Abstract

Haemaphysalis longicornis, an invasive Ixodid tick, was recently reported in the eastern United States. The emergence of these ticks represents a potential threat for livestock, wildlife, and human health. We describe the distribution, host-seeking phenology, and host and habitat associations of these ticks on Staten Island, New York, a borough of New York City.

Keywords: Haemaphysalis longicornis, Asian longhorned tick, ticks, distribution, host-seeking phenology, habitat associations, bacteria, vector-borne infections, zoonoses, Staten Island, New York, United States

The invasive Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, is rapidly becoming an agricultural and epidemiologic concern in the United States. Native to eastern Asia, this tick is a major pest of domestic livestock throughout its invasive range in Australia, New Zealand, and surrounding islands (1,2) and also parasitizes wildlife and humans (2,3). The Asian longhorned tick is a vector of various pathogens infectious to humans (3,4), including severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China, which can be transmitted transstadially and transovarially to other ticks and mice (5). It is unknown whether these ticks also transmit pathogens endemic to the United States, or could contribute to the galactose-α-1,3-galactose meat allergy currently associated with Amblyomma and Ixodes tick species (6).

Although H. longicornis ticks have been detected by the US Department of Agriculture on quarantined horses and livestock for several years, it only recently became a health concern when high densities were found feeding on a nonimported domestic sheep in New Jersey (7) and in field collections in New York, New York (W. Bajwa, pers. comm.). These ticks have also been detected in eastern and southern US states including New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and Arkansas (3).

Rapid emergence of H. longicornis ticks might be facilitated by their ability to reproduce parthenogenetically (3,4,7,8) and tolerate a wide range of environmental temperatures (−2°C to 40°C), although they are most successful in moist, warm-temperate conditions (9). H. longicornis ticks are a 3-host tick, similar to other Ixodid ticks (9), and have variable phenology depending on latitude (9,10). The phenology of H. longicornis ticks in the United States has not been characterized.

H. longicornis ticks might feed on a wide range of mammalian and avian hosts, which enables rapid geographic expansion (2,9). In New Zealand, H. longicornis ticks prefer habitat with Dallas grass (Paspalum dilatatum) and rushes (Juncus spp.) (9), plants abundant throughout the Midwestern and southern United States that could provide suitable habitat. In New Jersey, H. longicornis ticks were found in areas with unmowed grass (7), suggesting that these ticks might occupy wider habitat ranges than Amblyomma and Ixodes ticks.

We aimed to assess the ability of H. longicornis ticks to establish in the United States, their potential to acquire endemic human pathogens, and possible exposure risk to humans. We investigated the questing phenology and host and habitat associations in public parks and peridomestic environments of an emerging population of H. longicornis ticks on Staten Island, New York, during 2017–2018.

The Study

All protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University (protocol AAAR3750) and an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocols AC-AAAX4454 and AC-AAAS6470). Sampling efforts on public lands began in June 2017 when 13 forest sites were surveyed for questing ticks. During June 30–August 10, 2017, we removed avian-derived ticks from mist-netted birds at Freshkills Park on Staten Island. During June 3–August 24, 2018, we surveyed 24 forest and grassland sites for questing ticks and 8 forested grid sites for questing and mammal-derived ticks. Questing ticks were obtained by dragging a 1-m2 corduroy cloth over the leaf litter, which was checked every 10 m or 20 m and all attached ticks were removed. White-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) were trapped biweekly for 2 consecutive nights in Sherman live traps (https://www.shermantraps.com) separated by 10 m in 10 × 5 trap grids.

During August 5– 21, 2018, we anesthetized 16 male white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and groomed them for ticks from 4 locations: College of Staten Island, Clay Pit Ponds, Mount Loretto State Forest and Freshkills Park. Mount Loretto State Forest, and Freshkills Park are dominated by grassland and wetland ecosystems, and Clay Pit Ponds is characterized by dense forest. College of Staten Island has manicured landscaping with grass and forest (separated by fencing) along the perimeter. While deer were anesthetized, we checked antlers, ears/head, front legs, hind legs, and body for ticks. Each animal was screened for 15 min to minimize time spent under anesthesia. Ticks were removed with forceps and stored in 100% ethanol for later identification.

During June 6–July 13, 2018, tick sampling was conducted on residential properties, which were selected by using a random cluster sampling strategy within areas previously identified as high risk given their proximity to parks (within 100 m). Houses were visited once, and questing ticks were collected along property edges by using the same method as in public parks.

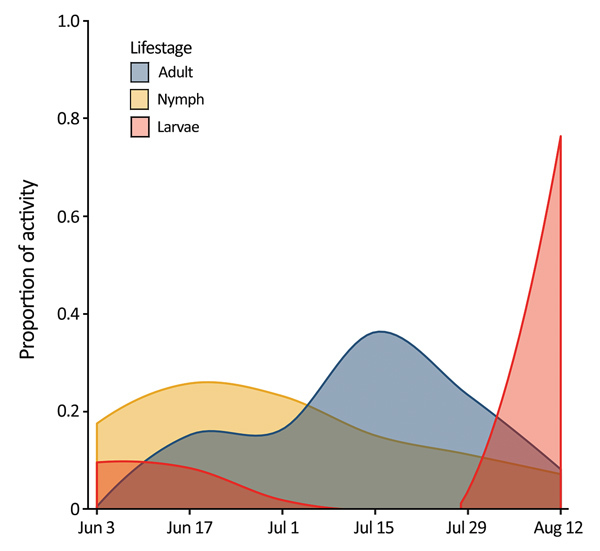

We found questing H. longicornis ticks at 7 of 13 parks surveyed in 2017 and 16 of 32 parks surveyed in 2018 (Table 1). Adult ticks were most active in late July and nymphs were active from mid-June to mid-July, similar to findings in South Korea (11). Larvae showed highest proportional activity in late August (Figure 1). We identified ticks primarily by morphology; a representative sample of specimens from deer and drag collections (n = 63) were confirmed as H. longicornis ticks by DNA barcoding using the cytochrome c oxidase I locus (12).

Table 1. Sites surveyed for Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks, Staten Island, New York, USA, 2017 and 2018*.

| Year and location |

Surveyed |

Habitat |

Density/1,000 m2* |

Adult |

Nymph |

Larvae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | ||||||

| Bloomingdale Park | Questing | Forest | 3.1 (2) | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Blue Heron Park | Questing | Forest | 0.9 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Clay Pit Ponds State Park Preserve | Questing | Forest | 61.5 (2) | 5 | 89 | 0 |

| Clove Lakes Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conference House Park | Questing | Forest | 7.4 (2) | 7 | 78 | 0 |

| Freshkills Park | Questing; host | Grassland | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Great Kills Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High Rock Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latourette Park | Questing | Forest | 1.3 (3) | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Lemon Creek Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Silver Lake Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.3 (2) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Willowbrook Park | Questing | Forest | 0.8 (2) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wolfe’s Pond Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | ||||||

| Arden Woods Park | Questing; host | Forest | 2.7 (6) | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Bloomingdale Park | Questing | Forest | 5.9 (3) | 0 | 13 | 0 |

| Blueberry Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blue Heron Park | Questing; host | Forest | 0.3 (6) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bunker Pond Park | Questing | Forest | 1.4 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Clay Pit Ponds State Park Preserve | Questing; host | Forest | 146.2 (3) | 26 | 280 | 70 |

| Clove Lakes Park | Questing; host | Forest | 0.0 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| College of Staten Island | Questing; host | Grassland | 676.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 169 |

| Conference House Park | Questing; host | Forest | 509.7 (6) | 128 | 1,058 | 343 |

| Deere Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Freshkills Park | Questing; host | Grassland | 11.0 (1) | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| Goodhue Park | Questing; host | Forest | 0.3 (6) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Great Kills Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High Rock Park | Questing | Forest | 3.3 (1) | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Hybrid Oak Woods Park | Questing | Forest | 13.6 (3) | 6 | 18 | 1 |

| Ingram Woods Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jones Woods Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| King Fisher Park | Questing; host | Forest | 0.0 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latourette Park | Questing; host | Forest | 5.3 (6) | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| Lemon Creek Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Midland Field Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Miller Field Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mount Loretto State Forest | Questing; host | Grassland | 675.0 (1) | 2 | 1 | 78 |

| Ocean Breeze Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reed's Basket Willow Swamp Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seidenberg Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Silver Lake Park | Questing | Grassland | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wegener Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Westwood Park | Questing | Forest | 0.7 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Willowbrook Park | Questing; host | Forest | 1.0 (6) | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Wolfe's Pond Park | Questing | Forest | 0.0 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Woodhull Park | Questing | Forest | 1.7 (1) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

*Adult, nymph, and larval counts include questing ticks only. Values in parentheses indicate no. visits per site.

Figure 1.

Seasonal activity of Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks (adults, nymphs, and larvae), Staten Island, New York, USA. Questing ticks were pooled by 2-week collection sessions during June 3–August 23, 2018.

In 2017, we processed 39 birds: 11 American robins (Turdus migratoriu), 1 common yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas), 20 gray catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis), 2 house wrens (Troglodytes aedon), 1 indigo bunting (Passerina cyanea), 3 northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis), and 1 American yellow warbler (Setophaga petechia). We found no H. longicornis ticks of any life stage. We found no H. longicornis ticks on 87 uniquely tagged P. leucopus mice (190 individual captures), 2 eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus), 14 northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda), and 1 brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). All life stages were recovered from deer at all 4 locations, and larvae were the most prevalent stage collected (Table 2). These findings indicate that immature stages of these ticks might feed exclusively on white-tailed deer or unsampled medium-sized animals. The high proportion of larvae on deer was probably caused by sampling during peak larval activity.

Table 2. Number of Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks removed from 16 deer on Staten Island, New York, USA.

| Location* | Adult | Nymph | Larvae | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City University of New York College of Staten Island, n = 10 | 7 | 1 | 193 | 201 |

| Clay Pit Ponds State Park Reserve, n = 3 | 56 | 63 | 217 | 336 |

| Mount Loretto State Forest, n = 2 | 90 | 4 | 63 | 157 |

| Freshkills Park, n = 1 | 15 | 6 | 140 | 161 |

| Total, n = 16 | 168 | 74 | 613 | 855 |

*Values indicate no. deer screened at each location.

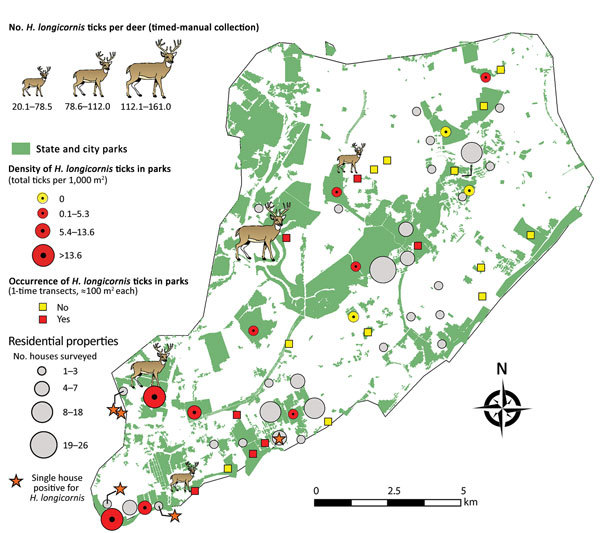

We surveyed 135 residential properties (average size 1,455 m2) (total visited = 505), of which 80% were located adjacent to parks in south and central Staten Island (Figure 2). Ticks were present at 34.1% of inspected properties. H. longicornis nymphs (n = 16) were found at 5 properties (in tall grass and shaded lawns), all located in the southern section of the island; no other life stages were found.

Figure 2.

Sampling site locations and number of Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks collected on deer, in parks (grids and transects), and during household visits on Staten Island, New York, USA.

Conclusions

The ability of H. longicornis ticks to feed on a wide range of domestic and wildlife hosts, reproduce asexually, and survive various environmental conditions likely contributed to their establishment throughout the eastern United States. All 3 life stages were found feeding on white-tailed deer in August, together with 2 other established tick species (A. americanum and I. scapularis). Pathogen transmission by co-feeding has been documented in field and laboratory studies (13,14) and could be a potential mechanism for H. longicornis ticks acquiring pathogens when feeding alongside infected A. americanum or I. scapularis ticks.

We found no H. longicornis ticks on P. leucopus mice or avian hosts even in sites with high densities of questing ticks, limiting the potential for this tick to acquire human pathogens. In New Zealand, immature life stages were commonly found on hares and goats, and adults were frequently found on larger mammals; the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) was touted as a major disseminator (9,15). These findings indicate the need for extensive sampling of other mammalian hosts. Finding H. longicornis ticks on residential properties is a human health concern because its potential as a vector of human pathogens in the United States is unknown. The combination of suitable habitat types, a plethora of host species, and high humidity make most regions of the United States suitable for H. longicornis tick establishment and proliferation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and Staten Island summer field assistants and household survey assistants for participating in this study.

This study was supported by Cooperative Agreement No. U01CK000509-01 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Biography

Dr. Tufts is a geneticist and disease ecologist at Columbia University, New York, NY. Her research interests include infectious diseases, tickborne pathogens, ecology, and evolutionary genetics.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Tufts DM, VanAcker MC, Fernandez MP, DeNicola A, Egizi A, Diuk-Wasser MA. Distribution, host-seeking phenology, and host and habitat associations of Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks, Staten Island, New York, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Apr [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2504.181541

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Heath AC, Palma RL, Cane RP, Hardwick S. Checklist of New Zealand ticks (Acari: Ixodidae, Argasidae). Zootaxa. 2011;2995:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoogstraal H, Roberts FH, Kohls GM, Tipton VJ. Review of Haemaphysalis (kaiseriana) Longicornis Neumann (resurrected) of Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Fiji, Japan, Korea, and Northeastern China and USSR, and its parthenogenetic and bisexual populations (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). J Parasitol. 1968;54:1197–213. 10.2307/3276992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard CB, Occi J, Bonilla DL, Egizi AM, Fonseca DM, Mertins JW, et al. Multistate infestation with the exotic diesase-vector tick Haemaphysalis longicornis—United States, August 2017–September 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1310–3. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6747a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z, Yang X, Bu F, Yang X, Liu J. Morphological, biological and molecular characteristics of bisexual and parthenogenetic Haemaphysalis longicornis. Vet Parasitol. 2012;189:344–52. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo L-M, Zhao L, Wen H-L, Zhang Z-T, Liu J-W, Fang L-Z, et al. Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks as reservoir and vector of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1770–6. 10.3201/eid2110.150126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinuki Y, Ishiwata K, Yamaji K, Takahashi H, Morita E. Haemaphysalis longicornis tick bites are a possible cause of red meat allergy in Japan. Allergy. 2016;71:421–5. 10.1111/all.12804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rainey T, Occi JL, Robbins RG, Egizi A. Discovery of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) parasitizing a sheep in New Jersey, United States. J Med Entomol. 2018;55:757–9. 10.1093/jme/tjy006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver JH Jr. Parthenogenesis in mites and ticks (Arachnida: Acari). Am Zool. 1971;11:283–99. 10.1093/icb/11.2.283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath A. Biology, ecology and distribution of the tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Zealand. N Z Vet J. 2016;64:10–20. 10.1080/00480169.2015.1035769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherst RW, Moorhouse DE. The seasonal incidence of Ixodid ticks on cattle in an elevated area of South-Eastern Queensland. Aust J Agric Res. 1972;23:195–204. 10.1071/AR9720195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JL, Kim HC, Coburn JM, Chong ST, Chang NW, Robbins RG, et al. Tick surveillance in two southeastern provinces, including three metropolitan areas, of the Republic of Korea during 2014. Systematic and Applied Acarology. 2017;22:271–88. 10.11158/saa.22.2.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chitimia L, Lin RQ, Cosoroaba I, Wu XY, Song HQ, Yuan ZG, et al. Genetic characterization of ticks from southwestern Romania by sequences of mitochondrial cox1 and nad5 genes. Exp Appl Acarol. 2010;52:305–11. 10.1007/s10493-010-9365-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JK, Stokes JV, Moraru GM, Harper AB, Smith CL, Wills RW, et al. Transmission of Amblyomma maculatum-associated Rickettsia spp. during cofeeding on cattle. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018;18:511–8. 10.1089/vbz.2017.2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.States SL, Huang CI, Davis S, Tufts DM, Diuk-Wasser MA. Co-feeding transmission facilitates strain coexistence in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. Epidemics. 2017;19:33–42. 10.1016/j.epidem.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heath ACG, Tenquist JD, Bishop DM. Goats, hares, and rabbits as hosts for the New Zealand cattle tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. NZ J Zool. 1987;14:549–55. 10.1080/03014223.1987.10423028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]