Abstract

Community Health Advocates (CHAs), known as Promotores in Spanish-speaking communities, are an important resource for the mobilization, empowerment, and the delivery of health education messages in Hispanic/Latino communities. This article focuses on understanding cultural, didactic, and logistical aspects of preparing CHAs to become competent to perform a brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in the emergency room (ER). The CHAs training emphasizes making connections with Mexican-origin young adults aged 18–30, and capitalizing on a teachable moment to effect change in alcohol consumption and negative outcomes associated with alcohol use. We outline a CHA recruitment, content/methods training, and the analysis of advantages and challenges presented by the delivery of an intervention by CHAs.

Keywords: Promotores, community health advocates, brief motivational intervention, SBIRT

At-risk and dependent drinking have been found to be highly prevalent among those seeking emergency room (ER) treatment and the majority of these patients do not seek specialized treatment for their drinking problems in the U.S. (Cherpitel & Ye, 2008). The ER visit has been thought by US and international researchers to provide a window of opportunity for changing drinking behavior (Longabaugh et al., 2001), giving rise to studies of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in this setting. While brief interventions (BI) have been effective to change drinking behavior and to minimize associated risk through resources for referrals (Ballesteros, et al., 2004; Beich, et al., 2003), studies of BI in the ER have reported mixed findings regarding efficacy (Rodríguez-Martos et al., 2003). As a result, some studies on BI in the ER are focusing on ethnicity or provider documentation of success in delivering interventions (Bernstein & Bernstein, 2008; Bernstein et al., 2009).

Community Health Advocates

Community Health Advocates (CHAs) act as outreach workers, delivering health education messages, mobilizing community members (DiClemente et al., 2002), empowering patients to become involved with the agencies’ clinical and medical staff including case managers, and improving interactions with medical staff (Ramos & Ferreira-Pinto, 2006; Ramos et al., 2006). They inform providers about the community’s health needs and provide valuable insight into the cultural relevancy of interventions (Smedley, et al, 2003). The use of CHAs has reached widespread success as a low-cost, culturally appropriate model in both community and clinical settings, and has become an integral part of health strategies of many community-based organizations (Bernstein et al 2009).

The CHAs have a long and successful history of improving healthcare among underserved populations in the Hispanic community providing a wide array of community health and social service activities based on bilingual/communication skills, bicultural and ethnic identification with the target population, and familiarity with local referral resources (Ramos et al., 2006). They have been an important link between mainstream care and more community-based healthcare practices among underserved minority populations in the Southwest United States since the 1980s (Warrick, et al., 1992), as well as among Mexican-origin individuals at the U.S.-Mexico border (Ramos, et al, 2001).

The key to the success of CHAs is their knowledge of the nuances of language and the culture among Hispanic populations (Rhodes et al., 2007), which allows them to interpret terminology, symptoms, and the patient’s worldview to providers. In this role, CHAs provide a bridge between patients and providers in finding a common understanding of the medical problem. This type of understanding can bring a more acceptable solution.

Although CHAs have been effectively used to promote behavioral change at the individual level in Hispanic community settings in the U.S. (Ramos & Ferreira-Pinto, 2006; Ramos, et al., 2006), limited data are available for the delivery of BI for drinking and related problems in a clinical setting. Moreover, there are few studies utilizing CHAs in the ER, most of which are focused on how to reduce ER visits and hospitalizations (Burns, Galbraith, Ross-Degnan, & Balaban, 2014). The adoption of SBIRT protocols, mandated by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, to require level 1 trauma centers to provide SBIRT to all patients (Committee on Trauma, 2006) provides a unique opportunity for utilizing the skills of CHAs, particularly within Mexican communities.

SBIRT studies have primarily trained practitioners (e.g. physicians, nurses) to deliver BI for substance use problems. Project ASSERT began training CHAs under a demonstration grant from the U.S. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) in 1994 at Boston City Hospital (Bernstein & Bernstein, 2009). Because this approach has proven effective, but was not tested exclusively on Hispanics/Latinos, the authors of this article partnered to implement a SBIRT with Brief Motivational Intervention with CHAs trained in working with a Latino population. The present article describes the training process of CHAs that successfully implemented a SBIRT with Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI). Described here are the instructional curricula, training methods, ongoing support and supervision, advantages and challenges in the delivery of an intervention by CHAs, lessons learned in the process of developing competencies, monitoring adherence to protocol, and evaluating outcomes associated with CHAs delivery. Detailed information on the randomized control trial, patient demographics, and specific results of the intervention can be found elsewhere (Parsa et al 2013, Cherpitel et al 2016).

Development of the Training Curricula for CHAs

The Public Health Institute subcontracted the Alliance of Border Collaboratives (ABC) to identify and recruit CHAs for the project. ABC, a nonprofit institution located in El Paso, Texas has a long history of working with CHAs in the Mexican-American community (Ramos & Ferreira-Pinto, 2002).

Formative Phase

One important consideration in providing BMI is the sensitivity this behavior change model to an individual’s cultural beliefs and values (Cherpitel, et al 2009). Studies have shown that understanding cultural differences, drinking patterns, and culturally sanctioned drinking behaviors are key elements for successful intervention strategies among ethnic minorities (Meyers, Brown, Grant, & Hasin, 2017). The development of training materials was informed by the literature on SBIRT as well as focus group data (Bernstein et al., 2007, Cherpitel et al., 2009). The Public Health Institute and Texas Tech University Health Science Center conducted the IRB review and approval.

Because a BMI had not previously been studied among Mexican-origin populations, two focus groups were conducted with individuals who met screening criteria for at-risk drinking to explore the context, motivations, and barriers to changing drinking behaviors. The focus group’s findings were useful in adapting instruments and protocols as well as developing training materials, including case studies for the initial practice sessions of the training.

The SBIRT Study

The IRB also approved the randomized controlled clinical trial of SBIRT among Mexican-origin young adults aged 18–30 admitted to an ER who screened positive for at-risk and/or dependent drinking. Following informed consent, eligible patients were assessed on the quantity and frequency of usual drinking, and alcohol-related problems at baseline, three (Parsa 2013), and 12 months post-enrollment to determine effectiveness of the intervention. Patients were randomized to receive assessment only, or assessment with intervention. Patients were given the option of being interviewed in either Spanish or English (Cherpitel, et al., 2016). Those randomized to the intervention group were introduced to a CHA who initiated the intervention. The intervention generally took place while the patient was waiting for treatment. Emergency treatment was always given priority so as not to disrupt the care of the patient. Interventions were audio taped with the patient’s consent.

Selecting CHAs

The CHAs were recruited based on their experience as advocates, bilingual/bicultural skills, ethnic identification with the target population, practical experience with Mexican-origin young adults, and potential for a strong identification with the goals of the BI project.

Eligibility criteria included that CHA’s be of Mexican origin, fluent in English and Spanish, credentialed as certified CHA’s by the State of Texas, and longtime residents of El Paso, TX. All CHAs had received training through standardized academic courses from El Paso Community College as part of their certification program; they also received on-the-job training in providing a BMI after an intensive two-day initial training program.

Training CHAs to Provide a Brief Motivational Intervention

Addressing the training needs of CHAs was a salient component of the intervention’s success. To accomplish the desired changes in how the CHAs could serve the Mexican-origin community at risk of alcohol abuse, a range of interrelated, comprehensive procedures were initiated which included: (1) establishing standards for training and standardized implementation of the SBIRT intervention; and, (2) developing capacity strategies for the CHAs related to on-the-job training and career development.

Prior to initiation of the study, CHAs were trained in BMI by research study staff from the Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health, experts in the area of the SBIRT, and in study protocols and logistics of implementing the study in the ER by the research team. The BMI was based on a brief negotiated interview (BNI) (Bernstein et al., 2007) that was adapted for the medical setting and integrated the elements of motivational interviewing and readiness to change (Mauriello, Johnson, & Prochaska, 2017). The BNI, designed to take about 15–20 minutes to complete, is essentially a conversation about behavior and choices that is patient oriented and builds self-efficacy utilizing the patient’s existing strengths and resources to facilitate positive behavior change. The BNI consists of the following elements: a) engagement in which the CHA establishes a relationship of empathy and trust through respectful and culturally competent interaction and asking the patient for permission to discuss alcohol use, b) an opportunity for the CHA to provide the patient with information about his/her drinking compared to established limits for non-hazardous drinking, and asking for patient feedback; c) use of a ‘readiness’ ruler to assess willingness to change; and d) development of a menu of options for behavior change, a cooperative activity in which the patient takes the lead and the interventionist facilitates exploration of the benefits and challenges of each strategy, ending with the patient selecting specific actions.

The training curriculum included the use of 1) a brief slide show describing evidence for the efficacy of SBIRT; 2) videos demonstrating intervention skills with simulated patients; 3) scripted scenarios for practicing skills; 4) pocket-sized plastic cards with screening guidelines, a graphic display of typical drinks and the intervention algorithm; and, 5) a website designed for independent learning (Bernstein & Bernstein, 2009). The BNI materials were adapted for use in El Paso based on information obtained from the focus groups, including two new videos developed specifically on BNI for Mexican-origin young adults.

Two days of training were provided for the CHAs, during which time they were exposed to didactic materials related to the components of intervention, and use of the Readiness to Change Ruler and the Decisional Balance Worksheet (Sobell & Sobell, 1998). Based on information from the initial assessment during recruitment into the study, patients were asked their readiness to change on a scale of 1–10 on the readiness ruler. This information was then provided to the CHAs who had been trained to use the readiness ruler to help direct their strategy for interaction with the patients.

A decisive component of the training was the opportunity to role-play common situations in the ER. Practice with simulated patients occurred, followed by a debriefing session where problems encountered were discussed. The role-play was a significant learning tool, as the practice sessions were videotaped and individually discussed with the CHAs regarding his/her experience, technique, empathy, feedback, resistance and familiarity with the process. An important component of the training was proof of competence. Videotapes were scored, using a system tested in a previous trial with multi-racial and multi-ethnic youth in a pediatric ER (Bernstein et al., 2010). The instrument measures two components: ability to complete all the elements of the protocol and ability to demonstrate basic elements of motivational interviewing: empathy, respect, shared agenda, and use of specific reflective listening skills that facilitate change talk. CHAs were required to score above 80% before being allowed to interact with ER patients.

Following the role-play with simulated patients – but still within the training program - the CHAs practiced BNI on patients in the ER. Written permission to practice and record CHA practice of interviewing skills sessions was obtained from the patients prior to the practice. Training continued until consistent above 80% competence was demonstrated. The CHAs’ ability to evaluate their own interactions with patients was an essential part of improving competencies.

On-going Support and Monitoring of the CHAs

While patients have the right to hold CHAs and their supervisors accountable, CHAs also have the right to know to whom they should turn for questions beyond their competence. While the CHAs initial training was more than adequate to gain knowledge and skills to begin the SBIRT protocol implementation, ongoing technical assistance and retraining was required throughout their involvement in the project. ABC provided the ad-hoc technical assistance with hands-on supervision via the CHA Coordinator, whose supportive role included monitoring interactions with patients on site. The CHA Coordinator was skilled in how to provide feedback and support to CHAs. Additionally, experts from Boston University had trained the CHA Coordinator on how to provide feedback on specific BMI interactions. This form of quality assurance and supervision capacity building enhanced the CHA Coordinator performance.

Boston University experts convened meetings to discuss issues in implementing the intervention. The research team provided additional feedback via review of recorded sessions to evaluate the quality of the intervention. The BI sessions were audio-taped with patient consent. Personnel at Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health reviewed the taped sessions, and scored them according to adherence protocols (Academic Emergency Medicine SBIRT Collaborative, 2005) in order to assess content and assure fidelity to the intervention. It was important for the CHAs to ascribe to the principles of fidelity to intervention protocols to avoid deviations. The review of the CHA tapes allowed the CHA Coordinator and other team members to evaluate intervention integrity and fidelity and to identify themes raised by patients, informing what was working or not within the population.

Discussion

The feasibility of SBIRT in the ER setting had initially been demonstrated through Project ASSERT, which has developed best practices in this setting (Bernstein 2007). Research on screening, brief intervention (BI), and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for substance abuse has accumulated over the past decade, and its application to various health care and nontraditional settings is gaining acceptance (Bernstein 2009). The curriculum used for training the CHAs in the present study was adapted for use among 18–30 year old Mexican-origin adults and was based on Project ASSERT. An 18-month study of BI demonstrated successful utilization of CHAs to effect positive change in drinking behaviors among a population of young adult Mexican-origin patients in the ER at the U.S.-Mexico border. At the 12-month follow-up, while improvement was found in quantity and frequency of drinking for all patients, those receiving an intervention from CHAs showed significantly greater improvement compared to those who did not receive the intervention (Cherpitel et al., 2016). This study is now part of the broader literature demonstrating significant, positive impacts of CHA-based services, and for BMI interventions in targeted populations (Cherpitel et al., 2016).

Also of interest to this study was whether interventions initiated by CHAs would result in better quality of care for patients. Patients’ personal experience with the CHAs, elicited after the intervention and at the two follow-up points, was overwhelmingly positive. They credited the CHAs with improved management of their alcohol use, identified their visit to the ER as an “eye opener” to their drinking, and welcomed the intervention received at the time of the ER visit. Patients felt empowered to make decisions about their drinking, avoiding alcohol, and risk taking behaviors associated with alcohol. During follow-up assessment telephone calls by study interviewers at 3 and 12 months, patients stated that connecting with the CHAs allowed them to open up and share personal experiences.

Study findings showed positive intervention effects and improved quality of care for patients, yet the project also faced challenges. At the onset of the study the main challenge for CHAs was gaining the respect of the professionals working in the ER. Trust was achieved through CHAs demonstrating professionalism and establishing a respectful relationship with staff and patients. While clinical staff were initially apprehensive of CHAs presence in the ER, and were unsure of their “place” within the system, continued information and inclusion of the clinical staff throughout the process helped to nurture the relationship between the CHAs and the clinical staff during the course of the study. At the conclusion of the study ER nurses were asked about their perceptions of changes brought about by the CHAs and were quite positive about these changes (Cherpitel et al., 2016). Many of the nurses acknowledged that patients seen by CHAs were more cooperative and compliant. Nurses also reported they themselves learn from CHAs intervention: they felt they became more aware of patient perceptions of the service provided during a time that is stressful for the patients; in addition, nurses utilized the CHAs’ expertise to overcome language and cultural barriers with their patients, improving the number and quality of services available to the patients (Cherpitel et al., 2016). Other clinical staff complimented the CHAs on the professionalism, knowledge, and helpfulness they demonstrated in the clinical setting.

The location of patient recruitment, assessment and intervention changed throughout the course because the busy academic ER was undergoing renovation. This necessitate both flexibility and adjustment in order to meet protocol needs and protect patient privacy. The changing ER space and routine posed many challenges to CHAs as they went about preparing to intervene with the patients. During renovations, CHAs competed for highly valued treatment spaces, and dealt with relocating patients in the middle of the intervention if the space was needed to conduct an urgent medical procedure. These difficulties were surmounted with continued on-the-job training on how to retain the integrity of the study in multiple spaces. Additionally, regular staff meetings presented the opportunity to brainstorm the best way to adapt to these changing situations.

Concerns have been raised related to integrating CHAs into the delivery of health care and allowing them to undertake the full range of roles and responsibilities of which they are capable (Balcazar et al., 2011). The emerging workforce of community health workers in the U.S. does not have a national standard for training or certification, although some states, such as Texas, have set such standards. Because of this, questions arise for employers, insurers, funders, third-party payers and consumers regarding the competence of the CHAs and the value of their services. Standardized on-the-job training, systematic technical assistance, and support can help assure the high level of competence demonstrated in this project (Escajeda 2016). The lessons learned from the use of CHA in emergency department (ED) may be relevant to research focused on other public health problems presenting in ED, such as injury prevention and violence, sexually transmitted infections or HIV, and mental health.

In light of the constraints of the ER staff and limited resources available to facilities treating ethnic minorities, CHAs are a stable core of dedicated, experienced personnel with community contacts, who, with training in a specific substance abuse intervention, can educate and motivate patients to reduce their drinking. The question of whether the benefits justify the added cost of the CHAs cannot yet be answered by available data, but is an important topic for future research on the role of CHAs in hospital-based programs.

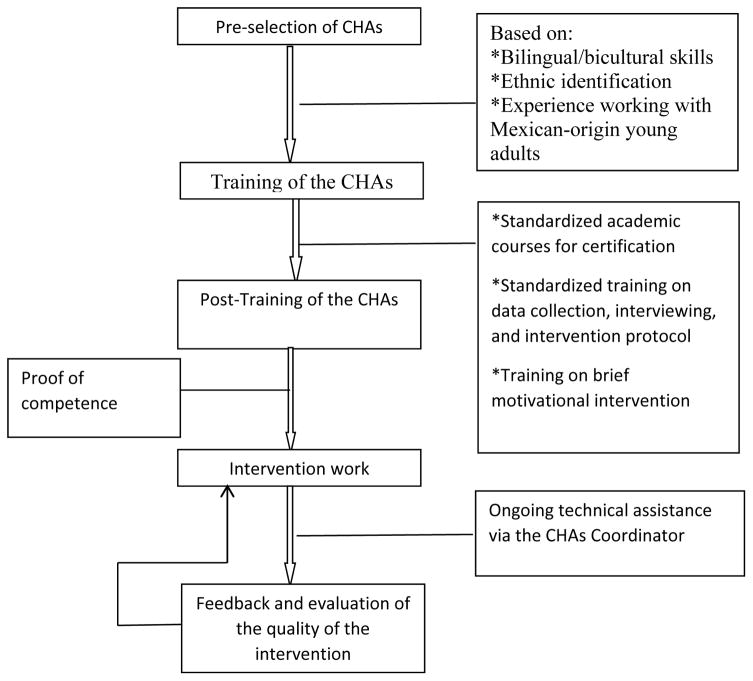

Figure 1.

Flow chart of training of the CHAs

Acknowledgments

Study supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA018119)

References

- Balcazar H, Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, Matos S, Hernandez L. Community health workers can be a public health force for change in the United States: three actions for a new paradigm. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(12):2199–2203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros J, González-Pinto A, Querejeta I, Ariño J. Brief interventions for hazardous drinkers delivered in primary care are equally effective in men and women. Addiction. 2004;99(1):103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beich A, Thorsen T, Rollnick S. Screening in brief intervention trials targeting excessive drinkers in general practice: systemic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):536–542. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Feldman J, Fernandez W, Hagan M, Mitchell P … The Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. An evidence-based alcohol Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) curriculum for Emergency Department (ED) providers improves skills and utilization. Substance Abuse: Official Publication of the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse. 2007;28(4):79–92. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Bernstein J. Effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief motivational intervention in the emergency department setting. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2008;51(6):751–754. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Bernstein JA. Evolution of an emergency department-based collaborative intervention for excessive and dependent drinking: from one institution to nationwide dissemination, 1991–2006. In: Cherpitel CJ, Borges G, Giesbrecht N, Hungerford D, Peden M, Poznyak V, Room R, Stockwell T, editors. Alcohol and Injuries. Emergency Department studies in an international perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Topp D, Shaw E, Girard C, Pressman K, Woolcock E, Bernstein J. A preliminary report of knowledge translation: lessons from taking screening and brief intervention techniques (SBI) from the research setting into regional systems of care. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(11):1225–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Edward, et al. Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(11):1174–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Judith, et al. A Brief Motivational Interview in a Pediatric Emergency Department, Plus 10-day Telephone Follow-up, Increases Attempts to Quit Drinking Among Youth and Young Adults Who Screen Positive for Problematic Drinking. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(8):890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Drug use and problem drinking associated with primary care and emergency room utilization in the U.S. general population: data from the 2005 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97(3):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in a Polish emergency room: challenges in a cultural translation of SBIRT. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2009;20(3):127–131. doi: 10.1080/10884600903047618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Woolard R, Villalobos S, Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Ramos R. Brief Intervention in the Emergency Department Among Mexican-Origin Young Adults at the US–Mexico Border: Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Using Promotores. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2016 Mar 1;51(2):154–163. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Trauma. Resources for Optimal Care of Injured Patient. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Escajeda Kameron. The Role of the Community Health Worker: An Educational Offering. College of Nursing and Health Sciences Master Project Publications; 2016. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Fedder DO, Chang RJ, Curry S, Nichols G. The effectiveness of a community health worker outreach program on healthcare utilization of west Baltimore City Medicaid patients with diabetes, with or without hypertension. Ethnicity and Disease. 2003;13(1):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, … Ries RR. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Annals of Surgery. 1999;230(4):473–480. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons MC, Tyrus NC. Systematic review of US-based randomized controlled trials using community health workers. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2007;1(4):371–381. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Ortiz M, Ferreira-Pinto JB. The evaluation of the HIV/AIDS Prevention Program conducted by community health workers. Journal of Border Health. 2001;4(2):32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006a;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age of alcohol-dependence onset: associations with severity of dependence and seeking treatment. Pediatrics. 2006b;118(3):e755–e763. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Woolard RF, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, … Gogineni A. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(6):806–816. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriello LM, Johnson SS, Prochaska JM. Meeting Patients Where They Are At: Using a Stage Approach to Facilitate Engagement. In: O’Donohue W, James L, Snipes C, editors. Practical Strategies and Tools to Promote Treatment Engagement. Springer; Cham: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Menke TJ, Giordano TP, Rabeneck L. Utilization of healthcare resources by HIV-infected white, African-American, and Hispanic men in the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95(9):853–861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers JL, Brown Q, Grant BF, Hasin D. Religiosity, race/ethnicity, and alcohol use behaviors in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2017;47(1):103–114. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa M, Liu K, Tarwater P, Cherpitel C, Woolard R, Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Ramos R, Bond J, Villalobos S, Alva I. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in an emergency department; three month outcomes of a randomized control trial among Mexican origin young adults. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2013;8(suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- Ramos RL, Ferreira-Pinto JB. A model for capacity-building in AIDS prevention programs. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(3):196–202. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.3.196.23891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos RL, Ferreira-Pinto JB. A transcultural case management model for HIV/AIDS care and prevention. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. 2006;5(2):139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos RL, Hernandez A, Ferreira-Pinto JB, Ortiz M, Somerville GG. Promovisión: designing a capacity-building program to strengthen and expand the role of promotores in HIV prevention. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(4):444–449. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MC, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in primary care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159(15):1681–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: a qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(5):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martos Dauer A, Santamariña Rubio E, Martínez Gómez X, Torralba Novella LI, Escayola Coris M, Martí Valls J, Plasència Taradach A. Identificación precoz e intervención breve en lesionades de tráfico con presencia de alcohol: primeros resultados [Early identification and brief intervention in alcohol-related traffic casualties: preliminary results] Adicciones. 2003;15(3):191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Guiding self change. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviors. 2. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Stasiak D. Culture-care theory with Mexican-Americans in an urban context. In: Leininger MM, editor. Culture Care Diversity and Universiality: A theory of nursing. New York: National League of Nursing Press; 1991. pp. 79–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrick LH, Wood AH, Meister JS, De Zapien JG. Evaluation of peer health worker prenatal outreach program for Hispanic farm worker families. Journal of Community Health. 1992;17(1):13–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01321721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DM. La promotora: linking disenfranchised residents along the border to the U.S. health care system. Health Affairs. 2001;20(3):212–218. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]