ABSTRACT

The Caenorhabditis elegans aminophospholipid translocase TAT-1 maintains phosphatidylserine (PS) asymmetry in the plasma membrane and regulates endocytic transport. Despite these important functions, the structure–function relationship of this protein is poorly understood. Taking advantage of the tat-1 mutations identified by the C. elegans million mutation project, we investigated the effects of 16 single amino acid substitutions on the two functions of the TAT-1 protein. Two substitutions that alter a highly conserved PISL motif in the fourth transmembrane domain and a highly conserved DKTGT phosphorylation motif, respectively, disrupt both functions of TAT-1, leading to a vesicular gut defect and ectopic PS exposure on the cell surface, whereas most other substitutions across the TAT-1 protein, often predicted to be deleterious by bioinformatics programs, do not affect the functions of TAT-1. These results provide in vivo evidence for the importance of the PISL and DKTGT motifs in P4-type ATPases and improve our understanding of the structure–function relationship of TAT-1. Our study also provides an example of how the C. elegans million mutation project helps decipher the structure, functions, and mechanisms of action of important genes.

KEY WORDS: TAT-1, P4-ATPase, Million mutation project, Phosphatidylserine, C. elegans, Endocytic transport

Summary: The structure–function relationship of the C. elegans P4-ATPase TAT-1 and identification of two highly conserved motifs that are especially important for the TAT-1 phosphatidylserine flippase activity.

INTRODUCTION

The asymmetric distribution of phospholipids in the plasma membrane is essential for the maintenance of cell shape and cell physiology, and acts as a platform to regulate intracellular and extracellular signaling events (Bretscher, 1972; Op den Kamp, 1979). One of the phospholipids, phosphatidylserine (PS), is predominantly restricted to the cytosolic leaflet of living cells (Devaux, 1992; Daleke, 2003). The redistribution of PS in the plasma membrane occurs in some important biological events, such as blood coagulation, cell–cell fusion and apoptosis (Fadeel and Xue, 2009), and is triggered by activation of phospholipid scramblases and concomitant inactivation of aminophospholipid translocases (Bratton et al., 1997). The appearance of PS in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane serves as an ‘eat-me’ signal for phagocytosis (Fadok et al., 2001; Kagan et al., 2002). PS externalization during apoptosis is a widespread phenomenon, and the mechanisms that mediate apoptotic PS exposure appear to be conserved (Fadeel and Xue, 2009). Indeed, the worm apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) homolog, WAH-1, upon its release from mitochondria during apoptosis, promotes externalization of PS through activating phospholipid scramblase 1 (SCRM-1) (Wang et al., 2007), and evidence for a similar pathway of PS exposure in mammalian cells has been reported (Preta and Fadeel, 2012). Moreover, the C. elegans CED-8 protein and its mammalian homolog, XK-related protein 8 (XKR8), promote PS externalization upon their cleavage and activation by caspases (Chen et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2013), further testifying to the conservation of PS exposure pathways (Klöditz et al., 2017).

P4-type ATPases are highly conserved transmembrane proteins that are suggested to promote ATP-dependent inward movement of aminophospholipids such as PS (Auland et al., 1994; Tang et al., 1996; Paulusma and Oude Elferink, 2005; Andersen et al., 2016; Roland and Graham, 2016), resulting in the restriction of PS in the cytosolic leaflet and PS asymmetry in the plasma membrane. The mechanisms by which these large lipid substrates are transported specifically across the membrane have remained an enigma (Vestergaard et al., 2014; Andersen et al., 2016). TAT-1 is the first member of this protein family that has been demonstrated to play a critical role in maintaining PS asymmetry in the plasma membrane in vivo (Darland-Ransom et al., 2008), as loss of the TAT-1 activity leads to ectopic exposure of PS on the cell surface. Furthermore, caspase-mediated cleavage of the human P4-ATPase ATP11C was recently shown to trigger apoptotic PS exposure (Segawa et al., 2014). TAT-1 is predominantly localized at the plasma membrane (Darland-Ransom et al., 2008), but is also found on the membranes of early and recycling endosomes where PS is enriched on the cytosolic surface (Ruaud et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010). In intestinal cells, tat-1 loss-of-function mutants accumulate large vacuoles of mixed endolysosomal identities and exhibit disrupted PS asymmetry in the endosomal membranes (Ruaud et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010), indicating that tat-1 also regulates PS asymmetry in the endolysosomal membrane and endocytic trafficking.

Although the lipid-transporting functions of the TAT-1 protein and its human homologs are known, how these ATPases act to regulate membrane PS asymmetry and endocytic transport and the protein domains critical for these functions are poorly understood. The C. elegans million mutation project, which has uncovered over 800,000 unique single nucleotide variants (Thompson et al., 2013), provides a unique genetic resource for structure–function analyses of important proteins. As a proof-of-concept study, we analyzed the impact of 16 different missense mutations in the tat-1 gene on the functions of TAT-1 in C. elegans. Unexpectedly, most missense mutations do not affect either the function or the stability of the TAT-1 protein, despite being predicted as deleterious to the protein by three bioinformatics programs. However, three substitutions, including one at the highly conserved PISL motif of the fourth transmembrane domain and one at the highly conserved DKTGT phosphorylation motif in the intracellular domain that binds ATP, disrupt or reduce the functions of TAT-1, indicating that these domains are crucial for the functions of TAT-1. This is the first in vivo demonstration of the importance of these motifs for the activity of P4-ATPases in multicellular organisms.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

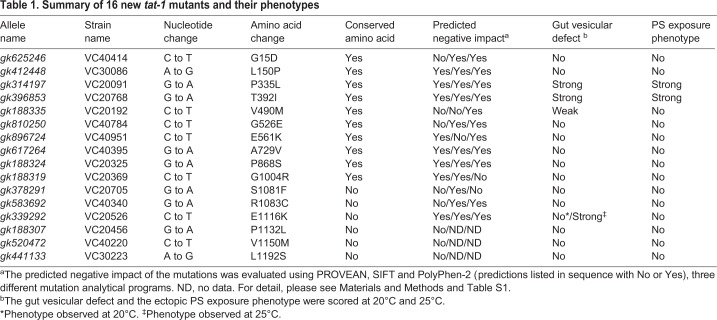

To investigate the effects of different tat-1 mutations on the endolysosomal transport function of TAT-1, we analyzed the vacuolar phenotype in the intestine of 16 tat-1 mutants summarized in Table 1. These single amino acid substitutions are distributed across the entire TAT-1 protein (Fig. 1A), including the transmembrane, intracellular and extracellular domains. Most mutations affect highly conserved amino acids, are substitutions of amino acids with different or opposite physicochemical properties, and are projected to be deleterious by three different bioinformatics programs commonly used for predicting the impact of missense mutations (Kumar et al., 2009; Adzhubei et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2012) (Table 1; Fig. S1, Table S1).

Table 1.

Summary of 16 new tat-1 mutants and their phenotypes

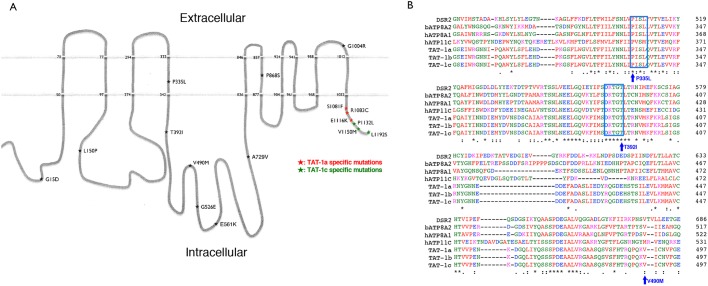

Fig. 1.

TAT-1 protein structure and location of the tat-1 mutations. (A) The schematic figure shows the structure of the TAT-1 protein with ten transmembrane domains. The positions of the analyzed TAT-1 mutations are indicated by stars. Numbers indicate mutated residues or the beginning and end of the putative transmembrane domains. The nature of the substitutions is also shown. Three mutations each alter TAT-1a and TAT-1c isoforms and are highlighted with red and green, respectively. (B) Amino acid alignment of a critical region essential for the proper TAT-1 functions. The protein sequences from three TAT-1 isoforms of C. elegans were aligned with those of P4-type ATPases from Drosophila (DSR2), cattle (ATP8A2) and humans (ATP8A1 and ATP11C). The highly conserved PISL and DKTGT motifs are shown in blue boxes. Three mutations that disrupt or reduce the functions of TAT-1 are indicated.

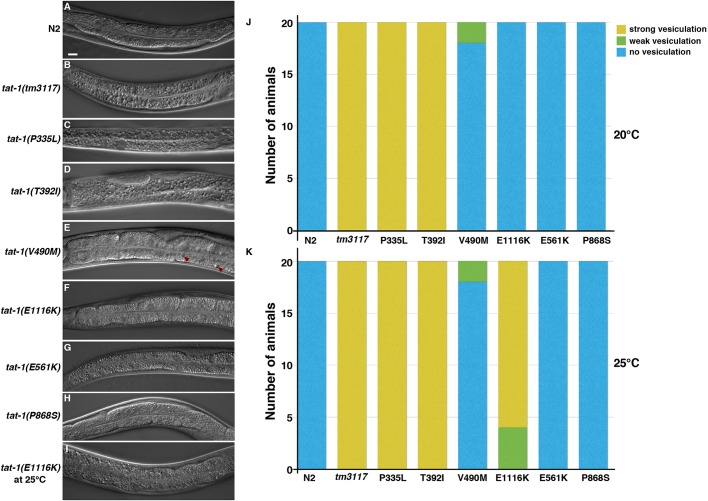

At normal growing temperature (20°C), unlike wild-type N2 animals (Fig. 2A), two of the tat-1 mutants, TAT-1(P335L) and TAT-1(T392I), showed a strong vesicular gut phenotype (Fig. 2C,D,J) similar to that seen in the loss-of-function tat-1(tm3117) deletion mutant (Fig. 2B; Fig. S1). A very weak vesicular phenotype was observed in the TAT-1(V490M) mutant (Fig. 2E,J). The other 13 tat-1 mutants displayed no obvious defect in their intestines (Fig. 2F–H,J; Fig. S2A–S). Incubation at 25°C revealed an additional, temperature-sensitive mutant (E1116K) that displayed a vesicular gut phenotype only at a higher temperature (compare Fig. 2I,K and Fig. 2F,J). Hence, most tat-1 mutations, despite drastic changes in the amino acids, do not seem to affect the endocytic transport function of TAT-1.

Fig. 2.

Vacuolar gut phenotypes of the tat-1 mutants. (A–I) Representative images of the intestines of two control strains (N2 and tm3117) and six tat-1 mutants at 20°C (A-H) or 25°C (I) are shown. Red arrowheads indicate the minor vesicular defect in the intestine. Scale bar: 10 μm for all images. (J,K) Gut vesiculation defects of the tat-1 mutants scored at 20°C (J) and 25°C (K) are shown (n=20). Yellow, green and blue indicate strong, weak and no defects, respectively.

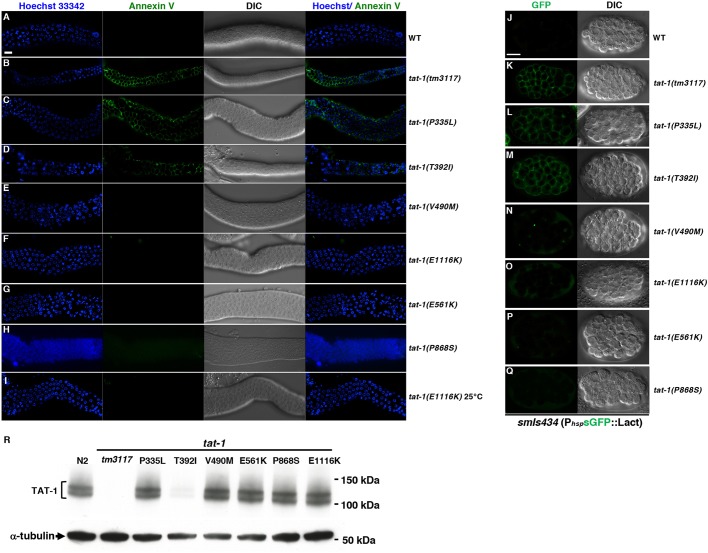

Next, to investigate whether the PS distribution in the plasma membrane is altered in the tat-1 mutants, we dissected gonads from adult animals and stained them ex vivo with the Alexa Fluor 488-labeled PS-binding protein annexin V (Wang et al., 2007). The tat-1(tm3117) mutant and the two tat-1 mutants (P335L and T392I) that exhibited a strong vesicular gut phenotype were the only mutants with annexin V labelling of the plasma membrane in most germ cells (Fig. 3B–D), indicating loss of plasma membrane PS asymmetry. All other mutants, including the TAT-1(V490M) mutant with a very weak gut defect, were negative for annexin V staining (Fig. 3E–H; Fig. S3A). Incubation at 25°C did not result in stronger PS exposure in the TAT-1(P335L) and TAT-1(T392I) mutants, or any detectable PS exposure in the other 14 tat-1 mutants (Table 1), including the TAT-1(E1116K) mutant that exhibited a temperature-sensitive gut phenotype (Fig. 3I). These results were confirmed in somatic cells using a genetically encoded PS sensor, a secreted GFP–lactadherin fusion protein (sGFP::Lact; Mapes et al., 2012) (Fig. 3J–Q).

Fig. 3.

PS staining and immunoblotting results of the tat-1 mutants. (A–I) Representative images of dissected gonads from the indicated animals stained with annexin V (green) to visualize externalized PS and Hoechst 33342 (blue) to show nuclei. DIC images of the gonads are also shown. N2 (wild-type) and tat-1(tm3117) strains were included as negative and positive controls, respectively. Images acquired at 20°C (A–H) and 25°C (l) are indicated. (J–Q) Representative images of smIs434 embryos carrying different tat-1 mutations stained for sGFP::Lact (left column) and the corresponding DIC images (right column). Scale bar: 10 μm for all images. (R) Immunoblotting was performed on whole-worm lysates from wild-type or different tat-1 mutant animals as indicated. The mouse monoclonal antibody 7G1 was used to detect TAT-1 proteins (1:1000 dilution). The expression of α-tubulin was used as a loading control. Representative results from at least six independent experiments are shown.

To confirm that the observed phenotypes (i.e. vacuolar gut phenotype and ectopic PS exposure) are due to loss of the tat-1 function, we generated transgenic animals expressing cDNA encoding the TAT-1a isoform under the control of the C. elegans heat shock promoter (PhspTAT-1a). Notably, expression of TAT-1a fully rescued the gut vacuolar phenotype of the TAT-1(P335L), TAT-1(T392I) and TAT-1(E1116K) mutants (Fig. S3B) and the ectopic PS exposure defect in somatic cells of the TAT-1(P335L) and TAT-1(T392I) mutants (Fig. S3C), indicating that the defects observed in these mutants are, indeed, caused by impaired tat-1 functions.

Since multiple tat-1 mutations affect highly conserved amino acids in this protein family (Table 1; Fig. S1) and were predicted to be deleterious to the protein (Table S1), we investigated whether the tat-1 mutations cause defects by destabilizing the TAT-1 protein. Immunoblotting experiments were performed on total lysates of the tat-1 mutants, and the expression levels of the TAT-1 proteins were analyzed using a monoclonal antibody to TAT-1. The TAT-1 proteins, present in multiple isoforms, could be detected in most of the tat-1 mutants at levels comparable to those of the wild-type animals (Fig. 3R). However, in the tat-1(tm3117) and tat-1(T392I) mutants, TAT-1 protein levels were greatly reduced, indicating that the T392I mutation and the tm3117 deletion have a negative impact on the stability or the expression of the TAT-1 proteins, leading to the loss of the protein expression. Interestingly, although the P335L mutation, altering the highly conserved PISL motif in the fourth transmembrane domain, caused a strong vesicular gut defect and ectopic PS exposure, this mutation did not affect TAT-1 expression and/or stability in vivo (Fig. 3R).

Our study has provided important and new insights into the structure and functions of the TAT-1 protein. Most TAT-1 mutations, surprisingly, were found not to affect the function or stability of the TAT-1 protein (Table 1; Fig. 3R), despite the fact that they alter highly conserved amino acids and the predictions that they would negatively impact the function of the protein (Table S1). These include the L150P, P868S, and P1132L mutations, which likely change the local secondary structures of the protein, due to the conformational rigidity of the proline residue, with all three bioinformatics programs projecting L150P and P868S to be deleterious (Table S1). The G15D, G526E, E561K and G1004R mutations result in substitutions of amino acids by ones with very different or opposite physicochemical properties and are predicted to be deleterious by two of the three programs (Table S1). However, they do not compromise the TAT-1 functions. These observations, therefore, suggest that the TAT-1 protein is rather stable and can withstand local residue alterations or secondary structure changes. The finding that TAT-1 can tolerate multiple predicted deleterious mutations cautions against the overreliance on bioinformatics tools to predict the functional impact of missense mutations.

Three mutations each alter the intracellular C-termini of the TAT-1a and TAT-1c isoforms, respectively, and show no detectable effect on the functions of TAT-1, with the exception of the E1116K mutation, suggesting that the C-terminus of TAT-1 may not be crucial for its functions. On the other hand, our in vivo study has identified two highly conserved motifs, the PISL motif in the fourth transmembrane domain and the DKTGT phosphorylation motif in the following intracellular domain, to be especially important for the flippase activity of TAT-1. The conserved DKTGT phosphorylation motif is found in all P4-type ATPases (Fig. 1B) and is thought to be critical for the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation catalytic cycle that results in structural changes of the protein and translocation of the lipid substrate (Okamura et al., 2003; Andersen et al., 2016). In addition, mutations in this motif could destabilize the protein, as a D454A mutation in the DKTGT motif of ATP8B1, altering the phosphorylation site D454, destabilized the protein, which was suppressed by incubation with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Folmer et al., 2009). Consistent with this observation, the T392I mutation, altering the final residue of this motif, disrupts the functions of TAT-1 through destabilizing the TAT-1 protein (Fig. 3R). On the other hand, the P335L mutation alters the first residue of a highly conserved PISL motif in the fourth transmembrane domain (M4). The M4 transmembrane domain, based on a modelled structure of the human P4 ATPase ATP8A2 and related mutational studies, is proposed to play a critical role in determining the specificity of the lipid substrate, with the isoleucine residue in the PISL motif contacting the head group of the phospholipid substrate and mediating its release to the cytoplasmic side and the M4 domain serving as a pump rod to move the phospholipid substrate (Andersen et al., 2016; Vestergaard et al., 2014; Roland and Graham, 2016). Interestingly, a missense mutation (I376M) in the PISL motif in ATP8A2 was found to cause a neurodegenerative disorder in humans (Onat et al., 2013) and found to impair the ATPase and the PS flipping activity of ATP8A2 without affecting its expression or stability in cultured cells (Vestergaard et al., 2014), further highlighting the importance of this motif in P4 ATPases. This is consistent with the observation that the P335L mutation, altering the proline residue right before the isoleucine residue in the PISL motif, disrupts the functions of TAT-1, but does not affect TAT-1 expression or stability (Table 1; Fig. 3R).

Notably, our study has shown that TAT-1 mutations either disrupt both functions of TAT-1 (P335L and T392I) or do not affect TAT-1, with the possible exception of the V490M mutation, which only causes a very mild endocytic defect, and the E1116K mutation, which only causes a temperature-sensitive endocytic defect. These observations are consistent with the finding that TAT-1 is important for maintaining PS asymmetry in both the plasma membrane and the endosomal membrane, the latter of which is important for proper endocytic transport (Darland-Ransom et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010). Thus, the function of TAT-1 in endocytic sorting and its role in maintaining PS asymmetry in the plasma membrane are closely linked. On the other hand, TAT-1 may interact with different factors, some of which could be cell type specific, to regulate PS asymmetry in the plasma membrane and in the endosomal membrane, respectively, which may account for the endocytic-specific defect observed in the TAT-1(V490M) and TAT-1(E1116K) mutants. In this case, these two mutations may present useful tools to identify these factors through genetic approaches, such as enhancer or suppressor screens, or biochemical methods, including co-immunoprecipitation experiments.

Cells invest a considerable amount of energy to ensure that most of the plasma membrane aminophospholipids, including PS, are oriented toward the cytoplasm (Balasubramanian and Schroit, 2003). However, there is still a lack of mechanistic understanding of how phospholipid asymmetry is achieved and maintained. Here, we utilize the mutational resource of the C. elegans million mutation project to investigate the structure–function relationship of the TAT-1 protein using a combination of genetic, cell biological, bioinformatics and functional analyses. These studies reveal residues and regions of TAT-1 that are critical for maintaining plasma membrane PS asymmetry in vivo, and underscore the utility of the million mutation project for structure-function analyses of important proteins. Our study also stresses the importance of in vivo verification of bioinformatics predictions of deleterious missense mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans wild-type and mutant strains

The N2 Bristol strain obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center was used as the wild-type strain. The strain and allele information of the tat-1 mutants from the C. elegans million mutation project are listed in Table 1 and all mutations analyzed were confirmed by sequencing. The tat-1(tm3117) deletion mutation was isolated from TMP/UV mutagenized worms (Gengyo-Ando and Mitani, 2000). smIs434 is an integrated transgene strain expressing the in vivo PS sensor, sGFP::Lact (Mapes et al., 2012). All C. elegans strains were cultured and maintained at 20°C or 25°C on nematode growth medium plates inoculated with Escherichia coli OP50.

Intestinal vacuolization phenotype assay

Worms were allowed to develop to larval stage 4 (L4) at 20°C or 25°C and then mounted on glass slides with a 1% agar pad. The vesicular gut phenotype was assessed using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Normally 20 animals were scored at each temperature for vacuolization phenotype.

Annexin V staining on dissected gonads

PS staining ex vivo on dissected gonads of adult animals was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2007). Briefly, adult animals were placed into a depression slide and paralyzed with 1 mM levamisole (L9756, Sigma). Gonads were gently dissected from 1-day-old adult hermaphrodites by cutting them at the head region. In order to prevent drying of the gonads, animals were kept in a gonad dissection buffer (60 mM NaCl, 32 mM KCl, 3 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, 50 µg/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, 10 mM glucose, 33% fetal calf serum and 2 mM CaCl2). The exposed gonads were washed once in the dissection buffer and transferred to dissection buffer containing 1 µl of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated annexin V (Molecular Probes) and 4 µM of Hoechst 33342. After a 45 min incubation in the dark, gonads were washed with dissection buffer, placed on a 1% agarose pad and visualized using a 40× objective of a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. Fluorescence and DIC images were captured using a CCD camera (PCO SensiCam) operating with Slidebook 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations).

PS staining of somatic cells in embryos

smIs434 adult transgenic animals carrying the tat-1 mutations were allowed to lay eggs on plates for 2 h before they were removed. The plates with eggs were placed at 33°C for 45 min and returned to 20°C for recovery at room temperature for 2 h. Pre-comma or comma stage embryos were then mounted on glass slides with 1% agar pads and examined by a 100X objective from an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with epifluorescence (Mapes et al., 2012).

Rescue of tat-1 mutants

Full-length TAT-1a cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR using total RNA extracted from N2 animals as templates. The following primers were used: sense primer, 5′-GCGCTAGCATGCCCACAGAGGCAAGAG-3′ and antisense primer, 5′-GATCCCGGGTTATCGTCCAGTCGGTTTTTC-3′. The amplified TAT-1a cDNA was digested with NheI and SmaI and subcloned into the pPD49.83 vector through its NheI and EcoRV sites. The resulting plasmid, PhspTAT-1a, and the injection marker, Psur5mCherry, were injected into smIs434 young adults carrying the tat-1 mutations at concentrations of 25 ng/µl each. To examine rescue of the ectopic PS exposure defect in the tat-1 mutants, smIs434 embryos carrying the tat-1 mutation and the PhspTAT-1a transgenic array were incubated at 33°C for 45 min, allowed to recover at 20°C for 2 h, and then imaged using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with epifluorescence. To examine rescue of the vacuolar gut defect in the tat-1 mutants, smIs434 embryos carrying the tat-1 mutation and the PhspTAT-1a transgenic array were incubated at 33°C for 45 min, allowed to recover at 20°C until they reached the L1 stage, heat shocked again at 33°C for 45 min, and returned to 20°C until they reached the L4 stage when they were imaged.

Generation of mouse monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies to TAT-1 were raised in mice using a subcutaneous injection of 150 μg of the purified recombinant TAT-1 protein (amino acid 369–734, designated as rTat-S2 protein and expressed and purified from Escherichia coli) emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant, followed by an intravenous booster injection of 50 μg of rTat-S2 two weeks later. The resulting hybridomas were screened for secretion of monoclonal antibodies specific to rTat-S2 using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Monoclonal antibodies were prepared by injecting hybridoma cultures into the peritoneal cavities of pristane-primed BALB/c mice. The antibodies were purified from the collected ascites using ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by Mabselect-Xtral affinity chromatography (Amersham GE Health). Immunoglobulin concentrations were determined on a DU800 spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulters). One monoclonal antibody, designated 7G1, was used here.

Western blot analysis of TAT-1 expression

7G1 monoclonal antibody (described above) was used to detect the expression levels of the TAT-1 proteins in C. elegans lysates (1:1000 dilution). A mouse monoclonal antibody, AA4.3, was used to detect the expression level of α-tubulin as a loading control (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, no. 12G10, 1:3000 dilution). A goat-anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was used as the secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, no. 115-035-008, 1:10,000 dilution).

Bioinformatics analyses of tat-1 mutations

Three different bioinformatics programs, PROVEAN, SIFT and PolyPhen-2, were used to predict the impact of various amino acid substitutions on the functions of the TAT-1 protein. Briefly, if PROVEAN produces a value of less than or equal to −2.5, the substitution is determined to be ‘deleterious’. If the value is greater than −2.5, the substitution is likely to be ‘neutral’ (Choi et al., 2012). For SIFT, a score of 0.05 or below indicates that the substitution is ‘not tolerated’ (Kumar et al., 2009). In the PolyPhen-2 analysis, if the final composite score is equal to or greater than 0.97, the substitution is considered ‘probably damaging’. If between 0.65–0.97, it is considered ‘possibly damaging’, and if it is <0.65, it is classified as ‘benign’ (Adzhubei et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Y.-Z.C., K.K., B.F., D.X.; Methodology: Y.-Z.C., K.K., E.-S.L., Q.Y., J.J., Y.L.-y., S.M., N.-S.X., B.F., D.X.; Validation: Y.-Z.C., K.K., E.-S.L., D.P.N., Q.Y., J.J., Y.L.-y., A.H.; Formal analysis: Y.-Z.C., K.K., E.-S.L., Q.Y., J.J., Y.L.-y., S.M., B.F., D.X.; Investigation: Y.-Z.C., K.K., E.-S.L., Q.Y., J.J., Y.L.-y., S.M., B.F., D.X.; Resources: B.F., D.X.; Data curation: Y.-Z.C., K.K., E.-S.L., Q.Y., J.J., Y.L.-y., A.H., B.F., D.X.; Writing: Y.-Z.C., K.K., B.F., D.X. Visualization: Y.-Z.C., K.K., E.-S.L., B.F., D.X.; Supervision: B.F., D.X.; Project administration: B.F., D.X.; Funding: B.F., D.X.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35 GM118188 (to D.X.) and by the Swedish Research Council (to B.F.). K.K. acknowledges the Erik and Edith Fernström Foundation for Medical Research for funding the student exchange programme between Stockholm and Boulder, CO. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.227660.supplemental

References

- Adzhubei I. A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L., Ramensky V. E., Gerasimova A., Bork P., Kondrashov A. S. and Sunyaev S. R. (2010). A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7, 248-249. 10.1038/nmeth0410-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. P., Vestergaard A. L., Mikkelsen S. A., Mogensen L. S., Chalat M. and Molday R. S. (2016). P4-ATPases as phospholipid flippases-structure, function, and enigmas. Front. Physiol. 7, 275 10.3389/fphys.2016.00275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auland M. E., Roufogalis B. D., Devaux P. F. and Zachowski A. (1994). Reconstitution of ATP-dependent aminophospholipid translocation in proteoliposomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10938-10942. 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K. and Schroit A. J. (2003). Aminophospholipid asymmetry: a matter of life and death. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 701-734. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton D. L., Fadok V. A., Richter D. A., Kailey J. M., Guthrie L. A. and Henson P. M. (1997). Appearance of phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells requires calcium-mediated nonspecific flip-flop and is enhanced by loss of the aminophospholipid translocase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26159-26165. 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher M. S. (1972). Asymmetrical lipid bilayer structure for biological membranes. Nat. New Biol. 236, 11-12. 10.1038/newbio236011a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Jiang Y., Zeng S., Yan J., Li X., Zhang Y., Zou W. and Wang X. (2010). Endocytic sorting and recycling require membrane phosphatidylserine asymmetry maintained by TAT-1/CHAT-1. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001235 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-Z., Mapes J., Lee E.-S., Skeen-Gaar R. R. and Xue D. (2013). Caspase-mediated activation of Caenorhabditis elegans CED-8 promotes apoptosis and phosphatidylserine externalization. Nat. Commun. 4, 2726 10.1038/ncomms3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Sims G. E., Murphy S., Miller J. R. and Chan A. P. (2012). Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE 7, e46688 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daleke D. L. (2003). Regulation of transbilayer plasma membrane phospholipid asymmetry. J. Lipid Res. 44, 233-242. 10.1194/jlr.R200019-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darland-Ransom M., Wang X., Sun C. L., Mapes J., Gengyo-Ando K., Mitani S. and Xue D. (2008). Role of C. elegans TAT-1 protein in maintaining plasma membrane phosphatidylserine asymmetry. Science 320, 528-531. 10.1126/science.1155847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux P. F. (1992). Protein involvement in transmembrane lipid asymmetry. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 21, 417-439. 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadeel B. and Xue D. (2009). The ins and outs of phospholipid asymmetry in the plasma membrane: roles in health and disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 44, 264-277. 10.1080/10409230903193307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok V. A., de Cathelineau A., Daleke D. L., Henson P. M. and Bratton D. L. (2001). Loss of phospholipid asymmetry and surface exposure of phosphatidylserine is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages and fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1071-1077. 10.1074/jbc.M003649200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer D. E., van der Mark V. A., Ho-Mok K. S., Oude Elferink R. PJ. and Paulusma C. C. (2009). Differential effects of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 1 and benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 1 mutations on canalicular localization of ATP8B1. Hepatology 50, 1597-1605. 10.1002/hep.23158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengyo-Ando K. and Mitani S. (2000). Characterization of mutations induced by ethyl methanesulfonate, UV, and trimethylpsoralen in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 64-69. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan V. E., Gleiss B., Tyurina Y. Y., Tyurin V. A., Elenstrom-Magnusson C., Liu S.-X., Serinkan F. B., Arroyo A., Chandra J., Orrenius S. et al. (2002). A role for oxidative stress in apoptosis: oxidation and externalization of phosphatidylserine is required for macrophage clearance of cells undergoing Fas-mediated apoptosis. J. Immunol. 169, 487-499. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöditz K., Chen Y.-Z., Xue D. and Fadeel B. (2017). Programmed cell clearance: from nematodes to humans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482, 491-497. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Henikoff S. and Ng P. C. (2009). Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1073-1081. 10.1038/nprot.2009.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapes J., Chen Y.-Z., Kim A., Mitani S., Kang B.-H. and Xue D. (2012). CED-1, CED-7, and TTR-52 regulate surface phosphatidylserine expression on apoptotic and phagocytic cells. Curr. Biol. 22, 1267-1275. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H., Yasuhara J. C., Fambrough D. M. and Takeyasu K. (2003). P-type ATPases in Caenorhabditis and Drosophila: implications for evolution of the P-type ATPase subunit families with special reference to the Na,K-ATPase and H,K-ATPase subgroup. J. Membr. Biol. 191, 13-24. 10.1007/s00232-002-1041-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onat O. E., Gulsuner S., Bilguvar K., Nazli Basak A., Topaloglu H., Tan M., Tan U., Gunel M. and Ozcelik T. (2013). Missense mutation in the ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter protein ATP8A2 is associated with cerebellar atrophy and quadrupedal locomotion. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 21, 281-285. 10.1038/ejhg.2012.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Op den Kamp J. AF. (1979). Lipid asymmetry in membranes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 48, 47-71. 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.000403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulusma C. C. and Oude Elferink R. PJ. (2005). The type 4 subfamily of P-type ATPases, putative aminophospholipid translocases with a role in human disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1741, 11-24. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preta G. and Fadeel B. (2012). AIF and Scythe (Bat3) regulate phosphatidylserine exposure and macrophage clearance of cells undergoing Fas (APO-1)-mediated apoptosis. PLoS ONE 7, e47328 10.1371/journal.pone.0047328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland B. P. and Graham T. R. (2016). Decoding P4-ATPase substrate interactions. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 51, 513-527. 10.1080/10409238.2016.1237934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruaud A. F., Nilsson L., Richard F., Larsen M. K., Bessereau J. L. and Tuck S. (2009). The C. elegans P4-ATPase TAT-1 regulates lysosome biogenesis and endocytosis. Traffic 10, 88-100. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00844.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segawa K., Kurata S., Yanagihashi Y., Brummelkamp T. R., Matsuda F. and Nagata S. (2014). Caspase-mediated cleavage of phospholipid flippase for apoptotic phosphatidylserine exposure. Science 344, 1164-1168. 10.1126/science.1252809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J., Denning D. P., Imanishi E., Horvitz H. R. and Nagata S. (2013). Xk-related protein 8 and CED-8 promote phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptotic cells. Science 341, 403-406. 10.1126/science.1236758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Halleck M. S., Schlegel R. A. and Williamson P. (1996). A subfamily of P-type ATPases with aminophospholipid transporting activity. Science 272, 1495-1497. 10.1126/science.272.5267.1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson O., Edgley M., Strasbourger P., Flibotte S., Ewing B., Adair R., Au V., Chaudhry I., Fernando L., Hutter H. et al. (2013). The million mutation project: a new approach to genetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 23, 1749-1762. 10.1101/gr.157651.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard A. L., Coleman J. A., Lemmin T., Mikkelsen S. A., Molday L. L., Vilsen B., Molday R. S., Dal Peraro M. and Andersen J. P. (2014). Critical roles of isoleucine-364 and adjacent residues in a hydrophobic gate control of phospholipid transport by the mammalian P4-ATPase ATP8A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E1334-E1343. 10.1073/pnas.1321165111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang J., Gengyo-Ando K., Gu L., Sun C. L., Yang C., Shi Y., Kobayashi T., Shi Y., Mitani S. et al. (2007). C. elegans mitochondrial factor WAH-1 promotes phosphatidylserine externalization in apoptotic cells through phospholipid scramblase SCRM-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 541-549. 10.1038/ncb1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.