Abstract

Nicotine and alcohol addiction are leading causes of preventable death worldwide and continue to constitute a huge socio-economic burden. Both nicotine and alcohol perturb the brain’s mesocorticolimbic system. Dopamine (DA) neurons projecting from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to multiple downstream structures, including the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the amygdala (AMG), are highly involved in the maintenance of healthy brain function. VTA DA neurons play a crucial role in associative learning and reinforcement. Nicotine and alcohol usurp these functions, promoting reinforcement of drug-taking behaviors. In this review, we will first describe how nicotine and alcohol individually affect VTA DA neurons by examining how drug exposure alters the heterogeneous VTA microcircuit and network-wide projections. We will also examine how coadministration or previous exposure to nicotine or alcohol may augment the reinforcing effects of the other. Additionally, this review briefly summarizes the role of VTA DA neurons in nicotine, alcohol and their synergistic effects in reinforcement and also addresses the remaining questions related to the circuit-function specificity of the dopaminergic system in mediating nicotine/alcohol reinforcement and comorbidity.

Keywords: VTA, dopamine, nicotine, alcohol, reinforcement, electrophysiology, heterogeneity, circuit

Graphical Abstract

Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) dopamine (DA) neurons project to multiple brain areas, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala (AMG) and nucleus accumbens (NAc). Nicotine and alcohol induce heterogeneous reinforcing effects across the VTA. Anatomical location of DA neurons within the VTA dictates sensitivity and response to nicotine (+/−) or to alcohol (+/+) across the anterior/posterior and medial/lateral axes.

Introduction

Nicotine and alcohol use disorders (AUD) are both leading causes of preventable death in developed countries; causing 9 million deaths worldwide. World Health Reports (2013 and 2014) state an economic burden estimated over 4% of the European GDP (EC report) and a cost of over $300 billion in the United States for tobacco addiction and $250 billion for AUD (Sacks et al., 2015). Multiple surveys and studies depict a strong association between nicotine and alcohol abuse; consumption of one promotes the other (Bobo & Husten, 2000; Grant et al., 2004). Social aspects, genetic vulnerabilities, and neurobiological factors all contribute to nicotine and alcohol consumption.

Numerous theories and models have been generated to determine how substance abuse can induce maladaptive behaviors, drug seeking, and addiction (Everitt & Robbins, 2005; Koob & Volkow, 2016). Nonetheless, the neuronal substrates and primary mechanisms leading the transition from recreational to abusive drug use and relapse have yet to be solidified. A common hypothesis states that several steps are involved during the transition from drug use to dependence, including initial primary reinforcing effects (Koob & Volkow, 2010; Piazza & Deroche-Gamonet, 2013). Reinforcement is a process promoting a reiterative behavior during a particular context or in response to cue presentation. Drugs of abuse, including nicotine and alcohol, are suggested to hijack this function and consequently increase the repetition of behavior associated with drug intake.

Numerous brain areas are involved in the reinforcement processes. The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a brain region known to encode reward, novelty, and aversion (Schultz, 1997; Brischoux et al., 2009; Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010)). VTA dopamine (DA) neurons target multiple brain areas, including the nucleus accumbens (NAc), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and amygdala (AMG). A large majority of drugs, including nicotine and alcohol, activate this mesolimbic system and increase DA concentration in the NAc (Di Chiara & Imperato 1985; Imperato et al., 1986; Di Chiara & Imperato 1988), a region known for encoding drug salience. In line with DA’s role in natural reinforcement, learning and motivational processes, electrical and optogenetic stimulation (Tye & Deisseroth, 2012) of VTA DA neurons mimics and/or promotes drug intake behaviors (Juarez et al., 2017).

In this comprehensive review, we will describe the endogenous functionality of VTA DA neurons, their heterogeneous responses to nicotine and alcohol exposure, and how VTA DA neurons encode their reinforcing properties. Finally, we will discuss the contribution of the VTA DA neurons in the comorbid use of nicotine and alcohol.

VTA dopamine neurons

DA neurons are relatively few in number, with a total of around ~600,000 in the human brain and ~45,000 in rats (German & Manaye, 1993). They are located primarily in the ventral part of the mesencephalon (Chinta & Andersen, 2005), which includes the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical pathways. The VTA is functionally and anatomically heterogeneous, mainly composed of DA, GABA and glutamate neurons (Lammel et al., 2014). Inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons account for 20–40% (Carr et al., 2000; Nair-Roberts et al., 2008; Margolis et al., 2012), glutamate neurons account for 2–3% and DA neurons account for the rest of the VTA cellular population ~60%. This phenotypic diversity can be compartmentalized into sub regions: rostral linear nucleus of the raphe, interfascicular nucleus, caudal linear nucleus, paranigral nucleus, and parabrachial pigmented nucleus (PBP) (Oades & Halliday, 1987). Based on responsivity to natural and drug stimuli, VTA subregion classification has been simplified to medial/lateral (m/l), anterior (aVTA)/posterior (pVTA), and dorsal/ventral (Mrejeru et al., 2015; Morales & Margolis 2017).

Historically, DA neurons have been characterized by broad action potentials (AP), the presence of a hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channel-mediated Ih current, low-frequency (0.5–5hz) pacemaker activity, autoinhibition by DA-activated D2 receptors or G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels, and the presence of small-conductance activated (SK) channels (Grace & Bunney, 1984; Grace & Onn, 1989; Kitai et al., 1999; Margolis et al., 2006; Liss & Roeper, 2008). While VTA DA neurons are identified by the presence of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a rate-limiting enzyme in the production of DA (Javoy-Agid et al., 1981; Berger et al., 1982), recent data challenges this classification. Single-cell labeling studies have also shown the presence of Ih may be small or nonexistent in some VTA DA neurons (Jones & Kauer, 1999; Ford et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2010; Witten et al., 2011), and others do not respond to direct application of DA (Bannon & Roth, 1983; Lammel et al., 2008). The heterogeneous response of VTA DA neurons to drugs will be expanded upon in later sections.

DA neurons display two distinct modes of firing in vivo: tonic, single-spike activity (0.5–5 hz) or phasic bursts (10–30 hz), comprising of 2–10 APs (Grace & Bunney, 1984; Hyland et al., 2002; Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006). VTA DA neurons exclusively display tonic activity in vitro, as acute slice preparation or dissociated neurons removes the influence of active synaptic inputs (Grace & Onn, 1989; Puopolo et al., 2007). The VTA DA neuron’s pattern of activity converges from intrinsic and extrinsic electrophysiological mechanisms. VTA DA neurons express a number of channels and receptors; anatomical location and heterogeneity dictates activation. Based on a compilation of recent studies (Morales & Margolis 2017) and in the scope of this review, VTA DA neurons can express a variety of potassium channels, including GIRK2 and GIRK3 (Cruz et al., 2004; Lüscher & Slesinger, 2010; Rifkin et al., 2017), but also GABABRs (Labouèbe et al., 2007; Margolis et al., 2012), D2 receptors (Lammel et al., 2008; Margolis et al., 2008b), μ-opioid and κ-opioid receptors (Margolis et al., 2008a; Kotecki et al., 2015), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and acetylcholine (ACh) receptors (Klink et al., 2001), to name a few. In vivo, VTA DA neuron’s activity is under the control of multiple brain areas. Early studies mapped VTA circuitry, showing reciprocal connections to the PFC (Thierry et al., 1976; Divac et al., 1978), NAc, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), basolateral amygdala (BLA), lateral hypothalamus (Lh), lateral habenula (LHb), locus coeruleus (LC), ventral pallidum (VP) and other sets of smaller nuclei (Phillipson, 1979). Inhibition of pallidal afferents selectively increases VTA DA population activity, while activation of the pedunculopontine (PPTg) and the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg) increases firing activity (Clements & Grant, 1990; Oakman et al., 1995; Floresco et al., 2003; Lodge & Grace, 2006). Additionally, stimulation of the PFC induces patterns of activity in the VTA which resemble natural burst events (Tong et al., 1996). Further, the VP can regulate motivation and reinforcement by providing inhibitory control over VTA DA neurons (Hjelmstad et al., 2013).

For the past few decades VTA DA neurons have been hypothesized to encode rewards, reward-associated cues, and mediate the incentive signal, which promotes reward-seeking behavior. In this context, the transition from tonic to phasic/bursting activity plays a crucial role. This transition leads to sharp DA transients within VTA brain targets, which mediates the DA role in the reinforcement learning processes (Starkweather et al., 2017; Babayan et al., 2018) and encode incentive salience signal. According to the reward prediction error (RPE) hypothesis (Schultz et al., 1997, 1998, 2002), this fast DA transient encodes the reward value and its unpredictability; the larger the value, the stronger the DA signal. Over time, the cue predicting the reward induces DA neuron activity, while the reward itself no longer activates the dopaminergic system; the reward-associated cue becomes the reinforcer. The RPE hypothesis thus stipulates that if the cue predicts the reward value, no further activation would be observed when receiving the reward (RPE = 0), while if the reward is better than expected, VTA DA neuron’s activity increases (RPE > 0). Oppositely, the absence of an expected reward or presence of a negative event is considered less beneficial than the expected reward, inducing a decrease in DA neuron activity (RPE < 0). VTA DA neurons encode the difference between past experienced behavioral outcomes and present received outcomes, thus providing informative action value and shaping incentive salience and reiteration of the reward associated behavior. In line with this hypothesis, optogenetic phasic activation of VTA DA neurons induces a strong condition place preference (Tsai et al., 2009). Further, the presence of this RPE signal in the VTA has been tested during fMRI scans in humans when monetary gains and losses were used, where an increased blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) response was detected during a positive reward prediction error (D’Ardenne et al., 2008). More specifically, DA neurons in the VTA show phasic excitation after the presentation of reward-predicting odors, and effect that can be mimicked through optogenetic manipulation of single-cells in mice (Cohen et al., 2012).

Recent advances in cell- and circuit- probing techniques reveal VTA DA circuit-function heterogeneity, which challenges the simplified reward-encoding function proposed for DA neurons. Indeed, recent studies have described VTA DA neuron’s role in encoding salient and aversive events (Ungless et al., 2004; Brischoux et al., 2009; Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010, Chaudhury et al., 2013; Pignatelli & Bonci, 2015; Juarez & Han, 2016). Interestingly cell- and circuit- mapping studies have described anatomical function specificity (Lammel et al., 2012; Chaudhury et al., 2013; Beier et al., 2015). In particular, while dorsal VTA DA neurons are inhibited by electrical shock – in agreement with the RPE hypothesis, ventral VTA DA neurons are activated (Brischoux et al., 2009). Chronic models of stress and depression in rodents also show long-term changes in VTA DA activity (Anstrom & Woodward, 2005; Valenti et al., 2011). Specifically, chronic social stress exposure generates hyperactivity of VTA DA neurons projecting to the NAc, whereas the mPFC pathway exhibited hypoactivity (Chaudhury et al., 2013). Additionally, recent studies also show differential L/M cellular expression of VMAT2, DAT and D2R within the VTA, and functional response to D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole: medial VTA being insensitive to quinpirole, when compared to the lateral VTA (Li et al., 2013). These findings illustrate the importance of investigating projection specific pathway alterations from the VTA in the context of stress and aversion.

Primary exposure to nicotine and ethanol usurps the DA system by directly increasing the DA concentration in the synaptic cleft, particularly in the NAc, inducing their reinforcing properties. As a consequence, drug-associated cues become reinforcers while nicotine and alcohol directly activate the DA system and bypasses the initially established RPE. This direct activation has been suggested to encode hedonic and/or rewarding drug value, but also creates an aberrant incentive salience for drug-associated stimuli. Multiple theories, from the opponent processes, hedonic processes, incentive salience, to the habits/flexibility unbalance have been hypothesized to model the transition from recreative to compulsive drug taking behavior. These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and overall agree on the primary drug reinforcing properties. Here, we will focus primarily on reinforcement and the VTA DA heterogeneous response of the two most commonly abused drugs, alcohol and nicotine.

Reinforcing properties of nicotine and subsequent neural alterations

While nicotine constitutes more than 40% of the tobacco alkaloids (Wonnacott et al., 2005), other molecules contribute to the reinforcing effect of tobacco. Tobacco smoke contains multiple toxic molecules and addictive or pro-addictive molecules. Amongst them, tobacco smoke contains nicotine and its derivate –i.e. nornicotine and anabasine, β-carbolines - harmane and norharmane, and other inhibitors of monoamine oxidase (IMAO) A and B (Rommelspacher et al., 1994). Harmanes stimulate LC neurons (Ruiz-Durántez et al., 2001), increase 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and DA levels in the NAc and potentiate the activation of DA neurons (Ergene & Schoener, 1993; Baum et al., 1995, 1996; Arib et al., 2010). Also, IMAOs inhibit the degradation of serotonin and catecholamines (Villégier et al., 2006). All together, they potentiate the reinforcing properties of nicotine. While it is of importance to note that tobacco smoke reinforcement results in the concomitant action of multiple molecules, we will focus on nicotine specifically.

Nicotine, the main addictive component of tobacco (Wonnacott et al., 2005; Marti et al., 2011) hijacks the endogenous acetylcholine (ACh) system and mediates its reinforcing properties by acting through nicotinic receptors (nAChRs). Activation of nAChRs leads to the entrance of cations and consecutive intracellular cascades. These receptors are ubiquitous and highly evolutionary conserved across species (Le Novère et al., 2002). The nAChRs are members of the cysteine-loop receptor family, and allosteric transmembrane proteins forming pentameric ligand-gated channels (Galzi & Changeux, 1995; Le Novère & Changeux, 1999; Lukas et al., 1999). Twelve nAChRs subunits have been cloned from neuronal tissues: 9 alpha-subunits (α2- α10) containing a cys-cys pair required for the agonist binding site (excluded α5nAChRs), and 3 beta-subunits (β2-β4) (Changeux, 2010). The remaining α1, β1, δ, γ, and ε subunits are referred to as muscular nAChRs subunits. Each subunit contains an extracellular N- and C-terminus and 4 transmembrane (TM) domains. Five nAChRs subunits constitute a functional receptor. The α subunit N-terminus forms the agonist-binding site in combination with the adjacent subunit. The association of the TM2 of each subunit forms a central pore with ion selectivity depending on the subunit combination (Miyazawa et al., 2003; Unwin, 2005; Albuquerque et al., 2009).

Agonist binding induces an allosteric conformational transition that leads to channel opening. This mechanism was initially described for hemoglobin by the Monod-Wyman-Changeux model (Monod et al., 1965) and was then generalized to nAChRs (Edelstein et al., 1996). Persistent binding desensitizes the receptor, which is then followed by closing of the channel. Agonist affinity, permeability selectivity, and activation/desensitization kinetics depend on the nAChR subunits forming the pentamere.

The nAChR subunits form various homopentameres or heteropentameres, creating a large portfolio of pharmacological and electrophysiologically distinct nAChRs throughout the brain. Of interest, the heteropentamere α4β2*nAChRs (* including non exclusively α4 and β2 nAChRs subunits) is highly sensitive to agonists –ACh and nicotine- while the homopentamere α7nAChRs has a low affinity for these agonists, a strong Ca2+ permeability, and fast kinetics of desensitization (Changeux, 2010). The α4β2*nAChRs and α7nAChRs are largely expressed throughout the brain, whereas other nicotinic subunits are present in specific brain areas (Gotti et al., 2009), including the retina (Moretti et al., 2004), the thalamus (Pauly & Collins, 1993; Heath et al., 2010), the area postrema (Funahashi et al., 2004), the habenula (Salas et al., 2009; Fowler et al., 2011; Frahm et al., 2011), the interpeduncular nuclei (IPn) (Salas et al., 2009; Harrington et al., 2016) and the DA nuclei (Le Novère et al., 1996; Klink et al., 2001; Azam et al., 2002; Champtiaux et al., 2003).

Endogenous contribution of the nicotinic modulation of VTA DA neurons

Within the VTA, nAChRs are expressed at the somatic, perisomatic and presynaptic levels of DA, GABA and glutamate neurons (Fig. 1). The precise expression and related role of VTA nAChRs is still unclear. Nonetheless, some cellular specificity has been described. The α4β2*nAChRs is the most expressed nAChR in the VTA. The majority of VTA DA neurons express α4, α5, α6, β2 and β4 subunits and half of them express α3 and α7nAChRs subunits (Fig. 1). GABA and glutamatergic neurons preferentially express β4, α7, β2 and α4 subunits (Le Novère et al., 1996; Klink et al., 2001; Azam et al., 2002, 2007; Champtiaux et al., 2003). Finally, glutamate afferents strongly express α7nAChRs, where they have been described to contribute to NMDA-dependent long-term synaptic potentiation (Mansvelder & McGehee, 2000; Mansvelder et al., 2002; Gao et al., 2010). The VTA receives endogenous cholinergic modulation from the PPTg and the LDTg (Mena-Segovia et al., 2008). Cholinergic modulation, in addition to GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission, play a crucial role in the spontaneous activity of VTA DA neurons (Faure et al., 2014). In particular, lesions of the LDTg and PPTg decrease the firing rate and the bursting activity of VTA DA neurons (Blaha et al., 1996). In anesthetized mice, deletion of the β2nAChRs subunit gene - β2KO mice (Picciotto et al., 1998) - induces a loss of VTA DA bursting activity, associated with an alteration of exploratory behavior and uncertainty processing (Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006; Avale et al., 2008; Maubourguet et al., 2008; Naudé et al., 2016). The viral re-expression of β2 nAChRs in both VTA DA and GABA neurons are required to restore spontaneous VTA DA neuron bursting activity (Maskos et al., 2005; Tolu et al., 2012). Similar approaches show the contribution of the α4 subunit in DA burst structure (i.e. Interspike Intervals, ISI) (Tolu et al., 2010). Further characterization of transgenic mouse lines has not revealed profound alteration of the spontaneous VTA DA firing activity in mice lacking α7, α5* and β4* nAChRs (Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006; Morel et al., 2014; Harrington et al., 2016), but has defined the contribution of these subunits in VTA DA neuron’s response to chronic nicotine and stress exposure.

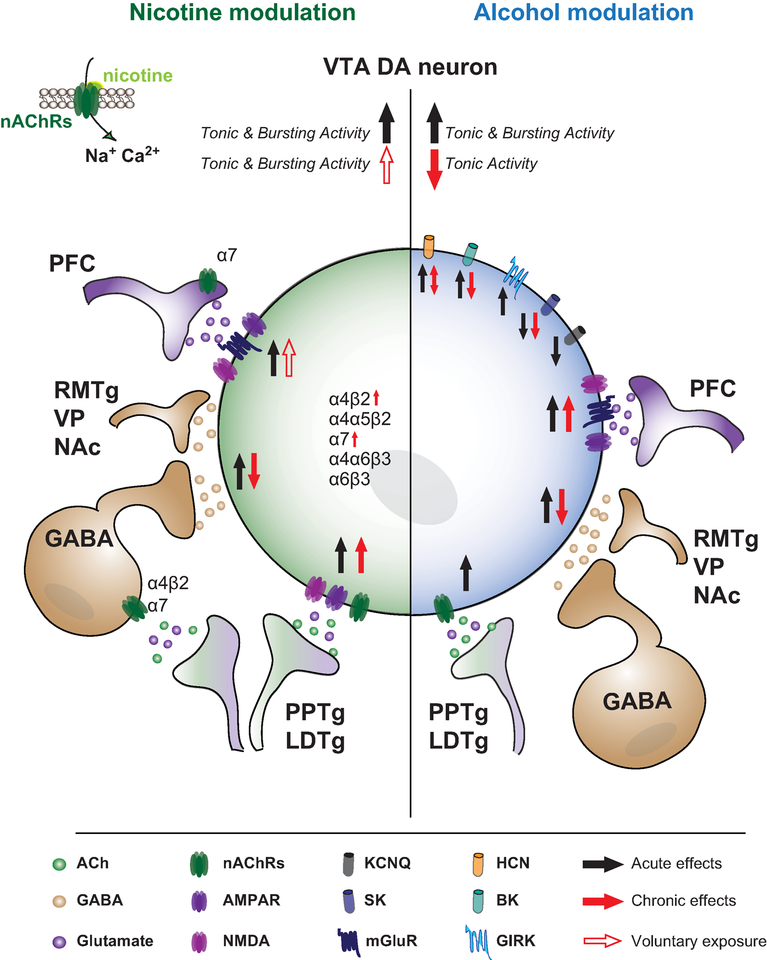

Figure 1: Schematic of the acute and chronic action of nicotine (left, green) and alcohol (right, blue) on VTA DA neurons.

VTA DA neurons receive glutamatergic inputs from: PFC, LHb, PPTg and LDTg, ACh inputs from PPTg and LDTg, and GABA inputs from local VTA GABA neurons, VP, NAc and RMTg. VTA neurons expresses a large portfolio of nAChRs (α4β2, α4α5β2, α7, α6β3, α6β4). Acute nicotine acts directly on VTA DA and GABA neurons, and potentiates the glutamatergic and GABA synaptic inputs, and overall increases the tonic and bursting activity of VTA DA neurons. Chronic nicotine exposure decreases the GABA synaptic inputs onto VTA DA neurons, and increases the expression and function of α4β2nAChRs and α7nAChRs, respectively. Voluntary chronic exposure to nicotine increases VTA DA neuron activity. Acute alcohol potentiates GABA and Glycine receptors, inhibits VTA GABA neurons, and has differing effects on K+ and HCN channels. Specifically, alcohol increases the function of HCN and BK channels, whereas SK channels are inhibited. SK channel inhibition persists after chronic exposure, and is thought to underlie increased bursting activity of VTA DA neurons in response to ethanol over time. Chronic alcohol exposure increases excitatory transmission onto VTA DA neurons, although this may be due to withdrawal effect.

Abbreviations: DA, dopamine neurons; nAChRs, nicotinic receptors; ACh, Acetylcholine; LDT, laterodorsal tegmentum, PPTg, pedonculopontine tegmentum; PFC, prefrontal cortex; Lateral habenula, LHb; RMTg, rostromedial tegmental nucleus; VP, ventral pallidum; NAc, nucleus accumbens; Big potassium channels, BK; Small-conductance activated channels; SK; Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, HCN.

Primary nicotinic modulation of VTA DA neurons

Like natural rewards, nicotine increases DA release in VTA-projecting brain areas including the NAc (Imperato et al., 1986; Ferrari et al., 2002). DA release in the NAc induced by acute nicotine exposure is due to the transition of VTA DA neurons activity from tonic to bursting and pre-synaptic nicotine-gated DA release in the NAc, which is thought to mediate the nicotine reinforcing properties.

In vitro slice electrophysiological recordings have strongly contributed to the understanding of nicotine’s mode of action onto VTA DA neurons. In voltage-clamp mode, which allows for the characterization of agonist-induced currents, ACh “puff” application induces a brief inward current. In current-clamp mode, which allows for the monitoring of APs, ACh “puff” application induces a small amount of spiking activity transiently increased and then decreased by nicotine (Pidoplichko et al., 1997). Nicotine also acts on VTA GABA neurons and inputs (Fig. 1). In voltage-clamp, while recording VTA DA neurons, nicotine induces IPSCs that are abolished by bath application of DHBE (Dihydro-B-Erythroidine hydrobromide), a competitive nicotinic ACh receptor antagonist, suggesting a β2*nAChR dependent mechanism (Mansvelder et al., 2002). The bath application of nicotine also induces excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) that are abolished in the presence of methylcaconitine (MLA), an inhibitor of α7nAChRs, but not by mecamylamine, a non-selective, non-competitive antagonist of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. These studies suggest that nicotine binds onto glutamatergic presynaptic inputs and potentiates glutamatergic transmission via α7nAChRs (Fig. 1) (Mansvelder & McGehee, 2000).

The resulting in vivo effect of nicotine observed in electrophysiological recordings is a dose-dependent increase in both firing frequency and bursting activity, which persists over several minutes (Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006; Tolu et al., 2012; Morel et al., 2014). Nicotine also synchronizes VTA DA firing activity (Li et al., 2011). Pharmacological approaches (George et al., 2011), transgenic mice, and viral strategies confirm the necessary role of the β2*nAChRs in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Indeed, the full deletion of β2*nAChRs, i.e. in β2KO mice, results in a loss of nicotine-induced VTA firing activity, and in failure to self-administer nicotine. These phenotypes are fully restored when β2nAChRs are re-expressed in the VTA (Picciotto et al., 1998; Maskos et al., 2005; Tolu et al., 2012).

VTA DA neurons have heterogeneous pharmacological and electrophysiological properties, and different modes of VTA DA neuron firing activity are observed within the same animal. In line with this heterogeneity, nicotine acts differently amongst VTA DA neurons (Fig. 1). In anesthetized mice, high bursting or firing neurons respond strongly to nicotine, with an increased tonic or bursting activity, respectively. Oppositely, low firing VTA DA neurons have a low response to the same amount of nicotine (Mameli-Engvall et al., 2006). Like many other drugs, Ach agonist intracranial self-administration (ICSA) efficiency varies across the anterior/posterior (a/p) axis (Fig. 2). Rats establish carbachol ICSA in the pVTA but not in the surrounding areas (Ikemoto & Wise, 2002). Supporting these results, the pVTA highly expresses α4, α6 and β4 nAChRs, which leads to a stronger nicotine-elicited activation of VTA DA neurons compared to aVTA DA neurons (Li et al., 2011; Zhao-Shea et al., 2011).

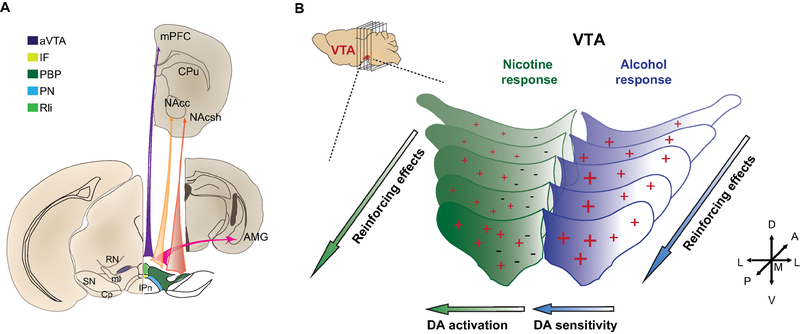

Figure 2: Dopaminergic circuit heterogeneous reinforcing effect of nicotine and alcohol.

(A) Schematic of VTA DA subnuclei and preferential projections. Recent studies using cell-specific tracing techniques established topographic preferential projection: from a medial to lateral axis, VTA DA neurons preferentially project to the mPFC, then the NAc, then the AMG and finally the NAcsh. (B) Schematic of VTA DA heterogenous neural and the consecutive behavioral response to nicotine (left, green) and alcohol (right, blue). Both nicotine and alcohol establish strong reinforcing effects when infused in the pVTA compared to the aVTA. VTA DA neurons display distinct activity in response to nicotine. Lateral VTA DA neurons are activated (+) by i.v. nicotine injection, medial VTA DA neurons are inhibited (−). VTA DA neurons have an increased sensitivity to alcohol across the medial/lateral axis (+, +).

Abbreviations: AMG, Amygdala; aVTA, anterior ventral tegmental area; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; CPu, caudate putamen; CP, cerebral peduncle; IF, interfascicular nucleus; IL, infralimbic cortex; IPn, interpeduncular nucleus; LHb, lateral habenula; mHb, medial habenula; ml, medial lemniscus; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; NAcc, nucleus accumbens core; NAcsh, nucleus accumbens shell; PBP, parabrachial pigmented nucleus; PN, paranigral nucleus; pVTA, posterior ventral tegmental area; RN, red nucleus; RLi, rostral linear nucleus; SN, substantia nigra.

In anesthetized mice, while the majority of VTA DA neurons, preferentially recorded in the PBP, are activated in response to nicotine injection, a subpopulation is inhibited. In vivo juxtacellular neurobiotin labeling techniques allow for discrete cellular mapping and confirmed the TH+ expression profile of these two subpopulations. Nicotine-activated neurons are preferentially located in the lateral part of the PBP while nicotine-inhibited VTA DA neurons are preferentially located in the medial PBP (Fig. 2). Further investigations define a D2-receptor dependent inhibition, opening the question on the role of these neurons in nicotine reinforcement (Eddine et al., 2015).

While nicotinic action onto VTA DA neurons has been well established, the primary nicotinic action onto VTA GABA neurons remains unclear. Multiple lines of evidence suggest a disinhibition of VTA GABA neurotransmission onto VTA DA neurons, thus contributing to nicotine-induced VTA DA activity (Fig. 1) (Grieder et al., 2014; Buczynski et al., 2016). This disinhibition is attributed to the desensitization properties of VTA β2*nAChRs, while in parallel, nicotine activates the α7nAChRs expressed on glutamatergic inputs, strengthening glutamate neurotransmission that leads to VTA DA activation (Mansvelder & McGehee 2000; Mansvelder et al., 2002). The latest studies on β2KO mice show that the co-activation of both VTA GABA and DA neurons by nicotine is required to induce VTA DA bursting activity in response to nicotine exposure (Tolu et al., 2012). Indeed, the sole re-expression of β2nAChRs in VTA DA neurons of β2KO mice is sufficient to nicotine-induced tonic firing of VTA DA neurons, but is not sufficient to observe bursting and the associated maintenance of nicotine self-administration. Conversely, the specific re-expression of β2nAChRs exclusively on VTA GABA neurons leads to an expected inhibitory response of VTA DA neurons to nicotine and absence of nicotine self-administration. Interestingly, dual re-expression on both VTA GABA and DA neurons is necessary to observe firing frequency and bursting activity in response to nicotine, and prolonged nicotine self-administration (Tolu et al., 2012). These results highlight the crucial role of β2nAChRs, VTA DA bursting activity in mediating the reinforcing properties of nicotine, but also the complex modulation performed by VTA GABA neurons on these processes.

Hypersensitive α4nAChRs subunit overexpression increases VTA DA neuron’s nicotine sensitivity and promotes nicotine preference (Tapper et al., 2004). Conversely, α4KO mice recapitulate the phenotype of DA cell-type specific β2 re-expression in β2KO mice: loss of nicotine induced bursting activity and nicotine self-administration (Pons et al., 2008; Exley et al., 2011). Such a profile could be due to compensatory α6β2*nAChRs functions and an imbalance between VTA DA and GABA. The precise contribution of α6*nAChRs is unclear. Rats treated with an α6*nAChRs antagonist (Gotti et al., 2010) and α6KO mice both fail to self-administer nicotine during intravenous self-administration (IVSA) (Pons et al., 2008); whereas VTA ICSA is maintained (Exley et al., 2011). Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) studies have established the crucial role of α6β2*nAChRs in NAc pre-synaptic terminals, where the α6β2nAChRs gate VTA DA signals (Exley & Cragg 2007; Exley et al. 2011; Siciliano et al., 2017). In line with these results, hypersensitive α6nAChRs expression increases DA release (Wang et al., 2014) and VTA response to nicotine (Drenan et al., 2008).

Recent interests emerged for the gene locus 15q25, which encodes for the α3, α5 and β4 nAChRs. In particular, the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs16969968 leads to a point mutation in the coding sequence of the α5*nAChRs subunits, D398N, which decreases α4α5β2nAChRs function (Bierut et al., 2008; Kuryatov et al., 2010). 398N-homozygote smokers are twice as susceptible to develop heavy tobacco addiction compared to 398D-homozygote smokers (Saccone et al., 2006). The α5*nAChRs is strongly expressed by 80% of VTA DA neurons (Klink et al., 2001) and their terminals, where this subunit preferentially forms an α4α5β2*nAChRs. The α5KO mice self-administer a higher concentration of nicotine compared to wild-type (WT) mice and have a decreased sensitivity to nicotine (Salas et al., 2003; Fowler et al. 2011; Morel et al. 2014). The VTA expression of the α5-N subunit, mimicking the human 398N mutation, is associated with VTA DA decreased sensitivity to nicotine compared to the α5-D subunit, which is causally related to higher doses of nicotine to induce acute nicotine self-administration (Morel et al., 2014).

Animal models of nicotine reinforcement

Numerous paradigms have been established to study the physiological consequences of nicotine exposure. While human pharmacokinetics or social aspects are absent, animal models offer the ability to control multiple aspects difficult to calibrate in human subjects, including: age of onset, gender, genetic profile, etc. Nicotine can be passively administered (i.e. injection, infusion, transdermal delivery, or vapor) or actively self-administered by the animal (Matta et al., 2007; Kallupi & George, 2017).

Nicotine self-administration protocols offer the ability to study the reinforcing properties of nicotine from primary reinforcing properties, to withdrawal and relapse. In these protocols, the animals perform an action associated with nicotine delivery, which mimics voluntary human drug intake. Nicotine self-administration has been established in various species including non-human primates, rats and mice (Goldberg et al., 1981; William A. Corrigall & Coen 1989; Le Foll & Goldberg 2009). Similar to opioid self-administration, nicotine self-administration dose-response curve follows an inverted U-shape. This profile may result from positive nicotine reinforcing effect –the ascending part of the curve, and the negative/aversive nicotine effects –descending part of the curve for higher dose of nicotine. Nicotine self-administration is often difficult to establish, thus, numerous paradigms include a training phase using food rewards or other drug pre-exposure and food restriction prior to nicotine self-administration (Caggiula et al., 2002; Fowler & Kenny 2011; Caille et al., 2012). This pre-exposure can induce some difficulty in fully understanding the initial mechanism of nicotine reinforcing effects, since the action leading to the nicotine intake (lever press, nose-poke, etc.) has already been positively reinforced during the training phase.

Distinct nicotine self-administration protocols illuminate different aspects of the nicotine reinforcement processes. Of interest, ICSA consists of a local nicotine infusion in discrete brain areas. ICSA studies provided the foundation for how VTA nAChRs established nicotine reinforcement (Corrigall et al., 1994). The acute IVSA paradigm performed on naïve animals offers the opportunity to detect the primary dose required to increase the propensity of an action associated with the drug delivery. For example, the paradigm used in Pons et al., the loss of nicotine reinforcing effect in β2KO, α4KO, α6KO, is described by the lack of increased nose-poke activity for the nicotine dose tested compared to WT mice (Pons et al., 2008). Nonetheless, other aspects critical to characterizing nicotine dependence require classic IVSA protocols, which assess acquisition, motivation, compulsion, and relapse (Caggiula et al., 2002; Kenny & Markou 2006; Fowler et al. 2011; Fowler & Kenny 2011; Orejarena et al. 2012).

Chronic nicotine modulation of VTA DA neurons

Long-term chronic exposure to nicotine affects multiple peripheral and cognitive functions: metabolism, immune response, memory and attention. Even though nicotine acts on the same nAChRs as endogenous ACh, chronic exposure to nicotine cannot be perceived as “hypercholinergy”. Nicotine is degraded by liver enzymes and has a longer systemic half-life (about 10–15min for rodents), whereas ACh esterase hydrolyses ACh in the synaptic cleft in milliseconds. Nicotine, compared to ACh, can thus desensitize nAChRs and be internalized by the surrounding cells. Chronic nicotine exposure induces the desensization (Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Grady et al., 2012) and the upregulation of nAChRs (Fig. 1) (Buisson & Bertrand 2001; Staley et al., 2006; Fasoli et al., 2016). These two phenomena are thought to contribute to withdrawal processes and overall nicotine addiction mechanisms. While nAChRs desensization is associated with impaired nAChRs functions and decoupling with the endogenous ACh tone (Pidoplichko et al., 1997), the nAChRs upregulation, suggested to compensate for nAChR hypofunction, increases receptor trafficking, turn over and alters endogenous nAChRs composition in the VTA (Nashmi et al., 2007; Baker et al., 2013).

The consequences of chronic nicotine exposure on VTA DA activity vary depending on the protocol used. Voluntary nicotine self-administration increases the spontaneous firing activity of VTA DA neurons both in tonic and bursting activities, whereas passive exposure via osmotic minipumps does not induce detectable effects (Besson et al. 2007; Caillé et al. 2009). Chronic nicotine exposure leads to the reorganization of VTA nAChRs and modifies their properties, uncovering the role of α7nAChRs. Indeed, in β2KO mice chronically exposed to nicotine, α7nAChRs contribute to the recovered VTA DA neuron’s firing activity (Besson et al., 2007), and restores to WT-like nicotine intake behaviors. Conversely, chronic exposure to nicotine induces a decrease in nicotine consumption in α7KO mice (Levin et al., 2009).

Taken together, VTA nAChRs mediate the reinforcing effects of nicotine differently on VTA DA, GABA and glutamate neurotransmission. The high affinity β2*nAChRs is the limiting factor, while α7nAChRs tune the system via glutamate neurotransmission. Finally, other subunits and their related polymorphisms, like α5nAChRs D398N, modulate the sensitivity of VTA DA neurons to nicotine and define the nicotine dose required to encode its reinforcing effects.

Network contributions

Nicotine acts not only on the VTA, but also on numerous brain areas contributing to the regulation of DA activity. Recent advances in circuit-probing techniques contribute to network contributions in nicotine reinforcement. The Infralimbic cortex (IL) – BNST circuit projecting on VTA (Kaufling et al. 2017; Kaufling et al. 2009), contributes to the increased spontaneous activity of VTA DA neurons (Fig. 3) following voluntary but not passive (Fig. 1), nicotine self-administration (Caillé et al., 2009). These results highlight network contributions in shaping VTA alterations during nicotine reinforcement.

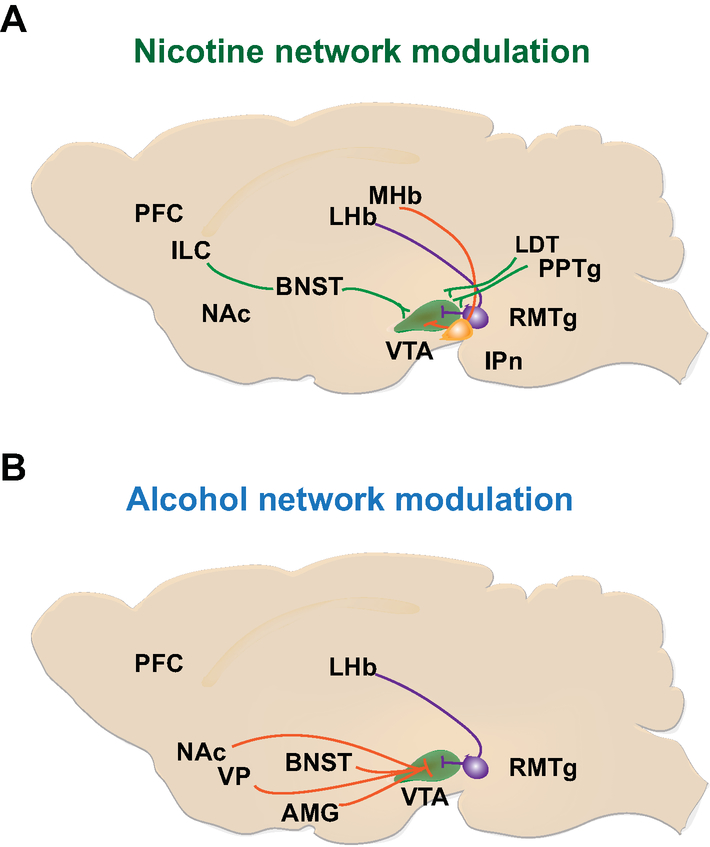

Figure 3: Network nicotine and alcohol modulation of VTA DA neurons.

(A) Network modulation onto VTA DA neurons in response to nicotine. The IL-BNST-VTA circuit (green) increases the spontaneous VTA DA activities following voluntary nicotine consumption. mHb-IPn circuit decreases the reinforcing properties of high concentration of nicotine by encoding aversive signal. The precise modulation of this pathway onto VTA DA neurons remains poorly understood. LHb-RMTg-VTA circuit requires further investigation to fully characterize its function in nicotine reinforcement. While LHb-RMTg activation inhibits VTA DA neurons, nicotine activation of RMTg neurons does not affect VTA DA neural response to nicotine. (B) Network modulation onto VTA DA neurons in response to alcohol. Activation of DA receptors in the NAcsh, VP, and PFC are involved in mediating the reinforcing effects of ethanol and inhibitory projections from the VP to the VTA may control alcohol seeking and reinstatement. The LHb-RMTg-VTA circuit has been hypothesized to contribute to aversive conditioning of ethanol response and may account for individual differences in drinking behaviors. Stress and withdrawal affects of chronic alcohol exposure are highly controlled by the connections between VTA and AMG.

Abbreviations: AMG, Amygdala; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; CPu, caudate putamen; IL, infralimbic cortex; IPn, interpeduncular nucleus; LHb, lateral habenula; mHb, medial habenula; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; NAcc, nucleus accumbens core; NAcsh, nucleus accumbens shell.

Of recent interest, the habenulo-interpeduncular (mHb-IPn) pathway has been determined as a strong modulator of nicotine reinforcing properties (Fowler et al. 2011; Ables et al. 2017). IPn neurons project to the dorsal tegmentum and the raphe nucleus (Lecourtier & Kelly, 2007; Hsu et al., 2013; Antolin-Fontes et al., 2015). The mHb sends a glutamatergic projection to the IPn and encodes negative/aversive signals. Numerous nAChRs subtypes are highly expressed in the mHb-IPn pathway (Grady et al., 2009). The α5*nAChRs in the mHb-IPn circuit, similarly to the VTA, is a sensor of nicotine concentration. Fowler and collaborators defined that α5KO mice and knockdown rats self-administered for higher doses of nicotine than WT animals. This shift to a higher dose of nicotine is not only due to a decrease in nicotine’s reinforcing effects, but also to a decrease in the nicotinic aversive signal encoded by the mHb-IPn pathway (Fig. 3). In line with these results, functional alteration of β4*nAChRs in the mHb-IPn circuit modulate nicotine self-administration and NAc DA release and VTA DA neuron’s sensitivity to nicotine effects (Harrington et al., 2016). This phenotype is recovered by selective re-expression of β4nAChRs subunits in the IPn. In parallel, over-expression of β4nAChrs in the mHb-IPn pathway increases nicotine-induced aversive responses (Frahm et al., 2011).

The recent characterization of the tail of the VTA, the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) (Sanchez-Catalan et al., 2014), contributes to the description of the LHb-RMTg-VTA circuit, also encoding for aversive signals (Perrotti et al., 2005). RMTg GABA neurons project to VTA DA neurons (Jhou et al., 2009; Kaufling et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2011) and LHb-RMTg-VTA circuit activation inhibits VTA DA neurons (Ji & Shepard 2007; P. L. Brown et al., 2017). Morphine and WIN decrease RMTg activity and thus promotes VTA DA neuron firing (Fig. 3). Unexpectedly, nicotine activation of RMTg does not elevate GABA inhibitory control over VTA DA neurons, and does not affect VTA DA neuronal activation by nicotine (Lecca et al., 2010; Lecca et al., 2012). Further investigations will be required to fully understand the contribution of the LHb-RMTg-VTA pathway in nicotine and drug reinforcement.

Alteration of non-drug functions of VTA DA neurons

Human smokers show impulsive behaviors, altered cognitive flexibility, and present a higher propensity to develop mood disorders than non-smokers. Smoking and impulsivity form a bidirectional relationship; increased impulsivity is associated with increased smoking vulnerability and increased nicotine dependence (Kale et al., 2018). A recent study described the role of VTA β2*nAChRs in uncertainty seeking behaviors (Naudé et al., 2016). Since nicotine exposure alters the endogenous function of β2*nAChRs in the VTA, it is expected that nicotine would affect uncertainty seeking processes and overall decision making (Naudé et al., 2015). Nicotine enhances the reinforcement of non-drug reinforcers both in humans (Perkins & Karelitz 2013; Perkins et al., 2018) and animals (Donny et al., 2003; Constantin & Clarke 2017). Nicotine’s ability to strengthen the reinforcing properties of non-drug reinforcers, in particular smoking-associated cues, is hypothesized to enhance primary reinforcing properties and promote nicotine intake (Caggiula et al., 2002; Donny et al., 2003; Palmatier et al., 2007; Farquhar et al., 2012).

Smoking dependence and mood disorders are highly comorbid in humans (Mathew et al., 2017). Smokers, although abstinent for several years, are threefold more likely to develop mood disorders (Breslau & Johnson, 2000); smoking as a coping strategy is highly prevalent in patients suffering from mood disorders. The role of nAChRs in mood disorders has been investigated in humans (Saricicek et al., 2012) and confirmed in animal models (Mineur et al., 2016, 2017). VTA DA neurons do not only encode positive reinforcement and reward, but also for negative and salient events, promoting adaptive behaviors. Thus, VTA DA neurons are highly involved in the maintenance of healthy brain functions and behaviors (Russo & Nestler 2013). In line with this role, alteration of VTA DA function is causally associated with depressive and anxiety-like phenotypes (Cao et al. 2010; Chaudhury et al. 2013; Barik et al. 2013; Friedman et al., 2014; Friedman et al., 2016). The stress-induced model of depression, chronic social defeat stress (CSDS), increases the spontaneous activity of VTA DA neurons projecting to the NAc, which leads to social avoidance behavior and anhedonia (Chaudhury et al., 2013) – two characteristic symptoms of depression. CSDS decreases VTA DA neuron’s nicotine-induced firing activity (Morel et al., 2017), which may decrease nicotine-reinforcing properties. This result coincides with human subjects who report an increased nicotine consumption following stressful events. Blocking β2*nAChRs in depressed mice exacerbates social avoidance behaviors, while blocking α7nAChRs rescues social interaction behaviors (Morel et al., 2017). Conversely, nicotine pre-exposure via α7nAChRs primes VTA DA maladaptations and the development of depressive phenotypes, following sub-threshold stress exposure (Morel et al., 2017). The opposite action of β2*nAChRs and α7nAChRs blockade in depressed mice requires the development of selective α7nAChRs inhibitors for further therapeutic approaches.

Reinforcing properties of ethanol and subsequent neural alterations

Ethanol is a two-carbon molecule that interacts with other biomolecules through weak hydrophobic interactions or hydrogen bonding. In addition to this, ethanol also has a low binding affinity to proteins, severely limiting its potency. The legal limit of 0.08% v/v is approximately 17mM in the human body, whereas the anesthetic concentration is 190 mM (Alifimoff et al., 1989). Upon ingestion, ethanol is ubiquitously distributed throughout total body water; the blood concentration approximates ethanol concentration in all organ and cellular compartments. Ethanol easily passes through the blood brain barrier and is known to have direct and indirect targets throughout the brain. Unlike other drugs of abuse, even low to intermediate concentrations of ethanol disrupt the normal functioning of neurotransmitter receptors, ion channels, intracellular signaling proteins (Yoshimura et al., 2006; Pany & Das, 2015; Ron & Barak, 2016; Mohamed et al., 2018), and also perturbs membrane lipids (Cui & Koob, 2017).

VTA DA neurons are a critical neural substrate for reward and ethanol reinforcement (Pfeffer & Samson, 1988; Samson et al., 1988; Nestler, 2005; Koob & Volkow, 2010). Acute exposure to ethanol facilitates VTA DA neuron’s firing both in vitro and in vivo, increases DA within the VTA (Fig. 1), as well as many downstream targets (Di Chiara and Imperato 1985; Brodie et al., 1990; Appel et al., 2003). Ethanol reinforcement was increased by microinjections of DA agonists in the NAc during a free choice operant task using 10% ethanol in rats (Hodge et al., 1992). Microdialysis studies augmented this finding by showing an increased concentration of DA in the NAc after self-administration of 10% ethanol but not saccharin (Weiss et al., 1993). Ethanol directly modulates the function of DA channels and receptors, while also manipulating extrinsic synaptic inputs onto DA neurons from within and outside of the VTA. Rats establish strong ethanol ICSA (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000), and many behavioral paradigms show escalated intake of ethanol over time (Rhodes et al., 2005; Sharpe et al., 2005; Crabbe et al., 2011), despite ethanol’s aversive taste.

The complex nature of ethanol actions in the VTA is the further compounded by age, sex, and species differences. Different murine strains exhibit different drinking preferences and responses to acute and chronic ethanol (Cunningham et al., 1992; Belknap et al., 1993; Wanat et al., 2009). This is likely due to genetic or more recently epigenetic differences underlying reward and aversion processing (You et al., 2018). Age also effects the production and turnover of DA in the VTA (Woods & Druse, 1996), which may explain varying sensitivity of VTA DA neurons to ethanol across studies. While sex differences are not covered in this review, recent evidence clearly shows differences in ethanol consumption, response to reward, and aversion between males and females and need to be studied further (You et al., 2018). Within the scope of this review, the acute and chronic effects of ethanol on DA neurons are summarized below, starting with direct modulation of intrinsic excitability and moving onto extrinsic and circuit modulations.

In this review we will focus on ethanol’s reinforcing effects on VTA DA neurons specifically and subsequent microcircuit and network alterations. For more extensive molecular and anatomical reviews on ethanol throughout the brain, please see references (Harris et al., 2008; Trudell et al., 2014; Abrahao et al., 2017).

Primary ethanol modulation of VTA DA neurons

Acute application of ethanol increases the spontaneous firing frequency of VTA DA neurons in vivo, in vitro slice preparation and dissociated cell culture in ethanol-naïve animals (Gessa et al., 1985; Brodie et al., 1990, 1999; Brodie & Appel, 1998). Ethanol excitation of VTA DA neurons occurs despite being dissociated from synaptic and glial connections (Brodie et al., 1999), or by the presence of GABA, glutamate, or ACh antagonists (Nimitvilai et al., 2016). Modulation of both direct and indirect ethanol targets all contribute to the firing and functions of VTA DA neurons.

The HCN channel-mediated Ih current is known to contribute to the pacemaker firing of DA neurons and are direct ethanol targets (Harris & Constanti, 1995; Neuhoff et al., 2002). Treatment with ZD7288, an Ih blocker, irreversibly depresses basal firing frequency of VTA DA neurons (Fig. 1) and significantly attenuates the stimulatory effect of ethanol on firing (Okamoto, 2006). This excitatory Ih current is enhanced partly by ethanol’s ability to augment cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent facilitation of voltage-gating (Okamoto, 2006). However, this effect has been shown only in mice, not in rats (Appel et al., 2003; McDaid et al., 2008). Ethanol has also been shown to directly increase barium-sensitive inhibitory potassium currents in VTA DA neurons (McDaid et al., 2008), but this effect can only decrease firing if Ih is blocked.

Ethanol also targets the M-current (Im) (Hansen et al., 2008), a sustained K + current that is activated at the subthreshold range of membrane potential, regulating AP generation (Brown & Adams, 1980; Aiken et al., 1995). In contrast to Ih, ethanol decreases Im conductance, inadvertently decreasing inhibition and increasing the spontaneous firing frequency of VTA DA neurons in vitro (Koyama et al., 2007). Kv7 channels are the principal molecular components of the slow voltage-gated M-channel (Brown & Passmore, 2009). Of recent interest, Kv7.4 channels have been shown to regulate ethanol intake and dependence (McGuier et al., 2018).

VTA DA neurons also express small conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) and Big potassium (BK) channels (Fig. 1) that are also modulated by acute ethanol (Brodie et al., 2007), and express specific subtypes in the VTA (Stocker & Pedarzani, 2000). During an AP, membrane depolarization and Ca2+ influx activate BK and SK channels, which both help to terminate the AP and produce fast after-hyperpolarization (AHP) (Faber & Sah, 2007; Lee & Cui, 2010). Interestingly, acute ethanol seems to decrease SK channel function in a heterologous expression system (Dreixler et al., 2000), while potentiating BK channel function by increasing channel open probability (Mulholland et al., 2009; Dopico et al., 2014). The amount of the SK current present may dictate the sensitivity of VTA DA neurons to ethanol excitation (Brodie et al., 1999b), but inhibition of this channel with apamin, a peptide neurotoxin form bee venom that specifically blocks SK channels, failed to strongly reduce ethanol-induced VTA DA neuron excitation. Further, preliminary studies have shown that specific subunits of the BK channels can modulate ethanol sensitivity and can also influence drinking behavior (Bettinger et al., 2014) although further studies are needed on the role of both of these channels in VTA DA mediated ethanol reinforcement.

Ethanol modulates DA neuron’s excitability via the GIRK inwardly rectifying K + channels (Fig. 1). GIRK channels contribute to the resting membrane potential of VTA DA neurons and contributes to tonic/bursting switch of pattern activity (Lalive et al., 2014). Ethanol can directly module GIRK channels or indirectly through a G-coupled protein (Kobayashi et al., 1999; Lewohl et al., 1999; Blednov et al. 2001; Beckstead et al., 2004; Labouèbe et al., 2007; Aryal et al., 2009). For instance, ethanol has been shown to potentiate GABAB receptor-induced inhibition of VTA DA neurons through the downstream activation of GIRK channels (Federici et al., 2009). GIRK3 specifically has been shown to regulate ethanol sensitivity (Herman et al., 2015), although GIRK antagonists fail to fully inhibit ethanol excitation of DA neurons in other studies (Appel et al,. 2003; McDaid et al., 2008). This may, in part, be due to the differential distribution of GIRK subunits throughout the VTA (del Burgo et al., 2008; Rifkin et al., 2017). Accordingly, acute ethanol both directly and indirectly increases the function of GIRK channels on VTA DA neurons, potentially mediating inhibitory effects known to stabilize VTA DA firing.

Ethanol (30 to 100 mM) acts also on ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) (Dildy-Mayfield et al., 1996; Mascia et al., 1996). For example, ethanol can potentiate the function of LGICs such as glycine and GABAA receptors and inhibit excitatory NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors in brain region- and concentration-dependent manner (Lovinger & Roberto, 2010; Söderpalm et al., 2017). Canonical activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors (NMDA and AMPA) on VTA DA neurons increases in vivo firing and burst activity (Fig. 1) (Johnson et al., 1992; Chergui et al., 1993; Zweifel et al., 2009). Surprisingly, increased AMPAR-mediated excitatory synaptic transmission was determined in in vitro slice electrophysiology 24h after intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection (20mg/kg) in C57BL/6J mice (Saal et al., 2003), although this may be due to the effect of acute withdrawal. In contrast, a single ethanol exposure was shown to reduce AMPA/NMDA receptor function on VTA DA neurons 24h after intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration (2g/kg) in DBA/2J but not C57BL/6J mice (Wanat et al., 2009), revealing strain-specific ethanol sensitivity. The conflict in studies may be due to concentration of ethanol used. Acute ethanol can also act presynaptically by enhancing glutamatergic transmission onto VTA DA neurons and increasing the frequency but not the amplitude of spontaneous EPSCs (Deng et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009). While it is well known that ethanol can directly inhibit excitatory NMDA-mediated currents in a variety of other neurons/preparations (Valenzuela et al., 1998; Ronald et al., 2001), it remains unclear how acute ethanol directly modulates AMPA/NMDA receptors on VTA DA neurons and how this action may or may not contribute to ethanol reinforcement.

Acute ethanol potentiates the firing of DA neurons, but has differing effects on GABA release at DA synapses and inhibitory transmission within the VTA (Fig. 1) (Burkhardt & Adermark, 2014; Abrahao et al., 2017). Approximately 20–40% of VTA neurons are GABAergic and regulate VTA DA neuron activity (Carr et al., 2000; Margolis et al., 2012). VTA GABA neuron firing recorded directly in vivo (0.2–2.0 g/kg, i.p.) has been shown to be inhibited by acute ethanol administration (Steffensen et al., 2000; Stobbs et al., 2004). D2R and μ-opioid receptors are both expressed on VTA GABA neurons. They are targets of ethanol and affect VTA GABA neuron firing- activation decreases firing and increases DA release within the VTA (Xiao et al., 2007; Ludlow et al., 2009). However, a single, acute exposure to ethanol either i.p. (2g/kg) or through bath application (50 mM) in slice showed increased GABAergic transmission and GABA release onto VTA DA neurons (Melis et al., 2002; Theile et al., 2008; Theile et al., 2011). These inhibitory effects are most likely due to long-range projections coming from outside of the VTA, whereas the aforementioned studies focus on VTA GABA neurons directly. In contrast, low dose ethanol administered i.v. (0.01–0.1 g/kg) in the rat seems to stimulate VTA GABA neuron firing (Steffensen et al., 2009). The current hypothesis states that ethanol-induced increase in DA firing activity is partially due to “disinhibiting” DA neurons by blocking inhibitory effects (Xiao et al., 2007). Further investigation is needed to clarify whether these ethanol-induced synaptic effects are coming directly from VTA GABA interneurons or unique afferent projections from other brain structures.

Lastly, ethanol potently modulates nAChRs at many concentrations (100 μM–10 mM), but is not a direct agonist (Liu et al., 2013). The specific effects of this interaction are dependent upon the subunit composition of the receptor, and will be touched upon towards the end of this review when discussing interactions between nicotine and alcohol.

While a wide range of studies has been published on the effect of ethanol on DA neurons in the VTA (see additional review by Morikawa and Morrisett, 2010), its precise effect is still obscure. Numerous discrepancies arise from differences in species, behavioral model, and concentration of ethanol administered, but also from the VTA DA subpopulation being investigated (Lammel et al., 2008, 2014; Poulin et al., 2014). The majority of VTA DA neurons send specific projections to non-overlapping targets, further solidifying the importance of cell-type and projection specific research (Fallon, 1981; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000; Lammel et al., 2008). Circuit-probing techniques highlight the different contribution of VTA DA projections in the reinforcing properties of ethanol (Fig. 2) (Juarez et al., 2017). Interestingly, medial VTA DA neurons seem more responsive to ethanol (Fig. 2) (Mrejeru et al., 2015; Avegno et al., 2016). Additionally, acute exposure to ethanol in the pVTA increases VTA DA neuron activity and decreases activity in the aVTA in conjunction with decreased and increased IPSCs (Guan et al., 2012). It also seems that the pVTA is more sensitive to the excitatory effects of ethanol; rats will self-administer via ICSA in the pVTA when compared to aVTA (Fig. 2) (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000).

Network contributions to ethanol reinforcement

Changes in the brain induced by chronic ethanol intake are long lasting and recruit an extensive network of neural circuits. The magnitude of ethanol’s impact within specific neural circuits and cells is dictated by concentration, route of administration, and exposure frequency (i.e. acute v. chronic). Therefore, it is imperative to take into account network modulations occurring throughout the brain during chronic use (Seo & Sinha, 2014; Abrahao et al., 2017). Optogenetics and novel tracing viral strategies have now made it possible to assess behaviorally relevant inputs and anatomical connectivity between brain structures and how the function and sensitivity of these circuits change in the context of drug addiction (Osakada et al. 2011; Tye & Deisseroth, 2012).

Activation of DA receptors in the NAc shell, VP, and PFC are involved in mediating the reinforcing effects of ethanol in the pVTA (Ding et al., 2015). Indeed, one study found that self-administration of ethanol continued until NAc DA concentrations were normalized after chronic use (Weiss et al., 1996). Furthermore, systemic administration of ethanol in rats leads to an increase in the frequency of phasic DA transients in the NAc detected with FSCV, supporting the idea that ethanol promotes the occurrence of DA neuron bursts (Cheer et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2009; Morikawa & Morrisett, 2010). Systemic injection of naltrexone can inhibit ethanol-induced NAc DA release associated with self-administration (Gonzales & Weiss, 1998). Neurotoxin lesioning of DA terminals in the NAc suppresses ethanol-taking behaviors as measured by two-bottle choice (2BC) or self-administration paradigms (Rassnick et al., 1993; Ikemoto et al., 1997). While both the AMG and PFC are also involved in drug seeking and decision-making, their role is less pronounced than the NAc in ethanol reinforcement (Meinhardt et al., 2013).

External projections onto VTA DA neurons have also been shown to influence ethanol related behaviors and reinforcement (Fig. 3). The ventral pallidum (VP) is a well-established structure for ethanol reinforcement and reinstatement of drug seeking and whose GABAergic neurons project directly to the VTA. Chemogenetic inactivation of the VP-VTA pathway successfully reduced alcohol seeking and reinstatement in rats (Prasad & McNally, 2016). The lateral habenula (LHb), comprised of mostly glutamatergic neurons, is also a key brain structure in modulating VTA DA neurons, specifically in the context of aversion. In rats given home cage access to 20% ethanol in an intermittent access 2BC paradigm, LHb lesioned animals escalated their voluntary ethanol consumption more rapidly than controls (Haack et al., 2014). The LHb projects directly to the VTA, but also influences VTA DA activity through the LHB-RMTg-VTA circuit. Stimulation of the LHb inhibits VTA DA neurons, potentially through the influence of RMTg inhibition and low doses of ethanol (0.25 g/kg i.p.) in rats have been shown to activate neurons in the LHb, potentially accounting for aversive conditioning and individual differences in drinking behaviors between and within animal strains (Fu et al., 2017). Many other brain areas project onto the VTA, including the PFC, NAc, BNST, and LDTg; however, their exact role in regulating VTA DA response to ethanol reinforcement needs to be studied further with cell-type and projection-specific tools.

Chronic ethanol modulation of VTA DA neurons

Over the last 50 years, researchers have used animal models of chronic ethanol exposure to determine the impact of repeated ethanol exposure on specific cells and neural circuits and more closely mimic human alcohol consumption and abuse (Becker, 2008; Leeman et al., 2010; Koob, 2014). Alcohol addiction can be conceptualized as a multi-stage cycle that involves escalating drug use and neuroplastic changes in the brain’s natural reward system over time (Koob & Volkow, 2016). Preclinical studies of chronic alcohol use elucidate the long-lasting effects of ethanol on the brain by revealing compensatory mechanisms, long-term plasticity changes and aberrant learning (Weiss & Porrino, 2002; Hyland et al., 2002). Various animal models of chronic alcohol exposure include: intermittent or 24 h access 2BC, drinking in the dark (DID), vapor chamber, chronic intermittent access (CIE), and repetitive i.p. injections (Crabbe et al., 2010). Many models of chronic ethanol exposure seek to model later phases of addiction, including drug seeking and relapse, intoxication, binge drinking and withdrawal. However, in this review we will focus on experimental studies that assess how the reinforcing properties of ethanol on VTA DA neurons change through repeated ethanol exposure.

Chronic ethanol has been shown to sensitize VTA DA neuron’s response to bath application of ethanol after chronic in vivo administration (3.5mg/kg 2× daily i.p., 21 days), with no change seen in baseline pacemaker activity (Brodie, 2002). Another group found a 25% reduction in Ih density and a subsequent reduction in the magnitude of ethanol stimulation of firing in mice in vitro (2 g/kg 1× daily i.p., 5 days) (Okamoto, 2006). This discrepancy in ethanol sensitization of VTA DA neurons may arise from length of exposure. Longer periods of alcohol exposure may induce homeostatic neuroadaptations not seen at short time intervals, but also the VTA DA neuron subpopulations investigated. Using a 10% ethanol 2BC paradigm of unlimited alcohol access, one group found that VTA-NAc DA neurons had significantly increased Ih current in low alcohol drinking mice and a significantly decreased Ih current in high alcohol drinking mice when compared to controls (Juarez et al., 2017). In contrast, in vitro recordings made from VTA DA neurons 1–6 days after cessation of chronic ethanol consumption in mice (liquid diet, ~23 days) revealed decreases in baseline firing (Bailey et al., 2001). The amount of ethanol consumed by the mice (25–32 g/kg/24 h) in this study may explain the attenuation of baseline VTA DA excitability, but also reveals profound differences in the physiological affects of ethanol on VTA DA activity based on route of administration and potential affects of withdrawal. A further complication is the disparity between passive (i.p.) and active self-administration of ethanol, although passive ethanol still can facilitate ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice (Lessov et al., 2001). In accordance with this, sensitization and tolerance of the DA system have been reported after different ethanol treatment protocols (Zapata et al., 2006; Ding et al., 2009).

Many different mechanisms may affect VTA DA neurons response to chronic ethanol and subsequent shifts in reinforcement. Microinjections of the dopamine D2/D3 agonist quinpirole in the VTA of Long-Evans rats reduced lever pressing for 10% ethanol, supporting the early hypothesis that DA activity in the VTA is involved in ethanol reinforcement (Hodge et al., 1993). The effects of D2R autoinhibition and subsequent activation of GIRK channels was studied after chronic administration of ethanol (2mg/kg i.p. 3× for 7 days). Patch-clamp recordings revealed increased activity of D(2)/GIRK-mediated inhibition whereas GABAB/GIRK mediated inhibition was not affected (Perra et al., 2011). SK channel function has also been shown to be reduced 7 days after rats are repeatedly exposed to ethanol (2g/kg i.p. 2× for 5 days) (Hopf et al., 2007). Because of this reduction in SK channel function, it has been hypothesized that this and several other alterations ultimately increase the ability of VTA neurons to produce burst firing and thus might increase ethanol reinforcement and contribute to addiction-related behaviors.

As discussed previously, there are multiple extrinsic inputs onto VTA DA neurons that regulate synaptic transmission and firing patterns- driving a form of aberrant learning and reward (Stuber et al., 2010). Chronic ethanol exposure can cause increased long-term potentiation (LTP) of NMDAR-mediated transmission in VTA DA neurons (Bernier et al., 2011), but only at very high doses of ethanol (6 g/kg/day). Chronic administration of ethanol (2–3.5 g/kg, i.p. 1–2×/day for 5–21 days) from two different groups shows no change in NMDA receptor function (Brodie, 2002; Hopf et al., 2007). Longer studies in rats, spanning up to 50 days of volitional intake, show an increase in AMPA-mediated synaptic transmission onto VTA DA neurons (Stuber et al., 2008). Lastly, it was found that only long-term exposure to ethanol increased levels of immunoreactivity of the NMDAR1 subunit, an obligatory component of NMDA receptors, and of the GluR1 subunit, a component of many AMPA receptors (Ortiz et al., 1995). As a result, the reinforcing properties of ethanol may also be partly driven by enhanced learning of both cue and reward through LTP.

Acute ethanol decreases the activity of VTA GABA neurons (Gallegos et al., 1999; Davies, 2003) and in addition, high doses of ethanol (3.5 g/kg i.p., daily for 21 days), seem to reduce the sensitivity of GABA-induced inhibition of VTA DA neuron firing (Brodie, 2002; Stobbs et al., 2004; Adermark et al., 2014; Burkhardt & Adermark, 2014). Tolerance to local ethanol inhibition by VTA GABA neurons was produced by 2 weeks of CIE/ethanol vapors (Gallegos et al., 1999), although this is less involved with reinforcement due to passive inhalation. Chronic ethanol exposure (5% liquid diet, ~2–3 weeks), has also been shown to down-regulate D2 receptors on VTA GABA neurons, potentially resulting from the persistent release of DA onto GABA neurons (Ludlow et al., 2009). It has also been reported that intra-VTA injection of a delta-opioid receptor (DOR) agonist decreases ethanol consumption in a 2BC paradigm, via presynaptic inhibition of GABA release onto VTA DA neurons (Margolis et al., 2008a). These results indicate selective adaptations after chronic ethanol exposure; excitatory transmission is perturbed to enforce the learning of reward, whereas inhibitory transmission is muted or diminished.

Ethanol has also been shown to block long-term potentiation of GABAergic synapses via μ-opioid receptors (Guan & Ye, 2010). Naltrexone, a non-selective opioid antagonist, decreases the rewarding and euphoric effects of alcohol and is one of the only current therapies for recovering alcoholics. While administration of naltrexone did not block the acute release of dopamine in the VTA of ethanol-naïve rats, it did prevent this release from being prolonged (Valenta et al., 2013), a mechanism which may modulate the rewarding effects of ethanol but only in chronic users. VTA neurons express a wide variety of opioid receptors, but specifically targeting them in the VTA to increase therapeutic efficacy has not yet been achieved. Stimulation of another ethanol target, the κ-opioid receptor, also suppresses ethanol consumption and preference in rats (Nestby et al., 1999; Lindholm et al., 2001; Logrip et al., 2009)

Effects of ethanol withdrawal and stress on VTA DA neurons

Repeated exposure to ethanol and withdrawal creates an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms controlling VTA DA neurons, and also increases the frequency of negative affect and stress- two main drivers to relapse. The main effects of alcohol withdrawal on synaptic physiology and behavior have been extensively studied in other brain regions such as the AMG and PFC (Roberto & Varodayan, 2017; Varodayan et al., 2018), including withdrawal affects on the excitability and synaptic transmission of DA neurons and impact on reinforcement.

Initially, primary exposure to ethanol increases DA release in the VTA and NAc,. Ethanol withdrawal has been shown to decrease tonic and phasic DA firing in rats (Diana et al., 1993, 1995), returning to control levels after 2 months (Bailey et al., 2001). This hypodopaminergic state is said to drive drug seeking and relapse, shifting the sensitivity of the mesolimbic DA system overall. In humans imaging studies, AUD are correlated with decreased D2 receptor availability and DA release in the striatum of alcoholics (Martinez et al., 2005; Volkow et al., 2002, 2007). Many studies have also shown a decrease in tonic DA levels in the NAc in rodents withdrawn from chronic ethanol exposure (Rossetti et al., 1992; Diana et al., 1993; Weiss et al., 1996). Contrastingly, protracted abstinence in rodents who have undergone chronic vapor exposure exhibit a hyperdopaminergic state (Hirth et al., 2016). The convergence of hypodopaminergic states during withdrawal and hyperdopaminergia at later time points may, in fact, drive the neuroadaptations seen in late-stage alcoholics. This may be due to a shift in brain stimulation reward, which has been modeled using ICSA in rats (Schulteis et al., 1995) and can be seen after exposure to many drugs of abuse.

Ethanol also stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis by acting on corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), increasing levels of this peptide throughout the brain and affecting alcohol and anxiety-related behaviors, specifically during withdrawal states (Allen et al., 2011). Recently, it has been shown that GABAA inhibition of VTA DA neurons is regulated by presynaptic actions of CRF in mice following 3 days of withdrawal from four weeks of CIE (Harlan et al., 2018). The VTA receives CRF from projecting terminals of the BNST, the central amygdala (CeA), and even from local CRF synthesizing neurons in the VTA (Korotkova et al., 2006; Rodaros et al., 2007; Grieder et al., 2014). The CeA, for example, is mostly composed of GABA neurons (Roberto et al., 2012), receives a dense VTA DA projection, and is integral to mediating fear and anxiety response (Ressler, 2010). Together, the CeA and HPA axis constitute a major player in the withdrawal phase, or negative affect state experienced by many alcoholics. CRF enhances GABAergic transmission in the CeA, potentially affecting the processing of aversive stimuli or negative emotional salience (Bajo et al., 2008; Roberto et al., 2010; Cruz et al., 2012; Koob, 2015). Projections between the AMG and VTA may regulate response to ethanol and should be further characterized and considered, especially when assessing function and sensitivity of VTA DA neurons during acute or protracted ethanol withdrawal.

Nicotine and ethanol interactions on VTA DA neurons

Tobacco and alcohol comorbidity is highly associated (World Health Reports 2013, 2014). While nicotine dependence is prevalent amongst AUD patients and is shown to promote alcohol consumption, a history of AUD increases vulnerability to develop nicotine addiction (Bobo & Husten 2000; Grant et al., 2004; Hughes et al., 2000). Multiple socio-economical and genetic factors (True et al., 1999) contribute to the development of this polyaddiction. This is also largely driven by the legality of both of these drugs. In this section we will focus on the synergistic effects of nicotine and ethanol on VTA DA function in reinforcement.

Concomitant acute injection of nicotine and ethanol increases VTA DA neurons firing both in vitro (Clark & Little, 2004) and in vivo (Tolu et al., 2017), followed by a subsequent release of DA in the NAc (Tizabi et al., 2002, 2007). Nicotine and ethanol exhibit an additive effect for “low” doses, which is blunted at higher doses. This suggests an initially synergistic but later opposing effect on common brain circuits. In line with this hypothesis, rats establish ICSA in the pVTA using a sub-reinforcing dose of nicotine and ethanol. However, systemic interactive effects diverge depending on exposure and the addiction stage observed, suggesting distinct cross-sensitization mechanisms.

Several studies have shown that pre-exposure to nicotine increases alcohol consumption (Smith et al., 1999; Tolu et al., 2017) and the acquisition of self-administration (Clark et al., 2001; Doyon et al., 2013). As previously mentioned, nicotine exposure directly alters innate VTA DA neuron functionality due to its similarity to ACh mechanism of action, but later promotes the reinforcing properties of other natural reinforces. Thus, nicotine may prime VTA DA neurons to encode the reinforcing properties of ethanol more strongly. Consequently, nicotine’s priming effect on ethanol consumption is occluded by prior exposure to nAChRs antagonists, involving the nAChRs as a substrate of nicotine-ethanol interactive effects. In line with these studies, nAChRs inhibition or genetic manipulation of nAChRs also alters ethanol consumption (Ericson et al., 1998; Blomqvist et al., 1993) and VTA DA neuron’s activity in response to alcohol (Liu et al., 2013; Tolu et al. 2017).

In addition, nicotine potentiates glutamatergic transmission (Mansvelder & McGehee 2000; Saal et al., 2003) and alters GABA modulation onto VTA DA neurons (Mansvelder et al., 2002), contributing to potential altered ethanol effects. Doyon and collaborators have established that nicotine pre-exposure blunts VTA DA neurons activation in response to alcohol, due to increased inhibitory synaptic transmission (Doyon et al., 2013). A recent longitudinal study showed that nicotine exposure during adolescence increased GABAergic inhibition of DA neurons in the lateral VTA in response to ethanol exposure and led to a long-lasting self-enhancement of alcohol self-administration in rodents (Thomas et al., 2018). Such effects are regulated by the neuroendocrine system, in particular by the stress hormone corticosterone. These results highlight the broad impact of nicotine throughout the brain, particularly since its targets are much more discrete than ethanol’s. Nicotine modulates not only VTA microcircuit function but also crucial afferents form distal brain regions, including circuits encoding aversion (i.e. LHb and mHb circuits) and stress responses (i.e. HPA axis).

The precise impact of ethanol pre-exposure on nicotine reinforcement driven by VTA DA neurons is not yet clear. Ethanol exposure alters nAChRs expression profile in the brain (Booker & Collins, 1997; Tarren et al., 2017). Ethanol also alters the endogenous function of choline acetyltransferase, suggested to lead to ACh hypofunctions (Pelham et al., 1980; Floyd et al., 1997). Ethanol pre-exposure may decrease (Korkosz et al., 2006) nicotine-induced withdrawals, but also exacerbates (Meck, 2007) nicotine effects. Rats selectively bred to develop high sensitivity to ethanol have also high sensitivity to nicotine (de Fiebre et al., 1991). Further investigation should be performed to define how previous exposure to ethanol primes or blunts nicotine’s reinforcing properties. Due to the multi-dimensional impact of ethanol, it is reasonable to hypothesize a large impact of ethanol pre-exposure on VTA DA neuron’s function in encoding nicotine-reinforcing properties; in particular, the negative/aversive effects of high nicotine doses on the VTA microcircuit and other important afferent projections.

Future directions and conclusions

In the current review, the role of VTA DA neurons in nicotine and alcohol reinforcement was discussed. Both nicotine and ethanol cause a transient increase in VTA DA neuron tonic and burst firing, and over time, alter the endogenous functions of the VTA, resulting in an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory transmission, microcircuit, and overall brain function. Further, other phases of the addiction cycle- intoxication and withdrawal- are equally important in explaining how drug use can lead to pathological states. Social aspects, other drug co-exposure and mood disorders, are not covered in this review but are also well known risk factors. Other factors known to contribute to nicotine and ethanol addiction include: sex hormones (Lenz et al., 2012), immune function (Warden et al., 2016; Roberto et al., 2017), species differences (Juarez & Han, 2016), age of exposure and development (Burke & Miczek, 2014; Smith et al., 2015), glial function (Lacagnina et al., 2017) genetics, (Walters, 2002; Liu et al., 2004; Vink et al., 2005), and most recently, epigenetics (Nestler, 2013). Sex differences are being investigated, as males and females respond differentially to most drugs of abuse (Calipari et al., 2017; Riley et al., 2018). The contribution of sex hormones to the reinforcing, and other stages, of the addiction cycle, are also currently under investigation. In parallel, the immune system shows involvement with drug-taking behaviors and withdrawal. Equal in complexity to the nervous system, the immune system and relevant immunomodulatory molecules are becoming new therapeutic targets for addiction (Blednov et al., 2017; Harris et al., 2017).