Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the trajectories in the first year after individuals are admitted to long-term care nursing homes.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting:

US long-term care facilities

Participants:

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries newly admitted to long-term care nursing homes from 07/01/2012 to 12/31/2013 (N=535,202).

Measurements:

Demographic characteristics were from Medicare data. Individual trajectories were conducted using the Minimum Data Set for determining long-term care stays and community discharge, and Medicare Provider and Analysis Reviews claims data for determining hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility stays, inpatient rehabilitation, long-term acute hospital and psychiatric hospital stays.

Results:

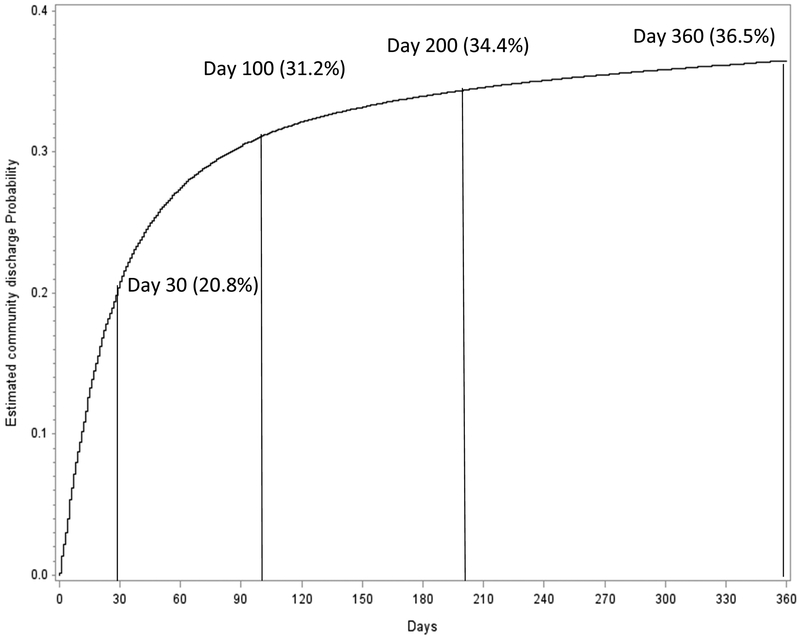

The median length of stay in a long-term care nursing home over the one-year following admission was 127 (interquartile range (IQR): 24, 356) days. The median length of stay in any institution was 158 (IQR: 38, 365). Residents experienced a mean of 2.1+/− 2.8 (standard deviation) transitions over the first year. The community discharge rate was 36.5% over the one year follow up, with 20.8% discharged within 30 days and 31.2% discharged within 100 days. The mortality rate over the first year of nursing home residence was 35.0%, with 16.3% deaths within 100 days. At 12 months post long-term care admission, 36.9% of the cohort were in long-term care, 23.4% were in community, 4.7% were in acute care hospitals or other institutions, and 35.0% had died.

Conclusion:

After a high initial community discharge rate, the majority of patients newly admitted to long term care experienced multiple transitions while remaining institutionalized until death or the end of one year follow up.

Keywords: Medicare, long-term care nursing home, residential history files, trajectory, community discharge

Introduction

Admission to a long-term care (LTC) nursing home represents a pivotal point in an individual’s life, with institutionalization signifying a loss of independence. A common trajectory ending in LTC nursing home admission is hospitalization1 followed by post-acute care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF).2 Individuals may transition from SNF to LTC services within the same facility, as nursing homes typically house both SNF “patients” and LTC “residents”. SNF services are short-term and recuperative, while receipt of LTC services signifies a more permanent placement.3

A number of investigators have examined outcomes after admission to LTC.1,4–6 Once in LTC, residents may be transferred to acute care hospitals or other institutional settings, such as SNFs, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, or psychiatric hospitals.5 Over a quarter of residents are hospitalized within the first year.1 Following hospitalization, residents often receive SNF services prior to returning to LTC.7,8 These transfers to other levels of care are typically short-term, and a majority of residents return to LTC.7 Approximating 20% of LTC residents are discharged to the community within a year of admission.3 Many will remain until death, and mortality rates of 12% to 34% have been reported over the first year of LTC nursing home residence.1,9,10

We took a different approach to describing outcomes among LTC residents. Rather than examine the rates of specific events, such as hospitalization, we attempted to describe the complete trajectory in the first year after individuals were admitted to LTC. To achieve this objective, we used a methodology developed by Intrator et al. to create residential history files for LTC nursing home residents.11 Using their algorithm, we linked Medicare claims data and nursing home Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessment records to determine residents’ setting for each day over their first year of residence.11 Specifically, we determined daily whether the individual was 1) in a LTC nursing home, 2) in an acute care hospital, 3) in another institutional setting, 4) discharged to the community, or 5) dead. Understanding what happens to newly-admitted LTC nursing home residents may provide insight into areas for care improvement. We describe the first year of LTC nursing home residence in a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries as a first step in answering these and other patient- and policy-relevant questions.

Methods

Data Sources

We used the 2012–2014 Medicare Beneficiary Summary files, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files, and Resident Assessment Instrument MDS 3.0 assessment files from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Beneficiary Summary files contain sociodemographic and monthly enrollment (i.e., Health Maintenance Organization [HMO], yes/no) information. The MedPAR file contains finalized claims for all Medicare Part A inpatient stays, including those in acute care hospitals, SNFs, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and psychiatric hospitals. The MDS files contain assessment records for SNF and LTC stays. Nursing homes typically house both patient populations. Medicare is the primary payer for SNF services and Medicaid is the primary payer for LTC services. Individuals are eligible for Medicare coverage if they are over the age of 65 years, disabled, or have end stage renal disease.12 Medicaid eligibility varies across states, but is typically available to individuals of all ages from low income households.12

Study Cohort

The cohort was individuals newly-admitted to a LTC nursing homes from 07/1/2012 through 12/31/2013. These individuals lived in the US, had not resided in LTC over the prior six months, were over the age of 65 years at LTC admission, had continuous Medicare Part A enrollment (no HMO) over the six months before and twelve months after LTC admission (N=535,202).

Resident Characteristics

We extracted residents’ age, gender, and ethnicity from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary files and used the Medicaid indicator in the year of admission to LTC as a proxy of low socioeconomic status. We used diagnoses in the MedPAR files from all hospital admissions in the prior year to identify dementia status (yes/no) (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes “331.0”, “331.11”, “331.19”, “331.7”, “290.0”, “290.10”, “290.11”, “290.12”, “290.13”, “290.20”, “290.21”, “290.3”, “290.40”, “290.41”, “290.42”, “290.43”, “294.0”, “294.10”, “294.11”, “294.8”, “797”) and Elixhauser comorbid conditions.13 We used the admission MDS assessment from the patient’s LTC stay to get information on marital status (married/unmarried), cognitive status (cognitively intact or mildly impaired/moderate or severely impaired)14 and physical functional status (six activities of daily living [ADL] items). Tetrachoric or polychoric correlations were performed to measure the correlations between the functional status items.15 The largest tetrachoric correlation between the functional items was 0.90. Because of this intercorrelation, we created a composite score (range 0–24) for functional status (higher scores indicating greater assistance with ADLs).

Residence in Long-term Care

We identified LTC stays using the method developed by Intrator, et al. 2011.11 This method uses claims data from the MedPAR files and assessment data from the MDS files to identify LTC stays. We identified SNF stays using claims in the MedPAR files. Any episodes in the MDS assessment files outside the dates of the SNF claims were considered LTC stays. We defined the start of an MDS episode as the entry date recorded in the assessment file and the end as the date of the last MDS assessment that listed the same entry date. We have validated this method of identifying LTC stays against Medicaid data, with 91% sensitivity and 87% positive predictive value.16,17.

We followed the newly-admitted LTC residents for 365 days or until death to create residential history files. We determined daily whether the individual was 1) in a LTC nursing home, 2) in an acute care hospital, 3) in another institutional setting, which we defined as SNF, inpatient rehabilitation facility, long-term acute care hospital, or psychiatric hospital, 4) discharged to the community, or 5) dead. We used MedPAR claims files to identify acute care hospital, SNF, inpatient rehabilitation facility, long-term acute care hospital, and psychiatric hospital stays. We defined community discharges as the discharge destination of the assessment was home or community.

Outcomes

We followed each resident to death or to one year after admission. We used the residential history files to determine the trajectory of each resident in the first year of LTC. We also determined length of stay in LTC over the one year following admission; days spent in any institutional setting; rates and timing of community discharge; and rates and timing of death.

Statistical analysis

We described the first four transitions (or until death or community discharge) for all residents. To construct these trajectories, we calculated the percentage of residents transitioning to 1) a LTC nursing home, 2) an acute care hospital, 3) another institutional setting, 4) the community, or 5) death.

We calculated descriptive statistics for resident characteristics stratified by cognitive status (intact or mildly impaired/moderately or severely impaired), Medicaid eligibility (yes/no) and functional status (ADL<=12/ADL>12) to describe the cohort. We calculated length of stay in LTC nursing homes and days spent in any institutional setting over the first year of LTC residence. We also calculated both of these measures as functions of total days alive over the one-year observation period. To examine survival and community discharge rates over the first year of LTC residence, we calculated Kaplan-Meier product limit estimators, censored at community discharge or death. We further used multilevel logistic models to assess state-level variation in rates of community discharge, adjusted for resident characteristics. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The final cohort included 535,202 residents who had previously lived in the community and who were newly-admitted to a LTC nursing home from 7/1/2012 to 6/30/2013. Resident characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 83.1 (SD: 8.5) years; 36.2% were male; 87.7% white. Table 1 also presents the number of emergency room visits, hospitalizations, percent who died, and the mean number of all transitions over the first year after admission to long term care, stratified by level of cognitive function, physical function and eligibility for Medicaid. In general the more impaired residents experienced fewer transitions, presumably because of the higher death rates among those patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort of new long-term care residents admitted from 07/01/2012 to 12/31/2013 (N=535,202).

| Cognitive Function Score | Medicaid | Physical Function Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact/mildly impaired | Moderate/Severe impaired | Yes | No | <=12 | >12 | ||

| All N (%) | 335,476 (62.68%) |

199,726 (37.32%) |

178,101 (33.28%) |

357,101 (66.72%) |

166,217 (31.06%) |

368,985 (68.94%) |

|

| Age | |||||||

| 65–70 | 51,192 | 47,728 (81.51%) |

9,464 (18.49%) |

21,378 (41.76%) |

29,814 (58.24%) |

19370 (37.84%) |

31,822 (62.16%) |

| 71–75 | 57,091 | 42,044 (73.64%) |

15,047 (26.36%) |

24,183 (42.36%) |

32,908 (57.64%) |

19,892 (34.84%) |

37,199 (65.16%) |

| 76–80 | 73,718 | 48,278 (65.49%) |

25,440 (34.51%) |

28,992 (39.33%) |

44,726 (60.67%) |

23,950 (32.49%) |

49,768 (67.51%) |

| 81–85 | 104,823 | 63,586 (60.66%) |

41,237 (39.34%) |

34,778 (33.18%) |

70,045 (66.82%) |

32,735 (31.23%) |

72,088 (68.77%) |

| 86–90 | 125,507 | 72,615 (57.86%) |

52,892 (42.14%) |

35,976 (28.66%) |

89,531 (71.34%) |

37,431 (29.82%) |

88,076 (70.18%) |

| 90+ | 122,871 | 67,225 (54.71%) |

55,646 (45.29%) |

32,794 (26.69%) |

90,077 (73.31%) |

32,839 (26.73%) |

90,032 (73.27%) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 193,816 | 123,261 (63.60%) |

70,555 (36.40%) |

54,842 (28.30%) |

138,974 (71.70%) |

60,687 (31.31%) |

133,129 (68.69%) |

| Female | 341,386 | 212,215 (62.16%) |

129,171 (37.84%) |

123,259 (36.11%) |

218,127 (63.89%) |

105,530 (30.91%) |

235,856 (69.09%) |

| Marital statusa | |||||||

| Married | 157,979 | 96,894 (61.33%) |

61,085 (38.67%) |

34,975 (22.14%) |

123,004 (77.86%) |

43,830 (27.74%) |

114,149 (72.26%) |

| Unmarried | 377,223 | 238,582 (63.25%) |

138,641 (36.75%) |

143,126 (37.94%) |

234,097 (62.06%) |

122,387 (32.44%) |

254,836 (67.56%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 469,208 | 298,953 (63.71%) |

170,255 (36.29%) |

137,652 (29.34%) |

331,559 (70.66%) |

149,022 (31.76%) |

320,186 (68.24%) |

| Black | 44,363 | 24,629 (55.52%) |

19,734 (44.48%) |

25,831 (58.23%) |

18,532 (41.77%) |

11,156 (25.15%) |

33,207 (74.85%) |

| Hispanic | 7,510 | 3,698 (49.24%) |

3,812 (50.76%) |

5,939 (79.08%) |

1,571 (20.92%) |

1,892 (25.19%) |

5,618 (74.81%) |

| Others | 14,121 | 8,196 (58.04%) |

5,925 (41.96%) |

8,679 (61.46%) |

5,442 (38.54%) |

4,147 (29.37%) |

9,974 (70.63%) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Count | |||||||

| 0–1 | 342,946 | 214,249 (62.47%) |

128,697 (37.53%) |

112,153 (32.70%) |

230,793 (67.30%) |

109,973 (32.07%) |

232,973 (67.93%) |

| 2 | 47,036 | 27,912 (59.34%) |

19,124 (40.66%) |

15,911 (33.83%) |

31,125 (66.17%) |

14,809 (31.48%) |

32,227 (68.52%) |

| 3 | 48,517 | 29,691 (61.20%) |

18,826 (38.80%) |

16,620 (34.26%) |

31,897 (65.74%) |

14,518 (29.92%) |

33,999 (70.08%) |

| 4 | 38,879 | 24,665 (63.44%) |

14,214 (36.56%) |

13,458 (34.62%) |

25,421 (65.38%) |

11,397 (29.31%) |

27,482 (76.69%) |

| 5+ | 57,824 | 38,959 (67.38%) |

18,865 (32.62%) |

19,959 (34.52%) |

37,865 (65.48%) |

15,520 (26.84%) |

42,304 (73.16%) |

| Number of emergency visitb | |||||||

| 0 | 344,201 | 210,423 (61.13%) |

133,778 (38.87%) |

108,575 (31.54%) |

235,626 (68.46%) |

110,153 (32.00%) |

234,048 (68.00%) |

| 1 | 118,261 | 74,786 (63.24%) |

43,475 (36.76%) |

40,831 (34.53%) |

77,430 (65.47%) |

35,093 (29.67%) |

83,168 (70.33%) |

| 2 | 43,208 | 29,042 (67.21%) |

14,166 (32.79%) |

16,209 (37.51%) |

26,999 (62.49%) |

12,677 (29.34%) |

30,531 (70.66%) |

| 3 | 16,873 | 11,939 (70.76%) |

4,934 (29.24%) |

6,797 (40.28%) |

10,076 (59.72%) |

4,820 (28.57%) |

12,053 (71.43%) |

| 4+ | 12,659 | 9,286 (73.35%) |

3,373 (26.65%) |

5,689 (44.94%) |

6,970 (55.06%) |

3,474 (27.44%) |

9,185 (72.56%) |

| Number of rehospitalizationb | |||||||

| 0 | 326,236 | 194,492 (59.62%) |

131,744 (40.38%) |

103,868 (31.84%) |

222,368 (68.16%) |

102,603 (31.45%) |

223,633 (68.55%) |

| 1 | 121,735 | 78,562 (64.54%) |

43,173 (35.46%) |

40,860 (33.56%) |

80,875 (66.44%) |

37,473 (30.78%) |

84,262 (69.22%) |

| 2 | 49,458 | 34,259 (69.27%) |

15,199 (30.73%) |

17,995 (36.38%) |

31,463 (63.62%) |

15,025 (30.38%) |

34,433 (69.62%) |

| 3 | 20,603 | 15,061 (73.10%) |

5,542 (26.90%) |

7,988 (38.77%) |

12,615 (61.23%) |

6,146 (29.83%) |

14,457 (70.17%) |

| 4+ | 17,170 | 13,102 (73.61%) |

4,068 (23.69%) |

7,390 (43.04%) |

9,780 (56.96%) |

4,970 (28.95%) |

12,200 (71.05%) |

| Dementia in the 12 months prior | |||||||

| Yes | 127,488 | 48,299 (37.89%) |

79,189 (62.11%) |

47,814 (37.50%) |

79,674 (62.50%) |

31,575 (24.77%) |

95,913 (75.23%) |

| No | 407,714 | 287,177 (70.44%) |

120,537 (29.56%) |

130,287 (31.96%) |

277,427 (68.04%) |

134,642 (33.02%) |

273,072 (66.98%) |

| Death within 12 months | |||||||

| Yes | 187,247 | 98,905 (52.82%) |

88,342 (47.18%) |

54,722 (29.22%) |

132,525 (70.78%) |

36,521 (19.50%) |

150,726 (80.50%) |

| No | 347,955 | 236,571 (67.99%) |

111,384 (32.01%) |

123,379 (35.46%) |

224,576 (64.54%) |

129,696 (37.27%) |

218,259 (62.73%) |

| Number of transitionsb | |||||||

| Mean (std) | 2.11 (2.8) | 2.22 (3.1) | 2.06 (2.7) | 2.22 (3.1) | 2.06 (2.7) | 2.27 (2.9) | 2.04 (2.8) |

| median (IQR) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

Other marital status (n=122) is not presented in the table.

The follow up time is 12 months after newly admitted to long term care or death.

The median length of stay in a LTC nursing home over the one year following admission was 127 (interquartile range (IQR): 24, 356) days. Of the total days alive in the one year following admission, 85.7% (median) (IQR: 14.5%, 100%) were spent in a LTC nursing home. The median length of stay in any institution, including LTC nursing homes, SNFs, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, and psychiatric hospitals, was 158 (IQR: 38, 365) days. Of the total days alive in the one year following LTC nursing home admission, 99.60% (median) (IQR: 26%, 100%) were spent in an institutional setting.

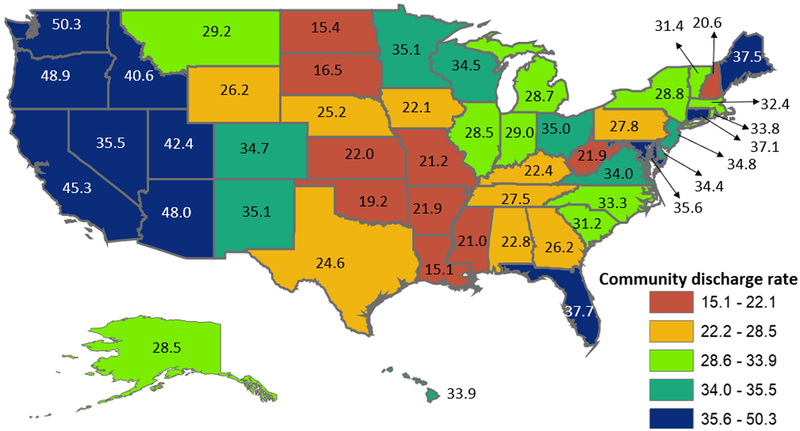

Among newly-admitted LTC nursing home residents, 33.4% were discharged to the community over the one-year follow up. Kaplan-Meier estimates indicate that 20.1% of residents were discharged to the community within 30 days of admission and 31.2% of were discharged to the community within 100 days (Figure 1). For those patients who were discharged to the community over the one year follow up, 37,252 (19.9%) died before the end of follow up. Rates of community discharge varied across states. Rates of community discharge by state, adjusted for resident characteristics in a multilevel model, are presented in Figure 2. Rates ranged from 15.1% in Louisiana to >50.0% in Washington. The appendix table presents the patient characteristics in the multilevel model predictions community discharge. Non-white ethnicity, female gender, younger agers being married, lack of Medicaid eligibility, few comorbidities, good cognitive function and fewer functional impairments all predicted community discharges.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Survival curve for community discharge within the first year of long-term care residence.

Figure 2.

Adjusted rates of community discharge by state. Rates are from a multi-level model adjusted for the resident characteristics listed in Table 1.

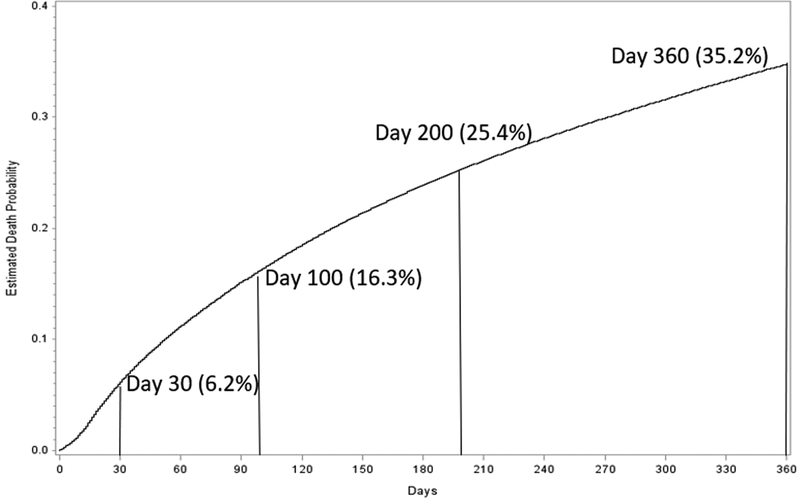

The mortality rate over the first year of nursing home residence was 35.0% (N=187,247). The deaths were evenly distributed throughout the year, with 15% within 100 days of admission and 25% within 200 days (appendix figure).

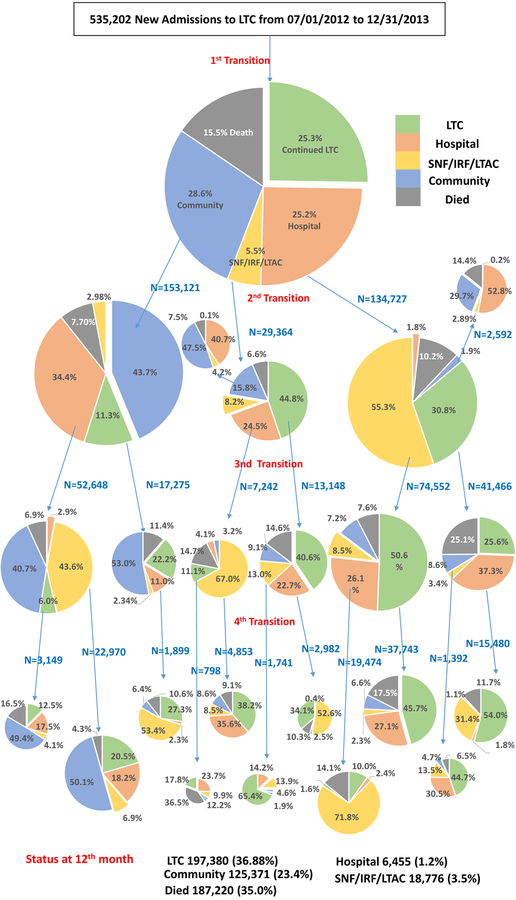

Figure 3 is an attempt to illustrate trajectories over the first year of LTC nursing home residence. In the cohort of 535,202 newly-admitted LTC nursing home residents, 28.6% (N=153,121) were discharged to the community prior to experiencing any other transitions; 15.5% (N=82,925) died prior to any transitions; and 25.3% (N=135,159) remained in LTC for the year without additional transition. The remaining residents (30.6%, N=163,997) experienced multiple transitions. A common trajectory observed (N=37,743) was LTC nursing home to acute care hospital (1st transition), acute care hospital to SNF/IRF/LTAC (2nd transition and SNF/IRF/LTAC to LTC nursing home (3rd transition).

Figure 3.

The first four transitions for long-term care (LTC) residents within 12 months after LTC admission.

Another common trajectory was for residents to cycle between LTC and the hospital over the first four transitions. Of residents whose first transition was to an acute care hospital, 30.8% (N=41,466) returned directly to LTC. Of these, 37.3% (N=15,480) were rehospitalized, with over half (54.0%, N=8,358) returning to LTC after hospitalization. Residents also cycled between hospitalization and SNF/IRF/LTAC. Of residents whose first two transitions were LTC to hospital and then hospital to SNF/IRF/LTAC (N=74,552), 26.1% were rehospitalized from the SNF/IRF/LTAC, with 71.8% (N=14,017) returning to SNF/IRF/LTAC care following hospitalization. Although less frequent, 5.5% of residents first transitioned from LTC directly to a SNF/IRF/LTAC. A majority of these individuals (44.8%, N=13,148) then returned to LTC; however, 24.5% (N=7,242) were rehospitalized from the SNF/IRF/LTAC. Of those rehospitalized, most (67.0%, N=4,853) received additional SNF/IRF/LTAC services prior to transitioning back to a LTC nursing home.

Some common trajectories were also observed among residents who discharged to the community at the first transition (N=153,121). Of those patients, 43.7% stayed in the community for the year without further institutionalization; 7.7% died at home without an additional transition; 11.3% (17,272) were readmitted to LTC, with 53.0% (9,163) of these returning to community; 34.4% (52,648) were admitted to acute hospitals, with 62.5% (32,919) returning to community after acute hospital and with or without SNF/IRF/LTAC stay. The one year death rate for patients who were discharged to the community at the first transition was 18.1% (27,751).

Regardless of their trajectory, at one year post-LTC nursing home admission, 36.9% of the cohort was in a LTC nursing home; 23.4% were in the community; 3.5% were in another institutional setting (SNF/IRF/LTAC); 1.2% were in an acute care hospital; and 35.0% had died.

Discussion

We created residential history files for a national cohort of new residents to examine their trajectories over this first year. The first year of LTC nursing home residence is a dynamic time. Although complex and variable, some common pathways emerged in our observational analysis. Notably, over one-third of newly admitted residents experienced multiple transitions, with at least one being a hospitalization.

The relatively high utilization of SNF services after hospitalization of long term care nursing home patients has been observed in prior studies among LTC nursing home residents with dementia,8,18 stroke,7 and hip fracture.7 Most LTC nursing homes also provide SNF services,19 and SNF services are regarded as more profitable.20 CMS has recognized the need for evidence to guide which patients would benefit from postacute care and how much care they should receive.21 Unnecessary utilization of these services leads to avoidable care transitions, which is important among vulnerable populations.14,22,23

Developing a better understanding of care trajectories following admission to long-term care nursing home residence is important for several reasons. Among the most significant is the expansion of episode based payment models. Important questions regarding when and where the episode begins and how long the episode lasts have not been solved.24,25 If episode based care becomes the standard payment model, there will be increased pressure for long-term care facilities to partner with hospitals and post-acute care providers. Information about patterns and trajectories of care will be helpful in identifying the appropriate partnerships. CMS currently measures the percentage of SNF patients who are discharged to the community as part of the Nursing home compare quality ratings. The trajectory of care results in our study should provide information related to application of similar quality metrics to long term care facilities.

Most LTC nursing home residents remained institutionalized until death or for at least a year; only 26.4% (N=141,300) were discharged to the community and remained alive one-year after LTC nursing home admission. Returning to the community is important from both individual and policy perspectives.26 At the individual level, avoiding long term institutionalization is highly prized.27–30 At the policy level, institutional LTC is costly, and Medicaid, the primary payer for LTC services and supports, is shifting funding from institutional to home- and community-based LTC services and supports.31

Medicaid policies vary at the state level, and we observed a variation in rates of community discharge across states. This variation in rates supports previous work indicating that some continued institutionalizations may be avoidable.32 In general, those states with higher rates of discharge to the community also tend to have lower admission rates to LTC nursing homes, as previously reported.16 However, the occurrence of a community discharge can have different meanings. For example, in additional analyses, we found that 6.0% (N=10,672) of the residents discharged to the community died within 30 days of discharge from the nursing home.

Limitations include the fact that we only assessed the first four transitions in the year. Also, because we restricted our cohort to those with continuous Medicare fee-for-service enrollment, our findings may not be generalizable to LTC nursing home residents covered by a Medicare HMO or another payer.

Conclusion

In summary, construction of residential history files is a feasible method for examining the trajectory of patients in LTC nursing homes.

Acknowledgments:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, Science Editor and Assistant Professor in the Sealy Center on Aging, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, for editorial assistance in manuscript preparation.

Founding/Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grants number R01AG33134, K05CA134923, R01HD069443, K12HD055929, P2CHD065702, and P30AG024832] and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [grant number R24HS22134]. The funding organizations had no role in the design of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- LTC

long term care

- SNF

skilled nursing facility

- CMS

the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- MDS

Minimum Data Set

- HMO

health maintenance organization

- MedPAR

Medicare Provider Analysis and Review

- IRF

inpatient rehabilitation facilities

- LTAC

long-term acute hospital

- IQR

interquartile range

Appendix Figure.

Kaplan-Meier Survival curve of mortality in the year after admission to a long term care nursing home of Medicare recipients who had previously lived in the community.

Appendix Table.

Percent of patients discharge community within 12 months follow up, with odds ratios from a multilevel analysis, including patients and states.

| Patient characteristic | N | Percentage of community discharge (%) | ORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 535,202 | 33.36 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 469,208 | 33.40 | 1.00 |

| Black | 44,363 | 32.37 | 1.35 (1.25, 1.36) |

| Hispanic | 7,510 | 30.68 | 1.53 (1.45, 1.62) |

| Others | 14,121 | 36.48 | 1.30 (1.25,1.36) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 193,816 | 34.89 | 1.00 |

| Female | 341,386 | 32.49 | 1.24 (1.22,1.25) |

| Age in years | |||

| 66–70 | 51,192 | 50.66 | 1.00 |

| 71–75 | 57,091 | 42.70 | 0.80 (0.77, 0.81) |

| 76–80 | 73,718 | 36.14 | 0.63 (0.62, 0.65) |

| 81–85 | 104,823 | 32.34 | 0.53 (0.52, 0.54) |

| 86–90 | 125,507 | 29.52 | 0.46 (0.45, 0.47) |

| 91+ | 122,871 | 24.94 | 0.37 (0.36, 0.38) |

| Marital statusb | |||

| Married | 157,979 | 40.65 | 1.00 |

| Unmarried | 377,223 | 30.31 | 0.70 (0.69, 0.71) |

| Medicaid eligibility | |||

| Yes | 178,101 | 21.97 | 1.00 |

| No | 357,101 | 39.04 | 2.91 (2.87, 2.96) |

| Number of Comorbidities | |||

| 0,1 | 326,236 | 34.43 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 121,735 | 31.57 | 0.91 (0.89, 0.93) |

| 3 | 49,458 | 31.28 | 0.89 (0.87, 0.91) |

| 4 | 20,603 | 31.20 | 0.86 (0.84, 0.88) |

| >=5 | 17,170 | 31.67 | 0.83 (0.81, 0.84) |

| Cognitive Function Score | |||

| Intact/mildly impaired | 335,476 | 42.83 | 1.00 |

| Moderately/severely impaired | 199,726 | 17.45 | 0.32 (0.31, 0.33) |

| Physical Function Score | |||

| 0–12 | 166,217 | 42.32 | 1.00 |

| 13–24 | 368,985 | 29.33 | 0.59 (0.58, 0.60) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Odds ratios are from a multilevel logistic regression model adjusted for all characteristics presented in the table, and state of residence.

Other marital status (n=122) is not presented in the table, but was included in the model.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial or personal conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Tanuseputro P, Chalifoux M, Bennett C, et al. Hospitalization and Mortality Rates in Long-Term Care Facilities: Does For-Profit Status Matter? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015;16:874–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin JS, Howrey B, Zhang DD, Kuo YF. Risk of continued institutionalization after hospitalization in older adults. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2011;66:1321–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gassoumis ZD, Fike KT, Rahman AN, et al. Who transitions to the community from nursing homes? Comparing patterns and predictors for short-stay and long-stay residents. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2013;32:75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai S, Rahman M, Intrator O. Obesity and pressure ulcers among nursing home residents. Med Care. 2013;51:478–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Malley AJ, Caudry DJ, Grabowski DC. Predictors of nursing home residents’ time to hospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:82–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAndrew RM, Grabowski DC, Dangi A, Young GJ. Prevalence and patterns of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in the US long-term care setting. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28:104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoverman C, Shugarman LR, Saliba D, Buntin MB. Use of postacute care by nursing home residents hospitalized for stroke or hip fracture: how prevalent and to what end? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1490–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Givens JL, Mitchell SL, Kuo S, et al. Skilled nursing facility admissions of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1645–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flacker JM, Kiely DK. Mortality-related factors and 1-year survival in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holup AA, Gassoumis ZD, Wilber KH, Hyer K. Community Discharge of Nursing Home Residents: The Role of Facility Characteristics. Health Serv Res. 2016;51:645–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, et al. The residential history file: studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories(*). Health Serv Res. 2011;46:120–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of the Actuary CfMMS. Brief Summaries of Medicare & Medicaid. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/Downloads/MedicareMedicaidSummaries2016.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 13.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Hyer K, et al. Effect of forced transitions on the most functionally impaired nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1895–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drasgow F. Polychoric and polyserial correlations. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. 1988.

- 16.Middleton A, Zhou J, Ottenbacher KJ, Goodwin JS. Hospital Variation in Rates of New Institutionalizations Within 6 Months of Discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1206–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin JS, Li S, Zhou J, et al. Comparison of methods to identify long term care nursing home residence with administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldfeld KS, Stevenson DG, Hamel MB, Mitchell SL. Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health and Human Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015 Edition. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/nursinghomedatacompendium_508-2015.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- 20.Grabowski DC. Medicare and Medicaid: conflicting incentives for long-term care. Milbank Q. 2007;85:579–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. June 2016; Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/data-book/june-2016-data-book-health-care-spending-and-the-medicare-program.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 7/20/2016.

- 22.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doupe M, Brownell M, St John P, et al. Nursing home adverse events: further insight into highest risk periods. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2011;12:467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sood N, Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, et al. Medicare’s bundled payment pilot for acute and postacute care: analysis and recommendations on where to begin. Health Affairs. 2011;30:1708–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechanic RE. Opportunities and challenges for episode-based payment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:777–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.RTI International. Measure Specifications for Measures Adopted in the FY 2017 SNF QRP Final Rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/Measure-Specifications-for-FY17-SNF-QRP-Final-Rule.pdf. Accessed 8/23/2016.

- 27.Tse MM. Nursing home placement: perspectives of community-dwelling older persons. Journal of clinical nursing. 2007;16:911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krothe JS. Giving Voice to Elderly People: Community-Based Long-Term Care. Public Health Nursing. 1997;14:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenberg NE, Coward RT. Attitudes about entering a nursing home: Comparisons of older rural and urban African-American women. Journal of Aging Studies. 1997;11:27–47. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prince D, Butler D. Clarity final report: aging in place in America. Nashville, TN: Prince Market Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eiken S, Sredl K, Burwell B, Saucier P. Medicaid Expenditure for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2014: Managed LTSS Reached 15 Percent of LTSS Spending. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/downloads/ltss-expenditures-2014.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- 32.Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, Feng Z, et al. Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1762–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]