Introduction

Carcinoid tumors of the ovary are uncommon, but cases of primary and metastatic ovarian carcinoids have been reported. Primary carcinoid tumors of the ovary are divided into insular, trabecular, strumal and mucinous types [1]. The insular type is the most common, followed by the strumal type. The carcinoid tumors of ovaries are unique because they pour large amount of serotonin in systemic circulation and cause early manifestations of carcinoid syndrome and tricuspid valve disease before tumor is metastasized. In contrast, gastrointestinal carcinoid barely produces symptoms early as the hormones liberated from the tumors are inactivated in liver [2].

Right-sided heart valve dysfunction occurs due to the venous drainage of serotonin which is metabolized by the liver, and hence, carcinoid heart disease can only occur once there are liver secondaries. Ovarian carcinoids drain directly into the systemic circulation and can lead to tricuspid valve changes even without liver involvement. Correspondingly, left-sided valve dysfunction, which is usually accompanied by coronary vasospasm, may be present as the result of a patent foramen ovale found in less than 10% of individuals with carcinoid heart disease [3, 4]. Primary ovarian carcinoids metastasize only occasionally and should be treated as ovarian tumors of low malignant potential.

Case Report

A 58-year-old woman was admitted in November 2015 with complaints of occasional shortness of breath, bilateral pedal edema, occasional flushing and persistent diarrhea, progressing for the last 6 weeks. She was a known hypertensive on regular medication, but non-diabetic and euthyroid. She was menopausal with no significant gynecological complaints.

On examination, she was found to have a blood pressure of 144/80 mmHg and a pulse rate of 104 per minute, regular. She had hyperpigmentation of the face and was slightly tachypneic (28 breaths/min). Her chest was clear on auscultation, but there was a pansystolic murmur over the left lower sternal border. Her jugular venous pulse was engorged, and pulsatile and bilateral pitting edema of both feet was present. On abdominal palpation, her liver was slightly enlarged, palpable 3 cm below the right costal margin.

Her chest skiagram showed a small right-sided pleural effusion, which resulted in a dry tap. Routine hematology and biochemical panel were normal.

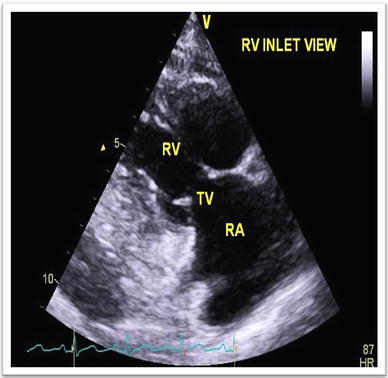

Considering the presence of features of right heart failure, an echocardiography was done (Fig. 1). It showed normal left ventricular dimension and function, but abnormal morphology of the tricuspid valve. Tricuspid stenosis was present along with severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Fig. 1.

Thickened tricuspid valve on echocardiography

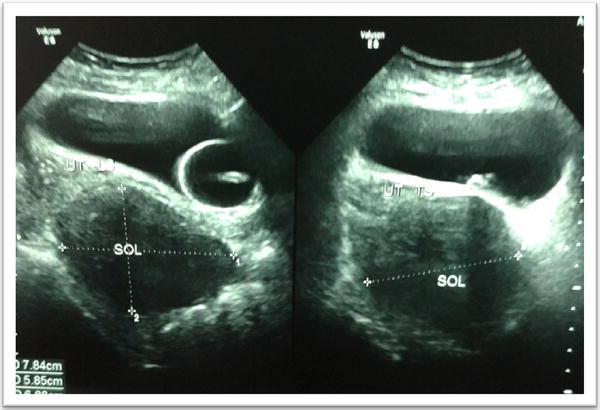

The simultaneous presence of diarrhea, flushing and isolated tricuspid valve abnormality led us to consider carcinoid syndrome with carcinoid heart disease as a probable diagnosis. We carried out analysis of urine for 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (HIAA) levels. Twenty-four-hour urine sample for 5-HIAA levels showed a substantially raised value of 186 µmol (reference range 6–10 µmol/day). Lungs and the gut are the commonest site of primary carcinoid tumors. CT thorax failed to detect any tumor. A colonoscopy with cecal biopsy was done which showed minimal chronic inflammation. On ultrasonography of the abdomen, we found a hypoechoic SOL (measuring 8.5 × 6.8 × 8.2 cm) in the pouch of Douglas with echogenic foci inside (Fig. 2). These findings were corroborated on gynecological examination.

Fig. 2.

USG lower abdomen showing the pelvic SOL

The CT abdomen showed an enhancing, nearly homogeneous solid SOL in the POD of dimensions 8 × 8 × 7 cm with well-defined margins (Fig. 3). The SOL was seen pushing both the uterus and urinary bladder anteriorly. The liver was mildly enlarged without focal lesion.

Fig. 3.

CT scan abdomen pelvis–transverse section

Exploratory laparotomy was carried out at the earliest by the department of gynecology which showed a left-sided solid cystic ovarian mass with intact capsule measuring 8 × 10 cm, impacted in the POD. A total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was done. The postoperative recovery period was uneventful.

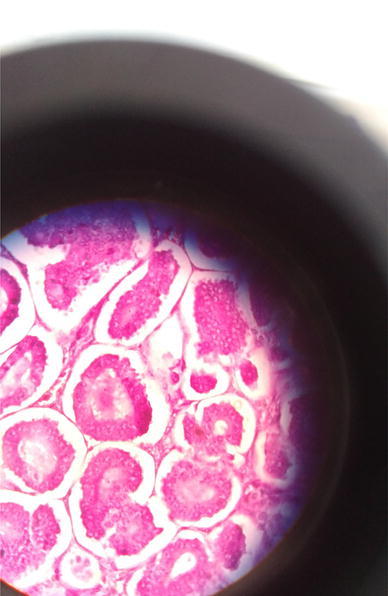

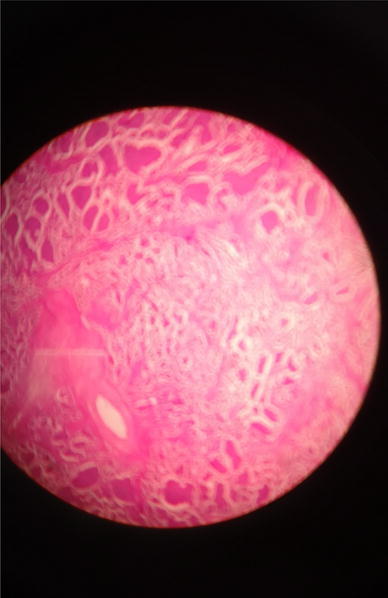

Histopathological examination revealed round to oval cells in clusters, groups, nests and tubular arrangements. The cells showed eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and round nuclei with coarse chromatin, small nucleoli and occasional mitotic figures, suggesting insular ovarian carcinoid (Figs. 4, 5 and 6).

Fig. 4.

Histopathology of ovarian tumor shows round to oval cells in clusters, groups, nests and tubular arrangements. The cells showed eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and round nuclei with coarse chromatin, small nucleoli and occasional mitotic figures

Fig. 5.

Histopathology of ovarian tumor shows round to oval cells in clusters, groups, nests and tubular arrangements. The cells showed eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and round nuclei with coarse chromatin, small nucleoli and occasional mitotic figures

Fig. 6.

Histopathology of ovarian tumor shows round to oval cells in clusters, groups, nests and tubular arrangements

The patient was screened for any possible secondary deposits but was negative.

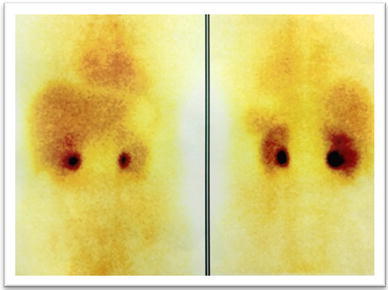

Finally, the patient was sent for a whole-body Tc-99m-HYNIC-TOC scintigraphy for neuroendocrine tumors. The 2- and 4-h images showed no evidence of any secondary deposit from the neuroendocrine tumor (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

HYNIC-TOC scan without any concentration of tracer elsewhere

The patient was symptomatically better since the surgery. Her cardiorespiratory symptoms were well controlled with oral diuretics. The patient was discharged in stable condition after explaining that she might require tricuspid valve replacement in the near future.

Discussion

Theodor Langhans first described the histology of a carcinoid tumor in 1867. Otto Lubarsch first reported two patients with ileal carcinoid tumors discovered at autopsy, in 1888 [5].

The majority of carcinoids are found within the gastrointestinal tract (55%) and bronchopulmonary region (30%). Small intestine is the most common site of carcinoids (45%), followed by the rectum (20%), appendix (17%), colon (11%) and stomach (7%) [5].

Carcinoid tumors are very uncommon and an ovarian carcinoid more so. We are presenting a case of elderly postmenopausal woman with features suggestive of carcinoid syndrome with isolated tricuspid valve involvement. The carcinoid tumor was located in the left ovary.

There have been a number of published case reports of ovarian carcinoids though rare in postmenopausal women [6, 7]. In most of those cases, radical surgery for the removal of the carcinoid tumor was the therapy of choice along with somatostatin analogs. Individuals with severe and debilitating involvement of the tricuspid valve may require valve surgery [8, 9]. Our patient responded dramatically to surgical removal of the tumor. The patient also showed no residual tumor activity on the subsequent radionuclide scan. Recurrence after early and adequate resection is rare [10]. When it is unilateral carcinoid in ovary, it is usually primary. Metastatic carcinoids in ovaries are usually bilateral [11].

Conclusion

Ovarian carcinoid with carcinoid syndrome causing severe tricuspid valve disease represents a very rare diagnosis, which should be considered in case of an elderly female patient with isolated right-sided valve disease comprising carcinoid syndrome with the negative localization of tumor in gastrointestinal tract or lungs. So patients presenting with systemic symptoms and ovarian mass need endocrine and cardiac evaluation for the early detection of carcinoid tumor and should undergo early surgery.

Professor Jayanta Chakraborty (MD.FICP.FRCP.)

is presently Professor and Director, Department of Endocrinology, Vivekananda Institute of Medical Sciences, and Endocrinologist, Woodlands Multispeciality Hospital, Kolkata. He has plenty of publications and presentations in national and international forums. He is in the editorial board and reviewer of national and international journals.

Conflict of interest

Authors have nothing to disclose and no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures followed were in accordance to ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with Helsinki declaration of 1975 and revised in 2008.

Research Involving Human Participants and Laboratory Animals

The present article is a case presentation, and it does not involve research with human or animal participation.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been taken from the patient.

Footnotes

Prof. Jayanta Chakraborty. Professor and Director, Department of Endocrinology, Vivekananda Institute of Medical Sciences, Kolkata, India, and 99 Sarat Bose Road, Kolkata, 700026, India

References

- 1.Amano Y, Mandai M, Baba T, et al. Recurrence of a carcinoid tumor of the ovary 13 years after the primary surgery: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;65:1241–1244. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ha J, Tan WA. Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors: a review. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2012;2:107. doi: 10.4172/2161-069X.1000107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siordia JA, Subramanian S. Heart carcinoid disease with patent foramen ovale treated by mini sternotomy. J Cardiothorac Med. 2017;5(3):195–197. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansencal N, Touhami I, Mitry E, et al. Patent foramen ovale in carcinoid heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142(2):e29–e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinchot SN, Holen K, Sippel RS, et al. Carcinoid tumours. Oncologist. 2008;12:1255–1269. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metwally IH, Elalfy AF, Awny S, et al. Primary ovarian carcinoid: a report of two cases and a decade registry. J Egypt Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;28:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappa I, Peros G, Lappas C, et al. Management of ovarian carcinoid syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115:205–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buda A, Giuliani D, Montano N, et al. Primary insular carcinoid of the ovary with carcinoid heart disease: unfavourable outcome of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:59–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damen N. Ovarian carcinoid presenting with right heart failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;28:pii:bcr2014204518. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaur J, Goel B, Sehgal A, Jaswal V. Primary ovarian carcinoid: a case report. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4(5):1546–1548. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20150742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genç M, Karaarslan S, Genç B, et al. A pure ovarian insular carcinoid tumor: a case report. Am J Cancer Case Rep. 2014;2:13–17. [Google Scholar]