Summary

Carney complex (CNC) is a rare multiple neoplasia syndrome characterized by spotty pigmentation of the skin and mucosa in association with various non-endocrine and endocrine tumors, including primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD). A 20-year-old woman was referred for suspected Cushing syndrome. She had signs of cortisol excess as well as skin lentigines on physical examination. Biochemical investigation was suggestive of corticotropin (ACTH)-independent Cushing syndrome. Unenhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen did not reveal an obvious adrenal mass. She subsequently underwent bilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy, and histopathology was consistent with PPNAD. Genetic testing revealed a novel frameshift pathogenic variant c.488delC/p.Thr163MetfsX2 (ClinVar Variation ID: 424516) in the PRKAR1A gene, consistent with clinical suspicion for CNC. Evaluation for other clinical features of the complex was unrevealing. We present a case of PPNAD-associated Cushing syndrome leading to the diagnosis of CNC due to a novel PRKAR1A pathogenic variant.

Learning points:

PPNAD should be considered in the differential for ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome, especially when adrenal imaging appears normal.

The diagnosis of PPNAD should prompt screening for CNC.

CNC is a rare multiple neoplasia syndrome caused by inactivating pathogenic variants in the PRKAR1A gene.

Timely diagnosis of CNC and careful surveillance can help prevent potentially fatal complications of the disease.

Background

Carney complex (CNC) is a rare multiple neoplasia syndrome characterized by spotty pigmentation of the skin and mucosa, myxomas and endocrine tumors. It was first described by Dr J Aidan Carney at Mayo Clinic in 1985 and is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, with approximately 30% of cases occurring due to de novo genetic event (1, 2). More than 70% of affected individuals have identifiable pathogenic variants in the PRKAR1A gene, which encodes the regulatory type 1 alpha subunit of the enzyme protein kinase A (3).

The manifestations of CNC are wide ranging and include spotty skin pigmentation (pigmented lentigines and blue nevi on the face – including the eyelids, vermillion borders of the lips, the conjunctivae, the sclera – and the labia and scrotum); myxomas (cardiac atrium, cutaneous, and mammary); primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD); testicular large-cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumors; growth-hormone secreting pituitary adenomas; osteochondromyxomas and psammomatous melanotic schwannomas. PPNAD typically presents with corticotropin (ACTH)-independent cortisol excess (1). We describe a patient with Cushing syndrome that proved to be caused by PPNAD in the setting of CNC due to a novel PRKAR1A pathogenic variant. We also highlight several important aspects of diagnosis and management in this rare disorder.

Case presentation

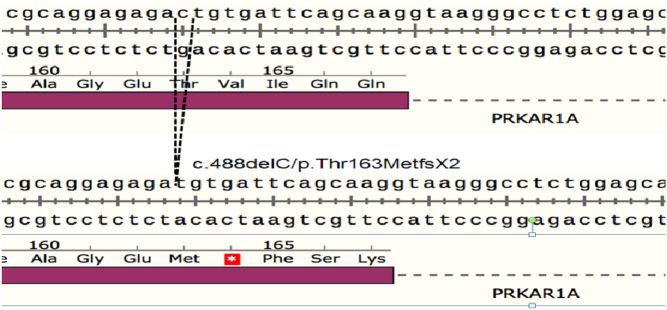

A 20-year-old woman with bilateral avascular necrosis of the femoral heads was referred by her orthopedic surgeon for suspected Cushing syndrome. She reported a 34 kg weight gain over 1 year, red abdominal striae, rounding of the face and worsening anxiety. She denied exogenous corticosteroid use, with the exception of intra-articular hip injections. She was normotensive, and her body mass index was 34 kg/m2. Physical exam showed facial plethora, moon facies, dorsocervical fat pad, truncal obesity, red abdominal striae and mild hirsutism. She was noted to have multiple brown macules, including lentigines over the lips and a café-au-lait spot on the neck (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Skin examination was notable for lentigines on the lips (A) and a café-au-lait spot on the neck (B).

Investigation

On biochemical workup, midnight salivary cortisol (60 ng/dL; reference range (RR): <100 ng/dL) and 24-h urinary free cortisol (22 µg; RR: 3.5–45 µg) were within normal limits. However, she had non-suppressible serum cortisol of 9.5 µg/dL (262 nmol/L) and 13.0 µg/dL (359 nmol/L) following 1 mg and 8 mg dexamethasone suppression tests, respectively. Serum ACTH concentration was undetectable at <5.0 pg/mL, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate was low (37 µg/dL; RR: 44–332 µg/dL) – findings consistent with ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome (Table 1). Unenhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen did not reveal an obvious adrenal mass and was read as normal (Fig. 2). Based on the biochemical and imaging findings, PPNAD was suspected.

Table 1.

Biochemical investigation.

| Parameters | Result | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Midnight salivary cortisol (ng/dL) | 60 | <100 |

| 24-h urinary free cortisol (µg) | 22 | 3.5–45 |

| 08:00 AM serum cortisol (µg/dL) | 8 | 7–25 |

| Serum cortisol (µg/dL) following administration of | ||

| 1 mg dexamethasone | 9.5 | <1.8 |

| 8 mg dexamethasone | 13.0 | <1.8 |

| Corticotropin (pg/mL) | <5.0 | 10–60 |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (µg/dL) | 37 | 44–332 |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 (ng/mL) | 147 | 85–370 |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 11.2 | 4.79–23.3 |

Figure 2.

Bilateral adrenal glands (arrows) appeared normal on computed tomography without significant hyperplasia or obvious adrenal nodules.

Treatment

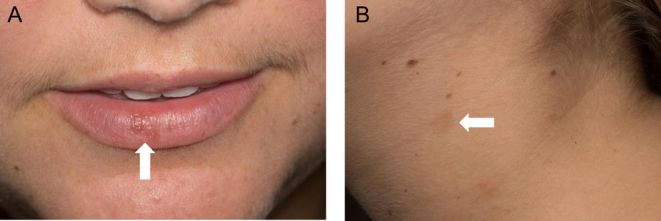

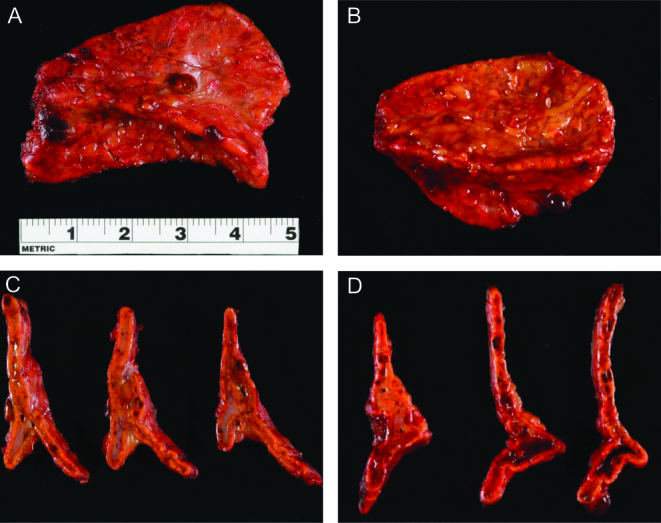

Bilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy was performed. Gross specimens showed adrenal glands of normal weight and size. Multiple tan-brown nodules were noted on cross sectioning (Fig. 3). Histology was consistent with PPNAD (Fig. 4). She was initiated on hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone replacement therapy and counseled on adrenal insufficiency management.

Figure 3.

Gross examination showed left (A) – 5.1 g, 4.7 × 3.2 × 1.2 cm – and right (B) – 5.0 g, 4.5 × 3.0 × 1.5 cm – adrenal glands within normal weight and size. Multiple tan-brown nodules were seen on the capsule and within the cortex on cross-sectioning (C and D).

Figure 4.

Adrenal histology with hematoxylin and eosin stain: objective magnification ×4 (A) and ×10 (B). Well-circumcised nodules are seen containing brown pigment and cells with round-to-oval nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Outcome and follow-up

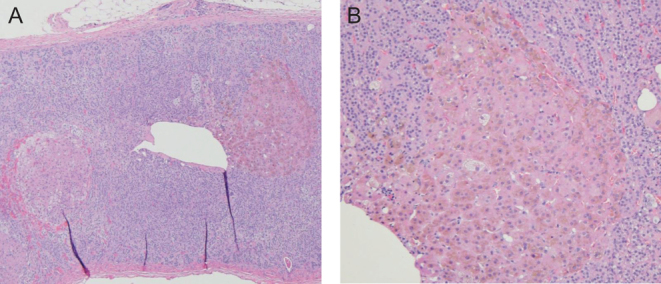

Medical genetics was consulted for further evaluation. A detailed family history was negative for CNC features. Genetic testing showed a novel frameshift pathogenic variant c.488delC/p.Thr163MetfsX2 in the PRKAR1A gene, resulting in a premature stop codon (Fig. 5). The variant was predicted to cause loss of protein function through either protein truncation or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, consistent with the clinical suspicion for CNC. Evaluation for other components of CNC did not detect myxomas, a growth-hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma, osteochondromyxoma or psammomatous melanotic schwannoma.

Figure 5.

Gene sequencing revealed a novel pathogenic variation in the PRKAR1A gene. Deletion of the cytosine base (c.488delC) changes codon Threonine 163 to a Methionine residue and creates a premature Stop codon at position 2 of the new reading frame (p.THr163MetfsX2).

Signs of cortisol excess improved following bilateral adrenalectomy. At 1-year follow-up, she was clinically well and had lost approximately 23 kg of body weight. Repeat echocardiogram to screen for cardiac myxoma was negative. Femoral head necrotic lesions resolved without the need for orthopedic intervention.

Discussion

In this case report, we describe a young woman with ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome who was ultimately diagnosed with PPNAD and CNC. She was found to have a novel pathogenic variant in the PRKAR1A gene predicted to cause loss of normal protein function.

PPNAD is the most common endocrine manifestation in CNC, affecting up to 60% of individuals with a gender predilection (70% women) (3, 4). It has a characteristic appearance on histology with multiple small (<1 cm) black-brown nodules scattered throughout the cortex (2), but can be challenging to diagnose otherwise. In this case, there were several suggestive features on clinical presentation and workup. The patient was a young woman in her 20s, which is consistent with the peak age of diagnosis for PPNAD and CNC (3, 4). She had signs of cortisol excess on physical exam, but 24-h urinary free cortisol was within the reference range. The normal urinary free cortisol measurement is not unusual, as cortisol production in PPNAD can be cyclic, and even seasonal (1). Serum cortisol was non-suppressed following 1 mg dexamethasone administration and rose further with 8 mg dexamethasone. This paradoxical rise in cortisol with dexamethasone administration has previously been described in patients with PPNAD (5), and an increase in urinary glucocorticoid excretion with dexamethasone is among the diagnostic criteria for CNC (6).

Imaging studies can also be used to distinguish PPNAD from more common causes of ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome. In this case, computed tomography scan of the abdomen did not show adrenal atrophy to suggest exogenous glucocorticoid administration, adrenal mass to suggest adenoma or carcinoma, or significant nodular hyperplasia to suggest bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. In fact, the adrenal glands were read as normal on the radiology report. Imaging findings suggestive of PPNAD, including irregular contour and well-delineated hypodense lesions, may be missed due to the small size of pigmented nodules. Computed tomography slice thickness should be 3 mm or less for optimal evaluation (4, 7). The treatment of choice for PPNAD is bilateral adrenalectomy.

PPNAD can occur as part of CNC, a rare multiple neoplasia syndrome characterized by spotty skin pigmentation, myxomas and endocrine tumors. The diagnosis of CNC can be made based on major clinical manifestations, laboratory findings and/or genetic testing (Table 2). In this case, the patient had histologic confirmation of PPNAD on bilateral adrenalectomy and an inactivating PRKAR1A alteration on gene sequencing. Pathogenic variants in the PRKAR1A gene are seen in 70% of patients with CNC, and up to 80% of patients with CNC and Cushing syndrome (3, 8). More than 125 PRKAR1A pathogenic variants have been described thus far (https://prkar1a.nichd.nih.gov/hmdb/prkar1a.html), with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Our patient was found to have a novel frameshift pathogenic variant (c.488delC/p.Thr163MetfsX2), resulting in a premature stop codon. She had PPNAD and a few scattered lentigines, but no additional CNC characteristics.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for Carney complex (CNC) (1, 6). A patient should meet (1) two major criteria or (2) one major and one supplemental criterion to establish the diagnosis of CNC

| Clinical manifestations | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Major criteria | |

| Spotty skin pigmentation with typical distribution | |

| Lentigines | 70–80 |

| Café-au-lait macules | Rare |

| Cutaneous and mucosal myxoma | 30–55 |

| Cardiac myxoma | 20–40 |

| Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) and/or paradoxical increase in urinary glucocorticoid excretion in response to dexamethasone administration during Liddle’s test | 25–60 |

| Acromegaly due to growth hormone-producing pituitary adenoma | 10–12 |

| Large-cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumor | 41–70 |

| Thyroid carcinoma (papillary or follicular type) | Up to 10 |

| Psammomatous melanotic schwannomas | Up to 10 |

| Blue nevus, epithelioid blue nevus | 40 |

| Breast ductal adenoma (multiple) | 14–25 |

| Osteochondromyxoma | Rare |

| Supplemental criteria | |

| Affected first-degree relative | |

| Inactivating mutation of the PRKAR1A gene | |

| Activating pathogenic variants of PRKACA and PRKACB |

Several case series have also described patients with isolated PPNAD and underlying PRKAR1A mutations (9, 10). These examples suggest CNC should be considered among all patients with PPNAD, even if clinical history and exam are negative for other features of the complex. Timely diagnosis and regular surveillance for CNC manifestations may help prevent complications of the disease, particularly those due to tumors in the heart. Cardiac myxomas affect 20–40% of patients with CNC and can lead to embolic strokes, heart failure and arrhythmias. Recommendations for CNC screening tests include echocardiogram (annually or biannually depending on history of cardiac myxoma), skin evaluation, thyroid ultrasound, pituitary magnetic resonance imaging, testicular/ovarian ultrasound and serum measurement of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor 1 and prolactin (1).

Conclusion

We present a case of Cushing syndrome leading to the diagnosis of CNC due to a novel predicted inactivating pathogenic variant in the PRKAR1A gene. PPNAD, in association with CNC, should be considered in the differential for ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome, especially when adrenal imaging appears normal. Timely diagnosis of CNC and careful surveillance can help prevent potentially fatal complications of the disease.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Patient consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for the submitted article and accompanying images.

Author contribution statement

C Zhang conducted the literature review and manuscript writing. P Pichurin, A Bobr, M Lyden and I Bancos were involved in the care of the patient and assisted with manuscript preparation. W Young Jr provided expert input for the case and manuscript.

References

- 1.Correa R, Salpea P, Stratakis CA. Carney complex: an update. European Journal of Endocrinology 2015. 173 M85–M97. ( 10.1530/EJE-15-0209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carney JA, Gordon H, Carpenter PC, Shenoy BV, Go VL. The complex of myxomas, spotty pigmentation, and endocrine overactivity. Medicine 1985. 64 270–283. ( 10.1097/00005792-198507000-00007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertherat J, Horvath A, Groussin L, Grabar S, Boikos S, Cazabat L, Libe R, Rene-Corail F, Stergiopoulos S, Bourdeau I, et al Mutations in regulatory subunit type 1A of cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase (PRKAR1a): phenotype analysis on 353 patients and 80 different genotypes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009. 94 2085–2091. ( 10.1210/jc.2008-2333) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcoutsakis NA, Tatsi C, Patronas NJ, Lee CC, Prassopoulos PK, Stratakis CA. The complex of myxomas, spotty skin pigmentation and endocrine overactivity (Carney complex): imaging findings with clinical and pathological correlation. Insights into Imaging 2013. 4 119–133. ( 10.1007/s13244-012-0208-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stratakis CA, Sarlis N, Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Doppman JL, Nieman LK, Chrousos GP, Papanicolaou DA. Paradoxical response to dexamethasone in the diagnosis of primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 1999. 131 585–591. ( 10.7326/0003-4819-131-8-199910190-00006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stratakis CA, Kirschner LS, Carney JA. Clinical and molecular features of the Carney complex: diagnostic criteria and recommendations for patient evaluation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001. 86 4041–4046. ( 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7903) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doppman JL, Travis WD, Nieman LK, Miller DL, Chrousos GP, Gomez MT, Cutler GB, Jr, Loriaux DL, Norton JA. Cushing syndrome due to primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease: findings at CT and MR imaging. Radiology 1989. 172 415–420. ( 10.1148/radiology.172.2.2748822) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cazabat L, Ragazzon B, Groussin L, Bertherat J. PRKAR1A mutations in primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease. Pituitary 2006. 9 211–219. ( 10.1007/s11102-006-0266-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyssikatos C, Pavithran PV, Tirosh A, Faucz FR, Vasukutty JR, Belyavskaya E, Ahamed A, Raygada M, Stratakis CA. Newly diagnosed Carney complex in 3 young adults with primary adrenal Cushing syndrome – a case series and review of the literature. AACE Clinical Case Reports 2017. 3 e326–e330. ( 10.4158/EP161541.CR) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groussin L, Horvath A, Jullian E, Boikos S, Rene-Corail F, Lefebvre H, Cephise-Velayoudom FL, Vantyghem MC, Chanson P, Conte-Devolx B, et al A PRKAR1A mutation associated with primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease in 12 kindreds. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006. 91 1943–1949. ( 10.1210/jc.2005-2708) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a