Abstract

DNA damage–mediated activation of extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) can regulate both cell survival and cell death. We show here that ERK activation in this context is biphasic and that early and late activation events are mediated by distinct upstream signals that drive cell survival and apoptosis, respectively. We identified the nuclear kinase mitogen-sensitive kinase 1 (MSK1) as a downstream target of both early and late ERK activation. We also observed that activation of ERK→MSK1 up to 4 h after DNA damage depends on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), as EGFR or mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK)/ERK inhibitors or short hairpin RNA–mediated MSK1 depletion enhanced cell death. This prosurvival response was partially mediated through enhanced DNA repair, as EGFR or MEK/ERK inhibitors delayed DNA damage resolution. In contrast, the second phase of ERK→MSK1 activation drove apoptosis and required protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) but not EGFR. Genetic disruption of PKCδ reduced ERK activation in an in vivo irradiation model, as did short hairpin RNA–mediated depletion of PKCδ in vitro. In both models, PKCδ inhibition preferentially suppressed late activation of ERK. We have shown previously that nuclear localization of PKCδ is necessary and sufficient for apoptosis. Here we identified a nuclear PKCδ→ERK→MSK1 signaling module that regulates apoptosis. We also show that expression of nuclear PKCδ activates ERK and MSK1, that ERK activation is required for MSK1 activation, and that both ERK and MSK1 activation are required for apoptosis. Our findings suggest that location-specific activation by distinct upstream regulators may enable distinct functional outputs from common signaling pathways.

Keywords: apoptosis, protein kinase C (PKC), signal transduction, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), DNA damage, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), cell signaling, kinase cascade, mitogen-sensitive kinase (MSK)

Introduction

Irradiation (IR)3 and chemotherapy are widely used for the treatment of cancer; however, adjacent healthy tissues can also be damaged, including the mucosal tissues of the gut and oral cavity. Such collateral tissue damage can result in significant comorbidities and, in some cases, limit the course of therapy (1). As IR and chemotherapies work in part by inducing apoptosis, modulation of apoptotic mediators specifically in nontumor cells could offer protection against collateral tissue damage, resulting in improved quality of life and, in some cases, better tumor eradication (2–4). PKCδ is a ubiquitously expressed serine–threonine kinase that controls a wide variety of cell functions, including proliferation, cell survival, invasion and migration, and cell death (5). PKCδ has been identified as an important mediator of DNA damage–induced apoptosis, and our laboratory and others have shown that inhibition of PKCδ activation can reduce IR and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in vitro and toxicity to nontumor tissues in vivo (6–9). Remarkably, inhibition of PKCδ has been shown to preserve salivary gland function in mice exposed to head and neck IR but did not impact treatment of the tumor (8). This supports previous data from our laboratory that suggests that, in contrast to normal cells, in some tumor cells PKCδ does not regulate apoptosis but may instead have a prosurvival role (10–12).

Studies from our laboratory indicate that nuclear PKCδ is required for apoptosis, suggesting that PKCδ function may be dictated in part by its subcellular localization (13–18). Further, most studies suggest that PKCδ does not directly regulate the apoptotic machinery but may instead integrate upstream signals to regulate cell fate decisions in response to cell distress or damage (2, 17, 19, 20). In this regard, PKCδ has been shown to regulate signaling through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinases, and p38 MAPKs), primarily downstream of growth factor receptors (21–23) but also in response to DNA damage (24).

The MEK/ERK pathway has well-established roles in proliferation and survival and regulates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to DNA damage (21, 22, 25–27). In damaged cells, the duration, magnitude, and subcellular localization of ERK1/2 activation may be critical in determining whether the outcome is prosurvival or pro-apoptotic (21, 25). We show that activation of ERK in response to DNA damage agents is biphasic, consisting of an early prosurvival phase and a later pro-apoptotic phase. These phases are mediated by distinct upstream regulators, with EGFR activating ERK in the early phase and PKCδ activating late-phase ERK. Furthermore, we identify a unique ERK→MSK1 signaling module regulated by nuclear PKCδ that is essential for apoptosis. Our study shows that DNA damage induces temporally distinct prosurvival and pro-apoptotic signaling pathways and suggest that the functional output of ERK→MSK1 activation in response to DNA damage is regulated, at least in part, by the upstream activator.

Results

In response to DNA damage, biphasic activation of ERK drives survival and apoptosis

ParC5 rat parotid acinar cells provide a useful model to study DNA damage–induced cell death, as their response to irradiation is similar to that observed in salivary acinar cells in vivo (3). In parC5 cells treated with etoposide, ERK activation is biphasic, with an initial peak at around 2 h and a second peak at 6–8 h (Fig. 1A). Similar results were seen when cells were treated with IR (Fig. 2B). Quantification of pERK/ERK across multiple time points from three independent experiments is shown in Fig. 1B. To determine whether one or both of peaks of ERK activity are required for apoptosis, we assayed activation of caspase-3 in cells pretreated with PD98059, which inhibits MEK, the upstream regulator of ERK. When apoptosis was assayed 2–4 h after addition of etoposide, pretreatment with PD98059 resulted in an up to 4-fold increase in apoptosis, demonstrating that early activation of ERK conveys a survival signal (Fig. 1C). However, at 8 h, PD98059 slightly suppresses apoptosis. Consistent with this, when parC5 cells were pretreated with PD98059 or a second MEK inhibitor, U0126, and then treated with etoposide for 18 h, apoptosis was significantly reduced compared with cells treated with etoposide alone (Fig. 1D). Similar results were seen with pretreatment using MEK inhibitors followed by IR (Fig. 1E). These data demonstrate that ERK activation in response to DNA damage can drive both survival and apoptosis and that these distinct functional outputs may be dictated by the kinetics of activation.

Figure 1.

Biphasic activation of ERK drives survival and apoptosis. A, ParC5 cells were treated with 50 μm etoposide for the indicated times (hours). Cells were harvested and immunoblotted for pERK and stripped and reprobed for ERK and β-actin. B, quantitation by densitometry of three separate experiments similar to that shown in A. Data represent pERK/ERK/actin ratios ± S.E. Statistics represent one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey's multiple comparisons. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05. C, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control (black columns) or 10 μm PD98059 (gray columns) prior to addition of 50 μm etoposide for the indicated times (hours). D, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control (black columns), 20 μm PD98059 (dark gray columns), or 20 μm U0126 (white columns) prior to addition of 0, 0.5, 5, or 50 μm etoposide for 18 h. E, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control (black columns), 20 μm or 40 μm PD98059 (dark gray columns), or 20 μm or 40 μm U0126 (light gray and white columns) and then left untreated or treated with 10 Gy of IR. Cells were harvested 48 h after IR. Caspase-3 activity (C and E) and DNA fragmentation (D) were assayed as described under “Experimental procedures.” Data shown are representative experiments; statistics represent two-way ANOVA for comparison of time point or treatment with the corresponding control. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent S.E. from triplicate samples.

Figure 2.

EGFR activation of ERK promotes cell survival. A, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control or 600 nm gefitinib prior to addition of 50 μm etoposide for the indicated times (hours). Cells were harvested and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. B, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control or 300 nm gefitinib prior to treatment with 10 Gy of IR. Cells were harvested at the indicated times (hours) post-IR and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. C, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control or 300 nm gefitinib or afatinib prior to addition of 50 μm etoposide. Cells were harvested for measurement of caspase-3 activity at the indicated times (hours). D, ParC5 cells were pretreated with DMSO, 300 nm gefitinib, or 20 μm PD98059 prior to irradiation with 10 Gy of IR. Following IR, cells were harvested at various time points (hours) and prepared using a neutral comet assay according to the Trevigen comet assay protocol. Data shown are representative experiments. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA for comparison of time point or treatment with the corresponding control. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05.

Activation of EGFR in response to DNA damage promotes cell survival

Activation of EGFR occurs rapidly but transiently in response to DNA damage, with kinetics similar to the early phase of ERK activation (Fig. 2A, left). Early activation of ERK requires EGFR activity, as it is abolished in cells pretreated with gefitinib (Fig. 2A, right). Notably, EGFR inhibition only blocked early activation of ERK (up to 4 h), with no effect on late activation of ERK (Fig. 2, A and B). However, both EGFR inhibitors increased apoptosis up to 8 h after addition of etoposide (Fig. 2C), similar to that seen with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (Fig. 1C).

Previous studies have suggested a role for EGFR and ERK in regulation of DNA double-stranded break repair, which could in part explain the prosurvival phenotype we observed (29–33). To test this, we assayed DNA damage using a comet assay in cells treated with IR and pretreated with gefitinib or PD98059. Although untreated cells and inhibitor-treated cells had a similar amount of DNA damage at 15 min, DNA damage was increased in inhibitor-treated cells 30 min and 1 h after IR compared with the control, indicating a delay in DNA repair with inhibition of ERK or EGFR (Fig. 2D). Our study shows that prosurvival signaling through EGFR→ERK correlates with enhanced DNA repair in the first few hours after DNA damage. This could occur via direct regulation of DNA repair by EGFR→ERK or through an indirect mechanism, such as prolonged activation of cell cycle checkpoints to allow repair.

PKCδ activation of ERK in response to DNA damage drives apoptosis

PKCδ is a pro-apoptotic kinase that also regulates ERK signaling in some biological contexts (5). We investigated the kinetics and magnitude of ERK activation in parC5 cells depleted of PKCδ using shRNA (Fig. 3A) and in salivary gland tissue lysates from PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− mice that were treated with IR to the head and neck (Fig. 3B). In PKCδ+/+ mice, the pattern of ERK activation by IR was similar to that observed in cells treated with etoposide, with two phases of ERK activation at 2 and 6 h (Fig. 3B). In PKCδ−/− mice, both phases of ERK activation were reduced; quantitation of pERK/ERK by densitometry shows that the second peak (6 h) was more dramatically reduced than the first peak (2 h) (45% versus 80% reduction, respectively) (Fig. 3B). This suggests that depletion of PKCδ primarily inhibits the “pro-apoptotic” phase of ERK activation. To confirm this, we assayed ERK activation in parC5 cells depleted of PKCδ with shRNA (δ561) or a scrambled shRNA (SCR). Similar to PKCδ−/− mice, depletion of PKCδ resulted in a small decrease in the early phase of ERK activation by etoposide at 2 h and a more dramatic effect on later activation of ERK at 6 h (Fig. 3A). Our data suggest that PKCδ primarily regulates the second phase of ERK activation to drive apoptosis, independent of prosurvival signaling by ERK. Depletion of PKCδ also slightly decreased activation of EGFR in cells treated with etoposide (Fig. 3A), consistent with partial inhibition of the early phase of ERK activation (Fig. 3, A and B). To directly ask whether PKCδ contributes to cell survival in response to DNA damage, we analyzed caspase-3 activation in parC5 cells depleted of PKCδ. Depletion of PKCδ using three independent shRNAs suppressed apoptosis at all time points, indicating that PKCδ drives apoptosis and does not play a role in the early prosurvival effect through EGFR→ERK (Fig. 3C). Our study demonstrates that, in response to DNA damage, PKCδ activation of ERK appears to solely drive cell death signaling.

Figure 3.

Nuclear PKCδ activates ERK to drive apoptosis. A, ParC5 cells stably expressing either PKCδ shRNA (δ561) or a scrambled control were treated with 50 μm etoposide (Etop) for the indicated times (hours). Lysates were immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. B, 6-week-old female PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− mice were irradiated with 5 Gy of IR and harvested at the indicated times (hours) post-IR. Protein lysates were prepared from the parotid gland and immunoblotted for pERK, ERK, and PKCδ. The graph shows relative densitometry units of pERK normalized to total ERK bands, with gray and black columns indicating PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/−, respectively. C, ParC5 cells stably expressing either PKCδ shRNA (δ561) or a scrambled control were treated with 50 μm etoposide for the indicated times (hours). Lysates were assayed for caspase-3 activity. D, ParC5 cells were transfected with constructs expressing GFP, PKCδWT, or PKCδNLS for the indicated times (hours). E, ParC5 cells were transfected with constructs expressing GFP or GFP-PKCδCF for 24 h. For both D and E, cells were harvested and immunoblotted for GFP, pERK, ERK, or β-actin. F, ParC5 cells were transduced with either Ad-GFP or Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS and plated in the presence of 10 μm U0126 (gray columns) or 20 μm PD98059 (white columns) or treated with the DMSO control (black columns). Cells were harvested and assayed 48 h post-transduction for caspase-3 activity. Data shown are representative experiments. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA for comparison of time point or treatment with the corresponding control. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05.

Nuclear translocation of PKCδ is required for DNA damage–induced apoptosis, and direct targeting of PKCδ to the nucleus induces apoptosis (13, 16). Therefore, we investigated the hypothesis that the pro-apoptotic phase of ERK activation is mediated through nuclear PKCδ. ParC5 cells were transduced with Ad-GFP, Ad-GFP-PKCδWT, or Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS, a construct where we added an SV40 NLS to PKCδ, resulting in direct targeting of PKCδ to the nucleus (15, 16). Remarkably, expression of either Ad-GFP-PKCδWT or Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS resulted in increased ERK activation (Fig. 3D). PKCδCF is a caspase-cleaved form of PKCδ generated in response to DNA damage and is a potent inducer of apoptosis (28). PKCδCF is constitutively nuclear because of loss of constraints imposed by the regulatory domain of the kinase (16). As shown in Fig. 3E, expression of pEGFPN1-PKCδCF robustly induces pERK, further supporting our conclusion that nuclear localization of PKCδ is sufficient to activate ERK. To determine whether ERK activation is required for apoptosis induced by nuclearly targeted PKCδ, parC5 cells transduced with Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS were treated with the MEK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126. Expression of Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS induced caspase-3 activation, as shown previously, and this could be suppressed by both MEK inhibitors, indicating a requirement for ERK activation downstream of PKCδ for induction of apoptosis (Fig. 3F).

ERK activates MSK1 in response to DNA damage

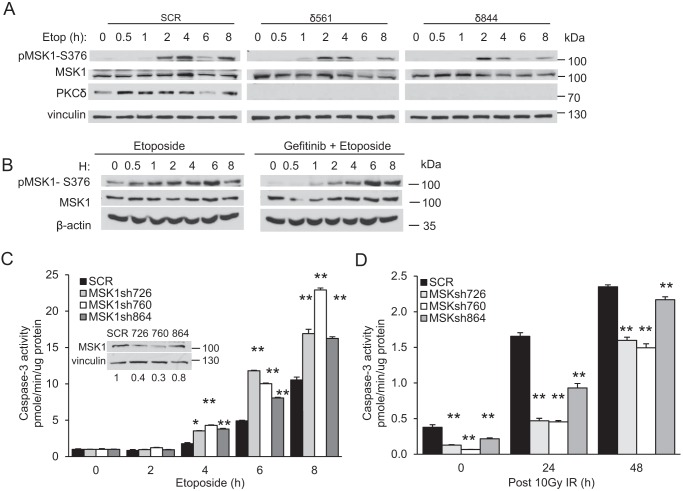

Our study shows that nuclear PKCδ induces apoptosis via activation of ERK; however, downstream targets of ERK that drive apoptosis are largely unknown. MSK1/2 kinases are activated downstream of ERK and p38 and predominantly localize to the nucleus, where they phosphorylate transcription factors and regulate chromatin remodeling (29–31). In response to DNA damage, MSK1 is activated in a biphasic manner with kinetics similar to what we have shown previously for ERK (Figs. 4A and 1A). Activation of MSK1 in δ561 and δ844 cells is suppressed compared with SCR cells (Fig. 4A). Similar to ERK (Fig. 3, A and B), loss of PKCδ suppresses late MSK1 activation (6 to 8 h) to a greater extent than early activation (2 to 4 h) (Fig. 4A), whereas pretreatment with gefitinib only suppresses early activation of MSK1 (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

ERK activates MSK1 in response to DNA damage. A, ParC5 cells stably expressing either control (SCR) or PKCδ shRNA (δ561 or δ844) were treated with 50 μm etoposide (Etop) for the indicated times (hours). Cells were harvested and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. B, ParC5 cells were pretreated with the DMSO control or 600 nm gefitinib prior to addition of 50 μm etoposide for the indicated times (hours). Cells were harvested and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. C and D, ParC5 cells stably expressing either SCR control or MSK1 shRNA were treated with 50 μm etoposide (C) or irradiated with 10 Gy of IR (D). Cells were harvested for caspase-3 activity at the indicated times. The blot in C demonstrates the magnitude of MSK1 depletion in the cells used in C and D. Data shown are representative experiments. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA for comparison of time point or treatment with the corresponding control. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05.

Our observation that MSK1 and ERK activation are co-regulated in response to DNA damage suggests that activation of MSK1 may contribute to prosurvival signaling through EGFR→ERK and pro-apoptotic signaling through PKCδ→ERK. Indeed, depletion of MSK1 using three unique shRNAs results in increased apoptosis up to 8 h after addition of etoposide, indicating that, like ERK, early activation of MSK1 is prosurvival (Fig. 4C). In contrast, depletion of MSK1 dramatically decreases cell death 24–48 h after IR (Fig. 4D), analogous to what we described previously when MEK/ERK was inhibited (Fig. 1E). Our data support a model whereby, in response to DNA damage, EGFR activation of ERK and MSK1 promotes cell survival in the first few hours after DNA damage, whereas late activation of MSK1 downstream of PKCδ→ERK may be required for apoptosis.

PKCδ drives DNA damage–induced apoptosis via ERK→MSK1

As targeting PKCδ to the nucleus activates ERK (Fig. 3D), we asked whether nuclearly targeted PKCδ also activates MSK1 as evidenced by phosphorylation on Ser-376. As seen in Fig. 5A, transduction of parC5 cells with Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS results in activation of MSK1. MSK1 activation by Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS could be suppressed by pretreatment with the MEK/ERK inhibitor PD98059 but not the p38MAPK inhibitor SB20358 (Fig. 5B). Unexpectantly, inhibition of p38MAPK with SB20358 increased pERK in both Ad-GFP and Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS transduced cells; however, pMSK1 was only increased in cells that were also transduced with Ad-PKCδNLS (Fig. 5B). Notably, p38MAPK inhibition has no effect on etoposide induced apoptosis (Fig. S1), indicating that this pathway does not contribute to apoptotic signaling through PKCδ.

Figure 5.

PKCδ drives DNA damage–induced apoptosis via ERK→MSK1. A, ParC5 cells were transduced with Ad-GFP or Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS (m.o.i. 200) for 24 h. Cells were harvested at the indicated times post-IR and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. B, ParC5 cells were pretreated with 20 μm PD98059 (PD), 5 μm SB203580 (SB), or a combination of both concurrently with transduction of either Ad-GFP or Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS adenovirus (m.o.i. 200). Cells were then harvested and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. C and D, ParC5 cells stably expressing either SCR control or MSK1 shRNA were either left untransfected or transfected with GFP, GFP-PKCδNLS (C), or GFP-PKCδCF (D) plasmid for 24 h. Cells were harvested and assayed for caspase-3 activity. Data shown are representative experiments. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA for comparison of time point or treatment with the corresponding control. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05.

To verify a pro-apoptotic function for MSK1 downstream of nuclear PKCδ, we analyzed the ability of Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS to induce apoptosis in parC5 cells in which MSK1 was depleted with shRNA. Apoptosis driven by expression of Ad-GFP-PKCδNLS was suppressed in cells depleted of MSK1, and the degree of suppression was correlated with the amount of MSK1 depletion (Figs. 5C and 4C). Finally, we asked whether MSK1 is required for apoptosis induced by PKCδCF. Expression of pEGFPN1-PKCδCF potently induced apoptosis in control parC5 cells, but apoptosis was severely reduced in cells depleted of MSK1 (Fig. 5D).

Our study defines a common ERK→MSK1 pathway that, when activated by EGFR in response to DNA damage, drives cell survival but when activated by nuclear PKCδ drives apoptosis (Fig. 6). Moreover, we define a nuclear specific function for PKCδ in driving apoptosis through ERK→MSK1. Activation of ERK→MSK1 for survival versus apoptosis is temporally distinct, which may reflect access to specific upstream regulators.

Figure 6.

Biphasic activation of ERK and MSK1 in response to DNA damage regulates survival and apoptosis. Our study defines a common ERK→MSK1 pathway that, when activated by EGFR in response to DNA damage, drives cell survival but when activated by nuclear PKCδ drives apoptosis.

Discussion

We show that, in the context of DNA damage, activation of ERK can have a dramatically different biological outcome depending on when, how, and where in the cell it is activated. We identify temporally distinct prosurvival and pro-apoptotic signaling pathways that are both mediated through ERK→MSK1. Prosurvival signaling through EGFR→ERK enhances DNA repair in the first few hours after DNA damage through a PKCδ-independent pathway. In contrast, pro-apoptotic signaling through ERK occurs 6–8 h after DNA damage and is independent of EGFR but dependent on PKCδ. Furthermore, our study identifies a unique ERK→MSK1 signaling module regulated by nuclear PKCδ that is essential for DNA damage–induced apoptosis. Our study suggests that location-specific activation by distinct upstream regulators may enable common signaling pathways to have unique functional outputs.

The MEK/ERK pathway has well established roles in proliferation and survival and paradoxically regulates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, particularly in response to DNA damage (21, 22, 25–27). We show that biphasic activation of ERK in response to DNA-damaging agents sequentially activates prosurvival and pro-apoptotic signaling pathways. EGFR activation is required for the early, prosurvival phase of ERK activation in response to DNA damage. Notably, pretreatment of cells with gefitinib only suppressed the early phase of ERK activation, confirming that early and late ERK activation have distinct upstream regulators. The kinetics of activation of EGFR and early activation of ERK are similar to the kinetics of DNA repair, as assayed by comet, supporting published studies that show a role for EGFR in the regulation of IR-induced DNA double-stranded break repair (32–35). In some cases, EGFR regulation of DNA repair is associated with nuclear translocation of EGFR, and EGFR has been shown to interact with and regulate DNA repair machinery, including DNA-dependent protein kinase (32). EGFR can also regulate chromatin remodeling and DNA repair through tyrosine phosphorylation of histone H4 (36).

The second, pro-apoptotic phase of ERK activation is largely dependent on PKCδ and independent of EGFR. A pro-apoptotic function for PKCδ is supported by extensive studies in vitro and in vivo that demonstrate a role for PKCδ in apoptosis in response to many types of cell and tissue damage (3, 4, 10, 17, 18, 20). Furthermore, our study confirms that PKCδ does not contribute to cell survival signaling in response to DNA damage, as depletion of PKCδ suppresses the apoptotic response at all time points (Fig. 3C). However, the fact that ERK activation is only partially suppressed in irradiated tissues from a δ knockout mouse supports data suggesting that other pathways, such as Akt and NF-κB, can contribute to ERK activation in response to DNA damage (22).

MSK1/2 kinases, members of the AGC kinase family, are activated by the ERK1/2 and p38 pathways in response to extracellular stimuli and predominantly localize to the nucleus (29–31). Activation of MSK1/2 results in phosphorylation of transcription factors required for immediate-early gene expression and chromatin-associated proteins, including histone H3 (30, 37–39). In our study, MSK1 was activated by DNA damage with similar kinetics as ERK, and early MSK1 activation, like early ERK activation, was EGFR-dependent. We show that early activation of MSK1 through an EGFR→ERK pathway promotes cell survival, consistent with studies that show a role in stress resistance (30) and enhanced apoptosis in an MSK1/2 knockout mouse (40). Given its known role in chromatin modification, it is interesting to speculate that MSK1 could contribute to the increase in EGFR-induced DNA repair we observed in the first few hours after DNA damage.

Notably, prosurvival signaling through EGFR→ERK→MSK1 is transient; however, our study does not address how this signal is turned off. Nyati et al. (41) show that ataxia telangiectasia–mutated (ATM) activation can down-regulate ERK through activation of dual specificity phosphatase-1 (DUSP1), also known as MKP-1. Likewise, nuclear localized DUSPs, such as DUSP5, are candidates for regulation of the nuclear level of activated ERK (42). Inhibition of ERK activation through DUSP6 has been shown to enhance the DNA damage response and increase sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors (43). Finally, it is possible that prosurvival ERK signaling does not need to be “turned off” for PKCδ to induce pro-apoptotic ERK signaling, as sustained ERK activation has been shown to induce apoptosis (21, 25).

As PKCδ is ubiquitously expressed and regulates a wide variety of cell functions in addition to apoptosis, it is important to understand how apoptotic specific signaling by PKCδ is mediated (5). We have shown that nuclear accumulation of PKCδ is necessary for apoptosis in response to DNA-damaging agents and sufficient for apoptosis in many cell types (13–18). This suggests that the subcellular localization of PKCδ in the nucleus may dictate the apoptosis-specific functions of PKCδ. Conversely, it is tempting to speculate that localization of PKCδ in other cellular compartments may dictate other functions, such as proliferation and cell migration. In this study, we use a constitutively nuclear targeted form of PKCδ to address the role of nuclear PKCδ in the regulation of pro-apoptotic signaling through ERK→MSK1. Expression of PKCδNLS potently activates ERK and MSK1, and activation of these kinases is necessary for PKCδNLS to induce apoptosis (Fig. 5). Likewise, expression of δCF also induces ERK and apoptosis through an MSK1-dependent pathway (Figs. 3E and 5D). Although our study shows that nuclear targeting of PKCδ is sufficient to activate ERK→MSK1, it should be noted that PKCδWT can also activate ERK (Fig. 3D). Thus we cannot rule out a role for PKCδ in activating cytoplasmic ERK→MSK1. Indeed, PKCδ is a known effector of growth factor signaling and has been shown to activate ERK in this context (9).

MSK1 is largely associated with cell survival through regulation of transcription of stress-related genes (34). This is consistent with the prosurvival role we demonstrate for early activation of MSK1 (Fig. 4C). Early activation of MSK1, like ERK, occurs independently of PKCδ but depends on EGFR (Fig. 4, A and B). As MSK1 is predominantly a nuclear kinase, further studies are needed to clarify whether EGFR activates a cytoplasmic or nuclear pool of MSK1. Our study defines an additional role for MSK1 in the regulation of cell death and shows that it is a component of the signaling cascade regulated by nuclear PKCδ that activates the apoptotic response. How PKCδ regulates nuclear ERK→MSK1 signaling is not known, although unpublished studies from our laboratory suggest that PKCδ may regulate the abundance of nuclear and cytoplasmic DUSPs. Likewise, additional studies will be needed to decipher how the ERK→MSK1 pathways induce apoptosis. It is tempting to speculate that, as a chromatin-modifying kinase, MSK1 could contribute to DNA repair by regulating the accessibility of damaged DNA to repair complexes.

Our identification of an ERK→MSK1 signaling cascade that can regulate cell survival or apoptosis, depending on how and where it is activated, suggests a common mechanism that can be tuned according to the desired outcome. Conceivably, these pathways could also have shared targets that promote different functional outcomes dictated by the specific biological context. Clarification of prosurvival and pro-apoptotic targets of ERK→MSK1 is essential to maximize the therapeutic potential of targeting these pathways.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and generation of shRNA stable knockdown cell lines

Culture of the parC5 cell line has been described previously (44). ParC5 cells were stably depleted of target protein by transducing with either a nontargeting lentiviral shRNA (SCR) or lentiviral shRNAs against Protein Kinase C Delta TRCN0000280561 (δ561), TRCN0000022844 (δ844), TRCN0000022848 (δ848) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or Rps6ka5 (MSK1) Smartvector rat lentiviral set V3SR11245-14EG314384 (MSK1sh726, MSK1sh760, and MSK1sh864) (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/high-glucose medium (Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT; SH30243.02) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, F2442) and transfected using FuGENE 6 (Promega, Madison, WI) to produce a lentivirus containing the shRNA described above. The MEK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 and the P38 inhibitor SB203580 were obtained from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN). The EGFR inhibitors gefitinib and afatinib were obtained from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). All inhibitors were added 30 min prior to addition of either 50 μm etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich) or exposure to γ-irradiation from a cesium-137 source.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (3). Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were stained with Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich, P3504) following transfer to confirm equal transfer and loading. The following antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA): phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr-202/Tyr-204) (CST4370), p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (CST4696), phospho-EGFR (Tyr-1068) (CST3777), EGFR (CST2232), phospho-MSK1 (Ser-376) (CST9591), p38 (CST9212), PKCδ (CST2058), and vinculin (CST13901). Antibodies to β-actin (ab49900) and GFP (ab290) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies to phospho-p38 (Thr-180, Tyr-182; NB500-138) and MSK1 (bs-2995R) were obtained from Novus (Centennial, CO) and Bioss Antibodies Inc. (Woburn, MA), respectively. Area density analysis was performed on the indicated blots using VisionWorks software from Analytikjena.

Comet assay

Materials for the comet assay were purchased from Trevigen (Gaithersburg, MD). ParC5 cells were treated with DMSO, 300 nm gefitinib, or 20 μm PD98059 and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h prior to irradiation using a cesium-137 source (10 Gy). Following IR, cells were harvested at the indicated times for measurement of DNA damage using the neutral comet assay according to the Trevigen comet assay protocol. Images were analyzed by Trevigen Comet Analysis Software (version 1.3d). Tail moment was used to quantify DNA damage.

Expression of PKCδ constructs

Overexpression of all PKCδ constructs was achieved using either adenoviral transduction or plasmid transfection, as described previously (13, 16). For adenoviral infection, parC5 cells were transduced with Ad-PKCδWT-GFP, Ad-PKCδNLS-GFP, or Ad-GFP at m.o.i. ranging from 50 to 200 focus-forming units/cell. Infection was allowed to proceed for 24–48 h, as indicated. Transient transfections of plasmid pEGFPN1 and pEGFPN1-PKCδ constructs (δWT, δNLS, and δCF) were performed using Jetprime transfection reagent (Genesee Scientific, El Cajon, CA).

In vivo irradiation

C57Bl/6 PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− mice (45) were maintained at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in accordance with laboratory animal care guidelines and protocols and with approval of the University of Colorado Denver Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Six- to eight-week-old female mice were anesthetized as described, and the head and neck regions were irradiated using a cesium-137 source, whereas the remainder of the body was shielded with lead. Salivary glands were harvested and tissue extracts prepared as described previously (3).

Analysis of apoptosis in vitro

Active caspase-3 was detected with the Caspase-3 Cellular Activity Assay Kit PLUS (Biomol, Farmingdale, NY; BML-ALK7030001), which uses N-acetyl-DEVD-p-nitroaniline as a substrate, according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragmentation was assayed using the Cell Death Detection ELISA Plus Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistics

Data shown in figures are representative experiments repeated a minimum of three times. Error bars indicate standard error. Caspase-3 activity, DNA fragmentation, and comet assays were designed with triplicate biological samples. Statistics were determined using GraphPad Prism 7 software. A two-way ANOVA (α = 0.05) with Dunnett's multiple comparisons (**, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05) was performed within each time point or treatment, comparing each column (gray or white) with the corresponding control (black).

Author contributions

A. M. O. and T. A. data curation; A. M. O., T. A., and M. E. R. formal analysis; A. M. O. validation; A. M. O. and T. A. investigation; A. M. O. visualization; A. M. O. and T. A. methodology; A. M. O. and M. E. R. project administration; A. M. O., T. A., and M. E. R. writing-review and editing; T. A. and M. E. R. conceptualization; T. A. and M. E. R. supervision; M. E. R. funding acquisition; M. E. R. writing-original draft.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by NIDCR, National Institutes of Health Grants R01DE027517 and R01 DE015648 (to A. M. O., T. A., and M. E. R.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Fig. S1.

- IR

- irradiation

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal–regulated kinase

- MEK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- SCR

- scrambled

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- NLS

- nuclear localization sequence

- DUSP

- dual specificity phosphatase

- Gy

- gray

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection.

References

- 1. Vissink A., Mitchell J. B., Baum B. J., Limesand K. H., Jensen S. B., Fox P. C., Elting L. S., Langendijk J. A., Coppes R. P., and Reyland M. E. (2010) Clinical management of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer patients: successes and barriers. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78, 983–991 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen-Petersen B. L., Miller M. R., Neville M. C., Anderson S. M., Nakayama K. I., and Reyland M. E. (2010) Loss of protein kinase Cδ alters mammary gland development and apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 1, e17 10.1038/cddis.2009.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Humphries M. J., Limesand K. H., Schneider J. C., Nakayama K. I., Anderson S. M., and Reyland M. E. (2006) Suppression of apoptosis in the protein kinase Cδ null mouse in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9728–9737 10.1074/jbc.M507851200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leitges M., Mayr M., Braun U., Mayr U., Li C., Pfister G., Ghaffari-Tabrizi N., Baier G., Hu Y., and Xu Q. (2001) Exacerbated vein graft arteriosclerosis in protein kinase Cδ-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1505–1512 10.1172/JCI200112902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reyland M. E., and Jones D. N. (2016) Multifunctional roles of PKCδ: opportunities for targeted therapy in human disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 165, 1–13 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arany S., Benoit D. S., Dewhurst S., and Ovitt C. E. (2013) Nanoparticle-mediated gene silencing confers radioprotection to salivary glands in vivo. Mol. Ther. 21, 1182–1194 10.1038/mt.2013.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pabla N., Dong G., Jiang M., Huang S., Kumar M. V., Messing R. O., and Dong Z. (2011) Inhibition of PKCδ reduces cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity without blocking chemotherapeutic efficacy in mouse models of cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2709–2722 10.1172/JCI45586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wie S. M., Adwan T. S., DeGregori J., Anderson S. M., and Reyland M. E. (2014) Inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) protects the salivary gland from radiation damage. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 10900–10908 10.1074/jbc.M114.551366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wie S. M., Wellberg E., Karam S. D., and Reyland M. E. (2017) Tyrosine kinase inhibitors protect the salivary gland from radiation damage by inhibiting activation of protein kinase C-δ. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16, 1989–1998 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allen-Petersen B. L., Carter C. J., Ohm A. M., and Reyland M. E. (2014) Protein kinase Cδ is required for ErbB2-driven mammary gland tumorigenesis and negatively correlates with prognosis in human breast cancer. Oncogene 33, 1306–1315 10.1038/onc.2013.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohm A. M., Tan A. C., Heasley L. E., and Reyland M. E. (2017) Co-dependency of PKCδ and K-Ras: inverse association with cytotoxic drug sensitivity in KRAS mutant lung cancer. Oncogene 36, 4370–4378 10.1038/onc.2017.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Symonds J. M., Ohm A. M., Carter C. J., Heasley L. E., Boyle T. A., Franklin W. A., and Reyland M. E. (2011) Protein kinase Cδ is a downstream effector of oncogenic K-ras in lung tumors. Cancer Res. 71, 2087–2097 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeVries-Seimon T. A., Ohm A. M., Humphries M. J., and Reyland M. E. (2007) Induction of apoptosis is driven by nuclear retention of protein kinase Cδ. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22307–22314 10.1074/jbc.M703661200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adwan T. S., Ohm A. M., Jones D. N., Humphries M. J., and Reyland M. E. (2011) Regulated binding of importin-α to protein kinase Cδ in response to apoptotic signals facilitates nuclear import. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35716–35724 10.1074/jbc.M111.255950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeVries T. A., Kalkofen R. L., Matassa A. A., and Reyland M. E. (2004) Protein kinase Cδ regulates apoptosis via activation of STAT1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45603–45612 10.1074/jbc.M407448200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeVries T. A., Neville M. C., and Reyland M. E. (2002) Nuclear import of PKCδ is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J. 21, 6050–6060 10.1093/emboj/cdf606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matassa A. A., Carpenter L., Biden T. J., Humphries M. J., and Reyland M. E. (2001) PKCδ is required for mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in salivary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29719–29728 10.1074/jbc.M100273200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matassa A. A., Kalkofen R. L., Carpenter L., Biden T. J., and Reyland M. E. (2003) Inhibition of PKCα induces a PKCδ-dependent apoptotic program in salivary epithelial cells. Cell Death Differ. 10, 269–277 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu H., Lu Z. G., Miki Y., and Yoshida K. (2007) Protein kinase Cδ induces transcription of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene by controlling death-promoting factor Btf in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 8480–8491 10.1128/MCB.01126-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reyland M. E., Anderson S. M., Matassa A. A., Barzen K. A., and Quissell D. O. (1999) Protein kinase Cδ is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19115–19123 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cagnol S., and Chambard J. C. (2010) ERK and cell death: mechanisms of ERK-induced cell death: apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. FEBS J. 277, 2–21 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tentner A. R., Lee M. J., Ostheimer G. J., Samson L. D., Lauffenburger D. A., and Yaffe M. B. (2012) Combined experimental and computational analysis of DNA damage signaling reveals context-dependent roles for Erk in apoptosis and G1/S arrest after genotoxic stress. Mol. Syst. Biol. 8, 568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Plotnikov A., Zehorai E., Procaccia S., and Seger R. (2011) The MAPK cascades: signaling components, nuclear roles and mechanisms of nuclear translocation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1619–1633 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lomonaco S. L., Kahana S., Blass M., Brody Y., Okhrimenko H., Xiang C., Finniss S., Blumberg P. M., Lee H. K., and Brodie C. (2008) Phosphorylation of protein kinase Cδ on distinct tyrosine residues induces sustained activation of Erk1/2 via down-regulation of MKP-1: role in the apoptotic effect of etoposide. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17731–17739 10.1074/jbc.M801727200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhuang S., and Schnellmann R. G. (2006) A death-promoting role for extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319, 991–997 10.1124/jpet.106.107367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wei F., Yan J., and Tang D. (2011) Extracellular signal-regulated kinases modulate DNA damage response: a contributing factor to using MEK inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 5476–5482 10.2174/092986711798194388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kolb R. H., Greer P. M., Cao P. T., Cowan K. H., and Yan Y. (2012) ERK1/2 signaling plays an important role in topoisomerase II poison-induced G2/M checkpoint activation. PLoS ONE 7, e50281 10.1371/journal.pone.0050281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghayur T., Hugunin M., Talanian R. V., Ratnofsky S., Quinlan C., Emoto Y., Pandey P., Datta R., Huang Y., Kharbanda S., Allen H., Kamen R., Wong W., and Kufe D. (1996) Proteolytic activation of protein kinase Cδ by an ICE/CED 3-like protease induces characteristics of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 184, 2399–2404 10.1084/jem.184.6.2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wiggin G. R., Soloaga A., Foster J. M., Murray-Tait V., Cohen P., and Arthur J. S. (2002) MSK1 and MSK2 are required for the mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of CREB and ATF1 in fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2871–2881 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2871-2881.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi G. X., Cai W., and Andres D. A. (2012) Rit-mediated stress resistance involves a p38-mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1)-dependent cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) activation cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 39859–39868 10.1074/jbc.M112.384248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adewumi I., López C., and Davie J. R. (2019) Mitogen and stress- activated protein kinase regulated gene expression in cancer cells. Adv. Biol. Regul. 71, 147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dittmann K., Mayer C., Fehrenbacher B., Schaller M., Raju U., Milas L., Chen D. J., Kehlbach R., and Rodemann H. P. (2005) Radiation-induced epidermal growth factor receptor nuclear import is linked to activation of DNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31182–31189 10.1074/jbc.M506591200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodemann H. P., Dittmann K., and Toulany M. (2007) Radiation-induced EGFR-signaling and control of DNA-damage repair. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 83, 781–791 10.1080/09553000701769970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liccardi G., Hartley J. A., and Hochhauser D. (2011) EGFR nuclear translocation modulates DNA repair following cisplatin and ionizing radiation treatment. Cancer Res. 71, 1103–1114 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsu S. C., Miller S. A., Wang Y., and Hung M. C. (2009) Nuclear EGFR is required for cisplatin resistance and DNA repair. Am. J. Transl. Res. 1, 249–258 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chou R. H., Wang Y. N., Hsieh Y. H., Li L. Y., Xia W., Chang W. C., Chang L. C., Cheng C. C., Lai C. C., Hsu J. L., Chang W. J., Chiang S. Y., Lee H. J., Liao H. W., Chuang P. H., et al. (2014) EGFR modulates DNA synthesis and repair through Tyr phosphorylation of histone H4. Dev. Cell 30, 224–237 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reyskens K. M., and Arthur J. S. (2016) Emerging roles of the mitogen and stress activated kinases MSK1 and MSK2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sawicka A., Hartl D., Goiser M., Pusch O., Stocsits R. R., Tamir I. M., Mechtler K., and Seiser C. (2014) H3S28 phosphorylation is a hallmark of the transcriptional response to cellular stress. Genome Res. 24, 1808–1820 10.1101/gr.176255.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Drobic B., Pérez-Cadahia B., Yu J., Kung S. K., and Davie J. R. (2010) Promoter chromatin remodeling of immediate-early genes is mediated through H3 phosphorylation at either serine 28 or 10 by the MSK1 multi-protein complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3196–3208 10.1093/nar/gkq030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lang E., Bissinger R., Fajol A., Salker M. S., Singh Y., Zelenak C., Ghashghaeinia M., Gu S., Jilani K., Lupescu A., Reyskens K. M., Ackermann T. F., Föller M., Schleicher E., Sheffield W. P., et al. (2015) Accelerated apoptotic death and in vivo turnover of erythrocytes in mice lacking functional mitogen- and stress-activated kinase MSK1/2. Sci. Rep. 5, 17316 10.1038/srep17316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nyati M. K., Feng F. Y., Maheshwari D., Varambally S., Zielske S. P., Ahsan A., Chun P. Y., Arora V. A., Davis M. A., Jung M., Ljungman M., Canman C. E., Chinnaiyan A. M., and Lawrence T. S. (2006) Ataxia telangiectasia mutated down-regulates phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 via activation of MKP-1 in response to radiation. Cancer Res. 66, 11554–11559 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kucharska A., Rushworth L. K., Staples C., Morrice N. A., and Keyse S. M. (2009) Regulation of the inducible nuclear dual-specificity phosphatase DUSP5 by ERK MAPK. Cell. Signal. 21, 1794–1805 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bagnyukova T. V., Restifo D., Beeharry N., Gabitova L., Li T., Serebriiskii I. G., Golemis E. A., and Astsaturov I. (2013) DUSP6 regulates drug sensitivity by modulating DNA damage response. Br. J. Cancer 109, 1063–1071 10.1038/bjc.2013.353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Quissell D. O., Barzen K. A., Redman R. S., Camden J. M., and Turner J. T. (1998) Development and characterization of SV40 immortalized rat parotid acinar cell lines. In Vitro Cellular Dev. Biol. Anim. 34, 58–67 10.1007/s11626-998-0054-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miyamoto A., Nakayama K., Imaki H., Hirose S., Jiang Y., Abe M., Tsukiyama T., Nagahama H., Ohno S., Hatakeyama S., and Nakayama K. I. (2002) Increased proliferation of B cells and auto-immunity in mice lacking protein kinase Cδ. Nature 416, 865–869 10.1038/416865a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.