Abstract

Background: Clinical research has paid increasing attention to quality of life (QoL) in recent years, but the assessment of QoL is difficult, hampered by the subjectivity, complexity, and adherence of patients and physicians. According to previous studies, QoL in cancer patients is related to performance status (PS) and influenced by chemotherapy-related toxicity. Aidi injection, a traditional Chinese medicine injection, is used as an adjuvant drug to enhance effectiveness of chemotherapy. The study aims to investigate whether Aidi injection could improve QoL by improving PS and reducing toxicity caused by chemotherapy. Methods: A retrospective cohort study was performed at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medicine University. Data of consecutive patients diagnosed with cancers between January 2014 and June 2017 were retrieved from the electronic medical record system. After a 1:1 propensity score match, patients were then divided into 2 groups based on the therapies used, that is, Aidi injection combined with chemotherapy and chemotherapy alone, and the PS, chemotherapy-related toxicity, and combined medication information were compared. The effect of different dosages of Aidi injection on patients was further explored. Results: A total of 3200 patients were included in this study. Aidi injection combined with chemotherapy exhibited significantly benefit in PS (P < .001, odds ratio [OR] 3.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.4-4.8) compared with chemotherapy alone after adjusting for the factors that affect PS. The improvement rate of PS in the Aidi group was significantly higher than in the control group across the stratification of gender, age, tumor type, TNM stage, body mass index, nodal metastasis, prior chemotherapy, chemotherapy regimens, other Chinese tradition medicines, and chemotherapy cycle. Meanwhile, Aidi injection used synchronously with chemotherapeutic drugs could decrease the incident rate of damage to liver and kidney function, myelosuppression, and gastrointestinal reactions caused by chemotherapy. Conclusion: It was indicated that the integrative approach combining chemotherapy with Aidi injection, especially with the conventional dosage of Aidi injection, had significant benefit on QoL in cancer patients.

Keywords: Aidi injection, propensity score match, quality of life, ECOG score, performance status, chemotherapy-related toxicity

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem and has emerged as a leading cause of death globally. Although significant progress has been made in research into the cause of cancer, effective strategies to inhibit the carcinogenic process still lag behind.1 By 2020, the world population is expected to have increased to 7.5 billion; of this number, approximately 15 million new cancer cases will be diagnosed.2 After being diagnosed, chemotherapy is the most frequently used way to control disease and to extend survival.3 However, chemotherapy-induced toxicities critically cause various complications, increasing the risk of chemotherapeutic failure.4 Based on these problems, clinical workers are actively looking for complementary and alternative therapies for enhancing effectiveness and relieving symptoms of chemotherapy. In China, there has been a long history of using traditional Chinese herbal medicine (TCM) as one kind of adjuvant medicine, combined with antitumor drugs in practice for the treatment and cure of cancers.5 Undoubtedly, patients would seek these treatments when faced with cancers regardless of whether one is a supporter of TCM or not.

Aidi injection is an adjuvant TCM injection commonly used in treatment of lung cancer,6 gastric cancer,7 colorectal cancer,8 liver cancer,9 pancreatic cancer,10 malignant lymphoma,11 and esophageal cancer.12 The ingredients of Aidi injection are extracts from Renshen (Radix Ginseng), Huangqi (Astragaloside), Ciwujia (Eleutherococcus senticosus), and Banmao (Cantharidin), all of which are important Chinese herbal medicines, with ability to inhibit cancers and improve immunity.13-16 Previous studies had reported that Aidi injection has the effects of suppressing tumor metastasis, inducing apoptosis of cancer cells, and inhibiting overexpression of drug-resistant proteins induced by chemotherapy.17,18 In addition, the effects of radio-sensitization and altering the expression profiles of microRNAs may be important antitumor mechanisms of Aidi injection.19,20

In recent years, quality of life (QoL) has been recognized as a key component in clinical trial evaluations.21,22 Indeed, the vast majority of clinical trials now report QoL as either primary or secondary endpoints. Therapies that improve QoL in cancer patients are of increasing interest, especially in patients with advanced cancer in whom the scope for improving survival has proved to be limited. Because of the various restrictions in the assessment of QoL in the real-world medical environment, it is important to find surrogate endpoints of QoL as a preliminary assessment.23 Previous research had demonstrated that QoL would be affected by physical function, which is a key component of QoL and is usually assessed objectively by performance status (PS).24,25 In addition, a clinical research study had reported the QoL was related to PS and affected by chemotherapy-related toxicity, and that assessment of those indicators might lead to more effective care for patients.26

After analyzing the progress of research Aidi injection, we found that there is lack of research based on real-world data27 with a large sample size to prove the effect of Aidi injection on QoL, which might be meaningful for clinical decision making. In order to supplement the evidence-based medical evidence, a population-based retrospective cohort study was conducted to investigate whether use of Aidi injection as an adjuvant to chemotherapy might improve QoL in patients with different types of cancer. PS was used as a surrogate endpoint to assess QoL, with assessment of the effect of Aidi injection on relieving chemotherapy-related toxicity as supplementary evidence. The dosage of Aidi injection is determined according to the doctor’s advice, which is as follows: The available dosage for all patients is 20 to 100 mL per day and the conventional dosage for adults is 50 to 100 mL per day; 0.9% sodium chloride injection or 5% glucose injection are used for the dilution and it is used synchronously with chemotherapeutic drugs.

Methods

Population

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. Data of patients diagnosed with different types of cancer between January 2014 and June 2017, retrieved from the electronic medical system at the hospital, determined the sample size of this study. Each patient’s information on chemotherapy during the period of study and the data of outpatient reexamination after discharge until January 2018 was followed up. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted for the study. Inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18 years and older, (2) having complete basic information, and (3) receiving at least 1 cycle of chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria: (1) having second primary malignancy, (2) combining multiple therapies or changing chemotherapy methods, (3) missing data, and (4) using Aidi injections 3 months before enrollment or stopping use of Aidi injection during the chemotherapy period.

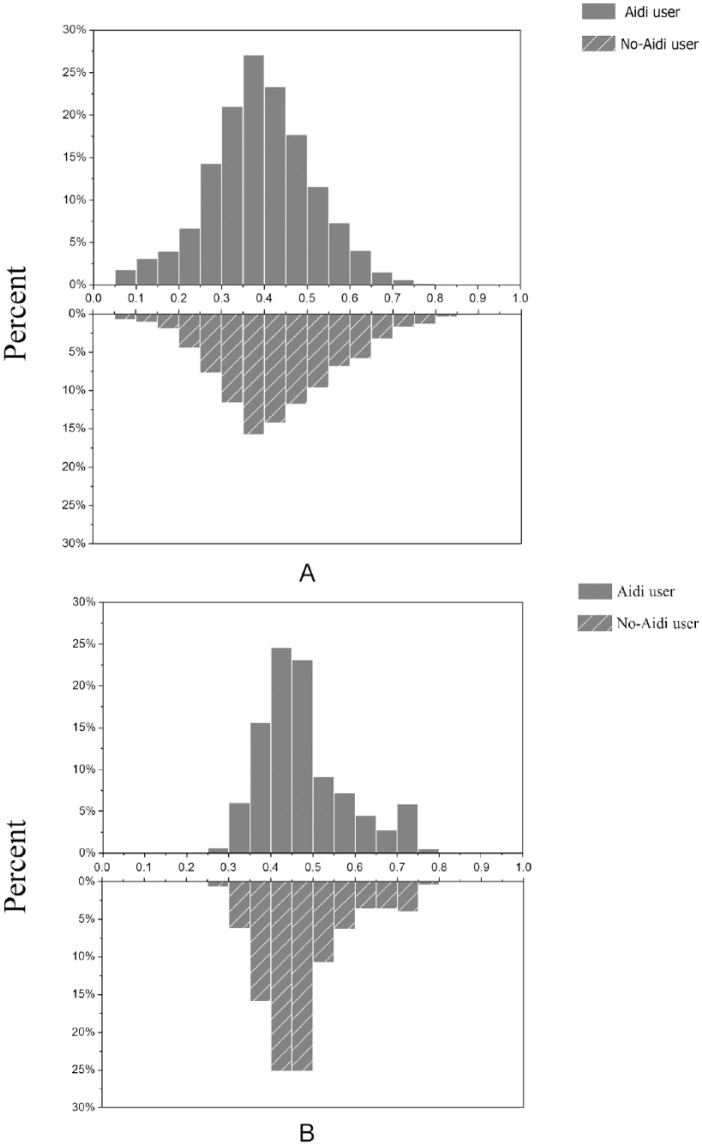

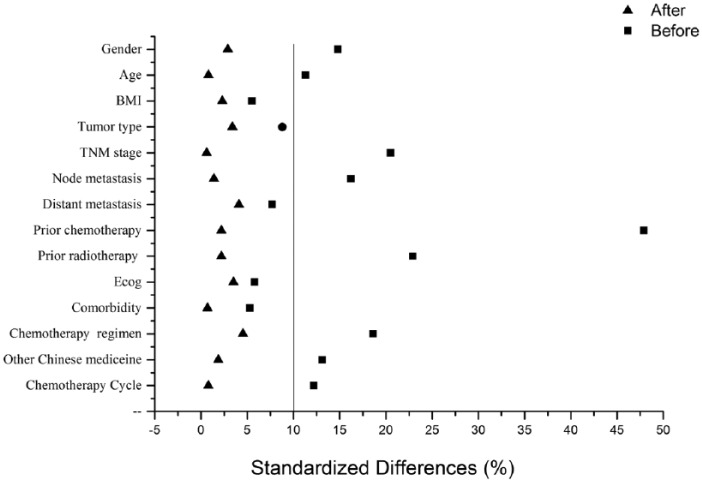

The information on covariates adjusted for confounding or used for stratification during the baseline period was collected. To control the influence of confounding factors and nonrandom assignment of patients on the results, a logistic regression model was constructed and used as the propensity score. Patients were then propensity score matched 1:1 into the Aidi group and the non-Aidi group. Covariates used for matching were as follows: gender, age, body mass index (BMI), baseline ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score, tumor type, TNM stage, node metastasis, distant metastasis, prior chemotherapy, prior radiotherapy, comorbidity, chemotherapy regimens, other TCMs, and chemotherapy cycle. The propensity score matching (PSM) algorithm used a 1:1 match with a maximum distance of 0.02. No replacement was allowed, and patients were matched only once. The distribution of propensity score was shown by a mirror histogram, and the symmetrical figure proved the match was sufficient. The balances of matched covariates were evaluated with standardized differences, and less than 10% of differences were considered matched sufficiently.

Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medicine University (PJ2017-01-08), and the need for informed consent was waived.

Chemotherapy-Related Toxicity

The indices of renal function (serum creatinine, SCr) and liver function (alanine aminotransferase, ALT and aspartate aminotransferase, AST) were assessed from routine blood analyses before chemotherapy and 1 week after chemotherapy. The cutoff values of SCr, ALT, and AST were determined according to the reference ranges of markers. Abnormal values (value >1.5 times the upper limit) before treatment were defined as hepatic insufficiency or renal insufficiency. These indexes were normal before treatment but abnormalities after treatment (value >1.5 times the upper limit) were considered as injury caused by chemotherapy. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and allergy were recorded per day according to the progress notes. Myelosuppression was assessed by the changes in counts of white blood cells (WBC), absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and platelets (PLT) before and after chemotherapy. Myelosuppression was divided into 0 to IV grades according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0 (CTCAE V4.0). WBC: 0, ⩾4.0 × 109/L, I, 3.9-3.0 × 109/L; II, 2.9-2.0 × 109/L; III, 1.9-1.0 × 109/L; IV, <1.0 × 109/L. ANC: 0, ⩾2.0 × 109/L, I, 1.9-1.5 × 109/L; II, 1.4-1.0 × 109/L; III, 0.9-0.5 × 109/L; IV, <0.5 × 109/L. PLT: 0, ⩾100 × 109/L; I, 99-75 × 109/L; II, 74-50 × 109/L; III, 49-25 × 109/L; IV, <25 × 109/L.

Performance Status

ECOG score was used to assess the PS in patients, which measures PS on a 5-point scale with 0 being “fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction” and 5 indicating that the patient is deceased. The evaluation of ECOG score in patients was performed as follows; ECOG score on day 1 of the chemotherapy cycle and at the end of chemotherapy treatment course were collected, and the changes of scores were considered as changes of PS in patients A decline in ECOG score was defined as improvement in PS. The invariable score was defined as stability and the increase in score was defined as deterioration in PS.

Combined Medication Information

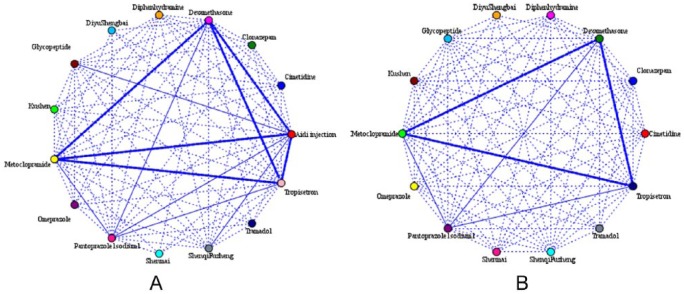

The combined medication information was analyzed according to the prescription of each patient between 2 groups. The association rule model based on the Apriori algorithm was conducted to explore the rules of combined medication. The most used 14 medicines were included in the model. The intensity of association was divided into strong (link >50%), medium (link 25%-50%), and weak (link <25%).

Statistical Analysis

The categorical variables among the Aidi group and control group were evaluated by chi-square or Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables were analyzed by t test.

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to explore the independent influence factors associated with PS. A multivariate analysis was performed with statistically significant factors from the univariate analysis (P < .05). The difference in improvement rate of PS among the patients with different characteristics in the Aidi group was also compared by logistic regression analysis.

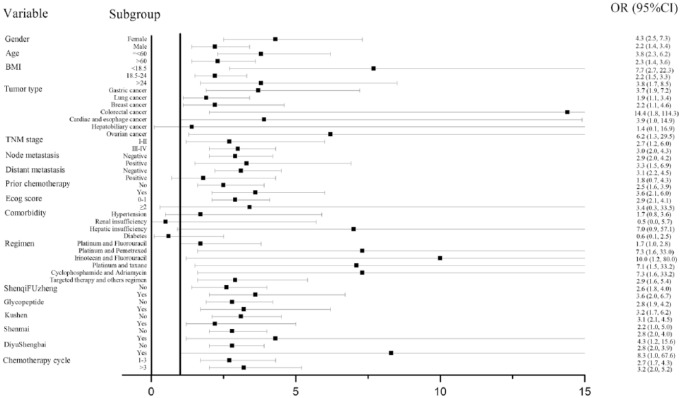

The stratified analysis of difference in improvement rate of PS between the Aidi group and the non-Aidi group was shown in the form of forest plots. When the 95% confidence interval (CI) upper and lower limits of odds ratios (ORs) were >1, that is, in the forest map, the 95% CI horizontal line did not intersect the invalid vertical line, and the horizontal line fell to the right side of the invalid line, it could be considered that the improvement rate of PS in the Aidi group is greater than that in the control group. The stratified analysis of association between the dosage of Aidi injection and QoL was shown in tabular form. Taking the non-Aidi group as the reference, the effects of different dosages of Aidi injection on PS were compared in the subgroup.

All analyses described above were performed using SPSS version 22.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 2122 Aidi injection users and 2950 non-Aidi injection users among cancer patients identified between January 2014 and June 2017 (Table 1) were enrolled in our study. A PSM was then performed and 5072 cancer patients were 1:1 matched, comprising an Aidi and non-Aidi group. A total of 3200 cancer patients were eventually included in the analysis, and the baseline characteristics after PSM are shown in Table 2. After matching, covariates were well balanced with no significant differences in demographic or tumor-related variables between the 2 groups. Propensity score with mirror histograms and standardized differences before and after matching were shown in Figures 1A-B and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Before Propensity Score Matching.

| Aidi Injection Used |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 2950) |

Yes (N = 2122) |

||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | P a |

| Gender | <.001 | ||||

| Female | 1168 | 39.6 | 995 | 46.9 | |

| Male | 1782 | 60.4 | 1127 | 53.1 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| ⩽60s | 1350 | 45.8 | 1090 | 51.4 | <.001 |

| >60 | 1600 | 54.2 | 1032 | 48.6 | |

| Mean ± SD | 59.7±10.8 | 59.2 ± 11.6 | .296 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||||

| <18.5 | 439 | 14.9 | 346 | 16.3 | .146 |

| 18.5-24 | 1962 | 66.5 | 1419 | 66.9 | |

| >24 | 549 | 18.6 | 357 | 16.8 | |

| Tumor type | <.001 | ||||

| Gastric cancer | 1482 | 50.2 | 1022 | 48.2 | |

| Lung cancer | 636 | 21.6 | 372 | 17.5 | |

| Breast cancer | 350 | 11.9 | 326 | 15.4 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 270 | 9.2 | 245 | 11.5 | |

| Cardias and esophageal cancer | 119 | 4.0 | 87 | 4.1 | |

| Hepatobiliary cancer | 34 | 1.2 | 24 | 1.1 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 59 | 2.0 | 46 | 2.2 | |

| TNM stage | .163 | ||||

| I-II | 444 | 15.1 | 350 | 16.5 | |

| III-IV | 2506 | 84.9 | 1772 | 83.5 | |

| Node metastasis | <.001 | ||||

| Negative | 1639 | 55.6 | 1325 | 62.4 | |

| Positive | 1311 | 44.4 | 797 | 37.6 | |

| Distant metastasis | <.001 | ||||

| Negative | 1771 | 60.0 | 1454 | 68.5 | |

| Positive | 1179 | 40.0 | 668 | 31.5 | |

| Prior chemotherapy | <.001 | ||||

| No | 1742 | 59.1 | 1041 | 49.1 | |

| Yes | 1208 | 40.9 | 1081 | 50.9 | |

| Prior radiotherapy | <.001 | ||||

| No | 2792 | 94.6 | 2096 | 98.8 | |

| Yes | 158 | 5.4 | 26 | 1.2 | |

| ECOG score | .038 | ||||

| 0-1 | 2822 | 95.7 | 2003 | 94.4 | |

| ⩾2 | 158 | 5.4 | 119 | 5.6 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 385 | 13.1 | 268 | 12.6 | .659 |

| Renal insufficiency | 33 | 1.1 | 66 | 3.1 | <.001 |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 495 | 16.8 | 375 | 17.7 | .406 |

| Diabetes | 136 | 4.6 | 111 | 5.2 | .311 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | <.001 | ||||

| Platinum and fluorouracil based | 1370 | 46.4 | 1006 | 47.4 | |

| Platinum and pemetrexed based | 215 | 7.3 | 166 | 7.8 | |

| Irinotecan and fluorouracil based | 266 | 9.0 | 201 | 9.5 | |

| Platinum and taxane based | 681 | 23.1 | 463 | 21.8 | |

| Cyclophosphamide and adriamycin based | 157 | 5.3 | 157 | 7.4 | |

| Targeted therapy and others regimen | 261 | 8.8 | 129 | 6.1 | |

| Other Chinese medicine | |||||

| ShenqiFuzheng injection | 827 | 28.0 | 756 | 35.6 | <.001 |

| Glycopeptide injection | 764 | 25.9 | 645 | 30.4 | <.001 |

| Kushen injection | 457 | 15.5 | 292 | 13.8 | .087 |

| Shenmai Injection | 271 | 9.2 | 168 | 7.9 | .113 |

| DiyuShengbai tablet | 161 | 5.5 | 143 | 6.7 | .058 |

| Chemotherapy cycles | <.001 | ||||

| 1-3 | 1777 | 60.2 | 1402 | 66.1 | |

| >3 | 1173 | 39.8 | 720 | 33.9 | |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Boldfaced P values are statistically significant.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients After Propensity Score Matching.

| Aidi Injection Used |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1600) |

Yes (N = 1600) |

||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | P a |

| Gender | .414 | ||||

| Female | 706 | 44.1 | 729 | 45.6 | |

| Male | 894 | 55.9 | 871 | 55.4 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| ⩽60 | 791 | 49.4 | 784 | 49.0 | .805 |

| >60 | 809 | 50.6 | 816 | 51.0 | |

| Mean ± SD | 60.7 ± 10.4 | 60.5 ± 11.1 | .8085 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||||

| <18.5 | 252 | 15.8 | 260 | 16.2 | .665 |

| 18.5-24 | 1105 | 69.1 | 1082 | 67.6 | |

| >24 | 243 | 15.2 | 258 | 16.1 | |

| Tumor type | .101 | ||||

| Gastric cancer | 798 | 49.9 | 815 | 50.9 | |

| Lung cancer | 288 | 18.0 | 294 | 18.4 | |

| Breast cancer | 212 | 13.2 | 238 | 14.9 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 154 | 9.6 | 108 | 6.8 | |

| Cardiac and esophageal cancer | 86 | 5.4 | 77 | 4.8 | |

| Hepatobiliary cancer | 20 | 1.2 | 23 | 1.4 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 42 | 2.6 | 45 | 2.8 | |

| TNM stage | .825 | ||||

| I-II | 274 | 17.1 | 278 | 17.4 | |

| III-IV | 1326 | 82.9 | 1322 | 82.6 | |

| Node metastasis | .689 | ||||

| Negative | 979 | 61.2 | 990 | 61.9 | |

| Positive | 621 | 38.8 | 610 | 38.1 | |

| Distant metastasis | .244 | ||||

| Negative | 1054 | 65.9 | 1085 | 67.8 | |

| Positive | 546 | 34.1 | 515 | 32.2 | |

| Prior chemotherapy | .524 | ||||

| No | 830 | 51.9 | 812 | 50.7 | |

| Yes | 770 | 48.1 | 788 | 49.9 | |

| Prior radiotherapy | .351 | ||||

| No | 1582 | 98.9 | 1576 | 98.5 | |

| Yes | 18 | 1.1 | 24 | 1.5 | |

| ECOG score | .317 | ||||

| 0-1 | 1504 | 94.0 | 1517 | 94.8 | |

| ⩾2 | 96 | 6.0 | 83 | 5.2 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 197 | 12.3 | 204 | 12.8 | .709 |

| Renal insufficiency | 24 | 1.5 | 24 | 1.5 | .999 |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 262 | 16.4 | 256 | 16.0 | .773 |

| Diabetes | 73 | 4.6 | 75 | 4.7 | .866 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | |||||

| Platinum and fluorouracil based | 770 | 48.2 | 773 | 48.2 | .585 |

| Platinum and pemetrexed based | 83 | 5.2 | 96 | 6.0 | |

| Irinotecan and fluorouracil based | 148 | 9.3 | 136 | 8.5 | |

| Platinum and taxane based | 392 | 24.5 | 413 | 25.8 | |

| Cyclophosphamide and adriamycin based | 110 | 6.9 | 102 | 6.4 | |

| Targeted therapy and others regimen | 96 | 6.0 | 80 | 5.0 | |

| Other Chinese medicine | |||||

| ShenqiFuzheng injection | 503 | 31.4 | 497 | 31.1 | .819 |

| Glycopeptide injection | 424 | 26.5 | 433 | 27.1 | .719 |

| Kushen injection | 255 | 15.9 | 268 | 16.8 | .534 |

| Shenmai Injection | 123 | 7.7 | 123 | 7.7 | .999 |

| DiyuShengbai tablet | 50 | 3.1 | 65 | 4.1 | .154 |

| Chemotherapy cycles | |||||

| 1-3 | 1049 | 65.6 | 1055 | 65.9 | .823 |

| >3 | 551 | 34.4 | 545 | 34.1 | |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Figure 1.

Mirror histograms (A) before propensity score matching and (B) after propensity score matching.

Figure 2.

Standardized differences.

Chemotherapy-Related Toxicity

As shown in Table 3, the incidence rate of damage to renal and liver function, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in the Aidi group was significantly lower than that in the control group both in short and long chemotherapy cycles. As shown in Table 4, the combination of Aidi injection and chemotherapy significantly decreased the incidence rate of chemotherapy-related leucopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia compared with chemotherapy alone (P < .001, P = .033, and P < .001, respectively).

Table 3.

Chemotherapy-Related Toxicity.

| Aidi injection used |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1600) |

Yes (N = 1600) |

||||

| Toxicity | n | % | n | % | P a |

| Short cycle (1-3) | 1049 | 65.6 | 1055 | 65.9 | |

| AST elevation | 114 | 10.9 | 80 | 7.6 | .009 |

| ALT elevation | 162 | 15.4 | 96 | 9.1 | <.001 |

| CR elevation | 30 | 2.9 | 16 | 1.5 | .035 |

| Nausea, vomiting | 463 | 43.9 | 367 | 34.8 | <.001 |

| Diarrhea | 93 | 8.9 | 52 | 4.9 | <.001 |

| Constipation | 69 | 6.6 | 54 | 5.1 | .154 |

| Allergy | 41 | 3.9 | 38 | 3.6 | .711 |

| Long cycle (>3) | 551 | 34.4 | 545 | 34.1 | |

| AST elevation | 99 | 17.9 | 74 | 13.6 | .046 |

| ALT elevation | 114 | 20.7 | 83 | 15.2 | .019 |

| CR elevation | 49 | 8.5 | 30 | 5.5 | .030 |

| Nausea, vomiting | 293 | 53.2 | 227 | 41.7 | <.001 |

| Diarrhea | 74 | 13.4 | 42 | 7.7 | .002 |

| Constipation | 51 | 9.2 | 39 | 7.2 | .205 |

| Allergy | 55 | 6.4 | 26 | 4.8 | .254 |

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CR creatinine.

Boldfaced P values values are statistically significant.

Table 4.

Chemotherapy-Related Hematological Toxicity.

| Grade |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Group | 0, n (%) | I, n(%) | II, n (%) | III, n (%) | IV, n (%) | P a |

| Leucopenia | <.001 | ||||||

| Aidi group | 1221 (76.3) | 166 (10.4) | 174 (10.8) | 38 (2.4) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Control group | 1110 (69.4) | 232 (14.5) | 218 (13.6) | 35 (2.2) | 5 (0.3) | ||

| Neutropenia | .033 | ||||||

| Aidi group | 1248 (78.0) | 153 (9.6) | 149 (9.3) | 47 (2.9) | 3 (0.2) | ||

| Control group | 1207 (75.4) | 183 (11.4) | 169 (10.6) | 32 (2.0) | 9 (0.6) | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | <.001 | ||||||

| Aidi group | 1448 (90.5) | 97 (6.1) | 48 (3.0) | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Control group | 1365 (85.3) | 133 (8.3) | 77 (4.8) | 17 (1.1) | 8 (0.5) | ||

Boldfaced P values are statistically significant.

Performance Status

The number of patients with decreased ECOG score (ie, improved PS) for those who underwent Aidi injection combined with chemotherapy was 137 while it was 48 for those who underwent chemotherapy alone, with a significant difference. The patients with increasing ECOG score (ie, worse PS) in the Aidi group were significantly less than those in the control group. Overall, there was a significant improvement of PS in patients in the Aidi group (Table 5).

Table 5.

Changes in Performance Status.

| Aidi Injection Used |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1600) |

Yes (N = 1600) |

||||

| Performance Status | n | % | n | % | P a |

| Deterioration | 59 | 3.7 | 6 | 0.4 | <.001 |

| Stabilization | 1493 | 93.3 | 1457 | 91.1 | <.001 |

| Improvement | 48 | 3.0 | 137 | 8.5 | <.001 |

Boldfaced P values are statistically significant.

The results of the univariate analysis are shown in Table 6. Patients with node metastasis (P < .001, OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.3-0.6), distant metastasis (P < .001, OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.2-0.4), worse baseline ECOG score (P = .045, OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.1-1.0), and hepatic insufficiency (P < .001, OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1-0.5) were significantly associated with worse PS. On the contrary, Aidi injection (P < .001, OR 2.9, 95% CI 2.1-4.1) and long chemotherapy cycles (P < .001, OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.5-2.8) were the influence factors associated with better PS. Patients with lung cancer, breast cancer, cardia and esophageal cancer, and ovarian cancer had better improvement rate of PS compared with patients with gastric cancer. According to the results of multivariate analysis, Aidi injection was a significant independent factor of improving PS after adjusting for the confounding factors (P < .001, OR 3.4, 95% CI 2.4-4.8). Other independent factors were tumor types, node metastasis, distant metastasis, baseline ECOG score, hepatic insufficiency, and chemotherapy cycle.

Table 6.

Logistic Regression Model With Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% CI of Improvement Rate of Performance Status.

| Univariable |

Multivariable |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Crude OR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | [reference] | |||||

| Male | 1.2 | 0.9-1.6 | .294 | |||

| Age, years | ||||||

| ⩽60 | [reference] | |||||

| >60 | 0.8 | 0.6-1.2 | .291 | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||||

| <18.5 | [reference] | |||||

| 18.5-24 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.2 | .264 | |||

| >24 | 1.3 | 0.8-2.1 | .303 | |||

| Tumor type | ||||||

| Gastric cancer | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Lung cancer | 3.1 | 2.1-4.6 | <.001 | 3.7 | 2.3-5.9 | <.001 |

| Breast cancer | 3.0 | 1.9-4.6 | <.001 | 3.1 | 1.9-5.1 | <.001 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.4 | 0.7-2.6 | .371 | 0.3 | 0.1-1.0 | .060 |

| Cardiac and esophageal cancer | 2.7 | 1.4-5.1 | .002 | 2.5 | 1.3-4.8 | .007 |

| Hepatobiliary cancer | 2.2 | 0.7-7.3 | .200 | 2.6 | 0.7-9.1 | .135 |

| Ovarian cancer | 5.8 | 3.1-10.9 | <.001 | 6.8 | 3.4-13.7 | <.001 |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I-II | [reference] | |||||

| III-IV | 1.0 | 0.7-1.4 | .848 | |||

| Node metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Positive | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 | <.001 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 | <.001 |

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Positive | 0.3 | 0.2-0.4 | <.001 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.4 | <.001 |

| Prior chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 0.9 | 0.7-1.3 | .683 | |||

| Prior radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 2.2 | 0.9-5.8 | .094 | |||

| ECOG score | ||||||

| 0-1 | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| ⩾2 | 0.4 | 0.1-1.0 | .045 | 0.3 | 0.1-0.9 | .024 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1.4 | 0.9-2.1 | .121 | |||

| Renal insufficiency | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1.1 | 0.3-3.5 | .918 | |||

| Hepatic insufficiency | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 0.2 | 0.1-0.5 | <.001 | 0.5 | 0.2-1.0 | .037 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 0.9 | 0.4-1.9 | .793 | |||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||

| Platinum and fluorouracil based | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Platinum and pemetrexed based | 2.3 | 1.3-4.0 | .003 | 1.2 | 0.6-2.3 | .589 |

| Irinotecan and fluorouracil based | 1.0 | 0.5-1.8 | .928 | 1.3 | 0.7-2.5 | .444 |

| Platinum and taxane based | 1.6 | 0.8-3.0 | .161 | 1.7 | 0.9-3.4 | .127 |

| Cyclophosphamide and adriamycin based | 1.9 | 1.1-3.4 | .019 | 1.1 | 0.6-2.0 | .870 |

| Targeted therapy and others regimen | 1.8 | 1.2-2.5 | .002 | 1.2 | 0.8-1.8 | .353 |

| Other Chinese medicine | ||||||

| ShenqiFuzheng injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1.1 | 0.8-1.5 | .477 | |||

| Glycopeptide injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.7-1.4 | .965 | |||

| Kushen injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.7-1.5 | .975 | |||

| Shenmai injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1,0 | 0.6-1.8 | .878 | |||

| DiyuShengbai tablet | ||||||

| No | [reference] | |||||

| Yes | 1.8 | 1.0-3.5 | .067 | |||

| Chemotherapy cycles | ||||||

| 1-3 | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| >3 | 2.1 | 1.5-2.8 | <.001 | 2.8 | 2.1-3.9 | <.001 |

| Aidi injection used | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 2.9 | 2.1-4.1 | <.001 | 3.4 | 2.4-4.8 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Boldfaced P values are statistically significant.

In a stratified analysis (Figure 3), the result indicated that Aidi injection led to a durable improvement in PS across almost all subgroups Stratified by gender, age, TNM stage, node metastasis or not, prior chemotherapy or not, baseline ECOG score, chemotherapy regimens, other Chinese medicines and different chemotherapy cycles, the Aidi group showed higher improvement rate of PS than that in the control group. In subgroups of patients with hepatobiliary cancer, distant metastasis and comorbidity (hypertension, renal insufficiency, hepatic insufficiency, and diabetes), the improvement rate of PS showed no statistical difference between the 2 groups. However, the ORs from almost all subgroups suggested that cancer patients receiving chemotherapy might benefit from Aidi injection.

Figure 3.

Stratified analysis.

The difference in improvement rate of PS among the patients with different characteristics in the Aidi group is shown in Table 7. Aidi injection was shown to be less effective in patients with advanced age (>60 years), node metastasis, distant metastasis, worse baseline ECOG score compared to patients with younger age (⩽60 years), no node metastasis, no distant metastasis and better baseline ECOG score. In addition, Aidi injection had better effects for patients with lung cancer, breast cancer, cardia and esophageal cancer and ovarian cancer compared to patients with gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, and hepatobiliary cancer. It was worth noting that Aidi injection combined with platinum and pemetrexed or taxane should be more beneficial to patients in comparison with other chemotherapy regimens. From the perspective of treatment cycles, patients with long chemotherapy cycles might have a higher improvement rate of PS.

Table 7.

Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% CI of Performance Status Benefit Associated With Aidi Injection for Patients With Different Characteristics.

| Aidi User (N = 1600) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR |

Adjusted OR |

|||||

| Variable | Crude OR | 95% CI | P a | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P a |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Male | 1.4 | 1.0-2.0 | .064 | 1.1 | 0.7-1.7 | .798 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| ⩽60 | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| >60 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.1 | .121 | 0.5 | 0.4-0.8 | .004 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||||

| <18.5 | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| 18.5-24 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.2 | .264 | 1.0 | 0.6-1.7 | .932 |

| >24 | 1.3 | 0.8-2.1 | .303 | 1.5 | 0.8-2.9 | .242 |

| Tumor type | ||||||

| Gastric cancer | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Lung cancer | 2.6 | 1.6-4.2 | <.001 | 2.4 | 1.3-4.4 | .004 |

| Breast cancer | 2.6 | 1.5-4.2 | <.001 | 2.1 | 1.0-4.2 | .041 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.9 | 0.9-3.9 | .080 | 1.5 | 0.7-3.4 | .290 |

| Cardiac and esophageal cancer | 2.9 | 1.4-6.0 | .005 | 3.3 | 1.4-7.3 | .004 |

| Hepatobiliary cancer | 1.6 | 0.4-7.0 | .537 | 2.1 | 0.4-9.8 | .367 |

| Ovarian cancer | 6.4 | 3.1-13.2 | <.001 | 6.9 | 2.8-17.2 | <.001 |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I-II | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| III-IV | 1.0 | 0.6-1.6 | .948 | 1.5 | 0.8-2.6 | .188 |

| Node metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Positive | 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 | <.001 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.7 | <.001 |

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Positive | 0.2 | 0.1-0.4 | <.001 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.3 | <.001 |

| Prior chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.7-1.4 | .924 | 0.9 | 0.6-1.3 | .583 |

| Prior radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 2.9 | 1.1-7.8 | .039 | 1.0 | 0.7-1.6 | .874 |

| ECOG score | ||||||

| 0-1 | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| ⩾2 | 0.4 | 0.1-1.2 | .109 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.8 | .024 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 0.7 | 0.4-1.3 | .235 | 1.1 | 0.6-2.3 | .687 |

| Renal insufficiency | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 0.5 | 0.1-3.4 | .447 | 0.5 | 0.1-4.3 | .499 |

| Hepatic insufficiency | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 0.3 | 0.1-0.6 | <.001 | 0.5 | 0.2-0.8 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 0.4 | 0.1-1.4 | .158 | 0.5 | 0.1-1.9 | .336 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||

| Platinum and fluorouracil based | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Platinum and pemetrexed based | 3.0 | 1.6-5.6 | <.001 | 2.4 | 1.1-5.4 | .037 |

| Irinotecan and fluorouracil based | 1.1 | 0.5-2.4 | .731 | 1.2 | 0.5-2,7 | .662 |

| Platinum and taxane based | 2.4 | 1.1-4.9 | .021 | 2.9 | 1.3-6.5 | .010 |

| Cyclophosphamide and adriamycin based | 2.3 | 1.2-4.5 | .012 | 1.2 | 0.5-2.6 | .728 |

| Targeted therapy and others regimen | 2.0 | 1.3-3.0 | .002 | 1.4 | 0.9-2.4 | .160 |

| Other Chinese medicine | ||||||

| ShenqiFuzheng injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 1.1 | 0.8-1.5 | .477 | 1.2 | 0.8-1.9 | .389 |

| Glycopeptide injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.7-1.4 | .965 | 1.1 | 0.7-1.7 | .756 |

| Kushen injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.7-1.5 | .975 | 1.0 | 0.6-1.7 | .899 |

| Shenmai injection | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.6-1.8 | .878 | 1.4 | 0.7-2.8 | .365 |

| DiyuShengbai tablet | ||||||

| No | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Yes | 1.8 | 1.0-3.5 | .067 | 1.6 | 0.4-4.0 | .328 |

| Chemotherapy cycles | ||||||

| 1-3 | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| >3 | 2.2 | 1.5-3.1 | <.001 | 3.0 | 2.0-4.6 | <.001 |

| Dosage | ||||||

| No Aidi use | [reference] | [reference] | ||||

| Less than conventional dosage (20-50 mL per day) | 2.3 | 1.2-4.4 | .014 | 2.8 | 1.4-5.6 | .004 |

| Conventional dosage (50-100 mL per day) | 3.1 | 2.2-4.4 | <.001 | 3.6 | 2.5-5.1 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Boldfaced P values are statistically significant.

Effect of Different Dosage of Aidi Injection

According to the instructions, the conventional dosage of Aidi injection for adults is 50 to 100 mL per day. Yet in our research, a subset of patients had used Aidi injection at less than conventional dosage in actual clinical use (20-50 mL). To understand the association between the dosages of Aidi injection and QoL, we further classified patients into three subgroups (conventional dosage group, less than conventional dosage group and non-Aidi group) according to the actual dosage of Aidi injection. Compared with non-Aidi injection, we found that the adjusted OR for PS is 2.8 (95% CI 1.4-5.6; P = .004) among the patients who used Aidi injection at less than the conventional dosage and 3.6 (95% CI 2.5-5.1; P < .001) in the conventional dosage group, which suggested that conventional dosage of Aidi injection might have had a better effect on PS (Table 7). According to this result, a subgroup analysis was then performed to further investigate the effect of different dosage on patients with different characteristics. As showed in Table 8, in almost all subgroups, the conventional dosage of Aidi injection showed more benefit in PS on patients compared to the other 2 groups. Besides, in comparison with the non-Aidi group, using the conventional dosage of Aidi injection decreased the incidence rate of all types of chemotherapy-related toxicity. However, using Aidi injection with less than conventional dosage had a poor effect on reducing incidence rate of chemotherapy-related toxicity (only showing significant difference in leukopenia compared with the non-Aidi group) (Table 9). In addition, the proportion of patients with improved PS was higher in the conventional dosage group, which was statistically different from the other 2 groups (Table 9). These results revealed that conventional dosage of Aidi injection had a better effect in improving PS and decreasing toxicity, that is, it was more beneficial to QoL of cancer patients.

Table 8.

Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% CI of Performance Status Benefit Associated With Different Dosage of Aidi Injection in the Stratified Analysis.

| Non-Aidi Use (N = 1600) |

Aidi Use |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less Than Conventional Dosage (n = 183) |

Conventional Dosage (n = 1417) |

||||

| OR | OR (95% CI) | P a | OR (95% CI) | P a | |

| Variable | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | [reference] | 2.0 (0.6-5.9) | .238 | 2.2 (1.7-2.9) | <.001 |

| Male | [reference] | 1.2 (1.1-1.6) | <.001 | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | <.001 |

| Age, years | |||||

| ⩽60 | [reference] | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | <.001 | 2.0 (1.6-2.6) | <.001 |

| >60 | [reference] | 1.7 (0.6-4.5) | .297 | 1.6 (1.2-2.0) | <.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||||

| <18.5 | [reference] | 4.4 (0.8-25.3) | .094 | 2.9 (1.5-5.0) | <.001 |

| 18.5-24 | [reference] | 2.6 (1.3-5.4) | .009 | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | <.001 |

| >24 | [reference] | 1.3 (0.9-4.3) | .252 | 2.1 (1.4-3.2) | <.001 |

| Tumor type | |||||

| Gastric cancer | [reference] | 6.0 (2.4-15.0) | <.001 | 2.1 (1.4-2.9) | <.001 |

| Lung cancer | [reference] | 1.1 (0.2-4.9) | .912 | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) | .029 |

| Breast cancer | [reference] | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | <.001 | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) | .002 |

| Colorectal cancer | [reference] | 1.4 (0.9-3.3) | .792 | 1.8 (1.1-3.6) | <.001 |

| Cardiac and esophageal cancer | [reference] | 12.1 (0.9-143.0) | .057 | 3.0 (1.0-8.9) | .042 |

| Hepatobiliary cancer | [reference] | 1.3 (0.6-9.7) | .891 | 0.8 (0.3-1.8) | 0.591 |

| Ovarian cancer | [reference] | 2.2 (1.6-3.3) | .042 | 2.5 (1.1-5.6) | .026 |

| TNM stage | |||||

| I-II | [reference] | 2.1 (0.4-10.2) | .357 | 1.7 (1.1-2.5) | .009 |

| III-IV | [reference] | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | <.001 | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | <.001 |

| Node metastasis | |||||

| Negative | [reference] | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | <.001 | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | <.001 |

| Positive | [reference] | 0.9 (0.1-7.4) | .936 | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) | <.001 |

| Distant metastasis | |||||

| Negative | [reference] | 1.3 (1.2-1.6) | .018 | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | <.001 |

| Positive | [reference] | 1.3 (0.2-11.0) | .782 | 1.4 (0.9-2.2) | .145 |

| Prior chemotherapy | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.4 (0.5-3.8) | .476 | 1.7 (1.3-2.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 3.7 (1.5-9.2) | .004 | 1.9 (1.5-2.5) | <.001 |

| ECOG score | |||||

| 0-1 | [reference] | 1.4 (1.3-1.7) | <.001 | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | <.001 |

| ⩾2 | [reference] | 0.9 (0.3-1.6) | .496 | 1.2 (0.5-2.6) | .733 |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.4 (1.2-1.9) | <.001 | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 2.0 (0.4-9.7) | .395 | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) | .181 |

| Renal insufficiency | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.4 (1.3-1.7) | <.001 | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | .797 | 0.8 (0.2-2.8) | .731 |

| Hepatic insufficiency | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.4 (1.3-4.7) | .008 | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 1.1(0.9-2.9) | .594 | 1.4 (0.8-2.6) | .265 |

| Diabetes | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | <.001 | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 0.6 (0.4-1.9) | .395 | 0.8 (0.4-1.6) | .484 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | |||||

| Platinum and fluorouracil based | [reference] | 3.5 (1.4-8.7) | .006 | 1.8 (1.4-2.4) | <.001 |

| Platinum and pemetrexed based | [reference] | 6.7 (1.0-46.0) | .054 | 2.2 (1.1-4.2) | .018 |

| Irinotecan and fluorouracil based | [reference] | 3.2 (0.6-17.6) | .185 | 1.2 (1.0-1.8) | .042 |

| Platinum and taxane based | [reference] | 2.8 (1.1-4.9) | .045 | 3.2 (1.1-9.2) | .033 |

| Cyclophosphamide and adriamycin based | [reference] | 1.7 (1.3-3.4) | .037 | 2.5 (1.2-5.6) | .019 |

| Targeted therapy and others regimen | [reference] | 0.5 (0.1-4.1) | .542 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | .002 |

| Other Chinese medicine | |||||

| ShenqiFuzheng injection | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | <.001 | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 1.8 (0.8-4.2) | .152 | 1.9 (1.4-2.6) | <.001 |

| Glycopeptide injection | |||||

| No | [reference] | 2.4 (1.1-5.0) | .026 | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 2.1 (0.6-7.5) | .275 | 1.9 (1.3-2.6) | <.001 |

| Kushen injection | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.9 (0.9-4.1) | .083 | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 5.5 (1.3-22.3) | .018 | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) | .038 |

| Shenmai injection | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.5 (1.2-1.7) | <.001 | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 3.2 (1.6-7.2) | .042 | 3.9 (1.4-10.9) | .009 |

| DiyuShengbai tablet | |||||

| No | [reference] | 1.3 (1.2-1.7) | .011 | 1.7 (1.5-2.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | [reference] | 1.7 (1.2-4.8) | .023 | 2.5 (1.1-7.2) | <.001 |

| Chemotherapy cycle | |||||

| 1-3 | [reference] | 1.3 (0.4-3.8) | .631 | 1.7 (1.4-2.2) | <.001 |

| >3 | [reference] | 4.1 (1.7-9.6) | .001 | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Boldfaced P values are statistically significant.

Table 9.

Effects of Different Dosage of Aidi Injection on Chemotherapy-Related Toxicity and Performance Status.

| Non-Aidi Group |

Aidi Group |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 1600), n (%) | Less Than Conventional Dosage (n = 183), n (%) | Conventional Dosage (n = 1417), n (%) | |

| Toxicity | |||

| AST elevation | 213 (13.3) | 27 (9.6) | 127 (8.9)a,b |

| ALT elevation | 276 (17.3) | 31 (16.9) | 152 (10.7)a,b |

| CR elevation | 79 (4.9) | 8 (4.4) | 36 (2.7)b |

| Nausea, vomiting | 756 (47.2) | 67 (36.6) | 527 (37.0)a,b |

| Diarrhea | 167 (10.4) | 18 (8.2) | 76 (5.4)a,b |

| Constipation | 120 (7.5) | 16 (8.7) | 77 (5.3)a |

| Allergy | 96 (6.0) | 8 (4.4) | 56 (4.0)a |

| Leucopenia | 490 (30.6) | 41 (22.4)a | 338 (23.9)a |

| Neutropenia | 393 (24.6) | 43 (23.4) | 305 (21.5)a |

| Thrombocytopenia | 235 (14.7) | 18 (9.8) | 134 (9.4)a |

| Performance status | |||

| Deterioration | 59 (3.7) | 4, (2.2) | 2 (0.2)a,b |

| Stabilization | 1493 (93.3) | 167 (91.2)a | 1290 (91.0)a |

| Improvement | 48 (3.0) | 12 (6.6)a | 125 (8.8)a |

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CR, creatinine.

P < .05 compared with non-Aidi group.

P < .05 compared with Aidi group with less than conventional dosage.

Combined Medication Information

To explore the real clinical combined medication rules of Aidi injection and determine whether there was a difference in medication between the 2 groups, the prescriptions of patients during chemotherapy were collected. The 9 most commonly used kinds of Western medicines and 5 kinds of traditional Chinese medicines are listed in Table 10. Glucocorticoid, antiemetic drugs, painkillers, stomach drugs, antiallergic drugs, and Chinese medicines, which were mainly extracted from ginseng were the most commonly used drugs. Notably, there is no statistical difference between the two groups, which further showed that the difference in QoL between Aidi users and non-Aidi users could be attributed to the Aidi injection. As shown in Figure 4A and B, the highest frequency (except Aidi injection) of joint use were dexamethasone plus metoclopramide plus tropisetron both in the Aidi group and non-Aidi group (the stronger the link is in the figure, the higher the frequency of combined use).

Table 10.

Combined Medication Information.

| Aidi Injection Used |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1600) |

Yes (N = 1600) |

||||

| Drug | n | % | n | % | P |

| Dexamethasone | 1126 | 70.3 | 1112 | 69.5 | .589 |

| Metoclopramide | 1049 | 65.5 | 1037 | 64.8 | .656 |

| Tropisetron | 911 | 56.9 | 905 | 56.6 | .830 |

| Pantoprazole sodium | 706 | 44.1 | 703 | 43.9 | .915 |

| Omeprazole | 231 | 14.4 | 229 | 14.3 | .920 |

| Clonazepam | 179 | 11.2 | 163 | 10.2 | .360 |

| Cimetidine | 159 | 9.9 | 149 | 9.3 | .549 |

| Diphenhydramine | 185 | 11.6 | 191 | 11.9 | .742 |

| Tramadol | 143 | 8.9 | 139 | 8.7 | .803 |

| ShenqiFuzheng injection | 503 | 31.4 | 497 | 31.1 | .819 |

| Glycopeptide injection | 424 | 26.5 | 433 | 27.1 | .719 |

| Kushen injection | 255 | 15.9 | 268 | 16.8 | .534 |

| Shenmai injection | 123 | 7.7 | 123 | 7.7 | .999 |

| DiyuShengbai tablet | 50 | 3.1 | 65 | 4.1 | .154 |

Figure 4.

Analysis of association rules of combined drug use of (A) Aidi users and (B) non-Aidi users.

Discussion

In past years, clinical research attached increasing importance to QoL, and a large number of studies investigated QoL as an outcome of cancer treatment. Yet due to the restriction of the subjectivity, complexity, and adherence of patients and physicians, it is difficult to assess QoL in real-world treatment.23 Much research had indicated that PS is associated with QoL from different perspectives. As Moningi and Walker25 reported, patients with the worse PS are correlated with worse QoL. It was reported in another study that higher QoL is significantly associated with better PS, and in the lower the QoL, the lower the PS will be.24 Apart from PS, several reports had suggested that QoL and chemotherapy-related toxicity are significantly correlated.28,29 Based on this research, PS served as a major surrogate endpoint in the present study to assess QoL in cancer patients, with the incidence rate of chemotherapy-related toxicity supplied for supplementalevidence. The findings of our study suggested that Aidi injection combined with chemotherapy could decrease the incidence rate of chemotherapy-related toxicity and improve PS in patients as compared with chemotherapy alone, that is, Aidi injection could improve QoL in cancer patients.

In fact, PS refers to a patient’s ability to perform activities and functions that meet basic physical needs in the face of illness and is attempt to quantify cancer patient’s general well-being and activities of daily life, which are affected by various symptoms and immune functions.28-30 Our study has shown that Aidi injection could decrease the incidence rate of various symptoms caused by chemotherapy, including nausea, vomiting, and so on (Tables 3 and 4). This might be due to the ability of Aidi injection to support body energy, clearing away heat and toxicity. Additionally, immune function damage is a serious toxicity, including lower antitumor and anti-infective immunity induced by chemotherapy, and is a major factor influencing PS. According to several studies, Aidi injection could significantly increase the percentage of CD3+ cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and the CD4+/CD8+ T cells ratio of peripheral blood and reverse the Th1/Th2 shift. These results revealed that Aidi injection could enhance cellular immunity.31,32 In addition, many studies have also shown that ginseng, Astragaloside and Cantharidin have immune regulation functions, which indirectly confirms that Aidi injection might enhance PS through improving immune function.14-16

Generally speaking, confounding factors are the major problem inherent in observational studies, which can affect persuasiveness. Addressing these known and unknown confounders was carefully considered in the study design: PSM was conducted to group patients33 and the chemotherapy-related toxicities were then compared after PSM. Damage to liver and renal and gastrointestinal reactions that occurred during chemotherapy in the Aidi group were significantly less than that in the control group, as shown in Table 3. The 2 groups had statistically significant difference in the incidence rate of leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, particularly leukopenia and thrombocytopenia (P < .001, P = .033, and P < .001, respectively). This finding is probably because of Astrgaloside,16 one of the main ingredients of Aidi injection, which can promote the proliferation of bone-marrow stem cells. Apart from PSM, stratification and multivariate modeling were conducted to adjust the impact of confounding factors. The PS benefit of using Aidi injection remained consistent after adjustment for a large number of factors including age, gender, TNM stage, and other variables (Table 6). Regardless of gender, age, TNM stage, node metastasis, prior chemotherapy, baseline ECOG score, chemotherapy regimens, other Chinese medicines as well as different chemotherapy cycles, the PS benefit of Aidi injection was confirmed in the stratified analysis. By adjusting the model, the probability of false results is likely to be low, most interference of confounding factors can be eliminated, and the validity of our results can increase. Besides, this study suggests that patients taking Aidi injection in conventional dosages might experience a higher improvement rate of PS and lower incidence rate of chemotherapy-related toxicity compared to the non-Aidi group and the group receiving lower dosages. The benefit of Aidi injection for patients was further supported by this finding.

Our results showed that patients with gastric cancer had a lower improvement rate of PS in comparison with the patients with lung cancer, breast cancer, cardiac and esophageal cancer, as well as ovarian cancer. This is probably because 70.16% patients with gastric cancer in our study had gastric surgery before enrollment, which might result in various symptoms, including loss of body weight and malnutrition.34 The resulting symptoms could cause significant deterioration in their PS.35 Yet from the subgroup of gastric cancer in the stratified analysis, the improvement rate of PS in the Aidi group was significantly higher than that in the control group (OR = 3.7, 95% CI 1.9-7.2). This suggests that patients with gastric cancer could benefit from Aidi injection, although gastric cancer is a factor associated with worse PS. This benefit might be attributed to inclusion of Ciwujia (Eleutherococcus senticosus) among the main ingredients of Aidi injection,8 which has been shown to replenish the vital essence and alleviate poor appetite.36 These results revealed that patients with gastric cancer could benefit from using Aidi injection compared with non-Aidi-users.

Hepatic insufficiency caused by chronic liver disease or liver metastasis, a poor prognostic factor for cancer patients, was found in 518 patients in the study group.37-41 In our study, the result of presence of hepatic insufficiency substantially inhibited any gains (OR = 0.5, 95% CI 0.2-1.0) in PS compared with normal liver function. Because of the protective effect of Astragaloside on liver injury,16,42,43 Aidi injection reduced the incidence rate of liver injury (Table 3). Still, patients using Aidi injection showed no advantages in the improvement rate of PS in comparison with the patients not using Aidi injection in the hepatic insufficiency subgroup (Figure 3). Besides, in the Aidi group, patients with hepatic insufficiency show no significant difference compared with those with normal liver function (OR = 0.5, 95%CI 0.2-1.8, P < .001) (Table 7). Hepatic insufficiency, which affects the detoxification and metabolic functions of the liver, might also alter the effect of Aidi injection. Unfortunately, the specific reasons still need further exploration because of the complex effective components of TCM. Given this problem, we are making preparation to conduct further relevant study on Aidi injection and liver injury, to supplement clinical evidence.

In this study, to explore the information of the combined medication of Aidi injection, the prescriptions of patients receiving chemotherapy were collected (Table 10). By conducting the association rule model,44 we found there was no significant difference in the drug combination between Aidi users and non-Aidi users (Figure 4A and B). Thus, we further demonstrated that the difference in QoL between the 2 groups was the effect of Aidi injection. Based on this model, thousands of combined medication rules were revealed and it was difficult to compare the impact of these rules of drug use on QoL. In a follow-up study, we will pay more attention to the most effective combination of Aidi injection. Yet our research has shown Aidi injection as the main factor on QoL and demonstrated the clinical effect of the combined medication of Aidi injection, which might be meaningful for clinical rational drug use.

The strengths of the present study consist of the large sample size and the fact that we had collected more detailed information, inclusive of routine blood work, blood biochemistry and combined medication information before and after treatment. Its size and the fact that it was extracted from real-world data provide a robust profile of PS for these patients in conditions of usual clinical practice. The findings of this study suggested a positive causal link between Aidi injection and the QoL of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. It is reasonably assumed that this integrative approach might be recommended to patients.

Limitations of our study were a result of the retrospective design. First and foremost, the findings were limited by potential and unrecognized confounding factors, for example, drinking and smoking. Yet these are considered unimportant factors determining patients’ entry into the cohort groups. Second, our data were collected from EMR database in hospital, where some problems remained. Because of the mobility of patients in large hospitals and limited time of follow-up, the outcome of survival time could not be explored in this study. Third, patients with longer hospitalization days (eg, longer chemotherapy cycle) have a better chance to use Aidi injection. Although we strive to conquer this problem by matching the baseline characteristics and apply logistic regression model to adjust all of the covariates in 2 groups, we cannot overstate the findings. However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is still the largest observational study to investigate the effectiveness of Aidi injection for patients with different types of cancer who receiving chemotherapy on the basis of real-world data, which might provide robust evidence.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study showed that Aidi injection as adjuvant to chemotherapy might improve the QoL in cancer patients by improving PS and reducing incident rate of chemotherapy-related toxicity. In addition, because of excellent effect of Aidi injection on patients with different types of cancer, it should be recommended to apply in clinical work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants. Thanks to the clinical pharmacists of the Department of Pharmacy of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University for their support of this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Jeong WS, Jun M, Kong AN. Nrf2: a potential molecular target for cancer chemoprevention by natural compounds. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, et al. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2097-2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:48-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lv C, Shi C, Li L, Wen X, Xian CJ. Chinese herbal medicines in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2018;12:174-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ling CQ, Yue XQ, Ling C. Three advantages of using traditional Chinese medicine to prevent and treat tumor. J Integr Med. 2014;12:331-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiao Z, Wang C, Li L, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of Aidi injection plus docetaxel-based chemotherapy in advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:7918258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiancheng W, Long G, Ye Z, et al. Effect of Aidi injection plus chemotherapy on gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Tradit Chin Med. 2015;35:361-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang T, Nan H, Zhang C, et al. Aidi injection combined with FOLFOX4 chemotherapy regimen in the treatment of advanced colorectal carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10(suppl 1):52-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu L, Liang J, Deng X. Effects of Aidi injection (艾迪注射液) with Western medical therapies on quality of life for patients with primary liver cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online January 15, 2018]. Chin J Integr Med. doi: 10.1007/s11655-017-2426-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang D, Wu J, Liu S, Zhang X, Zhang B. Network meta-analysis of Chinese herbal injections combined with the chemotherapy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X, Jin W, Fang B, et al. Aidi injection combined with CHOP chemotherapy regimen in the treatment of malignant lymphoma: a meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(suppl):11-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ge L, Mao L, Tian JH, et al. Network meta-analysis on selecting Chinese medical injections in radiotherapy for esophageal cancer [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2015;40:3674-3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cichello SA, Yao Q, Dowell A, Leury B, He XQ. Proliferative and inhibitory activity of Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus) extract on cancer cell lines; A-549, XWLC-05, HCT-116, CNE and Beas-2b. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:4781-4786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahuja A, Kim JH, Kim JH, Yi YS, Cho JY. Functional role of ginseng-derived compounds in cancer. J Ginseng Res. 2018;42:248-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li HC, Xia ZH, Chen YF, et al. Cantharidin inhibits the growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells by suppressing autophagy and inducing apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:1829-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ren S, Zhang H, Mu Y, Sun M, Liu P. Pharmacological effects of Astragaloside IV: a literature review. J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;33:413-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma JJ, Liu HP. Efficacy of Aidi injection (艾迪注射液) on overexpression of P-glycoprotein induced by vinorelbine and cisplatin regimen in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Integr Med. 2017;23:504-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi Q, Diao Y, Jin F, Ding Z. Antimetastatic effects of Aidi on human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting epithelialmesenchymal transition and angiogenesis. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:131-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu XT, Song Y, Qin S, Wang LL, Zhou JY. Radio-sensitization of SHG44 glioma cells by Aidi injection in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1415-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang H, Zhou QM, Lu YY, Du J, Su SB. Aidi injection alters the expression profiles of microRNAs in human breast cancer cells. J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;31:10-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Padrnos L, Dueck AC, Scherber R, et al. Quality of life and disease understanding: impact of attending a patient-centered cancer symposium. Cancer Med 2015;4:800-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adamowicz K, Saad ED, Jassem J. Health-related quality of life assessment in contemporary phase III trials in advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;50:194-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tassinari D. Surrogate end points of quality of life assessment: have we really found what we are looking for? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Finkelstein DM, Cassileth BR, Bonomi PD, Ruckdeschel JC, Ezdinli EZ, Wolter JM. A pilot study of the Functional Living Index-Cancer (FLIC) Scale for the assessment of quality of life for metastatic lung cancer patients. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. Am J Clin Oncol. 1988;11:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moningi S, Walker AJ, Hsu CC, et al. Correlation of clinical stage and performance status with quality of life in patients seen in a pancreas multidisciplinary clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e216-e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, Garcia-Carbonero R, et al. Proxies of quality of life in metastatic colorectal cancer: analyses in the RECOURSE trial. ESMO Open. 2017;2:e000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu B, Zhou X, Wang Y, et al. Data processing and analysis in real-world traditional Chinese medicine clinical data: challenges and approaches. Stat Med. 2012;31:653-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Atkinson TM, Andreotti CF, Roberts KE, Saracino RM, Hernandez M, Basch E. The level of association between functional performance status measures and patient-reported outcomes in cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3645-3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laird BJ, Fallon M, Hjermstad MJ, et al. Quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: differential association with performance status and systemic inflammatory response. J Clin Oncol.10 2016;34:2769-2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bersanelli M, Brighenti M, Buti S, Barni S, Petrelli F. Patient performance status and cancer immunotherapy efficacy: a meta-analysis. Med Oncol. 2018;35:132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang Q, Chen DY. Effect of Aidi injection on peripheral blood expression of Th1/Th2 transcription factors and cytokines in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma during radiotherapy [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2009;29:394-397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xiao Z, Wang C, Sun Y, et al. Can Aidi injection restore cellular immunity and improve clinical efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy? A meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials following the PRISMA guidelines. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson SR, Tomlinson GA, Hawker GA, Granton JT, Feldman BM. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in observational studies of treatment effect. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terashima M, Tanabe K, Yoshida M, et al. Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45 and changes in body weight are useful tools for evaluation of reconstruction methods following distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(suppl 3):S370-S378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mangano A, Rausei S, Lianos GD, Dionigi G. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2015;262:e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang L, Zhao H, Huang B, Zheng C, Peng W, Qin L. Acanthopanax senticosus: review of botany, chemistry and pharmacology. Pharmazie. 2011;66:83-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tang LSY, Covert E, Wilson E, Kottilil S. Chronic hepatitis B infection: a review. JAMA. 2018;319:1802-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sabbagh C, Chatelain D, Nguyen-Khac E, Rebibo L, Joly JP, Regimbeau JM. Management of colorectal cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a retrospective, case-matched study of short- and long-term outcomes. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:429-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang YP, Chen YM, Lai CH, et al. The impact of de novo liver metastasis on clinical outcome in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sakamoto Y, Ohyama S, Yamamoto J, et al. Surgical resection of liver metastases of gastric cancer: an analysis of a 17-year experience with 22 patients. Surgery. 2003;133:507-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saiura A, Umekita N, Inoue S, et al. Clinicopathological features and outcome of hepatic resection for liver metastasis from gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1062-1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shahzad M, Shabbir A, Wojcikowski K, Wohlmuth H, Gobe GC. The antioxidant effects of Radix Astragali (Astragalus membranaceus and related species) in protecting tissues from injury and disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:1331-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu W, Gao FF, Li Q, et al. Protective effect of astragalus polysaccharides on liver injury induced by several different chemotherapeutics in mice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:10413-10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen W, Yang J, Wang HL, Shi YF, Tang H, Li GH. Discovering associations of adverse events with pharmacotherapy in patients with non–small cell lung cancer using modified Apriori algorithm. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1245616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]