Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effects of phospholipid composition on the properties and bioavailability of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes using cell culture. Two mixtures of phospholipids with different proportions of phosphatidylcholine (PC, 23% and 70%) were used at various concentrations (0.8, 1.6, and 2.0% w/v) to prepare astaxanthin-loaded liposomes, which were investigated for entrapment efficiency (EE), antioxidant activity, morphology and changes in astaxanthin properties during a storage period of 8 weeks at 4 °C. Furthermore, Caco-2 human colon adenocarcinoma cells were employed to examine the cellular uptake of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes. The highest EE was observed with astaxanthin-loaded liposomes containing 70% PC, and used at the concentration of 2.0% w/v. Liposomes maintained the antioxidant activity of astaxanthin. All liposomal preparations were non-toxic. Cellular uptake of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes containing 70% PC was significantly higher than that of 23% PC-containing liposomes (p < 0.05).

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, Bioavailability, Encapsulation, Natural products, Shrimp

Introduction

Shrimp export in the form of frozen, chilled and cooked products has resulted in a substantial amount of revenue and made Thailand one of the major producers in the global market. Shrimp production reached 212,625.01 ton in 2017, of which approximately 40–50% of the weight is accounted for by the heads, tails, and shells that are discarded as waste or sold for animal feed in areas where Pacific white shrimps (Litopenaeus vannamei) represent the main species. Recovery of biomolecules from by-products is important for the industry to create added economic value, as is the case with abundant, naturally occurring substances such as carotenoids, which are present in crustaceans and salmonids.

Astaxanthin, a predominant pigment of the xanthophyll family, is contained in crustacean byproducts, as well as in other natural sources including microalgae and yeast. Although this pigment has long been utilized as a feed ingredient to obtain a reddish-orange color, it also supports growth and reproduction of cultured fish and other aquaculture species (Higuera-Ciapara et al., 2006). Astaxanthin as shows efficient antioxidant activity, 10 times that of other carotenoids, including β-carotene, and 100 times higher than that of α-tocopherol. This property, due to the ability of its conjugated double-bonded structure to delocalize the unpaired electrons (Naguib, 2000), has drawn major research interest in astaxanthin, which has subsequently been found to be potentially beneficial against many diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular conditions, immune system disorders and inflammation. Astaxanthin is currently available as a dietary supplement in various forms such as soft gel, tablet, oil and capsules (Ambati et al., 2014). However, owing to its chemical structure, consisting of a polyene chain joined by two terminal rings, astaxanthin is very lipophilic, resulting in low oral bioavailability, and is susceptible to degradation during processing or storage, therefore its use is restricted (Kidd, 2011). Various attempts have been made to maintain astaxanthin stability during storage and to improve its bioavailability (Anarjan et al., 2012; Tachaprutinun et al., 2009). Liposomes are one of the most commonly used encapsulation systems, first introduced as a drug-delivery vehicle and later used widely by the food industry to aid entrapment and release of bioactive compounds, as well as targetability (Mozafari et al., 2008). Liposomes are receiving much attention because of their biocompatibility, biodegradability, absence of toxicity, and high versatility due to their amphiphilic properties. Although liposome-based delivery may be scaled up for industrial applications, leakage of bioactive cargo is still one of the major drawbacks, due to the high flexibility and frailty of the bilayer membranes (Fathi et al., 2012). It is known that liposomal encapsulation can increase solubilization of astaxanthin in aqueous solution as, under these conditions, astaxanthin penetrates through the membrane of liposomes, and its terminal rings interact with the polar head groups of membranes by hydrogen bonding (Hama et al., 2012). Applications of liposomes in food industry, as a mean to protect bioactive agents, have been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Maherani et al., 2011). Studies addressing carotenoid bioavailability have been conducted using both animal and human models. A simple and inexpensive approach to evaluate bioavailability is the use of intestinal cell cultures, such as Caco-2 cells, to mimic the in vivo intestinal absorption of carotenoids. Caco-2 are human colonic adenocarcinoma cells which, upon differentiation, show similarities to erythrocytes (Sy et al., 2012). Different studies have used carotenoids either in food matrices, supplements, or pure forms. However, little is known about liposomal encapsulation and delivery of astaxanthin into cells.

In this work, we compared the effects of two different phospholipid compositions and of their concentration on the properties of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes. Moreover, changes in these properties during 8 weeks of storage at 4 °C were evaluated. Furthermore, the cellular uptake of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes by Caco-2 cells was investigated to assess astaxanthin bioavailability.

Materials and methods

Materials

Fresh shells of white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) were collected from a frozen shrimp processing plant in Samut-Sakorn province, Thailand, placed in a cool-styrofoam box and transported to the fishery products laboratory at Kasetsart University within 2 hours. Soybean lecithin (phospholipid) with 70% phosphatidylcholine (70% PC, Lipoid®P75) was acquired from Lipoid GmbH (Ludwigshafen, Germany) whereas soybean lecithin (Phospholipid) with 23% phosphatidylcholine (23% PC, Ultralec®F) was supplied by ADM (Decature, IL, USA). The pure astaxanthin (> 95%) was purchased from Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH (Augsburg, Germany). Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin were obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). HPLC-grade methanol, water, acetonitrile and dichloromethane were purchased from RCI Labscan (Bangkok, Thailand). The remaining chemicals used in the study were analytical grade.

Extraction of astaxanthin from shrimp shells and analysis

Astaxanthin from shrimp shell waste was extracted using ethanol as described by Taksima et al. (2015). In brief, 500 g of shrimp shells were mixed with 1000 mL ethanol in a blender and filtered to collect the extract. The process was done in triplicate. Solvent was removed with a rotary evaporator to get the resultant concentrate which was then analyzed for astaxanthin content by reverse phase HPLC. The Agilent 1200 series HPLC system (Santa Clara, CA, USA) used a quarternary pump, UV–visible detector and 5 μm reverse-phase C18 column (ZORBAX-Eclipse Plus, 150 mm × 4.6 mm) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The injection volume was 20 μL using an isocratic mobile phase composed of methanol: water: acetonitrile: dichloromethane (85:5:5:5, v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Chromatography was performed at 25 °C with 25 min running time and detection wavelength 480 nm. Astaxanthin was identified by its retention times against pure astaxanthin standard. Astaxanthin content was calculated based on the standard curve taking into account the mean ± SD of three sequential injections per sample.

Preparation of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes

Liposomes were prepared using the thin-film hydration method as described by Pintea et al. (2005), with slight modifications. Two types of phospholipid from soybean with phosphatidylcholine (PC) 23% and 70%, each had three different concentrations (0.8, 1.6 and 2.0% w/v) were used. In brief, the phospholipid was dissolved in ethanol, then crude astaxanthin (0.8 g) was added. After dissolution, the sample was evaporated under vacuum at 40 °C (Büchi R-124; Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawill, Switzerland). The residual lipid film was hydrated with 50 mL of water. The liposomal dispersions were subsequently prepared using ultrasonic atomization (Sonics VCX-134-FJS; Sonics & Materials, Newtown, CT, USA) at an amplitude of 80. The final sample preparations were stored in the refrigerator (at 4 °C) until use.

Determination of entrapment efficiency

The entrapment efficiency (EE) of the encapsulated astaxanthin in liposomes was measured using a modified method as described by Liu et al. (2013). In brief, samples were centrifuged at 1960 g for 10 min, and then the supernatant and residues were collected. The quantity of astaxanthin was measured by HPLC as previously described. EE (%) was calculated following the Eq. (1)

| 1 |

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activity

The antioxidant activity of astaxanthin and the astaxanthin-loaded liposomes was measured based on the scavenging activity of the stable DPPH free radical according to the method described by Duan et al. (2006) with modification. In the assay, sample (200 µL) was added to 200 µL of 0.1 mmol/L DPPH in 95% methanol. The solution was incubated in darkness for 30 min. Absorbance of the sample after incubation was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader (PowerWave XS2, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). The percentage of DPPH scavenging activity was calculated using the Eq. (2)

| 2 |

where Asample, Asample blank and Acontrol are the absorbance of the astaxanthin solution with DPPH and astaxanthin solution without DPPH and DPPH solution in methanol, respectively.

Ferrous metal ion chelating activity

The chelating effect on ferrous metal was determined using the method of Dinis et al. (1994), with slight modifications. One hundred µL of astaxanthin in methanol solution was mixed with 370 µL methanol and 100 µL ferrous chloride (2 mmol/L). To this mixture, 200 µL of ferrozine (5 mmol/L) was added. The resulting mixture was shaken and left to stand in darkness for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance of the sample solution was measured with a microplate reader (PowerWave XS2, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) at 562 nm. Percentage of chelating effect was calculated following the Eq. (3)

| 3 |

where Acontrol, Asample and Asample blank are the absorbance of mixture solution (ferrous chloride, methanol and ferrozine), astaxanthin with the mixture solution, and astaxanthin without the mixture solution, respectively.

Particle size and morphology of liposomes

Particle size of liposomes was measured by dynamic light scattering using a mastersizer (Malvern Instrument Ltd., Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). Mean size reported as volume-weighted mean diameter (d43) was obtained from three measurements. The shape of the liposome was examined by transmission electron microscope (TEM; Hitachi HT7700, Tokyo, Japan). The liposome was diluted 10 times in deionized water. The diluted liposome was put on Formvar-carbon coated copper grid then uranyl acetate was applied. The prepared grid was observed using TEM operated at 80 kV to obtain the images.

Cell culture

Human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines, Caco-2, were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), and maintained in culture medium composed of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 4.5 mg/mL glucose, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 U/mL streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM glutamine, and 1% non-essential amino acids. Cells were cultured in 75 cm2 flasks at 37 °C at 95% relative humidity, in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Exponentially growing cells were used for all assays. The final concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) used for dissolving samples was not more than 0.1%.

Cellular uptake of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes using Caco-2 monolayers

Cellular viability

The toxicity of astaxantin-loaded liposomes was determined by cell proliferation WST-1 assay, used to detect metabolic activity of cells. Caco-2 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates for 24 h. Cells were treated with 5, 10 and 20 μg/mL of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes for 24 and 48 h. Ten microliters of WST-1 was then added to the culture media, and cells and reagent were incubated for 1 h in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 environment. The viable cell number is directly proportional to the production of formazan, which was measured at 440 nm using a microplate reader (TECAN, Sunrise, Austria). Cell viability of Caco-2 was expressed in terms of the percentage viability of treated cells compared to the untreated control.

Trans-epithelial transport model

Cells between passages 5 and 10 were seeded on transwell inserts (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 1.5 × 105 cells/insert, along with 0.5 mL of growth medium in the apical side and 1.5 mL in the basolateral side. Cells were grown and differentiated to produce confluent monolayers for 21 days. The integrity of the cell monolayer was tested for trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEERS) values with Millicell-ERS equipment. A monolayer with a TEER value more than 300 Ωcm2 was used for the trans-epithelial transport experiments. Prior to transport experiments, culture media was replaced by Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) which contained 10 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid solution (MES) adjusted to a pH of 6.0–6.5 in the apical side, and HBSS containing N-[2 hydroxyethyl] piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulfonic acid] buffer solution (1 M) (HEPES) at pH 7.4 in the basolateral side. This created a pH gradient similar to that found in the small intestine. The incubation buffer was then removed from both sides of the monolayer. Liposomes loaded with astaxanthin were dissolved in DMSO and diluted with HBSS prior to loading into the apical side, while 1.5 mL of HBSS was added to the basolateral side. After incubation, an aliquot was collected from each side of the membrane. Caco-2 cell monolayers were collected by scraping into 1 mL of HBSS. Cell samples were extracted twice with hexane–ethanol–acetone in the proportion of 50:25:25, by volume. Samples were centrifuged at 706 g for 5 min and then the supernatant was removed. The remaining residues were reconstituted in mobile phase and the astaxanthin was quantified by reverse phase HPLC.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate, at a minimum. Data were submitted to analysis of variance (F-test) and then by Duncan test at a significance level of 5%.

Results and discussion

Yield of extract and concentration of astaxanthin

The ethanolic extract in an orange-red thick paste resulted in a yield of 20.39 ± 1.02 mg extract/g of shrimp shells. The results were similar to those of Taksima et al. (2015), who reported a yield of 24.66 ± 2.91 mg extract/g of shrimp shells. The concentration of astaxanthin found in the extract was 9.0 ± 0.27 mg astaxanthin/g of extract, which was higher than that obtained by Franco-Zavaleta et al. (2010), who reported a concentration of 3.866 mg astaxanthin/g of shrimp heads.

Entrapment efficiency of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes

The entrapment efficiency (EE) was used to measure the proportion of astaxanthin encapsulated within liposomes. EE was analyzed after centrifugation and the results are shown in Table 1. The initial EE (measured immediately upon encapsulation, day 0) was higher for liposomes containing 70% PC than for those containing 23% PC and maximal initial EE (97.13%) was observed at a liposomal concentration of 2.0% w/v. After 8 weeks of storage, EE values were significantly decreased in all conditions. However, the highest astaxanthin EE was found for liposomes prepared with 70% PC at a concentration of 2.0% w/v, which exhibited only a 14.2% reduction compared to day 0. Phospholipid mixtures containing 70% PC had a higher content of unsaturated phospholipids than mixtures containing 23% PC, and this may have resulted in higher EE. This would be consistent with the results of Sebaaly et al. (2015), who reported that lipid bilayers made from unsaturated Lipoid S100 were less densely packed and more flexible than those made from saturated Phospholipon 80H and 90H, and this led to higher incorporation of eugenol. The obtained EE values suggest that, after 8 weeks of storage, liposomes still retain a significant amount of astaxanthin.

Table 1.

Entrapment efficiency (%) of astaxanthin in liposomes prepared from different types and concentrations of phospholipid during 8 weeks of storage at 4 °C

| Phospholipid | Concentration of phospholipid (g/100 mL) | Entrapment efficiency (%EE) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8 | ||

| PC 23% | 0.8 | 91.67 ± 0.44Ca | 89.04 ± 1.62Db | 85.03 ± 0.69DEc | 83.78 ± 0.93Dd | 59.73 ± 0.72Ee | 43.19 ± 0.82Ef | 40.80 ± 0.73Fg | 37.36 ± 1.02Fh | 36.02 ± 0.66Fi |

| 1.6 | 87.38 ± 0.37 Da | 86.98 ± 1.81Fa | 84.76 ± 0.81Eb | 83.45 ± 0.85Dc | 64.53 ± 0.98Dd | 49.96 ± 0.47De | 47.85 ± 0.72Ef | 44.82 ± 0.58Eg | 43.64 ± 0.73Eh | |

| 2.0 | 91.42 ± 0.78Ca | 88.49 ± 0.88Eb | 85.49 ± 1.72Dc | 84.35 ± 1.02Cd | 66.21 ± 0.81Ce | 52.34 ± 0.43Cf | 50.33 ± 1.24Dg | 47.45 ± 1.14Dh | 46.32 ± 1.09Di | |

| PC 70% | 0.8 | 93.20 ± 0.16Ba | 92.74 ± 0.04Bb | 92.06 ± 0.09Bc | 90.17 ± 0.07Bd | 87.88 ± 0.33Be | 82.40 ± 0.74Bf | 73.55 ± 0.73Cg | 70.80 ± 0.37Ch | 69.67 ± 0.51 Ci |

| 1.6 | 93.05 ± 0.28Ba | 91.98 ± 0.04Cb | 91.26 ± 0.17Cc | 90.06 ± 0.13Bd | 88.22 ± 0.74Be | 82.89 ± 0.82Bf | 74.29 ± 0.64Bg | 71.62 ± 0.19Bh | 70.51 ± 0.16Bi | |

| 2.0 | 97.13 ± 0.14Aa | 95.79 ± 0.14Ab | 95.25 ± 0.07Ac | 92.63 ± 0.27Ad | 91.32 ± 0.77Ae | 90.31 ± 0.27Af | 85.44 ± 0.55Ag | 83.93 ± 0.45Ah | 83.30 ± 0.68Ai | |

Different upper-case letters within a column indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between type and concentration of phospholipid

Different lower-case letters within a row indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences during storage period

DPPH radical-scavenging activity of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes

Astaxanthin has been shown to have considerable radical scavenging activity, as assessed by DPPH assays (Roy et al., 2010). We measured astaxanthin DPPH-scavenging activity, with and without liposome-incorporation, as a measure of its antioxidant activity (Table 2). DPPH-scavenging activity of liposome-embedded astaxanthin was relatively high at day 0, reaching 81.76%. This result was in accordance with Sowmya and Sachindra (2012), who reported that carotenoids extracted from shrimp processing discards display antioxidant activity. All preparations of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes displayed comparable initial DPPH-scavenging activity (81.76%). However, liposome incorporation of astaxanthin resulted in more efficient DPPH scavenging compared to the control (astaxanthin without liposome incorporation) after storage. After 8 weeks of storage, control scavenging activity decreased from 81.76 to 19.06% (a 76.7% reduction), whereas that of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes decreased by less than 50%. The highest residual DPPH scavenging activity was associated with astaxanthin-loaded liposomes containing 70% PC and employed at a concentration of 2.0% w/v, which resulted in a 35.6% reduction compared to day 0. The results are consistent with the reported ability of astaxanthin to scavenge free radical chains through the donation of hydrogen atoms (Kidd, 2011).

Table 2.

Scavenging effect on DPPH of astaxanthin in liposomes prepared from different types and concentrations of phospholipid during 8 weeks of storage at 4 °C

| Phospho lipid | Concentration of phospholipid (g/100 mL) | Scavenging effect on DPPH (%inhibition) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8 | ||

| PC 23% | 0.8 | 77.29 ± 0.09Ea | 71.49 ± 0.37Eb | 63.44 ± 0.39Ec | 58.63 ± 0.08Ed | 56.34 ± 0.17De | 52.74 ± 0.28Ef | 50.48 ± 0.37Eg | 46.57 ± 0.22Eh | 43.35 ± 0.27Di |

| 1.6 | 73.97 ± 0.69Fa | 65.17 ± 0.22Fb | 56.68 ± 0.47Fc | 52.78 ± 0.22Fd | 49.54 ± 0.25Ee | 45.82 ± 0.35Ff | 42.39 ± 0.42Fg | 38.11 ± 0.46Fh | 37.03 ± 0.34Ei | |

| 2.0 | 80.88 ± 0.53Ca | 76.43 ± 0.62Cb | 64.82 ± 0.51Dc | 60.11 ± 0.16Dd | 56.82 ± 0.34De | 54.66 ± 0.53Df | 51.23 ± 0.52Dg | 47.92 ± 0.32Dh | 45.58 ± 0.26 Ci | |

| PC 70% | 0.8 | 80.43 ± 1.31Ca | 79.50 ± 0.50Bb | 76.81 ± 1.19Bc | 75.87 ± 0.33Ad | 71.77 ± 0.22Ae | 67.42 ± 0.36Af | 64.68 ± 0.27Ag | 59.42 ± 0.06Ah | 53.27 ± 0.07Ai |

| 1.6 | 78.51 ± 0.81 Da | 75.38 ± 2.62Db | 72.32 ± 1.27Cc | 68.62 ± 1.80Cd | 64.98 ± 0.51Ce | 57.43 ± 0.00Cf | 55.26 ± 0.09Cg | 51.67 ± 0.03Ch | 51.17 ± 0.35Bi | |

| 2.0 | 83.06 ± 1.61Aa | 81.92 ± 0.91Ab | 78.51 ± 0.63Ac | 73.72 ± 1.16Bd | 69.59 ± 0.29Be | 62.43 ± 0.09Bf | 58.32 ± 0.14Bg | 56.70 ± 0.21Bh | 53.49 ± 0.51Ai | |

| Astaxanthin extract | – | 81.76 ± 0.23Ba | 48.35 ± 0.21 Gb | 42.15 ± 0.18Gc | 38.74 ± 0.56Gd | 30.16 ± 0.66Fe | 24.43 ± 0.29Gf | 22.63 ± 0.42Gg | 22.06 ± 0.14Gh | 19.06 ± 0.37Fi |

Different upper-case letters within a column indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between type and concentration of phospholipid

Different lower-case letters within a row indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences during storage period

Ferrous metal ion chelating activity

The efficiency of astaxanthin to chelate metal ions, expressed as a percentage of the overall chelating activity, is shown in Table 3. The initial chelating activity (day 0) of the astaxanthin extract was 56.27%. Maximal initial chelating activity (63.26%) was observed with astaxanthin-loaded liposomes containing 70% PC, at a concentration of 2.0% w/v. Chelating activity continuously decreased during the 8 weeks of storage in all samples. At the end of the storage, the chelating activity of the extract had dropped to 24.82%, resulting in a 55.9% reduction, whereas that of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes decreased by less than 45%. Again, astaxanthin-loaded liposomes containing 70% PC, used at 2.0% w/v, exhibited the maximal chelating activity throughout the storage period. However, even under these conditions, chelating activity was less than 41%. Sowmya et al. (2011) also reported that the carotenoprotein isolated from shrimp head displayed antioxidant activity due to its metal chelating and DPPH radical scavenging activities.

Table 3.

Chelating effect on FIC of astaxanthin in liposomes prepared from different types and concentrations of phospholipid during 8 weeks of storage at 4 °C

| Phospholipid | Concentration of phospholipid (g/100 mL) | Chelating effect on FIC (%chelating) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8 | ||

| PC 23% | 0.8 | 48.73 ± 0.21Da | 40.15 ± 0.22Eb | 39.37 ± 0.27Ec | 38.03 ± 0.41Ed | 37.24 ± 0.44De | 34.31 ± 0.24Df | 32.29 ± 0.52Dg | 30.42 ± 0.51Dh | 29.11 ± 0.21Di |

| 1.6 | 43.11 ± 0.42Fa | 38.83 ± 0.16Fb | 35.62 ± 0.51Fc | 33.18 ± 0.70Fd | 32.08 ± 0.52Ee | 30.09 ± 0.67Ff | 28.65 ± 0.33Eg | 27.15 ± 0.58Fh | 27.73 ± 0.08Ei | |

| 2.0 | 57.11 ± 0.60Ba | 56.19 ± 0.23Ab | 53.38 ± 0.62Ac | 50.41 ± 0.41Ad | 48.15 ± 0.41Ae | 45.62 ± 0.71Af | 44.11 ± 0.28Ag | 42.36 ± 0.51Bh | 39.23 ± 0.15Bi | |

| PC 70% | 0.8 | 56.24 ± 0.12Ca | 52.63 ± 0.99Cb | 49.16 ± 0.42Cc | 48.51 ± 0.41Cd | 46.23 ± 0.41Be | 44.15 ± 0.51Bf | 42.74 ± 0.51Bg | 39.51 ± 0.21Ch | 37.18 ± 0.53 Ci |

| 1.6 | 46.79 ± 0.74Ea | 35.36 ± 0.33 Gb | 34.54 ± 0.35Gc | 33.60 ± 0.22Fd | 32.34 ± 0.55Ee | 31.09 ± 0.62Ef | 29.16 ± 0.33Eg | 27.85 ± 0.62Eh | 26.14 ± 0.38Fi | |

| 2.0 | 63.26 ± 0.49Aa | 55.30 ± 1.32Bb | 51.51 ± 0.37Bc | 49.74 ± 0.57Bd | 46.46 ± 0.32Be | 44.19 ± 0.43Bf | 43.84 ± 0.32Ag | 43.04 ± 0.31Ah | 40.01 ± 0.32Ai | |

| Astaxanthin extract | – | 56.27 ± 0.37Ca | 47.39 ± 0.29Db | 44.61 ± 0.26Dc | 39.27 ± 0.52Dd | 38.24 ± 0.44Ce | 37.63 ± 0.42Cf | 33.52 ± 0.36Cg | 27.16 ± 0.19Fh | 24.82 ± 0.47Gi |

Different upper-case letters within a column indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between type and concentration of phospholipid

Different lower-case letters within a row indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences during storage time

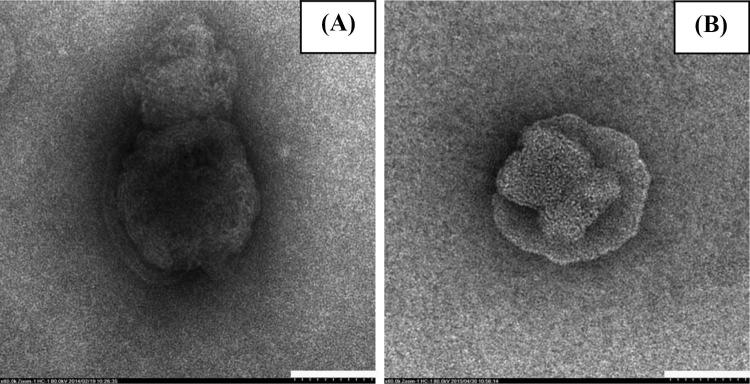

Morphological characteristics of liposomes

The TEM images of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes showed the formation of micrometer-sized structures with spherical shape. Figure 1(A, B) are representative images of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes prepared from phospholipid with 23% PC and 70% PC, respectively, both at a concentration of 2.0% w/v. Similar morphological features were described by Kim et al. (2012), showing TEM images of nanoemulsions of hydrogenated lecithin containing astaxanthin displaying square-pyramidal forms with a spherical structure. Anarjan et al. (2011) studied the cellular uptake (HT-29) of astaxanthin loaded in nanodispersions, which was prepared with different organic phases. The optimal formulation showed relatively well-defined, but polydisperse, quasi-spherical-shaped particles. In the study of Tachaprutinun et al. (2009), TEM images of astaxanthin-encapsulated PCPLC nanospheres revealed dark patches distributed within the nanospheres.

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscope images of liposomes (scale bar is 100 nm, 60,000 ×): (A) liposome made from phospholipid (23% PC) concentration at 2.0 g/100 mL, (B) liposome made from phospholipid (70% PC) concentration at 2.0 g/100 mL

Cell viability in cells exposed to astaxanthin-loaded liposomes

Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay in Caco-2 cells to verify possible cytotoxic effects of the astaxanthin extract and astaxanthin-loaded liposomes. In fact, sized-related cytotoxic effects of liposomes have been previously reported (Andar et al., 2014). The viability of Caco-2 cells exposed to both astaxanthin extract and liposomes was higher than 80%, indicating the absence of major cytotoxic effects. Similar results were obtained with astaxanthin-treated HuH7, PON1-HuH7, and HepG2 cells (Cheeveewattanagul et al., 2010; Dose et al., 2016). Conversely, concentration-dependent toxicity of astaxanthin-tween 80 complex and astaxanthin-loaded methyl β-cyclodextrin was observed (Cheeveewattanagul et al., 2010). Ribeiro et al. (2006) measured the uptake by Caco-2 and HT-29 of astaxanthin and lycopene in oil-in-water emulsions prepared with a variety of emulsifiers: sucrose laurate, Tween 20, whey protein isolate, and hydrolyzed whey protein isolate. The authors concluded that the presence of whey proteins yielded a significant increase of astaxanthin and lycopene cellular uptake and no toxicity was observed.

Cellular uptake of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes

In vitro methods based on the transport of molecules across Caco-2 monolayers are extensively used to investigate intestinal permeability in humans. These cells form confluent and differentiated monolayers with microvilli, tight junctions and transport systems, mimicking the intestine (Shah et al., 2006). Table 4 illustrates the cellular uptake of astaxanthin-loaded liposomes by Caco-2 cells. Liposomes containing 70% PC were imported with considerably higher efficiency than those containing 23% PC. Maximal uptake (95.33%) was observed with the 70% PC-containing liposomes at the concentration of 2.0% w/v, whereas 23% PC-containing liposomes did not exhibit significant cellular uptake.

Table 4.

Astaxanthin uptake in Caco-2 cells

| Phospholipid | Concentration of phospholipid (g/100 mL) | Particle size (d43) | Astaxanthin content in Caco-2 (µg/mL) | % Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC 23% | 0.8 | 0.14 ± 0.06b | 0.009 | 37.34e |

| 1.6 | 0.13 ± 0.00b | 0.017 | 70.53d | |

| 2.0 | 0.31 ± 0.00a | N.D. | – | |

| PC 70% | 0.8 | 0.17 ± 0.00b | 0.039 | 83.51c |

| 1.6 | 0.15 ± 0.00b | 0.041 | 85.06b | |

| 2.0 | 0.14 ± 0.01b | 0.049 | 95.33a |

Different lower-case letters within a column indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between types and concentrations of phospholipid

N.D., not detected

One possible explanation for these results is that 70% PC-containing liposomes are electrically neutral. Notably, Immordino et al. (2006) showed that negatively charged liposomes have a shorter half-life in the blood, compared to neutral liposomes, and that positively charged liposomes are toxic and thus quickly removed from circulation. Kälin et al. (2004) suggested that bulk PC translocate from outer membrane into inner membrane of fibroblast cells therefore, liposomes containing higher PC content could enter the inner membrane more than those containing lower PC content as indicated by our finding that a higher astaxanthin uptake was found in liposomes with PC 70% than that with PC 23%. Notably, liposomal size is another major factor potentially affecting the efficiency of cellular uptake. Of note, the size of our 70% PC-containing liposomes was around 0.14 µm, whereas the 23% PC liposomes, poorly uptaken by cells, were around 0.31 µm. A size-related effect has also been described by Kamaiko et al. (2015), who reported that emulsions with a high PC content produce the smallest initial mean droplet size. However, in that study, the largest droplet size was observed for the emulsion with the second highest PC content. Therefore, PC content may not be the only factor influencing size.

Our results are also consistent with Neves et al. (2016), who reported that liposomes with sizes below 0.20 µm, as well as their lipophilic nature, make them suitable for permeation across the intestinal barrier. Moreover, liposomal capsular materials adhere to membranes and penetrate the cells by virtue of their lipophilicity (Peng et al., 2010). Furthermore, Anarjan et al. (2012) suggested that the large surface area of small particles may allow for efficient digestion and easier absorption. Finally, Rieux et al. (2007) reported that liposomes with sizes between 0.1 and 0.2 µm are more suitable for oral absorption.

Our data suggest that the bioavailability of astaxanthin entrapped into liposomes is strongly dependent on both the intrinsic properties of PC and the size of the liposomes.

In conclusion, astaxanthin loaded liposomes made from phospholipids with different proportion of phosphatidylcholine (PC) at various concentration were assessed for properties and bioavailability. A high concentration of PC (70%) at 2% (w/v) resulted in astaxanthin-loaded liposomes with higher entrapment efficiency and higher cellular uptake than those of PC (23%) while maintaining potent antioxidant activity of astaxanthin. Cytotoxicity of liposomal preparation was not found.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Center for Advanced Studies for Agriculture and Food, Kasetsart University under the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand; Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute and also Cerebos Awards for financial support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ambati RR, Phang SM, Ravi S, Aswathanarayana RG. Astaxanthin: sources, extraction, stability, biological activities and its commercial applications-a review. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:128–152. doi: 10.3390/md12010128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anarjan N, Tan CP, Ling TC, Lye KL, Malmiri HJ, Nehdi IA, Cheah YK, Mirhosseini H, Baharin BS. Effect of organic-phase solvents on physicochemical properties and cellular uptake of astaxanthin nanodispersions. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2011;59:8733–8741. doi: 10.1021/jf201314u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anarjan N, Tan CP, Nehdi IA, Ling TC. Colloidal astaxanthin: preparation, characterisation and bioavailability evaluation. Food Chem. 2012;135:1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andar AU, Hood RR, Vreeland WN, DeVoe DL, Swaan PW. Microfluidic preparation of liposomes to determine particle size influence on cellular uptake mechanisms. Pharm. Res. 2014;31:401–413. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeveewattanagul N, Jirasripongpun K, Jirakanjanakit N, Wattanakaroon W. Carrier design for astaxanthin delivery. Adv. Mat. Res. 2010;93:202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dinis TCP, Madeira VMC, Almeida LM. Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate and 5-aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;315(1):161–169. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dose J, Matsugo S, Yokokawa H, Koshida Y, Okazaki S, Seidel U, Eggersdorfer M, Rimbach G, Esatbeyoglu T. Free radical scavenging and cellularantioxidant properties of astaxanthin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan XJ, Zhang WW, Li XM, Wang BG. Evaluation of antioxidant property of extract and fractions obtained from a red alga. Polysiphonia urceolata. Food Chem. 2006;95:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fathi M, Mozafari MR, Mohebbi M. Nanoencapsulation of food ingredients using lipid based delivery systems. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2012;23:3–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2011.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Zavaleta ME, Jiménez-Pichardo R, Tomasini-Campocosio A, Guerrero-Legarreta I. Astaxanthin extraction from shrimp wastes and its stability in 2 model systems. J. Food Sci. 2010;75:C394–C399. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama S, Uenishi S, Yamada A, Ohgita T, Tsuchiya H, Yammashita E, Kogure K. Scavenging of hydroxyl radicals in aqueous solution by astaxanthin encapsulated in liposomes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012;35(12):2238–2242. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuera-Ciapara I, Félix-Valenzuela L, Goycoolea FM. Astaxanthin: a review of its chemistry and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006;46:185–196. doi: 10.1080/10408690590957188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2006;1(3):297–315. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kälin N, Fernanades J, Hrafnsdóttir S, Meer GV. Natural phosphatidylcholine is actively translocated across the plasma membrane to the surface of mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33228–33236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaiko J, Sastrossubroto A, McClements DJM. Formation of oil-in-water emulsions from natural emulsifiers using spontaneous emulsifications: sunflower phospholipids. J. Agri. Food Chem. 2015;63:10078–10088. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd P. Astaxanthin, cell membrane nutrient with diverse clinical benefits and anti-aging potential. Altern. Med. Rev. 2011;16:355–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DM, Hyun SS, Yun P, Lee CH, Byun SY. Identification of an emulsifier and conditions for preparing stable nanoemulsions containing the antioxidant astaxanthin. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2012;34:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2011.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Ye A, Liu W, Liu C, Singh H. Stability during in vitro digestion of lactoferrin-loaded liposomes prepared from milk fat globule membrane-derived phospholipids. J. Dairy Sci. 2013;96:2061–2070. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maherani B, Arab-Tehrany E, Mozafari MR, Gaiani C, Linder M. Liposomes: a review of manufacturing techniques and targeting strategies. Curr. Nanosci. 2011;7:436–452. doi: 10.2174/157341311795542453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari MR, Johnson C, Hatziantoniou S, Demetzos C. Nanoliposomes and their applications in food nanotechnology. J. Liposome Res. 2008;18:309–327. doi: 10.1080/08982100802465941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib YMA. Antioxidant activities of astaxanthin and related carotenoids. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2000;48:1150–1154. doi: 10.1021/jf991106k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AR, Queiroz JF, Lima SAC, Tueiredo F, Fernandes R, Reis S. Cellular uptake and transcytosis of lipid-based nanoparticles acrossthe intestinal barrier: Relevance for oral drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;463:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CH, Chang CH, Peng RY, Chyau CC. Improved membrane transport of astaxanthine by liposomal encapsulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2010;5:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintea A, Diehl HA, Momeu C, Aberle L, Socaciu C. Incorporation of carotenoid esters into liposomes. Biophys. Chem. 2005;118:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro HS, Guerrero JMM, Briviba K, Rechkemmer G, Schuchmann HP, Schubert H. Cellular uptake of carotenoid-loaded oil-in-water emulsions incolon carcinoma cells in vitro. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2006;54:9366–9369. doi: 10.1021/jf062409z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieux A, Fievez V, Momtaz M, Detrembleur C, Alonso-Sande M, Gelder JV, Cauvin A, Schneider YJ, Préat V. Helodermin-loaded nanoparticles: characterization and transport across an in vitro model of the follicle-associated epithelium. J. Control Release. 2007;118:294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MK, Koide M, Rao TP, Okubo T, Ogasawara Y, Juneja LR. ORAC and DPPH assay comparison to assess antioxidant capacity of tea infusion: relationship between total polyphenol and individual catechin content. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010;61:109–124. doi: 10.3109/09637480903292601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaaly C, Jraij A, Fessi H, Charcosset C, Greige-Gerges H. Preparation and characterization of clove essential oil-loaded liposomes. Food Chem. 2015;178:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P, Jogani V, Bagchi T, Misra A. Role of Caco-2 cell monolayers in prediction of intestinal drug absorption. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006;22:186–198. doi: 10.1021/bp050208u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowmya R, Rathinaraj K, Sachindra NM. An autolytic process for recovery of antioxidant activity rich carotenoprotein from shrimp heads. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011;13:918–927. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowmya R, Sachindra NM. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of carotenoid extract from shrimp processing byproducts by in vitro assays and in membrane model system. Food Chem. 2012;134:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sy C, Gleize B, Dangles O, Landrier J-F, Veyrat CC, Borel P. Effects of physicochemical properties of carotenoids on their bioaccessibility, intestinal cell uptake, and blood and tissue concentrations. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012;56:1385–1397. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachaprutinun A, Udomsup T, Luadthong C, Wanichwecharungruang S. Preventing the thermal degradation of astaxanthin through nanoencapsulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2009;374:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taksima T, Limpawattana M, Klaypradit W. Astaxanthin encapsulated in beads using ultrasonic atomizer and application in yogurt as evaluated by consumer sensory profile. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015;62:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]