Abstract

Introduction

Sirenomelia, also known as mermaid syndrome, is a very rare fatal congenital abnormality in which the legs are fused together, giving them the appearance of a mermaid’s tail. It is commonly associated with abnormal kidney development, genital and rectal abnormalities. Only a handful of cases have been reported in other parts of the world and is very rare in India too. This case was diagnosed postnatal in a tertiary hospital in Nagpur city of central India.

Case Presentation

A preterm male baby of weight 1.1 kg was delivered by lower-segment caesarean section to a primigravida of age 26 years. Baby presented with fusion of the entire lower limbs, imperforate anus, indiscernible genital structures, single umbilical artery and a neural tube defect. He cried spontaneously with APGAR scores 5 at 0 and 8 at 5 min and expired after 4 h. His mother had a family history of diabetes in her paternal side. The post-mortem chromosomal studies depicted 47XXY, i.e., Klinefelter’s syndrome.

Conclusions

Sirenomelia is a rare occurrence and this case gives us valuable information about the clinical presentation of it at birth and subsequent post-mortem chromosomal findings could indicate a possible genetic association.

Introduction

Sirenomelia is a very rare congenital abnormality in which the legs are fused together, giving them the appearance of a mermaid’s tail. This condition is found in approximately 1 in 100,000 live births [1] and is usually fatal [2]. It is commonly associated with renal agenesis, absent or malformed external and internal genitalia, a single umbilical artery, imperforate anus, and a blind ending large intestine [3]. Other abnormalities reported in association include double inferior vena cava [4] and angiomatous lumbosacral myelocystocele [5].

More than half the cases of sirenomelia result in stillbirth and those born alive usually die within a day or two of birth because of complications associated with abnormal kidney and bladder development and function. Only a handful of patients with sirenomelia have been reported to have survived beyond the neonatal period [6–8]. This case in a tertiary hospital in Nagpur city of central India could give valuable insights into this rare condition [9].

Case Presentation

The mother of the baby was a 26-year-old resident of Nagpur city and was a booked ANC case with a tertiary Hospital who came for a check-up when she noticed decreased foetal movements with an amenorrhoea of 7 months. She was a primigravida and was married since 10 months. She had a family history of diabetes in her father. Her menstrual and obstetric history were normal. Her general examination and p/v examination were normal, and her per-abdominal examination indicated breech presentation.

The following investigations were done at that time:

| Haematological investigations | T3, T4 and TSH levels normal |

| Blood group—AB +ve | HbA1c: 6.1% |

| Hb %—10.2 gm% | HIV—Negative |

| Blood sugar fasting: 145 mg/dl | AuAg—Negative |

| Blood sugar post-meal: 165 mg/dl | Sickling test: Negative |

The ultra sonogram done demonstrated a single live intrauterine pregnancy of 27.4 weeks with breech < 3 weeks (Symmetrical IUGR). The liquor was greatly reduced, and a foetal spine kyphoscoliotic deformity most probably a hemivertebra was seen. Along with it, a left renal pelvic dilation of foetus was seen and bladder was not seen. The FHS was 144/min, and weight of baby was 1.030 kg. The S/D ratio in both uterine arteries showed signs of uteroplacental insufficiency.

The blood sugars were controlled by diet modification, and patient did not require any anti-hypoglycemics.

In view of Primigravida of 30 weeks with breech with severe oligohydramnios and foetal distress, the patient was taken for lower-segment caesarean section and a preterm male baby of 1.1 kg was delivered. Baby cried spontaneously with APGAR score of 5 at 0 and 8 at 5 min. There was no liquor at all. Caesarean section went uneventful. But baby was a Mermaid baby (Sirenomelia) which was not diagnosed antenatal.

The baby had a birth weight of 1.1 kg and a length of 37 cm. His head and chest circumferences were 29 and 30 cm, respectively, and upper segment to lower segment ratio was 2:1. There was fusion of the entire lower limbs from the hip to the ankle with bones present in the thighs (femur) and the legs (tibia and fibula). There was no anal opening and no discernable external genital organs (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Anterior view of patient showing the fused lower limbs (with the thigh and leg bones appearing separate), absent external genitalia and severe talipes equinovarus deformity of the feet

Fig. 2.

Posterior view of patient showing the neural tube defect and absent anal opening

There was a spinal defect at the level of L2–L3. The umbilical stump revealed only one artery and one vein. The heart sounds were normal. Baby had respiratory distress followed by apnoea. Random blood sugar was 67 mg/dl. As baby was not responding to bag and mask ventilation, baby was intubated and Ambu bag done. Prognosis was explained to the relatives and baby required shifting to NICU for further management, for which relatives refused and baby expired after 4 h.

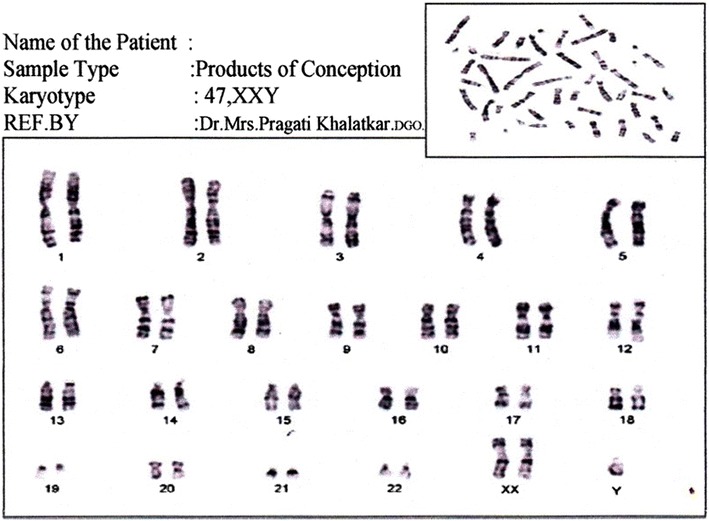

The post-mortem chromosomal studies of foetus (Fig. 3) showed a 47XXY, i.e. Klinefelter’s syndrome and the X-ray of lower limb and spines demonstrated a hemivertebra with spina bifida, fused ribs. Both lower limbs fused with normal bones and a clubfoot deformity. Parents did not give consent to clinical post-mortem for academic interests.

Fig. 3.

Postmortem Chromosomal study of foetus showing 47XXY karyotype, i.e. Klinefelter’s syndrome

Discussion

The cause of sirenomelia remains unclear; however, maternal diabetes mellitus, genetic predisposition, environmental factors and vascular steal phenomenon with the single vitelline umbilical artery diverting blood supply and nutrients from the lower body and limbs have been proposed as possible causative factors. The pattern of birth defects seen in sirenomelia is associated with abnormal umbilical cord blood vessels. Most babies with sirenomelia have only one umbilical artery and one vein, as was seen in our patient.

The spectrum of malformation of the lower limbs seen in babies with sirenomelia ranges from fusion of the legs into one lower limb with only two bones present in the entire limb (a femur and a tibia) and absence of foot structures to fusion of the skin of the lower limbs along the inner leg with fully formed and separate lower limb bones and fully formed feet which are fused at the ankles. This latter form was the case in our patient.

Confusion still exists on whether sirenomelia is a severe form of caudal regression syndrome and VACTERL (‘vertebral defects, anorectal atresia, cardiac abnormalities, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal and limb abnormalities’) association due to overlapping features. Maternal diabetes has been associated with both caudal regression syndrome and sirenomelia. The imperforate anus, a neural tube defect at the level of L2–L3, limb abnormalities and, presumably, a renal abnormality (because of the single umbilical artery) seen in our patient are all the components of VACTERL association.

The diagnosis is obvious at birth on examination of a baby, but pre-natal diagnosis can also be made as early as the first trimester by an ultrasound. In our case, the deformities were not picked up, despite 3 ultrasounds by 3 different radiologists at different centres at various stages of pregnancy. After delivery, an infantogram showed the exact bony abnormalities, while abdominal ultrasound can demonstrate abnormalities of the internal organs. The post-mortem chromosomal examination revealed a 47XXY, i.e. Klinefelter’s syndrome, and the X-ray examination was done too, showing a hemivertebra with spina bifida, fused ribs, both lower limbs fused with normal bones and a clubfoot deformity.

Conclusions

Sirenomelia is a rare occurrence and this case gives us valuable information about the clinical presentation at birth, and subsequent post-mortem chromosomal findings of 47XXY could indicate a possible genetic association.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next-of-kin for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Dr. Pragati Khalatkar

is Consultant and Director at Khalatkar Hospital for Mother and Child, Nagpur, along with Dr. Vasant Khalatker and Dr. Aishwarya Khalatkar (both are co-authors). She graduated in medicine MBBS from Barkatulla University, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, in 1993. In 1996, she joined Lata Mangeshkar hospital ICMCH and did 1 post in Medicine and 3 posts in Obs and Gynaecology. She did DGO from College of Physicians and Surgeons Mumbai and worked for 10 years in Matru Seva Sangh Mahal as Medical Officer in OBGY Dept. Her main field of interest is high-risk pregnancy. Specially worked on role of balloon tamponade in obstetric and gynaecological bleeding. She has presented papers in FIGO Sri Lanka 2014 and FIGO 2015 Vancouver along with AICOGs and many national and international conferences. Designer and Faculty for unique hands on workshop on “Pelvic Anatomy Revisited” in 2012. This workshop is highly appreciated and has been conducted at 30 national and 4 international places till now, worth mentioning are AFMC, Pune, AICC RCOG, Kolhapur, Mumbai, AICOG, Agra, Ahmedabad FIGO 2013, Sri Lanka, FIGO 2015, Vancouver, NARCHI, IMS many State conferences Abudhabi (health Ministry) and Oman.

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest in the given study.

Informed Consents

Informed consents were obtained from the patient’s family.

Research Involving Animals or Humans

The author declares that there was no involvement of any animal or human in the case presentation.

Footnotes

Dr. Pragati Khalatkar, DGO, DCH, CIMP, FICMCH, is Consultant and Director at Khalatkar Hospital for Mother and Child Nagpur; Dr. Vasant Khalatkar, MBBS, MD, FIAP, is Pediatrician and Neonatologist at Khalatkar Hospital for Mother and Child Nagpur. Dr Aishwarya Khalatkar is internee

References

- 1.Duesterhoeft SM, Ernst LM, Siebert JR, et al. Five cases of caudal regression with an aberrant abdominal umbilical artery: further support for a caudal regression-sirenomelia spectrum. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(24):3175–3184. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sriram P, Venkatesh C, Srijit R, et al. Neonatal mermaid syndrome sirenomelia. J Appl Med Sci. 2010;14(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sikandar R, Munim S. Sirenomelia, the mermaid syndrome: case report and a brief review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59(10):721–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raja V, Kannar V, Babu Rajendra Prasad CS. Sirenomelia—mermaid syndrome with oesophageal atresia: a rare case report. J Interdiscipl Histopathol. 2015;3(3):113–116. doi: 10.5455/jihp.20150711023253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dharmraj M, Gaur S. Sirenomelia: a rare case of foetal congenital anomaly. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:426. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ugwu RO, Eneh AU, Wonodi W. Sirenomelia in a Nigerian triplet: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan MJ, Todase PS. Sirenomelia, the mermaid syndrome is a rare and lethal. Sirenomelia: a case report of a rare. J Clin Neonatol. 2012;1(4):221–223. doi: 10.4103/2249-4847.106006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nosrati A, Naghshvar F, Torabizadeh Z, et al. Mermaid syndrome, Sirenomelia: a case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Rev. 2013;1(1):64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guven MA, Uzel M, Ceylaner S, et al. A prenatally diagnosed case of sirenomelia with polydactyly and vestigial tail. Genet Couns. 2008;19:419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]