress induced by t-BHP (Fig. 1A). Also, t-BHP increased the intracellular ROS level by 2.3 folds compared to control group. However, the pretreatment of chebulic acid effectively restrained this induction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of chebulic acid on t-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP)-induced hepatotoxicity and inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in HepG2 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with chebulic acid (0.4, 2 and 10 μM) for 24 h, and then incubated with t-BHP (700 μM) for 2 h. (B) Cells were pretreated with chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) for 24 h, and stained with DCFH-DA (100 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, cells were incubated with t-BHP (700 μM) for 2 h and increase ROS production. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of 3 experiments with triplicate samples and different letters indicate statistical significance of differences among each group at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s test

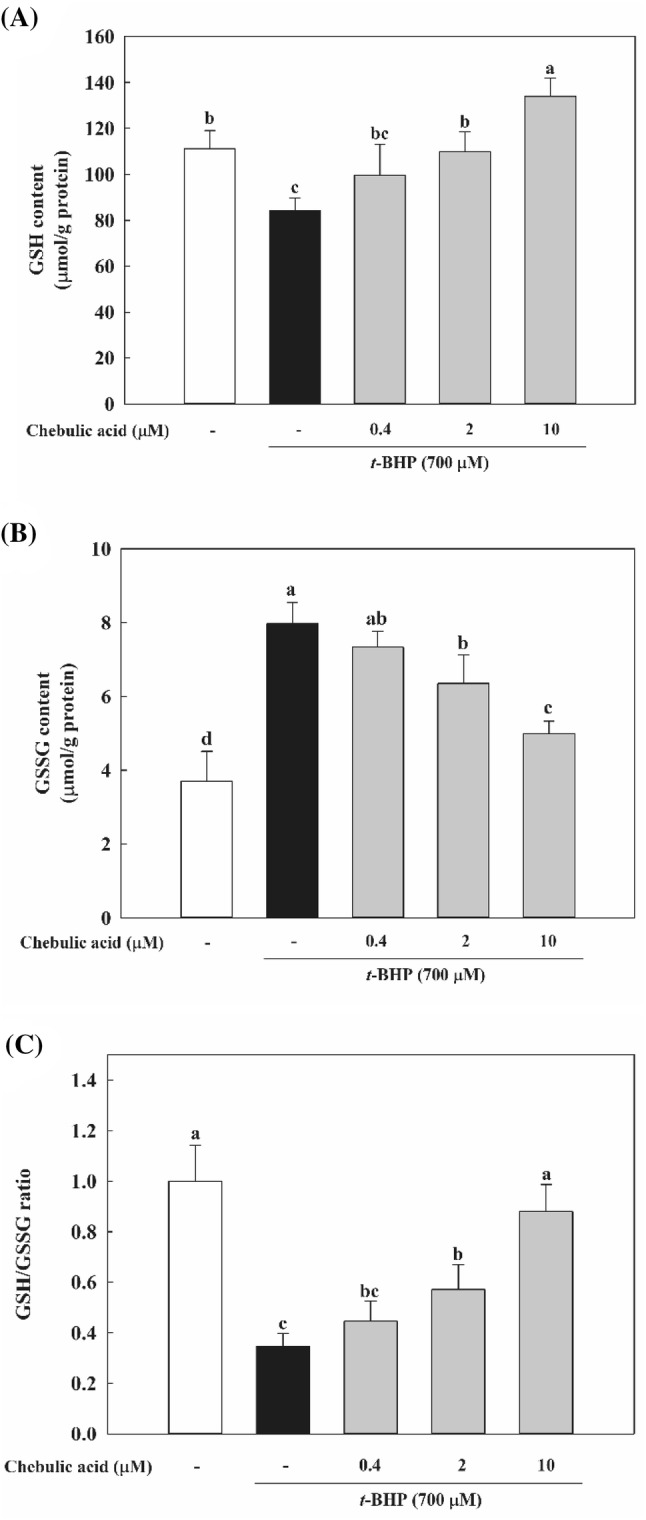

Effects of chebulic acid on glutathione level in HepG2 cells

GSH is one of the main defense systems against oxidative stress present in the cell and directly scavenges ROS. The status of GSH in terms of GSH level and ratio of GSH/GSSG is considered as a sensitive index of oxidative stress (Bains and Shaw, 1997). As shown in Fig. 2A, t-BHP significantly depleted the content of GSH in comparison with control group. Whereas t-BHP treatment increased GSSG level, pretreatment with chebulic acid decreased intracellular GSSG level (Fig. 2B). As a result, GSH/GSSG ratio was decreased by 65.4% in the t-BHP group compared to control group and increased by pretreatment with chebulic acid in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Effects of chebulic acid on glutathione (GSH) levels in t-BHP-induced HepG2 cells. Cells were pretreated with chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) for 24 h and then incubated with 700 μM t-BHP for 2 h. (A) GSH levels were estimated by colorimetric method. (B) Glutathione disulfide (GSSG) levels were determined by enzymatic recycling method. GSH/GSSG ratio is shown (C). Data represent the mean ± S.D. of 3 experiments with triplicate samples and different letters indicate statistical significance of differences among each group at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s test

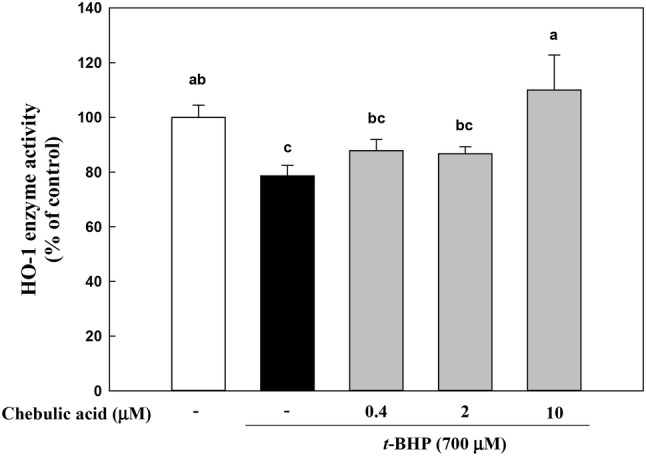

Effect of chebulic acid on HO-1 enzyme activity

Bilirubin has strong free radical scavenging capabilities and has a great effect on the protective effect of the HO-1. Over the past years, HO-1 has been implicated in the cytoprotective defense response against oxidative injury (Otterbein and Choi, 2000) and HO-1 serves to provide potent cytoprotective effects in in vitro and in vivo models (Otterbein and Choi 2000). Previous study reported that anthocyanins from purple sweet potato have protective effect against t-BHP-induced hepatotoxicity by HO-1 via the Akt and ERK1/2/Nrf2 signaling pathways in HepG2 cells (Hwang et al., 2011). We isolated microsome from cells, and these microsome were analyzed for HO-1 activity by measurement of their bilirubin. As shown in Fig. 3, HO-1 enzyme activity of t-BHP-treated group was declined by 21.4% compared to control group, and chebulic acid-treated group inclined HO-1 enzyme activity. Especially, 10 μM chebulic acid significantly improved by 1.4-fold compared to t-BHP-treated group. As a result, chebulic acid significantly increases HO-1 enzyme activity and protects cells from oxidative stress.

Fig. 3.

Effects of chebulic acid on heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) enzyme activity in t-BHP-induced HepG2 cells. Cells were pretreated with chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) for 24 h and then incubated with 700 μM t-BHP for 1 h. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of 3 experiments with triplicate samples and different letters in a raw indicate statistical significance of differences among each group at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s test

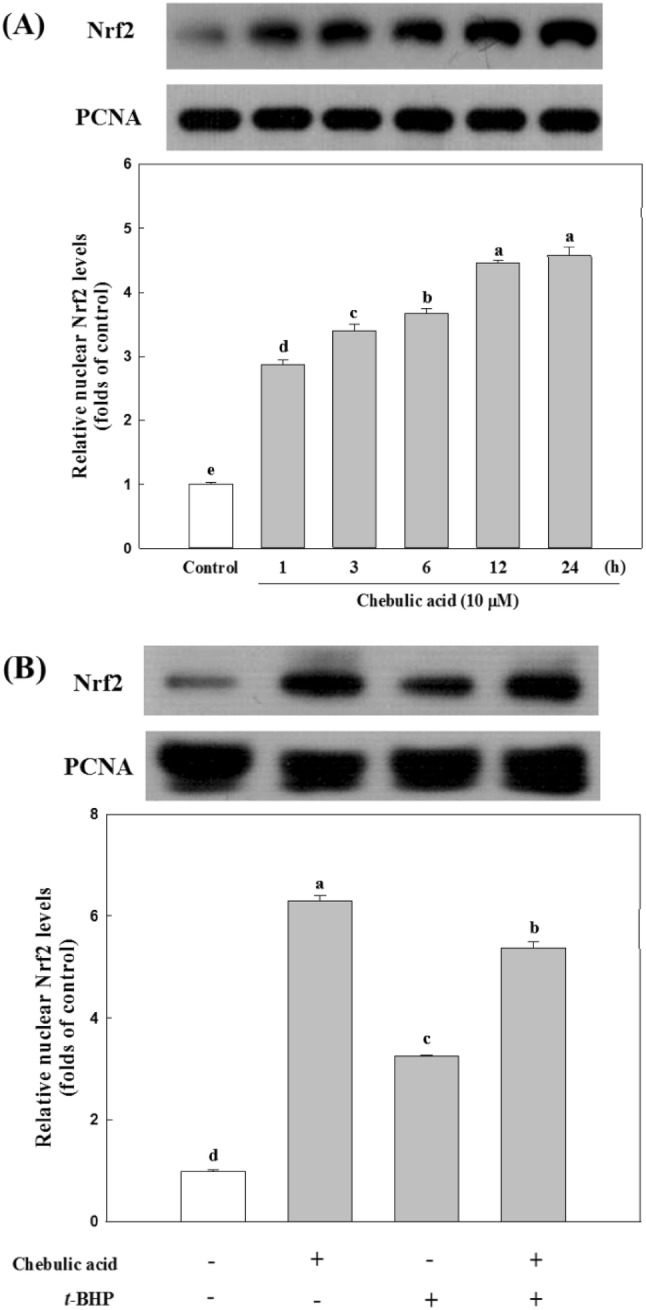

Effects of chebulic acid on nuclear Nrf2 expression

To observe the mechanism of that the treatment with chebulic acid reduced t-BHP-induced hepatotoxicity, we examined effects of chebulic acid on Nrf2 activation and its down regulated enzymes. Nrf2, a basic leucine zipper binds to ARE leading to coordinate induction of many stress-responsive or cytoprotective enzymes and related proteins (Chen and Kong, 2004). Nrf2 activation can be achieved by some inducers such as electrophiles, pro-oxidants, and chemo-preventive compounds which directly bind to Keap1 through covalent linkages and modify cysteine residue of Keap1. This interaction can cause conformational change of Keap1 and facilitate the dissociation of Nrf2 from Nrf2-Keap1 complex, which result in allowing Nrf2 to translocate into the nucleus (Hong et al., 2005). In addition, several protein kinases such as MAPK (Hu and Yuan, 2006), phosphatidylionositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt (Cuadrado and Rojo, 2008), protein kinase C (Huang et al., 2000) and casein kinase-2 (Apopa et al., 2008) have been considered to induce Nrf2 phosphorylation followed by subsequent translocation of Nrf2 into nucleus. Yang et al. (2014) showed that isorhamnetin from Oenanthe javanica protected hepatocytes against t-BHP-induced oxidative stress by Nrf2 activation, and Nrf2 deficiency blocked the ability of isorhamnetin to protect cells from injury by t-BHP. We confirmed that treatment with chebulic acid activates the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 in HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with 10 μM chebulic acid for time period (1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h). As shown in Fig. 4A, chebulic acid treatment gradually upregulated the Nrf2 expression in the nucleus of HepG2 cells. We also inspected whether treatment of chebulic acid affects the Nrf2 nuclear translocation in t-BHP-induced HepG2 cells. t-BHP increased Nrf2 expression of nucleus by 3.2 folds, and both treatment of chebulic acid and co-treatment with t-BHP significantly increased the Nrf2 expression by 6.3 and 5.4 folds compared to control group, respectively (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that chebulic acid significantly enhanced Nrf2 expression in nucleus than t-BHP-treated group suggesting that chebulic acid may have the capability to fortify cellular antioxidant activity by activating of Nrf2.

Fig. 4.

Effects of chebulic acid on the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) in nuclear protein. (A) Cells were incubated with chebulic acid (10 μM) for the indicated period (1-24 h). Nrf2 protein was detected by western blot. (B) Cells were incubated with or without chebulic acid (10 μM) and t-BHP (700 μM). Data represent the mean ± S.D. of 3 experiments with triplicate samples and different letters indicate statistical significance of differences among each group at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s test

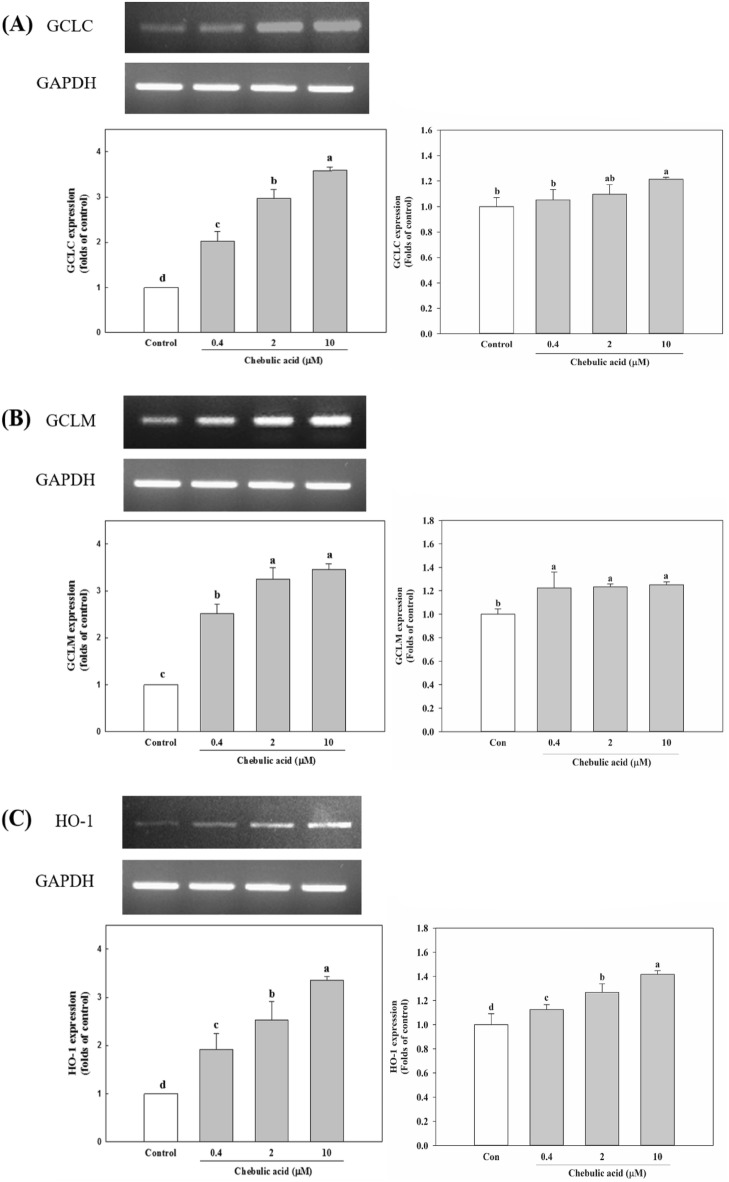

Effects of chebulic acid on expression of GCLM, GCLC, and HO-1 mRNA in HepG2 cells

γ-GCL is rate-limiting enzyme for GSH biosynthesis and is made up of a modulatory light subunit (GCLM) and a catalytic heavy subunit (GCLC). Its expression is mainly regulated by the Nrf2 (Wild et al., 1998). HO-1 is also a well-known target gene of Nrf2 and has been shown to protect phagocytes from oxidative stress associated with free iron (Willis et al., 1996). As shown in Fig. 5A, pretreatment with chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) increased GCLC mRNA expression compared to control in both RT-PCR and qPCR. And GCLM mRNA expression also increased compared to control (Fig. 5B). In addition, chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) increased HO-1 mRNA expression compared to control (Fig. 5C). In this study, the treatment of chebulic acid enhanced the mRNA expression of GCLC and GCLM, and this result may explain GSH content increased by chebulic acid.

Fig. 5.

Effects of chebulic acid on the mRNA expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM), and HO-1 by RT-PCR and qPCR in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were incubated with the chebulic acid (0.4, 2, and 10 μM) for 6 h. (A) The effects of chebulic acid on HO-1, GCLC and GCLM induction in HepG2 cells using RT-PCR (left panel) and qRT-PCR (right panel), (B) represents relative HO-1 mRNA level. (C) represents relative GCLC mRNA level. (D) represents relative GCLM mRNA level. These levels are normalized by expression of GAPDH. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 experiments with triplicate samples and different letters in a raw indicate statistical significance of differences among each group at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s test

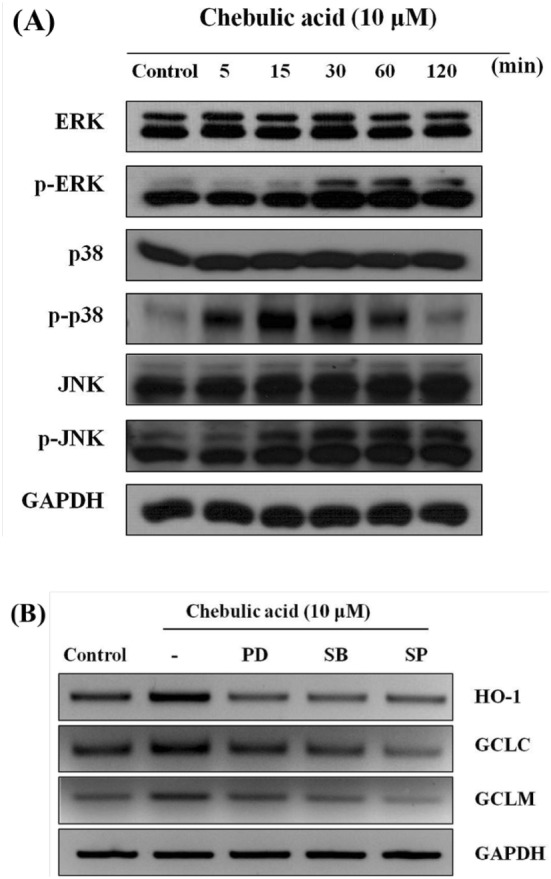

Effect of chebulic acid on expression of MAPK in HepG2 cells

MAPK are important cellular signaling molecules that convert various extracellular signals into intracellular responses by serial phosphorylation cascades and ERK, JNK, and p38 have been identified in mammalian cells (Kyriakis and Avruch, 1996). Once the MAPKs including ERK, JNK, and p38 are activated, it leads to the activation of transcription factors such as Nrf2 and ARE-mediated gene expression which enhanced metabolism of the xenobiotics and/or generated ROS, resulting in a homeostatic cell survival response (Kong et al., 2001). We examined the effect of chebulic acid on phosphorylation of MAPK. As shown in Fig. 6A, the exposure of chebulic acid resulted in increase in the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and p38. In addition, we used specific inhibitors of p38 (SB203580), JNK (SP600125) and ERK (PD98059). Theses chemical inhibitors blocked MAPK in HepG2 cells and suppressed the induction of γ-GCL and HO-1 by chebulic acid (Fig. 6B). Specific inhibitors of ERK, JNK, and p38 also inhibited the mRNA expression of HO-1 and γ-GCL. We found that chebulic acid increases phosphorylation of MAPK and protects against oxidative stress induced by t-BHP by regulating the activation of Nrf2 and its related cytoprotective enzymes such as HO-1 and γ-GCL.

Fig. 6.

Effect of chebulic acid on the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) in HepG2 cells. (A) Western blot analyses for ERK, p38 and JNK phosphorylation were conducted on cell lysates that had been incubated 10 μM chebulic acid for the indicated period (5-120 min). (B) Cells were incubated with 10 μM chebulic acid for 6 h with or without 10 μM PD98059 (ERK inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK inhibitor). Results were confirmed in 3 replicate experiments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Korea University Grant (K1617111). The authors also thank the Institute of Biomedical Science and Food Safety, CJ-Korea University Food Safety Hall (Seoul, South Korea) for providing the equipment and facilities.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that are no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahn M-J, Kim CY, Lee JS, Kim TG, Kim SH, Lee C-K, Lee B-B, Shin C-G, Huh H, Kim J. Inhibition of HIV-1 integrase by galloyl glucoses from Terminalia chebula and flavonol glycoside gallates from Euphorbia pekinensis. Planta Med. 2002;68:457–459. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apopa PL, He X, Ma Q. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 in the transcription activation domain by casein kinase 2 (CK2) is critical for the nuclear translocation and transcription activation function of Nrf2 in IMR-32 neuroblastoma cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2008;22:63–76. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains JS, Shaw CA. Neurodegenerative disorders in humans: the role of glutathione in oxidative stress-mediated neuronal death. Brain Res. Rev. 1997;25:335–358. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Kong A-NT. Dietary chemopreventive compounds and ARE/EpRE signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36:1505–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HY, Lin TC, Yu KH, Yang CM, Lin CC. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of Terminalia chebula. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003;26:1331–1335. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Rojo AI. Heme oxygenase-1 as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases and brain infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:429–442. doi: 10.2174/138161208783597407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong F, Freeman ML, Liebler DC. Identification of sensor cysteines in human Keap1 modified by the cancer chemopreventive agent sulforaphane. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:1917–1926. doi: 10.1021/tx0502138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Yuan HM. Time-dependent sensitivity analysis of biological networks: Coupled MAPK and PI3K signal transduction pathways. J. Phys. Chem A. 2006;110:5361–5370. doi: 10.1021/jp0561975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H-C, Nguyen T, Pickett CB. Regulation of the antioxidant response element by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of NF-E2-related factor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:12475–12480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220418997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang YP, Choi JH, Choi JM, Chung YC, Jeong HG. Protective mechanisms of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49:2081–2089. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Grover I, Singh M, Kaur S. Antimutagenicity of hydrolyzable tannins from Terminalia chebula in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 1998;419:169–179. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(98)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A-NT, Owuor E, Yu R, Hebbar V, Chen C, Hu R, Mandlekar S. Induction of xenobiotic enzymes by the map kinase pathway and the antioxidant or electrophile response element (ARE/EpRE). Drug Metab. Rev. 33: 255–271 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kovacic P, Jacintho JD. Mechanisms of carcinogenesis: Focus on oxidative stress and electron transfer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001;8:773–796. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Sounding the alarm: protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:24313–24316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Jung SH, Yun BS, Lee KW. Isolation of chebulic acid from Terminalia chebula Retz. and its antioxidant effect in isolated rat hepatocytes. Arch. Toxicol. 2007;81:211–218. doi: 10.1007/s00204-006-0139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Shebib AR, Wang H, Korthuis RJ, Durante W. Activation of AMPK stimulates heme oxygenase-1 gene expression and human endothelial cell survival. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;300:H84–H93. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00749.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malekzadeh F, Ehsanifar H, Shahamat M, Levin M, Colwell R. Antibacterial activity of black myrobalan (Terminalia chebula Retz) against Helicobacter pylori. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2001;18:85–88. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(01)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon M, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Chanas SA, Henderson CJ, McLellan LI, Wolf CR, Cavin C, Hayes JD. The cap ‘n’ collar basic leucine zipper transcription factor Nrf2 (NF-E2 p45-related factor 2) controls both constitutive and inducible expression of intestinal detoxification and glutathione biosynthetic enzymes. Can. Res. 2001;61:3299–3307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;582:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriel P. Role of free radicals in liver diseases. Hepatol. Int. 2009;3:526–536. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Yang CS, Pickett CB. The pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating Nrf2 activation in response to chemical stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37:433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase: colors of defense against cellular stress. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2000;279:L1029–L1037. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry LM, Metzger J. Medicinal plants of east and southeast Asia: attributed properties and uses. MIT press. 80–81 (1980)

- Rojo AI. Sagarra MRd, Cuadrado A. GSK-3β down-regulates the transcription factor Nrf2 after oxidant damage: relevance to exposure of neuronal cells to oxidative stress. J. Neurochem. 2008;105:192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabu M, Kuttan R. Anti-diabetic activity of medicinal plants and its relationship with their antioxidant property. J Ethnoparmacol. 2002;81:155–160. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00034-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem A, Husheem M, Härkönen P, Pihlaja K. Inhibition of cancer cell growth by crude extract and the phenolics of Terminalia chebula retz. fruit. J Ethnoparmacol. 81: 327–336 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Surh YJ, Kundu JK, Na HK. Nrf2 as a master redox switch in turning on the cellular signaling involved in the induction of cytoprotective genes by some chemopreventive phytochemicals. Planta Med. 2008;74:1526–1539. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonshak A, Barazani O, Sathiyamoorthy P, Shalev R, Vardy D, Golan-Goldhirsh A. Screening South Indian medicinal plants for antifungal activity against cutaneous pathogens. Phytother Res. 2003;17:1123–1125. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild A. GIPP J, Mulcahy T. Overlapping antioxidant response element and PMA responseelement sequences mediate basal and β-naphthoflavone-induced expression of the human γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase catalytic subunit gene. Biochem. J. 1998;332:373–381. doi: 10.1042/bj3320373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D, Moore A, Frederick R, Willoughby D. Heme oxygenase: a novel target for the modulation of inflammatory response. Nat. Med. 1996;2:87–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Shin BY, Han JY, Kim MG, Wi JE, Kim YW, Cho IJ, Kim SC, Shin SM, Ki SH. Isorhamnetin protects against oxidative stress by activating Nrf2 and inducing the expression of its target genes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014;274:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S-Y, Kang JH, Seomun Y, Lee K-W. Caffeic acid induces glutathione synthesis through JNK/AP-1-mediated γ-glutamylcysteine ligase catalytic subunit induction in HepG2 and primary hepatocytes. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015;24:1845–1852. doi: 10.1007/s10068-015-0241-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S-Y, Lee S, Pyo MC, Jeon H, Kim Y, Lee K-W. Improved physicochemical properties and hepatic protection of Maillard reaction products derived from fish protein hydrolysates and ribose. Food Chem. 2017;221:1979–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipper LM, Mulcahy RT. Erk activation is required for Nrf2 nuclear localization during pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate induction of glutamate cysteine ligase modulatory gene expression in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2003;73:124–134. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]