Abstract

Background

This is an update of a Cochrane Review that was originally published in 2014, Issue 2. The presence of residual disease after primary debulking surgery is a highly significant prognostic factor in women with advanced ovarian cancer. In up to 60% of women, residual tumour of > 1 cm is left behind after primary debulking surgery (defined as suboptimal debulking). These women might have benefited from neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) prior to interval debulking surgery instead of primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy. It is therefore important to select accurately those women who would best be treated with primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy from those who would benefit from NACT prior to surgery.

Objectives

To determine if performing a laparoscopy, in addition to conventional diagnostic work‐up, in women suspected of advanced ovarian cancer is accurate in predicting the resectability of disease.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via Ovid, Embase via Ovid, MEDION and Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (ISI Web of Science) to July 2018. We also checked references of identified primary studies and review articles.

Selection criteria

We included studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy to determine the resectability of disease in women who are suspected of advanced ovarian cancer and planned to receive primary debulking surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of review authors independently assessed the quality of included studies using QUADAS‐2 and extracted data on study and participant characteristics, index test, target condition and reference standard. We extracted data for two‐by‐two tables and summarised these graphically. We calculated sensitivity and specificity and negative predictive values.

Main results

We included 18 studies, reporting on 14 cohorts of women (including 1563 participants), of which one was a randomised controlled trial (RCT). Laparoscopic assessment suggested that disease was suitable for optimal debulking surgery (no macroscopic residual disease or residual disease < 1 cm (negative predictive values)) in 54% to 96% of women who had macroscopic complete debulking surgery (no visible disease at end of laparotomy) and in 69% to 100% of women who had optimal debulking surgery (residual tumour < 1 cm at end of laparotomy).

Only two studies avoided partial verification bias by operating on all women independent of laparoscopic findings, and provided data to calculate sensitivity and specificity. These two studies had no false positive laparoscopies (i.e. no women had a laparoscopy indicating unresectable disease and then went on to have optimal debulking surgery (no disease > 1 cm remaining)).

Due to the large heterogeneity pooling of the data was not possible for meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Laparoscopy may be a useful tool to identify those women who have unresectable disease, as no women were inappropriately unexplored. However, some women had suboptimal primary debulking surgery, despite laparoscopy predicting optimal debulking and data are at high risk of verification bias as only two studies performed the reference standard (debulking laparotomy) in test (laparoscopy)‐positive women. Using a prediction model does not increase the sensitivity and will result in more unnecessarily explored women, due to a lower specificity.

Plain language summary

Laparoscopy in diagnosing extensiveness of ovarian cancer

Why is improving the diagnosis of extensiveness of ovarian cancer important? Ovarian cancer is a disease with a high‐mortality (death) rate. Many women (75%) are diagnosed when their disease is already at an advanced stage and 140,000 women die of this disease each year worldwide. Treatment consist of debulking surgery (removal of as much of the tumour as possible during an operation called a laparotomy ‐ normally through a long vertical cut on the abdomen) and six cycles of chemotherapy. The order in which these two treatments are given depends on the extensiveness of disease (how widespread) and on the general health of the patient. The goal of debulking surgery is to remove all visible tumour or at least to leave no residual tumour deposit bigger than 1 cm in diameter. When the diagnostic evaluation suggests that the goal of debulking surgery could not be achieved, initial treatment may be three cycles of chemotherapy to first shrink the tumour, followed by debulking surgery and then further chemotherapy to complete the course of six cycles of chemotherapy. To diagnose the extensiveness of disease by physical examination, ultrasonography, abdominal computed tomography (CT scan), and measurement of serum tumour(blood) markers are performed. An incorrect diagnosis could result in women having unsuccessful primary debulking surgery.

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this review was to investigate if laparoscopy (keyhole surgery to look inside the abdominal cavity) is accurate in predicting whether a women can be successfully operated to remove of all visible tumour or at least to leave no tumour deposits larger than 1 cm. If so, this could help to avoid operating on those women who would be better treated with chemotherapy first.

What are the main results in this review? The review included a total of 18 relevant studies, 11 of which were added for this update, and looked at 14 groups of women. In total 1563 women underwent a laparoscopy to evaluate the extensiveness of disease in the abdomen. Two studies concluded that laparoscopy was good at identifying those women in whom optimal debulking surgery was not feasible (with tumour deposits > 1 cm left after surgery) (low false positive rate for laparoscopy) and in all women the diagnosis was correct. However, even after a laparoscopy had suggested that optimal debulking surgery was feasible, some women had suboptimal primary debulking surgery where tumour deposits of > 1 cm were left). For every 100 women referred for primary debulking surgery after laparoscopy, between four and 46 will be left with visible residual tumour.

How reliable are the results of the studies in this review? A limitation of this review is that only two studies performed diagnostic laparoscopy and then went on to attempt debulking laparotomy in all women. The other studies only performed a laparotomy when laparoscopy suggested that debulking to < 1 cm tumour residue was feasible. The correct diagnosis at laparoscopy is thereby not confirmed when > 1 cm tumour residue was predicted, this is called verification bias.

Who do the results of this review apply to? Some studies used for this review also included women who underwent debulking surgery after chemotherapy or for recurrence. But mainly women were only included who were planned for primary debulking surgery. Therefore, the results presented in this review are applicable for all women who are scheduled for primary debulking surgery.

What are the implications of this review? The studies in this review suggest that laparoscopy can accurately diagnose the extensiveness of disease. When performed after standard diagnostic work‐up less women had unsuccessful debulking surgery and therefore resulting in less morbidity, Yet, there will still be women undergoing a laparotomy resulting in residual tumour of > 1 cm after surgery.

How up to date is this review? The review authors searched for and used studies published from inception of databases until July 2018.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Summary of findings table.

| To determine if adding an open laparoscopy to the diagnostic work‐up of women suspected of advanced ovarian cancer is accurate in predicting resectability of disease Population: women suspected of advanced ovarian cancer Prior testing: standard diagnostic work‐up consisting of clinical and radiological evaluation Index tests: open diagnostic laparoscopy after conventional work‐up Target condition: tumour that could not be resected at laparotomy (extensive disease) Reference standard: explorative laparotomy Studies: cohort studies, randomised controlled trial and development/validation prediction model | |||||||

| Cut off test‐positivity laparoscopy |

Sensitivity range of estimates |

Specificity range of estimates |

Prevalence of positive test result (range) |

Prevalence of negative test result (range) |

Negative Predictive Value (range) |

Number of participants |

Quality (QUADAS) |

|

Prediction of surgery result of achieving macroscopic debulking based on different criteria of unresectability or estimation 10 studies, no pooled data |

NA* | NA* | 28% (0% to 50% ) | 72% (50% to 100% ) | 54% to 96% | 1271 | High risk of bias1 Applicability concerns2 |

|

Prediction of surgery result of debulking of < 1 cm deposits based on different criteria of unresectability or estimation 9 studies, no pooled data |

0.71 to 0.95** | 1.00* | 44% (29% to 84% ) | 56% (16% to 73% ) | 69% to 100% | 1419 | High risk of bias3 Applicability concerns2 |

|

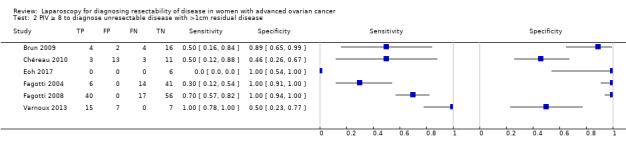

Predictive Index Value (PIV) ≥ 8 6 studies, no pooled analysis |

0.30 to 1.00 | 0.46 to 1.00 | 40% (10% to 76% ) | 60% (25% to 90% ) | 75% to 100% | 265 | High risk of bias4 Applicability concerns2 |

* No studies reported outcome of surgery of no residual macroscopic disease and performed the reference standard in all women

** Only two studies performed the reference standard in all women, sensitivity and specificity are based on these two studies 1Non of the studies performed the reference standard in test‐positive women 2 Applicability concerns based on inclusion of not only women planned for primary debulking surgery or conventional diagnostic work‐up not conclusive

3Only 2 studies performed the reference standard in test‐positive women

4 Three studies did not perform the reference standard in test‐positive women

Background

Epithelial ovarian cancer is one of the leading causes of death from gynaecological malignancies in the world (Globocan 2012). Women are commonly diagnosed with the disease at an advanced stage (Siegel 2012). This is mostly due to an early spread throughout the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity (Gallardo‐Rincón 2016). Advanced stage ovarian cancer is associated with a five‐year overall survival rate of 30% to 40% (Globocan 2012). Despite an initial response to treatment of 80%, recurrence occurs in 70% of women, and the median survival for women with advanced disease is two to four years (Munkarah 2004).

Standard treatment of women with advanced ovarian cancer is a combination of debulking surgery and chemotherapy (carboplatin with or without the addition of paclitaxel) (Makar 2016; Vergote 2013). Debulking surgery normally involves a major operation through a long mid‐line incision on the abdomen, called a laparotomy. The aim of debulking surgery is remove the womb, tubes and ovaries and all of the visible tumour deposits to leave no (macroscopic) visible tumour. If this cannot be achieved, the diameter of individual residual tumour deposits should be as small as possible, ideally < 1 cm in diameter, as survival is related to the size of the residual tumour (Bristow 2002; Du Bois 2009; Eisenkop 1998; Elattar 2011). Debulking surgery leaving the largest residual tumour deposits of > 1 cm in diameter is regarded as a suboptimal result from surgery.

An alternative strategy to primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy is treatment with chemotherapy first (called neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT)), with interval debulking surgery after three cycles of chemotherapy, followed by a further three cycles (Kehoe 2015; Vergote 2010). NACT is given in women with co‐morbidities or, if primary surgery is likely to leave large residual tumour deposits (Wright 2016). Also, if the first surgery was not a maximal attempt by an experienced gynaecological oncologist, an attempt at interval debulking surgery may improve survival. These women can be offered further surgery after three courses of chemotherapy, followed by another three courses of chemotherapy (Wright 2016). In these cases, primary debulking surgery might lead to surgical morbidity without gain of survival (Vergote 2010). Ideally, primary debulking surgery leaving residual tumour of > 1 cm should be avoided and women with disease which is not debulkable initially, should be treated with NACT (Wright 2016).

Clinical pathway

Prior test(s)

Standard work‐up consists of a physical and gynaecological examination, ultrasonography, serum cancer antigen 125 (CA‐125) sometimes in combination with human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) and computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvic area, the abdomen and the thorax. Positron emission tomography (PET) can also be performed (Hoogendam 2017). When women are thought to have operable disease after standard work‐up, primary debulking surgery is offered to those fit enough to consider major surgery.

Role of index test(s)

The ability of the standard diagnostic work‐up to predict accurately who might benefit from primary surgery is low, resulting in suboptimal debulking (> 1 cm residual tumour) in 10% to 60% of women (Gerestein 2009; Wright 2016). This suggests that current diagnostic work‐up is not sufficiently accurate and could be improved. Staging laparotomy is the most accurate way to determine if the amount of tumour in the abdomen is too extensive to achieve macroscopic debulking. Yet, a laparotomy is a very invasive intervention for diagnostic purposes.

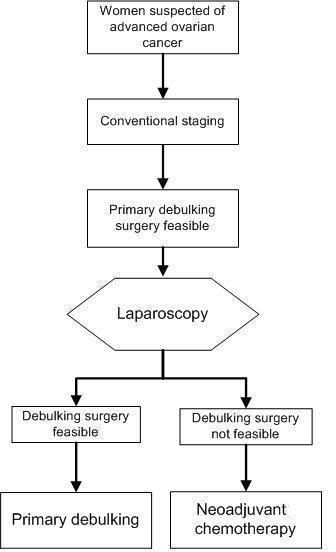

Diagnostic laparoscopy is a less invasive surgical option to determine surgical resectability. During laparoscopy a small telescope is inserted into the abdominal cavity through a small incision. The entire abdominal cavity is systematically examined; inspecting the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, pelvic peritoneum, omentum, serosa and mesentery of the large and small bowel, spleen, liver surface, paracolic gutters and diaphragm. In some institutions, a diagnostic laparoscopy is included in the standard diagnostic work‐up, and in others laparoscopy is only performed when there is doubt on the resectability of disease. This surgical diagnostic procedure, under general anaesthesia, is an additional intervention with both a risk of complications and increased costs. The overall risk of complications of a diagnostic laparoscopy is between 1% and 5% depending on the type of procedure and study population (Chi 2004). If we are able to identify, prior to surgery, those women with ovarian cancer who have metastatic disease that is likely to be too extensive to be resected at primary debulking surgery, these women could avoid primary surgery. Women who are diagnosed with too extensive disease to be removed during primary debulking surgery could be treated first with NACT (Figure 1), with a later attempt at interval debulking surgery. This strategy could improve the rate of optimal surgery, limiting unnecessary morbidity and costs.

1.

Laparoscopy is used as a triage test. If laparoscopy is positive indicating that the target condition is present (i.e. a direct debulking operation would be unsuccessful: residual cancer > 1 cm is left behind). For these women a primary debulking could be avoided and they will be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The existing pathway would be that every patient will receive an explorative laparotomy where in this flow diagram the laparoscopy is placed.

Alternative test(s)

Diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW‐MRI) is added as an extra diagnostic test to predict outcome of primary debulking surgery ( Espada 2013; Michielsen 2017).

Rationale

As standard staging tends to underestimate disease extent, potentially exposing patients to unsuccessful or more complicated surgery than expected pre‐operatively, accurate prediction of surgery result is necessary. Since the initial publication of this review new evidence has become available regarding the subject, therefore the original review was updated.

Objectives

To determine if performing a laparoscopy, in addition to conventional diagnostic work‐up, in women suspected of advanced ovarian cancer is accurate in predicting the resectability of disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies that evaluated laparoscopy as a diagnostic test to determine resectability of disease in women suspected of advanced ovarian cancer who were scheduled for primary debulking surgery after conventional staging. In these studies the extensiveness of disease diagnosed with a laparoscopy was compared with the diagnosis at laparotomy. Case‐control studies were excluded from the review because of the risk of bias in this study design. We presumed that there would be studies in which not all women had undergone reference standard (i.e. laparotomy) when the index test was positive (i.e. unsuitable for primary debulking surgery as likely to lead to suboptimal result). Therefore, we also included studies in which only the participants who had a negative result of the index test (meaning the tumour was thought to be not too extensively spread to obtain optimal debulking result) underwent the reference standard (laparotomy).

Participants

Participants included women suspected of having advanced stage ovarian cancer (FIGO stage IIB, IIC, IIIA‐C and IVA‐B), who were scheduled for primary debulking surgery, without any contraindications for laparoscopy, laparotomy, or both.

Index tests

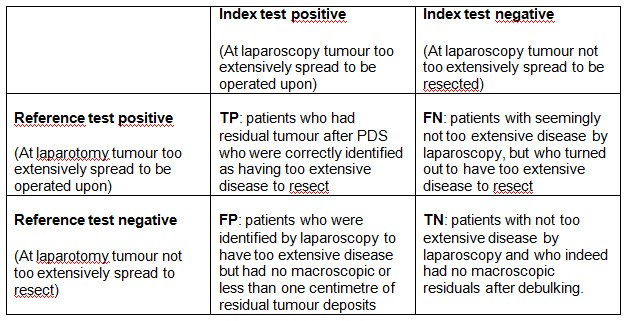

The evaluated test was an additional diagnostic laparoscopy, performed when a woman was recommended to have primary debulking surgery after standard diagnostic work‐up. Standard work‐up usually consisted of full physical and gynaecological examination, ultrasonography, serum cancer antigen 125 (CA‐125) and computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvic area, the abdomen and the thorax. A positive index test result means that the tumour was judged to be too extensively spread to be operated upon; a negative index test result means that the tumour, according to the laparoscopy, was not too extensive to be resected (Figure 2).

2.

Two by two table of index test results by reference standard outcomes. TP = True Positive, TN = True Negative, FP = False Positive, FN = False Negative

Target conditions

The target condition was deposits of ovarian cancer that could not be resected to at least < 1 cm (maximum diameter) at laparotomy and therefore making women unsuitable for primary debulking surgery. Examples of ovarian cancer deposits that cannot be resected include extensive peritoneal and mesenteric carcinomatoses (> 100 spots) or extensive metastases in the upper abdomen, such as bulky disease on the diaphragm or liver surfaces. The definition of ovarian cancer deposits that could not be resected at laparotomy was extracted from each study. Ideally, no macroscopic residual tumour is left after surgery (0 cm) to obtain the best survival, yet in the literature different cut‐off values are used for residual tumour (> 0 cm or > 1 cm), therefore we report both outcome values.

Reference standards

Laparotomy was the reference standard and allows complete exploration of the entire abdominal cavity and to locate all tumour deposits. The goal at laparotomy is to remove all macroscopic (visible) tumour, therefore representing a true impression of the resectability of ovarian cancer deposits in the abdominal cavity.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To identify eligible studies, searches were run up to 5 July 2018 in the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE via Ovid (to June week 4 2018);

Embase via Ovid (to 2018 week 27).

We also searched MEDION and Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (ISI Web of Science). The search strategies can be found in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5. No language restrictions were made.

Searching other resources

Manually searching references from articles retrieved from the computerised databases and searching relevant review articles did identify one additional reference (Chéreau 2010). This article was not found in our electronic database search.

Data collection and analysis

We followed the guidelines provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (Handbook for DTA Reviews).

Selection of studies

In pairs (MR and MB for the first version or RV and JA for the update), we independently reviewed all citations identified by the search strategies. First by title and abstract and when necessary by review of full text to determine eligibility. To be eligible, we assessed each study to determine if participants met the inclusion and exclusion criteria as described above. We included studies if sufficient information was provided to apply the selection criteria and if they included data for analysis.

Data extraction and management

We developed a data extraction form and piloted it using a subset of the articles included in the previous Cochrane review (Rutten 2014). We completed a data extraction form for all included studies. We resolved discrepancies by discussion. We retrieved the following data.

General information: title, journal, year, publication status and study design.

Sample size: number of participants meeting the criteria and total number of participants included in the analysis.

Baseline characteristics: age, FIGO stage.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The index test: technique of laparoscopy and cut‐off for test positivity.

Reference standard test: reference standard used. If not all women received a reference standard, how many and what proportion of the total did not; definition of complete, optimal and suboptimal result at laparotomy.

Whether or not the laparoscopy or laparotomy was performed by a gynaecological‐oncologist or a general gynaecologist.

Number of true positives (TP): women who had residual tumour after primary debulking surgery who were correctly identified as having too extensive disease to resect.

Number of true negatives (TN): women with not too extensive disease by laparoscopy and who had a complete (no residual tumour) or optimal (< 1 cm residual tumour) debulking result.

Number of false positives (FP): women who were identified by laparoscopy to have too extensive disease but had a complete or optimal (< 1 cm residual tumour) debulking result.

Number of false negatives (FN): women with seemingly not too extensive disease by laparoscopy, but who turned out to have too extensive disease to resect.

Number of missing, uninterpretable or doubtful results. Number of complete, optimal and suboptimal resections.

Side effects or complications due to laparoscopy.

Assessment of methodological quality

Methodological quality of the eligible studies was assessed by using QUADAS‐2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies), a tool for the assessment of quality in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy studies (Whiting 2006; Whiting 2011). The tool is based on items that cover a wide range of methodological issues in diagnostic test studies. Quadas‐2 comprises four domains: patient selection, index test, reference test and flow and timing. Each domain is assessed in terms of risk of bias and the first three domains are also assessed in terms of concerns regarding applicability. Signaling questions are included to help judge bias. The QUADAS‐2 tool is applied in four phases: summarise the review question (Appendix 6), tailor the tool and produce review‐specific guidance (Appendix 7), construct a flow diagram for the primary study, and judge bias and applicability.

We independently piloted the tool on two primary studies and no refinements were needed. After testing, the tool was used to rate all included studies. We independently (MR and MB or RV and JA) assessed the quality of the studies and any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We summarised data from each study in a two‐by‐two table of TP, FP, FN, TN, and this was used to calculate sensitivity and specificity. Studies providing insufficient data to construct two‐by‐two tables were used to present data on negative predictive values (NPV). NPV is defined as the number of women with no residual disease who were correctly defined (TN), divided by the total number of women who were thought to have no residual disease after primary debulking surgery (TN+FN) (Figure 2). We presented Individual study results graphically by plotting the estimates of sensitivity and specificity, if possible, and NPVs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All plots were done using Review Manager 5.3 and Excel. Analyses were done in Excel and SAS/STAT Software.

Investigations of heterogeneity

We expected the main sources of heterogeneity in diagnostic accuracy encountered were likely to be related to differences in the disease stage of women included in the study or to the surgeon performing the laparoscopy or laparotomy, or differences in conventional staging. However, we did not investigate sources of heterogeneity for sensitivity or specificity because only two studies reporting sufficient data to analyse sensitivity and specificity were retrieved.

We did perform investigation for heterogeneity among estimates of NPV and among estimates of test positivity. The main source of variation in NPV is expected to be the percentage of people with unresectable tumour tissue (i.e. prevalence). We used Cochran’s Q‐test and used the I2 to estimate the amount of heterogeneity (Higgins 2002) and decided not to pool data if the Cochrane’s Q‐test turned out to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). The Q‐statistic was based on the weight (1/variance) and the logit of the NPV of each study, estimated in a univariate model (only test negatives counted), because for most of these studies there were not enough data to do this in a bivariate model.

Sensitivity analyses

We expected the most important form of bias encountered would be (both partial and differential) verification bias, when a laparotomy was not performed in all women. However, we could not perform sensitivity analyses because too few studies were retrieved.

Assessment of reporting bias

Tests to detect publication bias are currently used for systematic reviews of clinical trials. However, similar tests have not been designed for reviews of diagnostic studies and in the absence of appropriate methodology, therefore we could not explore publication bias in our review.

Results

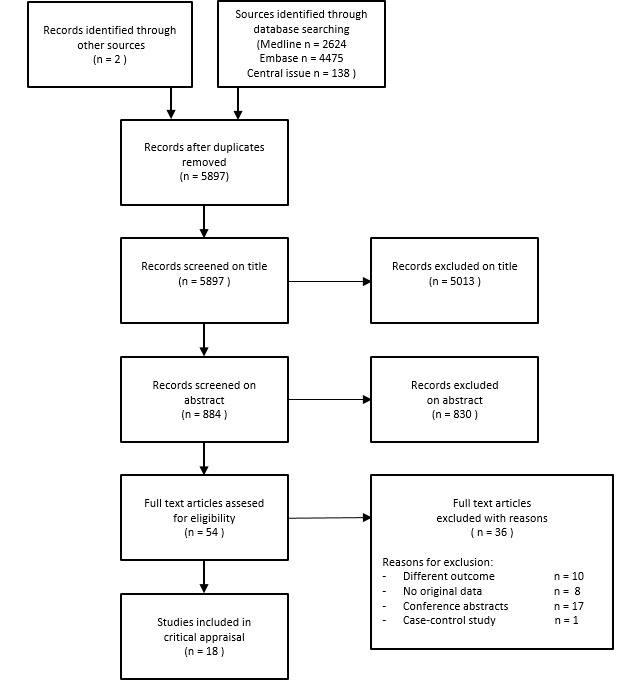

Results of the search

We identified 7237 citations from the electronic searches (138 CENTRAL, 2624 in MEDLINE and 4475 in Embase). Searching MEDION, the science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index did not lead to finding any additional citations. We checked the references of relevant reviews and primary diagnostic studies and this revealed one extra reference. After initial evaluation, we retrieved 54 full papers, 18 of which we finally considered eligible for inclusion of this review. We did not have any disagreements on studies eligible for review. A summary of the search results, including the main reason for exclusion is presented in Figure 3. Our main reasons for exclusion were if abstracts were conference abstracts and subsequently the full articles were available and included in the review or if studies did not report data about evaluation of resectability of disease (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Our search found one case‐control study which was excluded (Bresson 2016). We identified six studies reporting on two cohorts (Brun 2008; Brun 2009; Fagotti 2013; Petrillo 2015 and Vizzielli 2014; Vizzielli 2016). Details of all included studies on the design, setting, study population, target condition and reference standard of each included new study can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

3.

Study flow diagram: Results of the search for studies evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy to determine resectability of disease in women who are suspected of advanced ovarian cancer and planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional staging.

Methodological quality of included studies

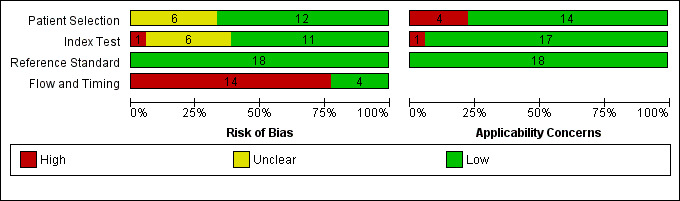

We present the results of the quality assessment using QUADAS‐2 in Figure 4 and Figure 5 for all included studies. We judged one study as low risk of bias and low concern regarding applicability in all domains (Vizzielli 2016). We judged all other studies for at least one domain to be either unclear or high risk of bias or having concerns regarding applicability. We judged two studies at high risk of bias or high concern for applicability on more than one domain (Varnoux 2013; Vergote 1998). In seven studies, the threshold for test positivity of the index test was based on a clinical estimation by the gynaecological oncologist, rather than presence of predefined criteria, therefore, we judged these studies as unclear or high in risk of bias for index test. Although in all studies the result of the reference standard (laparotomy) was interpreted with the knowledge of the result of the index test (laparoscopy), the risk of bias concerning the reference standard we still scored as low. An explorative laparotomy was performed in all index test‐negative women to judge the extensiveness of disease, furthermore all the women judged as operable underwent debulking surgery. Therefore, we can only draw a true conclusion about the resectability of the tumour deposits at the end of the surgical intervention. Because a primary debulking surgery leaving none or < 1 cm of residual tumour is associated with a better prognosis, it is likely that all women, who were thought at laparoscopy to be operable, underwent an attempt at primary debulking surgery, provided that they were still fit enough for major surgery. We judged 14 studies (Angioli 2005; Angioli 2013; Brun 2008; Brun 2009; Deffieux 2006; Dessapt 2016; Eoh 2017; Fagotti 2013; Petrillo 2015; Rosetti 2016; Rutten 2016; Varnoux 2013; Vergote 1998; Vizzielli 2014) as a high risk of bias concerning flow and timing because the laparotomy was not performed in all included women. Four studies had high concerns regarding applicability in patient selection (Chéreau 2010; Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008; Varnoux 2013). We concluded that this was because it was not possible to analyse the primary debulking results separately. The studies included not solely women before primary debulking, but also before interval debulking and surgery for recurrence. The study by Vergote 1998 had high concern applicability of the index test because there was not a clear description of test positivity or threshold used at laparoscopy.

4.

'Risk of bias' and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

5.

'Risk of bias' and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

Findings

We identified 18 studies, describing 14 cohorts of women, evaluating laparoscopy as a diagnostic test for extensiveness of disease in women with advanced ovarian cancer, of which one randomised controlled trial (RCT). Eleven articles were added in the updated version of this review. Of the articles describing similar cohorts, data of that cohort were included only once.

In the 18 studies we included there were 1563 women who were suspected to have primary advanced ovarian cancer after conventional work‐up (range 15 to 785 women) and who were evaluated by diagnostic laparoscopy for the possibility of primary debulking surgery. Of these, 1104 women actually received a primary debulking surgery after laparoscopy. In all studies, 510 women were diagnosed with unresectable disease at laparoscopy, meaning, these women were thought to have too extensive disease to achieve a residual tumour tissue < 1 cm in diameter. Four studies also included women who received laparoscopy prior to an interval debulking surgery or surgery for recurrence (range three to 73 women) (Chéreau 2010; Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008; Varnoux 2013). In these studies data on the women receiving primary debulking surgery, were not available separately.

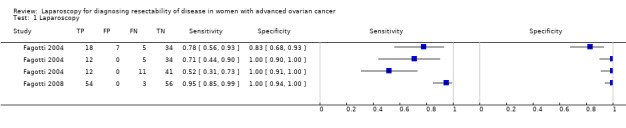

Only two studies performed a laparoscopy and laparotomy in all included women (Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008); the index‐positive women received the reference standard (laparotomy). In the other studies, these women were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT), thus leaving 444 women unverified. In the two studies where all women had the index test, all of those who were diagnosed at laparoscopy with disease that was too extensive to be resected during debulking surgery were confirmed as having unresectable disease at laparotomy (Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008). These women could have been treated with NACT as shown in Figure 1. The specificity of laparoscopy in both studies was therefore 1. Sensitivity of laparoscopy in these two studies was 0.71 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44 to 0.89) and 0.95 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.99), respectively, which means that of all women with unresectable disease at laparotomy, 71% to 95% were thought to have unresectable disease at laparoscopy. Of those thought to have resectable disease at laparoscopy, 5% to 29% of women had unresectable disease at laparotomy. Fagotti 2004 did not include all women in the analysis because in 13 women it was not possible to diagnose the extensiveness of disease at laparoscopy. The values given in the study of Fagotti 2004 were therefore based on only 80% of included women, resulting in overestimation of sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, 25% of included women in these two studies had laparoscopy before interval debulking surgery or because of recurrent disease.

In all studies, women received a laparotomy when the laparoscopy had a negative index test result (laparoscopy suggested optimal resectable disease). In total, 683 women had no macroscopic residual tumour after primary debulking surgery. However, in total 87 women had suboptimal debulking (> 1 cm residual tumour deposits) after primary debulking surgery, despite the laparoscopy indicating resectable disease. These women could have been treated with NACT initially.

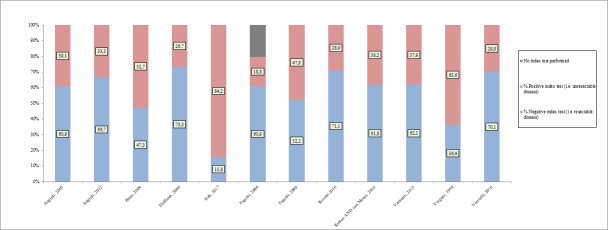

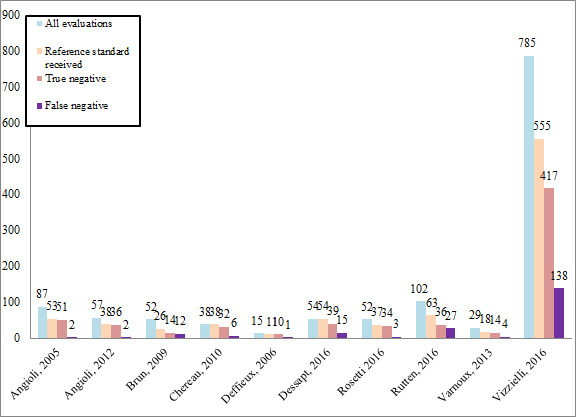

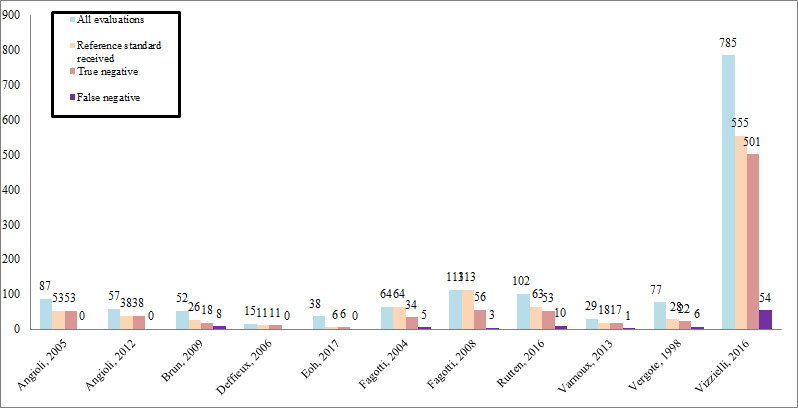

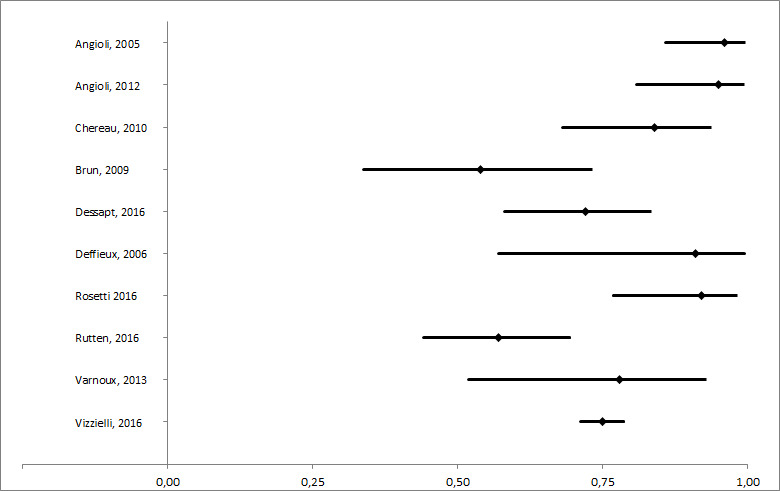

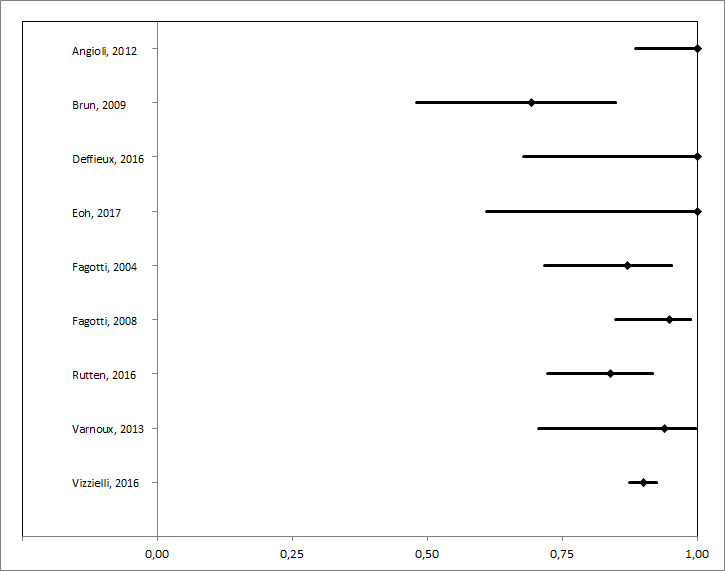

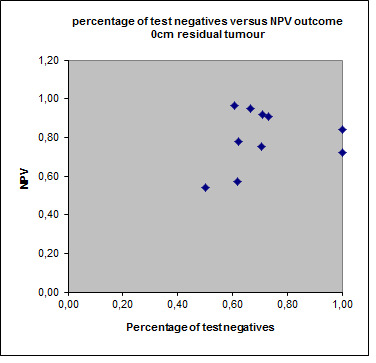

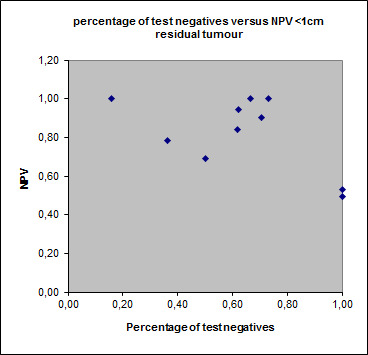

Not all studies used the same cut‐off value to express a successful debulking result. Therefore, we use two figures to show the different outcome values; any macroscopically visible disease and > 1 cm residual disease. In Figure 6 the data show the included studies with a macroscopic complete debulking result after primary debulking surgery, meaning no residual tumour tissue visible. In Figure 7, the data show included studies with an optimal debulking result, meaning residual tumour < 1 cm. Note that one study used residual tumour < 0.5 cm as the cut‐off value for optimal debulking result and was therefore not included in the figures (Vergote 1998). Negative predictive values (NPV) ranged from 54% to 96% for macroscopic complete debulking, with a median of 81 (interquartile range (IQR) 72 to 91). For optimal debulking (< 1 cm residual disease) the NPV ranged from 69% to 100%, with a median of 92 (IQR 86 to 97). Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the NPV’s of the included studies with their respective 95% CIs. In more recent studies with larger study populations, NPV result is better. For example, Vizzielli 2016 with a sample size of 555 women undergoing primary debulking surgery with a NPV of 90% for optimal debulking and a NPV of 75% for macroscopic complete debulking and Rutten 2016 describes a randomised controlled trial with a sample size of 201 and finds a NPV of 84% for optimal primary debulking and a NPV of 57% for macroscopic complete debulking. We tested for heterogeneity of all included studies with the Cochrane Q‐test, with an I2 = 56% and a P < 0.001 for the macroscopic complete debulking group and an I2 = 76% and a P < 0.001 for the optimal debulking group (< 1 cm residual disease). Based on these test results, we decided not to perform a meta‐analysis or pool the data. As expected, the studies showing a high percentage of test‐negative results of the laparoscopy had a higher NPV (Figure 10 and Figure 11). The percentage of test‐positives (those women who were thought to have too extensive disease to have optimal primary debulking surgery at laparoscopy and started with NACT) ranged between 16% and 73% and test‐negatives ranged between 27% to 84% per study (Figure 12).

6.

Absolute numbers of all women receiving laparoscopy before PDS included in analysis, women who received the reference standard, and the false negative and true negative test results for a macroscopic complete debulking surgery result (0 cm residual disease) after primary debulking surgery.

7.

Absolute numbers of all women receiving laparoscopy before PDS included in analysis, women who received the reference standard, and the false negative and true negative test results for an optimal debulking surgery result ( < 1 cm residual tumour) after primary debulking surgery.All but four studies used residual tumour tissue < 1 cm as a cut‐off definition for an optimal debulking result. Vergote 1998 used RT < 0.5 cm as a cut‐off value and was therefore not used in this figure.

8.

Negative predictive values and their 95% CI for complete debulking (RT = 0 cm) result after primary debulking surgery for each study.

9.

Negative predictive values and their 95% CI for optimal debulking (RT < 1 cm) result after primary debulking surgery for each study.

10.

Percentage of test negative results and NPV of each included study, outcome macroscopic complete (0 cm residual tumour).

11.

Percentage of test negative results and NPV of each included study, outcome < 1cm residual tumour.

12.

Percentage of women per study with a negative and positive index test result. The percentage of positive index test results varied between 27% and 84%. Only Fagotti 2004 and Fagotti 2008 validated these results. Both studies found no false positives. In the study of Fagotti 2004, 13 women could not be evaluated by laparoscopy.

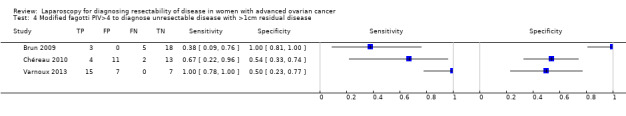

Eight studies we identified by the search, used a cut‐off value of test‐positivity derived from a prediction model using diagnostic criteria for extensiveness of disease diagnosed with a laparoscopy (Brun 2008; Chéreau 2010; Eoh 2017; Fagotti 2008; Fagotti 2013; Petrillo 2015; Vizzielli 2014; Vizzielli 2016). Fagotti 2006 developed a prediction model using a laparoscopy‐based score using the cohort of Fagotti 2004. In this prediction model, peritoneal carcinomatosis, diaphragmatic disease, mesenteric disease, omental disease, stomach infiltration, bowel infiltration and liver metastases were used as diagnostic criteria. Presence of the disease was scored with two points and the total score was used to calculate the Predictive Index Value (PIV ≥ 8). This prediction model was externally validated by Brun 2008; Chéreau 2010; Eoh 2017; Fagotti 2008; and Varnoux 2013 (see Data and analyses). Fagotti 2008 validated the PIV ≥ 8 model in a new and larger cohort; sensitivity in this study was 0.70 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.82) and specificity 1.00 (95% CI. 0.94 to 1.00). Brun 2008 also performed an external validation of the prediction model and found a sensitivity of 0.46 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.63) and a specificity of 0.89 (9% CI 0.65 to 0.99). Results from the study of Brun 2008 could lead to an over‐ or underestimation since only 26 of 55 women received a laparotomy verifying the diagnosis of the laparoscopy (see Data and analyses). The other four studies used the PIV of ≥ 8 as a cut‐off test for index test positivity (Chéreau 2010; Eoh 2017; Fagotti 2008; Varnoux 2013). NPV’s of studies using PIV of ≥ 8 as a cut‐off ranged from 0.54 to 0.84 for complete debulking result (no macroscopic residual tumour) and 0.69 to 1.00 for an optimal debulking result (residual tumour < 1 cm). Compared to studies not using PIV of ≥ 8 as a cut‐off, NPV’s ranged higher, from 0.57 to 0.96 and from 0.79 to 1.00 for complete (no macroscopic residual tumour) and optimal (residual tumour < 1 cm) debulking result, respectively. Brun 2008 modified PIV ≥ 8 model and created a modified score: PIV ≥ 4 model. Validation of the modified score was described by Chéreau 2010 and Varnoux 2013. NPV's ranged from 0.78 to 1.00.The additive value of the model appears limited. One study evaluated the additional value of adding a laparoscopy to the diagnostic work‐up compared to using only standard clinical or radiological work‐up resulting in more women considered to have resectable disease, but who were found not to be operable at laparotomy than when only using clinical or /radiological evaluation (NPV 89% versus 87%) (Fagotti 2004).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review describes the added value of laparoscopy in diagnosing resectability of disease of women with ovarian cancer before primary debulking surgery. Laparoscopy can aid in the prediction of primary debulking surgery with > 1 cm tumour residue. As studies by Vergote 2010 and Kehoe 2015 did not show that treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) gave a worse prognosis, false positive prediction with laparoscopy will not influence prognosis. Therefore, we are more interested in false negative prognosis as this will result in an unsuccessful and unnecessary debulking surgery.

We found 18 studies on 14 patient‐cohorts describing the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy following standard diagnostic work‐up planned for primary debulking surgery in women with advanced ovarian cancer, of which one was a randomised controlled trial.

In the included studies, between 16% and 73% of the women were considered to have too extensive disease to have a successful primary debulking surgery (i.e. index test positives). The remaining 27% to 84% of women were considered suitable for primary debulking surgery (i.e. index test negative) with expectation of achieving no macroscopic disease or optimal (< 1 cm residual disease) debulking result. At laparotomy, between 0% and 31% of women had > 1 cm residual tissue after primary debulking, suggesting that they could have been spared a laparotomy. The number of false positive laparoscopies; women who received NACT as primary treatment, but who would have undergone primary debulking surgery with < 1 cm residual tumour is unknown for most of the studies. Yet, because survival is not inferior to treatment with NACT, we are more interested in the false negative predicted women (Vergote 2010; Kehoe 2015). These are the women for whom laparoscopy could prevent unnecessary surgery and who might benefit from NACT initially, but had suboptimal primary debulking surgery.

Only two studies (Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008) avoided partial verification bias by performing a laparotomy in all of the included women. In these studies, no false positives were discovered at laparotomy, i.e. no women who could have had optimal debulking were thought to have suboptimally resectable disease at laparoscopy. With a sensitivity of 0.71 and 0.95 within these studies it is a promising test. However, these two studies were conducted in a heterogeneous population, including women receiving primary debulking surgery as well as interval debulking surgery. We were not able to analyse the results for the primary debulking surgery women separately. Furthermore, Fagotti 2004 did not include all women in their analysis, since in 13 cases the extensiveness of disease could not be evaluated at laparoscopy due to the presence of multiple and tenacious adherence hindering access to the abdominal and pelvic cavity. The values given in the study of Fagotti 2004 were therefore based on only 80% of included cases, resulting in overestimation of sensitivity and specificity. If these 13 women were added to the index test‐positive group, sensitivity and specificity would be 0.78 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.93) and 0.83 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.93), respectively, resulting in more women not undergoing surgery who could have had optimal primary debulking surgery. When added to the group expected by laparoscopic assessment to have no macroscopic residual disease after debulking surgery, sensitivity decreased to 0.52 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.73). Furthermore, 25% of included women in these two studies had laparoscopy before interval debulking surgery or because of recurrent disease (Data and analyses; Data table 1: Laparoscopy). Negative predictive values (NPV) ranged from 0.54 to 0.96 for macroscopic complete debulking, which means that of every 100 women referred for primary debulking surgery after laparoscopy, between four and 46 will be left with visible residual tumour. NPV ranged from 0.69 to 1.00 for optimal debulking, which means that of every 100 women referred for surgery after laparoscopy, between zero and 31 will be left with > 1 cm residual tumour after primary debulking surgery. These women will undergo a primary debulking surgery that was intended to be avoided. It is not possible to provide a pooled estimate of NPV, based on high heterogeneity. And only two studies provided data on sensitivity and specificity (Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008). Nevertheless, all studies report an added value of the diagnostic laparoscopy, although, importantly, this was without reporting increased risk of complications. Some prediction models were described and validated, however none of these models improved the predictive value compared to the subjective interpretation of the gynaecological oncologist performing the primary debulking surgery.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

This review is an updated systematic review on the accuracy of a diagnostic laparoscopy in the work‐up of women suspected of advanced ovarian cancer. We performed an extensive search addressing all available databases. However, we found wide heterogeneity within the reported studies, which precludes performing a meta‐analysis and correction for factors leading to bias.

Possible factors for heterogeneity were the reason for performing laparoscopy (standard versus only when in doubt after standard diagnostic work‐up), different exclusion criteria (for example American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of 3) and the different use of endpoint used after primary debulking surgery (i.e. no macroscopic, < 0.25 cm, < 0.5 cm and < 1 cm residual tumour tissue). Unfortunately, only in two studies was the reference standard performed in all women (Fagotti 2004; Fagotti 2008). Therefore, the data could not be pooled. In addition, we were not able to perform a sensitivity analysis to correct for this form of bias due to this small number of studies. Furthermore, the only two studies avoiding verification bias conducted their studies in a heterogeneous population, without presenting the results of the woman having primary debulking surgery women separately. Therefore, it is not clear if their results would have been the same in a more homogeneous population. However, all studies show the same positive effect of laparoscopy in the different populations. Finally, we judged the methodological quality with QUADAS‐2. This is the most recent available tool for assessing methodological quality of diagnostic accuracy studies. Signaling questions concerning quality of included studies were added or removed to adjust the quality tool to make it suitable for this specific review. The overview of study quality shows clearly that all of the studies suffered from some kind of bias or applicability concern (Figure 5), except for one (Vizzielli 2016).

Applicability of findings to the review question

The diagnostic performance of an laparoscopy may be of added value to the standard diagnostic work‐up. Based on the results of the studies described in this review, laparoscopy could be of benefit, and could be included as a standard procedure in clinical practice. When at laparoscopy the disease was judged too extensive, this was confirmed by laparotomy in two studies. However, when at laparoscopy the disease was judged as not too extensive for an optimal debulking result, there will be women who will have suboptimally resected disease (i.e. > 1 cm residual tumour) at primary debulking surgery. This is because not all tumour deposition can be visualised by laparoscopy as there is variability in what is considered resectable and which procedures are performed during laparotomy (Vergote 2010).

In some clinics, laparoscopy is already a standard intervention in the diagnostic process of women with advanced ovarian cancer. Women, who are diagnosed by laparoscopy with unresectable disease, will be treated with NACT. However, even though some women, who could be debulked to < 1 cm residual disease might not have primary surgery if they were assessed laparoscopically, this will not influence overall survival as NACT and interval debulking surgery is not deemed inferior to primary debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy (Kehoe 2015; Vergote 2010). Yet, the results of the study by Rutten 2016 estimate a reduction in primary debulking surgery leaving > 1 cm residual tumour from 39% to 10%.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Laparoscopy may be a helpful diagnostic tool in predicting the extent of residual disease after primary debulking surgery. Two studies found that no women who were thought to have suboptimally resectable disease by laparoscopy‐achieved optimal debulking. This suggests that laparoscopy would not misdirect women from primary surgery when they might benefit. Some women undergo suboptimal primary debulking surgery after laparoscopic assessment, yet the amount of women with suboptimal primary debulking surgery decreases. Therefore, laparoscopy aids in the selection of women whom are likely to benefit from primary debulking surgery. However, due to the large heterogeneity pooling of the data was not possible and careful interpretation of the study result is essential. Based on findings at laparoscopy, women are unlikely to be directed away from primary surgery when optimal debulking is possible and suboptimal primary surgery (> 1 cm residual tumour) may be prevented for some women. Use of a prediction model does not increase the sensitivity and will result in more women with suboptimal primary debulking surgery. Based on this review, laparoscopy adds to the accuracy of clinical and radiological diagnostic work‐up alone.

Implications for research.

Future research should focus on selection criteria used at laparoscopy and careful selection of women who might benefit of an extra intervention. Some women are clearly fit for optimal primary debulking and others are clearly unfit; these women could be spared the invasive laparoscopy and medical costs could be reduced. However, the group of women for whom it is uncertain if primary debulking surgery is a good option should receive a laparoscopy. Selection criteria for these women should be developed and selection criteria on which to decide debulking surgery will be unsuccessful should be universal and investigated in a prospective trial.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 October 2018 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New studies included that strengthen the previously reported conclusions. |

| 4 October 2018 | New search has been performed | Full update of the review. We updated the background with recent literature. We added 11 new studies to the results. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Jo Morrison for clinical expertise, Gail Quinn and Clare Jess for editorial assistance and Jo Platt from the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group for her help in the search for trials for inclusion in this review. We would also like to thank the Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy editorial team for their expertise.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancer Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Ovarian Neoplasms/ 2 Fallopian Tube Neoplasms/ 3 ((ovar* or fallopian tube*) adj5 (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or adenocarcinoma* or carcino* or cystadenocarcinoma* or choriocarcinoma* or malignan* or neoplas* or metasta* or mass or masses)).tw,ot. 4 (thecoma* or luteoma*).tw,ot. 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6 exp Laparoscopy/ 7 laparoscop*.tw,ot. 8 celioscop*.tw,ot. 9 peritoneoscop*.tw,ot. 10 abdominoscop*.tw,ot. 11 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 12 5 and 11 13 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 14 12 not 13

key:

tw,ot. = textword, original title

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1 exp ovary tumor/ 2 uterine tube tumor/ 3 ((ovar* or fallopian tube*) adj5 (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or adenocarcinoma* or carcino* or cystadenocarcinoma* or malignan* or neoplas* or metasta* or mass or masses)).tw,ot. 4 (thecoma* or luteoma*).tw,ot. 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6 exp laparoscopy/ 7 laparoscop*.tw,ot. 8 celioscop*.tw,ot. 9 peritoneoscop*.tw,ot. 10 abdominoscop*.tw,ot. 11 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 12 5 and 11 13 (exp Animal/ or Nonhuman/ or exp Animal Experiment/) not Human/ 14 12 not 13

key: tw,ot = textword, original title

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Ovarian Neoplasms explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Fallopian Tube Neoplasms, this term only #3 ((ovar* or fallopian tube*) near/5 (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or adenocarcinoma* or carcino* or cystadenocarcinoma* or malignan* or neoplas* or metasta* or mass or masses)) #4 thecoma* or luteoma* #5 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4) #6 MeSH descriptor Laparoscopy explode all trees #7 laparoscop* #8 celioscop* #9 peritoneoscop* #10 abdominoscop* #11 (#6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10) #12 (#5 AND #11)

Appendix 4. MEDION (http://www.mediondatabase.nl/)

ICPC code for female genital system ‐ "X"

Appendix 5. Science Citation Index

All citations found though the searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL were checked in Science Citation Index for articles which cited these articles.

Appendix 6. Quadas review question and inclusion criteria

| Category | Review Question | Inclusion Criteria |

| Women | Women with advanced stage ovarian cancer who are thought to have resectable disease after conventional diagnostic work‐up |

Women suspected of advanced stage ovarian cancer |

| Index test |

Additional open laparoscopy | Diagnostic laparoscopy |

| Target Condition |

Non‐resectable disease | Non‐resectable disease for which a definition is given |

| Reference standard |

Laparotomy | Laparotomy |

| Outcome |

NA | Sufficient data to construct a 2 x 2 table |

| Study Design | NA | Diagnostic cohort study |

Appendix 7. Quality indicator

| Risk of Bias | Applicabillity | |||

| Quality indicator | Notes | Quality indicator | Notes | |

| Domain 1 Patient Selection | Could the selection of women have introduced bias? (High/low/unclear) | Are there concerns that the included women and settings do not match the review question? (High/low/unclear) | ||

| 1. Was a consecutive or random sample of women enrolled? | “Yes” if a consecutive or random sample of women was enrolled “No” if a selected group of women was enrolled “Unclear” if there is insufficient information on enrollement | 1. Were the women diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up for advanced stage ovarian cancer? | “Yes” if women were diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up with advanced stage ovarian cancer “No” if women included in the trial are diagnosed with low‐stage disease (FIGO I or IIA) only. No high‐stage disease women in the trial “Unclear” if there is insufficient information on recruitment method, criteria for diagnosis of ovarian cancer | |

| 2. Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | “Yes” if there were no inappropriate exclusions “No” if there were inappropriate exclusions “Unclear” if there is insufficient information on exclusions | 2. Were the women planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | “Yes” if the women were planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? “No” if none of the women were planned for primary debulking surgery “Unclear” if there is insufficient information | |

| Domain 2 Index Test | Could the interpretation of the Index test have introduced bias? (High/low/unclear) | Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct or the interpretation differ from the review question? (High/low/unclear) | ||

| 1. Were the index test results interpreted without the knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | This will always be rated as yes,because the index test is performed before the reference standard | 1. Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? | “Yes” if all usual clinical data (except laparotomy results) are available when the index test is interpreted, including details of physical examination, serum tumour markers, and ultrasound and CT/MRI imaging. Also answer “yes” if one of the items is missing “No” if clinical information (as mentioned by “yes”) was not available to the gynaecologist “Unclear” if insufficient information is reported. | |

| 2.Was the threshold used prespecified? | “Yes” if a clear description of the threshold is given which was specified before start of the study “No” if no clear description is given before hand “Unclear” if there is insufficient information within the paper to determine whether or not a prespecified threshold was used | 2.Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the index test? | “Yes” if a clear description is given about when the index test is positive or negative. (e.g. what the cut‐off for too extensive abdominal disease was) “No” if there is no clear description of what is classified as too extensive disease or not “Unclear” if there is insufficient information within the paper to determine whether or not a defined threshold was used to a positive test result | |

| Domain 3 Reference Standard | Could the interpretation of the reference standard have introduced bias? (High/low/unclear) | Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the question? (High/low/unclear) | ||

| 1. Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? | “Yes” if the reference standard is laparotomy. “No” if the reference standard used is not the one defined in the protocol “Unclear” if the information is insufficient | 1.Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the reference standard? | “Yes” if a clear description is given about when the reference standard is positive or negative. (e.g. what the cut‐off at laparotomy is for too extensive abdominal disease was) “No” if there is no clear description of what is classified as too extensive disease or not “Unclear” if there is insufficient information within the paper to determine whether or not a defined threshold was used to a positive test result | |

| 2. Were the reference standard results interpreted without the knowledge of the results of the index test? | “Yes” if the report stated that the reference test is performed by individuals who did not perform the index test “No” if the reference test were done by the same person performing the index test “Unclear” if not reported. | |||

| Domain 4 Flow and Timing | Could the patient flow have introduced bias? (High/low/unclear) | |||

| 1. Is the time period between reference standard and index test short enough to be reasonably sure that the target condition did not change between the two tests? | Yes” if the time period between the index test and reference standard is not longer than 3 weeks “No” if the time period is more than 3weeks for an unacceptable high proportion of women “Unclear” if the information on the timing of tests is not provided | |||

| 2. Did all women receive the same reference standard? | “Yes” if all women underwent the reference standard (laparotomy) “No” if not all women underwent refer‐ ence standard, also those who were tested negative by index test didn't undergo reference test. “Unclear” if insufficient information is provided. | |||

| 3. Were all women included in the analysis? | “Yes” if for all women entered in the study are included in the analysis “No” if not all the women in the study are included in the analysis “Unclear” if it is not clear whether all women were accounted for | |||

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Laparoscopy | 2 | 292 |

| 2 PIV ≥ 8 to diagnose unresectable disease with >1cm residual disease | 6 | 265 |

| 4 Modified fagotti PIV>4 to diagnose unresectable disease with >1cm residual disease | 3 | 85 |

1. Test.

Laparoscopy.

2. Test.

PIV ≥ 8 to diagnose unresectable disease with >1cm residual disease.

4. Test.

Modified fagotti PIV>4 to diagnose unresectable disease with >1cm residual disease.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Angioli 2005.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Retro‐ or prospective enrolment not known. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 87 women

Mean age: 58 years (range 19 to 79)

Presentation: women with primary ovarian cancer FIGO Stage IIIC/IV, good nutrition status, WHO < 2, no contraindications for surgery, evaluation for optimal primary debulking surgery (residual tumour = 0) Diagnostics before index test: physical/gynaecological examination, ultrasonography, CA‐125, CT abdomen/pelvis, thorax X‐ray/CT Kind of surgery: PDS 53; IDS 25: No debulking surgery: 9 Setting: Department of gynaecology, University hospital Rome, Italy |

||

| Index tests | Open diagnostic laparoscopy; examination of the whole abdominal cavity, biopsies for frozen section, performed by gynaecological oncologist. If judged resectable direct debulking Cut‐off test‐positivity: prediction of complete absence of disease after debulking Complications of index test: trocar metastasis 2 cases (6% ), intraoperative complication 1 (3% ) |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: possibility of leaving no macroscopic disease at debulking surgery Criteria for target condition: extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis/involvement of bowel mesentery/bulky disease diaphragm/ multiple liver metastases/heavily bleeding tumoral tissue Reference standard: laparotomy.Test operators: gynaecological oncologist. Percentage of women reference standard performed: 61% unresectable disease at laparotomy: 2 |

||

| Flow and timing | Time between reference standard and Index test: 0 days. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Eighty‐seven women had a laparoscopy, 53 were indicated to be operable. Of these, 51 had operable disease at laparotomy and 2 not. The other 34 women were treated with NACT and 25 received an interval debulking surgery after 3 courses of chemotherapy. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients suspected of advanced ovarian cancer by conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Were patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test Diagnostic open laparoscopy | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | No | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? | No | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a "positive "result for the index test? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | No | ||

| High | |||

Angioli 2013.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Prospective study design. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 57 Diagnostics before index test: not mentioned Mean age over two groups: 58.7 (range: 41 to 78) and 59.1 (range: 32 to 80) Presentation: consecutive women affected by suspicious advanced ovarian cancer (FIGO stage III–IV) Kind of surgery: PDS 38 Setting: the Department of Gynecology of Campus Biomedico of Rome, Italy |

||

| Index tests | Diagnostic open laparoscopy. women who were judged resectable were given PDS, and those who were judged as irresectable were given NACT. Cut‐of test‐positivity: prediction of complete absence of disease after debulking surgery. Complications of index tests: were not mentioned. |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: the possibility of optimal debulking surgery. Criteria for target condition: extended visceral peritoneal metastases, large involvement of upper abdomen, extended small bowel involvement, multiple liver metastases, heavily bleeding tumour tissue. Test operators: not mentioned Percentage of women in whom reference standard is performed: 66.7% Unresectable disease at laparotomy: 94.7% . |

||

| Flow and timing | Reference standard performed after index test, time between treatment is 0 days. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Fifty‐seven laparoscopic evaluations were made; 38 women were judged resectable and received PDS, 36 women had no residual tumour tissue after surgery and 2 women had residual tumour tissue < 1 cm in diameter after surgery. 19 women were judged irresectable by S‐LSP and received NACT followed by IDS. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients suspected of advanced ovarian cancer by conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Were patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test Diagnostic open laparoscopy | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | No | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a "positive "result for the index test? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | No | ||

| High | |||

Brun 2008.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Prospective study. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 55 women Diagnostics before index test: physical/gynaecological examination, abdominal ultrasound, CA‐125, CT abdomen/pelvis, thorax X‐ray/CT, routine blood test. Mean age: 61 years; (range 21 to 88) Presentation: women suspected of ovarian cancer FIGO III‐IVwithout contraindication for surgery Kind of surgery: 26 women PDS Setting: hospital Tenon, France. | ||

| Index tests | Diagnostic laparoscopy; examination of uterus and ovaries, peritoneal surfaces, paracolic gutters, small bowel and mesentery, liver surface, omentum, diaphragm, large bowel Cut‐off test‐positivity: PIV of 8 or more Complications of index test: none reported. | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | |||

| Flow and timing | Target condition: residual disease of more than 1 cm after surgery Criteria for target condition: no extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis/ involvement of bowel mesentery/bulky disease diaphragm/unresectable upper abdomen metastases Reference standard: laparotomy. Test operators: gynaecological oncologist Percentage of women reference standard performed: 26/55 Unresectable disease at laparotomy: 8 (of 26 operated) (29 NACT). | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Retrospective external validation of the prediction model of Fagotti 2006. This was done in the same population as described in Brun 2009. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| Were the patients suspected of advanced ovarian cancer by conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Were patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test Diagnostic open laparoscopy | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a "positive "result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | No | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | No | ||

| High | |||

Brun 2009.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Retrospective study. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 55 women

Mean age: 62 years (range 21 to 88)

Presentation: women with primary ovarian cancer FIGO stage III/IV, no contraindication for surgery or malnutrition, evaluation for PDS Diagnostics before index test: physical/gynaecological examination, CA‐125, CT abdomen/pelvis, thorax X‐ray/CT, routine blood test Kind of surgery: PDS 26; IDS 26: No debulking surgery 3 Setting: Department of gynaecology, hospital Tenon, Paris, France. |

||

| Index tests | Open diagnostic laparoscopy performed by 7 surgeons, 3 gynaecological oncologists, 4 non‐gynaecological surgeons. Frozen section of tumour/metastasis. In case of operability direct debulking by laparotomy Cut‐off test‐positivity: absence of visible residual tumour was considered feasible Complications of index test: 1 trocar metastasis occurred in PDS group (2% ) |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: macroscopic residual tumour. Criteria for target condition: extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis/involvement of bowel mesentery/bulky disease diaphragm/unresectable upper abdomen metastases. Reference standard: laparotomy. Test operators: gynaecological oncologists and general gynaecologists. Percentage of women in whom reference standard performed: 47% Unresectable disease at laparotomy: 12 |

||

| Flow and timing | Time between reference standard and Index test: 0 days | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Same population as Brun 2008. Fifty‐two women had a diagnostic laparoscopy; 26 of these women were considered suitable for laparotomy. However, 8 had more than 1 cm of residual disease left after laparotomy. The other 26 women received NACT and interval debulking surgery. Debulking only when absence of visible residual tumour was considered feasible. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| Were the patients suspected of advanced ovarian cancer by conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Were patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test Diagnostic open laparoscopy | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Unclear | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a "positive "result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Unclear | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | No | ||

| High | |||

Chéreau 2010.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Retrospective study design. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 61 Diagnostics before index test: not described Mean age: 57 years Presentation: women who underwent surgery for ovarian cancer. Kind of surgery: PDS 44 women, IDS 17 women Setting: Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Tenon Hospital, Paris, France. |

||

| Index tests | Thirty‐eight women received standard laparoscopy followed by a primary debulking surgery. The findings described during laparoscopy were used to compute a Fagotti‐ and a modified‐Fagotti score. Cut‐of test‐positivity: PIV ≥ 8 Complications of index tests: not mentioned. |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: possibility of leaving no macroscopic disease at debulking surgery Criteria for target condition: not mentioned Reference standard: laparotomy Test operators: not mentioned Percentage of women in whom reference standard is performed: 100% Unresectable disease at laparotomy: 20% |

||

| Flow and timing | Reference standard performed after index test, time between treatment not mentioned. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | This study included FIGO stage I‐IV. Sub‐analysis were performed using only FIGO stage III to IV. 38 women received a laparoscopy. Thirty‐two women had no residual disease after primary debulking surgery. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients suspected of advanced ovarian cancer by conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Were patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | High | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test Diagnostic open laparoscopy | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Unclear | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a "positive "result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||