Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Family physician (FP) is one of the best strategies to reform health system and promote population health. Due to the different context, culture, and population, implementing this reform within cities would be more challenging than in rural areas. This study aimed to assess the challenges and strengths of Urban FP Program in Fars Province of Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

It was a qualitative study using framework analysis for collecting and interpreting data. The participants included health policy-makers, top managers, and involved health staff selected through purposive and snowball sampling. Participating in the program or working as a physician in urban areas were among inclusion criteria. Three focus groups with experts as well as the content analysis of national documents were also performed. The research tool was a semi-structured interview guide. Interviews and focus groups were recorded and transcribed word by word. The framework of triangle for data analysis and the content was analyzed using MAXQDA 2010 software.

RESULTS:

The participants’ mean age was 44.9 ± 6.4 years, with a mean work experience of 13.2 ± 7.4 years. The transcripts revealed six themes and 17 subthemes. The emerging themes included three challenges and three solutions as following: social problems, financial problems, and structural problems as well as resistance reduction, executive meetings, and surveillance.

CONCLUSION:

Resolving staff shortage, decreasing the public resistance, and eliminating unnecessary referrals were among the strategies used by Fars, during FP implementation. To be successful in implementing this program, the required perquisites such as infrastructures and culture growth must be undertaken. The current study suggests the establishment of the electronic health record to improve the pace and quality of service provision as well as reducing violations.

Keywords: Family physician, Iran, qualitative research, Urban Health Services

Introduction

The history of family physician (FP) returns to 1950 in the UK. It then was extended to Europe, Canada, and other countries with significant improvements in health care.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests FP as the base of quality improvement, cost-effectiveness, and equity for health-care systems.[2]

FPs provide coordinated care to patients and their families. They actively engage in disability prevention. Besides, as gatekeepers, FPs make decisions about the appropriate use of health resources and assist patients in identifying their health needs to choose efficient services. FP acts as a bridge between population and the health-care system to provide equitable and efficient health care.[3,4] This care leads to early and prompt diagnosis and treatment.[5]

It is believed that the implementation of Urban FP Program (UFPP), changes the payment system, diminishes payments at the first level of service delivery, and establishes a referral system in which one can utilize specialized services and the insurance company pays most of the costs. It finally decreases drug costs with better insurance coverage, and consequently, direct costs of the households would be reduced.[5] According to the WHO, the less referral is, the better decision-making will be, which would result in the improvement of health outcomes as well as increase in human and economic efficiency.[6]

The rural parts of Iran were underdeveloped and suffered from poor health until the Islamic revolution occurred in 1979.[7] Later by introducing Primary Health Care (PHC), the health network system was developed and lots of Iran's health challenges solved for many years.[8,9] Gradually, health system failed to respond to the emerging needs of the population because of high burden of noncommunicable diseases, public expectation to access qualified physicians, and fast-growing technologies.[10,11] Therefore, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) initiated a series of health sector reforms, including the pilot phase of FP program as a basic health plan in rural areas based on the fourth 5-year national development plan in 2005.[12,13,14] These reforms in rural areas and small cities with populations under 20,000 individuals made very sharp improvements, especially in major health indicators, such as maternal mortality, life expectancy, and the control of infectious diseases.[1] Following the successful experience of FP program in rural regions, MOHME decided to expand this program to urban areas. Hence, FP program started to be implemented as a pilot in cities with <50,000 people in three provinces (Khuzestan, ChaharMahal-Bakhtiari, and Sistan va Baluchistan) in 2010.[15] For every population about 2000–4000 people, a team of FPs was assigned consisting of general patients (GPs), midwives, providers of laboratory services, and pharmaceutical services.[16] However, due to public greater access to private providers in cities, the PHC network remained unsuccessful.[12]

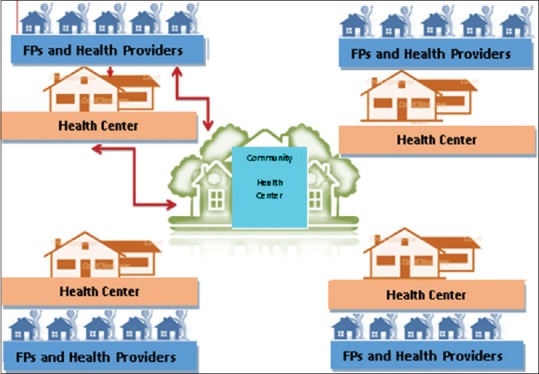

Urban settings in Iran has some institutional characteristics that may hinder the implementation of FP policy. A passive and fragmented PHC network, powerful private sector with a huge conflict of interest with FPs, public's freedom of choice to use health services, and multidimensional and various cultural norms compared with rural regions are among these characteristics. Besides, specialists in the private sector as the most powerful stakeholders of the cities do not advocate preventive services provided by FPs in Iran.[7] Hence, a pilot program of FP, namely the FP and Referral System Instruction, version 2, was launched and two provinces of Iran were selected to implement it in their cities. Fars and Mazandaran were the pilot provinces and the program was started in Fars, Fasa in 2013. The structure of UFFP in Iran is presented in Figure 1. Considering the role of FP in health promotion and regarding its establishment problems in urban areas of Iran, detecting FP implementation challenges as well as the managers’ and policy-makers’ experiences, who are the key stakeholders and deal with all aspect of the program, seems essential.

Figure 1.

The structure of Urban Family Physician Program in Iran, Fars

Several national surveys have attempted to identify the policy-making of FP in Iran, and even considered the challenges of its establishment in urban areas.[13,17,18] To describe these concerns more accurately, some studies have used qualitative methods. Common themes among these studies include imperfect referral system, lack of proper feedback to FPs from specialist, huge duties, uncertain financial resources, and policy-making challenges, but most have focused on specific towns or expert groups. Since there is a gap in the literature on this issue, especially within developing countries like Iran, further research in this area seems required. The current study aimed to assess the challenges related to the national UFPP of Iran 4 years after its implementation in 2017.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

This study was partial of a PhD thesis supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences. It was approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR. IUMS. Rec1395/9221557205). Informed consents were obtained from the participants. The participants were informed about the study objectives and procedures before each interview and were told that their participation was voluntary.

Study design

This study was conducted at two levels: national and regional. A qualitative design with framework analysis was used in order to collect and interpret data.

Fars is a Southern province of Iran with a population of approximately 4,851,000 people, 1100 FP, and 774 health center, the majority of which is private (70% vs. 30%). Fars has 29 cities including Shiraz, the capital of Fars.

The inclusion criteria of the current study consisted of:

Participating in the UFPP (from design to implementation) for at least 3 years or working in UFPP as a physician for at least 2 years of clinical experience in urban areas and having tendency to participate in the study for experts, and

Being familiar with UFFP and visiting him/her having a FP in Fars for at least 3 years and willingness to participate for patients.

The purposeful and snowball sampling was used to identify research participants at both national and regional levels. The participants were national and regional policy-makers, managers, physicians, health professionals, patients, and members of the public who actively or passively affected the process of decision-making, management, and implementation of UFPP.

The sample study was included national and regional policy-makers, managers, doctors, patients, health professionals, as well as FP officers who influenced the process of decision-making, formulating, and implementing of FP program. The researchers interviewed health policy-makers, top managers, and health staff who were involved in the FP program and were well experienced and informed about the challenges of this program.

At the beginning, three in-depth interviews were conducted to have an understanding of the subject and developing appropriate questions. Overall, 24 interviews: 14 national and 10 local interviews (6 females and 18 males) were conducted to reach data saturation. The interviewer started with general questions and moved forward more detailed inquiries depending on the participants’ responses. The major interview questions were as follows: “How was the UFPP implemented?” What are your experiences of UFFP?” “What are the opportunities/strengths of UFPP?”, “What are the challenges/problems of UFPP?” and “Would you have any recommendations? If so, what would they be?” At the end of the interviews, the researcher thanked the participants for devoting time and asked them whether they would like to add anything. The interviews continued until there was no new information.

Three focus groups were also conducted with experts, plus a content analysis of national documents. Focus groups were started with a clear description of the research goal and the members responded to the questions based on brainstorm technique.

Our research tool was a semi-structured interview guide. Interviews and focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were studied several times to make a comprehensive perception, then they were read line by line, the coding was applied, and after that, the themes and subthemes were defined. To increase validity, the interviews were read frequently and the colleagues’ comments were used. Besides, to enhance reliability, the external monitoring was applied, for this, a part of data was reposed to a researcher out of this work to see whether he has a similar perception of data or not. To analyze data, the framework of triangle and MAXQDA 2010 software was applied.

Results

Our sample included four FPs and 20 health policy-makers/top managers as well as patients. The participants’ mean age was 44.9 ± 6.4 years, with a mean work experience of 13.2 ± 7.4 years as a health manager and 2 ± 5 years as FP. The mean population size covered by each FP was 2500 individuals. The participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Coding and the analysis of data revealed six themes and got categorized into two main categories: the challenges (problems) and strengths (solutions) of the UFPP implementation in Iran. These two categories are presented in Table 2 and explained in the following section. The transcripts were devoted to the categories of challenges/problems and strengths/solutions extracted from transcripts including six themes as well as 17 subthemes. These subthemes pointed to different aspects of challenges and strengths in the implementation of UFPP of Iran.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristics | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Value*(%) | Range | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 18 (75) | |

| Female | 6 (25) | |

| Age (year) | 44.9±6.4 | 32-70 |

| Education | ||

| Physician | 15 (62.5) | |

| Nonphysician | 9 (37.5) | |

| Job | ||

| Top manager/policy-maker | 13 (54.2) | |

| Physician/officer | 7 (29.2) | |

| Public representatives | 4 (16.6) | |

| Work experience (year) | 13.2±7.4 | 3-30 |

*Data are presented in mean±SD or n (%). SD=Standard deviation

Table 2.

The extracted themes and subthemes from the participants’ transcripts

| Categories | Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| A. Challenges/problems | 1. Social problems | Emerging issues |

| Public dissatisfaction | ||

| 2. Financial problems | Money transfer between budget items | |

| Payment with delay | ||

| Multiple insurance funds | ||

| 3. Structural problems | Lack of electronic records | |

| Law deviation | ||

| FP problems | ||

| Discrimination | ||

| Resistance against implementation | ||

| B. Opportunities/solutions | 4. Responsiveness | Mass media |

| FPs’ notice | ||

| Financial incentives | ||

| 5. Executive meetings | Solving insufficient staff eliminating unnecessary refers | |

| 6. Surveillance | Sib electronically system | |

| Judging committee |

FPs=Family physicians

Category A: Challenges/problems

The first category included the challenges of UFPP. Its themes were social problems, financial problems, and structural problems.

Theme 1: Social problems

Social problems was the first extracted theme. Its subthemes were as follows:

Emerging issues: some participants pointed to some unexpected issues that emerged out of this plan. For example one of the participants said “in order to cover all population, we announced public registration for free national insurance to include all uninsured people, however, the rate of registration came double times more than the estimation of the actual number of people without any insurance; it happened because some employees that were previously paying their parents insurance premium, started to register their parents in this free insurance plan, and because we had not predicted this issue in our national insurance plan, it imposed an extra financial burden to us while we did not have its required financial resources”

Public dissatisfaction: Population growth, increasing public expectation, unfamiliarity with UFFP, cultural resistance, etc., were among the problems that most participants expressed in this regard. Dissatisfaction was mentioned specially in regard of referral system as one of the participants argued: “The patients just came to FP to receive a confirmed referral form to visit a specialist at a very reasonable price.” In addition, a participant complained that: “Whenever I visit my FP, he does not give me a referral form to visit a specialist, so I tend to change my FP.” While another participant expressed that: ”Our FP does not examine us, rather than any checkup, she asks whether we tend to visit a specialist and after that she quickly fills out a referral form based on our wish.”

Theme 2: Financial problems

All participants mentioned financial problems as a big challenge of UFPP. The subthemes of this problem were as the following:

Money transfer between budget lines: some participants believed that the financial barrier to FP stems from budget line transfers. In this regard, a participant stated: ”For the year 2012, the Ministry of Health set a significant budget for UFPP, however, it was not devoted to UFPP completely.” Another participant added that: ”Insurance funds protested to this issue that the money of FP Budget line in 2012 was not received by UFPP and instead it was spent on something rather than UFPP”

Payment with delay: The participants acknowledged that payments were not on-time in this program. A participant said: ”the payments delay may be one to 2 months.” another participant argued: ”when the FP receives money with delay, he will ignore respect and dignity to his patients.” An involved manager in UFPP added: ”Now we are in November and not only October payments are not transferred to physicians or even it is not on the progress, but also the payments for July and in some cases for August have just settled recently”

Multiple insurance funds: Most participants pointed to multiple insurance funds as a big dilemma in Iran's health specially UFPP. For example, a participant expressed that: ”due to the multiple insurance funds, each fund collects money separately, and as a result, the payments are different across the funds.”

Theme 3: Structural problems

These problems were due to poor infrastructure. Its subthemes are described below:

Lack of health electronic records: Some participants felt that the cause of many problems in UFPP implementation is missing the electronic records. A participant said that: ”due to fragmented information databases if a patient out of FP service hours need visiting a doctor and goes to the hospital, the physician working in Emergency Department has no access to the patient's record.” Another participant added that ”an important helping tool in UFPP is the implementation of electronic records which detects and eliminates frauds and violations”

Law deviation: Disobedience, violation of the law, and ignoring the rules were mentioned by some participants as a challenge in UFPP. A participant stated that ”some physicians have collusion with pharmacy to write specific drugs, either near to expire or out of pharmacopeia.” Another participant added that:”FPs who cover a population <500 people must be excluded from the program, however, they remain in the program and work part-time as a FP in the evenings while they are working as an officer in the mornings, so illegally they do not pay practice costs but can act as a GP”

FP's team problems: The problems of referral as well as FP ignorance were among the problems related to FP team acknowledged by participants. The following statements illustrate this issue: ”people were satisfied with free of charge visits for UFPP but if the physician did not refer them to the specialist, the patients reacted and wanted to sue it to a powerful body like parliament representatives,” “The FPs could refer between 50%and 70%t of patients and this raised insurance costs, because the insurance had to reimburse both FP and the specialist because of their corporation in UFPP and referral system.” “FP working hours in the morning is till 12 pm, it is too short that we have no time to see our FP after doing house works, so can only we visit him in the evenings,” “FPs do not respect the patients and devote few time to them or in some cases they visit several patients together”

Discrimination: Some participants pointed to discrimination and injustice which exists whether across general and specialties or within FP and health staff. For instance, a participant reported that: ”all insured persons pay a specific premium but those who have a clinic FP, have limited access because clinic FPs are working part-time.”

Resistance against implementation: A majority of participants pointed to the public as well as physician resistance to UFPP, especially at the start of the program. A participant said that: ”this program was not accepted by public culture, so the rate of objection was huge.” Another participant expressed that: ”the specialists were among the most powerful opposing group against the implementation of UFFP.”

Category B: Strengths/solutions

Theme 4: Resistance reduction

The executive participants mostly expressed that the resistance was too high at the beginning of the program implementation but by the following solutions the resistance turned into advocacy. The major subthemes in this regard include the following:

Mass media: many participants acknowledged that mass media had a great impact on public awareness and acceptance. A participant expressed that: ”at the beginning of the program, the advertisement for FP was abundant across the city, lots of banners, billboards, and stands were announcing the public registration as well as its benefits to population.” Another participant added that: ”there were many informing TV or Radio programs about FP which hosted Fars University of Medical Sciences’ chairman or his Deputies”

FPs’ notice: The participants pointed to notices as a way to deal with physician resistance. A participant said that: ”We have a website to announce physicians the news, as well, we send SMS to FPs when the news is updated. Also, there is an online payment system by which the physicians see whether their money is paid or not”

Financial incentives: A frequent expressed factor by participants was financial incentives which contributed to resistance reduction. A participant mentioned that: ”the financial incentive was so strong, that currently, the largest proponent groups are GPs.” Another participant added that: ”… although the payments was not on-time, however, it was so encouraging that soon attracted GPs to this program.” Another participant said: ”Previously, we had to pay a little money but now it is free of charge to see a doctor, so whenever we feel sick, we can see our FP without being worry to pay its fee.”

Theme 5: Executive meetings

The executive participants talked about weekly meetings in which the problems were discussed and proper some solution were made to them. The subthemes of these meetings are as follows:

Solving insufficient staff: some participants pointed to staff insufficiency. The following statements are presenting this issue:

”In version 02, the midwives are suggested to be in FP team, but because the insufficient number of midwives, we corresponded with MOHME to replace midwives with general or family hygiene officers.”

”According to FP Instruction, every 2500 population must be covered by a FP, but due to physician shortage, this program was implemented with a FP per 3000 population in Shiraz and 3500 population in other cities”

Eliminating unnecessary refers: one problem mostly expressed by participants as the pitfall of UFFP was huge unnecessary referrals. To solve it, some actions were made as a participant acknowledged: ”the people were going to FP, only to get a referral form, so it was approved if a FP's referral exceeds 20% of his/her visits, his/her income will be deducted.”

Theme 6: Surveillance

The evaluation and monitoring of UFPP was of importance. This theme has two subthemes as:

Sib electronic system: This was an electronic software used by FP team, recording all patients’ data as well as the clinical activities of the FPs for the enrolled population covered by their team. A participant said: ”the FPs are monitored by Sib System. All his/her recorded activities are visible to us. For example, we know what drugs have been prescribed or even how much data has entered to the software.” Another participant said: ”a file is devoted to all of us including our disease history, laboratory results, and physical status, besides our FP's assistant fills out our records with patient and accuracy”

Judging committee: The executive participants reported that there were so many complaints at the beginning of the UFPP implementation that a judging committee started up to solve these disagreements. A participant acknowledged: ”Here, they formed a weekly-held judging committee to consider the complaints… its members for judging on complaints included insurance representatives and FP authorities.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the challenges and strengths of UFPP in Fars Province of Iran. FPs, patients, policy-makers, managers, and those affected on or by UFPP were interviewed and the results were categorized under challenges/problems and strengths/solutions.

Despite fundamental diversity in health financing, organization, and service delivery among different countries, they experience the same challenges in the field of FP.[5]

The findings of the current study showed that social problems are expressed as an important challenge and public dissatisfaction was an important subtheme of it. People have to use the referral system to visit a specialist at a reasonable price. In other words, one should refer to a specialist if needed, and in case he/she is referred by his/her FP, most of his/her cost is paid by the insurance, but if referral system is not followed, insurance financial resources cannot be enjoyed.[1] Nasrollahpour Shirvani et al. emphasized that a correct referral system would meet about 80%–90% of public health needs based on Stephen study.[19,20] Therefore, many of diseases are diagnosed by FP and would be curable at the first level of the system, thus the FPs do not refer the GPs to a specialist. Hence, some of these patients had complaint that why their FP is not referring them to a specialist. Therefore, some physicians refer their patients as they requested their FP to do so. This is in line with the findings of Forrest et al.[21] Besides, as Nasrollahpour Shirvani et al. reported, the perquisites of referral system such as information, education, and intervention are not provided.[22] Nasiripour et al. also reported a deficiency in the referral system of FP in Kashan.[23]

According to this study, the economic problems also were reported by participants as a UFPP issue. Similarly, other researchers in Iran reported this issue in their study.[24,25] One major failure in this regard was payment with delay. Previous studies also reported this issue as one of the important weaknesses of FP in Maragheh and Mazandaran.[20,26] In this regard, Amiresmaili et al. reported that two-third of the physicians intended to leave the program due to irregular payments.[8] Another subtheme of the mentioned theme was multiple insurance funds. UFFP in Iran is supported financially by three insurance funds; each with their own policy, different pay time, and particular purchasing. Before UFPP implementation, the insurance companies must get merged to a health insurance according to the 5-year development plan,[1] however, in Iran, they are not integrated. In line with these results, Dehnavieh et al. also reported the diversity of insurances and lack insurance unity as an important challenge.[24]

According to the current study, structural problems were another challenge. A core subtheme of this problem that was frequently expressed by participants was lack of electronic health record. This record contains the information about patient's health care during his/her lifetime. FP at the first level of referral system is responsible for diagnosis, treat, and refer to higher levels. Hafezi et al. expressed that electronic health record is crucial for implementing FP.[27] Nasiripour et al. also confirmed that electronic records would act as a stimulator for specialists to face their referral patients.[23] In Iran, the infrastructure of electronic health record does not exist.[26] Hence, the physicians have to fill the patient health record in Sib system which is not extended to all centers. Negligence in filling the patient's records interfere with the proper completion of patient health records which is the requirements of FP program. FP team problem was another subtheme of the above-mentioned challenge. The participants complained about the referral problems such as unnecessary referrals and physician negligence like irrespective manners. Similarly, the findings of Golalizadeh et al. was in line with our study.[13] Another issue regarding FP was reported as the tendency of people to visit the specialists. Resistance against implementation was the last subtheme of this challenge.

The participants also talked about some solutions by which they handled UFPP in Fars. One of these solutions was applied to reduce resistance. Mass media was a subtheme of this category. The participant talked about TV, radio, and other mass media by which the UFPP was introduced to public. Previous studies also expressed that TV was the most important source of information.[28,29]

Executive meetings was another category as a solution to UFPP discussed by some participants. Within these meeting, the problems were discussed and proper solution presented and approved by its members. Solving the insufficient staff by replacing hygiene officers instead of midwives was an example of these solutions. Besides, unnecessary referrals which were expressed by participants was another problem. In the same way, Mohaghegh et al. reported that some FPs feel that they have low control on referral decisions due to the social pressure.[10] In the current study, the participants argued how this issue was also solved through the instructions approved by these executive meetings which limited the referrals up to 20% of total FP visits.

Surveillance was the last theme of our findings. Safizadehe Chamokhtari et al. in their study reported that the weakness of monitoring and evaluation was among the most frequent challenges complained by their interviewees.[30] In the current study, the participants explained that through Sib software, UFPP is monitored and judging committees help to solve the disagreements and consequently prevent the future problems.

Conclusion

Implementing UFPP, due to its different population, diverse service providers and services, and higher public expectations, is much more difficult compared with rural FP program. Hence, assessing the implementation of this program in different time zones is of importance. Although the implementation of UFPP in Iran had so many pitfalls, it had some achievements also.[2,31,32] Resolving staff shortage, decreasing the public resistance, and eliminating unnecessary referrals were among the strategies used by Shiraz, the capital city of Fars Province, during UFPP implementation. Due to the difference between the urban and rural setting, the required perquisites such as infrastructures and culture growth must be undertaken. First of all, to solve the social problems, community awareness must be increased to promote public culture for using UFFP correctly, besides public cooperation must be enhanced to decrease unnecessary FP visit, reduce costs and consequently promote FP efficiency and public health. Also considering the important role of nurses in FP program, insufficient number of nurses would have a bad effect on service quality.[33] Hence, essential strategies should be adopted to attract more nurses to this program. The current study also suggests the establishment of the electronic health record to improve the pace and quality of service provision as well as reducing violations. Another recommendation would be merging the insurance funds to make a solid and harmonized financial flow. Furthermore, implementing a strong monitoring system and improving the referral system is suggested.

This study faced some limitations. First, due to using qualitative method, the extracted themes and subthemes are better to be examined through quantitative method for more accurate results. Second, the study was conducted on policy-makers/managers/physicians/patients and in a single geographical area, that is, Shiraz, Iran. Therefore, findings should be cautiously generalized to other settings, populations, and areas. Further studies in other regions and other stakeholders may provide more reliable results concerning the challenges and strengths of FP.

In general, this study gives policy-makers a better understanding to face the challenges of UFFP. In addition, our findings may be used to create a framework for expanding this program to other cities and hopefully leading the improvement of FP program in the world.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study is a partial of a PhD thesis approved and supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: IUMS/SHMIS_ 1395/9221557205).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was part of a PhD thesis approved by the ethics committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC1395.9221557205). All policy-makers, managers, FPs, and patients who agreed to participate in the current study as well as the anonymous reviewers who helped with their suggestions are appreciated. The authors would also like to thank the research deputy of Iran University of Medical Sciences for supporting this study (grant No: IUMS/SHMIS. REC1395.9221557205).

References

- 1.Majdzadeh R. Family physician implementation and preventive medicine; opportunities and challenges. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:665–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khayyati F, Motlagh ME, Kabir M, Kazemeini H, Gharibi F, Jafari N, et al. The role of family physician in case finding, referral, and insurance coverage in the rural areas. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40:136–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatam N, Joulaei H, Kazemifar Y, Askarian M. Cost efficiency of the family physician plan in Fars Province, Southern Iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2012;37:253–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalhor R, Azmal M, Kiaei MZ, Eslamian M, Tabatabaee SS, Jafari M, et al. Situational analysis of human resources in family physician program: Survey from Iran. Mater Sociomed. 2014;26:195–7. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.26.195-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabet Sarvestani R, Najafi Kalyani M, Alizadeh F, Askari A, Ronaghy H, Bahramali E, et al. Challenges of family physician program in urban areas: A Qualitative research. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20:446–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, Tandon A, Cortez R. Going Universal: How 24 Developing Countries are Implementing Universal Health Coverage from the Bottom Up. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 5 Going Universal: How 24 Developing Countries are Implementing Universal Health Coverage from the Bottom Up Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khayatzadeh-Mahani A, Takian A. Family physician program in Iran: Considerations for adapting the policy in urban settings. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17:776–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amiresmaili M, Khosravi S, Feyzabadi VY. Factors affecting leave out of general practitioners from rural family physician program: A Case of Kerman, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:1314–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vosoogh Moghaddam A, Damari B, Alikhani S, Salarianzedeh M, Rostamigooran N, Delavari A, et al. Health in the 5th 5-years development plan of Iran: Main challenges, general policies and strategies. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:42–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohaghegh B, Seyedin H, Rashidian A, Ravaghi H, Khalesi N, Kazemeini H, et al. Psychological factors explaining the referral behavior of Iranian family physicians. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e13395. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.13395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manca DP, Varnhagen S, Brett-MacLean P, Allan GM, Szafran O, Ausford A, et al. Rewards and challenges of family practice: Web-based survey using the Delphi method. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:278–86, 277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takian A, Doshmangir L, Rashidian A. Implementing family physician programme in rural Iran: Exploring the role of an existing primary health care network. Fam Pract. 2013;30:551–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golalizadeh E, Moosazadeh M, Amiresmaili M, Ahangar N. Challenges in second level of referral system in family physician plan: A qualitative research. Journal of Medical Council of I.R.I. 2012;29(4):309–321. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honarvar B, Lankarani KB, Rostami S, Honarvar F, Akbarzadeh A, Odoomi N, et al. Knowledge and practice of people toward their rights in urban family physician program: A Population-based study in shiraz, Southern Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:46. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.158172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dehnavieh R, Kalantari AR, Jafari Sirizi M. Urban family physician plan in Iran: Challenges of implementation in Kerman. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohammadi M. Patient satisfaction with urban and rural insurance and family physician program in Iran. J Fam Reprod Health. 2011;5:11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damari B, Vosough Moghaddam A, Rostami Gooran N, Kabir MJ. Evaluation of the urban family physician and referral system program in Fars and Mazandran Provinces: History, achievements, challenges and solutions. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2016;14:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takian A, Rashidian A, Doshmangir L. The experience of purchaser-provider split in the implementation of family physician and rural health insurance in Iran: An institutional approach. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:1261–71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephen W. Primary medical care and the future of the medical profession. World Health Forum. 1981;2(3):316. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasrollahpour Shirvani, Raeisee, P, Motlagh, ME, Kabir, MJ Evaluation of the performance of referral system in family physician program in Iran University of Medical Sciences: 2009.”. Hakim Research Journal. 2010;13(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forrest CB, Nutting PA, Starfield B, von Schrader S. Family physicians’ referral decisions: Results from the ASPN referral study. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasrollahpour Shirvani D, Ashrafian Amiri H, Motlagh M, Kabir M, Maleki MR, Shabestani Monfared A, et al. Evaluation of the function of referral system in family physician program in northern provinces of Iran: 2008. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2010;11:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasiripour A, Motaghi M, Navvabi N. The performance of referral system from the perspective of family physicians of Kashan university of medical sciences: 2007-2012. J Health Promot Manag. 2014;3:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dehnavieh R, Kalantari AR, Jafari Sirizi M. Urban family physician plan in Iran: Challenges of implementation in Kerman. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:1219–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lankarani KB, Alavian SM, Haghdoost AA. Family physicians in Iran: Success despite challenges. Lancet. 2010;376:1540–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janati A, Maleki MR, Gholizadeh M, Narimani M, Vakili S. Assessing the strengths and weaknesses of family physician program. Knowledge & Health. 2010;4(4):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hafezi Z, Asqari R, Momayezi M. Monitoring performance of family physicians in Yazd. Toloo-e-Behdasht. 2009;8:16–25. Number1-2 (26) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tavoosi A, Zaferani A, Enzevaei A, Tajik P, Ahmadinezhad Z. Knowledge and attitude towards HIV/AIDS among Iranian students. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majidpour A, Habibzadeh S, Amani F, Hemmati F. The role of media in knowledge and attitude of students about AIDS. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2006;6:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safizadehe Chamokhtari K, Abedi G, Marvi A. Analysis of the patient referral system in urban family physician program, from stakeholdersperspective using swot approach: A qualitative study. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2018;28:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vosoogh Moghaddam A, Damari B. The Effects of Family Medicine on Promoting Service Quality and Controlling Health Costs. The nd National and thest International Conference on the Appropriate Experiences and Functions of Primary Health Care System. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barati O, Maleki MR, Gohari M, Kabir M, Amiresmaili M, Abdi Z, et al. The impact of family physician program on health indicators in Iran (2003-2007) Payesh. 2012;11(3):361–63. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarea K, Negarandeh R, Dehghan-Nayeri N, Rezaei-Adaryani M. Nursing staff shortages and job satisfaction in Iran: Issues and challenges. Nurs Health Sci. 2009;11:326–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]